Abstract

Ground beetles are natural predators of insect pests and small seeds in agroecosystems. In semiarid cropping systems of the Northern Great Plains, there is a lack of knowledge to how ground beetles are affected by diversified cover crop rotations. In a 2-yr study (2018 and 2019), our experiment was a restricted-randomization strip-plot design, comprising summer fallow, an early-season cover crop mixture (five species), and a mid-season cover crop mixture (seven species), with three cover crop termination methods (i.e., herbicide, grazing, and haying). Using pitfall traps, we sampled ground beetles in five 48-h intervals throughout the growing season (n = 135 per year) using growing degree day (GDD) accumulations to better understand changes to ground beetle communities. Data analysis included the use of linear mixed-effects models, perMANOVA, and non-metric multidimensional scaling ordinations. We did not observe differences among cover crop termination methods; however, activity density in the early-season cover crop mixture decreased and in summer fallow increased throughout the growing season, whereas the mid-season cover crop mixture peaked in the middle of the summer. Ground beetle richness and evenness showed a nonlinear tendency, peaking in the middle of the growing season, with marginal differences between cover crops or fallow after the termination events. Also, differences in ground beetle composition were greatest in the early- and mid-season cover crop mixtures earlier in the growing season. Our study supports the use of cover crop mixtures to enhance ground beetle communities, with potential implications for pest management in dryland cropping systems.

Keywords: cover crop mixture, generalist predator, growing degree day, cover crop termination

Large-scale intensive crop production is most often achieved through heavy reliance on energy-dependent practices to control for pest populations, maintain soil fertility, and prepare fields for a cash crop. Although this approach may manage for optimal crop yield, it has been faulted for its lack of sustainability, including declines in biodiversity, soil erosion, accumulation of pest populations, greenhouse gas emissions, and eutrophication (Tilman et al. 2011, Robertson 2015, Scheelbeek et al. 2018). Recently, the reduction of excessive off-farm inputs and the development of ecologically based cropping practices has gained interest for improving sustainability of crop ecosystems that produce food, fiber, and bioenergy, while addressing multiple socioeconomic and environmental conflicts (Anderson et al. 2019).

Cover cropping is a well-known strategy to incorporate ecologically based management practices into agroecosystems as it can help prevent erosion, increase soil organic matter, improve soil nutrient retention, and suppress weed populations (Derksen et al. 2002, Snapp et al. 2005, Blanco-Canqui et al. 2013). In addition, cover cropping can enhance ecosystem services by providing food and habitat to beneficial organisms and fuel nutrient cycling (Sheaffer and Seguin 2003, Jian et al. 2020). However, cover crops do not provide direct income to farmers and come with the added expenses of establishment, termination, and pest management. Also, in areas with compromised moisture availability, cover crops require termination before they lower soil water content and produce seeds to reduce impacts on the subsequent cash crop (Miller et al. 2011, O’Dea et al. 2013). One common method of terminating cover crops is the use of herbicides, a practice that can impose selection pressure for herbicide resistance on weeds (Baucom 2019) and unintentionally impact beneficial insect populations (Egan et al. 2014, Keren et al. 2015). Integrative approaches for cover crop termination, like livestock-grazing and haying, may be economically and ecologically sustainable by providing an alternative revenue source to farmers (i.e., feed for livestock) and enhance the provisioning of ecosystem services (Thiessen Martens and Entz 2011, McKenzie et al. 2016).

Cover crop characteristics, such as species phenology and morphology, and their termination methods act as community assembly factors that can select for some taxa that contribute to beneficial biodiversity, like ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) (McKenzie et al. 2017, Adhikari and Menalled 2020). Ground beetles are one of the most diverse, common, and abundant groups of insects, and they help suppress crop pests by preying on other insects such as aphids, fly maggots, grubs, slugs, and other beetles (Sunderland 1975), whereas members of some tribes—Harplini and Zabrini—prey on small seeds, which can help manage certain weed populations (Honek et al. 2003, Gaines and Gratton 2010). Therefore, by altering the abundance diversity of ground beetles, cover crops can improve the biological control of insect pests and weed populations (Kromp 1999).

Cropping systems in the semiarid regions of Northern Great Plains are dominated by wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), often grown in rotation with summer fallow, a year-long interval where no crops are grown to conserve soil moisture and also facilitate the use of herbicides (Peterson et al. 1996, Tanaka et al. 2010). The integration of multiple species cover crop mixtures has recently gained interest in the Northern Great Plains as an approach to increase total cover crop biomass and suppress weed populations (Smith et al. 2015, Mesbah et al. 2019, USDA, NRCS 2020). There is limited knowledge in this region regarding the impacts of cover crop mixtures and termination methods on ground beetle communities, but see McKenzie et al. (2016). However, previous research conducted in other regions have found that cover crops and cropping system can impact ground beetle communities (Carmona and Landis 1999, Depalo et al. 2020). Hence, we conducted a 2-yr experiment to assess the impact of the presence and species composition of cover crop mixtures (i.e., fallow vs two cover crop mixtures with different species composition), and cover crop termination methods (herbicide, cattle-grazing, and haying) on the abundance and diversity of ground beetle communities in a conventional farming system. We hypothesized that 1) in comparison with fallow fields, cover crops will enhance ground beetle activity density and diversity, and 2) ground beetle communities will shift as function of cover crop composition and terminations method.

Materials and Methods

Study Site and Cropping System

We conducted a 2-yr experiment in State University 2018 and 2019 at the Montana Northern Agricultural Research Center, located southwest of Havre, MT (48°29′48.8″N, 109°48′10.4″W). The study site receives an average annual precipitation of 305 mm, and the average high and low temperatures are 13.6 and 0.0°C, respectively (Western Regional Climate Center 2020). The soil at the study site is classified as a mix of Joplin and Telstad clay loam (Soil Survey Staff, NRCS, 2018).

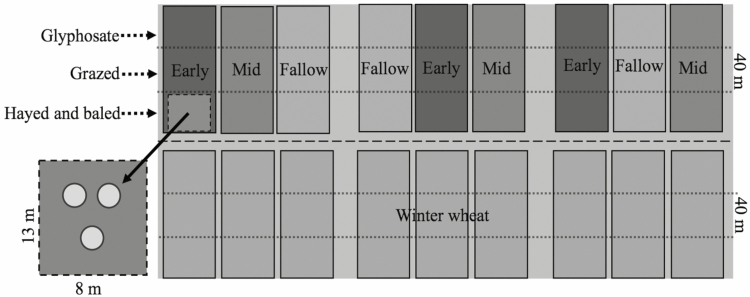

The experiment was established as two replicated field trials occurring in separate years, designed as a restricted-randomization strip-plot design with three repetitions each (Fig. 1). The two plot trials followed alternate rotations with the winter wheat and fallow/cover crop phases present each year at the studied site. In the fallow/cover crop phase, treatments comprised a summer fallow, an early-season cover crop mixture (five species), which was planted in early spring, and a mid-season cover crop mixture (seven species) which was planted approximately 2 wk later. The location of each treatment was randomized in the first year of the study (2012–2013) to 8 × 44 m plots and maintained through time. Cover crop mixture and fallow plots were assigned to three different termination and weed management methods (herbicide, grazing, and haying and baling), which were applied in a strip-plot design (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Experimental design representing the fallow/cover crop phase (top), where a summer fallow, an early-season cover crop mixture, or a mid-season cover crop mixture were established (top), and the winter wheat phase (bottom). Three alternative methods were used to terminate cover crops (top). Three pitfall traps (circles) were placed within each 8 × 13 m strip plot of the fallow/cover crop phase of each year and were homogenized after each 48-h sample period (n = 27 traps/sample period).

Summer Fallow and Cover Crop Mixtures

The fallow/cover crop phase consisted of summer fallow, an early-season cover crop mixture, and a mid-season cover crop mixture. Phases of summer fallow began after winter wheat harvest on 12 July 2017 and 26 July 2018 and ended on 21 September 2018 and 13 September 2019. Before cover crop mixtures were planted, the summer fallow and cover crop treatment plots were sprayed with 2,240 g/ha of ai glyphosate. Summer fallow plots were also treated with 1120 g of ai glyphosate plus 340 g/ha of ai dicamba on an ‘as-needed’ basis throughout the growing season to manage for weed populations. Cover crop mixtures included a variety of cover crop species known to provide benefits (i.e., erosion control and nitrogen fixation) to agricultural soils in the studied region. The early-season mixture had five species: radish (Raphanus raphanistrum L.), field pea (Pisum sativum L.), oat (Avena sativa L.), turnip (Brassica rapa L.), and hairy vetch (Vicia villosa Roth). The mid-season mixture had seven species: oat, radish, field pea, turnip, lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus), and sorghum sudan grass (Sorghum × drummondii Nees ex. Steud.). In the 2019 season, a similar mid-season mixture was sowed in place of our original mid-season cover crop mixture containing oat, chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), radish, turnip, soybean, hairy vetch, and millet (Setaria italica L.) Each year, cover crop planting dates varied based on local weather conditions. The early-season mixture was planted on 4 May 2018 and 29 April 2019. The mid-season mixture was planted on 14 May 2018 and 9 May 2019. All cover crop species were seeded at depth of 2.54 cm at different seeding rates (Supp Table 1 [online only]) using a 3.7-m Conservapack no-till disk planter. At planting, cover crops were fertilized with a 20-20-20 dosage of N-P-K at 112 kg/ha.

Termination of Cover Crops

Cover crop mixtures were terminated before the anthesis of oat to preserve soil moisture for the subsequent crop with either herbicide (glyphosate, applied at 2,500 g ai per hectare), haying and baling, or cattle grazing. The herbicide application and haying treatments occurred on 9 July 2018 and 8 July 2019. In the haying and baling treatment, cover crops were mechanically cut and bales were removed from the field. The cattle grazed treatment used 8–10 bulls fenced in the 12 × 360 m termination strip plots from 11 to 13 July 2018 and from 9 to 11 July 2019. In addition, 2,000 g of ai glyphosate per hectare plus 340 g of ai dicamba per hectare was applied to terminate any regrowth of cover crops and weeds in the grazed and hayed termination treatments approximately 4 wk after the initial termination because haying and grazing did not sufficiently kill the cover crops.

Ground Beetle Community Sampling

To assess differences in ground beetles activity density and diversity through time, pitfall traps were set up in the fallow/cover crop phase within each termination strip-plot and opened for a 48-h interval for five different sample intervals each year (Fig. 1; n = 3 per treatment/sample interval/year). Specifically, sample intervals started on 22 May, 12 June, 30 June, 23 July, and 14 August 2018 and on 30 May, 13 June, 1 July, 15 July, and 13 August 2019. Three 10 × 12 cm holes were dug in a triangular pattern approximately 2–3 m apart using a post hole auger where a double stacked cup (Solo Cup Co., Lake Forest, IL) was placed, then adjusted to be flush to the ground surface, and filled with approximately one-third full of propylene glycol-based antifreeze (Arctic Ban Antifreeze, Camco Manufacturing, Greensboro, NC). After each 48-h interval, the three pitfall traps were homogenized, transferred to plastic plot-specific bags (Whirl-Pak, Nasco Inc., Fort Atkinson, WI), and stored in the freezer until processing. Ground beetles were cleaned, sorted, and placed in 70% ethanol for preservation and later identified to species following Lindroth (1969). To better account for the impacts of cropping systems on ground beetle communities each year, we calculated growing degree days (GDD) from 1 January 2018 and 2019 to the last sample interval on 14 August 2018 and 13 August 2019, using 0°C base temperature for wheat (Miller et al. 2001).

Statistical Analysis

Metrics for ground beetle communities included abundance (activity density), species richness, evenness, and species composition. We calculated species richness as the total number of species present per 8 × 13 m strip plot per sample interval each year, and species evenness was calculated using the Shannon–Wiener diversity index (Fisher et al. 1943) using the ‘diversity’ function in the ‘vegan’ package (Oksanen et al. 2019). To assess the effects of the presence (i.e., fallow and cover crop) and composition (i.e., early-season and mid-season) of cover crops, termination (i.e., herbicide, grazed, hayed), sample interval (GDD °C), and year on ground beetle activity density, richness, and evenness, we fit a linear mixed-effects model using the ‘lmer’ function in the ‘lme4’ package (Bates et al. 2020). For all response variables, we used a step down P-value model selection approach, starting with a four-way interaction between the fixed effects. Marginal F-tests were performed to determine the need for interactions in the models. A quadratic term was applied to sample interval to account for parabolic peaks of response variables. For ground beetle species richness, a Poisson distribution was initially considered; however, during model comparison and modeling fitting, the normal or Gaussian distribution better characterized the data. The presence and composition of cover crops, termination, sample interval, and year and their interactions were treated as fixed effects and plot, block, year, and sample interval were treated as random effects. Assumptions of normality and constant variance were assessed visually using diagnostic plots. We used F-test derived from Type III ANOVA tests using the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova et al., 2017) and the ‘emmeans’ package to assess post hoc pairwise comparison when factors accounted for variation in ground beetle activity density and richness. We produced graphics for ground beetle activity density in the package ‘ggplot 2’ (Wickham 2016).

To assess changes in ground beetle assemblages based on activity density, we calculated dissimilarity among strip plots with the Bray–Curtis index in the ‘vegdist’ function in the ‘vegan’ package. We evaluated whether there were differences in ground beetle communities among treatments (presence and composition of a cover crop, and termination), sample interval, and year using permutational multivariate analysis of variance (perMANOVA) algorithm ‘adonis’ in the ‘vegan’ package. To visualize differences in ground beetle composition, we used a non-metric multidimensional scaling analysis of each strip plot. The analysis was conducted using the ‘metaMDS’ algorithm also in the ‘vegan’ package. Data were analyzed in the statistical analysis program R (R Development Core Team).

Results

We collected a total of 2,319 specimens over the course of our 2-yr study, representing 28 species, of which 14 occurred in the fallow treatments, 24 occurred in the early-season mixture, and 18 occurred in the mid-season mixture (Supp Table 2 [online only]). Of the 28 species, three specimens that could not be identified confidently to species were sampled at very low frequency (Supp Table 2 [online only]). The five most abundant species in the fallow treatment were Harpalobrachys leiroides (n = 206; 31% of beetles observed in fallow treatments in both years), Poecilus scitulus (n = 164; 24%), Harpalus amputatus (n = 105; 16%), Cratacanthus dubius (n = 88; 13%), and Cicindela punctulata (n = 42; 6%), representing about 90% of total capture. In the early-season cover crop mixture, the five most abundant species were P. scitulus (n = 630; 62% of all beetles captured in the early-season mixture), H. amputatus (n = 148; 15%), H. leiroides (n = 80; 8%), Apristus pugetanus (n = 32; 3%), and Amara littoralis (n = 26; 3%), representing about 91% of total capture. The five most abundant species in the mid-season cover crop mixture were P. scitulus (n = 347; 55% of all beetles captured in the mid-season mixture), H. leiroides (n = 108; 17%), H. amputates (n = 92; 13%), C. dubius (n = 23; 4%), and A. littoralis (n = 11; 2%), representing about 91% of total capture.

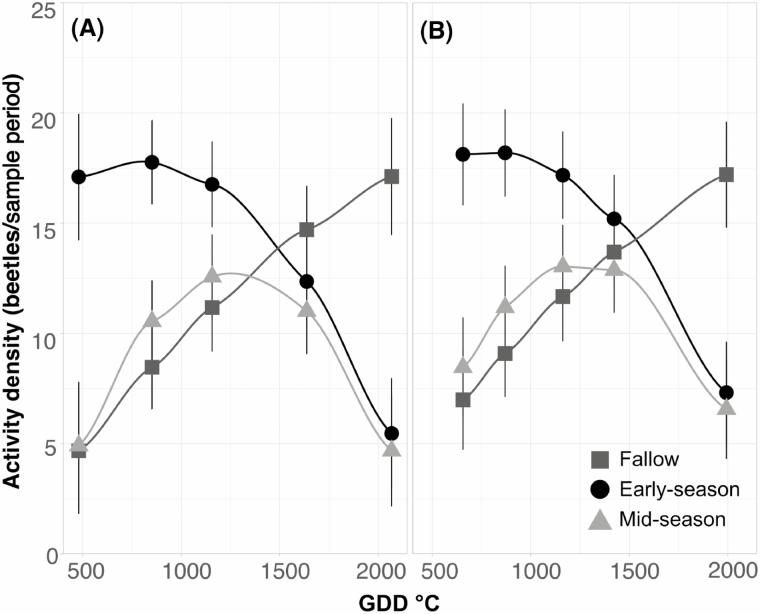

We observed differences in ground beetle activity density among sample intervals, but not among the presence and composition of cover crop, termination method, or year. However, there was an interaction between the presence and composition of cover crops and sample interval (Table 1). Mean activity density of ground beetles in the early-season cover crop mixture decreased with sample intervals in both years, where activity density was greatest during the 480–515 GDD °C and 852–882 GDD °C sample intervals of 2018, and the 646–678 GDD °C and 870–909 GDD °C sample intervals of 2019. Mean activity density in the fallow treatments increased with sample interval in both years, with activity density greatest in the 2,068–2,101 GDD °C and 1,993–2,026 GDD °C sample intervals of 2018 and 2019. In the mid-season cover crop mixture, mean activity density in both years peaked in the middle of the growing season (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Type III ANOVA tables for ground beetle activity density (A), richness (B), and perMANOVA for community composition (C) in response to the presence and composition of a cover crop (fallow/cover crop), sample interval (polynomial term; GDD C), year, termination, and their interactions, when significant

| (A)Ground beetle activity density | df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fallow/cover crop | 2, 5 | 3.31 | 0.125 |

| Sample interval | 2, 82 | 4.48 | 0.011 |

| Year | 1, 2 | 0.05 | 0.828 |

| Termination | 2, 204 | 1.44 | 0.239 |

| Fallow/cover crop × sample interval | 4, 45 | 6.54 | <0.001 |

| (B)Ground beetle species richness | df | F | p |

| Fallow/cover crop | 2, 37 | 2.46 | 0.099 |

| Sample interval | 2, 42 | 15.01 | <0.001 |

| Year | 1, 2 | 1.61 | 0.376 |

| Termination | 2, 37 | 0.55 | 0.578 |

| Fallow/cover crop × sample interval | 4, 133 | 2.03 | 0.094 |

| (C)Ground beetle species evenness | df | F | p |

| Fallow/cover crop | 2, 10 | 3.18 | 0.083 |

| Sample interval | 2, 45 | 13.71 | <0.001 |

| Year | 1, 2 | 1.06 | 0.395 |

| Termination | 2, 238 | 0.255 | 0.798 |

| (D)Ground beetle species composition | df | F | p |

| Fallow/cover crop | 2, 244 | 9.64 | <0.001 |

| Sample interval | 1, 244 | 15.46 | <0.001 |

| Year | 1, 244 | 4.56 | <0.003 |

| Termination | 2, 244 | 1.61 | 0.086 |

| Fallow/cover crop × sample interval | 2, 244 | 8.08 | <0.001 |

| Fallow/cover crop × year | 2, 244 | 1.75 | 0.081 |

| Sample interval × year | 1, 244 | 2.12 | 0.074 |

Bold values indicate significant differences between treatments at p < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Mean ground beetle activity density recorded in 2018 (A) and 2019 (B) among treatments with different presence and composition of cover crops (fallow, early-season, and mid-season cover crop mixtures), and sample intervals (growing degree days, GDD °C). Error bars indicate the SEM. Termination of cover crops occurred at approximately 1300 GDD °C each year.

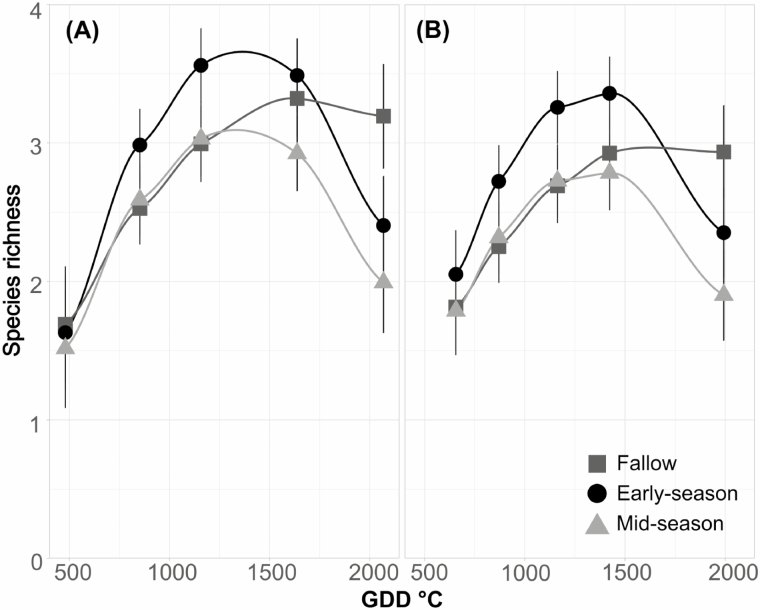

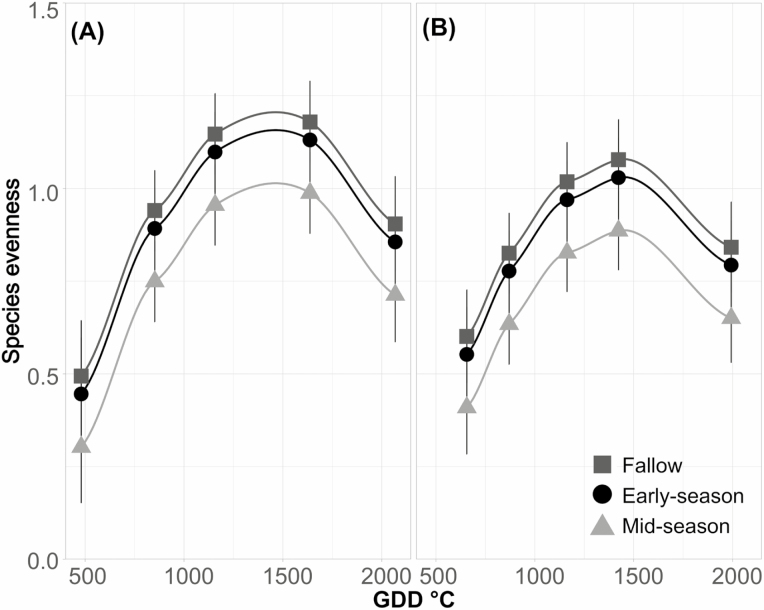

We did not detect differences in mean ground beetle species richness or evenness among termination method or year; however, we did observe marginal differences among the presence and composition of a cover crop and strong differences in sample intervals, with a marginal interaction (Table 1). Sample interval presented the strongest effect on richness and evenness, as these variables peaking in the middle of the growing season (Figs. 3 and 4). The effect of the presence and composition of a cover crop on ground beetle species richness and evenness was dependent on sample interval. For instance, mean species richness in the early-season cover crop mixture tended to be higher than the mid-season; however, both peaked in the middle of the growing season. Yet, mean species richness in the fallow treatments remained greater later in the growing season. Specifically, mean species richness was, on average, one species greater in the fallow treatments compared with the mid-season cover crop mixture at sample intervals 2,068–2,101 GDD °C and 1,993–2,026 GDD °C in 2018 and 2019 (Fig. 3). Similarly, species evenness showed marginal evidence of differences among the presence and composition of a cover crop and sample intervals. Species evenness peaked in the middle of the growing season for fallow and both cover crop mixtures; however, mean species evenness in fallow and the early-season cover crop mixture tended to be greater than the mid-season cover crop mixture. Specifically, the evenness metric was 0.19 greater in the fallow compared with the mid-season cover crop mixture at sample intervals 2,068–2,101 GDD °C and 1,993–2,026 GDD °C in 2018 and 2019 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Mean ground beetle species richness recorded in 2018 (A) and 2019 (B) among treatments with different presence and composition of a cover crop (fallow, early-season, and mid-season cover crop mixtures) and sample interval (growing degree days, GDD °C). Error bars indicate the SEM. Termination of cover crops occurred at approximately 1300 GDD °C each year.

Fig. 4.

Mean ground beetle species evenness recorded in 2018 (A) and 2019 (B) among treatments with different presence and composition of a cover crop (fallow, early-season, and mid-season cover crop mixtures) and sample interval (growing degree days, GDD °C). Error bars indicate the SEM. Termination of cover crops occurred at approximately 1300 GDD °C each year.

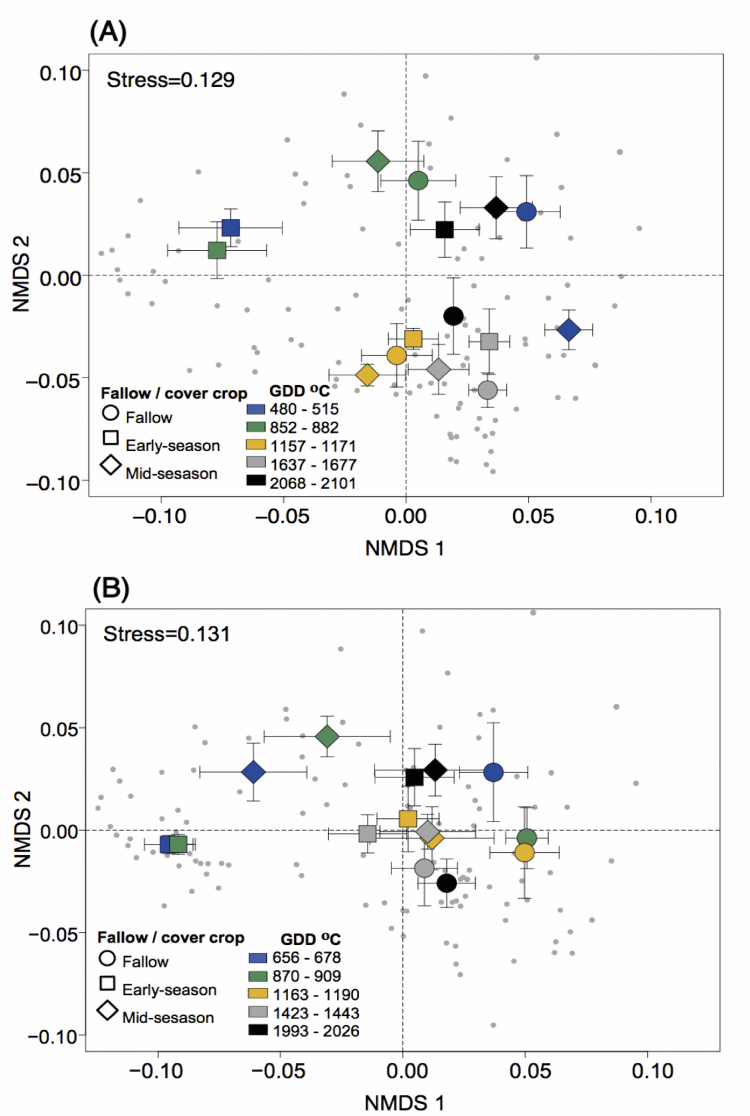

The perMANOVA results indicated differences in ground beetle community composition among the presence and composition of cover crops, sample interval, and year, but a marginal difference among termination methods. There was also a marginal interaction between both presence and composition of a cover crop and sample interval with year (Table 1; Fig. 5). We observed the largest differences in ground beetle composition in the early-season and mid-season cover crop mixtures during the 480–515 GDD °C and 852–882 GDD °C sample intervals of 2018, and the 646–678 GDD °C and 870–909 GDD °C sample intervals of 2019, which is likely due to the greater activity density of P. scitulus (Supp Table 2 [online only]). Among these later sample intervals, there was much overlap in ground beetle composition; however, we observed that many species were more abundant in specific fallow/cover crop phase treatments and sample intervals. For example, H. amputates, A. pungenatus, and A. littoralis all had greater activity density in the early-season cover crop mixture at different sample intervals between years (Supp Table 2 [online only]). In 2018, activity density of C. punculata was greatest in fallow treatments during the 2,068–2,101 GDD °C sample interval of 2018, but did not appear abundant in 2019. While in 2019, activity density of A. idahoana and C. dubis were greater in fallow treatments, particularly during the 1,993–2,026 GDD C sample interval.

Fig. 5.

Variation in ground beetle communities in 2018 (A) and 2019 (B) in response to the presence and composition of a cover crop and sample intervals. Error bars represent the SE of plots within the presence and composition of a cover crop using different shapes (fallow, early-season, and mid-season) and sample intervals using different colors (growing degree days, GDD °C). Termination of cover crops occurred at approximately 1300 GDD °C each year.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the impacts that the presence, composition, and termination methods of cover crops have on ground beetle communities in the semiarid section of the Northern Great Plains, an important small grain, pulse, and oilseed crop production region (Padbury et al. 2002). Our study indicated that the presence (i.e., fallow or cover crop) and composition (i.e., early- or mid-season) characteristics of cover crops affected ground beetle communities. Results also indicated that the termination method of cover crops (i.e., herbicide, cattle-grazing, and haying) does not differently affect ground beetle communities and that although beetle activity density was greatest in the early-season cover crop mixture, it peaked at the end of the summer in the fallow plots. Overall, this study highlights the potential of cover crop mixtures as an ecologically based management strategy to alter ground beetle communities early in the growing season, emphasizing the role of cover crop composition and planting date as a driver of ground beetle communities.

The studied cropping systems selected for a subset of common ground beetle species that occur in the Northern Hemisphere, including genera such as Harpalus, Amara, Pterostichus, and Agonum. However, we observed fewer genera than previous studies that occurred in organic farming systems (McKenzie et al. 2016, Adhikari and Menalled 2018), suggesting that conventional farming practices are strong drivers of ground beetle communities in this region. In agreement, Adhikari and Menalled (2020) observed that cover cropping favored ground beetle communities, with stronger patterns observed in organically managed farms, whether tilled or grazed, in comparison with chemically managed no-tillage systems. In the studied systems, the divergence in ground beetle communities suggests that the presence and composition of cover crops can act as ecological filters to ground beetle communities, favoring some taxa over others (Funk et al. 2008). However, the effect of the presence and composition of cover crops was specific to different sample intervals. Ground beetles have shown to be highly mobile organisms (Kennedy 1994), and the limited size of the studied plots may have masked the effects of our treatments on the ground beetle community. Specifically, we observed greater ground beetle activity density in the early-season cover crop mixture during sample intervals that occurred between 500 and 1,000 GDD°C, while, after termination of the cover crop mixtures, fallowed fields supported the greatest activity density.

Changes to the ground beetle community may have been influenced by the use of herbicide in our study. Previous research suggests that arthropod communities are sensitive to herbicides in agroecosystems (Egan et al. 2014) and, compared with the fallow treatments, it is possible that the ground beetle communities sampled in the cover crop mixtures were affected by the applications of herbicide that occurred before planting of cover crop and before the last sample interval to control the regrowth of cover crops and weeds. However, the early-season cover crop mixture, allowed for greater abundance of ground beetles compared with the mid-season and fallow treatments, indicating that early spring planted cover crops have the potential to provide ecological benefits in a conventional farming system.

Interestingly, the mid-season planted cover crop mixture had consistently less activity density, species richness, and species evenness throughout all sample intervals of both years, suggesting that an early-season cover crop mixture, planted approximately 2 wk prior, provided more favorable conditions for ground beetle communities. This observation may be in accordance with previous studies, which indicate that greater plant species richness does not guarantee greater arthropod abundance (Siemann et al. 1998, Haddad et al. 2001). More specifically, in our studied system, extending the planting date to incorporate more species of cover crops (the mid-season cover crop mixture) may not be the optimal method to improve ground beetle communities.

In accordance with previous studies conducted in this region (Goosey et al. 2015; Adhikari and Menalled 2018, 2020), cropping systems can favor specific taxa of ground beetles, while excluding others. However, the ecology of many of the ground beetle species sampled in this study is largely unknown. For example, although P. scitulus is associated with tall-grass prairies at the edges of sloughs and ponds (Lindroth 1969), in our study, activity density was particularly high in the early-spring sample intervals (500–1,000 GDD °C), primarily in the early-season cover crop mixture.

Ground beetles have broad diets (Sunderland 1975), and in addition to preying on insect pests, many species are known to consume the small seeds of certain weedy species (Frei et al. 2019, Carbonne et al. 2020), which increases the potential to regulate weed populations. In our study, we observed distinct changes in ground beetle community composition in the early-season cover crop mixture, which supported food and habitat for a particular subset of species. For example, activity density of species within the genera Amara and Harpalus—ground beetle species that are known to prey on weed seeds—was greater in the early-season cover crop mixture in the middle of the growing season, compared with summer fallow and the mid-season cover crop mixture. Because the mid-season cover crop mixture had greater cover crop species richness and was planted 2 wk later than the early-season cover crop mixture, the early-season mixture accumulated more total cover crop biomass (DuPre 2020). Thus, the selection of cover crop species to accommodate an early-spring planting may beneficially alter ground beetle communities, and therefore provide the potential to increase pest regulation within conventional dryland cropping systems.

Cover crops can provide ecosystem services such as soil erosion control, accumulation of soil organic matter, improved soil nutrient retention, and suppression of weed populations (Derksen et al. 2002, Snapp et al. 2005, Blanco-Canqui et al. 2013). Still, additional research on effects of cover crops on natural enemies and biological controls is needed in semiarid agroecosystems. Cover crop mixtures have potential to beneficially alter ground beetle communities, compared with cover crops planted in monocultures by incorporating multiple cover crop species characteristics (Carcamo and Spence 1994). Overall, our results show that the use of cover crop mixtures can play a beneficial role in supporting ground beetles in semiarid agroecosystems in the short term; however, more research is needed to study the factors that mediate their attraction in cover crop mixtures and how the long-term provision of pest regulation may vary among cover crop composition and summer fallow.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA; 2018-67013-27919). We thank the researchers and staff at the Montana State University Northern Agricultural Research Center for the providing the experimental site, support on the project, and other accommodations. We extend our gratitude to S. Adhikari for his help on beetle identification, and C. Dittemore, C. Larson, K. Koepsel, D. Chichinsky, J. Schafer, D. Alambarrio, and T. Leppicello for their contributions in the field and laboratory.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed experiment: FDM. Investigation: MED, FDM, DKW. Data Analysis: MED, TFS. Manuscript preparation and editing: MED, FDM, DKW.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References Cited

- Adhikari, S., and F. D. Menalled. . 2018. Impacts of dryland farm management systems on weeds and ground beetles (Carabidae) in the Northern Great Plains. Sustainability 10: 2146. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, S., and F. D. Menalled. . 2020. Supporting beneficial insects for agricultural austainability: the role of livestock-integrated organic and cover cropping to enhance ground beetle (Carabidae) communities. Agronomy 10: 1210. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C. R., J. Bruil, M. J. Chappell, C. Kiss, and M. P. Pimbert. . 2019. From transition to domains of transformation: getting to sustainable and just food systems through agroecology. Sustainability 11: 5272. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D., M. Maechler, B. Bolker aut, cre, S. Walker, R. H. B. Christensen, H. Singmann, B. Dai, F. Scheipl, G. Grothendieck, P. Green, and J. Fox. . 2020. lme4: linear mixed-effects models using “Eigen” and S4. Journal of Statistical Software. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom, R. S. 2019. Evolutionary and ecological insights from herbicide-resistant weeds: what have we learned about plant adaptation, and what is left to uncover? New Phytol. 223: 68–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Canqui, H., J. D. Holman, A. J. Schlegel, J. Tatarko, and T. M. Shaver. . 2013. Replacing fallow with cover crops in a semiarid soil: effects on soil properties. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 77: 1026–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonne, B., D. A. Bohan, and S. Petit. . 2020. Key carabid species drive spring weed seed predation of Viola arvensis. Biol. Control 141: 104–148. [Google Scholar]

- Carcamo, H. A., and J. R. Spence. . 1994. Crop type effects on the activity and distribution of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Environ. Entomol. 23: 684–692. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, D. M., and D. A. Landis. . 1999. Influence of refuge habitats and cover crops on seasonal activity-density of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) in field crops. Environ. Entomol. 28: 1145–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Depalo, L., G. Burgio, S. Magagnoli, D. Sommaggio, F. Montemurro, S. Canali, and A. Masetti. . 2020. Influence of cover crop termination on ground dwelling arthropods in organic vegetable systems. Insects 11: 445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derksen, D. A., R. L. Anderson, R. E. Blackshaw, and B. Maxwell. . 2002. Weed dynamics and management strategies for cropping systems in the northern Great Plains. Agron. J. 94: 174–185. [Google Scholar]

- DuPre, M. 2020. Impacts of cover crop mixtures and changes to temperature and soil moisture on crop productivity and weed communities in a dryland small-grain cropping system. M.S. thesis, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, J. F., E. Bohnenblust, S. Goslee, D. Mortensen, and J. Tooker. . 2014. Herbicide drift can affect plant and arthropod communities. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 185: 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R. A., A. S. Corbet, and C. B. Williams. . 1943. The relation between the number of species and the number of individuals in a random sample of an animal population. J. Anim. Ecol. 12: 42. [Google Scholar]

- Frei, B., Y. Guenay, D. A. Bohan, M. Traugott, and C. Wallinger. . 2019. Molecular analysis indicates high levels of carabid weed seed consumption in cereal fields across Central Europe. J. Pest Sci. 92: 935–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk, J. L., E. E. Cleland, K. N. Suding, and E. S. Zavaleta. . 2008. Restoration through reassembly: plant traits and invasion resistance. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23: 695–703.18951652 [Google Scholar]

- Gaines, H. R., and C. Gratton. . 2010. Seed predation increases with ground beetle diversity in a Wisconsin (USA) potato agroecosystem. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 137: 329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Goosey, H. B., S. C. McKenzie, M. G. Rolston, K. M. O’Neill, and F. D. Menalled. . 2015. Impacts of contrasting alfalfa production systems on the drivers of carabid beetle (Coleoptera: Carabidae) community dynamics. Environ. Entomol. 44: 1052–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, N. M., D. Tilman, J. Haarstad, M. Ritchie, and J. M. Knops. . 2001. Contrasting effects of plant richness and composition on insect communities: a field experiment. Am. Nat. 158: 17–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honek, A., Z. Martinkova, and V. Jarosik. . 2003. Ground beetles (Carabidae) as seed predators. Eur. J. Entomol. 100: 531–544. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, J., X. Du, M. S. Reiter, and R. D. Stewart. . 2020. A meta-analysis of global cropland soil carbon changes due to cover cropping. Soil Biol. Biochem. 143: 107735. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, P. J. 1994. The distribution and movement of ground beetles in relation to set-aside arable land, pp. 439–444. In K. Desender, M. Dufrêne, M. Loreau, M. L. Luff, and J.-P. Maelfait (eds.), Carabid beetles: ecology and evolution, series entomologica. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Keren, I. N., F. D. Menalled, D. K. Weaver, and J. F. Robison-Cox. . 2015. Interacting agricultural pests and their effect on crop yield: application of a Bayesian decision theory approach to the joint management of Bromus tectorum and Cephus cinctus. PLoS One 10: e0118111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromp, B. 1999. Carabid beetles in sustainable agriculture: a review on pest control efficacy, cultivation impacts and enhancement. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 74: 187–228. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova, A., P. B. Brockhoff, and R. H. B. Christensen. . 2017. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Soft. 82: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lindroth, C. H. 1969. The ground beetles (Carabidae, excl. Cicindelinae) of Canada and Alaska, Part 1–6. Opusc. Entomol. Entomologiska Siillskapet, Lund, Sweden. (http://www.librarything.com/work/10804214). [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, S. C., H. B. Goosey, K. M. O’Neill, and F. D. Menalled. . 2016. Impact of integrated sheep grazing for cover crop termination on weed and ground beetle (Coleoptera: Carabidae) communities. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 218: 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, S. C., H. B. Goosey, K. M. O’Neill, and F. D. Menalled. . 2017. Integration of sheep grazing for cover crop termination into market gardens: agronomic consequences of an ecologically based management strategy. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 32: 389–402. [Google Scholar]

- Mesbah, A., A. Nilahyane, B. Ghimire, L. Beck, and R. Ghimire. . 2019. Efficacy of cover crops on weed suppression, wheat yield, and water conservation in winter wheat–sorghum–fallow. Crop Sci. 59: 1745–1752. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P. R., W. T. Lanier, and S. Brandt. . 2001. Using growing degree days to predict plant stages. Montguide MT200103 AG 7/2001. Cooperative Extension Service, Montana State University, Bozeman.

- Miller, P. R., E. J. Lighthiser, C. A. Jones, J. A. Holmes, T. L. Rick, and J. M. Wraith. . 2011. Pea green manure management affects organic winter wheat yield and quality in semiarid Montana. Can. J. Plant Sci. 91: 497–508. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dea, J. K., P. R. Miller, and C. A. Jones. . 2013. Greening summer fallow with legume green manures: on-farm assessment in north-central Montana. J. Soil Water Conserv. 68: 270–282. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, J., F. G. Blanchet, M. Friendly, R. Kindt, P. Legendre, D. McGlinn, P. R. Minchin, R. B. O’Hara, G. L. Simpson, P. Solymos, . et al. 2019. vegan: Community ecology package. R package version 2.5-6. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan [Google Scholar]

- Padbury, G., S. Waltman, J. Caprio, G. Coen, S. McGinn, D. Mortensen, G. Nielsen, and R. Sinclair. . 2002. Agroecosystems and land resources of the northern Great Plains. Agron. J. 94: 251–261. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, G. A., A. J. Schlegel, D. L. Tanaka, and O. R. Jones. . 1996. Precipitation use efficiency as affected by cropping and tillage systems. J. Prod. Agric. 9: 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, G. P. 2015. A sustainable agriculture? Daedalus 144: 76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Scheelbeek, P. F. D., F. A. Bird, H. L. Tuomisto, R. Green, F. B. Harris, E. J. M. Joy, Z. Chalabi, E. Allen, A. Haines, and A. D. Dangour. . 2018. Effect of environmental changes on vegetable and legume yields and nutritional quality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115: 6804–6809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheaffer, C. C., and P. Seguin. . 2003. Forage legumes for sustainable cropping systems. J. Crop Prod. 8: 187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Siemann, E., D. Tilman, J. Haarstad, and M. Ritchie. . 1998. Experimental tests of the dependence of arthropod diversity on plant diversity. Am. Nat. 152: 738–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R. G., L. W. Atwood, F. W. Pollnac, and N. D. Warren. . 2015. Cover-crop species as distinct biotic filters in weed community assembly. Weed Sci. 63: 282–295. [Google Scholar]

- Snapp, S. S., S. M. Swinton, R. Labarta, D. Mutch, J. R. Black, R. Leep, J. Nyiraneza, and K. O’Neil. . 2005. Evaluating cover crops for benefits, costs and performance within cropping system niches. Agron. J. 97: 322–332. [Google Scholar]

- Soil Survey Staff, NRCS. 2018. Soil Survey Staff, Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Web Soil Survey. Retrieved at: https://websoilsurvey.sc.egov.usda.gov/. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland, K. D. 1975. The diet of some predatory arthropods in cereal crops. J. Appl. Ecol. 12: 507–515. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, D. L., D. J. Lyon, P. R. Miller, S. D. Merrill, and B. G. McConkey. . 2010. Soil and water conservation advances in the semiarid Northern Great Plains, pp. 81–102. In T. M. Zobeck and W. F. Schillinger (eds.), Soil and water conservation advances in the United States. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Hobken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Thiessen Martens, J., and M. Entz. . 2011. Integrating green manure and grazing systems: a review. Can. J. Plant Sci. 91: 811–824. [Google Scholar]

- Tilman, D., C. Balzer, J. Hill, and B. L. Befort. . 2011. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 20260–20264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA, NRCS. 2020. The PLANTS Database. National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC. (http://plants.usda.gov). (accessed 25 February 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Western Regional Climate Center. 2020. (https://wrcc.dri.edu).

- Wickham, H. 2016. ggplot2 citation info. Springer-Verlang, New York. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.