Abstract

Veterans have high rates of suicide, and nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is one of the strongest predictors of suicide risk; however, there is presently little known about antecedents of NSSI that might inform intervention efforts. Accumulating research suggests that anger and hostility play an important role in NSSI, but whether these emotions precede and predict NSSI is currently unknown. The aim of the current study was to examine the temporal relationships between anger/hostility and NSSI urges and behavior among veterans diagnosed with NSSI disorder. Our hypothesis was that angry/hostile affect would predict subsequent NSSI urge and engagement, but not vice versa. Forty veterans with NSSI disorder completed a 28-day ecological momentary assessment study with three daily prompts to report on their affect and NSSI urges and engagement. Multilevel cross-lagged path modeling was used to determine the direction of effects between angry/hostile affect and NSSI urges and engagement over time. Consistent with our hypothesis, results indicated that the lagged effects of angry/hostile affect on subsequent NSSI urge and engagement were significant, whereas the lagged effects of NSSI urge and engagement on angry/hostile affect were not significant. Findings highlight the importance of assessing and treating anger among veterans who engage in NSSI.

Keywords: nonsuicidal self-injury, anger, hostility, risk factors, ecological momentary assessment, veterans

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is the direct, deliberate destruction of one’s own body tissue without conscious suicidal intent (Nock, 2010). An estimated 5.5% of the general adult population will engage in NSSI during their lifetime, with elevated rates (19–25%) among psychiatric populations (Briere & Gil, 1998; Swannell et al., 2014). A population with particularly high rates of NSSI are veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). For example, in a study of veterans seeking treatment for PTSD, 82% of the sample reported a lifetime history of NSSI and 64% reported engaging in NSSI in the past two weeks (Kimbrel et al., 2018). In addition to inherent physical injury, NSSI is associated with several adverse mental health outcomes (Briere & Gil, 1998; Zetterqvist et al., 2013) and constitutes one of the strongest predictors of future suicide attempts (Franklin et al., 2017; Ribeiro et al., 2016). Despite alarming rates of suicide among veterans (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2018), there is a relative paucity of literature pertaining to understanding their risk for NSSI.

One way to better understand risk for NSSI is through ecological momentary assessment (EMA) studies, which allow researchers to gather data in real-time on emotions, cognitions, and behaviors occurring in participants’ natural environments (Bolger et al., 2003). EMA via mobile technology can be used to examine the affective states that predict subsequent NSSI urges and behaviors, which is crucial for the development of targeted interventions for NSSI. For example, if specific affective states are precursors to NSSI urges and behaviors, patients can learn to identify those triggers in the moment and engage in strategies and coping skills to reduce NSSI risk. Further, EMA can be used as part of interventions (i.e., increases in affect may trigger the device to provide the individual with resources, skills, or support to prevent NSSI). Previous EMA studies among adolescents and young adults have found that NSSI is typically preceded by increased negative affect and decreased positive affect (Andrewes et al., 2017; Kranzler et al., 2018). These findings are consistent with evidence suggesting that a primary function of NSSI is to attempt to regulate emotion (Briere & Gil, 1998; Klonsky, 2011; Zetterqvist et al., 2013).

One emotion that is particularly prevalent and difficult for veterans to regulate is anger. Difficulty controlling anger is the most commonly reported reintegration concern among combat veterans, endorsed by 57–61% of Iraq-Afghanistan veterans in national surveys (Sayer et al., 2010; Sippel et al., 2016). Further, among veterans with PTSD, the prevalence of dysregulated anger is even greater (84%; Sayer et al., 2010); however, few EMA studies have examined the associations between anger and NSSI. Notably, Nock and colleagues (2009) utilized EMA to study NSSI in a sample of adolescents and young adults (13.3% male) with a history of NSSI and found that increases in anger/hostility-related emotions (i.e., anger toward oneself, anger toward another, feeling rejected, self-hatred) were associated with NSSI behavior, whereas feeling sad/worthless was negatively associated with NSSI and feeling scared/anxious or overwhelmed was not related to NSSI behavior. Armey and colleagues (2011) used EMA to model changes in affect before, during, and after NSSI behavior among college students (25% male) with a history of NSSI. They found that negative affect, particularly anger, loathing, and guilt, had a quadratic relationship with instances of NSSI, increasing in the hours prior to engagement and decreasing afterwards. Taken together, anger-related emotions have been associated with NSSI in EMA studies. However, prior EMA studies of NSSI have been limited to civilian populations that were largely comprised of female participants. More work is needed to elucidate the temporal relationship between anger and NSSI in veteran samples.

NSSI disorder was included in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) as a “disorder for future study.” In prior versions of the DSM, NSSI had been included only as a symptom of borderline personality disorder. There is now considerable evidence that it is a transdiagnostic phenomenon that can occur even in the absence of another psychiatric disorder, though it is most strongly associated with PTSD and panic disorder (Bentley et al., 2015). To meet diagnostic criteria for NSSI disorder, an individual must engage in NSSI on five or more days in the past year with an expectation that it will relieve negative thoughts/feelings, resolve an interpersonal difficulty, and/or create a positive feeling. Additionally, the NSSI must be preceded by negative thoughts/feelings or interpersonal problems, a preoccupation with the behavior that is difficult to resist, and/or frequent urges to engage in NSSI. Finally, the behavior cannot be socially sanctioned and must cause significant distress or impairment. Initial evidence of NSSI disorder has supported its validity as an independent and distinct disorder, distinguishable from other disorders and associated with significant distress and impairment (Zetterqvist, 2015).

The aim of the present study was to examine the temporal relationships between anger/hostility and NSSI among veterans diagnosed with NSSI disorder. To our knowledge, no prior study has utilized EMA methods to study NSSI in a sample comprised exclusively of individuals with NSSI disorder, nor has any prior EMA study of NSSI utilized a veteran sample, or a sample in which the majority of participants were adult men. In addition, to our knowledge, no prior study has utilized cross-lagged analyses to study the directional relationship between anger/hostility and NSSI. Determining whether anger/hostility precedes and predicts NSSI is the necessary next step to develop targeted interventions for this population. Accordingly, using multilevel cross-lagged path models, we tested our hypothesis that previous anger/hostility would predict subsequent NSSI thoughts and behaviors, but not vice versa.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Forty veterans with NSSI disorder were recruited to complete a 28-day electronic diary study. This was a sub-study of a larger project focused on studying the impact of NSSI on veterans’ functional outcomes. Potential participants were contacted via mailings targeting veterans who had sought care in VA PTSD clinics or had agreed to be listed in research recruitment databases. To be eligible for the parent study, participants had to be veterans, 18 years or older, with at least one psychiatric disorder. Exclusion criteria were lifetime bipolar or psychotic spectrum disorder or imminent risk for suicide (based on the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale [C-SSRS; Posner et al., 2008]) or homicide (using a brief interview). Overall, 155 potential participants attended an in-person screening visit and 31 were excluded, for a total sample size of 124 in the parent study. Reasons for exclusion were: bipolar or psychotic spectrum disorder (n = 19), unable/unwilling to complete study procedures (n = 10), no recent history of NSSI (n = 1)1, no lifetime or current psychiatric diagnoses (n = 1).

Participants with a current diagnosis of NSSI disorder who were willing to complete the EMA procedures were recruited for the current sub-study. Forty-one participants from the parent study were diagnosed with NSSI disorder and one declined to complete the EMA procedures, yielding a sample size of 40 for the current study. All study procedures were approved by the Durham VA Institutional Review Board (IRB) and Research and Development Committee. See Table 1 for participant demographics and clinical characteristics. Notably, the majority of participants also met criteria for PTSD (lifetime prevalence = 95%) and major depressive disorder (lifetime prevalence = 95%).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Diary Descriptors

| Participant Demographics | Mean (SD) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 46.65 (12.76) | |

| Female | 11 (27.5%) | |

| Race | ||

| Black | 22 (55.0%) | |

| White | 18 (45.0%) | |

| Diary Descriptors | ||

| Entries per person | 43.75 (14.04) | |

| NSSI engagement | 163 (9.3%) | |

| NSSI urges | 330 (18.8%) | |

| Angry affect | 1.22 (1.20) | |

| Hostile affect | 0.79 (0.97) |

Note. Diary descriptors are based on readings available for the present analyses (i.e., those occurring within 6 hours of a previous reading and with no missing data for angry affect, hostile affect, NSSI engagement, or NSSI urge).

Measures

Diagnostic Measures

NSSI disorder was assessed using the Clinician Administered Nonsuicidal Self-injury Disorder Index (CANDI; Gratz et al., 2015). The CANDI exhibits good interrater reliability (k = .83) and adequate internal consistency (α = .71; Gratz et al., 2015). The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5; First, Williams, Karg, & Spitzer, 2016) was used to assess other psychiatric disorders. Masters-level clinicians were required to complete extensive training procedures prior to conducting interviews independently, including studying interview manuals, watching instructional training videos, rating videotaped interviews, and participating in ongoing weekly supervision. Because NSSI disorder was the focus of the study, each CANDI was discussed in diagnostic review groups led by a licensed clinical psychologist until diagnostic consensus was reached for each case.

Ecological Momentary Assessment Procedures

Participants were provided with an Android smartphone for 28 days of EMA data collection. During a training session, the participant set a 14-hour wake period and a 10-hour sleep period during which the alarmed prompts would be active and inactive, respectively. Participants received three random alarms per day (approximately every four hours) in which they were prompted to answer a series of questions related to their affective state, current activity and setting, and whether they had engaged in NSSI or had experienced an urge to do so in the past four hours. Participants were also asked to initiate a diary entry when they engaged in NSSI or felt the urge to do so. Items from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form (PANAS-X; Watson & Clark, 1999) were used to assess affect. Among other affective states, participants rated the extent to which they felt angry and hostile during the past four hours on a scale of 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely). Anger and hostility are related constructs that are highly correlated (Eckhardt et al., 2004). Whereas anger is defined as an emotional state—often in response to a thwarted goal or perceived threat—hostility refers to a general predisposition to dislike and mistrust others (Eckhardt et al., 2004). Hostility is often considered a cognitive component of anger.

To quantify the association between angry and hostile affect, we used multilevel modeling to regress angry affect on hostile affect and calculated the pseudo-R2 using Snijders and Bosker’s (1999) method. According to that analysis, hostile affect explained 58.9% of the between-person variance in angry affect and 47.2% of the within-person variance, corresponding to equivalent correlations of .77 and .69, respectively. A combined angry and hostile score (angry/hostile) was created by taking the mean of the two items.

Participants were compensated according to their compliance with the EMA procedures: They received $250 for completion of 75–100% of the prompted diaries, $170 for 50–74%, $100 for 25–49%, and $50 for 0–25%. This resulted in high rates of compliance (81.6%) and a mean of 68.57 (SD = 16.54) prompted diary entries over the study. When including self-initiated entries as well, participants completed a mean of 86.35 (SD = 15.90) entries. Demographic (i.e., age, gender, race) and clinical variables (i.e., PTSD or MDD status) were not associated with number of diaries completed (p-values > .09).

Data Analysis

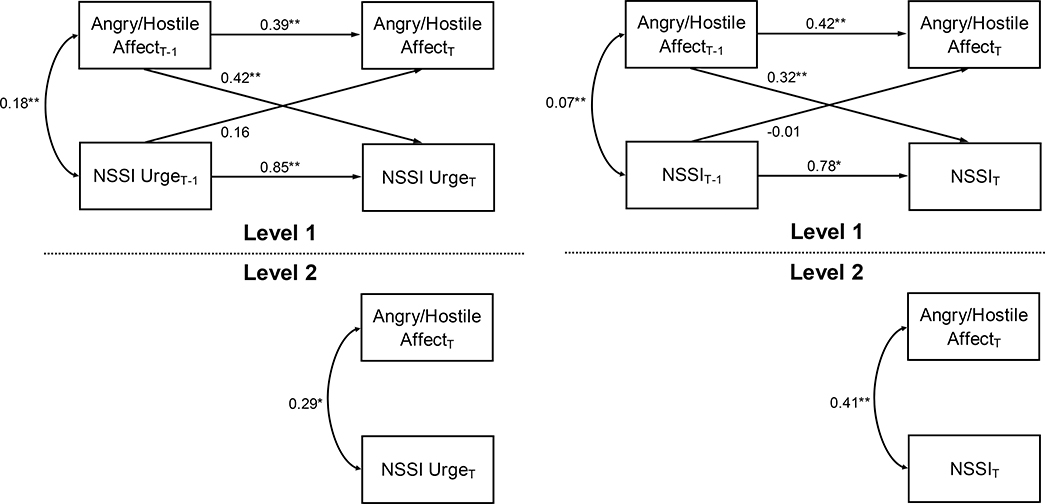

To determine the direction of the association of angry/hostile affect with NSSI urges and engagement over time, we used multilevel cross-lagged path modeling. Multilevel modeling was appropriate because our data were characterized by two levels of observations: those made at the level of each diary reading (Level 1) and those made at the level of each participant (Level 2). With path analysis, we could examine not only the autoregressive effects of angry/hostile affect and NSSI urge and engagement but also whether previous angry/hostile affect predicted subsequent NSSI urge and engagement, as well as whether previous NSSI urge and engagement predicted subsequent angry/hostile affect.

Cross-lagged analysis of NSSI urges and engagement were examined in separate path models. In both models, autoregressive effects and cross-lagged effects were examined. Wald chi-square tests were used to test the hypothesis that the lagged effects of angry/hostile affect on subsequent NSSI urge and engagement would be stronger than the lagged effects of NSSI urge and engagement on subsequent angry/hostile affect. Analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 and Mplus 7 using robust maximum likelihood method, which could accommodate the combination of continuous (angry/hostile affect) and dichotomous (NSSI urge and engagement) outcomes. Only readings that occurred no more than six hours apart, representing 62.6% of all readings, were used.

Results

Participant and electronic diary descriptors are summarized in Table 1. NSSI engagement was reported in 9.3% of diary entries, whereas NSSI urge was reported in 18.8% of entries. The most common type of NSSI was punching walls/objects (39.6%), followed by punching or hitting oneself (26%), biting (20.8%), scratching (18.8%), cutting (13.2%), banging head (6.9%), and burning (1%). Approximately 39.3% of reports of NSSI urge overlapped with a concurrent report of NSSI engagement.

The results of the fully crossed NSSI urge and engagement path models are depicted in Figure 1. In support of our hypothesis, the lagged effect of angry/hostile affect on subsequent NSSI urge was significant, whereas the lagged effect of NSSI urge on subsequent angry/hostile affect was not significant. Moreover, the Wald test indicated that the contrast between cross-lagged effects was significant, X2(1) = 6.56, p = .010. In the model of NSSI engagement, we similarly found that the lagged effect of angry/hostile affect on NSSI engagement was significant, whereas the lagged effect of NSSI engagement on angry/hostile affect was not significant. Additionally, the Wald test was significant, X2(1) = 5.32, p = .021, indicating that the two cross-lagged effects were significantly different.

Figure 1.

Cross-Lagged Path Models

Note. Cross-lagged path models of angry/hostile affect, NSSI urge, and NSSI engagement. Level 1 represents within-person relationships, Level 2 between-person relationships. NSSI urge and engagement are dichotomous variables; thus, corresponding path coefficients may be exponentiated to produce odds ratios.

Discussion

This study used EMA and multilevel cross-lagged path modeling to evaluate the temporal relationships between anger/hostility and NSSI among veterans. Our hypothesis was that anger/hostility would predict subsequent NSSI urges and behaviors, but not vice versa. Results confirmed this hypothesis: The effects of angry/hostile affect on subsequent NSSI urge and engagement were significant, whereas the effects of NSSI urge and engagement on subsequent angry/hostile affect were not. These findings are the first to demonstrate the direction of effects and highlight momentary anger/hostility as a prospective predictor of NSSI urges and behavior among veterans with NSSI disorder.

Emerging evidence, including the results of this study, highlight the important role of dysregulated anger in dangerous self-harming behaviors (e.g., Dobscha et al., 2014; Novaco et al., 2012). Dysregulated anger is a well-documented problem in the U.S. veteran population with one study indicating that 61.2% of US veterans report difficulty controlling their anger (Sippel et al., 2016). However, despite literature suggesting dysregulated anger is present in a range of emotional (e.g., mood, anxiety) disorders, it is a diagnostic criterion in relatively few disorders (e.g., PTSD, borderline personality disorder) and thus is not consistently assessed (Cassiello-Robbins & Barlow, 2016). Consistent assessment of anger and anger-related difficulty in veterans is likely warranted to fully understand their mental health functioning.

It is likely that NSSI is used as a maladaptive coping strategy for veterans who struggle to regulate their anger/hostility. Indeed, the most commonly cited function of NSSI is an intrapersonal negative-reinforcement function to reduce the intensity of strong emotions (Taylor et al., 2018). Overall, results of this study suggest interventions that target emotion regulation and/or distress tolerance are likely needed to help veterans manage experiences of elevated anger/hostility. In the VA, problematic anger is typically treated with group-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and, although there is evidence to support this treatment modality, there have been very few controlled trials of CBT for anger in this population (see Van Voorhees et al., 2020). Evidence-based anger management strategies may help not only reduce the distress of anger, but also reduce NSSI behavior in veterans, and additional research is needed exploring the effectiveness of such interventions for this population.

Notably, to our knowledge, the present study is first to utilize EMA to study the relationship between anger/hostility and NSSI among veterans with NSSI disorder. Given the prevalence of NSSI among veterans and the relationship between NSSI and suicide, this study represents an important contribution; there are, however, a few limitations that should also be noted. First, the small sample size limits the generalizability of our findings to the broader population of veterans with NSSI disorder. Furthermore, the majority (95%) of the sample had lifetime diagnosis of comorbid PTSD and/or MDD and the sample was mostly male (72.5%), which limits the extent to which our findings may generalize to women veterans or those without comorbid PTSD or MDD. Second, although the current study allowed us to examine the temporal relationship between anger/hostility and subsequent NSSI urges and behaviors, the time frame between assessments analyzed was relatively large (up to 6 hours), and there were only three prompted diaries per day. This limits our ability to determine how quickly changes in anger/hostility contribute to NSSI urges and behaviors. In future research, it may be important to use more frequent assessments to further clarify the time course of momentary anger in the prediction of subsequent NSSI urges or behaviors. Third, it is possible that instances of NSSI urges or behaviors that occurred during the 10-hour nighttime period may have been missed. Participants were asked during the nightly diary whether there had been any instances of urges or behaviors that day that had not already been reported, but there was not a morning diary to assess this during the night. Fourth, the use of one-word items to assess affective states on a simple 0–4 scale was important to reduce participant burden and improve compliance; however, it is possible that there were individual differences in the ways that these items were interpreted by the participants that may have influenced the results and this brief assessment may have been inadequate to capture the multi-dimensionality of these constructs. Further, the recipient of anger was unassessed so it is unclear to what extent participants were experiencing anger at themselves versus anger at others. Different targets of anger may be differentially related to NSSI urges and behaviors. Future research using established measures of anger and hostility and incorporating additional indices of affective states (both positive and negative emotions) is needed. Additionally, given prior research implicating the role of other emotional states (e.g., guilt, shame; Sheehy et al., 2019) and situations (e.g., problematic interpersonal relationships; Levesque et al., 2010) in NSSI, future research should examine whether these constructs are precursors to NSSI urges and behaviors in veterans with NSSI disorder. Future research should also examine whether anger/hostility is differentially related to more aggressive manifestations of NSSI (e.g., punching).

In sum, results from the current study indicate that momentary increases in angry/hostile affect predict and precede NSSI urges and behaviors in veterans with NSSI disorder. These findings further highlight the importance of assessing dysregulated anger in veterans who self-injure, as well as the potential utility of anger management interventions to reduce NSSI and associated negative outcomes. Such efforts are important among veterans, a group particularly at risk for suicide (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Merit Award #I01CX001486 to Dr. Kimbrel from the Clinical Sciences Research and Development Service (CSR&D) of VA Office of Research and Development (VA ORD). Manuscript preparation was partially supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment (Drs. Glenn & Gromatsky). Dr. Dillon was supported by a Career Development Award (IK2RX002965) from the Rehabilitation Research and Development Service of VA ORD. Manuscript preparation for Dr. LoSavio was supported by a grant from the Clinical Sciences Research & Development Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research Development (1I01CX001757). Dr. Beckham was supported by a Senior Research Career Scientist award (1K6BX003777) from the CSR&D of VA ORD. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the VA or the United States government or any of the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

Footnotes

This individual was excluded early in the study when recent NSSI was an inclusion criteria for the parent study. These criteria were later amended.

References

- Andrewes HE, Hulbert C, Cotton SM, Betts J, & Chanen AM (2017). An ecological momentary assessment investigation of complex and conflicting emotions in youth with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research, 252, 102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armey MF, Crowther JH, & Miller IW (2011). Changes in ecological momentary assessment reported affect associated with episodes of nonsuicidal self-injury. Behavior Therapy, 42, 579–588. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley KH, Cassiello-Robbins CF, Vittorio L, Sauer-Zavala S, & Barlow DH (2015). The association between nonsuicidal self-injury and the emotional disorders: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 72–88. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, & Rafaeli E (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, & Gil E (1998). Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: Prevalence, correlates, and functions. American journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68, 609–620. 10.1037/h0080369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassiello-Robbins C, & Barlow DH (2016). Anger: The unrecognized emotion in emotional disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 23, 66–85. 10.1111/cpsp.12139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (2018). Veteran Suicide Data Report, 2005–2016. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/OMHSP_National_Suicide_Data_Report_2005-2016_508-compliant.pdf

- Dobscha SK, Denneson LM, Kovas AE, Teo A, Forsberg CW, Kaplan MS, … & McFarland BH (2014). Correlates of suicide among veterans treated in primary care: Case–control study of a nationally representative sample. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29, 853–860. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-014-3028-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, & Spitzer RL (2015). Structured clinical interview for DSM-5—Research version (SCID-5-RV). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 1–94. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, … & Nock MK (2017). Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 143, 187–232. doi: 10.1037/bul0000084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Dixon-Gordon KL, Chapman AL, & Tull MT (2015). Diagnosis and characterization of DSM-5 nonsuicidal self-injury disorder using the clinician-administered nonsuicidal self-injury disorder index. Assessment, 22, 527–539. doi: 10.1177/1073191114565878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, Thomas SP, Hicks TA, Hertzberg MA, Clancy CP, Elbogen EB, … Silvia PJ (2018). Wall/object punching: an important but under-recognized form of nonsuicidal self-injury. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 48, 501–511. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED (2011). Non-suicidal self-injury in United States adults: prevalence, sociodemographics, topography and functions. Psychological Medicine, 41, 1981. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler A, Fehling KB, Lindqvist J, Brillante J, Yuan F, Gao X, … & Selby EA (2018). An ecological investigation of the emotional context surrounding nonsuicidal self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in adolescents and young adults. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 48, 149–159. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque C, Lafontaine MF, Bureau JF, Cloutier P, & Dandurand C (2010). The influence of romantic attachment and intimate partner violence on non-suicidal self-injury in young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 474–483. DOI: 10.1007/s10964-009-9471-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK (2010). Self-injury. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 339–363. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ, & Sterba SK (2009). Revealing the form and function of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A real-time ecological assessment study among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 816–827. doi: 10.1037/a0016948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novaco RW, Swanson RD, Gonzalez OI, Gahm GA, & Reger MD (2012). Anger and postcombat mental health: Validation of a brief anger measure with US Soldiers postdeployed from Iraq and Afghanistan. Psychological Assessment, 24, 661–675. 10.1037/a0026636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C, Gould M, Stanley B, Brown G, … & Mann J (2008). Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS). New York, NY: Columbia University Medical Center. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Chang BP, & Nock MK (2016). Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine, 46, 225–236. doi: 10.1017/s0033291715001804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer NA, Noorbaloochi S, Frazier P, Carlson K, Gravely A, & Murdoch M (2010). Reintegration problems and treatment interests among Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans receiving VA medical care. Psychiatric Services, 61, 589–597. 10.1176/ps.2010.61.6.589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehy K, Noureen A, Khaliq A, Dhingra K, Husain N, Pontin EE, … & Taylor PJ (2019). An examination of the relationship between shame, guilt and self-harm: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 73, 101779. 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippel LM, Mota NP, Kachadourian LK, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, Harpaz-Rotem I, & Pietrzak RH (2016). The burden of hostility in US Veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Psychiatry Research, 243, 421–430. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders T, & Bosker R (1999). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London: Sage Publications. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2013.797841 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, & St John NJ (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44, 273–303. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor PJ, Jomar K, Dhingra K, Forrester R, Shahmalak U, & Dickson JM (2018). A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 759–769. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees EE, Dillon KH, Wilson SM, Dennis PA, Neal LC, Medenblik AM, … & White JD (2019). A comparison of group anger management treatments for combat veterans with PTSD: Results from a quasi-experimental trial. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10.1177/0886260519873335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, & Clark LA (1999). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form. doi: 10.17077/48vt-m4t2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zetterqvist M, Lundh LG, Dahlström Ö, & Svedin CG (2013). Prevalence and function of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in a community sample of adolescents, using suggested DSM-5 criteria for a potential NSSI disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 759–773. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9712-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]