Abstract

Adoptive transfer of Bispecific antibody Armed activated T cells (BATs) showed promising anti-tumor activity in clinical trials in solid tumors. The cytotoxic activity of BATs occurs upon engagement with tumor cells via the bispecific antibody (BiAb) bridge, which stimulates BATs to release cytotoxic molecules, cytokines, chemokines, and other signaling molecules extracellularly. We hypothesized that the release of BATs Induced Tumor-Targeting Effectors (TITE) by this complex interaction of T cells, bispecific antibody, and tumor cells may serve as a potent anti-tumor and immune-activating immunotherapeutic approach. In a 3D tumorsphere model, TITE showed potent cytotoxic activity against multiple breast cancer cell lines compared to control conditioned media (CM): Tumor-CM (T-CM), BATs-CM (B-CM), BiAb Armed PBMC-CM (BAP-CM) or PBMC-CM (P-CM). Multiplex cytokine analysis showed high levels of Th1 cytokines and chemokines; phospho-protein signaling array data suggest that the prominent JAK1/STAT1 pathway may be responsible for the induction and release of Th1 cytokines/chemokines in TITE. In xenograft breast cancer models, IV injections of 10× concentrated TITE (3×/week for 3 weeks; 150 μl TITE/injection) was able to inhibit tumor growth significantly (ICR/scid, p < 0.003; NSG p < 0.008) compared to the control mice. We tested the key components of the TITE for immune activating and anti-tumor activity individually and in combinations, the combination of IFN-γ, TNF-α and MIP-1β recapitulates the key activities of the TITE. In summary, master mix of active components of BATs–Tumor complex-derived TITE can provide a clinically controllable cell-free platform to target various tumor types regardless of the heterogeneous nature of the tumor cells and mutational tumor.

Keywords: 3D culture model, Breast cancer, Activated T cells, Bispecific antibody, Cancer stem cells, Myeloid-derived suppressor cells, Th1 cytokines

Introduction

Adoptive transfer of Bispecific antibody Armed T cells (BATs) shows promising anti-tumor activity in solid tumors [1–4]. Our current strategy targets tumor cells using activated T cells (ATC) armed with bispecific antibodies (BiAb), of which one antibody binds to T cells and a second antibody binds to the tumor antigen on the tumor cells. The cytotoxic activity occurs upon engagement of ATC with tumor cells via the bispecific antibody bridge that stimulates BATs to release the lytic/cytotoxic molecules (perforins/granzymes) and various cytokines, chemokines, and signaling molecules extracellularly [5]. We have shown that in the presence of fresh PBMC, the BATs engaging tumor leads to in vitro “primary immunization” of naïve T cells and B cells against tumor cells [6, 7]. In patients with breast cancer and prostate cancer there is evidence that BATs induce endogenous immune responses that may be associated with improved overall survival [1, 3]. We hypothesized that the release of BATs Induced Tumor-Targeting Effectors (TITE) may serve as a potent anti-tumor and immune-activating immunotherapeutic strategy. In addition, TITE may contain damage-associated molecular patterns released from cancer cells, as a function of BATs mediated killing of tumor cells, likely to promote maturation of dendritic cells and cross-priming of cytotoxic T cells [8].

In a 3D Matrigel tumorsphere model, TITE induced high cytotoxic activity against a variety of tumor cells and promoted activation and proliferation of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME). The therapeutic advantages of using the key components of the TITE at low concentrations that recapitulates its activities (master mix of IFN-γ, TNF-α and MIP-1β) are manifold: (1) eliminates the preparation and waiting time for activation and expansion of a patient’s T cells before the treatment initiation; (2) master mix can serve as a ready off-the-shelf product; and (3) it is highly cost effective compared to cellular therapy. We speculate that using active components of TITE packaged in targeted nano particles will be effective not only by targeting “tumor” and altering the “TME,” but also by overcoming the challenges of tumor heterogeneity and immune tolerance by modulating the tumor infiltrating suppressor cells of the TME. Most therapeutic approaches are based on targeting tumor cells or a single component of the tumor-supporting microenvironment that eventually results in cancer recurrence. The master mix of the key components of TITE would have a broad impact by simultaneously targeting tumor cells and multiple components of the tumor-supporting factors, while supporting anti-tumor immune responses that may become self-sustained.

Methods

Cell lines

The human breast cancer cell lines [MDA-MB-231 (MB231), BT-20, SK-BR-3 (SKBR3), MCF-7], pancreatic and colon cancer cell lines (MiaPaCa-2, COLO-356, L3.6, PANC-1, HCT8), lung cancer cell lines (H292, A549, H460), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines (HN6, HN12) and epidermoid carcinoma cell line (A431) were obtained from ATCC and were maintained in DMEM culture media (Lonza Inc., Allendale, NJ) supplemented with 10% FBS (Lonza Inc.), 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 µg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen).

Production of bispecific antibodies

Bispecific antibodies (BiAbs) were produced by chemical heteroconjugation of OKT3 and Erbitux (a chimeric anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (anti-EGFR) IgG1, ImClone LLC., Branchburg, NJ) or OKT3 and Herceptin (a humanized anti-HER2 IgG1, Genentech Inc., South San Francisco, CA) using Sulpho-SMCC and Traut’s reagents as described previously [5]. We used anti-HER2 and anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies to make bispecific antibodies for this study because in our clinical studies, we use FDA approved monoclonal antibodies to make bispecific antibodies and since anti-HER2 (trastuzumab) and anti-EGFR (cetuximab) monoclonal antibodies are FDA approved we used these two monoclonal antibodies to produce bispecific antibodies. Secondly, most of the tumor types express at least one or both HER2 and EGFR antigens that enables us to target multiple tumor types using HER2- and EGFR-based bispecific antibodies. The expression of HER2 and EGFR on key cell lines used in this study are shown in Fig. 1d (Right panel).

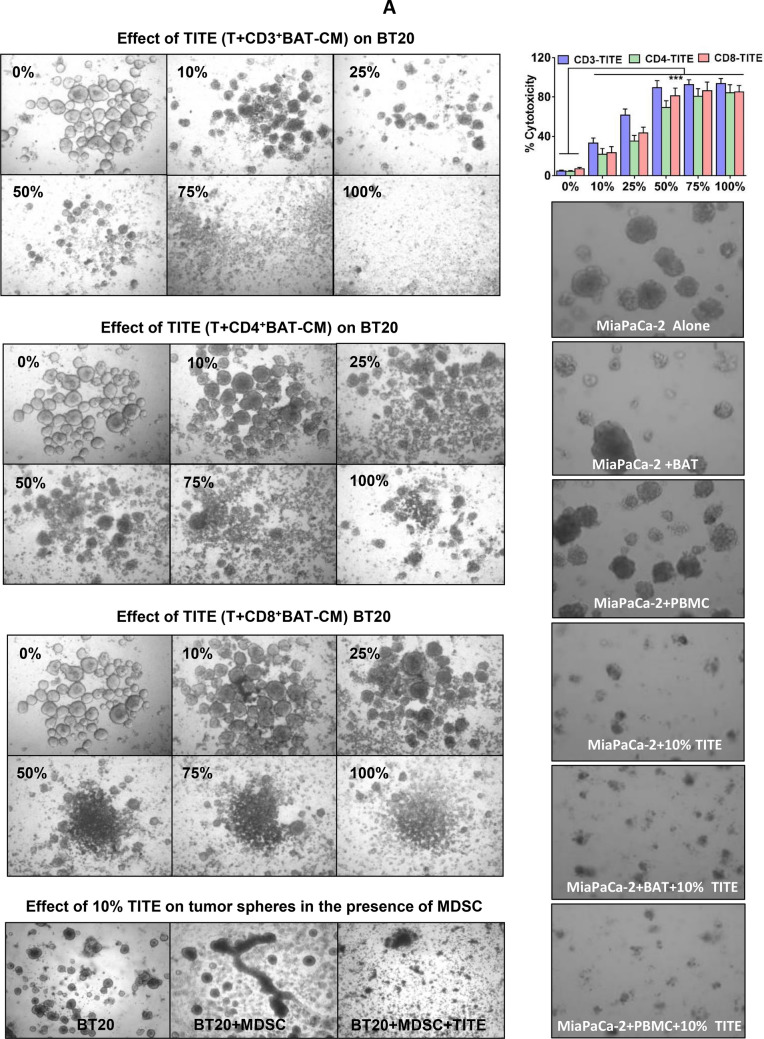

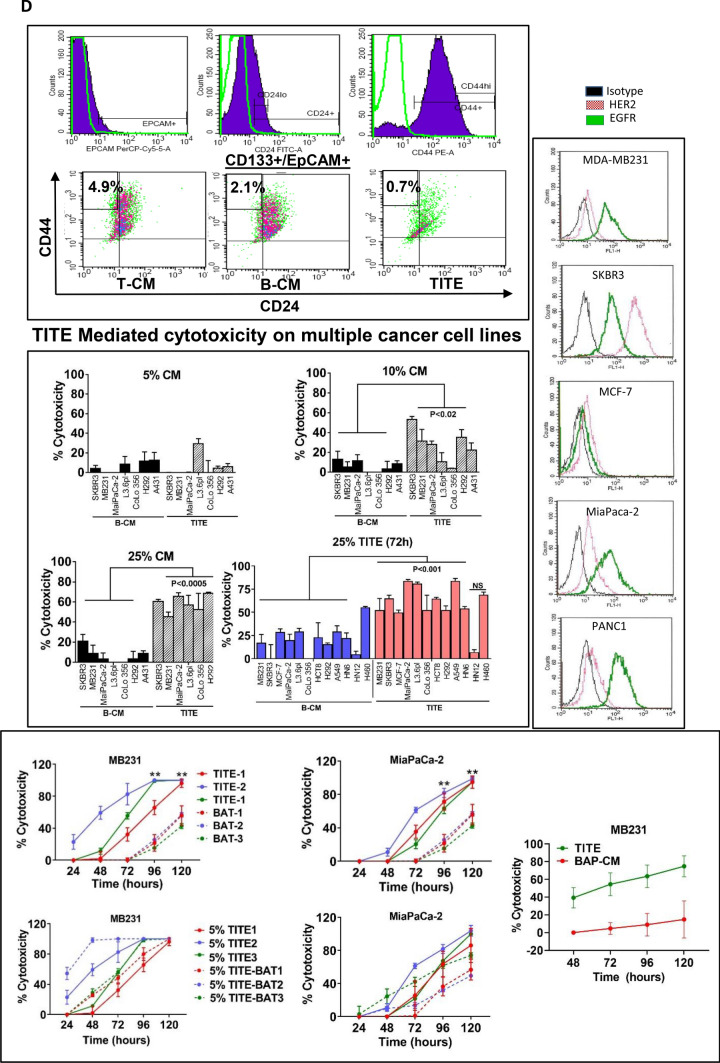

Fig. 1.

a Effect of TITE on BT20 and MiaPaCa-2 cells. Representative images show cytotoxic activity at indicated dose levels (0–100%) of TITE against BT20 tumorspheres in 3D cultures after 5 days. TITE was prepared from CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T cell sub-populations: 1st left panel shows the cytotoxic activity of TITE prepared from CD3+ BATs + tumor, 2nd and 3rd left panel show the cytotoxic activity of TITE prepared from CD4+ BATs + Tumor, and CD8+ BATs + Tumor. The TITE prepared from unfractionated activated T cells (CD3+ cells) showed superior killing of tumorspheres (1st panel) compared to the TITE prepared from CD4+ or CD8+ T cell fractions; Bottom left panel shows the cytotoxicity against BT20 tumorspheres co-cultured with MDSC in the presence or absence of 25% TITE. Top right panel shows the cytotoxic activity of CD3-TITE, CD4-TITE and CD8-TITE at indicated dose levels; cytotoxic activity was highly significant (p < 0.0001; n = 6) at all dose levels compared to cultures without TITE (0%). Bottom right panel shows the cytotoxic activity against MiaPaCa-2 tumorspheres co-cultured with BATs or PBMC (at E/T 1:1) in the presence or absence of TITE for 5 days; incubation with 10% TITE shows noticeably higher cytotoxicity compared to MiaPaCa-2 + PBMC or MiaPaCa-2 + BATs without TITE. BATs bispecific antibody-armed T cells, TITE BAT cell induced tumor-targeting effectors, E/T effector to target ratio. b Confocal images of MB231 cells or Lymphocytic endothelial cells (LECs) incubated with TITE. Representative confocal imaging shows growth inhibition of MB231 cells in 3D cultures in the presence of TITE compared to untreated control, T-CM or B-CM treated cells (Left panel); MB231 cells were plated on top of Cultrex (n = 5). Middle Panel shows top and side views of lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC)-tert, TITE shows enhanced nodal proliferation of LEC-tert. LEC-tert cells were plated on top of Cultrex, one grid represents 243.15 mm. Right panel shows that total volume of LEC-tert was increased significantly as indicated in the presence of TITE and B-CM compared to T-CM or untreated controls. c MB231 and Lymphocytic endothelial cells (LEC-tert) co-cultured with conditioned media show noticeably reduced growth of MB231 (red) and larger nodal junctions of LEC-tert (green) in a co-culture setting of MB231 and LEC-tert embedded into Cultrex, which is consistent with the observation when each is grown separately with TITE, suggesting a differential cell specific effect of TITE. One grid represents 243.15 mm. Top right panel shows enhanced proliferation of BATs when co-cultured with breast cancer cells (MB231) in the presence of TITE. Bottom right panel shows that cytotoxic activity is retain by soluble factor(s) with molecular weights between 10 and 50 kDa. d TITE Mediated cytotoxicity on multiple cancer cell lines. Top right panel shows the proportion of CD133+/ EpCAM+/CD44hi/CD24lo CSC were reduced to 0.7% in the presence of TITE compared to 4.9% in control culture without TITE or cultures containing B-CM (2.1%). Middle right panel shows the effect of TITE on multiple solid tumor cell lines at 5, 10 and 25% concentration. These findings were further confirmed in a larger panel of cancer cell lines (colored graph). At 10% and 25% concentration of TITE, highly significant cytotoxicity (p < 0.05 to p < 0.0005) was observed against MB231, MCF-7, SKBR3, MiaPaCa-2, L3.6pl, CoLo-356, HCT8, H292, A549, HN6 compared to B-CM at 72 h (n = 12). Left panel shows the relative expression of HER2 and EGFR in three breast cancer and two pancreatic cancer cell lines using anti-HER2 and anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies by flow cytometry. Bottom panel shows the cytotoxicity by TITE and BATs against breast and pancreatic cancer cell lines (top graphs) using Real Time Cell Analysis (RTCA). Lower two graphs show enhanced cytotoxicity against MB231 and MiaPaCa-2 cells by BATs over 120 h after priming with TITE (n = 3). Far right graph shows the cytotoxicity at 25% concentration of TITE or BiAb Armed PBMC-CM (BAP-CM) against breast cell line MDA MB-231 at 48–120 h using Real Time Cell Analysis (RTCA)

Expansion, generation and arming of activated T cells (ATC)

T cells from PBMC were activated with 20 ng/ml of OKT3 and expanded in 100 IU/ml of IL-2 for 14 days in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS as previously described [3]. Harvested ATC were armed with bispecific antibody [anti-CD3 × anti-HER2 (HER2Bi) or anti-CD3 × anti-EGFR (EGFRBi)] at a pre-optimized concentration of 50 ng/106 ATC as previously described [5].

Generation of conditioned media

The TITE was prepared by overnight culture of 1 × 106 tumor cells (T) and 25 × 106 of HER2 BATs, EGFR BATs or BiAb Armed PBMC-CM (BAP-CM) [25:1 effector to target (E/T) ratio] in 5 ml RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2% human serum followed by collecting and centrifuging the culture supernatant to remove cells and cellular debris. Control CMs were prepared using 1 × 106 tumor cells (T-CM) in 5 ml DMEM media supplemented with 2% human serum or 25 × 106 HER2 BATs, EGFR BATs (B-CM) or PBMC (P-CM) in 5 ml RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 2% human serum. The TITE was prepared and tested from at least 10 to 12 normal donor BATs. TITE was either tested individually or, in some experiments, TITE was pooled from 3 to 5 donors. For animal studies, TITE was concentrated 10× using 3 kDa cut-off Millipore centrifugal devices. TITE was either used fresh or frozen at − 70 °C for later use up to 1 year; therefore, once TITE is prepared and stored appropriately, it is ready to be used as an off-the-shelf product.

3D culture in matrigel

Typically tumor cells were adjusted to a concentration of 5000 cells/ml in DMEM culture media and overlaid on a solidified layer of Matrigel as described previously [9, 10]. Briefly, wells were coated with 100% Matrigel in 0.25-ml aliquots in 24-well plates and allowed to solidify by incubating at 37 °C for 30 min. Cancer cells were then seeded onto the Matrigel base as a single-cell suspension in the medium containing 2% Matrigel. Once tumorspheres were formed (5–7 days), PBMC or MDSC were added at 10:1 ratio (10 PBMC to 1 tumor cell) and cultured for an additional 5–7 days in the presence or absence of TITE, B-CM, T-CM and in a regular culture medium DMEM with 10% FBS.

Live confocal imaging of MB231 tumor cells and lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC)-tert in 3D cultures

For confocal imaging, MB231 breast cancer cells and LEC-tert (kind gift from Dr. Marion Groeger, University of Vienna Medical School, Austria) were labeled with CellTracker Green or Orange fluorescent dye at a final concentration of 5 µM for 45 min at 37 °C in the incubator, followed by washing and additional incubation with culture media for 30 min as per manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then cultured onto the Cultrex® Basement Membrane Extract (BME) on glass cover slips in the presence or absence of TITE (33%) for 4 days followed by confocal imaging to see the effect of TITE on breast cancer cells and/or LEC-tert cells. Cells were imaged live on a Zeiss 780 LSM confocal microscope using a 20 × water-immersion objective. Z-stacks through entire structures were captured for 16 contiguous fields in at least three separate experiments. The images were reconstructed in 3D and are represented here as either extended depth of focus images (en face view) or volume rendered 3D images tilted at a 45° angle using Volocity software.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxic activity of TITE against tumorspheres on Matrigel was measured by MTT, and cytotoxicity of TITE against multiple adherent tumor cells in 2D culture was assessed by 51Cr release assay as previously described [7]. For MTT, at the end of the incubation, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was added (40 µL/well of 5 mg/mL MTT in PBS in 96-well plate or 200 µL/well in 24-well plate) to each well and incubated in the dark for 3 h at 37 °C. After removal of the medium, the dye crystals formed in viable cells were dissolved in isopropanol (or SDS for 3D cultures) and detected by reading the absorption at 595 nm in the Tecan Ultra plate reader. Experiments were repeated three times in quadruplicate wells to ensure reproducibility.

Real time monitoring of cytotoxicity by xCELLigence system

In the Real Time Cell Analysis (RTCA) system, proliferation or cytotoxicity is measured by cellular impedance readout as Cell Index (CI) to monitor real-time changes in cell number. This is derived from the relative impedance changes corresponding to cellular coverage of the electrode sensors, normalized to baseline impedance values with medium only. Cell attachment was monitored using the RTCA software until the plateau phase was reached, which was usually after approximately 22–24 h before adding effector cells or TITE. We used breast (MB231, MCF-7) and pancreatic (MiaPaCa-2) cancer cell lines for xCELLigence RTCA as targets and TITE or BATs as effectors. The target cells (10–20,000 cells/well as optimized for each cell line) were plated in 96-well E-Plates followed by adding either 5% TITE alone or 5% TITE to prime tumor cells for 24 h before adding BATs at 2:1 E/T ratio. The target cell impedance signal was monitored for 120 h. Untreated targets or effectors without targets served as controls. To analyze the acquired data, CI values were exported and percentage of lysis was calculated in relation to the control cells lacking any effector cells.

Effect of TITE on immune cells

We assessed by flow cytometry the effect of TITE on the phenotype of immune cells, immune cell activation (PBMC), and immune suppressor cells (MDSC, Tregs) when co-cultured in 3D Matrigel with tumor cells for 3 days. For phenotypic changes, non-adherent cells were collected; Matrigel was digested using dispase to collect tumor cells, tumor associated MDSC, or other cells; and washed with FACS buffer (0.2% BSA in PBS). Cells collected prior to digestion were pooled with matrigel digested single-cell suspension before staining. Cells were stained for 30 min on ice with mixtures of fluorescently conjugated mAbs or isotype-matched controls, washed twice with FACS buffer, and analyzed. Antibodies used for staining include: anti-CD45, -CD3, -CD4, -CD8, -CD69, -41BB, -ICOS, -OX40, -PD1, -CD152, -CD11b, -CD14, -CD15, -CD33, -HLA-DR, -CD133, -CD44, -CD24, -EpCAM, -CD56, -CD19, -CD20, -CD80, -CD86 (BD Biosciences San Jose, CA). Cells were analyzed on a FACScalibur (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (BD Biosciences). T cell activation was analyzed by CD69+, CD4, and CD8 T cells; co-stimulatory receptor expression by gating on 41BB/ICOS/OX40 on CD45+/CD3+/CD4+ or CD45+/CD3+/CD8+ T cells; and co-inhibitory receptor expression by gating on CD152/PD-1 on CD45+/CD3+/CD4+ or CD45+/CD3+/CD8+ T cells. For MDSC, cells were gated on CD11b+/CD33+ population and analyzed for CD14+/HLA-DR− and CD15+/HLA-DR− expression. For mature APC, cells were gated on CD14− population and analyzed for CD80+/CD86+ cells. Cancer stem-like cells (CSC) were gated on EpCAM+/CD133+ population and analyzed for CD44hi/CD24lo/− among MB-231 cells.

Isolation of cancer stem-like cells

CD133+ cells were isolated using magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). CD133+ sorted cancer stem-like cells (CSC) from breast cancer cell line MB231 were expanded in ultra-low adherence plates at 1000 cells/ml concentration using serum-free DMEM/F12 supplemented with 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 20 ng/ml human recombinant epidermal growth factor (hrEGF), 10 ng/ml human recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor (hrbFGF), 2% B27 supplement without vitamin A, and 1% N2 supplement (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). More than 5% of cells showed CSC phenotype using flow cytometry by gating CD133+/EpCAM+/CD44hi/CD24lo/− cells in breast cancer cell lines. After 5 days, tumor clusters were cultured in the presence or absence of 25% TITE for 7 days, followed by staining for EpCAM, CD44 and CD24. Cells were gated on EpCAM+/CD133+ cells and analyzed for the CD44hi and CD24lo CSC population.

MDSC generation

We used anti-CD33 magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) to isolate CD33+ cells from co-cultures as previously described [9]. The CD33+ cells were cultured in the presence of 10 ng/ml GM-CSF and 10 ng/ml IL-6 for 7 days, media and cytokines were replaced every 2–3 days, and purity of cytokine stimulated MDSC was checked by flow cytometry for granulocytic and monocytic MDSC populations. The purity of isolated cell populations was found to be ~ 90% by flow cytometry.

Analysis of conditioned media

Size-based separation of conditioned media for functional analysis

TITE was fractionated using different molecular weight cut-off membranes. Small < 10 kDa, medium < 50 kDa, and large > 50 kDa molecular weight proteins were separated by Millipore filtration device. A < 3 kDa membrane was used to remove all proteins. RNase and DNase digestion were used as RNA/DNA-free TITE, and heat-treated TITE was used as protein-, RNA-, and DNA-free TITE. Fractionated TITE was used to narrow down the effector protein pool for functional protein analysis.

Cytokine profiling of conditioned media

Cytokines were quantified in culture supernatants collected from multiple donors’ BATs and multiple tumor cell lines in various culture conditions: tumor cells (MB-231, SKBR3, MiaPaCa-2, PANC-1) alone (T-CM), BATs alone (B-CM), tumor + BATs overnight co-cultures (TITE) using a 45-plex human cytokine Bio-Plex Array (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) on a Luminex system (Bio-Rad Lab., Hercules, CA) as previously described [7, 9]. The limit of detection for these assays is < 10 pg/ml based on detectable signal of > twofold above background (Bio-Rad). Cytokine concentrations were automatically calculated by the BioPlex Manager Software (Bio-Rad).

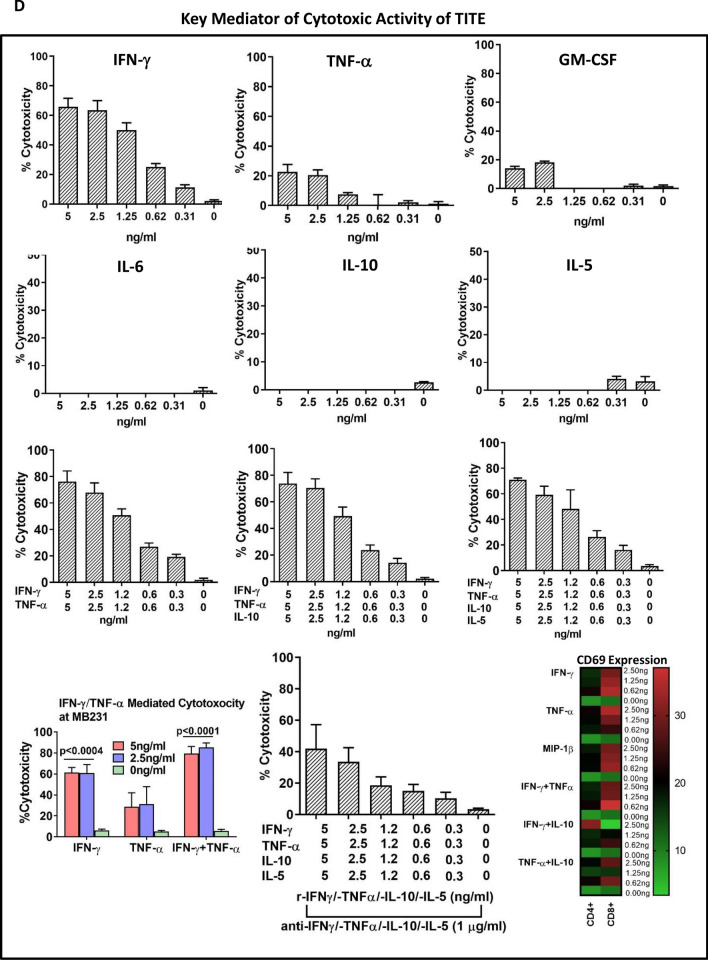

Evaluation of key components of TITE for anti-tumor and T cell stimulatory activity

We tested the key cytokines individually or in combination for their cytotoxic activity against tumor targets as well as their T cell stimulatory activity. The dose titration of IFN-γ, TNF-α, GM-CSF, IL-5, IL-6 and IL-10 ranged from 0 to 5 ng/ml for cytotoxicity. The cytotoxic effect of the combination was tested for the optimal dose(s) by MTT assay at 72 h against MB231 cells.We used 200 × concentrations of neutralizing antibodies to each recombinant cytokines/chemokines. The T cell activation was tested by detecting CD69 expression by flow cytometry after T cells (1 × 106 cells) were incubated for 24 h with IFN-γ, TNF-α, MIP-1β, IL-5 and IL-10 individually or with combination of IFN-γ + TNF-α and IFN-γ + IL-10 and TNF-α + IL-10 at concentrations ranging from 0, 0.62, 1.25 and 2.5 ng/ml. After 24 h incubation with cytokines/chemokines, T cells were washed 2 ×, resuspended in 100 μl flow staining buffer and incubated with Fc-blocker for 10 min followed by adding of anti-CD69-PE antibody for additional 20 min incubation. T cells were then washed 2 × and analyzed for CD69 expression by flow cytometry.

Phosphorylation-specific protein microarray of TITE

Phosphorylation-specific antibody microarrays (Fullmoon Biosystems) were used to see the pattern of up- and down-regulated proteins in T-CM, B-CM and TITE collected after 1 h of culture. The protein array consisted of 120 signaling pathway phospho-specific antibodies. The array layout consisted of antibodies against phosphorylated- and unphosphorylated-proteins, each replicated six times; actin and GAPDH served as controls. In brief, proteins were labeled with biotin and placed on pre-blocked microarray slides. After washing, detection of total and phosphorylated proteins was performed using Cy3-conjugated streptavidin. Expression of phosphorylated proteins was normalized to corresponding total protein expression from the intensity values obtained. Fold change represents the ratio of phosphorylation in T-CM, B-CM or TITE. Where indicated, protein phosphorylation data were confirmed by Western blot analysis.

Exosomal microRNA isolation from TITE, RT-PCR, real-time PCR and miScript miRNA PCR array

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) from TITE were isolated using Novak culture supernatant miRNA extraction kit (Novak, Canada). Reverse transcription (RT) was performed using the RT primers for each individual miRNA (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed using a miRVana qRT-PCR kit and PCR primers (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Human Inflammatory Response miRNA PCR Array: MIHS-105Z miScript miRNA PCR Array was done by Quigen.

Subcutaneous breast cancer ICR/Scid xenograft model

All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee of Wayne State University and the University of Virginia. Eight- to ten-week-old female ICR/Scid mice were injected subcutaneously (subQ) with MDA-MB-231 (5 × 106 cells/mouse) into the left flank. Tumor volume was measured twice a week with a caliper and calculated using the formula: A × B2/2, where A = length of tumor and B = width of tumor. Mice received 20 × 106 HER2Bi armed ATC (HER2 BATs), or received 150 µl 10 × TITE either IV or intra-tumorally (IT). The control group received PBS IV or IT 3 times a week for 2 weeks. At the end of 2 weeks, mice were sacrificed and tumors were harvested for histopathological analyses and immunohistochemistry for macrophage and granulocyte infiltration.

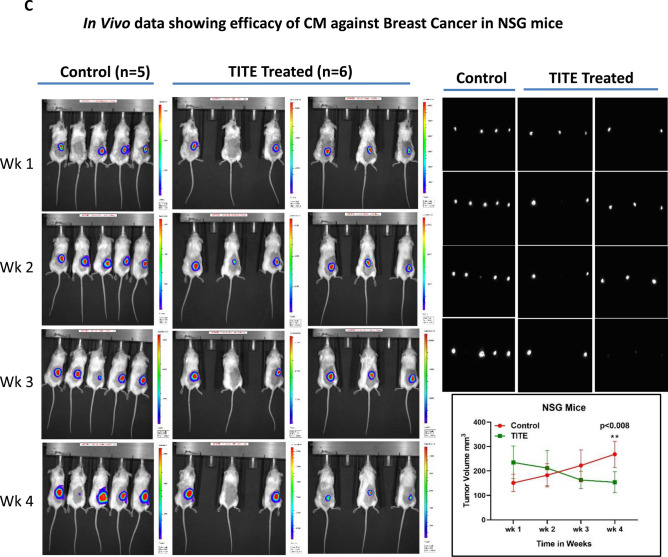

Subcutaneous breast cancer NSG xenograft model

We further confirmed the results observed in ICR-scid mice in 8–10-week-old female NOD scid gamma (NSG) mice (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (Jackson Laboratory), these mice have deficiency in innate immunity and deficiency in IL2 receptor gamma chain that disables cytokine signaling, lack mature T cells, B cells, and functional NK cells. Briefly, NSG mice were subcutaneously injected with 5 × 106 luciferase expressing MDA-MB-231cells into the left flank of each mouse. Once tumors become palpable, mice either received 150 µl 10 × TITE-IV or 150 µl PBS IV (control group) 3 times a week for 4 weeks. In vivo bioluminescence was measured by IVIS imaging for each group to monitor the tumor burden and tumor volume was measured twice a week with a caliper. At the end of 4 weeks, mice were sacrificed and tumors were harvested for histopathological analyses and immunohistochemistry for macrophage and granulocyte infiltration. All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee of Wayne State University and the University of Virginia.

In vivo injections of IFN-γ and TNF-α

Two key components of TITE that induce cytotoxicity against wide range of cancer cells were tested for in vivo toxicity in 8 to 10-week-old female ICR/scid mice. Mice were injected with either individually TNF-α and IFN-γ or combined TNF-α + IFN-γ via IV injection 3 × for 1 week to see their toxic effects in mice (n = 5). Doses were adjusted to the amounts equivalent to TITE per injection (150 μl of 10 × TITE). The average concentration of IFN-γ is ~ 2000 pg/ml and TNF-α is ~ 3000 pg/ml, we calculated the amount of IFN-γ and TNF-α present in 150 μl of 10 × TITE (IFN-γ = 2000 pg/ml and TNF-α = 3000 pg/ml, 10 × would be 20,000 pg = 20 ng/ml and 30,000 pg = 30 ng/ml, respectively, 150 μl would contain 3 ng IFN-γ and 4.5 ng of TNF-α. There were no signs of toxicity with IFN-γ, TNF-α or comination of both cytokines.

Collection of tissue samples from mice

The tumor, spleen, liver, heart and lungs were collected and washed in PBS. Tumors were cut into two pieces. One part of the tumor was minced into small pieces and incubated in enzyme cocktail (Miltenyi Biotec) followed by cell dissociation using a Miltenyi tissue dissociator. Dissociated cells were passed through a cell strainer and washed three times in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, gentamicin, and l-glutamine (complete media). The second part of the tumor was fixed in buffered formalin followed by paraffin embedding, sectioning, and staining. Spleens were homogenized through mincing and passing through a cell strainer to achieve single-cell suspensions. Red blood cells were lysed using ACK Lysis Buffer (Cambrex/BioWhittaker). Liver, heart, and lungs were analyzed for toxicity.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are presented as the mean of at least three or more independent experiments ± standard deviation. To determine whether there were statistically significant differences among different conditions within each experiment we used either one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests. Differences between groups were tested via an unpaired, two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. For each test, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

TITE inhibits tumorspheres in 3D cultures

Earlier, we showed that exogenous Th1 cytokines added to the 3D tumor culture sharply inhibited tumorsphere formation in Matrigel [7, 9]. Since Th1 cytokines are released during BATs mediated killing of tumor cells, in this study we investigated whether Th1 cytokine enriched secretome from tumor + BATs co-culture (released cytokines/chemokines/growth factors and other mediators in TITE) can inhibit growth of tumorspheres. We used TITE prepared from T cell sub-populations: (1) CD3+ T cells, (2) CD4+ T cells, and (3) CD8+ T cells armed with HER2Bi and co-cultured with tumor cells (MB231) for 24 h. The breast cancer cell lines BT20 and MB231 and pancreatic cancer cell line MiaPaCa-2 were cultured in the presence or absence of various percentages of TITE (0–100%) for 5 days, followed by imaging and MTT assay to determine the % viable cells in 3D culture. Figure 1a (left top to bottom panels) shows the microscopic images of tumorspheres incubated with TITE prepared from T cell subsets (top panel, CD3+ T cells; 2nd panel, CD4+ T cells; and 3rd panel, CD8+ T cells) for 72 h at indicated TITE concentrations. The TITE prepared from unfractionated activated T cells (CD3+ T cells) showed marked killing (top panel) of BT20 tumorspheres compared to the TITE generated from CD4+ or CD8+ T cell fractions (2nd and 3rd panels). Fourth panel shows TITE mediated disruption of tumorspheres in the presence of myeloid derived suppressor cells. Top graph of the right panel shows significantly increased cytotoxicity at all doses of CD3-, CD4- and CD8-TITE (p < 0.0001) compared to cultures without TITE. Similar observations were made for MiaPaCa-2 tumorspheres co-cultured with BATs or PBMC in the presence or absence of TITE; both size and number of tumorspheres were markedly reduced in the presence of TITE in all conditions (Fig. 1a, lower right panel).

Live confocal imaging of 3D cultures shows inhibition of MB231 tumors by TITE

There was a dramatic decrease in proliferation of MB231 cells in the presence of TITE from either single normal donor BATs, or pooled TITE prepared from three normal donor BATs, compared to control T-CM, B-CM and normal growth media. Representative data from TITE prepared from single normal donor BATs are shown in Fig. 1b, left panel.

TITE inreases nodal volume of lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC)-tert

Intriguingly, the TITE showed a completely reverse effect on LEC-tert by enhancing the proliferation and forming large nodal areas compared to control T-CM, B-CM and normal growth media. Figure 1b (middle panel) shows the top and side views from TITE and control CM treated LEC-tert. Right panel of Fig. 1b shows significantly increased LEC proliferation in the presence of TITE compared to T-CM (p < 0.0009), B-CM (p < 0.027) and normal growth media (p < 0.002).

TITE shows differential cell specific effect on MB231 and LEC-tert co-cultures

Furthermore, we examined whether TITE would show similar effects in co-culture of MB231 cells and LEC-tert as seen with individual cell type. Indeed TITE reduced proliferation of MB231 (CellTracker Orange fluorescent dye) and increased proliferation of LEC-tert (CellTracker Green fluorescent dye) as was observed with each cell type grown separately with TITE (Fig. 1c, left panel).

TITE induces proliferation of BATs in co-culture with MB231 cells

BATs were co-cultured with MB231 cells for 72 h at 10:1 ratio. The majority of tumor cells were killed in the culture. However, co-culture of BATs with MB231 cells in the presence of 5% TITE showed increased proliferation of BATs and fewer tumorspheres in z-stacked images as shown in the right top panel of Fig. 1c (mov file).

Activity of TITE is retained in > 10 kDa and < 50 kDa molecular weight fractions

Our results suggest that the soluble factor(s) between 10 and 50 kDa molecular weight retain cytotoxic activity against MB231 cells as shown in Fig. 1c (right bottom panel). Fractions below 3 kDa, < 10 kDa or heat-treated fractions (Denatured, DN) showed low to no cytotoxic activity. Since the functional activity was heat-sensitive, the factor(s) appeared to be protein. Similar to cytotoxic activity of soluble factor(s) between 10 and 50 kDa molecular weight, soluble factor(s) between 10 and 50 kDa also retained immune-activating activity.

TITE inhibits CSC in 3D suspension cultures

Results showed that in the presence of TITE, the proportion of CSC was reduced by 60–70% compared to control cultures without TITE (n = 5; p < 0.001). A similar significant difference was observed between cultures treated with TITE vs. B-CM (p < 0.05). Representative data in Fig. 1d, top panel show 0.7% CSC in TITE treated cultures compared to 4.9% in control cultures without TITE. Cultures containing B-CM also had reduced proportions of CD44hi/CD24lo CSC compared to control conditions (2.1% vs. 4.9%).

TITE exhibits cytotoxicity against multiple cancer cell lines “Universal tumor cell killer”

Further, we examined whether TITE would show similar effects as seen in 3D cultures for various tumor cell lines. First we determined the effect of various doses (5, 10 and 25%) of B-CM or TITE on tumor cells including SKBR3, MB231, MiaPaCa-2, L3.6pl, CoLo-356, A431 and H292 in 2D cultures (Fig. 1d, middle panel). At 5%, TITE mediated tumor lysis was very low to none. The cytotoxicity at 10% TITE ranged from 10 to 50% against various cell lines. The 25% TITE mediated cytotoxicity was consistently high across multiple cell lines at 72 h by MTT assay. We then confirmed the TITE mediated cytotoxicity in cell lines from various tumor types; consistent with our earlier results, 25% TITE showed highly significant cytotoxicity (p < 0.001 to p < 0.0005) against MB231, MCF-7, SKBR3, MiaPaCa-2, L3.6pl, CoLo-356, HCT8, H292, A549, and HN6 compared to B-CM at 72 h. One of the head and neck cell lines H460 showed high cytotoxicity by both B-CM and TITE, whereas HN12 showed no killing by either B-CM or TITE (Fig. 1d, middle panel). We also tested OKT3 × HER2 BiAb Armed PBMC-CM (BAP-CM) against MB231 cells that showed low cytotoxicity compared to TITE (~ 15% by BAP-CM vs. 80% by TITE) over 48–120 h (Fig. 1d, Far right graph in bottom panel).

TITE primed BATs exhibit enhanced cytotoxicity against tumor cells

Since 25% TITE was cytotoxic to various tumor targets, next we tested whether priming of BATs with TITE (24 h exposure with 5% TITE) could enhance BATs mediated cytotoxicity compared to unprimed BATs using continuous monitoring by Real Time Cell Analysis (RTCA). We used TITE prepared from the co-culture of MB231 cells + BATs from three normal donors (TITE1, TITE2, TITE3) tested against MB231 or pancreatic cancer cell line MiaPaCa-2. Cytotoxicity was twofold higher with 5% TITE (p < 0.005) compared to BATs (2:1 E/T ratio) from all three donors for both cell lines. Similarly, cytotoxicity by BATs (2:1 E/T ratio) increased against MiaPaCa-2 or MB231 cells after being primed with 5% TITE (p < 0.004) overnight compared to unprimed BATs against MiaPaCa-2 or MB231 (Fig. 1d, bottom panel, top two graphs).

TITE inhibits MDSC and tregs in 3D co-culture

Next, we examined the effect of TITE on myeloid derived suppressor cells and Tregs in the TME in 3D cultures compared to the effect of T-CM or B-CM. The phenotype of MDSC and Tregs in the co-culture with tumor spheroids was characterized by analyzing the expression of cell surface markers by flow cytometry. There was a significant reduction in CD33+/CD11b+/HLA-DR− MDSC (p < 0.004) and CD4+/CD25+/CD127− Treg populations (p < 0.003) in the presence of TITE compared to T-CM (Fig. 2a, right upper panel). There was no significant difference between TITE and B-CM for percent positive MDSC and Tregs.

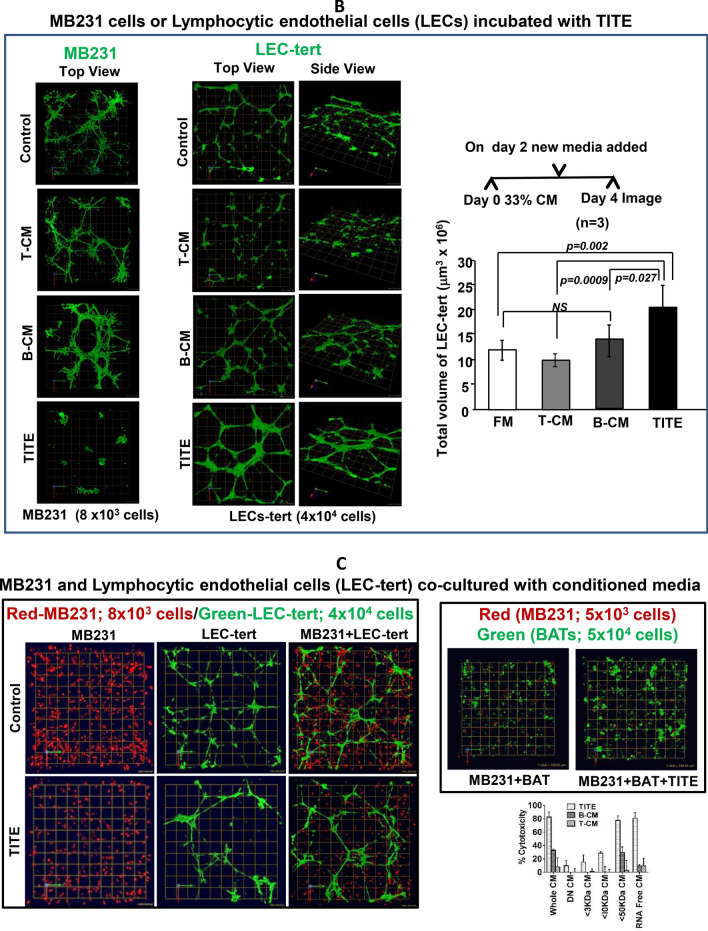

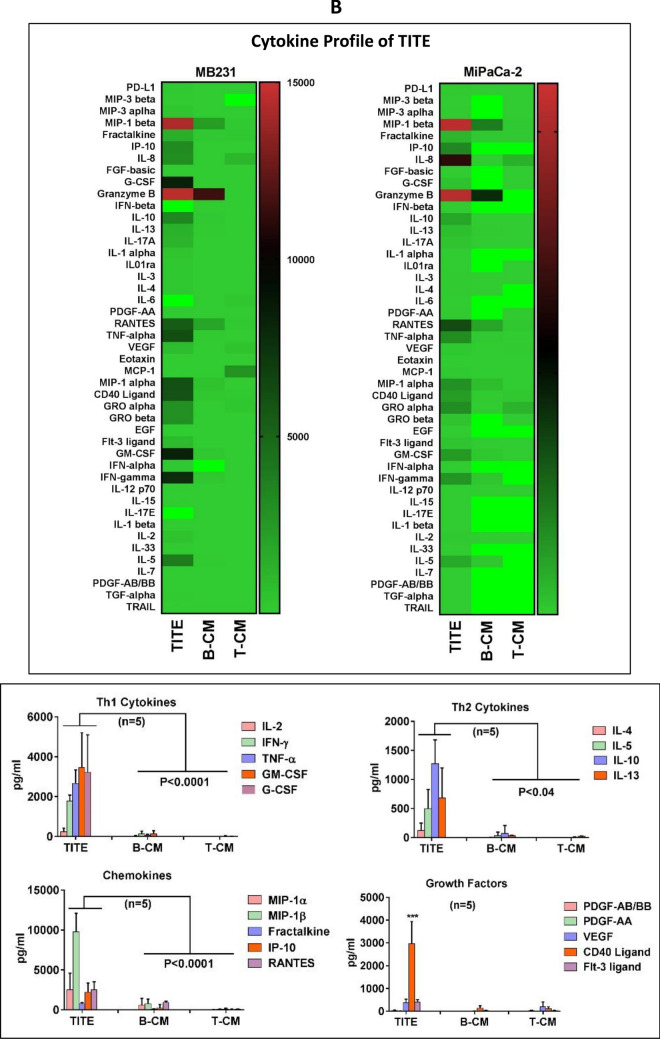

Fig. 2.

T cell Activation by TITE. Immune cell modulation by TITE. a Normal donor PBMC (n = 3) incubated with 10% B-CM or 10% TITE show significant activation of T cells (CD4+/CD69+, p < 0.0004 and CD8+/CD69+, p < 0.0001) compared to untreated PBMC (left panel). The top right panel shows that normal donor PBMC when incubated with MB231 tumor cells also show significantly activated CD4+/CD69+ and CD8+/CD69+ T cells in the presence of TITE (p < 0.0001) or B-CM (p < 0.005), and significant reduction in both CD33+/HLA-DR− MDSC (p < 0.004) and CD4+/CD25+/CD127lo Treg cells (p < 0.003) in the presence of TITE. Bottom Panel) Shows the expression of co-stimulatory (4-1BB, ICOS and OX40) or co-inhibitory (PD-1) markers on CD4+ (top panel) and CD8+ T cells (lower panel) in the co-cultures of PBMC with tumor cells either MB231 (left) or MCF-7 (right) for 48 h with various percentages of TITE (n = 3). Both co-stimulatory (4-1BB, ICOS and OX40) or co-inhibitory (PD-1) molecules showed significantly increased expression in the presence of all dose levels of TITE (MB231, p < 0.0002; MCF-7, p < 0.003 to p < 0.0002). b Cytokine Profile of TITE. Shows the quantitative cytokine profiles of TITE and control CM (T-CM and B-CM) using 45-panel Luminex multiplex technology (n = 5). Heat maps show the representative profiles of TITE, B-CM and T-CM. Left panel shows the profile of TITE prepared from MB231 + BATs, and right panel shows the heat map of TITE prepared from MiaPaCa-2 + BATs. Lower panel shows the quantitative data. TITE show the significant increase in Th1 cytokines (p < 0.0001), Th2 cytokines (p < 0.04), chemokines (p < 0.0001) and growth factor CD40L (p < 0.0001) compared to B-CM and T-CM; all values are presented as pg/ml. c. Cytokine Profile of TITE from Multiple Cell Lines. Shows individual Th1 cytokines, Th2 cytokines and chemokines levels as dot plots of TITEs prepared from five normal donor HER2 BATs and EGFR BATs co-cultured with four different cell lines, altogether representing 40 conditions for each cytokine. In all 40 conditions, Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α and GM-CSF) were significantly higher, p value ranging from p < 0.005 to p < 0.0002; consistently increased levels were also found for IL-10 (p < 0.05 to p < 0.0005) compared to B-CM. Similarly, the T cell recruiting chemokines showed significantly increased levels (p < 0.05 to p < 0.0005) across all cell lines and different TITEs compared to B-CM. d Key Mediator of Anti-Tumor and Immune Stimulating Activity of TITE. Representative data on dose titration for the cytotoxic effects of key cytokines individually or in combinations (IFN-γ, TNF-α, GM-CSF, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-6) is shown in top and two middle panels against MB231 cell line. Bottom panel shows significantly increased cytotoxicity by IFN-γ alone (p < 0.0004) or in combination with TNF-α (p < 0.0001) at 2.5 and 5 ng/ml concentrations compared to untreated control (0 ng/ml), middle graph of the bottom panel shows the effect of neutralizing antibodies to their corresponding cytokine on cytotoxicity. IL-6 and GM-CSF both showed no cytotoxic effects. The heat map shows the CD69 expression by flow cytometry following overnight incubation with IFN-γ, TNF-α, MIP-1β, IL-5 and IL-10 individually or combination of IFN-γ + TNF-α and IFN-γ + IL-10 and TNF-α, IL-10 at the indicated concentrations (d, bottom panel)

TITE induces activation of T cell subsets in 3D co-culture

We investigated the phenotypic changes in the T cells in the presence of TITE (n = 3) by evaluating expression of early activation marker CD69; immune-modulatory molecules 4-1BB, ICOS, and OX40. Early activation marker CD69 was up-regulated in T cells isolated from the co-culture with tumor cells, and the expression of CD69 was significantly higher on both CD4+ (p < 0.0004) and CD8+ T (p < 0.0001) cell sub-populations in the presence of TITE (Fig. 2a, left upper panel). A significant increase in the expression of the activating co-stimulatory molecules 4-1BB, ICOS, OX40 was observed: up to fivefold on CD4+ T cells and twofold on CD8+ T cells in the presence of MB231 cells (p < 0.0002) or MCF-7 cells (p < 0.003 to p < 0.0002) (Fig. 2a, lower panels). Taken together, our data show that TITE induced activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as reflected by increased expression of activation markers on T cells.

The cytokines/chemokines in TITE show dominant Th1 cytokine profile

Soluble factors including cytokines, chemokines and growth factors in supernatants from tumor alone (T-CM), BATs alone (B-CM) or tumor cells + BATs co-culture (TITE) were measured using the Luminex multiplex technology. Tumor cell lines MB231, SKBR3, MiaPaCa-2, and PANC-1 co-cultured with BATs secreted high levels of Th1 cytokines IFN-γ, TNF-α, GM-CSF and T cell recruiting chemokines IP-10, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES. Levels were moderate for Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13 and growth factors CD40L, VEGF and PDGF-AA in TITE compared to the levels of Th1 cytokines and chemokines in TITE. Heat maps of cytokine profiles of TITE prepared from MB231 and MiaPaCa-2 are shown in Fig. 2b (Top panel). Bottom panel shows significantly increased levels of Th1 cytokines (p < 0.0001), Th2 cytokine IL-10 (p < 0.04), chemokines (p < 0.0001) and growth factor CD40L (p < 0.0001) in TITE (prepared from MB231 + BATs) compared to B-CM or T-CM (n = 5). Figure 2c shows the multiplex data of TITE prepared from five normal donor HER2 BATs, five normal donor EGFR BATs and four different cells lines (MB231, SKBR3, MiaPaCa-2 and PANC-1) resulting in cytokines/chemokines/growth factor profiles of 40 different TITEs. Individual data for Th1, Th2 and chemokines are plotted as dot plots for each HER2- and EGFR BATs and the corresponding cell lines. All 40 TITEs show significantly higher levels of Th1 cytokines (p < 0.002 to p < 0.0001) and T cells recruiting and activating chemokines (p < 0.002 to p < 0.0001) compared to B-CM and T-CM.

IFN-γ, TNF-α and granzyme B mediated tumor cell killing

The TITE generated from the tumor/BATs co-culture showed significantly higher levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α and GZB compared to B-CM and T-CM. Top and middle panels show the dose titration of IFN-γ, TNF-α, GM-CSF, IL-5, IL-6 and IL-10 individually as well as in various combinations (Fig. 2d). Cytokines IL-5, IL-6 and IL-10 showed no killing at any dose level except by GM-CSF that showed some cytotoxic activity at 5 and 2.5 ng/ml dose level. IFN-γ showed ~ 60% cytotoxic activity at both 5 and 2.5 ng/ml concentrations (p < 0.0004), TNF-α showed 20–25% cytotoxicity, and combination of IFN-γ and TNF-α showed additive (~ 80%) cytotoxic effect (p < 0.0001) against MB231 cells (Fig. 2d, bottom panel). Combinations of Th2 cytokines (IL-5 and IL-10) with Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ and TNF-α) did not affect the cytotoxic activity of IFN-γ and TNF-α (Fig. 2d, 3rd panel), but addition of neutalizing antibodies to IFN-γ and TNF-α decreased the cytotoxic activities of IFN-γ and TNF-α (Fig. 2d, bottom panel). Similar cytotoxic activities were evident against MiaPaCa-2 cell line (data not shown).

GZB was present in very high levels in TITE; it is the most active member in the granzyme family, which activates initiator caspases (such as caspases-8, -9, -10) and then promotes apoptosis through directly processing effector caspases-3 and -7 to promote apoptosis [10, 11]. Since GZB has already been shown to have potent lytic activity and play a major role in T cell mediated cytotoxicity [10, 11], we did not test the cytotoxic activity of GZB.

IFN-γ, TNF-α and MIP-1β induce T cell activation

Since TITE contained dominant Th1 cytokines, we tested whether IFN-γ, TNF-α, MIP-1β cytokines induce T cell activation (judged by CD69 expression). All three cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, MIP-1β) induced T cell activation showing increased expression of CD69 by flow cytometry, while there were no changes observed in CD69 expression on T cells after 24 h incubation with IL-5 and IL-10 compared untreated control. Our combination data show that adding IL-10 to IFN-γ or TNF-α was able to suppress T cell activation at all doses. Data is presented in Fig. 2d (Bottom panel, right).

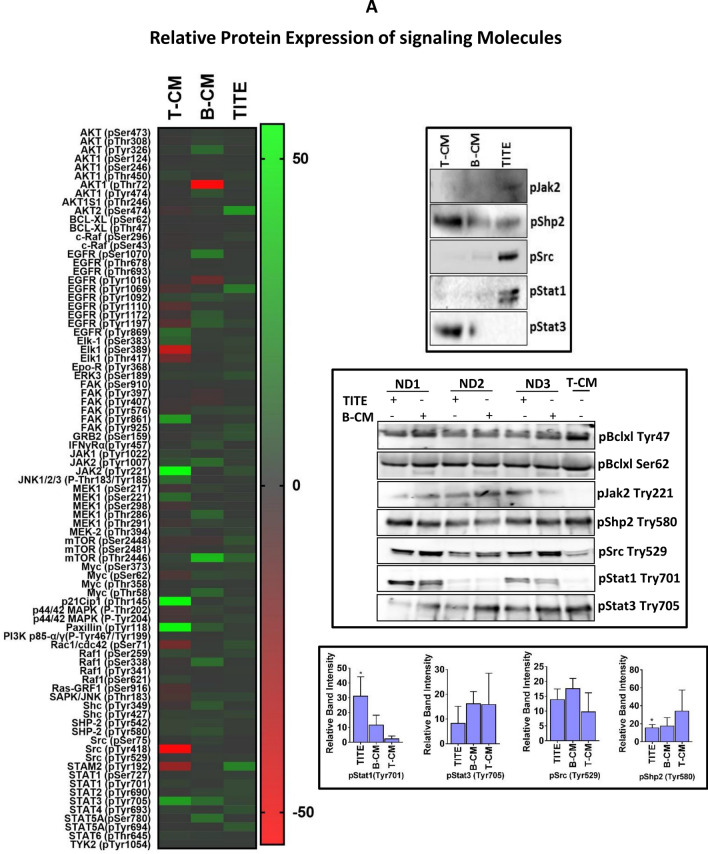

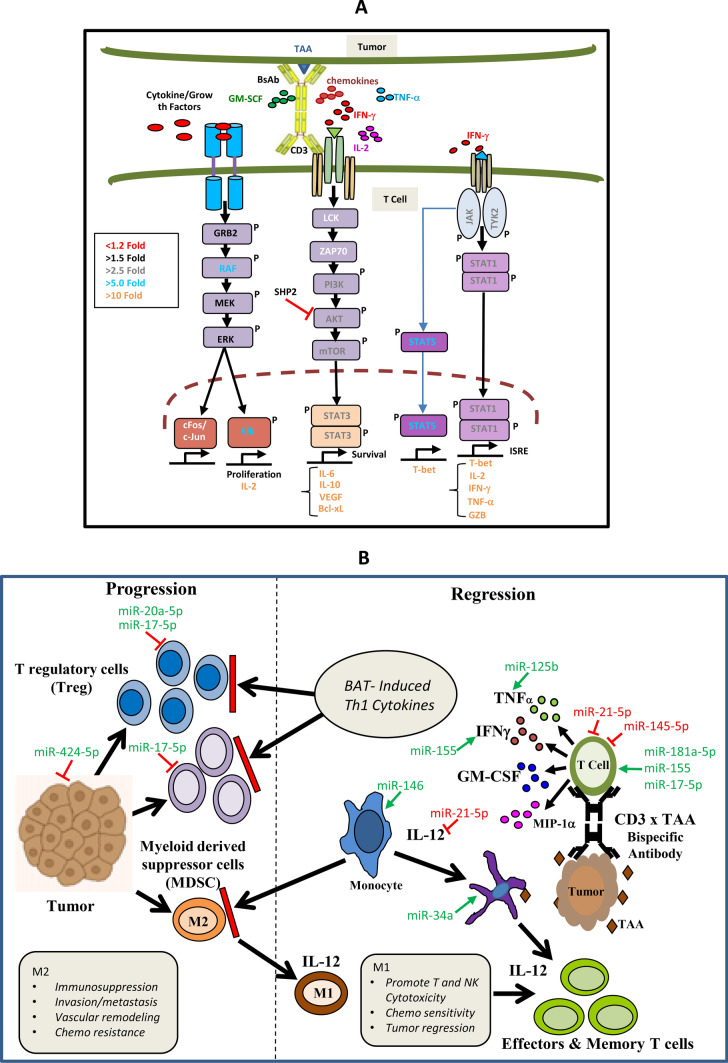

Phospho-specific protein array pattern indicates JAK/STAT1 signaling

In general our phospho-antibody array data showed differential release of signaling molecules in TITE compared to B-CM and T-CM. A relative fold expression of most of the released molecules in TITE supports immune activation and induction of Th1 cytokines (Fig. 3a). Released STAT family members showed increased levels of STAT1/STAT3/STAT5 in TITE and increased STAT3/STAT6 in B-CM and T-CM. Upper right panel shows the relative expression of selected signaling molecules (pJAK2, pSHP2, pSrc, pSTAT1 and pSTAT3) by western blot in the same TITE, B-CM and T-CM to corroborate the phospho-signaling array data as shown in the heat map. We further confirmed the pSTAT1 and pSTAT3 expression by western blot analysis in three new TITE, B-CM and T-CM (Middle right panel); the relative band intensities were significantly higher for pSTAT1 (p < 0.02; n = 3) and significantly lower for pSHP2 (p < 0.04; n = 3) in TITE compared to T-CM (Lower right panel). These data support that high levels of Th1 cytokines in TITE are induced by phospho-STAT1 (phosphorylation at Tyr701) signaling during BATs engagement to tumor cells. In T-CM, there was increased expression of phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705) and phospho-STAT6, but the difference was not statistically significant compared to B-CM or TITE.

Fig. 3.

Relative Protein Expression of Signaling Molecules. a Left panel shows the representative heat map of signaling array of TITE and controls (T-CM and B-CM), data is presented as relative fold-changes in TITE, T-CM and B-CM compared to internal control GAPDH. Top right panel shows the validation of selected phospho-signaling proteins by western blot of the same sample shown in the heat map. Middle right panel shows the western blot of selected phospho-signaling proteins in three different TITEs, B-CM and T-CM; Bottom right panel shows the measurement of relative band intensities; a significantly higher expression of pSTAT1 (tyr701) (p < 0.04) and significantly lower expression of pSHP-2 (tyr580) (p < 0.05) is displayed as asterisks. b Relative Expression of MicroRNA. The representative heat map (left panel) shows the normalized miRNA array data of TITE and control CMs (T-CM and B-CM). Right heat map shows an average fold-change in exosomal miRNA isolated from B-CM and TITE relative to T-CM prepared from three normal donor BATs and MB231 cell line. Lower right panel shows the fold regulation of some selected up- or down-regulated miRNAs in TITE and B-CM relative to T-CM. c Fold Change in miRNA. Shows the validation of miR-93, miR-155, miR-21, miR-let-7, miR-34a, miR-15a, miR-150 and miR-145a by qRT-PCR; data are presented as fold expression relative to T-CM

TITE shows immune-activating miRNA expression profile

To understand the role of miRNAs in the alteration of cellular and tumor microenvironment, exosomal RNAs from culture supernatants of various culture conditions using MB-231 cell line and BATs (T-CM, B-CM and TITE) were used for the miRNA profiling. The panel consisted of 84 miRNAs. There were 72 miRNAs that were differentially expressed (fold-change > 2 or < − 2, p < 0.05) in TITE (n = 3) or B-CM compared to T-CM (n = 3). There were 12 common miRNAs in all three groups. At the fold-change cut-off of 1.5, the miRNA array revealed 16/84 miRNAs significantly up-regulated and 56 down-regulated (Fig. 3b). The heat maps indicated the number of miRNAs that were differentially regulated in TITE and control CMs. Many miRNAs that were down-regulated in T-CM samples were mostly associated with pro-apoptotic pathways. Among the 72 miRNAs common to B-CM and TITE, approximately 19% (n = 16) were up-regulated and ~ 66% (n = 56) were down-regulated in both groups (Fig. 3b). Selected miRNAs (miR-21, miR-15, miR-34, miR-93 and miR-let-7) were validated by qRT-PCR. Representative qRT-PCR data of miR-93 and miR-let-7 show concordance with miRNA array data (Fig. 3c). Since three important immune related miRNAs (miR-155, miR-150 and miR-146) were not present in our 84-panel miRNA array, we did qRT-PCR for miR-155, miR-150, and miR-146 and found up-regulation of miR-155 and miR150, but down-regulation of miR-146 (Fig. 3c).

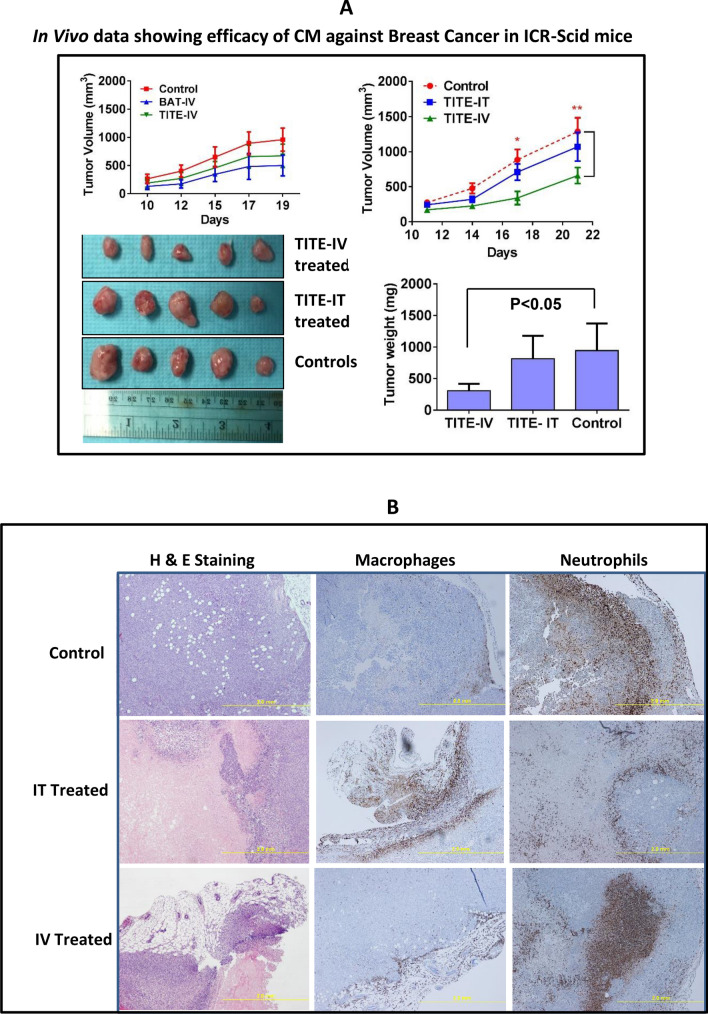

TITE treated mice show significantly reduced tumor growth

Since TITE containes high levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, we wanted to determine if TNF-α and IFN-γ can cause toxicity in mice when injected with similar concentrations present in the TITE. Five ICR-SCID mice (n = 5) who received 3 × intravenous injection of TNF-α, IFN-γ individually or in combination (equivalent to amounts present in TITE) for 1 week did not show any signs of toxicity, which led us to proceed with in vivo experiments using TITE. Next, MB-231 tumor cell line was injected into the flanks of ICR-SCID mice (n = 10/group). After tumors become palpable, tumor-bearing mice were split into three groups. Group 1 was treated with IV injections of BATs, group 2 was treated with IV injections of TITE, and group 3 with IV injections of vehicle 2 ×/week for 3 weeks. Tumor growth was delayed after 3 weeks in both BATs and TITE treated mice (Fig. 4a) compared to vehicle injected control mice. We then compared whether 3 × injection/week would show significant delay in tumor growth and whether the route of injection IV vs. intra-tumorally (IT) treated mice would show comparable tumor growth delay (n = 5). After tumors become palpable, mice were treated with TITE (IV vs. IT) 3 ×/week for 2–3 weeks. Tumor growth was significantly delayed (tumor size, p < 0.05; tumor volume p < 0.003) after 2 weeks when TITE was injected IV (Fig. 4a) compared to IT treated or control mice. No sign of toxicity was observed in heart, lung, liver or spleen in TITE treated mice examined by H&E staining of tissue sections (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

a In Vivo Data Showing Efficacy of CM Against Breast Cancer. The MB231 breast cancer cell line was injected into the flanks of ICR-SCID mice (n = 5/group), a representative data from one experiment is shown. Tumor-bearing mice were treated with IV injections of BATs, TITE and vehicle 2 ×/week for 3 weeks (top left). Top right, tumor-bearing mice treated with IV vs. IT injections of TITE and vehicle 3 ×/week for 3 weeks show significant delay in tumor volume (p < 0.003) as well as tumor size (p < 0.05) in lower right panel, a representative data from one experiment is shown (n = 6). Lower left panel shows the gross tumor appearance (scale bar = 1 inch). b H&E and IHC Staining of TITE Treated and Untreated Murine Tumors. Shows representative tumor sections from control mice, mice treated with TITE-intratumorally (IT) or mice treated with TITE-intravenously (IV) stained for myeloperoxidase (for granulocytes) and F4/80 (for macrophages). Representative H&E staining in xenograft tumors (scale bar = 2 mm) treated with TITE-IV, TITE-IT and vehicle-IV are shown in the left panel. Staining for macrophages and neutrophils are shown in the middle and right panels. c Both bioluminescence images of NSG mice (Left panel) and tumors (Right panel), show reduced tumor growth in TITE treated mice. Tumor measurements (Lower right panel) show significantly reduced (p < 0.008) in tumor volume in TITE treated mice after 4 weeks compared to vehicle injected control mice (control group, n = 5; TITE treated group, n = 6)

Staining of TITE treated tumors shows increased duct formation at the margins

Control, TITE-IT and TITE-IV treated tumor sections were stained for myeloperoxidase (for granulocytes) and F4/80 (for macrophages). Representative H&E staining in xenograft tumors (scale bar = 2 mm) shows that IV treated tumors exhibit duct formation at the margins and central necrotic regions in the IV treated mice. The IT treated tumors appear large in size but show large necrotic regions in the center, compared to solid centers in the control mice. Staining for macrophages appears to be at the margin for all control and treated tumors; however, granulocytes in IT treated tumors surround the tumor cell islands, while IV treated tumors show large focal infiltrations of granulocytes compared to the control tumors (Fig. 4b).

NSG mice show significant reduction in tumor growth after treatment with TITE

Bioluminescence images (BLI) of NSG mice (control group, n = 5; TITE treated group, n = 6) and tumors show tumor growth was reduced in TITE treated mice after 4 weeks (Fig. 4c, Left and Right panels) compared to vehicle injected control mice. Tumor volume was significantly reduced (p < 0.008) after 4 weeks in TITE injected mice (Fig. 4c, bottom right panel) compared to control mice. No sign of toxicity was observed in heart, lung, liver or spleen in TITE treated mice examined by H&E staining of tissue sections (data not shown).

Discussion

In vivo studies in ICR/scid and NSG mice injected with MDA-MB-231 cells showed significant reduction in tumor growth (ICR/scid mice p < 0.003; NSG mice p < 0.008) when treated 3 times/week with tumor/BATs-derived TITE for 3–4 weeks. Tumor burden was measured by both bioluminescence imaging and caliper based measurement of tumor volume. Interestingly, cytotoxicity by BATs (2:1 E/T ratio) increased against cancer cell lines after being primed with 5% TITE (p < 0.004) overnight compared to unprimed BATs against MiaPaCa-2 or MB231 suggesting that TITE is not only has direct effects on tumor growth but can also enhance immune cell functions.

The tumor/BATs-derived TITE initiates the paracrine signaling responsible for immune activation and anti-tumor activity through cytokines, chemokines and growth factors. The TITE, enriched in Th1 cytokine/chemokines, showed a significant destruction of tumorspheres (p < 0.0001) at the concentration of just 10% (TITE prepared from BATs and tumor cell co-culture at 25:1 ratio) with complete destruction at 50% concentration. These data confirm our earlier findings that exogenous Th1 cytokines remarkably altered the growth characteristics (inhibition of colony-forming ability) of tumorspheres in 3D Matrigel cultures [7, 9]. Similar killing of immune suppressive cell populations was observed by TITE when tumor cells were incubated with MDSC and/or Tregs. Moreover, TITE prepared from a single-cell line was cytotoxic against multiple cell lines from multiple tumor types. In contrast to its cytotoxic effects on tumor and immune suppressive cells, TITE induced nodal proliferation of LECs, as well as activation and proliferation of T cells, suggesting cell specific effects of TITE. There was a significant reduction in MDSC (p < 0.004) and Treg (p < 0.003) populations in the presence of TITE, and a significant increase in activation (CD69, p < 0.0004) and co-stimulatory molecules (4-1BB/ICOS/OX40, p < 0.003 to p < 0.0002) of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the presence of both MB231 and MCF-7 cells. These findings suggest that TITE mediated substantial cytotoxic activity against a variety of tumor cell lines, inhibited immune suppressor cells (Tregs and MDSC) in the tumor microenvironment, and promoted activation and proliferation of T cells and LECs. To understand the mechanism triggering release and being responsible for differential anti-tumor and immune-activating effects of TITE, we did multiplex cytokine/chemokine array, phospho-signaling array and miRNA array analyses.

The profile of cytokines/chemokines released in TITE from BATs interaction to tumor cells in a co-culture shows enrichment of Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, Granzyme B), T cell and monocyte recruiting chemokines (IP-10, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES), monocyte activating cytokines (GM-CSF, TNF-α, CD40L), and Th2 cytokines (IL-10, IL-5, and IL-13) compared to the levels of cytokine and chemokines in B-CM and T-CM. Cytokine profiling data suggest that TITE is enriched in key dual functioning cytokines [immune modulating cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, GM-CSF) and tumor killing cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, Granzyme B)]. Increased levels of Th2 cytokines may play important roles in controlling excessive inflammatory conditions.

Since TITE is comprised of the factors released as a function of tumor stimulated BATs either through activation-induced release or activation-induced cell death, our phospho-antibody array data revealed the prominent STAT signaling in activated BATs is mediated by STAT1 and STAT5. Both STAT1 and STAT5 are activated by a number of different ligands, including IFN-γ, EGF, PDGF and IL-6 by phosphorylation at both Tyr701 and Ser727 [12–14]. The phosphorylation of STAT1 at Tyr701/Ser727 induces STAT1 dimerization, nuclear translocation and DNA binding for transcriptional activity and biological function [15]. The release of Th1 cytokines appears to be through JAK/STAT1 signaling in BATs (Fig. 5a), whereas Th2 signaling is likely to be downstream of CD3 (via engagement with bispecific antibody) through PI3K/AKT/mTOR/STAT3 signaling [16]. TITE showed a significantly low level of SHP-2 (p < 0.04), a negative regulator of the JAK-STAT1 pathway [17] compared to T-CM, indicating reduced inhibition of JAK/STAT1 signaling. Since STAT3 and STAT6 are the critical signaling pathways in tumors induced by upstream regulators such as VEGF, EGF, PDGF, and IL-6 [18–22] and support tumor growth, lower levels of both upstream and downstream regulators of tumor-supporting signaling molecules in TITE further support the anti-tumor activity of TITE.

Fig. 5.

a Shows the proposed intracellular signalining by BATs + tumor cell generated TITE. b Shows the mechanism of action of TITE in TME immune modulation, anti-tumor activity and likely generation of in situ immunization at the cellular and humoral level through cytokines/chemokines and microRNA. TAA tumor associated antigen; TME tumor microenvironment. BATs bispecific antibody-armed T cells, TITE BAT cell induced tumor-targeting effectors

Our miRNA array data show that highly up-regulated miRNAs in TITE and B-CM (miR-16-5p, miR-17-5p, miR-195-5p, miR-20a-5p, miR-93-5p, miR-181a-5p, miR-181c-5p, miR-186-5p, miR-106a-5p) are associated with T cell function and activation and activation-induced cell death [16, 23–25]. Since some of the immune function related miRNAs were not present in the 84-miRNA panel, we performed qRT-PCR for miR-155, miR-150, miR-146a, and miR-34a (n = 5). Our data show that miR-150 and miR-146a were down-regulated in both B-CM and TITE, while miR-155 was highly up-regulated in TITE. The miR-155 and miR-146a act as positive and negative regulators of immune response [26]. Previous reports have shown miR-155 is associated with the activation of macrophages via TLR signaling to sustain M1-like TAM activation, whereas miR-146 represses M1 TAM [26]. The miR-155 expression has also been shown to regulate differentiation of T helper cells in favor of the Th1 phenotype and the maturation and activation of CTLs into effectors [27]. On the contrary, miR-130/301 and miR-146a (low in TITE) have displayed inhibiting effects on CTL immune responses [28]. Similar to immune response regulation, miRNAs play important roles in the regulation of tumor growth, invasion and metastasis. MiR-25-93-106b cluster has been shown to regulate both CXCL12 and PD-L1 in pancreatic cancer patients who are resistant to PD-1 inhibition [29]. The miR-17 (up-regulated in TITE) has been shown to inhibit invasion and metastasis of MB231 cells using conditioned medium from the miR-17/20-overexpressing MCF-7 cell line [30]. The miRs down-regulated in TITE (miR-125a/b, miR-146a, miR-150a, miR-21, miR-301a and miR-301b) have been shown to promote tumor growth and migration by targeting TGFBR2 to modulate TGF-β signaling pathway in colorectal carcinoma [31].

Cell based therapy, particularly CAR T cell therapy, offers a novel and potent therapeutic modality, but has shown limited activity in solid tumors. These limitations are due to their: (1) poor penetration into the solid mass, (2) loss of activity in immune suppressive TME, and (3) “off tumor on target” toxicities, such as cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and life-threatening cytokine storms [32–34]. Master mix of the active components of the TITE may serve as a potent anti-tumor and immune-activating drug that can provide more control in key processes and overcome the therapeutic limitations. In vivo experiments using active componenets of TITE packaged in targeted nano particles warrants further investigation.

The development of a broad tumor-specific adaptive immune response due to epitope-spreading as a consequence of tumor destruction and inflammation has long been proposed to be an important secondary mechanism underlying the potency of immunotherapy. This strategy will maximize anti-tumor efficacy and promote long-term immunity against cancer, leading to superior outcomes for patients fighting this disease and durable anti-tumor responses. Our innovative cell-free therapeutic platform focuses on long lasting anti-tumor immunity through induction of in situ immunization (Fig. 5b).

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Dr. Manley T. Huang for his help with antigen expression on tumor cells. These studies were funded in part by R01 CA 092344 (L.G.L.), R01 CA 140412 (L.G.L), 5P39 CA 022453 from the National Cancer Institute, and startup funds from the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute and the University of Virginia.

Author contributions

AT and LGL conceived and designed the study, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript. LGL and BFS participated in the design of the study and helped in drafting the manuscript. SVK, KJ, DLS, EB, JU, AA, EC performed the experiments and participated in the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was primarily supported by funding from in part by DHHS R01 CA 092344, R01 CA 140314, R01 CA 182526, P30CA022453 (Microscopy, Imaging, and Cytometry Resources Core) and startup funds from the University of Virginia Cancer Center.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

AT is co-founder of Nova Immune Platform Inc.; LGL is co-founders of TransTarget, Inc; SVK, KJ, DLS, EB, JU, AA, EC and BFS have no conflict of interest. The data presented in this manuscript are original and have not been published elsewhere except in the form of abstracts and poster presentations at symposia and meetings.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Archana Thakur and Sri Vidya Kondadasula have shared authorship.

References

- 1.Lum LG, et al. Targeted T-cell therapy in stage IV breast cancer: a phase I clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(10):2305–2314. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaishampayan U, et al. Phase I study of anti-CD3 × anti-Her2 bispecific antibody in metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer patients. Prostate Cancer. 2015;2015:285193. doi: 10.1155/2015/285193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thakur A, et al. Immune T cells can transfer and boost anti-breast cancer immunity. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7(12):e1500672. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1500672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thakur A, Lum LG. In Situ immunization by bispecific antibody targeted T cell therapy in breast cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(3):e1055061. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1055061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sen M, et al. Use of anti-CD3 × anti-HER2/neu bispecific antibody for redirecting cytotoxicity of activated T cells toward HER2/neu+ tumors. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2001;10(2):247–260. doi: 10.1089/15258160151134944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thakur A, Norkina O, Lum LG. In vitro synthesis of primary specific anti-breast cancer antibodies by normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60(12):1707–1720. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1056-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thakur A, et al. A Th1 cytokine-enriched microenvironment enhances tumor killing by activated T cells armed with bispecific antibodies and inhibits the development of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61(4):497–509. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1116-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez C, Huebener P, Schwabe RF. Damage-associated molecular patterns in cancer: a double-edged sword. Oncogene. 2016;35(46):5931–5941. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thakur A, et al. Microenvironment generated during EGFR targeted killing of pancreatic tumor cells by ATC inhibits myeloid-derived suppressor cells through COX2 and PGE2 dependent pathway. J Transl Med. 2013;11:35. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pardo J, et al. Apoptotic pathways are selectively activated by granzyme A and/or granzyme B in CTL-mediated target cell lysis. J Cell Biol. 2004;167(3):457–468. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goping IS, et al. Granzyme B-induced apoptosis requires both direct caspase activation and relief of caspase inhibition. Immunity. 2003;18(3):355–365. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Liu Z. STAT1 in cancer: friend or foe? Discov Med. 2017;24(130):19–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rauch I, Muller M, Decker T. The regulation of inflammation by interferons and their STATs. JAKSTAT. 2013;2(1):e23820. doi: 10.4161/jkst.23820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Able AA, Burrell JA, Stephens JM. STAT5-interacting proteins: a synopsis of proteins that regulate STAT5 activity. Biology (Basel) 2017;6(1):20. doi: 10.3390/biology6010020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimberg A, et al. Ser727/Tyr701-phosphorylated Stat1 is required for the regulation of c-Myc, cyclins, and p27Kip1 associated with ATRA-induced G0/G1 arrest of U-937 cells. Blood. 2003;102(1):254–261. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoefig KP, Heissmeyer V. Posttranscriptional regulation of T helper cell fate decisions. J Cell Biol. 2018;217(8):2615–2631. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201708075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu W, et al. T lymphocyte SHP2-deficiency triggers anti-tumor immunity to inhibit colitis-associated cancer in mice. Oncotarget. 2017;8(5):7586–7597. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su YL, et al. STAT3 in tumor-associated myeloid cells: multitasking to disrupt immunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1803. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao D, et al. VEGF drives cancer-initiating stem cells through VEGFR-2/Stat3 signaling to upregulate Myc and Sox2. Oncogene. 2014;34:3107. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogin L, Degani H. Hormonal regulation of VEGF in orthotopic MCF7 human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62(7):1948–1951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee TH, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor modulates the transendothelial migration of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells through regulation of brain microvascular endothelial cell permeability. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(7):5277–5284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Binnemars-Postma K, et al. Targeting the Stat6 pathway in tumor-associated macrophages reduces tumor growth and metastatic niche formation in breast cancer. FASEB J. 2018;32(2):969–978. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700629R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torri A, et al. Extracellular microRNA signature of human helper T cell subsets in health and autoimmunity. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(7):2903–2915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.769893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Podshivalova K, Salomon DR. MicroRNA regulation of T-lymphocyte immunity: modulation of molecular networks responsible for T-cell activation, differentiation, and development. Crit Rev Immunol. 2013;33(5):435–476. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.2013006858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez-Galan A, Fernandez-Messina L, Sanchez-Madrid F. Control of immunoregulatory molecules by miRNAs in T cell activation. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2148. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Testa U, et al. miR-146 and miR-155: two key modulators of immune response and tumor development. Noncoding RNA. 2017;3(3):22. doi: 10.3390/ncrna3030022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang Y, Pan HF, Ye DQ. microRNAs function in CD8+T cell biology. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;97(3):487–497. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1RU0814-369R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paladini L, et al. Targeting microRNAs as key modulators of tumor immune response. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:103. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0375-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cioffi M, et al. The miR-25-93-106b cluster regulates tumor metastasis and immune evasion via modulation of CXCL12 and PD-L1. Oncotarget. 2017;8(13):21609–21625. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu Z, et al. microRNA 17/20 inhibits cellular invasion and tumor metastasis in breast cancer by heterotypic signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(18):8231–8236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soleimani A, et al. Role of TGF-beta signaling regulatory microRNAs in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2019 doi: 10.1002/jcp.28169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porter DL, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(8):725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guedan S, Ruella M, June CH. Emerging cellular therapies for cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2018 doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042718-041407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watanabe K, et al. Expanding the therapeutic window for CAR T cell therapy in solid tumors: the knowns and unknowns of CAR T cell biology. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2486. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.