Abstract

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, high-grade, aggressive cutaneous neuroendocrine malignancy most commonly associated with sun-exposed areas of older individuals. A relatively newly identified human virus, the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of MCC. Our study aimed to examine nine MCC cases and randomly selected 60 melanoma cases to identify MCPyV status and to elucidate genetic differences between virus-positive and -negative cases. Altogether, seven MCPyV-positive MCC samples and four melanoma samples were analyzed. In MCPyV-positive MCC RB1, TP53, FBXW7, CTNNB1, and HNF1A pathogenic variants were identified, while in virus-negative cases only benign variants were found. In MCPyV-positive melanoma cases, besides BRAF mutations the following genes were also affected: PIK3CA, STK11, CDKN2A, SMAD4, and APC. In contrast to studies found in the literature, a higher tumor burden was detected in virus-associated MCC compared to MCPyV-negative cases. No association was identified between virus infection and tumor burden in melanoma samples. We concluded that analyzing the key morphologic and immunohistological features of MCC is critical to avoid confusion with other cutaneous malignancies. Molecular genetic investigations such as next-generation sequencing (NGS) enable molecular stratification, which may have future clinical impact.

Keywords: Merkel cell carcinoma, Merkel cell polyomavirus, melanoma, molecular genetics, next-generation sequencing (NGS)

1. Introduction

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, high-grade, aggressive primary cutaneous neuroendocrine malignancy causing rapidly enlarging lesions on sun-exposed areas of older Caucasian individuals [1,2]. The incidence of MCC has increased over the past 30 years due to the aging population, the additional reporting, and improvements in diagnostic techniques [3]. The incidence ranges from 0.1 to 1.6 cases per 100,000 people per year [4,5]. The rising incidence with its often rapidly aggressive course underscores a critical need to analyze the histopathologic and the immunohistochemical (IHC) features of the disease. MCC was regarded as a dermal malignancy that often involves the subcutis. The tumor cells of MCC show a characteristic neuroendocrine cytomorphology with scant cytoplasm and uniform round to oval nuclei., show in the majority of cases, positivity for cytokeratin 20 (CK20), synaptophysin, chromogranin A (CHGA), and neurofilament (NF), but often negative for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) [6].

A relatively newly identified human virus, the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV), has been implicated in the pathogenesis of MCCs [7]. The virus appears to be causative in most cases and it was applied as a diagnostic and prognostic marker [6]. MCPyV is present in around 60–80% of MCC and only in 11% of control tissues within their majority lower copy numbers [8]. Some studies published molecular aberrations that can play a role in the virus-associated MCC malignancy such as KIT, PIK3CA, and genes in the Hedgehog signal transduction pathway [9,10,11]. In other forms of MCC in which MCPyV cannot be detected, supposing the ultraviolet light exposure represents key drivers in the carcinogenesis [6]. MCPyV-negative MCCs are described by a higher mutation burden compared to MCPyV-positive MCC, and these mutations can be considered UV-signature variations. The most relevant alterations in virus-negative cases affect NOTCH, RB1, and TP53 genes [12,13]. In geographic regions with less UV exposure, MCC is more common with MCPyV positivity, whereas in areas with relatively high UV exposure, MCPyV-negative MCCs predominate [14].

Due to limited data available for molecular study in MCCs, particularly with next-generation sequencing (NGS) methods, the aim of our study was (1) to detect the MCPyV status of nine MCC patients, diagnosed from three separate institutes, (2) to compare the molecular differences between virus-positive and -negative subgroups, (3) to identify MCPyV frequency in other randomly selected cutaneous melanoma, and (4) to elucidate genetic differences between virus-associated and -negative cases and MCPyV-associated melanoma samples as well. For this purpose, histology examination, diagnostic IHC including antibody against large T antigen of MCPyV, MCPyV-specific PCR, and NGS with solid tumor gene panel analysis were performed using MCC and MCPyV-associated melanoma samples. Additionally, reverse-hybridization StripAssay was carried out on melanoma samples detecting BRAF mutation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients’ Samples

Altogether, nine formaldehyde-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue (FFPE) MCCs and 60 control melanoma samples were tested. All protocols were approved by the authors’ respective Institutional Review Board for human subjects (IRB reference number: 60355/2016/EKU).

2.2. Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides were carefully analyzed and validated by pathology specialists and appropriate tumor samples were selected for DNA isolation with a tumor percentage >20%. IHC of CK20 (clone Ks20.8, 1:200 dilution, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), synaptophysin (clone 27G12, 1:100 dilution, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), CHGA (clone DAK-A3, 1:400 dilution, Dako, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and TTF-1 (clone SPT24, 1:100 dilution, BioCare Medical, Pacheco, CA, USA) was performed to confirm MCC diagnosis. For the differential diagnosis in melanoma cases, S100 protein (polyclonal, 1:1000 dilution, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), vimentin (clone V9, 1:200 dilution, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), HMB45 (Human Melanoma Black, clone HMB-45, 1:200 dilution, Dako, Agilent Technologies Company, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and Melan-A (clone A103, 1:200 dilution, Dako, Agilent Technologies Company, Santa Clara, CA, USA) antibody was used. MCPyV immunological detection was carried out using MCPyV large T-antigen antibody (clone CM2B4, 1:100 dilution, Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Additional staining for Ki-67 (clone MIB1, 1:200 dilution, Dako, Agilent Technologies Company, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was done to determine the cell proliferation index. The p53 antibody (clone Do-07, 1:700 dilution, Dako, Agilent Technologies Company, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was applied to compare immune positivity with molecular genetic findings in MCC cases.

2.3. DNA Isolation

Genomic DNA was extracted from FFPE tissues using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The isolations were carried out according to the manufacturer’s standard protocol and the DNA was eluted in 50 µL elution buffer. The DNA concentration was measured in the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit using a Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.4. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Molecular Detection

For virus T antigen and/or viral capsid DNA sequences in the nine MCC and 60 histopathological similar cutaneous malignant melanoma samples, LT1 (large T1), LT3 (large T3), and VP1 (viral capsid protein 1) primer pairs were used. The DNA amplification was carried out according to the earlier study [15]. To demonstrate that the quality and quantity of the DNA samples were acceptable, the human β-globin gene was also amplified.

2.5. BRAF StripAssay

Reverse hybridization was carried out using BRAF 600/601 StripAssay according to the manufacturer’s protocol (ViennaLab Diagnostics, Vienna, Austria). The assay covers nine clinically relevant mutations in the BRAF gene and is certified for human in vitro diagnostics (IVD). For interpretation, hybridization strips were aligned using the standardized layout supplied with the reagents, and positive bands were identified.

2.6. Next-Generation Sequencing

The amount of amplifiable DNA (ng) was calculated according to the Archer PreSeq DNA Calculator Assay Protocol (Archer DX, Boulder, CO, USA). After the fragmentation of the genomic DNA, libraries were created by the Archer VariantPlex Solid Tumor Kit (Archer DX, Boulder, CO, USA). The KAPA Universal Library Quantification Kit (Kapa Biosystems, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) was used for the final quantification of the libraries.

The MiSeq System (MiSeq Reagent kit v3 600 cycles, Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for sequencing. The libraries (final concentration of 4 nM, pooled by equal molarity) were denatured by adding 0.2 nM NaOH and diluted to 40 pM with hybridization buffer from Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA). The final loading concentration was 8 pM libraries and 1% PhiX. Sequencing was conducted according to the MiSeq instruction manual. Captured libraries were sequenced in a multiplexed fashion with a paired-end run to obtain 2 ×150 bp reads with at least 250× depth of coverage. The trimmed fastq files were generated using MiSeq reporter (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Raw sequence data were analyzed with Archer analysis software (version 6.2.; Archer DX, Boulder, CO, USA) for the presence of single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) as well as insertions and deletions (indels). For the alignment, the human reference genome GRCh37 (equivalent UCSC version hg19) was built. Molecular barcode (MBC) adapters were used to count unique molecules and characterize sequencer noise, revealing mutations below standard NGS-based detection thresholds. The sequence quality for each sample was assessed and the cutoff was set to 5% variant allele frequency (VAF). VAF is the percentage of sequence reads observed matching a specific DNA variant divided by the overall coverage at that locus. Large insertion/deletion (>50 bp) and complex structural changes could not be captured by the method. The results were described using the latest version of the Human Genome Variation Society nomenclature for either the nucleotide or protein level. Individual gene variants were cross-checked in the COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) and ClinVar databases for clinical relevance. We used gnomAD v.2.1.1 population database to compare the significance of each gene alteration, which is included in our Archer NGS analysis system.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Presentations

The clinical features of the MCC patients are shown in Table 1. The average age of the nine MCC patients was 77.8 (range: 63–89). The gender distribution was six male and three female. The localization of the tumor was more frequent in the sun-exposed regions than in other areas (e.g., gluteus). The average tumor size was 2.4 cm (range: 1–6 cm) and the mean tumor depth was 1.7 cm (range: 0.4–6.7 cm). The oncological treatments included excision, chemotherapy, and/or radiotherapy.

Table 1.

Oncological characteristics of the Merkel cell carcinoma patients.

| Patient | Gender | Age (years) | Location | Size (cm) | Depth (cm) | Treatment | Metastasis | Survival (Month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 89 | left knee | 4 | 1 | excision and chemotherapy | n.a. | 7 |

| 2 | M | 80 | right face | 1.5 | 0.9 | excision | lost follow-up | |

| 3 | M | 88 | right chest | 2.2 | 0.5 | excision | lost follow-up | |

| 4 | F | 68 | left shoulder | 1.1 | 0.7 | neoadjuvant chemotherapy | axillary lymph node | 24 |

| 5 | M | 83 | right thigh | 2.4 | 2.2 | excision | lost follow-up | |

| 6 | M | 76 | right 3rd finger | 1 | 6.7 | excision | n.a. | 9 |

| 7 | F | 85 | right face | 1.4 | 1.6 | radiotherapy | lost follow-up | |

| 8 | F | 63 | right gluteus | 2 | 0.4 | radiotherapy | n.a. | 6 |

| 9 | M | 68 | right forearm | 6 | 1 | excision | lymp node | 3 |

3.2. Histological Features Including Immunohistochemistry

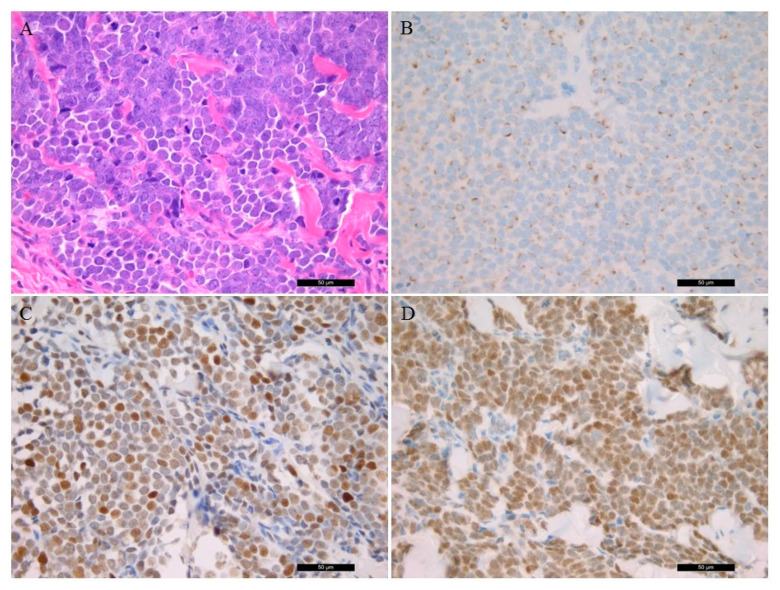

The tumor cells of MCC show uniform, small, blue, round cells with high nuclear/ cytoplasmic ratio with granular chromatin and numerous nucleoli (Figure 1A). Histopathological characteristics of the patient samples are presented in Table 2. Cell proliferation ratio was determined above 50%. CK20 (usually dot-like) (Figure 1B), synaptophysin, and CHGA positivity were found, while no TTF-1 expression was detected in all cases. Lymphovascular invasion was present in two cases. The p53 IHC was positive in six samples (Figure 1C). Vimentin and S100 protein positivity was detected in all melanoma samples.

Figure 1.

Histological and immunostaining of Merkel Cell Carcinoma (40×). (A) Conventional histological hematoxylin and eosin-stained characteristics of the tumor sample; (B) immunohistochemistry of CK20 protein; (C) p53 immunostaining; (D); Merkel cell polyomavirus large T antigen-positive tumor sample.

Table 2.

Immunohistopathological and PCR features of the MCC patients.

| Cases | Lymphocyte Infiltration | Ki-67 (%) | Cytokeratin 20 | Synaptophysin | Chromogranin A | Thyroid Transcription Factor 1 | p53 | MCPyV IHC | LT1 PCR |

LT3 PCR |

VP1 PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | low | 60 | + | + | + | - | diffuse + | + | - | + | + |

| 2 | low | 60 | + | + | + | - | patchy + | + | - | + | + |

| 3 | low | 50 | + | + | - | - | diffuse + | - | - | - | + |

| 4 | low | 60 | dot-like | marked | marked | - | - | diffuse + | - | + | - |

| 5 | low | 80 | dot-like | marked | focal | - | weakly + | - | - | - | - |

| 6 | moderate | 70 | dot-like | marked | marked | - | - | patchy + | - | + | - |

| 7 | low | 60 | dot-like | dot-like | dot-like | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 8 | moderate | 70 | dot-like | + | patchy + | - | diffuse + | - | - | + | - |

| 9 | low | 60 | dot-like | dot-like | dot like | - | patchy + | diffuse + | - | + | + |

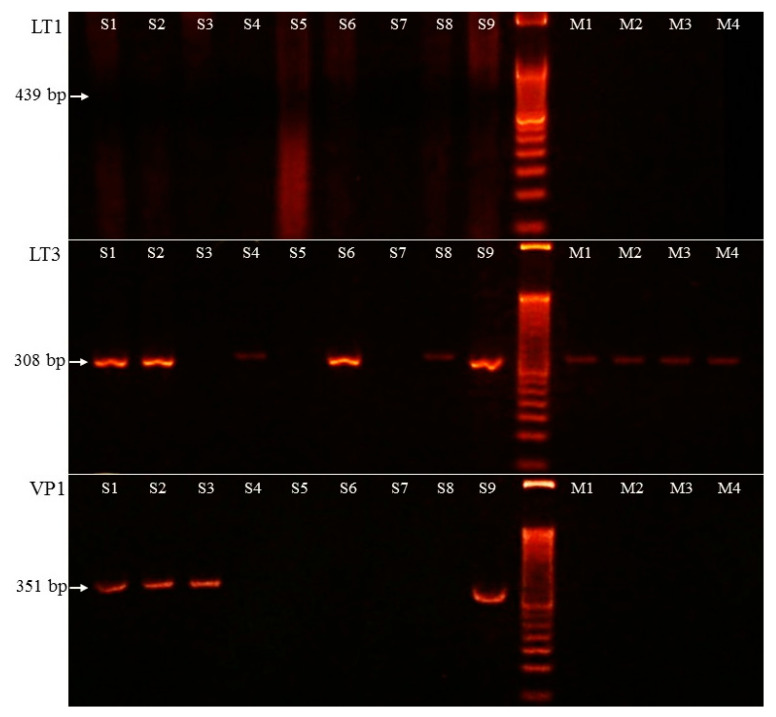

3.3. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Detection

MCPyV was detected with two methods. Five MCC samples were positive for the MCPyV antibody (Figure 1D). PCR amplification of the viral large T protein LT3 (amplification product size 308 bp) was positive in six cases. Additionally, in one case (case 3), only the viral capsid protein VP1 (351 bp) was positive, as well. The LT1 (439 bp) PCR was negative in all cases. Altogether, seven MCPyV-positive MCC samples were detected using PCR (7/9, 77.8% vs. 5/9, 55.6% MCPyV IHC). IHC staining had limited sensitivity in case 8 because the viral LT genome sequence was detected by PCR. In case 3 the virus LT antigene IHC did not detect positivity, aiming at viral capsid protein being present when using PCR amplification.

Two types of agarose electrophoresis lane intensity were detected and high virus copy number samples were characterized with a robust band (samples 1, 2, 6, and 9), while samples 4 and 8 showed weak stripe and, consequently, low virus copy number. The MCPyV LT3 and VP1 PCR results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

PCR amplification results of Merkel cell polyomavirus LT1 (large T1), LT3 (large T3), and VP1 (viral capsid protein 1) sequence. S1–S9: Merkel cell carcinoma samples, M1–M4: melanoma samples. PCR amplification product sizes: 439 bp (LT1), 308 bp (LT3), and 351 bp (VP1).

3.4. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Amplification in Melanoma Samples

PCR amplification of LT1, LT3, and VP1 virus genes was carried out on 60 melanoma DNA samples. LT3 was present in four melanoma samples with a low copy number (6.7%), opposite to LT1 and VP1, where no PCR product was amplified.

The melanoma samples were analyzed for BRAF mutation status using StripAssay. Thirty BRAF mutations were identified. In 22 cases BRAF c.1799T>A; p.(Val600Glu) (36.7%) and in seven samples (11.7%) the c.1798_1799GT>AA; p.(Val600Lys) mutation was detected, while in one case (1.7%) the c.1799_1780TG>AA; p.(Val600Glu) aberration was present. LT3 amplification (4/30, 13.3%) was detected only in the BRAF+ group with Val600Lys amino acid change. The amplification result of the four MCPyV-positive melanoma cases is presented in Figure 2.

3.5. NGS-Based Mutation Profiling

The 67 genes’ solid tumor panel analysis identified a series of alterations in the affected genes. The NGS analysis results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Molecular genetic NGS findings of MCC and melanoma samples. The clinical significance of gene variants was checked in the COSMIC database. The ID of nucleotide and amino acid changes were included in the table. S1–S9: Merkel cell carcinoma samples, M1–M3: melanoma samples. The PCR results of MCPyV status are presented in parentheses.

| Scheme | Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Nucleotide Change | Amino Acid Change | Variant Allele Frequency (%) | Clinical Sgnificance | COSMIC ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 (+) | RB1 | retinoblastoma 1 | c.2033A>T | p.His678Leu | 48 | no data available | - |

| S2 (+) | STK11 | serine/threonine kinase 11 | c.1062C>G | p.Phe354Leu | 54.55 | neutral | COSM21360 |

| S3 (+) | EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor | c.2137G>A | p.Glu713Lys | 30.25 | no data available | - |

| FBXW7 | F-box/WD repeat-containing protein 7 | c.1031C>T | p.Ser344Phe | 89.3 | COSM1177864 | ||

| TP53 | tumor protein P53 | c.832C>T | p.Pro278Ser | 92.4 | pathogenic | COSM10939 | |

| S4 (+) | CTNNB1 | catenin beta-1 | c.59C>T | p.Ala20Val | 9 | pathogenic | COSM5702 |

| S5 (-) | CDKN2A | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A | c.442G>A | p.Ala148Thr | 50 | neutral | COSM3774362 |

| FGFR1 | fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 | c.2181-6C>T | - | 48.6 | no data available | - | |

| S6 (+) | ABL1 | tyrosine-protein kinase ABL1 | c.740A>G | p.Lys247Arg | 42.1 | benign | - |

| FOXL2 | forkhead box protein L2 | c.536C>G | p.Ala179Gly | 65.3 | benign | COSM4600643 | |

| HNF1A | hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 A | c.864del | p.Pro291GlnfsTer51 | 7.5 | pathogenic | COSM935974 | |

| S7 (-) | no mutation detected | ||||||

| S8 (+) | JAK3 | Janus kinase 3 | c.2164G>A | p.Val722Ile | 42.5 | neutral | COSM34213 |

| S9 (+) | TP53 | tumor protein P53 | c.-28-4G>A | - | 4.5 | no data available | - |

| M1 (+) | BRAF | serine/threonine kinase BRAF | c.1799_1800delinsAA | p.Val600Glu | 40 | pathogenic | COSM475 |

| PIK3CA | phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate 3-kinase | c.1031T>C | p.Val344Ala | 13.4 | pathogenic | COSM86951 | |

| STK11 | serine/threonine kinase 11 | c.1211C>T | p.Ser404Phe | 35.1 | no data available | - | |

| M2 (+) | BRAF | serine/threonine kinase BRAF | c.1799T>A | p.Val600Glu | 22.2 | pathogenic | COSM476 |

| CDKN2A | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A | c.169dup | p.Ala57GlyfsTer63 | 20.6 | pathogenic | COSM110662 | |

| SMAD4 | mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 | c.122A>G | p.Glu41Gly | 5.7 | no data available | - | |

| M3 (+) | BRAF | serine/threonine kinase BRAF | c.1799T>A | p.Val600Glu | 15.4 | pathogenic | COSM476 |

| APC | adenomatous polyposis coli | c.3949G>C | p.Glu1317Gln | 50 | pathogenic | COSM19099 | |

A RB1 gene variant was identified in case 1 (c.2033A>T; p.(His678Leu), VAF: 48%), while TP53 aberration was detected in case 3 (c.832C>T; p.(Pro278Ser), VAF: 92.4) and in case 9 (c.-28-4G>A, VAF: 5.5%) correlation with p53 IHC positivity was detected. Additional pathogenic variants were determined in case 3 (FBXW7, c.1031C>T; p.(Ser344Phe), VAF: 89.3%), in case 4 (CTNNB1, c.59C>T; p.(Ala20Val), VAF: 9%), and in case 6 (HNF1A, c.864del; p.(Pro291GlnfsTer51), VAF: 7.5%), and a benign STK11 (c.1062C>G; p.(Phe354Leu), VAF: 54.55%) variant was detected in case 2, a CDKN2A (c.442G>A; p.(Ala148Thr), VAF: 50%) variant was detected in case 5, and a JAK3 (c.2164G>A, p.(Val722Ile), VAF: 42.5%) variant was detected in case 8 was detected as well. In case 6 an ABL1 (c.740A>G; p.(Lys247Arg), VAF: 42.1%) and a FOXL2 (c.536C>G; p.(Ala179Gly), VAF: 65.3%) neutral aberration was identified. In MCPyV-negative case 7 no mutation was found.

Retrospectively, three MCPyV and BRAF-positive melanoma samples were analyzed using NGS (the fourth sample was not enough for NGS). Besides BRAF mutations (VAF: 40, 22.2, and 15.4%, respectively), the following aberrations were found: PIK3CA c.1031T>C, p.(Val344Ala, 13.4%) and STK11 c.1211C>T, and p.(Ser404Phe, 35.1%) in M1 melanoma case, CDKN2A c.169dup; p.(Ala57GlyfsTer63, 20.6%) and SMAD4 c.122A>G, p.(Glu41Gly, 5.7%) in M2; and, finally, APC c.3949G>C; p.(Glu1317Gln, 50%) in M3 sample (Table 3).

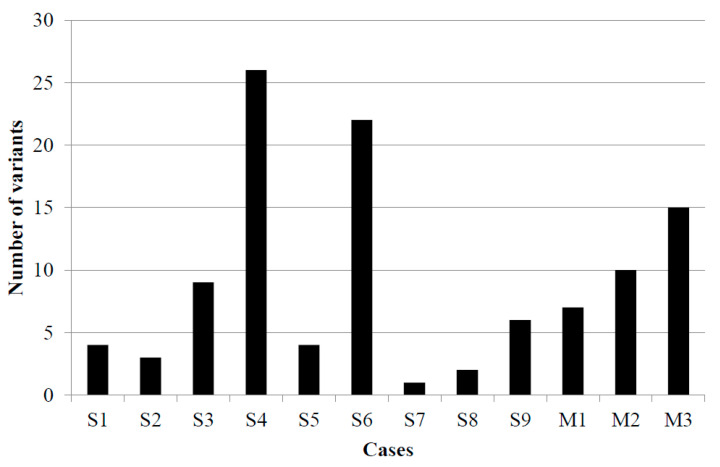

Variant tumor burden (VTB) was defined with the number of gene variants above 2% VAF (Figure 3). The largest VTB was in cases 4 and 6, while the smallest was in cases 7 and 8. Besides the MCPyV-associated case 7, in the other virus-negative case, case 5, low VTB was determined. In virus-associated melanoma cases, the average tumor burden was detected.

Figure 3.

Variant tumor burden in nine Merkel cell carcinoma and three malignant melanoma cases. S1–S9: Merkel cell carcinoma samples, M1–M3: melanoma samples.

4. Discussion

In our study, we compared two methods to detect MCPyV in MCC and melanoma samples. The MCPyV monoclonal antibody, targeting the large T-antigen (clone CM2B4), effectiveness ranged from 39% to 90% [6]. The sensitivity of IHC is also related to the preanalytic varying parameters such as tissue fixation as well as viral copy numbers in the tumor cells [16]. Studies comparing PCR to IHC detection of MCPyV usually demonstrate proper concordance. Based on our results, together with other studies, we found PCR to be more sensitive than IHC [17,18,19,20]. Furthermore, we used only PCR to identify MCPyV-associated melanoma samples.

MCPyV-positive tumors have favored overall survival compared to MCPyV-negative MCCs, which also showed aggressive molecular mechanisms [8]. After viral integration, MCPyV stimulates host cell gene mutations and consequently dysregulated cell proliferation. Advances in NGS techniques have enabled the identification of these mutational landscapes that clarify the significant differences between virus-positive and virus-negative cases. As in melanoma and other skin cancers that are associated with UV radiation, these mutations (namely C-to-T pyrimidine dimers) suggest that, at least in MCV-negative tumors, the cell is unable to effectively repair UV-induced damage and subsequently accumulates further mutations.

Studies of molecular profiling on MCCs are scant and even controversial. Increased expression of the KIT receptor tyrosine kinase, in primary MCCs, demonstrated a shorter survival compared to patients with reduced levels of KIT in the malignant cells, although activating mutations in KIT have not been identified in MCCs [9,21]. Other genetic aberrations were also described, such as activating PIK3CA mutations [10], expression of the Hedgehog signaling cascade [11], aberrations of growth factors, and cell proliferation regulation [22,23]. The large T antigen regulates the life cycle of the virus and the cell cycle of the host cells. The latter is caused by interaction with the tumor suppressor gene RB1 and TP53 genes. The small T antigen is capable of stimulating cell proliferation through activation of several signal transduction pathways [24]. Additionally, in MCC tumor cells, small T antigen binds SCF(Fbw7) protein, thereby stabilizing large T antigen, which is a substrate for this E3 ubiquitin ligase [25]. In our study, we identified genetic variants that affected the abovementioned RB1, TP53, and FBXW7 genes only in virus-positive MCC samples. Additional pathogenic variants were identified in CTNNB1 and HNF1A genes. In one study, the HNF1A gene mutation involvement of the virus-positive MCC pathogenesis was identified as well and, similar to our investigation, FGFR1, ABL1, and JAK3 variants were also demonstrated [26]. Aberrations involving EGFR, FOXL2, and STK11 genes in MCPyV-positive MCCs had not been identified earlier.

In the literature, significant differences in the mutational burden that exists between MCPyV-positive and -negative cases were characterized, an order of magnitude higher for somatic single nucleotide variants per exome in virus-negative tumors compared to virus-positive cases [13]. Another study compared the molecular genetics of MCPyV-positive and -negative tumors and identified that MCPyV-positive MCCs harbor relatively few mutations and do not display a definitive UV-signature, verifying the oncogenic role of T-antigens as dominant drivers for these tumors [27]. One large genomics study in MCC characterized the molecular landscape of immune checkpoint inhibitor response. MCPyV sequences were detected only in low tumor burden cases. The response rate was 50% in high VTB and 41% in low VTB and MCPyV-positive tumors [28]. On the contrary, due to the limited number of MCPyV-negative cases tested, VTB was higher in MCPyV-positive samples in our study.

We found four BRAF-mutant MCPyV-associated melanoma cases in our study subjects, which was discordant with earlier findings, where no virus-positive melanoma cases were found and, thus, the mutation status was not analyzed [29]. In small-cell lung cancer, cancer sharing differentiation markers with MCC and MCPyV was detected in 39% [30]. Additionally, MCPyV was present in Kaposi sarcoma [31], non-melanoma skin cancers [32,33], and other cancers [34].

Several studies dealt with genetic aberrations in melanoma using NGS [35,36,37], and, according to them, the most affected genes are BRAF, NRAS, and KIT. In our study, in the three virus-associated cases, besides BRAF mutation, PIK3CA, CDKN2A, and APC pathogenic variants were identified. Considering the genetic similarity between virus-associated MCC and MCPyV-positive melanoma samples, no significant differentiation was observed in the tumor burden, but the affected genes were different, owing to the randomly confused signal transduction pathways by the virus.

In conclusion, MCC is an aggressive cutaneous tumor that, although rare, is increasing in incidence. We used different methodologies to analyze the samples that could provide important information for potential therapeutic options and diagnostic approaches in the future. In MCPyV-positive MCC, RB1, TP53, FBXW7, CTNNB1, and HNF1A pathogenic variants were identified, while in virus-negative cases only benign variants were found. In contrast to studies found in the literature, a higher tumor burden was detected in virus-associated MCC compared to MCPyV-negative cases. No association was identified between virus infection and tumor burden in melanoma samples. We concluded that analyzing the key morphologic and immunohistological features of MCC is critical to avoid confusion with other cutaneous malignancies. Molecular genetic investigations such as NGS enable molecular stratification, which may have future clinical impact.

Author Contributions

A.M.: conceptualization, methodology, visualization; writing—original draft preparation; G.M.: supervision, funding acquisition; S.L.C.: methodology, visualization; S.K.: data curation, sample contribution; Y.-C.C.C.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, writing—review and editing, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Debrecen (protocol code 60355/2016/EKU, November 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to protecting the rights of patients.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Harms K.L., Healy M.A., Nghiem P., Sober A.J., Johnson T.M., Bichakjian C.K., Wong S.L. Analysis of Prognostic Factors from 9387 Merkel Cell Carcinoma Cases Forms the Basis for the New 8th Edition AJCC Staging System. Ann. Surg Oncol. 2016;23:3564–3571. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5266-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harms P.W. Update on Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Lab. Med. 2017;37:485–501. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coggshall K., Tello T.L., North J.P., Yu S.S. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: An Update and Review: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Staging. J. Am. Acad Derm. 2018;78:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agelli M., Clegg L.X., Becker J.C., Rollison D.E. The Etiology and Epidemiology of Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Curr. Probl. Cancer. 2010;34:14–37. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgerald T.L., Dennis S., Kachare S.D., Vohra N.A., Wong J.H., Zervos E.E. Dramatic Increase in the Incidence and Mortality from Merkel Cell Carcinoma in the United States. Am. Surg. 2015;81:802–806. doi: 10.1177/000313481508100819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tetzlaff M.T., Harms P.W. Danger Is Only Skin Deep: Aggressive Epidermal Carcinomas. An Overview of the Diagnosis, Demographics, Molecular-Genetics, Staging, Prognostic Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Advances in Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2020;33:42–55. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng H., Shuda M., Chang Y., Moore P.S. Clonal Integration of a Polyomavirus in Human Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moshiri A.S., Doumani R., Yelistratova L., Blom A., Lachance K., Shinohara M.M., Delaney M., Chang O., McArdle S., Thomas H., et al. Polyomavirus-Negative Merkel Cell Carcinoma: A More Aggressive Subtype Based on Analysis of 282 Cases Using Multimodal Tumor Virus Detection. J. Investig. Derm. 2017;137:819–827. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andea A.A., Patel R., Ponnazhagan S., Kumar S., DeVilliers P., Jhala D., Eltoum I.E., Siegal G.P. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Correlation of KIT Expression with Survival and Evaluation of KIT Gene Mutational Status. Hum. Pathol. 2010;41:1405–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nardi V., Song Y., Santamaria-Barria J.A., Cosper A.K., Lam Q., Faber A.C., Boland G.M., Yeap B.Y., Bergethon K., Scialabba V.L., et al. Activation of PI3K Signaling in Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:1227–1236. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuromi T., Matsushita M., Iwasaki T., Nonaka D., Kuwamoto S., Nagata K., Kato M., Akizuki G., Kitamura Y., Hayashi K. Association of Expression of the Hedgehog Signal with Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Infection and Prognosis of Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 2017;69:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong S.Q., Waldeck K., Vergara I.A., Schröder J., Madore J., Wilmott J.S., Colebatch A.J., De Paoli-Iseppi R., Li J., Lupat R., et al. UV-Associated Mutations Underlie the Etiology of MCV-Negative Merkel Cell Carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2015;75:5228–5234. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goh G., Walradt T., Markarov V., Blom A., Riaz N., Doumani R., Stafstrom K., Moshiri A., Yelistratova L., Levinsohn J., et al. Mutational Landscape of MCPyV-Positive and MCPyV-Negative Merkel Cell Carcinomas with Implications for Immunotherapy. Oncotarget. 2016;7:3403–3415. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harms P.W., Harms K.L., Moore P.S., DeCaprio J.A., Nghiem P., Wong M.K.K., Brownell I., International Workshop on Merkel Cell Carcinoma Research (IWMCC) Working Group The Biology and Treatment of Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Current Understanding and Research Priorities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018;15:763–776. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0103-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varga E., Kiss M., Szabó K., Kemény L. Detection of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus DNA in Merkel Cell Carcinomas. Br. J. Derm. 2009;161:930–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sirikanjanapong S., Melamed J., Patel R.R. Intraepidermal and Dermal Merkel Cell Carcinoma with Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Situ: A Case Report with Review of Literature. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2010;37:881–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuda M., Arora R., Kwun H.J., Feng H., Sarid R., Fernández-Figueras M.-T., Tolstov Y., Gjoerup O., Mansukhani M.M., Swerdlow S.H., et al. Human Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Infection I. MCV T Antigen Expression in Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Lymphoid Tissues and Lymphoid Tumors. Int. J. Cancer. 2009;125:1243–1249. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung H.S., Choi Y.-L., Choi J.-S., Roh J.H., Pyon J.K., Woo K.-J., Lee E.H., Jang K.-T., Han J., Park C.-S., et al. Detection of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus in Merkel Cell Carcinomas and Small Cell Carcinomas by PCR and Immunohistochemistry. Histol. Histopathol. 2011;26:1231–1241. doi: 10.14670/HH-26.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leitz M., Stieler K., Grundhoff A., Moll I., Brandner J.M., Fischer N. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Detection in Merkel Cell Cancer Tumors in Northern Germany Using PCR and Protein Expression. J. Med. Virol. 2014;86:1813–1819. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leroux-Kozal V., Lévêque N., Brodard V., Lesage C., Dudez O., Makeieff M., Kanagaratnam L., Diebold M.-D. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Histopathologic and Prognostic Features According to the Immunohistochemical Expression of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Large T Antigen Correlated with Viral Load. Hum. Pathol. 2015;46:443–453. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swick B.L., Srikantha R., Messingham K.N. Specific Analysis of KIT and PDGFR-Alpha Expression and Mutational Status in Merkel Cell Carcinoma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2013;40:623–630. doi: 10.1111/cup.12160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernández-Figueras M.T., Puig L., Musulen E., Gilaberte M., Ferrándiz C., Lerma E., Ariza A. Prognostic Significance of P27Kip1, P45Skp2 and Ki67 Expression Profiles in Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Extracutaneous Small Cell Carcinoma, and Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Histopathology. 2005;46:614–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henderson S.A., Tetzlaff M.T., Pattanaprichakul P., Fox P., Torres-Cabala C.A., Bassett R.L., Prieto V.G., Richards H.W., Curry J.L. Detection of Mitotic Figures and G2+ Tumor Nuclei with Histone Markers Correlates with Worse Overall Survival in Patients with Merkel Cell Carcinoma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2014;41:846–852. doi: 10.1111/cup.12383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook D.L., Frieling G.W. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: A Review and Update on Current Concepts. Diagn. Histopathol. 2016;22:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.mpdhp.2016.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwun H.J., Shuda M., Feng H., Camacho C.J., Moore P.S., Chang Y. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Small T Antigen Controls Viral Replication and Oncoprotein Expression by Targeting the Cellular Ubiquitin Ligase SCFFbw7. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harms K.L., Lazo de la Vega L., Hovelson D.H., Rahrig S., Cani A.K., Liu C.-J., Fullen D.R., Wang M., Andea A.A., Bichakjian C.K., et al. Molecular Profiling of Multiple Primary Merkel Cell Carcinoma to Distinguish Genetically Distinct Tumors From Clonally Related Metastases. JAMA Derm. 2017;153:505–512. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schrama D., Peitsch W.K., Zapatka M., Kneitz H., Houben R., Eib S., Haferkamp S., Moore P.S., Shuda M., Thompson J.F., et al. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Status Is Not Associated with Clinical Course of Merkel Cell Carcinoma. J. Investig. Derm. 2011;131:1631–1638. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knepper T.C., Montesion M., Russell J.S., Sokol E.S., Frampton G.M., Miller V.A., Albacker L.A., McLeod H.L., Eroglu Z., Khushalani N.I., et al. The Genomic Landscape of Merkel Cell Carcinoma and Clinicogenomic Biomarkers of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:5961–5971. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koburger I., Meckbach D., Metzler G., Fauser U., Garbe C., Bauer J. Absence of Merkel Cell Polyoma Virus in Cutaneous Melanoma. Exp. Derm. 2011;20:78–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Helmbold P., Lahtz C., Herpel E., Schnabel P.A., Dammann R.H. Frequent Hypermethylation of RASSF1A Tumour Suppressor Gene Promoter and Presence of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2009;45:2207–2211. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katano H., Ito H., Suzuki Y., Nakamura T., Sato Y., Tsuji T., Matsuo K., Nakagawa H., Sata T. Detection of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus in Merkel Cell Carcinoma and Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J. Med. Virol. 2009;81:1951–1958. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dworkin A.M., Tseng S.Y., Allain D.C., Iwenofu O.H., Peters S.B., Toland A.E. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Immunocompetent Individuals. J. Investig. Derm. 2009;129:2868–2874. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kassem A., Technau K., Kurz A.K., Pantulu D., Löning M., Kayser G., Stickeler E., Weyers W., Diaz C., Werner M., et al. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Sequences Are Frequently Detected in Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer of Immunosuppressed Patients. Int. J. Cancer. 2009;125:356–361. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Csoboz B., Rasheed K., Sveinbjørnsson B., Moens U. Merkel Cell Polyomavirus and Non-Merkel Cell Carcinomas: Guilty or Circumstantial Evidence? APMIS. 2020;128:104–120. doi: 10.1111/apm.13019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reiman A., Kikuchi H., Scocchia D., Smith P., Tsang Y.W., Snead D., Cree I.A. Validation of an NGS Mutation Detection Panel for Melanoma. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:150. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3149-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu M.-L., Zhou L., Sadri N. Comparison of Targeted next Generation Sequencing (NGS) versus Isolated BRAF V600E Analysis in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. Virchows Arch. 2018;473:371–377. doi: 10.1007/s00428-018-2393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mancini I., Simi L., Salvianti F., Castiglione F., Sonnati G., Pinzani P. Analytical Evaluation of an NGS Testing Method for Routine Molecular Diagnostics on Melanoma Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Tumor-Derived DNA. Diagnostics. 2019;9:117. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics9030117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to protecting the rights of patients.