Abstract

The genetic heterogeneity of Heyndrickxia sporothermodurans (formerly Bacillus sporothermodurans) was evaluated using whole genome sequencing. The genomes of 29 previously identified Heyndrickxia sporothermodurans and two Heyndrickxia vini strains isolated from ultra-high-temperature (UHT)-treated milk were sequenced by short-read (Illumina) sequencing. After sequence analysis, the two H. vini strains could be reclassified as H. sporothermodurans. In addition, the genomes of the H. sporothermodurans type strain (DSM 10599T) and the closest phylogenetic neighbors Heyndrickxia oleronia (DSM 9356T) and Heyndrickxia vini (JCM 19841T) were also sequenced using both long (MinION) and short-read (Illumina) sequencing. By hybrid sequence assembly, the genome of the H. sporothermodurans type strain was enlarged by 15% relative to the short-read assembly. This noticeable increase was probably due to numerous mobile elements in the genome that are presumptively related to spore heat tolerance. Phylogenetic studies based on 16S rDNA gene sequence, core genome, single-nucleotide polymorphisms and ANI/dDDH, showed that H. vini is highly related to H. sporothermodurans. When examining the genome sequences of all H. sporothermodurans strains from this study, together with 4 H. sporothermodurans genomes available in the GenBank database, the majority of the 36 strains examined occurred in a clonal lineage with less than 100 SNPs. These data substantiate previous reports on the existence and spread of a genetically highly homogenous and heat resistant spore clone, i.e., the HRS-clone.

Keywords: Bacillus, sporothermodurans, oleronia, vini, phylogeny, spores, UHT-milk, diversity, core genome, Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs), Heyndrickxia

1. Introduction

Heyndrickxia (H.) sporothermodurans, H. oleronia and H. vini are gram-positive, rod-shaped and endospore-forming bacteria [1,2,3]. These three species are closely related, with their nearest phylogenetic neighbors being Margalitia shackletonii and Bacillus (B.) acidicola [4]. Recently a new classification of Bacillus species was published by Gupta et al. (2020), which proposes a reclassification and renaming of, among others, B. sporothermodurans [5]. Based on this valid taxonomic reclassification, the new names listed in Table 1 were used in this study.

Table 1.

Previous (basonym) and new combinations (comb. nov.) of Bacillus species used in this study based on their reclassification as described by Gupta et al. (2020) [5,6].

| Previous Combination (Basonym) | Publication | New Combination (comb. nov.) | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus sporothermodurans | Pettersson et al., 1996 | Heyndrickxia sporothermodurans | Gupta et al., 2020 |

| Bacillus vini | Ma et al., 2017 | Heyndrickxia vini | Gupta et al., 2020 |

| Bacillus oleronius | Kuhnigk et al., 1996 | Heyndrickxia oleronia | Gupta et al., 2020 |

| Bacillus shackletonii | Logan et al., 2004 | Margalitia shackletonii | Gupta et al., 2020 |

| Bacillus camelliae | Niu et al., 2018 | Margalitia camelliae | Gupta et al., 2020 |

| Bacillus ginsengihumi | Ten et al., 2007 | Weizmannia ginsengihumi | Gupta et al., 2020 |

| Bacillus fordii | Scheldeman et al., 2004 | Siminovitchia fordii | Gupta et al., 2020 |

| Bacillus firmus | Bredemann and Werner 1933 | Cytobacillus firmus | Patel and Gupta 2020 |

| Bacillus luciferensis | Logan et al., 2002 | Gottfriedia luciferensis | Gupta et al., 2020 |

Heyndrickxia sporothermodurans is a non-pathogenic bacterium whose highly-heat-resistant spores (HRS) are able to survive the food sterilization process [7]. Their presence in milk products does not lead to visible spoilage, but it leads to breaching of commercial sterility. Since the first report of Heyndrickxia contamination of ultra-high-temperature (UHT)- and sterilized milk in Italy, Austria and Germany [8] and the description of the new species H. sporothermodurans (Bacillus sporothermodurans sp. nov.) [1], many countries reported the isolation of H. sporothermodurans from UHT milk, feed and food [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Various authors discussed the heterogeneity of H. sporothermodurans strains and the potential spread of a specific clonal linage, the so-called HRS-clone [17,18]. However, methods like ribotyping and fingerprinting methods show a higher genetic diversity than previously assumed [4,14].

Heyndrickxia oleronia was described in 1995 by Kuhnigk et al. [2]. It was first isolated from the termite Reticulitermes santonensis (Feytaud) [2], but later also from raw milk and feed [4,9,13,19]. Heyndrickxia oleronia is phylogenetically closely related to H. sporothermodurans and was found to be difficult to distinguish from the latter on the basis of biochemical and physiological characteristics solely [4]. The draft genome of H. oleronia was published 2017 by Owuso-Darko et al. [20] with more than 500 contigs after sequence assembly. This underlines the difficulty of assembling Heyndrickxia species genomes using a sequencing technique such as Illumina MiSeq sequencing that generates short-reads only. Heyndrickxia vini was isolated from an alcohol fermentation pit mud and was described in 2016 by Ma et al. [3]. This Heyndrickxia sp. showed the closest relatedness to H. sporothermodurans and H. oleronia type strains, with 98.4% and 97.2% sequence similarity of the 16S rRNA gene. Classical DNA-DNA hybridization values were 33.3% and 42.8% between H. vini vs. H. sporothermodurans and H. vini vs. H. oleronia [3], respectively, indicating that these are different species. Based on further differences in the morphological, physiological, and biochemical characteristics, when compared to both H. sporothermodurans and H. oleronia, the strain was then described as a new species, namely H. vini [3], despite the lack of whole genome sequencing data.

Whole genome sequencing offers valuable support in understanding the genetic background and phylogenetic diversity of bacteria. It currently provides the best possibility to clarify genomic relationships with the highest discriminatory power [21]. At the time of writing, the genome of the H. vini type strain was not published and the genome sequences of only five H. sporothermodurans strains were available, i.e., those of the type strain DSM 10599T, strain BR3 (also named BR12), strain SAD, strain SA01 and B4102 [15,22]. Their assemblies consist of 100–800 contigs, which is a relatively high number when compared to other bacterial species. Usually, depending on the species, contig numbers between 15 and 200 contigs are produced by short-read sequence assembling. For example, published contig numbers are 15 to 30 contigs for Campylobacter jejuni [23], 50 to 100 for Salmonella enterica [23], 10 to 30 for Listeria monocytogenes [23,24], 80 to 100 for Escherichia coli [24,25] and 50 to 100 contigs for genomes of the B. cereus group [26]. The aim of this study was to increase the availability of H. sporothermodurans genomic DNA sequences by sequencing an additional 29 strain genomes of H. sporothermodurans. These isolates represent problematic spoilage bacteria in the food sector and were isolated from UHT milk. In addition, the combination of short- and long-read sequencing should significantly improve the genome quality of the type strains of H. sporothermodurans, H. oleronia and H. vini. Based on the genomic sequences, this study furthermore aimed to evaluate the genetic diversity of the H. sporothermodurans group, consisting of the closely related species of H. sporothermodurans, H. oleronia and H. vini, and to determine phylogenetic relationships between H. sporothermodurans strains.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Media

Thirty H. sporothermodurans strains (29 isolates and the type strain DSM 10599T), three H. vini strains (two presumptively identified isolates and the type strain JCM 19841T) and the H. oleronia type strain DSM 9356T (Table 2) were obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany) or were kindly provided by the ZIEL—Institute for Food & Health (TU Munich, Germany) and by Tetra Holdings GmbH (Aseptic and Filling Solutions, Stuttgart, Germany). The H. vini strains M5352-102 and M5572-6 were previously identified on the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequencing in the absence of whole genome sequencing data. All strains were cultivated aerobically in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) supplemented with 1 mg/L vitamin B12 (B12) (VWR, Darmstadt, Germany) or on BHI agar (Carl Roth) + 1 mg/L B12 at 37 °C for 48 h. Default parameters were used for all protocols and software unless otherwise specified. Genomic DNA was extracted from 4 mL of culture (48 h) using the ZR fungal/bacterial DNA miniprep kit (Zymo Research, Freiburg, Germany) Illumina sequencing and the Genomic Micro AX Bacteria+ kit (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland) for Oxford Nanopore sequencing. DNA quality assurance and quantitation were performed using the Qubit fluorometer and dsDNA BR Assay kit (Life Technologies, US). Additional sequence data used in this study was shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Strains used in this study. * DSMZ = German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures; TU Munich = Technical University of Munich; JCM Riken BRC = Japan Collection of Microorganisms.

| Species | Strain | Isolation Country | Isolation Source | Isolation Date (and Dairy) | Provided by * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. sporothermodurans | DSM 10599T | Italy | UHT milk | 1993 | DSMZ |

| M3420-12 | Iran | UHT milk | 2011 | Tetra Holdings GmbH | |

| M5055-A | Ecuador | UHT milk | 2017 | Tetra Holdings GmbH | |

| M5233-6 | Albania | UHT milk | 2018 | Tetra Holdings GmbH | |

| M5311-1 | South Africa | UHT milk | 2018 | Tetra Holdings GmbH | |

| M5311-2 | South Africa | UHT milk | 2018 | Tetra Holdings GmbH | |

| M5523-4 | Czech Republic | UHT milk | 2019 | Tetra Holdings GmbH | |

| M5530-17 | Czech Republic | UHT milk | 2019 | Tetra Holdings GmbH | |

| M5547-20 | Italy | UHT milk | 2019 | Tetra Holdings GmbH | |

| M5547-25 | Italy | UHT milk | 2019 | Tetra Holdings GmbH | |

| L1_140 | Germany | UHT milk | 07 July 1999 A | TU Munich | |

| L1_141 | Germany | UHT milk | 23 June 1999 B | TU Munich | |

| L1_142 | Germany | UHT milk | 29 July 2002 B | TU Munich | |

| L1_143 | Germany | UHT milk | 18 June 2003 B | TU Munich | |

| L1_144 | Germany | UHT milk | 19 August 2003 B | TU Munich | |

| L1_145 | Germany | UHT milk | 26 August 2003 B | TU Munich | |

| L1_146 | Germany | UHT milk | 02 December 2003 B | TU Munich | |

| L1_149 | Germany | UHT milk | 22 June 2004 C | TU Munich | |

| L1_150 | Germany | UHT milk | 15 October 2004 C | TU Munich | |

| L1_151 | Germany | UHT milk | 23 August 2006 D | TU Munich | |

| L1_152 | Germany | UHT milk | 19 July 2007 D | TU Munich | |

| L1_153 | Germany | UHT milk | 19 July 2007 D | TU Munich | |

| L1_154 | Germany | UHT milk | 17 July 2007 D | TU Munich | |

| L1_155 | Germany | UHT milk | 31 July 2007 D | TU Munich | |

| L1_156 | Germany | UHT milk | 20 January 2010 D | TU Munich | |

| L1_157 | Germany | UHT milk | 20 January 2010 D | TU Munich | |

| L1_158 | Germany | UHT milk | 26 September 2014 E | TU Munich | |

| L1_159 | Germany | UHT milk | 26 September 2014 E | TU Munich | |

| L1_160 | Germany | UHT milk | 26 September 2014 E | TU Munich | |

| L1_161 | Germany | UHT milk | 26 September 2014 E | TU Munich | |

| H. vini (based on 16S rRNA) | M5352-102 | Italy | UHT milk | 2018 | Tetra Holdings GmbH |

| M5572-6 | Jordan | UHT milk (banana) | 2019 | Tetra Holdings GmbH | |

| H. vini | LAM0415T/JCM 19841T | China | alcohol fermentation pit mud | before 2016 | JCM Riken BRC |

| H. oleronia | DSM 9356T | France | termite | 1996 | DSMZ |

Table 3.

Additional sequence data used in this study.

| Species | Strain | Isolation Country and Year | Isolation Source | GenBank | SRA | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. sporothermo- durans | BR3 (BR12) | Brazil, 2012 | UHT milk | NAZC01000000 | SRR8741693 | [22] |

| SAD | South Africa, 2015 | UHT milk | NAZB01000000 | SRR8732968 | [22] | |

| SA01 | South Africa, 2015 | UHT milk | NAZA01000000 | SRR8732969 | [22] | |

| B4102 | The Netherlands, 2012 | Indian curry | LQYN00000000 | N/A | [15] |

2.2. Genome Sequencing, Assembly and Annotation

2.2.1. Illumina MiSeq Short-Read Sequencing and Assembly

The sequencing library was prepared with an Illumina TruSeq nano DNA LT library prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA) and sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq sequencer using the Illumina MiSeq V3 reagent kit according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The fastq files were quality controlled by FastQC 0.11.7 and assembled using SPADes Version 3.10.0 on the PATRIC BRC website (https://patricbrc.org/) [27]. The assemblies were imported into the commercial Geneious software (version 9.1.8) for sequence analysis (https://www.geneious.com). Contigs of less than 300 bp or with coverage <20× were removed manually and the remaining assemblies were exported as fasta files. Possible contamination of the assemblies was screened using the ContEst16S tool [28]. The genome quality was assessed with the PATRIC quality tool [27].

2.2.2. MinION Nanopore Long Read Sequencing and Assembly

Long sequence reads were obtained by library preparation with the MinION 1D Native DNA barcoding genomic DNA protocol (with the Oxford Nanopore Ligation Sequencing Kit (EXP-NBD104) and the Oxford Nanopore Native Barcoding Expansion Kit (SQK-LSK 109)) and by sequencing using an Oxford Nanopore MinION MK1B sequencer with a MinION Flow Cell (R9.4.1) and a Flow Cell Priming Kit (EXP-FLP002). The long sequence reads of the H. sporothermodurans type strain DSM 10599T were obtained using the same protocol, but with the following modifications, that were required due to unusual clumping of the magnetic beads during purification. For DNA clean-up of this strain, it was necessary to dilute the samples by 1:5 before adding the magnetic beads and to elute the DNA at 70 °C. Furthermore, this library was sequenced on a MinION MK1B sequencer but with a Flongle Flow Cell (FLO-FLG001). Reads were extracted from FAST5 files using the Guppy pipeline v. 2.3.1. (https://nanoporetech.com), demultiplexed by Porechop [21] and filtered by Nonofilt (v. 2.6.0) [29]. The reads were trimmed by the FastQC Utilities at PATRIC [30]. Trimmed MinION reads were hybrid assembled together with corresponding Illumina short-reads on the PATRIC website https://www.patricbrc.org/ [30] with Unicycler (no trim, 4 racon iterations, 0 pilon iterations, 300 bp minimum contig length and 30× min contig coverage). The assemblies were imported into Geneious® and if more than 1 contig was generated by Unicycler, the smaller contigs were mapped against the largest contig and well-mapping (redundant) sequences were removed from the assembly. Additionally, the ends of the largest contigs were checked for overlap and circularized if they matched. Circular chromosomes were rotated to dnak as starting point. Possible contamination of the assemblies was screened using the ContEst16S tool [22]. The genome quality was assessed with the PATRIC quality tool [21].

2.2.3. Annotation, Molecular Analysis and Core Gene Detection

All assembled contigs were annotated using the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline version 4.10 [31,32] with default parameters. All annotated genomes are available with DDBJ/ENA/GenBank, the accession number given in Table 4. Molecular and general analysis of assemblies, annotations, coverage and genetic structure were investigated using Geneious® 9.1.8. For generating the genome’s core and accessory genes, the assembled contigs were annotated with Prokka V1.14.5 [33] and the resulting gff3 files were processed with the pangenome pipeline Roary V3.11 [34]. Prokka and Roary were carried out with default settings at the Galaxy Europe V1.3 cloud (https://usegalaxy.eu/) [35]. Due to illogical results (see results), different settings of the pipeline were checked (minimum percentage identity for blastp, percentage of isolates a gene must be in to be core, splitting paralogs, maximum number of cluster) to find the cause for the observed phenomenon. For comparison, we increased the Protein Identity interval for blastp to 99% (95% default).

Table 4.

Characteristics of the sequenced genomes (BioProject PRJNA639094).

| Strain | DDBJ/ENA/ GenBank Accession Number |

Number of Raw Reads | Coverage | Genome Size | Mol GC% | Contigs | N50 | Genes (Total) | tRNA | rRNA | SRA Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heyndrickxia sporothermodurans ( basonym: Bacillus sporothermodurans) | |||||||||||

| DSM 10599T short-reads | JAEKDY000000000 | 1,662,070 | 104.64× | 3,839,826 | 35.75 | 302 | 27,181 | 4032 | 96 | 33 | SRR13249535 |

| DSM 10599T Hybrid assembly | CP066701 | 1,662,070 (Illumina) 232,544 (Nanopore) |

191.36× | 4,417,946 | 36.34 | 1 | 1 contig | 4554 | 99 | 30 | SRR13249535 (Illumina) SRR13347551 (Nanopore) |

| M3420-12 | JABWUU000000000 | 1,214,420 | 82.24× | 3,580,829 | 35.93 | 291 | 25,466 | 3713 | 77 | 29 | SRR13249560 |

| M5055-A | JABWUT000000000 | 1,160,538 | 77.17× | 3,662,309 | 36.01 | 348 | 20,956 | 3890 | 97 | 35 | SRR13249559 |

| M5233-6 | JABWUS000000000 | 1,167,612 | 76.00× | 3,746,330 | 35.91 | 363 | 20,329 | 3910 | 79 | 30 | SRR13249548 |

| M5311-1 | JABWUR000000000 | 1,211,006 | 81.10× | 3,615,469 | 35.85 | 346 | 20,889 | 3819 | 78 | 32 | SRR13249537 |

| M5311-2 | JABWUQ000000000 | 1,205,508 | 82.18× | 3,550,370 | 35.83 | 333 | 20,966 | 3703 | 95 | 33 | SRR13249530 |

| M5523-4 | JABWUP000000000 | 1,192,692 | 81.50× | 3,569,406 | 35.95 | 341 | 20,150 | 3719 | 81 | 31 | SRR13249529 |

| M5530-17 | JABWUO000000000 | 1,196,538 | 81.52× | 3,576,306 | 35.94 | 338 | 20,329 | 3715 | 78 | 31 | SRR13249528 |

| M5547-20 | JABWUN000000000 | 1,258,834 | 81.58× | 3,764,103 | 35.93 | 372 | 20,038 | 4025 | 97 | 33 | SRR13249527 |

| M5547-25 | JABWUM000000000 | 1,551,052 | 106.16× | 3,534,820 | 35.91 | 342 | 20,854 | 3699 | 79 | 32 | SRR13249526 |

| M5352-102 * | JABWTR000000000 | 1,673,766 | 120.90× | 3,376,234 | 35.88 | 332 | 20,219 | 3551 | 79 | 30 | SRR13249538 |

| M5572-6 * | JABWTQ000000000 | 1,661,774 | 111.93× | 3,612,108 | 35.97 | 321 | 22,597 | 3780 | 97 | 33 | SRR13249536 |

| L1_140 | JABWUJ000000000 | 1,300,432 | 82.43× | 3,817,614 | 35.79 | 310 | 30,062 | 4026 | 96 | 33 | SRR13249525 |

| L1_141 | JABWUI000000000 | 1,281,714 | 84.40× | 3,684,244 | 35.79 | 319 | 24,263 | 3863 | 95 | 33 | SRR13249558 |

| L1_142 | JABWUH000000000 | 1,265,780 | 82.99× | 3,677,671 | 35.75 | 326 | 28,594 | 3886 | 79 | 32 | SRR13249557 |

| L1_143 | JABWUG000000000 | 1,361,164 | 89.88× | 3,676,925 | 35.84 | 315 | 25,507 | 3896 | 95 | 34 | SRR13249556 |

| L1_144 | JABWUF000000000 | 1,446,376 | 90.58× | 3,857,917 | 35.81 | 339 | 25,432 | 4115 | 96 | 35 | SRR13249555 |

| L1_145 | JABWUE000000000 | 1,142,112 | 72.70× | 3,811,445 | 35.83 | 326 | 25,433 | 4014 | 96 | 33 | SRR13249554 |

| L1_146 | JABWUD000000000 | 1,476,620 | 93.85× | 3,826,729 | 35.82 | 351 | 24,470 | 4042 | 96 | 33 | SRR13249553 |

| L1_149 | JABWUC000000000 | 1,468,760 | 92.28× | 3,886,000 | 35.84 | 336 | 23,762 | 4069 | 95 | 34 | SRR13249552 |

| L1_150 | JABWUB000000000 | 1,232,426 | 80.78× | 3,698,569 | 35.86 | 317 | 25,508 | 3850 | 95 | 34 | SRR13249551 |

| L1_151 | JABWUA000000000 | 1,390,644 | 93.45× | 3,628,299 | 35.85 | 320 | 26,528 | 3783 | 78 | 30 | SRR13249550 |

| L1_152 | JABWTZ000000000 | 1,306,056 | 87.84× | 3,605,120 | 35.87 | 313 | 26,883 | 3748 | 78 | 32 | SRR13249549 |

| L1_153 | JABWTY000000000 | 1,389,634 | 95.93× | 3,512,664 | 35.86 | 309 | 26,406 | 3694 | 78 | 32 | SRR13249547 |

| L1_154 | JABWTX000000000 | 1,185,268 | 84.22× | 3,418,001 | 35.85 | 301 | 26,933 | 3548 | 77 | 32 | SRR13249546 |

| L1_155 | JABWTW000000000 | 1,832,218 | 121.31× | 3,676,944 | 35.87 | 324 | 25,595 | 3843 | 96 | 33 | SRR13249545 |

| L1_156 | JABWUL000000000 | 1,940,212 | 121.72× | 3,877,835 | 35.90 | 342 | 24,263 | 4023 | 97 | 33 | SRR13249544 |

| L1_157 | JABWUK000000000 | 1,770,320 | 119.84× | 3,613,127 | 35.88 | 312 | 25,846 | 3751 | 78 | 31 | SRR13249543 |

| L1_158 | JABWTV000000000 | 1,761,290 | 121.53× | 3,535,146 | 35.84 | 323 | 23,762 | 3687 | 77 | 32 | SRR13249542 |

| L1_159 | JABWTU000000000 | 1,724,638 | 124.93× | 3,372,204 | 35.89 | 304 | 23,967 | 3484 | 77 | 32 | SRR13249541 |

| L1_160 | JABWTT000000000 | 1,164,458 | 78.10× | 3,633,431 | 35.86 | 334 | 24,295 | 3754 | 80 | 34 | SRR13249540 |

| L1_161 | JABWTS000000000 | 1,814,922 | 120.51× | 3,680,123 | 35.89 | 342 | 22,342 | 3785 | 78 | 31 | SRR13249539 |

| * formerly H. vini (based on 16S) | |||||||||||

| Heyndrickxia vini ( basonym: Bacillus vini) | |||||||||||

| LAM0415T/ JCM 19841T Hybrid assembly |

CP065425 | 2,323,916 (Illumina) 145,000 (Nanopore) |

379× | 4,309,805 | 35.97 | 1 | circular | 4263 | 97 | 30 | SRR13249532 (Illumina) SRR13249531 (Nanopore) |

| Heyndrickxia oleronia ( basonym: Bacillus oleronius) | |||||||||||

| DSM 9356T Hybrid assembly | CP065424 | 1,700,898 (Illumina) 109,411 (Nanopore) |

282× | 5,198,760 | 35.13 | 1 | circular | 5186 | 145 | 36 | SRR13249534 (Illumina) SRR13249533 (Nanopore) |

2.3. Overall Genome Related-Indexes and Phylogenomics-Based Subtyping

2.3.1. 16S rRNA Gene Phylogeny

Pairwise sequence similarities were calculated using the 16S rRNA gene sequences available via the GGDC web server [36] at http://ggdc.dsmz.de/. Phylogenies were inferred by the TYGS web server [37]. The following steps were done by this service: The extraction of the 16S rDNA gene sequence from whole genome data, determination of the closest type strains by blast+ comparison and a multiple sequence alignment was created with MUSCLE [38]. Maximum likelihood (ML) and maximum parsimony (MP) trees were reconstructed from the alignments with RAxML [39] and TNT [40], respectively. For ML, rapid bootstrapping in conjunction with the autoMRE bootstopping criterion [41] and subsequent search for the best tree was used; for MP, 1000 bootstrapping replicates were used in conjunction with tree-bisection-and-reconnection branch swapping and ten random sequence addition replicates.

2.3.2. Core Gene-Based Codon Tree

For further phylogenetic investigations a codon tree based on up to 1000 core genes was generated with PATRIC BRC [30]. The default was set for Codon Trees, which utilizes the amino acid and nucleotide sequences from up to 1000 PATRIC’s global Protein Families (PGFams). These are picked randomly to build an alignment and then generate a tree based on the differences within those selected sequences. Both the protein (amino acid) and gene (nucleotide) sequences are used for each of the selected genes from the PGFams. Protein sequences are aligned using MUSCLE [38], and the nucleotide coding gene sequences are aligned using the codon align function of BioPython [42]. A concatenated alignment of all proteins and nucleotides was converted to a phylip formatted file. Then a partitions file for RaxML [39] was generated, describing the alignment in terms of the proteins and then the first, second and third codon positions. Support values were generated using 100 rounds of the “Rapid” bootstrapping option of RaxML.

2.3.3. Cohesive Genomic Sequence Comparisons (ANI, dDDH)

The overall genome-related indexes, i.e., average nucleotide identity (ANI) and digital DNA-DNA hybridization were used to compare the H. sporothermodurans group species. The Blast+ (ANIb) from all pairwise genome comparisons were computed at the online service JSpeciesWS [43]. Digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH) values were estimated at GGDC (Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator) using GGDC 2.1 with BLAST+ alignment and recommended formula 2 [36]. The proposed and generally accepted species boundary for ANI and dDDH values are 95–96% and 70%, respectively [44].

2.3.4. Identifying Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs)

The online service CSI Phylogeny-based subtyping (SNP CSI Phylogeny 1.4) calls SNPs and was performed using whole genome sequence data (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/CSIPhylogeny/) [45]. The hybrid sequence assembly from H. sporothermodurans DSM 10599T was used as reference genome and the raw reads (Illumina short-read sequence) were uploaded for each strain. Due to the unavailability of Sequence Read Archive (SRA) data (raw reads) for strain B4102 in the databases, the assembled data stored in the GenBank database were used. The analysis was submitted with the following parameters: a minimal depth at SNP positions of 25 reads, a minimal relative depth at SNP positions of 10%, a minimal distance between SNPs of 10 bp, a minimal Z-score of 1.96, a minimal SNP quality of 30, a minimal read mapping quality of 25 and ignore heterozygous SNPs activated. The pipeline and the parameters were described by Kaas et al. [45] and evaluated by Saltykova et al. [46]. Briefly, the pipeline performs the following steps: reads are mapped to the reference genome and SNPs are called. The SNPs are then filtered according to the submitted parameters in order to obtain a higher quality and positions that fail validation in at least one of the mapping steps are excluded from the SNP matrix.

3. Results

3.1. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

In this study, we sequenced 29 H. sporothermodurans and two presumptive H. vini strains by short-read sequencing. The two presumptive H. vini strains (identification of the strains was based on previous 16S rRNA gene Sanger sequencing) could be reclassified as H. sporothermodurans (see below). Additionally, we sequenced the type strains H. sporothermodurans DSM 10599T, H. vini JCM 19841T and H. oleronia DSM 9356T using a combination of short- and long-read sequencing technologies. Sequencing and analysis was performed according to the methodology proposed by Chun et al. [44]. The quality of the raw reads was checked with FastQC, genome assembly quality was assessed with PATRIC BRC and contaminations were excluded by using the ContEst16S software. A summary of the sequenced genome characteristics is shown in Table 4. The data have been deposited to BioProject accession number PRJNA639094 in the NCBI BioProject database.

For the short-read-sequenced H. sporothermodurans genomes, sizes ranged from 3,372,204 bp to 3,886,000 bp with a GC content of 35.75 to 36.01 mol%. The number of gene coding sequences (CDS) ranged from 3758 to 4115. The type strain H. sporothermodurans DSM 10599T assembly yielded 302 contigs after Illumina short-read sequencing, but could be improved to 1 contig by performing a hybrid assembly of Illumina short-read and MinION long read sequences. Using this method, the H. oleronia strain DSM 9356T could be assembled into a single closed chromosome sequence, opposed to the short-read approach, which resulted in >500 contigs. When compared to the short-read assembly, the hybrid assembly noticeably increased the genome size from 3,839,826 bp to 4,417,946 bp (15.1%) for H. sporothermodurans DSM 10599T and from 5,083,966 bp to 5,198,760 bp (2.3%) for H. oleronia DSM 9356T. Similarly, the GC content increased from 35.75 to 36.34 mol% GC for H. sporothermodurans DSM 10599T and from 34.97 to 35.13 mol% GC for H. oleronia DSM 9356T. While the number of genes increased from 4032 to 4554 CDS for H. sporothermodurans DSM 10599T, a decrease from 5530 to 5397 CDS was observed for H. oleronia DSM 9356T. The massive increase in genome length, GC content and the number of genes in the hybrid assembly approach of H. sporothermodurans DSM 10599T could be explained by an elevated detection of repetitive sequences like transposons, integrases and other mobile genetic elements, which varied between 1700 and 4000 nucleotides in size. In the short-read assembly (302 contigs) of H. sporothermodurans DSM 10599T there were often residues of repeat regions located at the contig ends. In the corresponding hybrid assembly, these repeat regions were distributed over the whole genome sequence and are identified with a number of 340 regions (by Geneious®). This number of repeat regions is similar to the contig number in the short-read assembly. This finding suggests a correlation between the number of contigs in short-read assembly and the number of repetitive regions in the respective genome. In the short-read assembly, there are several potential matching short-reads at the regions of repetitive sequences (>500 bp), where the assembly has to be terminated and the end of a contig arises. With hybrid assembly (using long-reads of several kilobases in length), these repetitive regions could be continuous sequenced and assigned. This allowed the contigs to be placed in the correct order and additional genes were therefore found within the repetitive regions.

In addition, this study presents the first whole genome sequence of H. vini JCM 19841T. The sequence length, mol% GC content and gene number determined by the hybrid assembly for the H. vini JCM 19841T genome were 4,309,805 bp, 35.97 mol% GC and 4373 CDS, respectively (Table 4).

Analysis of protein-encoding genes revealed that the genomes of the three characterized Heyndrickxia species (H. sporothermodurans, H. oleronia and H. vini) share 164 core genes (Supplementary Table S1). Surprisingly, H. sporothermodurans and H. vini share 965 core genes, while only 156 core genes were detected for H. sporothermodurans and H. oleronia. The latter number lies below the amount of core genes determined for all three species (n = 164) and thus suggests a suboptimal analysis (Roary pipeline) of the sequencing data as the numbers of core genes are expected to increase with a decreasing number of species examined. In order to reveal the underlying cause, the effects of slight changes to the parameters of the analysis pipeline were examined: When the protein identity interval was increased (sets the minimum percentage identity for protein match) to 99% (default was 95%), expectedly, less core genes were found, but the ratio of core genes between two species (44 genes) and all three species (42 genes) hinted towards an overall more reliable result (Supplementary Table S1). The observed anomaly (158 core genes for H. sporothermodurans + H. oleronia and 164 for H. sporothermodurans + H. oleronia + H. vini) was thus identified as a technical artifact in the blastp calculation (Roary pipeline). While the artifact had no significant influence on other results, it highlights the necessity of thorough manual examination of complex computational analyses.

Within the H. sporothermodurans species (n = 36 genome sequences) 1837 core genes (100% of strains harbor these genes), 490 soft core genes (95–99% of strains), 1923 shell genes (15–95% of strains), 2797 cloud genes (1–15% of strains) and 7047 different genes could be identified in total (1–100% of strains). Removing the more distant H. sporothermodurans strains SAD and B4102 (see below), the number of core genes within H. sporothermodurans genomes increased to 2187 (5649 different genes in total).

3.2. Heyndrickxia Sporothermodurans Interspecies Analysis

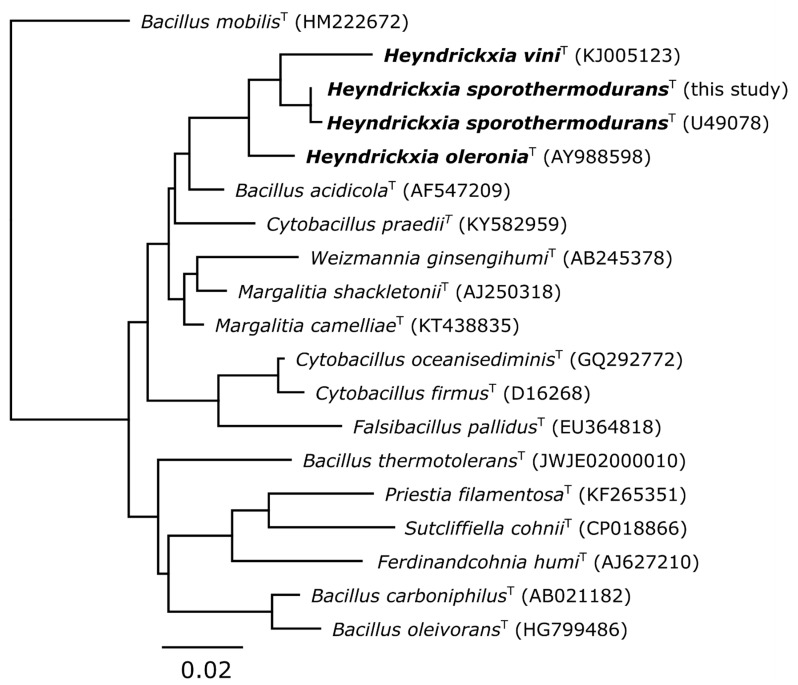

Phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences of type strains of the Heyndrickxia sporothermodurans related species was done by the TYGS platform [37] and is shown in Figure 1. In the phylogenetic reconstruction H. sporothermodurans, H. vini and H. oleronia are related and cluster closely in a monophyletic group, which we termed the H. sporothermodurans group and in which H. sporothermodurans shows a closer relationship with H. vini than with H. oleronia.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic 16S rDNA tree. The nearest type strains were selected, based on a blast+ 16S rDNA comparison. The phylogenic Maximum Likelihood (ML) tree inferred under the GTR + GAMMA model and rooted to Bacillus mobilis. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site.

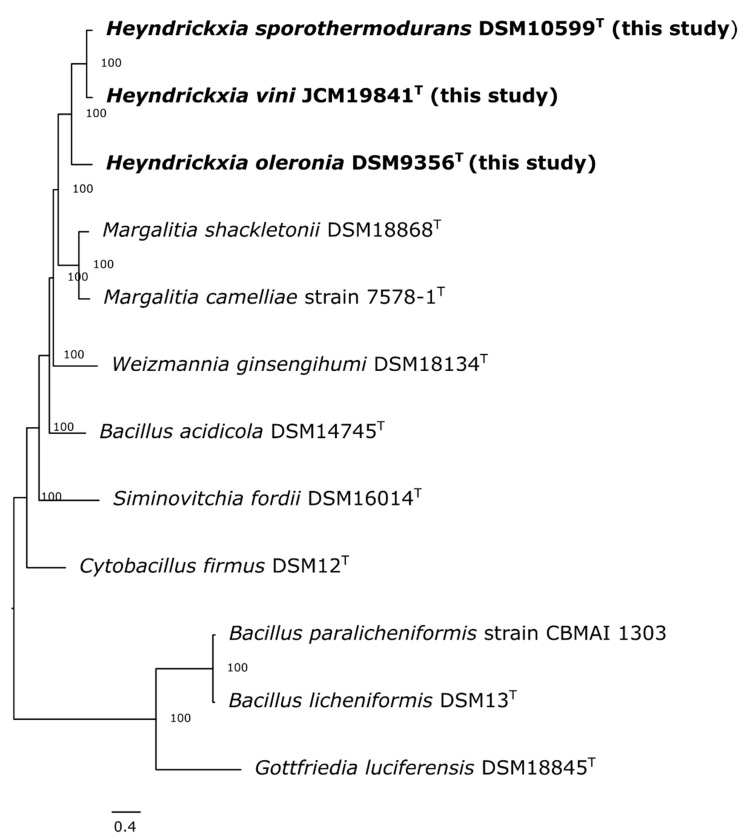

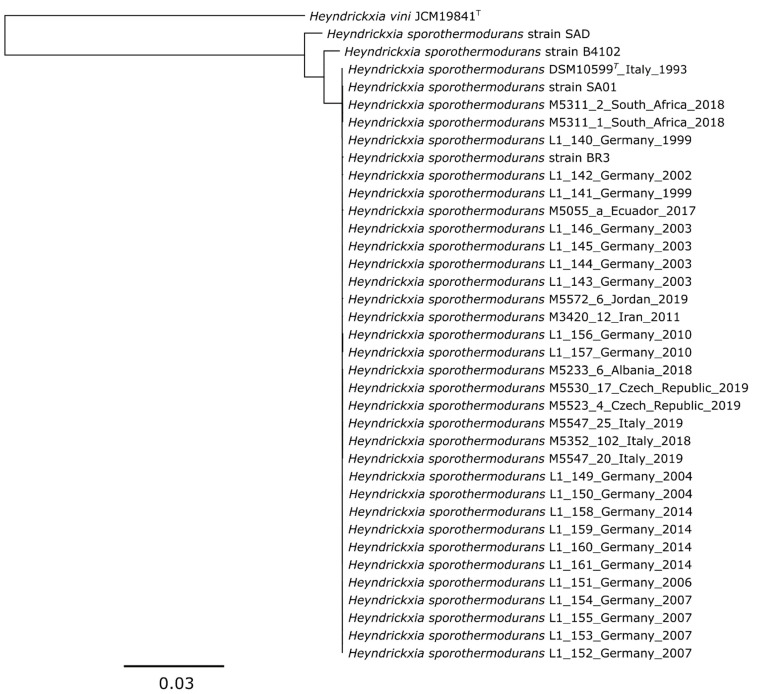

Using the complete genome sequences from hybrid assemblies of the type strains of H. sporothermodurans, H. vini and H. oleronia, a phylogenomic tree based on core genes was constructed. In this phylogenomic analysis the H. sporothermodurans and H. vini type strains clustered well apart from the H. oleronia type strain (Figure 2), confirming that H. sporothermodurans is more closely related to H. vini than to H. oleronia. Based on a core genes analysis performed with 595 genes, Margalitia (M.) shackletonii and M. camelliae form a monophyletic clade. Phylogenetically more distant to H. sporothermodurans, and without distinct clades, are W. ginsengihumi, B. acidicola, S. fordii and C. firmus. In addition, H. vini formed a clearly separated branch in the more detailed maximum-likelihood phylogenomic tree (Figure 3) confirming previous conventional DNA-DNA hybridization results that H. vini is distinguishable from H. sporothermodurans at the species level. The phylogenomic tree furthermore shows that the strains M5572-6 isolated in Jordan and M5352-102 from Italy, that were previously identified as H. vini on the basis of 16S rRNA sequence analyses (sanger sequencing), clustered closely together with other H. sporothermodurans strains in the phylogenomic analysis, indicating that these strains were previously identified incorrectly and were in fact also H. sporothermodurans strains (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree analysis (Codon Tree method selects 595 single-copy genes (PATRIC PGFams) and analyzes aligned proteins and coding DNA using the program RAxML version 8.2.11). Species were selected based on 16S rDNA analysis (Figure 1) and literature reference [2,3,4]. B. licheniformes, B. paralicheniformes and Gottfriedia luciferensis were selected as outgroup. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site.

Figure 3.

Phylogenomic tree analysis of H. vini and H. sporothermodurans strains (Codon Tree method which selects 1000 single-copy genes (PATRIC PGFams) and analyzes aligned proteins and coding DNA using the program RAxML version 8.2.11). The strains were named with the strain number, the country of origin and the year of isolation. Already published strains are DSM 10599T, SAD, B4102, SA01 and BR3 (see material section). The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site.

3.3. Heyndrickxia Sporothermodurans Intraspecies Analysis

In order to increase the resolution of the relationships of H. sporothermodurans strains, in a first step H. vini and then H. sporothermodurans strains showing less close relationship (SAD and B4102, see Figure 3) were omitted from the phylogenomic analyses. A core gene based phylogenomic tree for all available H. sporothermodurans strains, without H. vini type strain, is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. A SNP analysis was also carried out (Supplementary Figure S2) to confirm the results using a second approach. Both analyses showed that there was a general clonal relationship between all strains, with the exception of the strains SAD (from South Africa) and B4102 (from the Netherlands), which supports the observation from Figure 3. These two strains clustered relatively far away (Figure 3, Supplementary Figures S1 and S2) and showed an excessive number of SNPs in relation to the type strain (1,548,865 positions were found in all analyzed genomes, 35.06% of reference genome), i.e., 7890 SNPs (strain SAD) and 4931 SNPs (strain B4102) versus 26 to 98 SNPs within the other 34 strains (type strain as reference, Supplementary Table S2).

To address the question of whether these two strains could nevertheless be unequivocally identified as H. sporothermodurans, or whether they constituted a different species, digital whole genome comparisons were performed. Digital whole genome comparisons based on average nucleotide identities (ANIs) or genome-genome-distance calculations (GGDCs) are considered as gold standard for species taxonomy [44]. Generally, a GGDH value >70% and/or an ANI >95–96% of the analyzed strain indicates that it belongs to the matching type strain [44]. The values of 84.50–90.20% GGDC and 97.70–98.38% ANIb showed that SAD and B4102 belong to the species H. sporothermodurans (Supplementary Table S1). However, a clear genetic distance from the type strain was noted when compared to all other strains, with values of 99.5–99.9% GGDH and 99.75–99.94% ANIb (Supplementary Table S1).

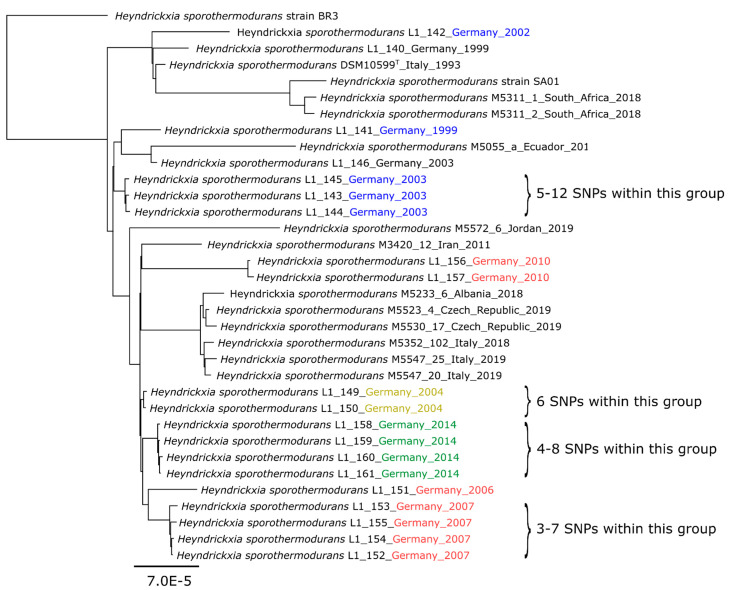

Due to these differences, the strains SAD and B4102 were not assigned to the phylogenetic “type strain group”, which consists of the majority of the H. sporothermodurans isolates and the type strain, which cluster together closely (Figure 3). A further phylogenetic analysis based on the core genes and accessory genes was done for this type strain group alone, without the less-related strains SAD and B4102, in order to obtain a more detailed view on the internal relationships of these strains (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Phylogenomic tree analysis of the H. sporothermodurans type strain group, n = 34 (Codon Tree method selects 1000 single-copy genes (PATRIC PGFams) and analyzes aligned proteins and coding DNA using the program RAxML version 8.2.11, tree was rooted to strain BR3). Isolates from the same dairy were marked in color. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site.

Overall, the type strain group has only a few SNPs (<100) and is genetically very homogeneous. Nevertheless, when looking within the type strain group at high resolution, there was also considerable heterogeneity between strains, especially evident from the strain L1_142 and L1_141 (Germany), BR3 (Brazil) and the single isolates of Ecuador, Iran and Jordan, which formed individual lineages (Figure 4).

Within the type strain group (Figure 4) there appeared to be a definite clonal relationship between strains of similar geographical origin. Thus, strains from South Africa clustered closely together, as did most strains from Germany, Italy and Czech Republic. Similarly, isolates from the same dairy at different timepoints (dairy C: L1_149, L1_150 (yellow) and dairy E: L1_158, L1_159, L1_160, L1_161 (green, Figure 4) clustered closely, together indicating a close phylogenomic relationship. Also, for isolates in dairy D (red, Figure 4) the strains grouped closely and showed a high degree of relatedness, especially when the times of isolation were close as it was the case for e.g., isolate L1_151 (isolation date 23 August 2006), L1_152/L1_153 (19 July 2007), L1_154 (17 July 2007) and L1_155 (31 July 2007). However, later isolates showed a significantly larger genetic difference (L1_156, L1_157) and cluster apart. Similarly, the blue marked isolates L1_143, L1_144, L1_145 from dairy B (Figure 4) which were isolated in a similar time period (18 June 2003, 19 August 2003, 26 August 2003) also formed a clonal lineage, which was separated from the 2 other strains L1_141 (23 June 1999) and strain L1_146 (02 December 2003), which were isolated at an earlier and later period from this dairy.

The differences in single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between the members of a closely related clade e.g., L1_152, L1_153, L1_154 and L1_155 (red) are 3–7 SNPs (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S3). In comparison, the closely related strain L1_151 (red) from the same dairy showed 13 to 17 SNPs to this group. Other highly clonal related groups exhibited 4 to 8 SNPs to each other (dairy E: L1_158, L1_159, L1_160, L1_161, green in Figure 4), 5 to 12 SNPs (dairy B: L1_143, L1_144, L1_145, blue in Figure 4) and 6 SNPs (dairy C, L1_149, L1_150, yellow in Figure 4).

In order to assess the closely related clade even more precisely, a core genome calculation within the clonally closest related isolates was performed and accessory genes were compared. The isolates L1_152, L1_153, L1_154 and L1_155 of dairy D (red) contain 3747 genes in total, of which 3418 are core genes (100% of isolates harbor these genes) and 329 are accessory (shell) genes (15–95% of isolates harbor these genes). The isolates L1_158, L1_159, L1_160 and L1_161 of dairy E (green) contain 3753 genes in total, of which 3288 are core genes and 465 are accessory genes. The isolates L1_143, L1_144 and L1_145 of dairy B (blue) contain 3969 genes in total, of which 3679 are core genes and 290 are accessory genes (shell) genes.

4. Discussion

High-throughput sequencing technology development has led to a significant improvement for the discrimination of bacteria at the genomic level. This study has extended the genome sequence data from 5 so far examined to 36 H. sporothermodurans strains, and furthermore improved the existing H. sporothermodurans (DSM 10599T) and H. oleronia (DSM 9356T) type strain genome sequences. In addition, this study is the first to present the complete genome of H. vini (JCM 19841T).

The here presented data show that a combination of short- and long-read sequencing data results in a considerable decrease of contig numbers from a few hundred to generally a single complete chromosome and thus represents a superior genome assembly approach. Using this approach, we frequently noticed an increase in genome length compared to the short-read assemblies. For H. sporothermodurans, a genome extension of 15% was achieved by long-read sequencing of the overlapping areas between the short-read contigs. At the ends of short-read contigs and in the overlapping areas, repeat regions (mobile elements, e.g., IS1182 family transposase) were frequently detected (data not shown). For species with many repetitive elements, long read sequencing is necessary to obtain the complete genome information, because repeats lead to unresolvable loops in the assembly graph that are ultimately fragmented into contigs [47,48]. It may be speculated that these repeat sequence areas are the reason for the unusually high number of contigs obtained by short-read sequencing, as it is not possible to assemble repeat regions with short-reads that occur multiple times, because short-reads alone cannot resolve repetitive genomic regions that are longer than their read length [47]. As a consequence, the numbers of small contigs, which were generated based on short-read sequencing would correlate to the number of repetitive elements present in the genome of the sequenced bacterium.

The reason for the high abundance of repeat regions in the genome of H. sporothermodurans has yet to be uncovered. However, it has been demonstrated that such regions can increase resistance of bacterial spores towards environmental stresses like heat exposure [49] and we hypothesize that similar mechanisms would explain the occurrence of repeat elements in the Heyndrickxia species presented in this study.

A striking feature of the H. sporothermodurans genome is the high degree of relationship in the respective core genes of strains, in contrast to the diversity of the respective accessory genes. Apparently, the essential core genes are much less affected by horizontal gene transfer (HGT) than the rest of the genome. In evolutionary terms, de novo mutations in Bacillus are probably less important than HGT for the variability of genomes [50,51]. For B. subtilis, it has been shown that after 504 generations up to 2% of the genome has been replaced by HGT [51]. Therefore, foreign DNA from related species was taken up and transferred or replaced by homologous recombination in integration hotspots. In our study we did not detect plasmids in the genomes, so they are less common in H. sporothermodurans and probably play a minor role in HGT. However, repeat regions that we found in H. sporothermodurans represent a general mechanism for horizontal gene transfer [50,51,52]. Core genes are not so strongly affected by this influence and remain largely stable, so that core genome and SNP analyses show a very high degree of homogeneity, although massive changes in the rest of the genome have already occurred. This would explain the very close relationship within the type strain group on the one hand; the less-related strains SAD and B4102, on the other hand, would be classified as additional clonal related lines, each forming a separate phylogenetic clade.

Two H. vini strains (previously identified on the basis of Sanger sequenced 16S rDNA analysis) could be identified as H. sporothermodurans on the basis of whole genome sequencing results. This clearly demonstrates that traditional 16S rRNA gene analysis in this case does not have sufficient resolution to discriminate between H. vini and H. sporothermodurans. The reason is probably the heterogeneity of the 16S rRNA gene copies of H. sporothermodurans, where some variants show a higher similarity to the published H. vini 16S rDNA (data not shown) than others. H. sporothermodurans and H. vini are indeed the most closely related, shown on the basis of 16S rDNA, core genes and digital whole genome comparisons (88.97% ANIb and 39.70% GGDH). Other species closely related to this H. sporothermodurans/vini clade are H. oleronia, M. shackletonii and M. camelliae. Interestingly, based on an analysis of core genes performed with 595 genes, M. shackletonii and M. camelliae form a monophyletic clade. Less related to H. sporothermodurans are Weizmannia (W.) ginsengihumi, B. acidicola, Siminovitchia (S.) fordii and Cytobacillus firmus, which deviates from previously reported work [4]. Digital DNA-DNA hybridization values between H. sporothermodurans and related strains generally support the traditional wet-lab data (Table 5) for speciation, but we found no correlation in the degree of inter-species relationships [53] in this group of bacteria. For example, DNA-DNA hybridization indicates a higher relationship between M. shackletonii and H. sporothermodurans than between H. oleronia and H. sporothermodurans, but the core genome analyses (595 genes) clearly shows a greater relationship between H. oleronia and H. sporothermodurans. As a result, DNA-DNA hybridization methods were not suitable for the determination of the degree of inter-species-relationships with values below 70%.

Table 5.

Comparison between traditional and digital DNA-DNA hybridization for Heyndrickxia sporothermodurans and closely related species.

The new classification of Bacillus species was published by Gupta et al. in 2020, which proposes a comprehensive reclassification and renaming of many Bacillus species [5]. Based on genomic comparisons, 17 distinct Bacillus species clades were identified [5]. A monophyletic clade was postulated for B. oleronius and B. sporothermodurans (Oleronius Clade), for which the genus Heyndrickxia gen. nov. was proposed [5]. Accordingly, B. oleronius was proposed to be renamed to Heyndrickxia oleronia and B. sporothermodurans to Heyndrickxia sporothermodurans [5]. Further clades were also proposed for B. shackletonii and B. camelliae (Shackletonii Clade, Margalitia gen. nov.), B. ginsengihumi (Coagulans Clade, Weizmannia gen. nov.) and B. fordii (Fordii Clade, Siminovitchia gen. nov.), among others [5]. The renaming of B. firmus into Cytobacillus firmus has also been proposed [6]. Our core genome-based analyses support the proposed monophyletic clades Oleronius and Shackletonii in general (see Figure 2). However, our data show two distinct subclades within the Oleronius clade. One subclade consists of H. sporothermodurans and H. vini, the other subclade of H. oleronia. The shared core genes from the Roary pipeline (964 core genes H. sporothermodurans -H. vini vs. 158 core genes H. sporothermodurans -H. oleronia) confirm the different species subclades. It is therefore important to include genome data such as we presented here in future taxonomical Bacillus analysis (especially H. vini). As the reclassifications were already valid (http://lpsn.dsmz.de as reference) at the time of writing, we used the new, valid species/taxon names in this study. Although the new names may initially cause some confusion, the proposed developments are justified and improve the taxonomic classification of many Bacillus species.

The intraspecies analysis of all available H. sporothermodurans genomes revealed that 34 of 36 strains belonged to the same ecotype [55], which was termed “type strain group” accordingly in this study. The bases for these groupings were the high similarities between the strains to the type strain DSM 10599T in both GGDH (>99.5%) and ANIb (>99.75%), as well as the supporting core gene homologies and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) analyses. The strains SAD and B4102 do not belong to this type strain group (2 of 36 strains) due to the results of whole-genome-comparisons, core gene and SNP analyses (e.g., GGDH < 90.2% and ANIb < 98.38%). Heyndrickx et al. [4] described a higher heterogeneity for H. sporothermodurans strains based on protein levels (SDS-page subgrouping) and wet lab DNA-DNA hybridization (76–88%). There, the authors analyzed H. sporothermodurans strains from different origins (UHT-milk, raw milk, soy, feed concentrate, pulp, silage), while only UHT-milk isolates were used in the present study. The limited strain variation detected here indicates that UHT-processing treatment of raw milk results in the selection of a specific ecotype.

It is difficult to provide a satisfactory answer to the question of whether and how long a strain may persist in a single dairy, or whether there are new contaminating strains being continually brought into the dairy. It can, however, be speculated that isolate L1_151 persisted in dairy D and developed into the clonal related strains L1_152, L1_153, L1_154, L1_155 (3–7 SNPs) within the 11 months these strains were isolated. The SNPs between isolate L1_151 (origin) and L1_152, L1_153, L1_154, L1_155 were 18, 16, 21, 22 SNPs, respectively. However, this does not correspond with the times of sampling, if accumulation of SNPs during time would be assumed. Additionally, the clonal isolates L1_152, L1_153, L1_154 and L1_155 harbor 3418 core and 329 accessory genes. This was quite a surprising high rate of accessory genes for strains with such low numbers of 3–7 SNPs in their core genomes. One explanation would be the coexistence and coevolution of different H. sporothermodurans strains in one dairy, even if they descended from a common ancestor. This coevolution of different strains can lead to the accumulation of SNPs at different speeds over time [56]. Furthermore, it has been shown by Dettling et al. that spore formers can persist for up to 24 months in milk powder processing lines [56].

The strains from Germany also showed individual clusters in which strains showed clonal relationships, but different clusters of German strains also showed that these probably presented individual lineages (Figure 3). A remarkable observation from a previous study done with a limited set of isolates showed that one clone, termed HRS, was involved in the majority of the cases of UHT milk spoilage [14]. Indeed, when looking at individual clusters in this study up close, clonal relationship could also be determined between strains, often when these were isolated in the same or in consecutive years (Figure 4). There seems to be not just one dominant clone in a specific dairy processing plant, but a parallel development from an original ancestor. As an example, isolates L1_158, L1_159, L1_160, L1_161 from a single dairy show differences from 4 to 8 SNPs (between the strains), although all were isolated on the same day. On the other hand, there are 4 months between the sampling of isolates L1_149, L1_150, which differ only by 6 SNPs (Supplementary Table S3).

In general, there is no strict rule for a separation between the terms clone and strain. For Listeria (L.) monocytogenes outbreak analysis, the distances are set at 4 to 25 (up to 63) SNPs for a clonal line, depending on the species and outbreak period (isolation time spanned several months or years) [52]. Other authors concluded that L. monocytogenes strains with under 10 SNPs can occur in different retail deli environments without any links of known transmission [57]. Today, direct clones should have almost no SNPs, since the sequencing errors are very small [23].

Only when horizontal gene transfer and the core genome are evaluated together, is it possible to distinguish between strain and clonal line [52]. Here, we can assume for the isolates with <10 SNPs difference in their genomes are classified as clonal lines derived from the same strain. More than 10 SNPs indicates a close relationship but corresponding isolates likely belong to a different strain. In this sense, the isolates L1_158, L1_159, L1_160, L1_161 (4 to 8 SNPs) belong to one strain, also L1_149, L1_150 (6 SNPs), L1_156, L1_157 (4 SNPs) and L1_152, L1_153, L1_154, L1_155 (3–7 SNPs) and so on. However, this is a very arbitrary classification, whose scientific basis is highly debatable and which is only mentioned here for the sake of completeness.

However, this very close relationship indicates, that due to the high thermotolerance of their spores, bacteria persist within a milk processing environment for long time periods of up to several months. Moreover, the occurrence of phylogenetic clusters often correlated with their respective geographic origin, indicating that these heat-resistant bacteria not only co-exist for extended periods of time in specific milk processing environments, but also display a similar dissemination behavior between closely located processing environments. Supporting this assumption, we determined one monophyletic cluster containing highly related strains, which originated from proximal geographic sites, i.e., Italy, Albania and Czech Republic.

It is unclear which physiological adaptations (heat resistance, spore production, biofilm formation, etc.) were triggered by the genetic changes. For this, further studies should be carried out, if possible with a greater heterogeneity of strains. Determining the heat resistance of the spores is one of the important points to clarify if some clusters are more heat resistant than others. It is possible that isolates from one dairy may become more resistant over time. These results on heat resistance should then be compared with the genomic and genomic change (i.e., evolutionary) data, similar to those presented in this study. Also, the heat resistance of H. vini spores has not been estimated so far, this should also be done in future investigations. Thermal preservation is of great importance for the food industry. If the thermal processes are not sufficient for spore-inactivation, this can lead to premature food spoilage. Our investigations show the persistence of H. sporothermodurans for months in food processing plants. For this reason, molecular detection systems should also be developed for selective and sensitive detection of H. sporothermodurans and other relevant Bacillus species contamination to prevent financial losses for companies from loss of quality of the processed milk products.

5. Conclusions

This study presents the complete genomes of the type strains H. sporothermodurans DSM 10599T, H. oleronia DSM 9356T and H. vini JCM 19841T as well as the genomes of 31 H. sporothermodurans strains isolated from UHT-treated milk from different continents. This study is the first to present the complete genome of H. vini (JCM 19841T). The type strains (H. sporothermodurans, H. oleronia and H. vini) were clustered into one phylogenetic clade, whereby H. sporothermodurans was more closely related to H. vini than to H. oleronia. Moreover, this clade was found to be distinct from the M. shackletonii and M. camelliae cluster.

Previous work reported difficulties in assembling Heyndrickxia species genomes using a short-read sequencing approach [13,18,20]. Therefore, we utilized hybrid assembly of Illumina short-read and MinION long-read sequences of type strain H. sporothermodurans DSM 10599T, which mostly yielded a single coherent chromosome sequence instead of a few hundred contigs. Furthermore, genome size and G + C value differed significantly between both assembly approaches. We could detect a major increase in genome length and a minor increase in the mol% G + C content. The high amount of contigs obtained after short-read sequencing is probably caused by the occurrence of mobile elements which are overrepresented in H. sporothermodurans. As the assembly of genomes containing multiple repetitive genetic elements can be challenging, this species can be considered a model organism for improving and evaluating sequencing methods and assemblies.

Furthermore, a high clonal relationship of core genes was shown in 34 of 36 H. sporothermodurans strains, which were classified as type strain group accordingly. The remaining two strains (SAD and B4102) could be identified as H. sporothermodurans as well, based on digital whole genome comparison. Nevertheless, both strains probably belong to distinct phylogenetic clades due to their clear genetic distance from the type strain group.

In conclusion, our results indicate that clonally related isolates with <10 SNPs occur in the course of few months in industrial dairy environments and can persist and (co)evolve quickly. Therefore, this study represents the basis for the development of detection systems and avoidance strategies to prevent contamination of food with highly heat-resistant spore formers like H. sporothermodurans.

Acknowledgments

The technical assistance of Petra Horn and the help of Frank Hille is gratefully acknowledged.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/9/2/246/s1, Table S1: The genome’s core and accessory genes, Table S2: Overview about the genome-to-genome calculations and the number of SNPs from all H. sporothermodurans strains and H. vini and H. oleronia, Table S3: Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) matrix of 36 H. sporothermodurans strains; Figure S1: Phylogenetic tree analysis of 36 H. sporothermodurans strains based on core genes, Figure S2: Phylogenetic tree analysis of 36 H. sporothermodurans strains based on SNPs, Figure S3: Detailed phylogenetic tree analysis of 34 H. sporothermodurans strains based on SNPs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B., M.W. and G.F.; methodology, G.F.; software, G.F.; validation, G.F.; for-mal analysis, A.-D.H. and G.F.; investigation, A.-D.H. and G.F.; resources, C.M.A.P.F., F.B., M.L., E.B.; data curation, G.F.; writing—original draft preparation, G.F., C.M.A.P.F.; writing—review and editing, A.-D.H., E.D., M.W., C.B., C.M.A.P.F., E.B., J.K., F.B., M.L.; visualization, G.F.; su-pervision, C.B. and G.F.; project administration, C.B.; funding acquisition, J.K., C.B., M.W., C.M.A.P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Federal Ministry for Food and Agriculture (BMEL based on a decision of the Parliament of the Federal Republic of Germany via the Federal Office for Agriculture and Food (BLE) under the innovation support program (281A105616).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pettersson B., Lembke F., Hammer P., Stackebrandt E., Priest F.G. Bacillus sporothermodurans, a new species producing highly heat-resistant endospores. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1996;46:759–764. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-3-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhnigk T., Borst E.M., Breunig A., König H., Collins M.D., Hutson R.A., Kämpfer P. Bacillus oleronius sp.nov., a member of the hindgut flora of the termite Reticulitermes santonensis (Feytaud) Can. J. Microbiol. 1995;41:699–706. doi: 10.1139/m95-096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma K., Chen X., Guo X., Wang Y., Wang H., Zhou S., Song J., Kong D., Zhu J., Dong W., et al. Bacillus vini sp. nov. isolated from alcohol fermentation pit mud. Arch. Microbiol. 2016;198:559–564. doi: 10.1007/s00203-016-1218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heyndrickx M., Coorevits A., Scheldeman P., Lebbe L., Schumann P., Rodríguez-Diaz M., Forsyth G., Dinsdale A., Heyrman J., Logan N.A., et al. Emended descriptions of Bacillus sporothermodurans and Bacillus oleronius with the inclusion of dairy farm isolates of both species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2012;62:307–314. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.026740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta R.S., Patel S., Saini N., Chen S. Robust demarcation of 17 distinct Bacillus species clades, proposed as novel Bacillaceae genera, by phylogenomics and comparative genomic analyses: Description of Robertmurraya kyonggiensis sp. nov. and proposal for an emended genus Bacillus limiting it only to the members of the Subtilis and Cereus clades of species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020;70:5753–5798. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.004475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel S., Gupta R.S. A phylogenomic and comparative genomic framework for resolving the polyphyly of the genus Bacillus: Proposal for six new genera of Bacillus species, Peribacillus gen. nov., Cytobacillus gen. nov., Mesobacillus gen. nov., Neobacillus gen. nov., Metabacillus gen. nov. and Alkalihalobacillus gen. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020;70:406–438. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammer P., Suhren G., Heeschen W. Pathogenicity Testing of Unknown Mesophilic Heat Resistant Bacilli from UHT-Milk [Heat Resistant Mesophilic Sporeformes or HRS], 1995. Bull. FIL IDF. 2012;302:56–57. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammer P., Lembke F., Suhren G., Heeschen W. Characterization of a heat resistant mesophilic Bacillus species affecting quality of UHT-milk: A preliminary report. Kiel. Milchwirtsch. Forsch. 1995;47:297–305. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaerewijck M.J., de Vos P., Lebbe L., Scheldeman P., Hoste B., Heyndrickx M. Occurrence of Bacillus sporothermodurans and other aerobic spore-forming species in feed concentrate for dairy cattle. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001;91:1074–1084. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lücking G., Stoeckel M., Atamer Z., Hinrichs J., Ehling-Schulz M. Characterization of aerobic spore-forming bacteria associated with industrial dairy processing environments and product spoilage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013;166:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aouadhi C., Maaroufi A., Mejri S. Incidence and characterisation of aerobic spore-forming bacteria originating from dairy milk in Tunisia. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2014;67:95–102. doi: 10.1111/1471-0307.12088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klijn N., Herman L., Langeveld L., Vaerewijck M., Wagendorp A.A., Huemer I., Weerkamp A.H. Genotypical and phenotypical characterization of Bacillus sporothermodurans strains, surviving UHT sterilisation. Int. Dairy J. 1997;7:421–428. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(97)00029-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheldeman P., Pil A., Herman L., de Vos P., Heyndrickx M. Incidence and diversity of potentially highly heat-resistant spores isolated at dairy farms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:1480–1494. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1480-1494.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillaume-Gentil O., Scheldeman P., Marugg J., Herman L., Joosten H., Heyndrickx M. Genetic heterogeneity in Bacillus sporothermodurans as demonstrated by ribotyping and repetitive extragenic palindromic-PCR fingerprinting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:4216–4224. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.9.4216-4224.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krawczyk A.O., de Jong A., Holsappel S., Eijlander R.T., van Heel A., Berendsen E.M., Wells-Bennik M.H.J., Kuipers O.P. Genome Sequences of 12 Spore-Forming Bacillus Species, Comprising Bacillus coagulans, Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus sporothermodurans, and Bacillus vallismortis, Isolated from Foods. Genome Announc. 2016 doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00103-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kmiha S., Aouadhi C., Klibi A., Jouini A., Béjaoui A., Mejri S., Maaroufi A. Seasonal and regional occurrence of heat-resistant spore-forming bacteria in the course of ultra-high temperature milk production in Tunisia. J. Dairy Sci. 2017;100:6090–6099. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-11616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herman L.M., Vaerewijck M.J., Moermans R.J., Waes G.M. Identification and detection of Bacillus sporothermodurans spores in 1, 10, and 100 milliliters of raw milk by PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997;63:3139–3143. doi: 10.1128/AEM.63.8.3139-3143.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheldeman P., Herman L., Goris J., de Vos P., Heyndrickx M. Polymerase chain reaction identification of Bacillus sporothermodurans from dairy sources. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2002;92:983–991. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheldeman P., Herman L., Foster S., Heyndrickx M. Bacillus sporothermodurans and other highly heat-resistant spore formers in milk. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006;101:542–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owusu-Darko R., Allam M., Mtshali S., Ismail A., Buys E.M. Draft genome sequence of Bacillus oleronius DSM 9356 isolated from the termite Reticulitermes santonensis. Genom. Data. 2017;12:76–78. doi: 10.1016/j.gdata.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auch A.F., von Jan M., Klenk H.-P., Göker M. Digital DNA-DNA hybridization for microbial species delineation by means of genome-to-genome sequence comparison. Stand. Genom. Sci. 2010;2:117–134. doi: 10.4056/sigs.531120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owusu-Darko R., Allam M., de Oliveira S.D., Ferreira C.A.S., Grover S., Mtshali S., Ismail A., Mallappa R.H., Tabit F., Buys E.M. Genome Sequences of Bacillus sporothermodurans Strains Isolated from Ultra-High-Temperature Milk. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2019 doi: 10.1128/MRA.00145-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uelze L., Borowiak M., Bönn M., Brinks E., Deneke C., Hankeln T., Kleta S., Murr L., Stingl K., Szabo K., et al. German-Wide Interlaboratory Study Compares Consistency, Accuracy and Reproducibility of Whole-Genome Short Read Sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:573972. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.573972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiedler G., Kabisch J., Brinks E., Sprotte S., Boehnlein C., Franz C.M.A.P. Complete Genome Sequence of a Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli O26:H11 Strain (Sequence Type 21) and Two Draft Genome Sequences of Listeria monocytogenes Strains (Clonal Complex 1 [CC1] and CC59) Isolated from Fresh Produce in Germany. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2020 doi: 10.1128/MRA.00973-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiedler G., Ballem A., Brinks E., Almeida C., Franz C.M.A.P., Oliveira H. Draft Genome Sequences of 12 Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Dairy Cattle in Portugal. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2020 doi: 10.1128/MRA.00790-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiedler G., Schneider C., Igbinosa E.O., Kabisch J., Brinks E., Becker B., Stoll D.A., Cho G.-S., Huch M., Franz C.M.A.P. Antibiotics resistance and toxin profiles of Bacillus cereus-group isolates from fresh vegetables from German retail markets. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:250. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1632-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis J.J., Wattam A.R., Aziz R.K., Brettin T., Butler R., Butler R.M., Chlenski P., Conrad N., Dickerman A., Dietrich E.M., et al. The PATRIC Bioinformatics Resource Center: Expanding data and analysis capabilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D606–D612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee I., Chalita M., Ha S.-M., Na S.-I., Yoon S.-H., Chun J. ContEst16S: An algorithm that identifies contaminated prokaryotic genomes using 16S RNA gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017;67:2053–2057. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Coster W., D’Hert S., Schultz D.T., Cruts M., van Broeckhoven C. NanoPack: Visualizing and processing long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:2666–2669. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wattam A.R., Davis J.J., Assaf R., Boisvert S., Brettin T., Bun C., Conrad N., Dietrich E.M., Disz T., Gabbard J.L., et al. Improvements to PATRIC, the all-bacterial Bioinformatics Database and Analysis Resource Center. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D535–D542. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tatusova T., DiCuccio M., Badretdin A., Chetvernin V., Nawrocki E.P., Zaslavsky L., Lomsadze A., Pruitt K.D., Borodovsky M., Ostell J. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:6614–6624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haft D.H., DiCuccio M., Badretdin A., Brover V., Chetvernin V., O’Neill K., Li W., Chitsaz F., Derbyshire M.K., Gonzales N.R., et al. RefSeq: An update on prokaryotic genome annotation and curation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D851–D860. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seemann T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Page A.J., Cummins C.A., Hunt M., Wong V.K., Reuter S., Holden M.T.G., Fookes M., Falush D., Keane J.A., Parkhill J. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Afgan E., Baker D., Batut B., van den Beek M., Bouvier D., Čech M., Chilton J., Clements D., Coraor N., Grüning B.A., et al. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W537–W544. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meier-Kolthoff J.P., Auch A.F., Klenk H.-P., Göker M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meier-Kolthoff J.P., Göker M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2182. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10210-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edgar R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goloboff P.A., Farris J.S., Nixon K.C. TNT, a free program for phylogenetic analysis. Cladistics. 2008;24:774–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2008.00217.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pattengale N.D., Alipour M., Bininda-Emonds O.R.P., Moret B.M.E., Stamatakis A. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? J. Comput. Biol. 2010;17:337–354. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2009.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cock P.J.A., Antao T., Chang J.T., Chapman B.A., Cox C.J., Dalke A., Friedberg I., Hamelryck T., Kauff F., Wilczynski B., et al. Biopython: Freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1422–1423. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richter M., Rosselló-Móra R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:19126–19131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906412106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chun J., Oren A., Ventosa A., Christensen H., Arahal D.R., da Costa M.S., Rooney A.P., Yi H., Xu X.-W., de Meyer S., et al. Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018;68:461–466. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaas R.S., Leekitcharoenphon P., Aarestrup F.M., Lund O. Solving the problem of comparing whole bacterial genomes across different sequencing platforms. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e104984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saltykova A., Wuyts V., Mattheus W., Bertrand S., Roosens N.H.C., Marchal K., de Keersmaecker S.C.J. Comparison of SNP-based subtyping workflows for bacterial isolates using WGS data, applied to Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium and serotype 1,4,5,12:i. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0192504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cahill M.J., Köser C.U., Ross N.E., Archer J.A.C. Read length and repeat resolution: Exploring prokaryote genomes using next-generation sequencing technologies. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldstein S., Beka L., Graf J., Klassen J.L. Evaluation of strategies for the assembly of diverse bacterial genomes using MinION long-read sequencing. BMC Genom. 2019;20:23. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5381-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berendsen E.M., Boekhorst J., Kuipers O.P., Wells-Bennik M.H.J. A mobile genetic element profoundly increases heat resistance of bacterial spores. ISME J. 2016;10:2633–2642. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palmer M., Venter S.N., Coetzee M.P.A., Steenkamp E.T. Prokaryotic species are sui generis evolutionary units. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2019;42:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slomka S., Françoise I., Hornung G., Asraf O., Biniashvili T., Pilpel Y., Dahan O. Experimental Evolution of Bacillus subtilis Reveals the Evolutionary Dynamics of Horizontal Gene Transfer and Suggests Adaptive and Neutral Effects. Genetics. 2020;216:543–558. doi: 10.1534/genetics.120.303401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palma F., Brauge T., Radomski N., Mallet L., Felten A., Mistou M.-Y., Brisabois A., Guillier L., Midelet-Bourdin G. Dynamics of mobile genetic elements of Listeria monocytogenes persisting in ready-to-eat seafood processing plants in France. BMC Genom. 2020;21:130. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-6544-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goris J., Konstantinidis K.T., Klappenbach J.A., Coenye T., Vandamme P., Tiedje J.M. DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007;57:81–91. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Albert R.A., Archambault J., Rosselló-Mora R., Tindall B.J., Matheny M. Bacillus acidicola sp. nov., a novel mesophilic, acidophilic species isolated from acidic Sphagnum peat bogs in Wisconsin. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005;55:2125–2130. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Konstantinidis K.T., Tiedje J.M. Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:2567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409727102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dettling A., Wedel C., Huptas C., Hinrichs J., Scherer S., Wenning M. High counts of thermophilic spore formers in dairy powders originate from persisting strains in processing lines. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020;335:108888. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2020.108888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stasiewicz M.J., Oliver H.F., Wiedmann M., den Bakker H.C. Whole-Genome Sequencing Allows for Improved Identification of Persistent Listeria monocytogenes in Food-Associated Environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:6024–6037. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01049-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.