Abstract

Preeclampsia is a pregnancy-specific hypertensive disorder characterized by proteinuria, and vascular injury in the second half of pregnancy. We hypothesized that endothelium-dependent vascular dysfunction is present in a murine model of preeclampsia based on administration of human preeclamptic sera to interleukin −10−/− mice and studied mechanisms that underlie vascular injury. Pregnant wild type and IL-10−/− mice were injected with either normotensive or severe preeclamptic patient sera (sPE) during gestation. A preeclampsia-like phenotype was confirmed by blood pressure measurements; assessment of albuminuria; measurement of angiogenic factors; demonstration of foot process effacement and endotheliosis in kidney sections; and by accumulation of glycogen in placentas from IL-10−/− mice injected with sPE sera (IL-10−/−sPE). Vasomotor function of isolated aortas was assessed. The IL-10−/−sPE murine model demonstrated significantly augmented aortic contractions to phenylephrine and both impaired endothelium-dependent and, to a lesser extent, endothelium-independent relaxation compared to wild type normotensive mice. Treatment of isolated aortas with indomethacin, a cyclooxygenase inhibitor, improved, but failed to normalize contraction to phenylephrine to that of wild type normotensive mice, suggesting the additional contribution from nitric oxide downregulation and effects of indomethacin-resistant vasoconstricting factors. In contrast, indomethacin normalized relaxation of aortas derived from IL-10−/−sPE mice. Thus, our results identify the role of IL-10 deficiency in dysregulation of the cyclooxygenase pathway and vascular dysfunction in the IL-10−/−sPE murine model of preeclampsia, and point towards a possible contribution of nitric oxide dysregulation. These compounds and related mechanisms may serve both as diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets for preventive and treatment strategies in preeclampsia.

Keywords: preeclampsia, interleukin-10, vascular reactivity, mouse

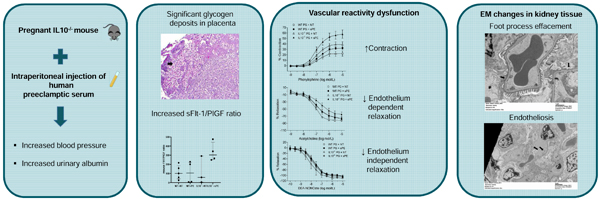

Graphical abstract

CONCLUSION:

IL-10 deficient murine model of preeclampsia is associated with vascular reactivity dysfunction, due to dysregulation in cyclooxygenase pathway, with a possible role of NO downregulation.

INTRODUCTION

Preeclampsia (PE) is a pregnancy disorder characterized by hypertension accompanied by proteinuria and/or organ dysfunction during the second half of pregnancy.1 It remains a major cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality worldwide.2 It has been increasingly recognized that PE is a heterogeneous disease.3 “Placental” PE has been associated with placental ischemia and impaired angiogenesis, as demonstrated by elevated levels of the soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-1 (sFlt-1), a soluble receptor of placental origin, which may bind and neutralize pro-angiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and placental growth factor (PlGF).4 This form of PE is commonly associated with an increase in the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio compared to normotensive pregnancies and is clinically characterized by early presentation (<34 gestational weeks), and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). “Maternal” PE occurs in the setting of preexisting maternal comorbidities such as chronic hypertension and diabetes mellitus, whereby pregnancy acts as a physiological stress test that exacerbates preexisting endothelial dysfunction. These classifications (placental vs. maternal, early vs. late, severe vs. mild) are likely overly simplistic as these forms tend to overlap. However, their converging point seems to be systemic endothelial dysfunction, resulting in vascular injury, inflammation, and platelet activation.5 The underlying molecular mechanisms are still poorly defined, despite recent advances in the understanding of the pathophysiological processes related to this disorder. Normal pregnancy requires a maternal state of immune tolerance to the semi-allogenic fetus. Consequently, Th1 responses are suppressed, while Th2 responses are enhanced (commonly referred to as “Th2 polarization”). 6 Th2 polarization results in shifting of the maternal immune system away from cell-mediated, Th1 immunity, which could be detrimental to the fetus. In contrast, PE is characterized by a Th1/Th2 predominant state.6–8 A key mediator of Th2-mediated immune balance during pregnancy is interleukin 10 (IL-10). Its role in normal pregnancy and dysregulation in PE is supported by several lines of evidence. First, IL-10 plays an important role in normal pregnancy as an anti-inflammatory cytokine,9,10 with vasoprotective properties,11–16 and its downregulation may contribute to the known pathophysiological features of PE, its pro-inflammatory milieu and vascular injury. Second, decreased levels of IL-10 are identified in PE and PE-like syndromes.5,17–19 Third, IL-10 protects against endothelial dysfunction, a hallmark of vascular injury in PE.20 Fourth, a seminal study that used pregnant IL-10−/− mice, showed that the mice injected with sera from PE patients 21 demonstrated classic signs of PE, including hypertension and albuminuria, along with glomerular endotheliosis, placental hypoxic injury, and increased anti-angiogenic factor levels, including fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor-1 (sFlt-1) and soluble endoglin (sEng).This model was further validated by experiments showing that hypoxia, which has long been implicated in the pathophysiology of PE, induced placental injury and increased placental expression and release of sFlt-1 and sEng, with a particularly severe phenotype in the absence of IL-1022. This model of PE, dependent upon IL-10 deficiency along with the plethora of vasoactive factors in PE sera, offered the unique opportunity to investigate clinically relevant features of this disease. However, vascular function and reactivity, which are significantly impaired in PE, have not yet been studied in this model.

We hypothesized that the IL-10 knock-out model of PE would exhibit endothelium-dependent macrovascular dysfunction and that these studies might provide mechanistic data regarding vascular dysfunction in preeclampsia, thus identifying potential therapeutic targets.

RESULTS

1. Characterization of the murine PE model

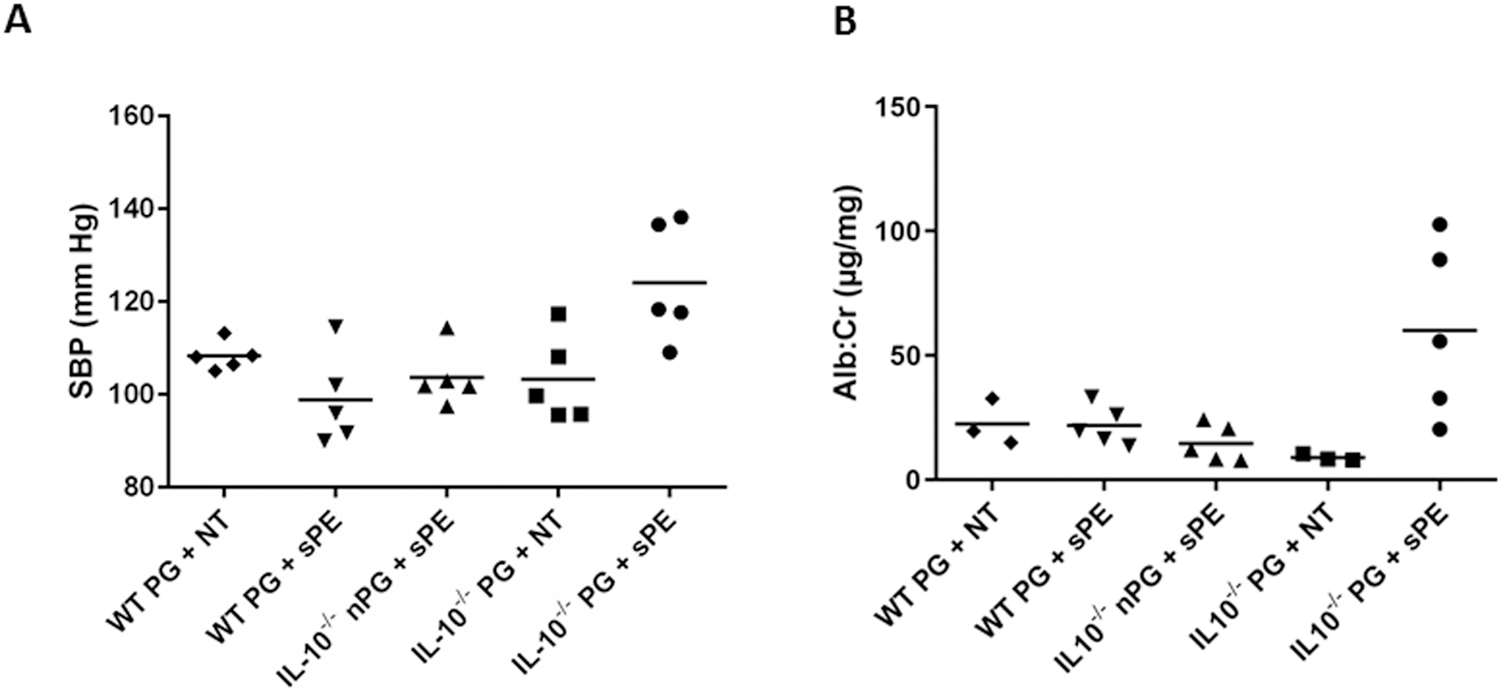

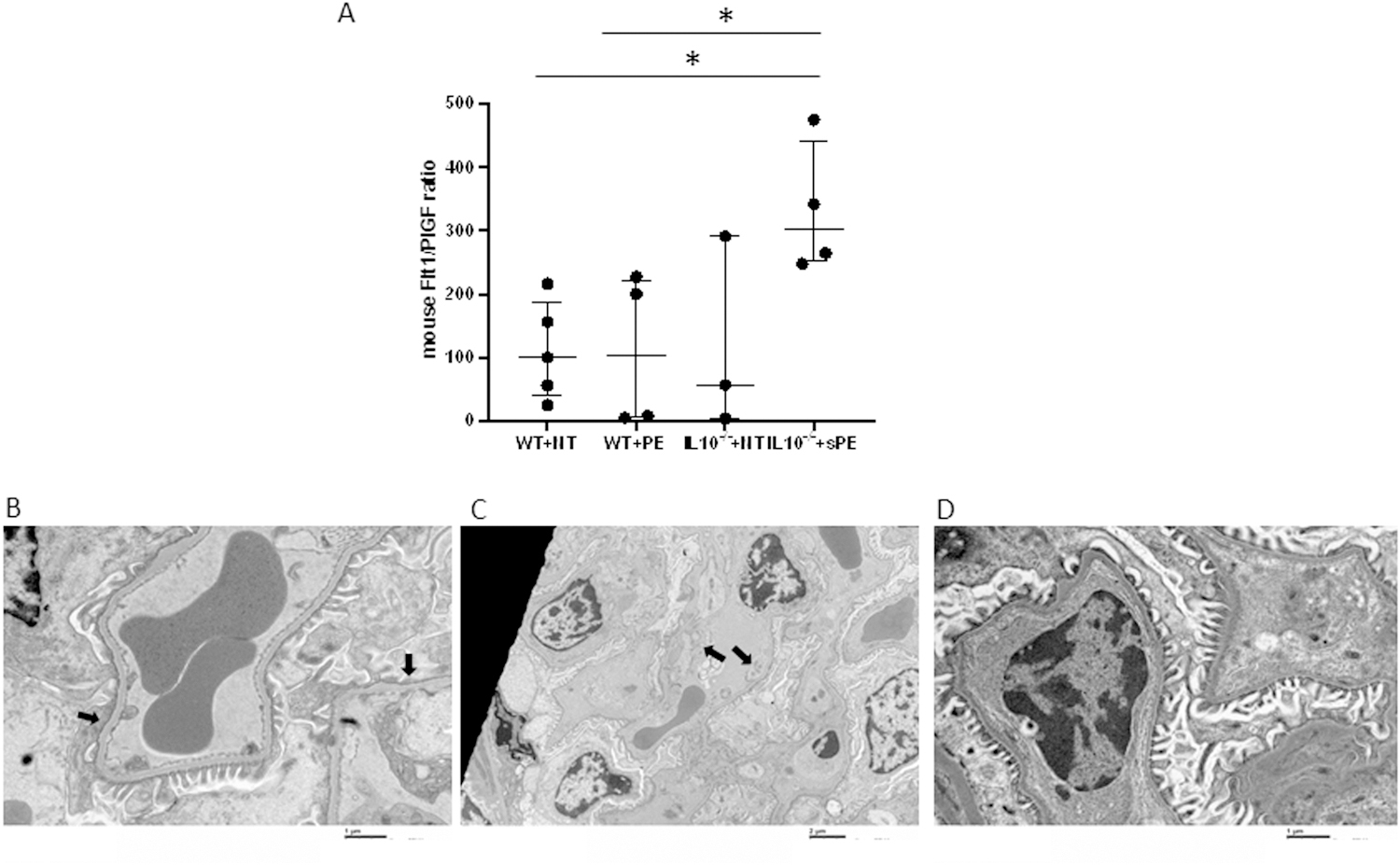

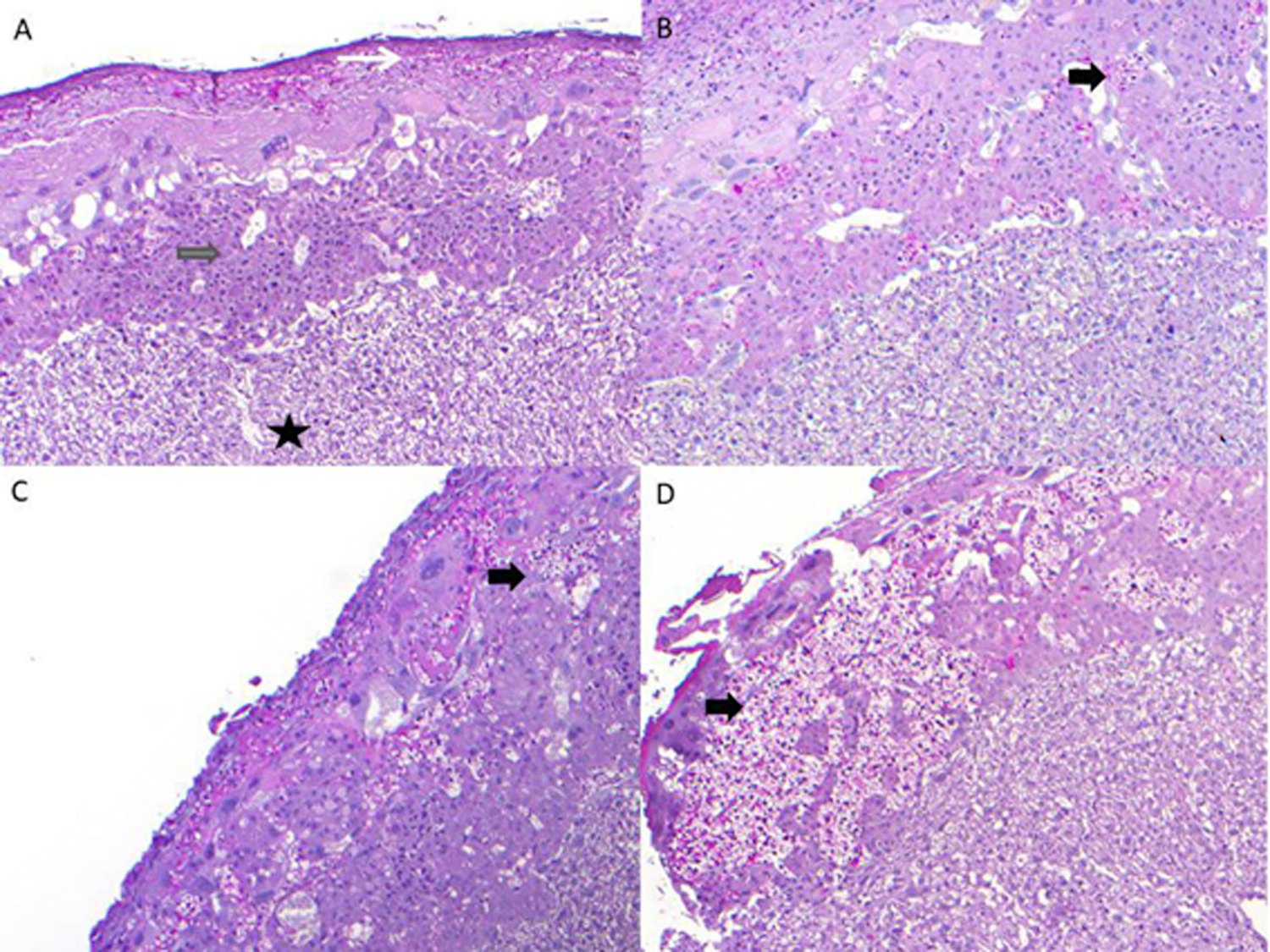

The following experimental groups were studied: pregnant wild-type (WT) or IL-10 knock-out (IL-10−/−) mice injected with either normotensive (NT) or pooled severe PE sera (sPE). All four groups were analyzed: one modeling the “normal pregnancy state” (pregnant WTNT), two intermediate phenotypes, WTsPE and IL-10−/−NT, and the “PE pregnancy state” (pregnant IL-10−/−sPE). This design allowed us to study the development of a PE-like state as a function of both the isolated and combined effects of the components of this animal model (i.e., IL-10absence/presence and type of serum). IL-10−/−sPE experienced elevated blood pressures and higher albumin/creatinine (Alb/Cr) ratios compared to pregnant IL-10−/− mice injected with normotensive (NT) sera (IL-10−/−NT), as well as pregnant WT mice injected with either sPE (WTsPE) or NT sera (WTNT) (p<0.05 for all) (Figure 1A and 1B). The effect of sPE serum injection was pregnancy-specific, producing higher blood pressures and Alb/Cr ratios in pregnant compared to non-pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice (p<0.05 for all) (Figure 1A and 1B). This was accompanied by elevation of the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio in mice sera (Figure 2a), with electron microscopy of the kidney sections in IL-10−/−sPE, showing foot process effacement (Figure 2b) and endotheliosis (Figure 2c), which were absent in the other 3 phenotypes (Figure 2d). Furthermore, placentas from IL-10−/−sPE showed an increase in glycogen content, similar to glycogen accumulation that has been demonstrated previously in preeclamptic placentas, both in human studies and in animal models 23 (Figure 3). Descriptive litter data are given in Figure S1. Of note, the pups from the IL-10−/−sPE pregnant mice did not show a decrease in the total litter weight, which would argue against placental ischemia, despite abnormal placental findings (e.g., an increase in the placental glycogen content).

Figure 1:

Blood pressure and albuminuria at harvest in WT and IL-10−/− mice injected with human NT or sPE sera. Systolic blood pressure (A) and urinary Alb/Cr ratios (B) at harvest, n=5 per group. Dots represent individual level data, and lines represent means. One-Way ANOVA with least significant differences as a post hoc test was used for the analysis. (A) Pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice had significantly elevated SBP compared to pregnant WTNT (p=0.012), WTsPE (p<0.001), and IL-10−/−NT (p=0.002), as well as to non-pregnant IL-10−/−sPE (p=0.002) mice. (B) Pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice had significantly increased urine albumin to creatinine ratios compared to pregnant WTNT (p=0.018), WTsPE (p=0.007) and IL-10−/−NT mice (p=0.003), as well as to non-pregnant IL-10−/−sPE (p=0.004) mice.

SBP, systolic blood pressure; Alb/Cr, albumin to creatinine ratio; WT, wild type mice; IL-10−/−, interleukin-10 deficient mice; PG, pregnant; nPG, non-pregnant, NT, normotensive, sPE, severe preeclamptic

Figure 2: Angiogenic markers and renal histology in WT and IL10−/− mice injected with either NT or sPE sera.

There was a statistical difference between WTNT and IL-10−/−sPE mice (p=0.016), as well as between WTsPE and IL-10−/−sPE mice (p=0.029). Dots represent individual level data, and lines represent median and IQR. Data were analyzed using a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test (A) Significant foot process effacement (B, black arrows) and endotheliosis (C, black arrows) were observed in IL-10−/−sPE mice compared to control group (D). Images were taken by electron microscopy and magnifications were 15,000x, 6,000x and 15,000x, respectively.

WT, wild type mice; IL-10−/−, interleukin-10 deficient mice; NT, normotensive, sPE, severe preeclamptic

Figure 3: Glycogen content in placental tissue.

Placenta from WT+NT (A) demonstrates decidua (white arrow), junctional zone (grey arrow) without foci of glycogenation, the labyrinth is also represented (black star); Placenta from WT+PE shows small islands of glycogenation black thick arrow) in the junctional zone (B). The placenta from IL10−/− NT also shows small islands of glycogenation (black thick arrow) (C). The placenta from IL-10−/−sPE shows large confluent areas of glycogenation, replacing much of the junctional zone (D) The WTNT had 7.8% [0.16–12.3], whereas IL10−/−sPE were with 26.72% [16.86–34.48] of glycogenation area in relation to the total area of the junctional zone. There was a significant difference between aforementioned mice (p=0.0095), as well as between WTsPE (7.9% [3.9–13.1]) and IL10−/−sPE groups (p=0.043). No statistical difference was observed between IL10−/−sPE and IL10−/−NT mice (15.2% [1.2–30.9]). Values presented as median with IQR.

WT, wild type mice; IL-10−/−, interleukin-10 deficient mice; NT, normotensive, sPE, severe preeclamptic

2. Vascular reactivity in WT and IL-10−/− aortas after injection with patient sera

We studied phenylephrine-induced contraction; endothelium-dependent relaxation (EDR) to acetylcholine, which is mediated by endothelium-derived NO; and endothelium-independent relaxation (EIR) to diethylammonium (Z)-1-(N,N-diethylamino)diazen-1-IM1,2-diolate (DEA-NONOate), a nitric oxide (NO) donor, which exerts a direct effect on smooth muscle cells. Its relaxation effect, unlike relaxation to acetylcholine, is independent of the presence of intact endothelium. To determine the possible contribution of arachidonic acid metabolites produced by activation of cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway to vascular reactivity, we also studied EDR and EIR in the presence of the COX inhibitor, indomethacin.

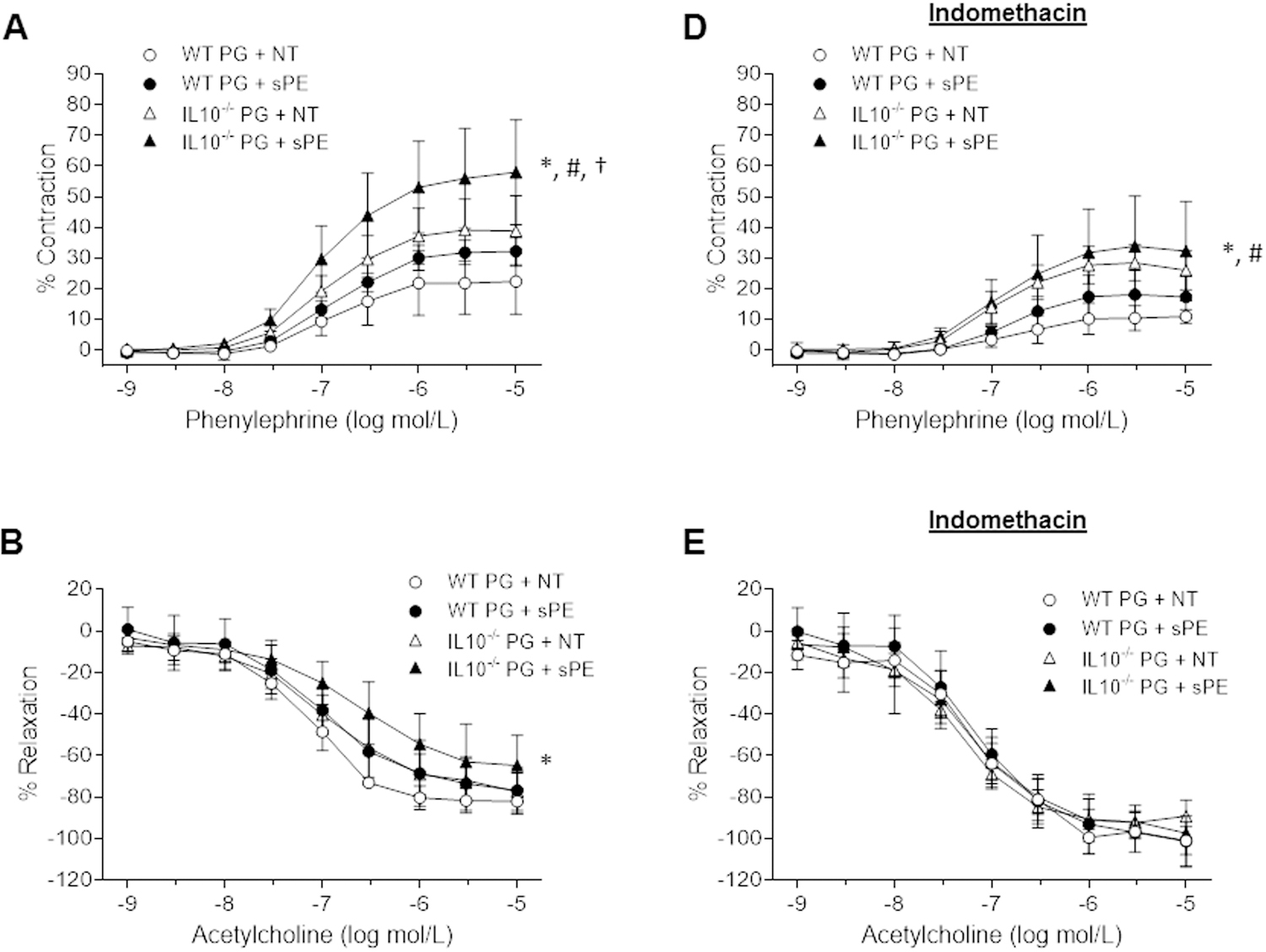

Responses to known vasoactive molecules in pregnant IL-10−/− and WT mice injected with either NT or sPE patient sera are illustrated in Figure 4. Phenylephrine (10−9–10−5 M) induced concentration-dependent contractions in all groups (Figure 4A). Pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice exhibited enhanced aortic contractions to phenylephrine compared to pregnant WTNT (p<0.001), WTsPE (p=0.002), as well as IL-10−/−NT mice (p=0.022). Emax (measure of efficacy, see Methods), and pEC50 (measure of potency, see Methods) for phenylephrine were lowest for WTNT and highest for IL-10−/−sPE mice (22±5 vs. 57±7 for Emax, and 6.9±0.03 vs. 7.0±0.02 for pEC50, respectively, Table 1).

Figure 4:

Aortic reactivity in pregnant WT and IL-10−/− mice injected with NT and sPE human sera. Concentration-dependent contractions in response to phenylephrine in the absence (A) and presence of indomethacin (D), relaxation in response to acetylcholine in the absence (B) and presence of indomethacin (E), and relaxation in response to DEA-NONOate in the absence (C) and presence of indomethacin (F). Results are expressed as mean ± SD of percent contraction to 80 mM KCl/relaxation to submaximal contraction induced by phenylephrine, n=5 per group. Data were analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA (between-subjects factor: group; within subjects factor: vasoactive substance concentration). Phenylephrine and acetylcholine had 9 concentration categories (10−9–10−5). DEA-NONOate had 11 concentration categories (10−10–10−5); Indomethacin (10−5 mol/L; 30 min).

(A) Pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice had significantly higher contractions to phenylephrine compared to the pregnant WTNT (p<0.001), WTsPE (p=0.002) and IL-10−/−NT (p=0.022) mice. (D) Indomethacin significantly decreased contraction to phenylephrine (p<0.05 for all groups before and after exposure to indomethacin). Even in the presence of indomethacin, the pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice exhibited enhanced contraction to phenylephrine compared to the pregnant WT mice (p=0.001 and p=0.013, in comparison to the WTNT and WTsPE mice, respectively). (B) Pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice had significantly decreased endothelium-dependent relaxation to acetylcholine compared to pregnant WTNT (p=0.004). When compared to pregnant WTsPE and IL-10−/−NT mice, there was a trend towards a difference, although not statistically significant (p=0.140 and p=0.057, respectively). (E) Indomethacin significantly increased relaxation to acetylcholine in all groups (p<0.05 for each groups before and after exposure to indomethacin). There was no significant difference between the groups after exposure to indomethacin (p>0.05 between the groups). (C) Pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice had significantly impaired endothelium-independent relaxation to DEA-NONOate compared to the WTNT (p=0.007) mice, but this effect was less pronounced than for relaxation to acetylcholine. (F) There was no significant difference between the groups after exposure to indomethacin. Of note, the relaxation before and after indomethacin for WTNT remained the same (p=0.35) , while all three other groups demonstrated increase in EIR (p<0.05 for each groups before and after exposure to indomethacin).

WT, wild type mice; IL-10−/−, interleukin-10 deficient mice; PG, pregnant; NT, normotensive, sPE, severe preeclamptic.

* IL10−/−sPE vs. WTNT, # IL10−/−sPE vs. WTsPE, † IL10−/−sPE vs. IL-10−/−NT

Table 1:

Efficacy and potency of vasoactive agents in isolated aortic rings

| Group | Phenylephrine | Acetylcholine | DEA-NONOate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pEC50 (−log mol/L) | Emax (%) | pEC50 (−log mol/L) | Emax (%) | pEC50 (−log mol/L) | Emax (%) | |

| WTPG + NT | 6.88±0.03 | 22±5 | 7.10±0.05 | 82±3 | 8.00±0.18 | 109±1 |

| WT PG + sPE | 6.85±0.04 | 33±2 | 6.90±0.14 | 79±4 | 7.77±0.05 | 101±1 |

| IL-10−/− PG + NT | 6.97±0.03 | 39±5 | 6.94 ±0.08 | 77±4 | 7.65±0.07 | 103±2 |

| IL-10−/− PG + sPE | 7.00±0.02 | 57±7 | 6.68±0.11 | 65±7 | 7.84±0.07 | 100±1 |

| IL-10−/− nPG + sPE | 7.02±0.08 | 57±13 | 7.17±0.07 | 88±2 | 7.89±0.03 | 103±1 |

Emax indicates efficacy; pEC50, potency; WT, wild-type; IL10−/−, interleukin10-knockout; PG, pregnant; NT, normotensive; sPE, severe preeclamptic. Data are means ± SEM (n=5 per group).

Endothelium-dependent relaxation (of aortic segments in response to acetylcholine (10−9 – 10−5 M) is presented in Figure 4B. The relaxation to acetylcholine was concentration dependent in all groups. Pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice displayed decreased EDR compared to the pregnant WTNT (p=0.004) mice, and similar trends in the pregnant WTsPE and IL-10−/−NT mice (p=0.140 and p=0.057, respectively). EDR in the pregnant IL-10−/−NT mice was similar to that of the WTsPE (p=0.629) mice, suggesting similar EDR responses in the intermediate phenotypes. Emax and pEC50 for acetylcholine were highest in the WTNT and lowest for the IL-10−/−sPE mice (82±3 vs. 65±7 for Emax, and 7.1±0.05 vs. 6.7±0.11 for pEC50, respectively, Table 1).

Figure 4C illustrates the EIR of aortic segments for the groups in response to DEA-NONOate (10−10–10−5 M), which acts directly on vascular smooth muscle and induces relaxation. Pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice displayed decreased EIR compared to the pregnant WTNT mice (p=0.007), while there was no difference in contrast to intermediate phenotypes, WTsPE and IL-10−/−NT mice (p>0.05). However, the mean difference *(MD) of EIR in the pregnant IL-10−/−sPE compared to pregnant WTNT mice was less pronounced (MD: 8%) compared to the differences seen in EDR (MD: 15%) for the same groups. These findings suggest that in this PE model, reactivity of aortic smooth muscle cells to NO is slightly impaired.

Additional mechanistic insights into the observed vascular dysfunction were gained through ex vivo exposure of murine aortas to indomethacin, a potent COX inhibitor (Figure 4D, 4E, 4F). Treatment with indomethacin (10−5 mol/L; 30 min) significantly decreased phenylephrine-induced contractions (4D) in both the pregnant IL-10−/− and pregnant WT mice (p<0.05 for all groups before and after exposure to indomethacin). Even in the presence of indomethacin, the pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice exhibited enhanced contractions to phenylephrine compared to the pregnant WT mice (p=0.001 and p=0.013, compared to WTNT and WTsPE, respectively. Indomethacin significantly increased acetylcholine-induced relaxation of aortic rings (4E) in both pregnant IL-10−/− and pregnant WT mice (p<0.05 for each group before and after exposure to indomethacin). However, the previously noted differences in relaxation between the groups (4B) were no longer seen after indomethacin treatment (p>0.05 between the groups) (Figure 4E), suggesting that the observed alteration in EDR is predominantly caused by enhanced activation of the COX pathway. Similar to EDR, the previously noted differences in EIR relaxation between the groups (4C) were no longer evident after exposure to indomethacin (4F).

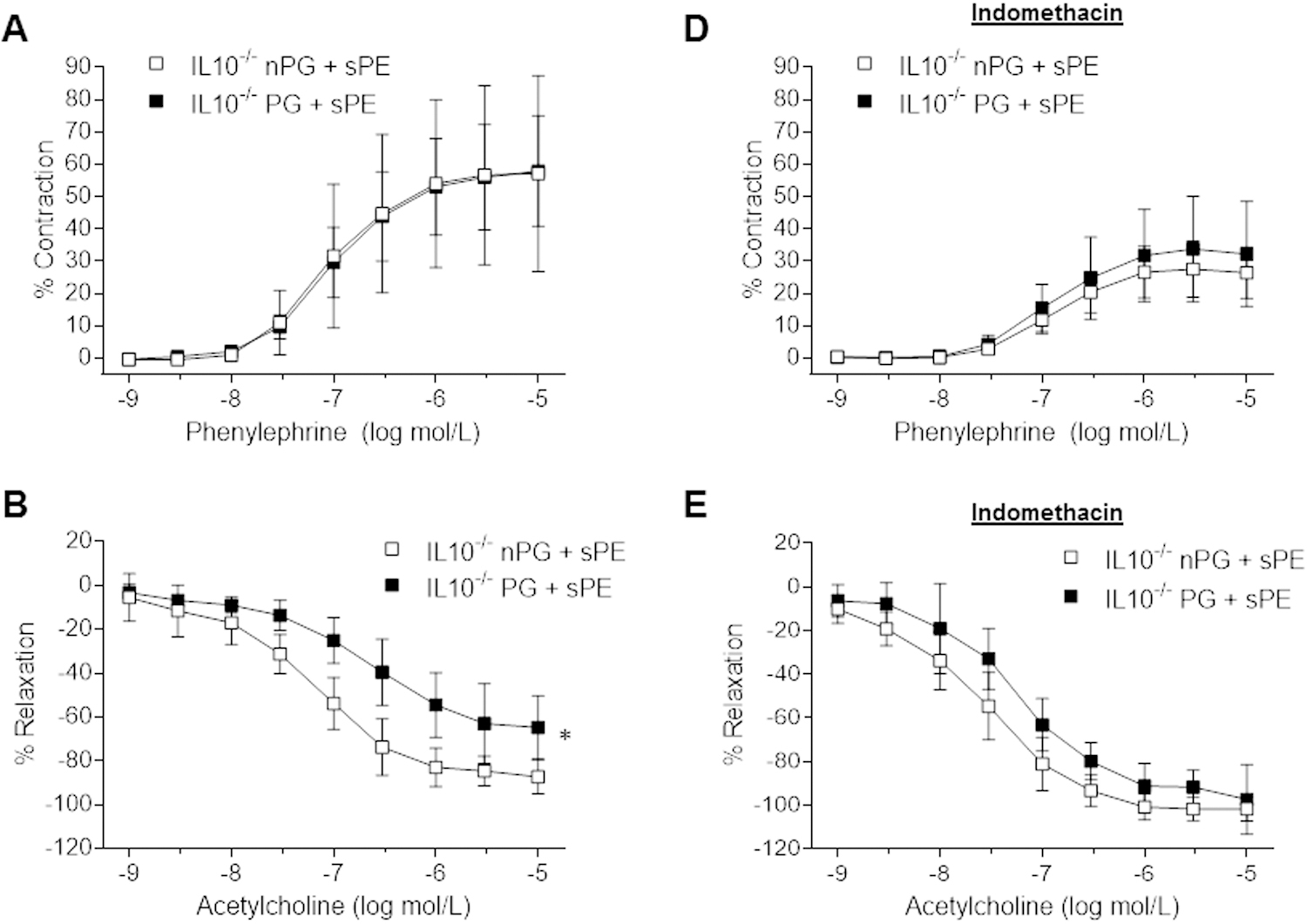

In order to assess whether the vascular dysfunction was pregnancy-specific, we analyzed vascular function in pregnant vs. non-pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice. As shown in Figure 5, contractions to phenylephrine and EIR responses did not vary between the pregnant and non-pregnant groups (phenylephrine: p=0.971, Figure 5A; DEA-NONOate: p=0.138; Figure 5C), in contrast to the impaired EDR found in the pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice (p=0.007; Figure 5B). Incubation with indomethacin reduced contractions to phenylephrine, while simultaneously improving EDR in the IL-10−/−sPE mice, irrespective of pregnancy status (p<0.05 for all comparisons, Figure 5D and 5E). There were no significant differences in relaxation to DEA-NONOate in aortas treated with indomethacin (p=0.124).

Figure 5:

The effect of pregnancy in IL-10−/− mice injected with sPE sera on aortic reactivity. Concentration-dependent contraction to phenylephrine in the absence (A) and presence of indomethacin (D), relaxation to acetylcholine in the absence (B) and presence of indomethacin (E), and relaxation to DEA-NONOate in the absence (C) and presence of indomethacin (F). Results are expressed as mean ± SD of percent contraction to 80 mM KCl/percent relaxation to submaximal contraction induced by phenylephrine, n=5 per group. Data were analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA (between-subjects factor: group; within subjects factor: vasoactive substance concentration). Phenylephrine and acetylcholine had 9 concentration categories (1E-9 – 1E-5) and DEA-NONOate had 11 concentration categories (1E-10 – 1E-5); Indomethacin (10−5 mol/L; 30 min).

(A) There were no significant differences in contraction to phenylephrine between the pregnant and non-pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice (p=0.971). (D) Indomethacin significantly decreased contractions to phenylephrine in both the pregnant and non-pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice (p<0.05 for both). (B) Pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice had significantly impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation compared to the non-pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice (p=0.007). (E) Indomethacin improved endothelium-dependent relaxation in both the pregnant and non-pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice (p<0.05 for both), and there were no differences between the groups after exposure to indomethacin (E). There were no significant differences in relaxation to DEA-NONOate between the pregnant and non-pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice (p=0.138) before (C) and after indomethacin (p=0.124) (F).

WT, wild type; IL-10−/−, interleukin-10 knockout; PG, pregnant; nPG, non-pregnant; NT, normotensive; sPE, severe preeclamptic, * Pregnant IL10−/−sPE vs. non-pregnant IL-10−/−sPE

To further elucidate the molecular mechanisms responsible for the observed vascular dysfunction, we analyzed the aortic gene expressions of COX (Table S2). There were no differences in the expressions of COX isoforms, COX1 and COX2, between the IL-10−/−sPE and WTNT groups (p=0.281 and p=0.281, respectively; Table S2).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, our present study reports several novel findings obtained in an IL-10−/− mouse model of PE that provide mechanistic data for the role of IL-10 deficiency in human disease. First, we demonstrate that pregnant IL-10−/−sPE exhibits several features of human disease, including angiogenic imbalance (i.e. elevated sFlt-1/PlGF ratio); foot process effacement and endotheliosis, which are considered to be classical renal histological findings in PE; and placental glycogen accumulation which is increasingly recognized and considered to be the result of either impaired utilization or compensation for placental dysfunction in PE. Second, we detected altered vasomotor function of isolated aortas, including enhanced contractions to phenylephrine, as well as impaired EDR to acetylcholine and, to a lesser extent, EIR to DEA-NONOate. Third, the impairment of vascular function was pregnancy-specific and predominantly derived from impaired EDR. Fourth, indomethacin improved vasoconstriction and corrected vasodilator dysfunction, thus suggesting enhanced activation of the COX pathway, with an imbalance between vasodilatory and vasoconstricting prostaglandins, in favor of the latter.24 Taken together, these results characterize vascular dysfunction and identify the COX pathway as the underlying mechanism in the setting of decreased IL-10 levels. Based on the data showing that indomethacin improved, but failed to normalized contraction to phenylephrine in the murine model of PE, our study further points towards a possible contribution of indomethacin-resistant vasoconstricting factors and/or NO dysregulation in vascular damage in PE.

Both a preeclampsia-like phenotype and vascular dysfunction in the present model require a combination of a) pregnant state; b) IL-10 deficiency; and c) exposure to sPE sera. The use of either of these alone failed to recapitulate the extent of vascular dysfunction observed. This combination establishes the clinical fidelity of this model because IL-10 levels are reduced in clinical PE5. The relevance of these findings with respect to the clinical PE phenotype is further underscored by the effects of pregnancy on the severity of the phenotype: hypertension and albuminuria were the most severe in pregnant IL-10−/− mice injected with sPE sera; non-pregnant IL-10−/− mice injected with sPE sera behaved similarly to pregnant IL-10−/− mice injected with NT sera. We recognize, however, that our results obtained in isolated aortas (large conduit vessels) may not reflect changes in small resistance arteries.

The IL-10 knock-out model is commonly used for studies of aging, and senescence, an irreversible cell-cycle arrest mechanism that leads to senescence-related injury that is, in part, mediated by the release of pro-inflammatory markers.25 Previous reactivity studies in non-pregnant IL-10−/− mice suggest that IL-10 deficiency predisposes to EDR impairment in response to vascular stressors such as angiotensin II (ANGII),26,27 endothelin-1 (ET-1),13 tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-ɑ),11,28 lipopolysaccharide (LPS),14,16 chronic hyperglycemia,15 and aging.20,29 Taken together, these data imply that a “second hit” is needed to induce vascular dysfunction in the setting of IL-10 deficiency. Indeed, PE sera contain many vasoactive mediators, including TNF-ɑ, ANGII, stimulating ANGII receptor-1 auto-antibodies (AT1-AA), and ET-1.30–33

Vascular reactivity studies demonstrated heightened contractions to phenylephrine and both impaired EDR and, to a lesser extent, EIR in the pregnant IL10−/−sPE mice. With EDR demonstrating a greater effect, the observed impaired relaxation in this model primarily reflects endothelial dysfunction. The clinical corollaries to our observations are human studies supporting both exaggerated responses to vasoconstrictors and endothelial dysfunction in women with PE. For example, studies of omental arteries from women diagnosed with PE demonstrate increased sensitivity to vasoconstrictors, ANGII and phenylephrine, compared to those measured from the omental arteries of NT women.34 Furthermore, these ex vivo observations are consistent with in vivo reports of differential responses to ANGII between NT and PE women.35–37 Finally, endothelial dysfunction, as measured by flow-mediated dilation, was lower in women with PE compared to those without PE, both before the development of PE (≈20–29 weeks gestation), and at the time of PE38 .

To explore the underlying mechanisms for the observed vascular dysfunction, mouse aortas were incubated in the presence of the nonselective COX inhibitor, indomethacin, as previously performed in hypertensive rats.39The rationale is based on a prior study showing that, under pathological conditions, such as hypertension, COX-derived vasoconstrictor products could be responsible for impairment of EDR to acetylcholine.39,40 Indomethacin prevented both the increased contractions to phenylephrine, as well as the impairment of both EDR and EIR in IL-10−/−sPE mice (Figure 4). However, in contrast to EDR and EIR, where the differences between the groups were no longer present after treatment with indomethacin, the IL-10−/−sPE mice continued to demonstrate significant residual, indomethacin-resistant contraction. As for the mechanism(s) for failure to normalize phenylephrine-induced contraction, we propose the possible roles of at least two mechanisms. First, we suggest that decreased NO bioavailability/production may be playing a role in the residual contraction based on the previous studies indicating that inactivation of basal production of NO by eNOS enhances the vasoconstrictor effect of phenylephrine41. In addition, decreased NO bioavailability/production may be driven by the increased production of superoxide anion by cyclooxygenase,42 which inactivates NO. Second, PE has been associated with several vasoconstricting mediators (e.g., endothelin-1 and angiotensin II), which are COX-independent, and thus may be contributing to the indomethacin-resistant component of phenylephrine-induced contraction. Angiogenic disbalance may potentiate the vasoconstricting effects of these mediators as shown by the action of sFlt-1(elevated levels in IL-10−/−sPE mice), which leads to enhanced angiotensin II sensitivity,43 one of the hallmarks of human disease. The link between these two mechanisms that may contribute to indomethacin-resistant contraction has been supported by studies demonstrating that angiotensin II sensitivity can be reversed by sildenafil, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, which enhances NO signaling,43 thus further supporting the role of decreased NO bioavailability/production in vascular injury in PE.

Current observations, interpreted in the context of the previous studies, suggest that both the COX and the NO pathways are involved, but that the primary abnormality is in the COX pathway, principally because indomethacin blocked the effect of PE sera and restored EDR in the pregnant IL-10−/−sPE mice. Comparable mRNA expression levels of COX1 and COX2 were detected, however, in the IL-10−/− mice injected with sPE sera and the WT mice injected with NT sera. Several considerations are relevant to these clear-cut functional effects of COX pathway inhibition on the one hand, and yet comparable expressions of COX1 and COX2 on the other: i) Vascular dysfunction may derive from factors upstream or downstream in the prostaglandin synthesis pathway; ii) significant differences in COX1/2 protein and mRNA expression levels may exist; and iii) enzymatic activity of COX1/2 may be altered. An additional consideration is that COX activity may generate superoxide anion which, in turn, inactivates NO thereby causing impairment of EDR.44 Indeed, PE plasma provokes EDR impairment in normal pregnant rat uterine arteries, and this adverse effect is abolished by a COX inhibitor, meclofenamide.45 Our present findings, in conjunction with such studies, support the beneficial effects of aspirin usage in pregnant women who are at high risk for PE.46

Several limitations are inherent in this particular PE model. One consideration is the variability of the PE patients whose sera were used. In order to better control for confounding variables, we employed pooled sera from several donor samples. Future studies would greatly benefit from using sera obtained from patients diagnosed with both mild and severe PE phenotypes, in order to characterize vascular injury across the spectrum of PE severity.

While reactivity studies with large conduit vessels were novel, the use of smaller resistance vessels may constitute a better indicator of peripheral resistance in this model. In addition, we did not measure relevant prostaglandin classes, but, based on the response to indomethacin, we concluded that there is a relative excess of vasoconstrictors, such as thromboxane, in our model. This would be consistent with human studies that have shown an imbalance in vasoactive prostaglandins, further characterized by reduced prostacyclin (vasodilatory agent) and unchanged levels of thromboxane, a vasoconstrictor, in preeclamptic compared to normotensive pregnancies.24 Regardless, important insights into the endothelial dysfunction typified in PE were observed with the use of aortas, the latter representing an established approach generally corroborated by the use of animal45 and human34 resistance vessels.

In summary, our results emphasize the role IL-10 deficiency in exaggerated vasoconstrictive responses and impaired vascular relaxation as mediated through both EDR and EIR, although the relative contribution of the EDR component appears greater. Based on responses to indomethacin, we conclude that the COX pathway is the primary abnormality, thus providing mechanistic data to support aspirin use for PE prevention. In addition, down-regulation of NO may contribute to impaired vascular responses, thus supporting the use of sildenafil in PE. Of note, the use of sildenafil and resultant increase in cyclic GMP (a second messenger for NO) has proven beneficial in reversing vasoconstriction in an ex vivo human placental model.47 In a subsequent step, we will decipher the role and relative contribution of NO dysregulation in vascular injury in the IL-10 deficient mouse model of PE. Of note, previous studies have indicated that IL-10 induces the production of NO 48 and that IL-10 infusion blunts the rise in blood pressure in response to angiotensin II.49 Future studies should explore the use of rIL-10 and/or other means of IL-10 administration as therapeutic options for PE, as well as COX and NO compounds and related mechanisms, which may serve both as diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets for prevention and treatment of preeclampsia.

METHODS

Patient sera

A convenience sample was obtained from each of five normotensive (NT) and five women diagnosed with severe PE (sPE) who were admitted to the Family Birth Center of the Mayo Clinic Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Preeclampsia was diagnosed as an elevated blood pressure (≥ 140/90 mm Hg) and either proteinuria (≥ 300 mg protein in a 24-h urine or urinary protein/creatinine ratio > 0.3), and/or organ dysfunction during the second half of pregnancy, according to accepted criteria.1 The diagnosis of severe PE was based on a systolic BP≥160 or diastolic BP≥110 mm Hg and/or signs and symptoms of end-organ damage,1 and further confirmed by an elevated sFlt-1/PlGF compared to normotensive controls (Table S1 and Figure S2). Experimental Details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Animals and Interventions

All animal studies were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (no. A-0000 2139–16), and in accordance with NIH guidelines). WT and IL-10−/−C57BL/6 mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (IL-10−/− mice stock no. 002251; WT mice stock no. 000664, Bar Harbor, ME). Experimental Details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Albuminuria assessment and blood pressure measurement

Urine albumin concentration , as a marker of glomerular injury, was determined using a mouse-specific ELISA kit (cat no. 41-ALBMS-E01, ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH) as directed by the manufacturer. Results were standardized by measuring urine creatinine with a creatinine colorimetric kit (cat no. 500701, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Urine Alb/Cr ratios were reported as μg of albumin/mg of creatinine. Blood pressures were measured using a noninvasive computerized tail-cuff system (CODA, Kent Scientific Corporation, Torrington, CT).50

Flt-1 and PlGF in serum

Both Fms-related tyrosine kinase 1 (Flt1) and placental growth factor (PlGF) were determined in human and mouse serum samples according to manufacturer protocol. The following ELISA kits were used (i) Human PlGF ELISA kit (ab100629, Abcam) (ii) Human VEGF R1 ELISA Kit (FLT1) (ab195210, Abcam) (iii) Mouse SimpleStep PlGF ELISA kit (ab197748, Abcam) (iv) Mouse Flt1 ELISA Kit (ab231935, Abcam).

Electron microscopy

Tissue was fixed in Trump’s fixative (1% glutaraldehyde and 4% formaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.2.51 Experimental Details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Glycogen deposits in placenta

Sections of placenta were stained with PAS/HE. Experimental Details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Vascular reactivity studies

The aortas were dissected and cleaned of fat and surrounding connective tissue in cold Krebs solution containing (in mmol/L): 118.6 NaCl; 4.7 KCl; 2.5 CaCl2; 1.2 MgSO4; 1.2 KH2PO4; 25.1 NaHCO3; 10.1 glucose; and 0.026 EDTA. Five mm-long rings were suspended in organ chambers for isometric force measurements (PowerLab, AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO) and the data were acquired with Labchart Pro software (AD Instruments) as previously described.52 Experimental Details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

qPCR studies

mRNA expression in aortas was assessed in the pregnant IL-10−/− and WT mice as described in our prior studies.53,54 Experimental Details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Statistical Analysis

Patient data are presented as means with standard deviations for continuous normally distributed variables and analyzed using an unpaired t test under the assumption of equal variance. Continuous non-normally distributed patient data are presented as medians with 25–75th percentiles and analyzed using the Mann Whitney U test. Data from animal studies are presented as individual level data, with corresponding summary measures, i.e. means, as well as standard deviations or standard errors. Blood pressure and albuminuria data were analyzed using One-way ANOVA (Post hoc: least significant difference). The effects of serum type, IL-10 availability, and prostaglandin pathway dysfunction on aortic vascular reactivity were examined by repeated measures ANOVA, with experimental animal group as a between subjects factor and vasoactive substance concentration as a within subjects factor, in the absence or presence of indomethacin. Aortic gene expression data were evaluated using an unpaired t test under assumption of equal variance. Analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (v25.0; IBM SPSS). Data are presented according to recently proposed guidelines for basic science data visualization 55A power calculation was not performed in advance, as this study is regarded as exploratory due to the lack of published data in this particular model.

Supplementary Material

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary methods: Patient sera, Animals and Interventions, qPCR, Electron microscopy, Glycogen deposits in placenta, Vascular reactivity studies

Table S1: Characteristics of patients providing serum samples

Table S2: Aortic COX gene expression analyses in WT and IL-10−/− mice

Figure S1: Fetal characteristics in WT and IL-10−/− mice injected with human NT and sPE sera. Total litter weights (A) and fetal lengths (B) in pregnant female WT and IL-10−/− mice. n = 5 per group. WT indicates wild type; IL-10−/−, interleukin-10 knockout; PG, pregnant; nPG, non-pregnant; NT, normotensive; sPE, severe preeclamptic. Data were analyzed by One-Way ANOVA with least significant differences as post hoc test: Total litter size: F=4.937, df=3, p=0.014 (IL-10−/− PG + NT had lowest total litter weight in comparison to other groups); Fetal length: F=1.500, df=3, p=0.258).

Figure S2: Individual sFlt-1/PlGF ratio values for human serum samples used to inject the animals. There was a significant difference between women with preeclampsia and normotensive women (Table S1).

TRANSLATIONAL STATEMENT.

Interleukin 10 (IL-10), a key mediator of Th2-immune responses, plays a major role in in normal pregnancy as an anti-inflammatory cytokine with vasoprotective properties. Clinical studies have provided data that IL-10 levels are decreased in preeclampsia (PE) compared to normotensive pregnancies. To study the role of IL-10 in the vascular injury associated with PE, we used pregnant interleukin-10−/− mice injected with severe preeclamptic sera, an animal model that proved to successfully recapitulate key clinical features of PE. Our results characterize vascular dysfunction in PE as enhanced vasoconstriction, impaired endothelium-dependent and, to a lesser extent, endothelium-independent relaxation, with a possible contribution from nitric oxide (NO) pathway dysregulation. Treatment of isolated aortas with indomethacin, a cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor, which improved contraction and normalized relaxation, provides mechanistic data that justify aspirin use for PE prevention. Additional studies exploring the role of NO down-regulation in vascular dysfunction in PE may provide preclinical data that will support the use of sildenafil, (a phosphodiesterase 5-inhibitor, which leads to increased eNO-mediated vasodilation) in PE. Finally, future studies exploring the incorporation of rIL-10 and/or other means of IL-10 administration as therapeutic options for PE will be of particular clinical interest and, based upon our study that utilized severe preeclamptic sera only, should discriminate between different forms of PE based on their severity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Anthony J. Croatt and Mr. Allan W. Ackerman for their technical expertise.

Source(s) of Funding

This study was supported by R01HL 136348 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Garovic), R01 DK 47060and R01 DK 119167 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Nath), AI 100911 (Grande), R01AG 013925 from the National Institute on Aging (Kirkland), the Connor Group (Kirkland), and the Noaber Foundation (Kirkland).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict(s) of Interest/Disclosure(s)

Authors declare no conflicts of interest

References:

- 1.American College of Obstetricians, Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. In: Obstetrics and Gynecology. Vol 122. Obstet Gynecol; 2013:1122–1131. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.George EM, Granger JP. Recent insights into the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5(5):557–566. doi: 10.1586/eog.10.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craici IM, Wagner SJ, Weissgerber TL, Grande JP, Garovic VD. Advances in the pathophysiology of pre-eclampsia and related podocyte injury. Kidney Int. 2014;86(2):275–285. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(5):649–658. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cubro H, Kashyap S, Nath MC, Ackerman AW, Garovic VD. The Role of Interleukin-10 in the Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20(4). doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0833-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wegmann TG, Lin H, Guilbert L, Mosmann TR. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a TH2 phenomenon? Immunol Today. 1993;14(7):353–356. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90235-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darmochwal-Kolarz D, Leszczynska-Gorzelak B, Rolinski J, Oleszczuk J. T helper 1-and T helper 2-type cytokine imbalance in pregnant women with pre-eclampsia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;86(2):165–170. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(99)00065-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson KK, Meeker JD, McElrath TF, Mukherjee B, Cantonwine DE. Repeated measures of inflammation and oxidative stress biomarkers in preeclamptic and normotensive pregnancies. In: American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Vol 216. Mosby Inc.; 2017:527.e1–527.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.12.174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore KW, De Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park SH, Kim KE, Hwang HY, Kim TY. Regulatory effect of SOCS on NF-κB activity in murine monocytes/macrophages. DNA Cell Biol. 2003;22(2):131–139. doi: 10.1089/104454903321515931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zemse SM, Chiao CW, Hilgers RHP, Webb RC. Interleukin-10 inhibits the in vivo and in vitro adverse effects of TNF-α on the endothelium of murine aorta. Am J Physiol - Hear Circ Physiol. 2010;299(4). doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00763.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tinsley JH, South S, Chiasson VL, Mitchell BM. Interleukin-10 reduces inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and blood pressure in hypertensive pregnant rats. Am J Physiol - Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298(3). doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00712.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zemse SM, Hilgers RHP, Simkins GB, Rudic RD, Webb RC. Restoration of endothelin-1-induced impairment in endothelium-dependent relaxation by interleukin-10 in murine aortic rings. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;86(8):557–565. doi: 10.1139/Y08-049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunnett CA, Heistad DD, Berg DJ, Faraci FM. IL-10 deficiency increases superoxide and endothelial dysfunction during inflammation. Am J Physiol - Hear Circ Physiol. 2000;279(4 48–4). doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.h1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunnett CA, Heistad DD, Faraci FM. Interleukin-10 protects nitric oxide-dependent relaxation during diabetes: Role of superoxide. Diabetes. 2002;51(6):1931–1937. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.6.1931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunnett CA, Lund DD, Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Vascular interleukin-10 protects against LPS-induced vasomotor dysfunction. Am J Physiol - Hear Circ Physiol. 2005;289(2 58–2). doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01234.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nevers T, Kalkunte S, Sharma S. Uterine regulatory T cells, IL-10 and hypertension. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66(SUPPL. 1):88–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01040.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hennessy A, Pilmore HL, Simmons LA, Painter DM. A deficiency of placental IL-10 in preeclampsia. J Immunol. 1999;163(6):3491–3495. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10477622. Accessed August 27, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahin S, Ozakpinar OB, Eroglu M, et al. The impact of platelet functions and inflammatory status on the severity of preeclampsia. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2015;28(6):643–648. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.927860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinzenbaw DA, Chu Y, Peña Silva RA, Didion SP, Faraci FM. Interleukin-10 protects against aging-induced endothelial dysfunction. Physiol Rep. 2013;1(6):1–8. doi: 10.1002/phy2.149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalkunte S, Boij R, Norris W, et al. Sera from preeclampsia patients elicit symptoms of human disease in mice and provide a basis for an in vitro predictive assay. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(5):2387–2398. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai Z, Kalkunte S, Sharma S. A critical role of interleukin-10 in modulating hypoxia-induced preeclampsia-like disease in mice. Hypertension. 2011;57(3):505–514. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akison LK, Nitert MD, Clifton VL, Moritz KM, Simmons DG. Review: Alterations in placental glycogen deposition in complicated pregnancies: Current preclinical and clinical evidence. Placenta. 2017;54:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.01.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mills JL, DerSimonian R, Raymond E, et al. Prostacyclin and thromboxane changes predating clinical onset of preeclampsia: A multicenter prospective study. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282(4):356–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.4.356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Deursen JM. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature. 2014;509(7501):439–446. doi: 10.1038/nature13193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zemse SM, Hilgers RHP, Webb RC. Interleukin-10 counteracts impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation induced by ANG II in murine aortic rings. Am J Physiol - Hear Circ Physiol. 2007;292(6). doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00456.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Didion SP, Kinzenbaw DA, Schrader LI, Chu Y, Faraci FM. Endogenous interleukin-10 inhibits angiotensin II-induced vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2009;54(3):619–624. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giachini FRC, Zemse SM, Carneiro FS, et al. Interleukin-10 attenuates vascular responses to endothelin-1 via effects on ERK1/2-dependent pathway. Am J Physiol - Hear Circ Physiol. 2009;296(2). doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00251.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sikka G, Miller KL, Steppan J, et al. Interleukin 10 knockout frail mice develop cardiac and vascular dysfunction with increased age. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48(2):128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salazar Garcia MD, Mobley Y, Henson J, et al. Early pregnancy immune biomarkers in peripheral blood may predict preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol. 2018;125:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2017.10.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell N, LaMarca B, Cunningham MW. The Role of Agonistic Autoantibodies to the Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor (AT1-AA) in Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2018;19(10):781–785. doi: 10.2174/1389201019666180925121254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallukat G, Homuth V, Fischer T, et al. Patients with preeclampsia develop agonistic autoantibodies against the angiotensin AT1 receptor. J Clin Invest. 1999;103(7):945–952. doi: 10.1172/JCI4106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brewer J, Liu R, Lu Y, et al. Endothelin-1, oxidative stress, and endogenous angiotensin II: Mechanisms of angiotensin II type i receptor autoantibody-enhanced renal and blood pressure response during pregnancy. Hypertension. 2013;62(5):886–892. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mishra N, Nugent WH, Mahavadi S, Walsh SW. Mechanisms of enhanced vascular reactivity in preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2011;58(5):867–873. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.176602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gant NF, Daley GL, Chand S, Whalley PJ, MacDonald PC. A study of angiotensin II pressor response throughout primigravid pregnancy. J Clin Invest. 1973;52(11):2682–2689. doi: 10.1172/JCI107462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdul-Karim R, Assali NS. Pressor response to angiotonin in pregnant and nonpregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1961;82(2):246–251. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(61)90053-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chesley LC. Vascular reactivity in normal and toxemic pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1966;9(4):871–881. doi: 10.1097/00003081-196612000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weissgerber TL, Milic NM, Milin-Lazovic JS, Garovic VD. Impaired Flow-Mediated Dilation Before, During, and after Preeclampsia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hypertension. 2016;67(2):415–423. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luscher TF, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-dependent contractions to acetylcholine in the aorta of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 1986;8(4):344–348. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.8.4.344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller VM, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-dependent contractions to arachidonic acid are mediated by products of cyclooxygenase. Am J Physiol - Hear Circ Physiol. 1985;17(4). doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.248.4.h432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamilton CA, Berg G, Mcintyre M, Mcphaden AR, Reid JL, Dominiczak AF. Effects of nitric oxide and superoxide on relaxation in human artery and vein. Atherosclerosis. 1997;133(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(97)00114-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cosentino F, Christopher Sill J, Katušić ZS. Role of superoxide anions in the mediation of endothelium-dependent contractions. Hypertension. 1994;23(2):229–235. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.23.2.229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burke SD, Zsengellér ZK, Khankin EV., et al. Soluble FMS-like Tyrosine Kinase 1 promotes angiotensin II sensitivity in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(7):2561–2574. doi: 10.1172/JCI83918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katusic ZS. Superoxide anion and endothelial regulation of arterial tone. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20(3):443–448. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)02116-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kao CK, Morton JS, Quon AL, Reyes LM, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Davidge ST. Mechanism of vascular dysfunction due to circulating factors in women with pre-eclampsia. Clin Sci. 2016;130(7):539–549. doi: 10.1042/CS20150678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberge S, Bujold E, Nicolaides KH. Aspirin for the prevention of preterm and term preeclampsia: systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(3):287–293.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walton RB, Reed LC, Estrada SM, et al. Evaluation of sildenafil and tadalafil for reversing constriction of fetal arteries in a human placenta perfusion model. Hypertension. 2018;72(1):167–176. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cattaruzza M, Słodowski W, Stojakovic M, Krzesz R, Hecker M. Interleukin-10 induction of nitric-oxide synthase expression attenuates CD40-mediated interleukin-12 synthesis in human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(39):37874–37880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301670200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lima VV, Zemse SM, Chiao CW, et al. Interleukin-10 limits increased blood pressure and vascular RhoA/Rho-kinase signaling in angiotensin II-infused mice. Life Sci. 2016;145:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krege JH, Hodgin JB, Hagaman JR, Smithies O. A noninvasive computerized tail-cuff system for measuring blood pressure in mice. Hypertension. 1995;25(5):1111–1115. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.25.5.1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McDowell EM, Trump BF. Histologic fixatives suitable for diagnostic light and electron microscopy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1976;18 OCT-77:405–414. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/60092/. Accessed August 25, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.d’Uscio LV, He T, Santhanam AVR, Tai LJ, Evans RM, Katusic ZS. Mechanisms of vascular dysfunction in mice with endothelium-specific deletion of the PPAR-δ gene. Am J Physiol - Hear Circ Physiol. 2014;306(7). doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00761.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nath KA, Belcher JD, Nath MC, et al. Role of TLR4 signaling in the nephrotoxicity of Heme and heme proteins. Am J Physiol - Ren Physiol. 2018;314(5):F906–F914. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00432.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nath KA, O’brien DR, Croatt AJ, et al. The murine dialysis fistula model exhibits a senescence phenotype: Pathobiological mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Am J Physiol - Ren Physiol. 2018;315(5):F1493–F1499. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00308.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weissgerber TL, Garovic VD, Savic M, Winham SJ, Milic NM. From Static to Interactive: Transforming Data Visualization to Improve Transparency. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(6). doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary methods: Patient sera, Animals and Interventions, qPCR, Electron microscopy, Glycogen deposits in placenta, Vascular reactivity studies

Table S1: Characteristics of patients providing serum samples

Table S2: Aortic COX gene expression analyses in WT and IL-10−/− mice

Figure S1: Fetal characteristics in WT and IL-10−/− mice injected with human NT and sPE sera. Total litter weights (A) and fetal lengths (B) in pregnant female WT and IL-10−/− mice. n = 5 per group. WT indicates wild type; IL-10−/−, interleukin-10 knockout; PG, pregnant; nPG, non-pregnant; NT, normotensive; sPE, severe preeclamptic. Data were analyzed by One-Way ANOVA with least significant differences as post hoc test: Total litter size: F=4.937, df=3, p=0.014 (IL-10−/− PG + NT had lowest total litter weight in comparison to other groups); Fetal length: F=1.500, df=3, p=0.258).

Figure S2: Individual sFlt-1/PlGF ratio values for human serum samples used to inject the animals. There was a significant difference between women with preeclampsia and normotensive women (Table S1).