Abstract

The role of the Spanish-speaking media is crucial for how Latinx communities learn about seeking help when experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV). This study investigated the IPV help-seeking messages disseminated by the Spanish-speaking media in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic. We engaged in an exploratory content analysis of videos from Univision’s main website, the most-watched Spanish-speaking media network in the U.S. We searched for videos related to IPV help-seeking posted from March 19–April 21, 2020—including the weeks after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic and the U.S. mandated a shelter-in-place. After assessing inclusion criteria, 29 videos were analyzed. Data were analyzed using basic content analysis to determine frequencies and inductive interpretive content analysis to code for help-seeking messages. We identified eight manifest messages related to seeking help when experiencing IPV in times of a crisis: (1) contact a professional resource; (2) contact law enforcement; (3) contact family, friends, and members of your community; (4) create a safety plan; (5) don’t be afraid, be strong; (6) leave the situation; (7) protect yourself at home; and (8) services are available despite the pandemic. We found that the manifest messages alluded to three latent messages: (1) it is your responsibility to change your circumstances; (2) you are in danger and in need of protection; and (3) you are not alone. IPV and media professionals should ensure a structural understanding of IPV in their help-seeking messages and avoid perpetrating stigmatizing and reductionist messages.

Keywords: Latinx, Domestic violence, Violencia de género, Violencia doméstica, Univision, Spanish-speaking communities, Television networks, IPV

Although the prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) is similar across racial and ethnic groups, its consequences disproportionally affect Latinx communities due to socioeconomic disparities (Stockman et al. 2015) and structural conditions (O’Neal and Beckman 2017). Latinx individuals, particularly immigrants or non-English speakers, face multiple challenges accessing IPV services (Postmus et al. 2014). These challenges magnify in times of crisis, such as during the 2020 coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The rapid spread of COVID-19 caused states across the nation to implement stay-at-home orders, social isolation, and travel restrictions to contain the disease (Haffajee and Mello 2020). As a result, IPV incidents increased drastically (Boserup et al. 2020). Calls for improved modalities to reach IPV survivors in crisis included the use of strategic media campaigns (Boserup et al. 2020; Kaukinen 2020). The media, mainly news outlets, play a unique role in the provision and diffusion of information to the Spanish-speaking community because they are responsible for providing service announcements in time of crisis (Benavides and Arlikatti 2010). Thus, the news networks have the capacity to reach a broad audience and provide support for Latinx IPV survivors. However, the role of the Spanish language media in delivering information to those experiencing IPV in times of national crises has not yet been explored. To address this gap, our study examined the IPV help-seeking messages shared through the Spanish-speaking media during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To achieve the purpose of our study, we used Univision’s main website to collect Spanish-language news videos related to IPV and COVID-19 and qualitative methods to analyze the data. Specifically, we used content analysis to identify the help-seeking messages and thematic analysis to analyze such messages. Our study aimed to explore the IPV help-seeking messages that the Spanish-speaking media disseminated during a health crisis to improve current efforts to address IPV in the Spanish-speaking community.

IPV Help-Seeking

Like in the general population, IPV is prevalent in the Latinx community. About 34% of Latinx women and 30% of Latinx men experience IPV at some point in their lives (Smith et al. 2017). IPV may lead to developing physical and mental health problems (Jordan et al. 2010; Loxton et al. 2017), which are especially detrimental for Latinx individuals due to existing inequities. For example, Bonomi et al. (2009) found that Latina IPV survivors have higher rates of poor physical and mental health than non-Latina IPV survivors. Therefore, service utilization is paramount to improve IPV survivors’ well-being and reduce re-victimization (Marrs Fuchsel and Brummett 2020; Trabold et al. 2020). Nevertheless, Latinx individuals face multiple barriers to accessing services due to systemic oppression, forcing them to stay in violent relationships (Postmus et al. 2014). For example, immigrant Latinx individuals may fear police involvement based on mistreatment experiences, discrimination, or anti-immigration sentiment in the U. S. (Becerra et al. 2017). Fear of deportation exacerbated during the Trump administration (Hing 2018) deters many others from obtaining assistance (Rizo and Macy 2011). Additionally, a lack of English-language proficiency and service availability or unawareness of resources pose further challenges to Latinx individuals (Rizo and Macy 2011; Robinson et al. 2020). Liang et al. (2005) proposed a theoretical framework to better understand the factors influencing a survivor’s decision to seek help for IPV.

The Help-Seeking Process

Liang et al.’ (2005) framework focuses on IPV survivors’ cognitive process leading to the intentional action of looking for help. This framework incorporates the influence of individual, interpersonal, and sociocultural factors, emphasizing that the help-seeking process is iterative, in which feedback loops are ongoing. According to Liang et al. (2005), the help-seeking process consists of three steps: problem recognition and definition, the decision to seek help, and selecting a help provider.

The problem recognition and definition step in this model entails the interpretation of abusive experiences as such. Individuals who are ready to make changes in their life may recognize abusive behaviors more readily. On the other hand, the lack of awareness about what constitutes violent behaviors might limit the recognition of IPV as a problem (Liang et al. 2005). One way in which the recognition of abusive behaviors can be influenced is through its portrayal in the media (Carlyle 2017). The second step in the help-seeking process model, deciding to seek help, depends on two cognitive processes. One process is the abusive behaviors becoming undesirable, and the second process is acknowledging the violence is likely to continue without external help.

The last step of the help-seeking process refers to the identification of a source of support. After abusive behaviors are recognized and individuals decide to seek help, they determine where and from whom to ask for help, often engaging in a benefit analysis. Determining whether seeking help is feasible and beneficial depends in part on the availability and awareness of resources, which influences the selection of service providers. Because of the news outlets’ broad reach, they are well-positioned to promote information related to IPV services and assist individuals during their help-seeking process (Carlyle et al. 2014).

Media and IPV

Media influences the perception of social problems (Carlyle 2017) and serves to provide education and information (Benavides and Arlikatti 2010). News broadcasting can influence the help-seeking process by shaping the identification of behaviors within a partnership as abusive, promoting awareness of available IPV resources, encouraging disclosure of IPV, and fostering actions to seek assistance to leave a violent relationship (Carlyle et al. 2014). With the growth of the Spanish language media (Benavides and Arlikatti 2010), there is a greater opportunity to communicate with otherwise hard to reach Latinx IPV survivors.

Although the Spanish language media produces similar content to English language news outlets, it is delivered within the Latinx context (Gomez-Aguinaga 2020). Unfortunately, assessments about the media messages communicated to Latinx Spanish-speaking IPV survivors seem to be limited. This lack of knowledge is disconcerting because a vast majority of Latinx individuals (68%) consume their news in Spanish, despite English language proficiency (Lopez and González-Barrera 2013). The large percentage of Latinx people engaging in Spanish media consumption is not surprising since almost 38 million Latinx individuals speak Spanish at home, not counting unauthorized immigrants (Hernández-Nieto et al. 2017). The most popular platform for news in the Latinx community is the television (Lopez and González-Barrera 2013). Univision’s network, a Spanish-language media company, has the largest nationwide Latinx viewership (Hernández-Nieto et al. 2017). In 2020, their network averaged 1.4 million viewers during primetime (Univision Communications Inc. 2020a). Between the week of March 16 and March 20, 2020, Univision’s audience totaled 1.7 million, becoming the leading Latinx media company (Univision Communications Inc. 2020b). Despite this network’s extensive reach, little is known about the messages they provide to assist those experiencing IPV during a national crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

COVID-19 and IPV

The measurements enacted to control the spread of COVID-19 seem to have increased IPV incidents, particularly at residential locations (Boserup et al. 2020; McLay 2021). Social isolation and stay-at-home orders meant that many IPV survivors were stuck at home with violent partners. These restrictions might have created more opportunities for control and abusive behaviors (Van Gelder et al. 2020). The closure of businesses and schools and job losses added to the stress already experienced due to the pandemic, exacerbating the risk for violence (Kaukinen 2020). Quarantine might have also increased alcohol use (Brooks et al. 2020), which might be a risk factor for IPV (Foran and O'Leary 2008).

Although the outbreak of COVID-19 was widespread, some states were more impacted than others. As of April 13, 2020, only four weeks after the outbreak became a pandemic (Cucinotta and Vanelli 2020), thirteen states had more than 10,000 confirmed cases of the novel coronavirus (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2020). Instructions to stay at home were issued to all of their residents (Mervosh et al. 2020). These states included those with the largest Latinx populations (i.e., California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, and Texas), accounting for 77% of the U.S. Latinx population (Hernández-Nieto et al. 2017). That is, the measurements implemented to curve the pandemic affected at least 44 million Latinx individuals in the first month since COVID-19 became a national emergency. With such a large number of Latinx individuals affected by the stay-at-home orders, likely getting their news through the Univision network, it is critical to identify what messages they received and determine whether those messages foster or hinder IPV help-seeking behaviors.

Current Study

Although the Spanish-speaking media plays a key role in Latinx communities, the messages they share about IPV, especially in times of crisis, are unknown. Thus, this study addresses this gap by exploring the IPV help-seeking messages disseminated by the Spanish-speaking media (i.e., Univision) in the U.S. during the most recent health crisis, COVID-19. The research question guiding this study was: What are the IPV help-seeking messages disseminated by the Spanish-speaking media in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Methodology

To answer the research question, we engaged in an exploratory content analysis of videos from Univision’s main website, the most-watched Spanish-speaking media network in the U.S. Content analysis is a systematic technique for developing categories out of large amounts of data like documents, art, and videos (Stemler 2000). Hence, content analysis aids in the process of exploring and understanding the explicit and implicit messages present in media messages. Content analysis has been employed to understand health-related issues like obesity (Yoo and Kim 2012) and Alzheimer’s disease (Tang et al. 2017). Moreover, content analysis has also been utilized to analyze the portrayal of IPV in print media (Kelly and Payton 2018).

Data Collection

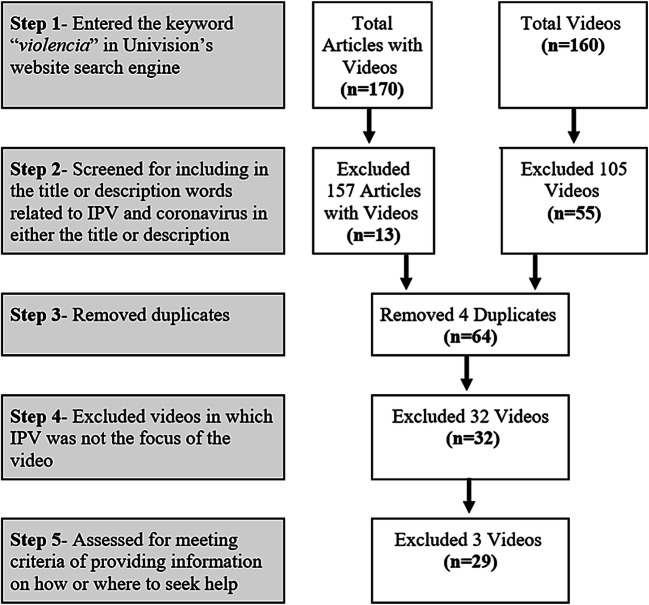

We collected data from Univision, the largest and most-watched Spanish-speaking media outlet in the U.S. Hence, the videos resulting from the search were all in Spanish. We utilized the search engine available on Univision’s main website (univision.com). The main website contains general publications made by Univision, as well as publications from local Univision subsidiaries. First, we entered the keyword “violencia” (violence) because in Spanish many of the IPV terms incorporate this word, including violencia doméstica, violencia de género, violencia familiar, violencia intrafamiliar, and violencia contra la mujer (domestic violence, gender-based violence, family violence, intrafamilial violence, and violence against women). We conducted a search for the “the last month” option in Univision’s search engine—the most adequate preset timeframe alternative, given that the other options were “this week,” “this year,” and “any dates.” We conducted the search between April 19, 2020, and April 21, 2020. Thus, “the last month” covered March 19, 2020, to April 21, 2020. This timeframe included the week after World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic on March 11, and the weeks leading up to and following the federal mandate for shelter-in-place on March 29, 2020. Both of these events, COVID becoming a pandemic and shelter-in-place mandates, were critical for the increase of families staying at home with their abusers. We also filtered the search for “articles” and “videos” as some articles contained embedded videos as well. A total of 170 hits for articles and 160 hits for videos emerged from the initial search.

Second, the results were screened for terms related to IPV, including terms like violencia, abuso, abusiva, abusivo, and maltrato (violence, abuse, abusive, and maltreatment) and words related to the coronavirus, including terms like COVID-19, pandemia (pandemic), cuarentena (quarantine), and aislamiento (isolation) in either the title or description of the article or video. A total of 13 articles with embedded videos and 55 videos met the criteria for including both terms or their variations (n = 68). We continued to add new keywords as we learned about the media’s verbiage to refer to IPV. This iterative process allowed us to understand how users may be able to find the content.

Third, we compared the articles and the videos and removed four duplicated videos (n = 64). We then read the titles and summaries and watched the videos to exclude content in which IPV was not the focus of the video (e.g., a video reported the cleaning of the offices of the domestic violence police unit after concerns of some officers being exposed to COVID-19) and about reports outside of the U.S. One researcher reviewed the results for articles, while another researcher reviewed the results for videos. Both researchers reviewed the content of the videos that did not clearly fit the inclusion criteria. A total of 32 videos met the criteria for inclusion in this step. Finally, the two researchers screened the 32 results separately to assess for meeting criteria for providing information on how or where to seek help (either formal or informal). Then, both researchers compared their inclusion lists. A total of 29 videos met final inclusion for data analysis. Figure 1 shows this process.

Fig. 1.

Data Collection Procedure

Data Analysis

We employed Drisko and Maschi’s (2016) guidelines for content analysis to identify the help-seeking messages and then Braun and Clark’s (2006) framework for thematic analysis to analyze the messages. We charted each video using Excel tables to document the following information: (1) title of the video; (2) length of the video; (3) date of publication, (4) link to the video; (5) source (i.e., national or local news); (6) perceived gender of media staff; (7) perceived gender of the external person(s); (8) help-seeking messages (e.g., provide strategies, provide resources); (9) source of information (e.g., WHO, local expert); (10) if resources were provided, are they local, national, or both; (11) if resources were local, city and state of the resources; and (12) population addressed (i.e., who is the recipient of IPV). We then employed basic content analysis to determine frequencies for each of the identified sections. Basic content analysis serves as a tool to quantitatively “summarize or describe data” (Drisko and Maschi 2016, p. 58).

We also used inductive interpretive content analysis to code for help-seeking messages delivered in the videos. Interpretive content analysis allows for inferring the explicit and implicit intention of a text, including verbal communication, based on context. According to Drisko and Maschi (2016), “[r]esearchers may use interpretive content analysis to describe content and meanings, to summarize large data sets, and to make inferences about intentions, thoughts, and feelings based on speech or other forms of communication” (p. 65).

We coded for both manifest (overt) and latent (covert) messages about IPV help-seeking. Manifest messages are the literal messages of a statement, while latent messages are the underlying or implied messages that emerge from the literal messages. We utilized Braun and Clarke’s (2006) steps for thematic analysis to generate codes and themes based on the visual and spoken messages. The two researchers coded latent messages separately and then compared them to increase validity and replicability. The two researchers agreed on most codes. Both the manifest and latent sets of codes were exhaustive, exclusive, and enlightening (Rose 2016).

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness in this study was sought by the use of reliability and the authors’ reflexivity about their own identities.

Reliability

After excluding videos that did not meet the criteria for providing information on how or where to seek help, two researchers separately screened the videos that appeared to meet the criteria (n = 32). They then compared their inclusion lists. There was an 87% agreement between the two researchers on the inclusion of videos for the final sample, which is above the 80% agreement needed for reliability in content analysis (Drisko and Maschi 2016). Disagreements were discussed between both researchers, which led to a 100% agreement on the selection of the final sample (n = 29).

Subjectivity Statements

We recognize that the interpretation of the data is a construction based on our identities and experiences. The first author is a bilingual gay Latino with practice and research experience in the area of Latinx mental health. As a clinical social worker, he has also participated in various media interviews. His experiences influence how he evaluates the media messages in general and the discourse of the reporters and experts in particular. The second author is a bilingual immigrant Latina researching IPV among Latinas. She has practical social work experience with immigrant communities. These experiences inform her approach to the media messages directed to the immigrant and Latinx populations. The third author is a cultural anthropologist who has worked in the IPV field as a practitioner and researcher for over a decade. As a white, cisgender woman, her experiences and approach to data analysis are informed by this identity, as well as her work specifically in Latin America and working with Latinx communities in the U.S.

Results

Descriptive Information of Videos

The 29 videos were posted between March 23, 2020, and April 17, 2020. The length of the videos was between 27 seconds and almost seven minutes. Most videos (59%) were between two and three minutes long. Of the 29 videos, 24 (83%) were posted by local subsidiaries of Univision. Nine videos were from Texas (Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, and San Antonio), five from California (Bay Area, Fresno, Los Angeles, and Sacramento), and four from Illinois (Chicago). Other subsidiaries that published one video each included Georgia (Atlanta), Pennsylvania (Philadelphia), Arizona, North Carolina, New York, and Florida (Miami-Ft. Lauderdale). Most reporters were perceived to be men (59%), while most interviewees were perceived as women (66%). Table 1 contains descriptive information for each video.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information of Videos

| (n = 29) | Length of Video (mins:secs) | Date of Publication | Location of the Video | Perceived Gender of Media Staff | Perceived Gender of External Person(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2:30 | 4/3/2020 | Atlanta | Man | Woman |

| 2 | 3:40 | 4/17/2020 | Dallas-Fort Worth | Man | Man |

| 3 | 0:52 | 4/7/2020 | Houston | Woman | Man |

| 4 | 2:26 | 3/30/2020 | Philadelphia | Woman | Woman |

| 5 | 2:50 | 4/7/2020 | National | Both | N/A |

| 6 | 2:42 | 4/7/2020 | Dallas-Fort Worth | Both | Woman |

| 7 | 2:58 | 3/25/2020 | Fresno | Man | Woman |

| 8 | 6:46 | 3/24/2020 | National | Man | Both |

| 9 | 2:21 | 4/6/2020 | Chicago | Man | Both |

| 10 | 2:29 | 4/8/2020 | San Antonio | Both | Woman |

| 11 | 2:27 | 4/7/2020 | Sacramento | Woman | Both |

| 12 | 2:00 | 4/10/2020 | Bay Area | Woman | Both |

| 13 | 2:22 | 3/27/2020 | Houston | Both | Woman |

| 14 | 3:15 | 4/13/2020 | Chicago | Man | Woman |

| 15 | 2:20 | 4/10/2020 | Arizona | Man | Both |

| 16 | 27 s | 4/9/2020 | Chicago | Man | N/A |

| 17 | 50 s | 3/28/2020 | Houston | Man | Woman |

| 18 | 1:33 | 3/25/2020 | National | Man | Woman |

| 19 | 2:17 | 3/23/2020 | San Antonio | Man | Woman |

| 20 | 3:15 | 3/27/2020 | North Carolina | Both | Man |

| 21 | 3:04 | 4/4/2020 | New York | Both | Woman |

| 22 | 2:44 | 4/6/2020 | National | Man | Woman |

| 23 | 1:47 | 4/1/2020 | Chicago | Man | Woman |

| 24 | 2:22 | 4/12/2020 | Miami-Ft. Lauderdale | Man | Woman |

| 25 | 52 s | 4/6/2020 | Houston | Man | Woman |

| 26 | 2:04 | 4/3/2020 | Los Angeles | Both | Woman |

| 27 | 2:58 | 3/31/2020 | Houston | Man | Woman |

| 28 | 2:03 | 3/23/2020 | Sacramento | Woman | Woman |

| 29 | 1:47 | 4/7/2020 | National | Man | Woman |

IPV Information

Reporters employed the use of interviewees or resources for the information provided in 27 out of the 29 videos. Moreover, 15 videos cited only one source, 10 videos cited two sources, and two videos cited three sources. Local experts (e.g., counselors and staff at shelters) were the most utilized sources for IPV information (21 occasions), followed by law enforcement and judicial staff (10 occasions). Other sources of information regarding IPV included statements by the United Nations, IPV survivors, staff from national domestic violence organizations, and other government staff. A total of 21 videos (72%) included background dramatization videos or images depicting IPV situations. All of these 21 videos and images depicted women as recipients of physical violence.

Help-Seeking Resources

A total of 25 videos provided information about resources where individuals could seek help for IPV (86%). However, some of the videos mentioned the name of the resources but did not provide their contact information or vice versa. Hence, we had to do an online search on multiple occasions to link the name and location of resources with the contact information provided and vice versa. Information about local resources was provided 62% of the time, while national resources were mentioned 38% of the time. A total of four videos did not provide information about resources. Of the 29 videos, 11 videos provided the national domestic violence hotline’s contact information, and five videos asked survivors to call 911.

Help-Seeking Messages

Manifest and latent codes were identified in the data. Manifest codes were the literal messages disseminated across the videos about IPV help-seeking. Latent codes were the underlying messages of what IPV help-seeking means. Table 2 displays more information about these messages and examples of related quotes. The quotes are provided in the English translation, followed by the original statements in Spanish in italics and inside parenthesis. In some examples, contextual information has been provided inside brackets.

Table 2.

Latent and Manifest Themes Regarding IPV Help-Seeking

| Latent Themes | Manifest Themes | Messages | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| You are not alone | Contact a professional resource | Contact a professional resource either local or national resources, via text, chat, email, or phone call. Resources are free, anonymous, and bilingual. Victims, perpetrators, and others who know about an IPV situation can call. They can help with providing information and resources and with creating a plan. |

A staff member from a local domestic violence agency in Chicago stated: “Depending on the situation and the case, we can refer them to the resources they need and give them information. The services are completely free and we are not asking for any of their specific information. Everything is confidential.” (“Dependiendo de la situación y el caso podemos referirlos a los recursos que necesitan y darles la información. Los servicios son completamente gratuitos y no estamos pidiendo ninguna información específica de ellos. Todo es completamente confidencial.”) |

| Contact family, friends, and members of your community | Contact family, friends, and members of your community, including nearby businesses and neighbors. Keep them informed about your situation and ask for their help. |

The chief of police from Houston stated: “Report the domestic violence. Go to a business, to a house, to a friend’s place.” (“Reporte la violencia doméstica. Vaya a un negocio, vaya a una casa, vaya al lugar de un amigo.”) |

|

| Services are available despite the pandemic | The courts are still open for IPV cases. Already established restriction orders are still valid and people are able to obtain new ones. Counseling and shelters are still available. Many services are available via email or phone. |

A reporter located in Miami stated: “The courts have put in motion some special measures. Some courts, for example, have decided to extend the protection orders. Other judges are even doing virtual hearings using video cameras to see urgent cases.” (“Los tribunales han puesto en marcha algunas medidas especiales. Algunos tribunales, por ejemplo, han decidido extender las órdenes de restricción y de protección. Otros jueces están incluso recurriendo a audiencias virtuales utilizando videocámaras para atender casos de urgencias.”) |

|

| You are in danger and in need of protection | Contact law enforcement | It is essential to report the violence to law enforcement. Contact law enforcement, including the courts, police, and 911. Call if you feel you are at risk or unsure of what to do. Others who know about an IPV situation can also report it. |

A local police officer from Houston stated: “But the first thing [is that] they have to call Houston’s police department to report what is happening.” (“Pero lo primero [es que] ellos tienen que llamar al departamento de la policía de Houston para reportar lo que está pasando.”) |

| Leave the situation | Leave the situation when the physical violence is strong and when you feel overwhelmed. |

A local expert from Dallas-Fort Worth stated: “When there is a type of domestic violence that it is too strong, it is better to leave, to seek help, because there can be fatal consequences.” (“Cuando haya un tipo de violencia física muy fuerte, es mejor irse, buscar ayuda, porque pueden haber consecuencias fatales.”) |

|

| Protect yourself at home | Protect yourself physically at home. Avoid confrontation and being in enclosed spaces in the house. Have spaces at home that are safe. |

A local expert from Houston stated: “Find a way of not enclosing yourself in rooms where there are weapons. For example, if there is an argument or altercation, do not hide in a bathroom or kitchen where obviously there can be more weapons.” (“Encuentre maneras de no encerrarse en cuartos donde haya armas. Por ejemplo, si hay una discusión o una altercación, no se esconda en un baño o en una cocina donde obviamente puede haber más armas.”) |

|

| It is your responsibility to change your circumstances | Create a safety plan |

Create a safety plan: 1. Locate the exits of your home 2. Do not be in a room where guns are present 3. Have a bag ready in a hidden place (with important documents, clothes, cash, basic items) 4. Talk to your neighbors and family 5. Create a code word with family members 6. Identify safe places to go for help and food 7. Save or memorize phone numbers of shelters 8. Engage in self-care. |

An expert in the national website stated: “The first thing [is] to create a safety plan. For example, take measures in case the abuser can take control of the phone or of communications. Then, stay in contact with a family member. To have code words that can be used when calling someone that can come help us at home if necessary.” (“Lo primero [es] crear un plan de seguridad. Por ejemplo, tomar medidas por si el abusador puede tomar control del teléfono, de las comunicaciones. Luego, mantener contacto con la familia. Tener palabras claves que se puedan utilizar a la hora de llamar a alguien que pueda venir a auxiliarnos a casa en caso de ser necesario.”) |

| Don’t’ be afraid, be strong | Report your situation. This is the first step to freedom. It doesn’t matter if you are undocumented. You are strong and cannot be silent. Keep your hope and strength. Be brave. Don’t feel stuck. |

An anonymous survivor of IPV from Philadelphia said: “A woman is strong inside and do not stay silent.” (“La mujer es fuerte por dentro y no se queden calladas.”) |

Manifest Messages

Eight manifest messages emerged for how to seek help when experiencing IPV during the COVID-19 crisis. None of the videos communicated all of the eight manifest messages, although multiple messages were disseminated per video. The eight manifest themes were: (1) contact a professional resource (n = 20); (2) contact law enforcement (n = 11); (3) contact family, friends, and members of your community (n = 9); (4) create a safety plan (n = 6); (5) don’t be afraid, be strong (n = 9); (6) leave the situation (n = 5); (7) protect yourself at home (n = 5); and (8) services are available despite the pandemic (n = 5). Messages regarding contacting a professional resource suggested viewers reached out to local agencies (their contact information was often shared in the video) and the national help-line. Contacting law enforcement was mentioned in the context of safety, asking viewers to call 9–1-1, the local police departments, or the courts. Safety planning included suggestions like gathering important documents, making an emergency bag, and memorizing important numbers. The message of “don’t be afraid, be strong” encompassed comments like “If you are a victim, don’t be afraid” (“Si es víctima, no tenga temor”) and “A woman is strong inside and do not stay silent” (“La mujer es fuerte por dentro y no se queden calladas”). Leaving the situation was encouraged in times where the victim felt their life was in danger. These manifest messages could be collapsed into three underlying messages directed towards IPV help-seeking during the pandemic.

Latent Messages

Eleven broader latent messages emerged initially. We then reviewed these themes and collapsed overlapping themes, leading to a total of three themes: (1) you are not alone; (2) you are in danger and in need of protection; and (3) it is your responsibility to change your circumstances. Table 2 displays more information about these themes and their relationship with the eight manifest themes. The first latent message, “you are not alone,” is related to the following manifest messages: contact a professional resource; contact family, friends, and members of your community; and services are available despite the pandemic. An example of this latent message can be seen when a staff member from a local domestic violence agency encouraged viewers to contact them as a professional resource,

Depending on the situation and the case, we can refer them to the resources they need and give them information. The services are completely free, and we are not asking for any of their specific information. Everything is confidential.

(Dependiendo de la situación y el caso podemos referirlos a los recursos que necesitan y darles la información. Los servicios son completamente gratuitos y no estamos pidiendo ninguna información específica de ellos. Todo es completamente confidencial.)

The second latent message, “you are in danger and in need of protection,” is connected to the following manifest messages: contact law enforcement; leave the situation; and protect yourself at home. An example of this latent message is evident when a local expert encouraged viewers to leave the IPV situation,

When there is a type of domestic violence that it is very strong, it is better to leave, to seek help, because there can be fatal consequences.

(Cuando haya un tipo de violencia física muy fuerte, es mejor irse, buscar ayuda, porque pueden haber consecuencias fatales.)

The third latent message, “it is your responsibility to change your circumstances,” is linked to the following manifest messages: create a safety plan; and don’t be afraid, be strong. An example of this latent message is present when an anonymous survivor of IPV told viewers, “A woman is strong inside and do not stay silent.” (“La mujer es fuerte por dentro y no se queden calladas.”). These findings have critical implications for help-seeking, IPV service providers, and media staff.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the IPV help-seeking messages disseminated by the Spanish-speaking media in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that there were eight consistent manifest messages as well as three latent messages embedded in these sources. Altogether, these messages were aimed at shaping the actions and attitudes of Latinx IPV survivors. The manifest messages that were communicated to IPV survivors included: (1) contact a professional resource; (2) contact law enforcement; (3) contact family, friends, and members of your community; (4) create a safety plan; (5) don’t be afraid, be strong; (6) leave the situation; (7) protect yourself at home; and (8) services are available despite the pandemic. The latent messages included: (1) you are not alone; (2) you are in danger and in need of protection; and (3) it is your responsibility to change your circumstances. These manifest and latent messages generally communicated to Latinx IPV survivors that they should seek formal interventions as well as informal resources in their communities to protect themselves from harm.

Structural Barriers to Help-Seeking

Although Spanish language media is meant to contextualize information for a Latinx audience (Gomez-Aguinaga 2020), there are a variety of ways in which the messages contained in these media sources fail to account for the structural difficulties that Latinx IPV survivors face. With respect to the manifest messages, the message that survivors ought to contact a professional resource is only effective if those professional resources are equipped to help Latinx survivors. While there have been significant efforts by the IPV movement to provide Spanish language services that are more aware of the particular needs of Latinx communities, there is still much work to be done in this arena (Parson et al. 2016; Reina et al. 2014). Immigrant Spanish-speaking survivors, in particular, may face a range of unique difficulties (O’Neal and Beckman 2017; Postmus et al. 2014; Rizo and Macy 2011). For example, these survivors may have their immigration status weaponized against them by an abuser, who might threaten to have them deported or to hurt family members in their country of origin if they are deported (Raj & Silverman, 2002). Consequently, it is vital that news outlets make sure that they are providing resources for IPV centers and hotlines that have Spanish language counselors as well as knowledge of—and resources for—Latinx communities specifically.

Encouraging Latinx survivors to contact law enforcement also fails to acknowledge the current climate of xenophobia and anti-immigration and the fear of detention and deportation by the federal U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency (Hing 2018). As the Black Lives Matter movement has highlighted, fear of contacting authorities may be even higher for Afro-Latinx individuals, who must also contend with the realities of police brutality towards Black communities in the U.S. (Contreras et al. 2020). Moreover, immigrants may bring fear of authorities with them from their home countries that prevent them from seeking such help in the U.S. (Wilson 2014). Additionally, immigrant survivors face particular legal constraints that most IPV centers are not equipped to manage. For instance, many survivors must be able to afford legal assistance or spend time and resources navigating local providers to find pro-bono assistance while also spending subsequent time and resources within court systems (Salcido and Adelman 2004; Villalón 2010).

To recognize these barriers, media stories around IPV should prioritize information about resources beyond the police—a resource with which most people are already familiar. In particular, they should emphasize where people can find COVID-accessible, Spanish speaking IPV counselors—whether that be a local center or a national, Latinx-focused hotline—who understand the constraints often found in Latinx communities. By engaging in safety planning with such a counselor, individual survivors can develop the best course of action for their particular circumstances. Offering this type of information could have a positive effect on all aspects of a survivor’s cognitive processing with respect to IPV (Liang et al. 2005), including a survivor’s ability to recognize and define the problem, make the decision to seek help, and find a supportive provider.

COVID-19-Related Barriers to Help-Seeking

Concerning additional structural constraints, the message that survivors ought to leave the situation is also highly fraught. Particularly during a national health crisis, job loss and lack of job security are prevalent. Thus, survivors may be even more dependent on abusers financially, for childcare, or for health insurance, in spite of the reality that confinement at home creates more opportunities for abuse (Van Gelder et al. 2020). These challenges may be especially true for survivors who are older and have disabilities and other health constraints that limit their ability to work during the COVID-19 pandemic. In general, while IPV services can provide many short-term resources such as safe houses and court advocacy, their ability to assist with necessary long-term resources for rebuilding a life without support from one’s partner such as stable housing, job training, childcare, and healthcare are limited at best—what Parson (2013) terms a “pragmatic” rather than a comprehensive approach to service provision. The manifest messages reinforce the latent message that the survivor is in danger and in need of protection. While the dangers of IPV are necessary to address, the risks of leaving the resources provided within that relationship and the conflicts around contacting law enforcement must also be acknowledged (Mehrotra et al. 2016). In light of these realities, media outlets can also emphasize measures that can be implemented while still living with one’s abuser, such as developing a safety plan with an IPV counselor to employ in case of an emergency.

Help-Seeking Messages

Moreover, the implication that survivors need to be strong and unafraid is also problematic. This manifest message connects to the latent message that it is the survivor’s responsibility to change their circumstances. Such messaging implies a problematic neoliberal orientation towards IPV. A neoliberal orientation towards IPV encourages survivors to take personal responsibility for their safety rather than focusing on the societal forces working against them (Mehrotra et al. 2016). This messaging fails to account for the structural and social conditions that make IPV a global phenomenon. The original feminist orientation of the IPV movement highlighted how IPV is the product of power structures in society that perpetuate the abuse of certain groups of people at the hands of others—in many (but certainly not all) cases, the abuse of women at the hands of men (Bart and Moran 1993; Johnson and Ferraro 2000). Espousing the idea that it is an individual survivor’s responsibility to extract themselves from an abusive situation veils both these power structures as well as the structural conditions that perpetuate this abuse and make it difficult to leave, particularly for additionally marginalized and discriminated against groups. Rather than perpetuating these problematic messages, in addition to providing information, news outlets can play an important part by highlighting these power structures in their news stories about IPV and using their platform to advocate for systemic change.

By focusing on able-bodied, cisgender, and heterosexual women as the sole targets of IPV, media messages ignore the realities of other Latinx marginalized groups. For instance, LGBTQ+ Latinx individuals experience IPV at a higher rate. This is the case of LGBTQ+ communities in both Latin America (Swan et al. 2019) and the U.S. (Whitfield et al. 2018). In the U.S., for example, a national transgender survey found that transgender Latinx individuals disproportionately experience high IPV rates, with transgender men, unemployed individuals, and disabled people being at an even higher risk (James and Salcedo 2017). These marginalized groups face additional structural and interpersonal challenges. For instance, for many transgender Latinx individuals, IPV was perpetuated by partners who degraded them for being transgender and threatened to disclose their identities to others (James and Salcedo 2017). This lack of diversity in help-seeking messages misses an opportunity to reach, visibilize, and bring attention to these vulnerable Latinx groups’ experiences. Instead, this diversity should be better represented in the media through the gendered language, images, and stories that are used.

Limitations and Strengths

This study has both limitations and strengths. A limitation of this study is its focus on online content, as not every Spanish-speaker has access to the internet or technology, and many may only learn about IPV through what is broadcasted on television. Moreover, this study’s results do not consider the Latinx population that is not proficient in Spanish or seeks information in English-only media. This study is also limited to Univision’s website and does not account for other television networks or the social media platforms that many people may utilize as their primary sources of information. From a data-gathering standpoint, this study’s replicability is limited to the constant addition and deletion of online content and to the data collection timeframe selected due to the immediate need to explore this issue. On the other hand, a strength of this study is its timeliness in adding to the literature a focus on help-seeking messages during an unprecedented global pandemic that has restructured the ways in which service providers deliver services and conduct outreach, and the ways survivors engage with services. Additionally, this study considers the role of the media in the cultural constructions of violence, relationships, and IPV among Spanish-speaking communities in the U.S. Finally, the results of this study aim to inform the practice of IPV professionals, as well as the media.

Recommendations for Practice

IPV Professionals

Practitioners working with Spanish-speaking IPV survivors should consider the influence that the media may have on their clients’ IPV experiences. In particular, they must consider the culturally targeted messages around violence and help-seeking that IPV survivors may absorb from Spanish-language sources. Community programs should address misconceptions that might be created by these media messages. Moreover, IPV prevention and intervention efforts must incorporate outreach efforts that are inclusive of all Latinx identities to avoid further marginalizing certain IPV survivors, such as LGBTQ+ individuals. Thus, it is recommended that IPV organizations partner with media outlets to work towards creating messages that accurately represent the dynamics of IPV and offer best practices regarding help-seeking for the Latinx community. A focus on media messages that target the unique needs of Spanish-speaking IPV survivors will be effective in accessing otherwise hard-to-reach IPV survivors and welcoming survivors who might otherwise feel alienated from IPV services.

Media Professionals

Those working with the Spanish-speaking media should consider avoiding using images or videos that perpetuate a narrow view of IPV as mere physical violence and only endured by cisgender, heterosexual women. These images and videos should not portray women as defenseless and men as hyperaggressive, as IPV does not always look as such, leading survivors to potentially minimize their situation because it does not match the media representation. Additionally, news outlets should acknowledge both the typical and the COVID-19-related constraints that may prevent Latinx survivors from seeking help, while offering information for resources that can adequately address these challenges in the Latinx community specifically. Moreover, journalists should ensure that they visually (e.g., on a tag line at the bottom of the screen) provide the audience with the name of resources and related contact information from the beginning of their reporting. Waiting until the end of a report to provide such information limits its utility as survivors may have less time to write down the information if they are even able to watch the entire video. Media networks should also consider disabling ads for videos that provide life-saving information. For example, during the data-gathering phase of this study, we had to watch 15–60 seconds in ads before watching the videos, with even more ads interrupting in the middle of the videos. A survivor of IPV may not have the time to watch these ads to obtain help-seeking messages and resources, especially during a pandemic where perpetrators are also at home and vigilantly watching. Lastly, given their powerful role in disseminating information to IPV survivors, their families, and their communities, news outlets can also discuss the broader power dynamics that perpetuate IPV and offer messages about change.

Conclusion

Spanish-speaking individuals living in the U.S. face particular challenges when seeking help for IPV, including the lack of information in Spanish. In order to overcome these barriers, education about how survivors can access resources is crucial. The media plays an essential role in how Spanish-speaking communities in the U.S. learn about IPV help-seeking. This role has been especially true during the global COVID-19 pandemic when more survivors are isolated in their homes with their abusers. Through this study, we sought to explore the IPV help-seeking messages disseminated by the Spanish-speaking media in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found several problematic aspects to these messages: they were limited to cisgender and heterosexual Latina women, encouraged their use of law enforcement as a primary resource, and replicated neoliberal attitudes towards help-seeking behaviors. Each of these aspects may be alienating to marginalized Latinx survivors and may actually discourage help-seeking behaviors. We also found that reporters were inconsistent in providing information regarding the name and contact information of resources. However, reporters engaged local experts like counselors and staff at shelters in their reporting, which aids in showing that resources at the local level are available. Given these findings, IPV and media professionals should ensure that they are disseminating IPV help-seeking messages that address the particular needs of the Latinx community and avoid perpetrating stigmatizing and reductionist narratives.

Future research should focus on the influence of Spanish-language media on seeking help from law enforcement in IPV cases, such as on the police’s response to IPV cases with Spanish-speaking survivors. If the Spanish-speaking media often suggests using law enforcement as a resource for IPV, how efficient is law enforcement at addressing survivors’ needs? Additional research targeting the local news outlets of states with the highest population of Latinx individuals and cases of COVID-19 is also worth exploring to understand the IPV-related messages disseminated among these communities. Finally, investigating the IPV help-seeking messages shared across other social media outlets and television stations is necessary to increase the body of knowledge on this topic.

Declarations

Declaration of Interest Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Footnotes

This manuscript has not been published elsewhere nor has it been submitted simultaneously for publication elsewhere.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Luis R. Alvarez-Hernandez, Email: lalvarez@uga.edu

Iris Cardenas, Email: iec11@ssw.rutgers.edu.

Allison Bloom, Email: blooma@moravian.edu.

References

- Bart P, Moran EG. Violence against women: The bloody footprints. Newbury Park: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Becerra W, Wagaman MA, Androff D, Messing J, Castillo J. Policing immigrants: Fear of deportations and perceptions of law enforcement and criminal justice. Journal of Social Work. 2017;17(6):715–731. doi: 10.1177/1468017316651995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benavides A, Arlikatti S. The role of the Spanish-language media in disaster warning dissemination: An examination of the emergency alert system. Journal of Spanish Language Media. 2010;3(1):41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi A, Anderson M, Cannon E, Slesnick N, Rodriguez M. Intimate partner violence in Latina and non-Latina women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boserup B, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020;38:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Simon W, Greenberg N, Gideon JR. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlyle KE. The role of social media in promoting understanding of violence as a public health issue. Journal of Communication in Healthcare. 2017;10(3):162–164. doi: 10.1080/17538068.2017.1373907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlyle KE, Orr C, Savage MW, Babin EA. News coverage of intimate partner violence: Impact on prosocial responses. Media Psychology. 2014;17(4):451–471. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2014.931812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html

- Contreras F, Laurent A, Abona-Ruiz M, Garsd J (2020) The afro-Latinx experience is essential to our international reckoning on race. NPR ALT.LATINO Podcast. Podcast retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2020/07/02/886568058/the-afro-latinx-experience-black-lives-matter

- Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta biomedica: Atenei Parmensis. 2020;91(1):157–160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drisko JW, Maschi T. Content analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O'Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(7):1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Aguinaga B. One group, two worlds? Latino perceptions of policy salience among mainstream and Spanish-language news consumers. Social Science Quarterly. 2020;102:238–258. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haffajee RL, Mello MM. Thinking globally, acting locally–the U.S. response to Covid-19. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(22):1–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2006740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Nieto R, Gutiérrez MC, Moreno-Fernández F. Hispanic map of the United States. Observatorio: Instituto Cervantes at FAS – Harvard University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hing B. Entering the trump ice age: Contextualizing the new immigration enforcement regime. Texas A&M Law Rev. 2018;5(2):253–322. doi: 10.37419/LR.V5.I2.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James, S. E., & Salcedo, B. (2017). 2015 U.S. transgender survey: Report on the experiences of Latino/a respondents. National Center for transgender equality and TransLatin@coalition.

- Johnson MP, Ferraro KJ. Research on domestic violence in the 1990s: Making distinctions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62(4):948–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00948.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan C, Campbell R, Follingstad D. Violence and women’s mental health: The impact of physical, sexual, and psychological aggression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6(1):607–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-090209-151437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaukinen C. When stay-at-home orders leave victims unsafe at home: Exploring the risk and consequences of intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2020;45:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09533-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J, Payton E. A content analysis of local media framing of intimate partner violence. Violence and Gender. 2018;6(1):47–52. doi: 10.1089/vio.2018.0019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Goodman L, Tummala-Narra P, Weintraub S. A theoretical framework for understanding help-seeking processes among survivors of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;36(1–2):71–84. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-6233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, M.H, & González-Barrera, A. (2013). A growing share of Latinos get their news in English. Pew research center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2013/07/latinos_and_news_media_consumption_07-2013.pdf. Access 25 Apr 2020.

- Loxton D, Dolja-Gore X, Anderson AE, Townsend N. Intimate partner violence adversely impacts health over 16 years and across generations: A longitudinal cohort study. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0178138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs Fuchsel CL, Brummett A. Intimate partner violence prevention and intervention group-format programs for immigrant Latinas: A systematic review. Journal of Family Violence. 2020;36:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00160-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLay, M. M. (2021). When “shelter-in-place” isn’t shelter that’s safe: A rapid analysis of domestic violence case differences during the COVID-19 pandemic and stay-at-home orders. Journal of Family Violence, 1–10. 10.1007/s10896-020-00225-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mehrotra GR, Kimball E, Wahab S. The braid that binds us: The impact of neoliberalism, criminalization, and professionalization on domestic violence work. Affilia. 2016;31(2):153–163. doi: 10.1177/0886109916643871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mervosh, S., Lu, D., Swales, V. (2020 20). See which states and cities have told residents to stay at home. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-stay-at-home-order.html. Accessed 25 Apr 2020.

- O’Neal E, Beckman L. Intersections of race, ethnicity, and gender: Reframing knowledge surrounding barriers to social services among Latina intimate partner violence victims. Violence Against Women. 2017;23(5):643–665. doi: 10.1177/1077801216646223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parson N. Traumatic states: Gendered violence, suffering, and care in Chile. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parson N, Escobar R, Merced M, Trautwein A. Health at the intersections of precarious documentation status and gender-based partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2016;22(1):17–40. doi: 10.1177/1077801214545023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postmus J, McMahon S, Silva-Martinez E, Warrener C. Exploring the challenges faced by Latinas experiencing intimate partner violence. Affilia. 2014;29(4):462–477. doi: 10.1177/0886109914522628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reina AS, Lohman BJ, Maldonado MM. ‘He said they’d ‘deport me’: Factors influencing domestic violence help-seeking practices among Latina immigrants. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014;29(4):593–615. doi: 10.1177/0886260513505214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizo CF, Macy RJ. Help seeking and barriers of Hispanic partner violence survivors: A systematic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2011;16(3):250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2011.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S. R., Ravi, K., & Voth Schrag, R. J. (2020). A systematic review of barriers to formal help seeking for adult survivors of IPV in the United States, 2005-2019. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 1524838020916254. 10.1177/1524838020916254. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rose G. Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. 4. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Salcido O, Adelman M. He has me tied with the blessed and damned papers: Undocumented-immigrant battered women in Phoenix, Arizona. Human Organization. 2004;63(2):162–172. doi: 10.17730/humo.63.2.v5w7812lpxextpbw. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SG, Chen J, Basile KC, Gilbert LK, Merrick MT, Patel N, Walling M, Jain A. The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2010–2012 state report. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stemler S. An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation. 2000;7:1–7. doi: 10.7275/z6fm-2e34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman JK, Hayashi H, Campbell JC. Intimate partner violence and its health impact on ethnic minority women. Journal of Women’s Health. 2015;24(1):62–79. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan, L. E. T., Henry, R. S., Smith, E. R., Aguayo Arelis, A., Rabago Barajas, B. V., Perrin, P. B. (2019). Discrimination and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration among a convenience sample of LGBT individuals in Latin America. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–18. 10.1177/0886260519844774 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tang W, Olscamp K, Choi SK, Friedman DB. Alzheimer's disease in social media: Content analysis of YouTube videos. Interactive Journal of Medical Research. 2017;6(2):e19. doi: 10.2196/ijmr.8612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabold M, McMahon J, Alsobrooks S, Whitney S, Mittal M. A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions: State of the field and implications for practitioners. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2020;21(2):311–325. doi: 10.1177/1524838018767934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Univision Communications Inc. (2020a). Univision in 2020: Another year and more no. 1s for the leading Hispanic media company in the U.S. Corporate Univision. https://corporate.univision.com/blog/2020/12/22/univision-in-2020-another-year-and-more-no-1s-for-the-leading-hispanic-media-company-in-the-u-s. Accessed 11 Jan 2021.

- Univision Communications Inc. (2020b). Univision delivers double-digit primetime audience growth, finishes among top 5 on broadcast tv among key demos. Corporate Univision. https://corporate.univision.com/blog/2020/03/24/univision-delivers-double-digit-primetime-audience-growth-finishes-among-top-5-on-broadcast-tv-among-key-demos. Accessed 12 Jun 2021.

- Van Gelder N, Peterman A, Potts A, O'Donnell M, Thompson K, Shah N, Oertelt-Prigione S. COVID-19: Reducing the risk of infection might increase the risk of intimate partner violence. EClinical Medicine. 2020;21:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalón R. Violence against Latina immigrants: Citizenship, inequality, and community. New York: New York University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield, D. L., Coulter, R. W. S., Langenderfer-Magruder, L., Jacobson, D. (2018). Experiences of intimate partner violence among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender college students: The intersection of gender, race, and sexual orientation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–25. 10.1177/0886260518812071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wilson TD. Violence against women in Latin America. Latin American Perspectives. 2014;41(1):3–18. doi: 10.1177/0094582X13492143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo JH, Kim J. Obesity in the new media: A content analysis of obesity videos on YouTube. Health Communication. 2012;27(1):86–97. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.569003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]