Abstract

Introduction

An effective strategy to manage acute pain while minimizing opioid exposure is needed for injured patients. In this trial, we aimed to compare two multimodal pain regimens (MMPR) in minimizing opioid exposure and relieving acute pain in a busy, urban trauma center.

Methods

This was an unblinded, pragmatic, randomized, comparative effectiveness trial of all adult trauma admissions except vulnerable patient populations and readmissions. The original MMPR (intravenous administration, followed by oral, acetaminophen, 48 hours of celecoxib and pregabalin followed by naproxen and gabapentin, scheduled tramadol, and as needed oxycodone) was compared to a MMPR with generic medications, termed the MAST MMPR (oral acetaminophen, naproxen, gabapentin, lidocaine patches, and as needed opioids). The primary outcome was oral morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day and secondary outcomes included total MME during hospitalization, opioid prescribing at discharge, and pain scores.

Results:

During the trial, 1,561 patients were randomized and included – 787 to the original MMPR and 774 the MAST MMPR. There were no differences in demographics, injury characteristics, or operations performed. Patients randomized to the MAST MMPR had lower MME per day (34 MME/day, IQR [15, 61] versus 48 MME/day, IQR [22,74], p<0.001) and fewer were prescribed opioids at discharge (62% versus 67%, p=0.029; RR 0.92, 95% credible interval 0.86-0.99, posterior probability RR<1 = 0.99). No clinically significant difference in pain scores were seen.

Conclusion:

The MAST MMPR was a generalizable and widely available approach that reduced opioid exposure after trauma and achieved adequate acute pain control.

Keywords: opioid, trauma, acute pain, multimodal pain regimen, opioid exposure

Precis

In trauma patients, a multimodal pain regimen of acetaminophen, naproxen, gabapentin, lidocaine patches, and opioids as needed reduced opioid exposure and discharge from the hospital with an opioid prescription while achieving similar pain control.

Introduction

Trauma patients are particularly vulnerable to developing an opioid use disorder.(1) They often have multi-system injuries and require multiple procedures resulting in acute pain that cannot be adequately managed by regional anesthesia or alternative non-systemic pain control strategies.(2) Multi-modal pain regimens (MMPR) are increasingly used to reduce opioid exposure, effectively address acute pain, and enhance recovery after surgery.(3-7) However, the optimal MMPR for trauma patients is unknown. The ideal MMPR for trauma patients must allow individualized treatment, achieve adequate acute pain control while minimizing opioid use, and be easily implemented. It also must be widely available, cost conscious, and safe for different populations and locales.

In 2013, our trauma center implemented a pill-based MMPR to decrease opioid exposure. This strategy used a fixed schedule of acetaminophen, gabapentinoids, non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), lidocaine patches, and tramadol with stronger opioids available for breakthrough pain. This MMPR reduced opioid exposure by 31% with a small, but significant reduction in patient-reported Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) pain scores.(8) However, this strategy was not opioid-minimizing (with tramadol administered on a fixed dosing schedule) and involved drugs that were more costly (e.g. intravenous acetaminophen) and not widely available in hospital formularies or widely covered by insurance at discharge (e.g. celecoxib and pregabalin).

Partly for these reasons, we conducted the Multi-modal Analgesic Strategies in Trauma (MAST) Trial and hypothesized that the original MMPR would result in lower opioid exposure compared to the widely available, generic MAST MMPR.

METHODS

The MAST Trial was a pragmatic, randomized, comparative effectiveness trial comparing the original MMPR to the MAST MMPR. Its rationale and design have been previously detailed.(9) Institutional Review Board approval was obtained on March 2, 2018. Enrollment occurred between April 2, 2018 and March 31, 2019.

Trial Design

The trial was conducted at the Red Duke Trauma Institute at Memorial Hermann Hospital-Texas Medical Center, the primary teaching hospital for the McGovern Medical School at UT Health. All eligible patients admitted to the adult trauma service were randomized in a 1:1 allocation ratio stratified by unit of admission (trauma ward [ward], intermediate care unit [IMU], or intensive care unit [ICU]) to the original MMPR or MAST MMPR.

Randomization

Eligible patients were randomized in the emergency department by trauma surgery residents upon determination of the unit to which they would be admitted. Residents received the computer-generated randomization allocation from research personnel, available 24/7, and ordered the MMPR using a standardized electronic order set.

Participants

Every patient (≥16 years) admitted to the adult trauma service was screened for enrollment. Pregnant women, prisoners, and re-admissions were excluded. Waiver of consent for randomization was approved as allowed under 45 CFR 46.116 for this minimal risk, comparative effectiveness trial that otherwise would not have been practicable to avoid major selection biases. However, the consent of patients was required to utilize protected health information and include their data in the analysis.

Interventions

The original MMPR consisted of five classes of medication administered on a fixed dosing schedule (Table 1). Acetaminophen was provided intravenously upon admission. Once a patient was able to take pills by mouth (or at 24 hours, whichever was earlier), intravenous acetaminophen was changed to oral acetaminophen. If not contraindicated, a single dose of ketorolac was administered in the emergency department. Celecoxib was scheduled for the next 48 hours and then transitioned to scheduled naproxen. Pregabalin was administered for the first 48 hours, after which the patient was transitioned to gabapentin, titrated as needed. Oral tramadol and lidocaine patches were also components of the fixed dosing schedule. Pure opioid formulations (e.g. oxycodone, hydromorphone, fentanyl, etc...) were used as needed for breakthrough pain.

Table 1:

Treatment Strategy

| Group, medication schedule |

|---|

| Original MMPR |

| Acetaminophen 1 g IV q6 hrs x 24 hrs, followed by acetaminophen 1 g PO q6 hrs thereafter |

| Celecoxib 200 mg PO q6 hrs x 48 hrs, followed by naproxen 500 mg PO q12 hours thereafter |

| Pregabalin 100 mg PO q8 hrs x 48 hrs, followed by gabapentin 300 mg PO q8 hrs thereafter |

| Lidocaine patch q12 hrs |

| Tramadol 100 mg PO q6 hrs |

| Opioid as needed |

| MAST MMPR |

| Acetaminophen 1 g PO q6 hrs |

| Naproxen 500 mg PO q12 hrs |

| Gabapentin 300 mg PO q8 hrs |

| Lidocaine patch q12 hrs |

| Opioid as needed |

The original MMPR and the MAST MMPR were given according to the schedule of medication listed above. In addition to this medication, pure formulations of opioids were prescribed as needed for breakthrough pain or per bedside physician discretion.

MAST, Multimodal Analgesic Strategies in Trauma; MMPR, multimodal pain regimen.

The MAST MMPR included a single dose of ketorolac (if not contraindicated) and a fixed dosing schedule of oral acetaminophen, naproxen, gabapentin, and lidocaine patches. Pure opioid formulations were used as needed for breakthrough pain. The responsible physicians in this pragmatic trial were free to alter pain management as needed, without limitation to both avoid overtreatment of acute pain when minimal and ensure adequate acute pain control when not. Both MMPRs were part of an acute pain protocol which determine dose modifications and contraindications for conditions such as liver disease (acetaminophen), seizures (tramadol), and acute kidney injury (gabapentinoids and NSAIDs). More information regarding the acute pain protocol can be found at https://med.uth.edu/surgery/acute-trauma-pain-multimodal-therapy/.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was opioid exposure defined as oral morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day. MME/day was calculated by converting all sources of opioids during the hospital stay, including emergency department and operating room, to a single MME value using a standardized conversion chart and dividing by length of hospital stay.(9) MME/day was chosen as the value can be easily calculated by other centers with which to compare their patients’ opioid exposure and the value accounts for length of stay. Two secondary opioid exposure outcomes included total MME and discharge from the hospital with an opioid prescription.

Another secondary outcome was the mean pain score reported. The Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) reflects the patient’s self-reported level of pain (0=no pain, 10=worst pain). The Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS) is a three-dimensional scale (3-12 with higher scores indicating worse pain) used in non-verbal patients. The scores were recorded by nursing staff during usual clinical care and abstracted directly from the electronic medical record.

Additional secondary outcomes included the incidence of opioid-related complications (e.g., ileus, unplanned intubation, unplanned admission to an intensive care unit, and use of an opioid-reversal agent), complications graded using the Adapted Clavien-Dindo in Trauma (ACDiT) scale, and lengths of stay (hospital, ICU, and ventilator days).(10) The ACDiT is a standardized method to grade the severity of complications following injury. It evaluates complications on a scale ranging from 0 to 5, with 0 indicating no complications and 5 death.

Sample Size

The mean and standard deviation for opioid exposure for patients eligible for this trial could not be estimated accurately when the trial was designed. Partly for this reason, a predetermined study period (one year) rather than a predetermined sample size was used to avoid bias in discontinuing enrollment. We estimated 167 admissions to the adult trauma surgery service each month and aimed to enroll 75% of those patients or 1,506 patients in the 12-month period. In addition to conducting the largest trial feasible in the one year recruitment period, we utilized Bayesian statistical inference to estimate of the probability that the hypothesis is true, (that the original MMPR confers benefit over MAST MMPR). This probability cannot be estimated using conventional, Frequentist analyses.

Blinding

Providers could not be blinded to treatment allocation. However, medication regimens were ordered by clinicians, captured in the electronic medical record as part of regular clinical practice, and queried by research personnel after discharge. Pain scores were collected by nurses in usual clinical practice and similarly queried by research personnel after discharge. The majority of the outcomes were obtained from our institutional trauma registry maintained by independent, trained data entry professionals using definitions standardized by the National Trauma Data Bank.(11, 12) Complications were identified and assigned ACDiT scores by trained research personnel.

Statistical Methods

Analyses utilized an intention-to-treat approach for all eligible randomized patients. Presentation of baseline variables and outcomes employed median (interquartile range) for continuous data and number (percentage) for categorical data.

Bayesian analyses were used to assess the probability of benefit for the primary and secondary outcomes.(13, 14) Bayesian posterior probabilities are statements regarding the probability that the alternative hypothesis is true given the observed data.(15) This focus on the probability that the alternative hypothesis is true, which is simply not available in conventional Frequentist analyses, maps more directly onto the question in clinical decision-makers have which is, “Given what we know what are the chances this approach will confer benefit or harm?”(16-18) Bayesian generalized linear models with extremely vague priors and robustness to prior assumptions was checked by examining alternative priors (Extremely Vague Neutral Priors ~Normal(mean = 0, S.D. = 1000) for coefficients within the respective model’s link function). Additional statistical details are in the eDocument 1.

We planned to use Bayesian modelling for MME/per day to provide a treatment effect after covarying for the stratification variable; however, no parametric model fit the MME/day data and thus none could be provided. For this reason, MME/day outcomes were compared using a stratified Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test applying the Hodges and Lehmann alignment method.(19-21) All other analyses remained Bayesian as planned. Total MME data required zero-inflated negative binominal modelling with results presented as estimated marginal means for ease of interpretation. Estimated marginal means are the mean total MME controlling for unit of admission based upon the Bayesian models.

Analyses used SAS v. 9.4 for non-parametric approaches and R v. 3.6.3 with Stan v. 2.17 for Bayesian models.(22-24)

RESULTS

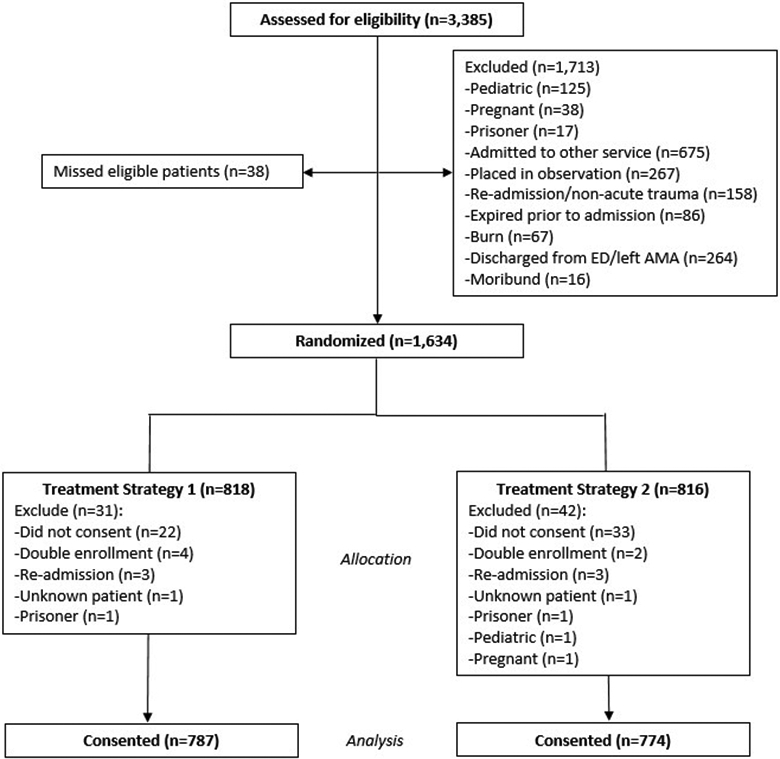

Over the 12-month period, 3,385 patients were screened for eligibility; 34 eligible patients were not included; 1,634 were randomized; 73 were excluded after randomization (almost all because they refused consent or were ineligible for the trial); and 1,561 were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). Patients had a median age of 45 years [IQR 29, 63], 68% were male, 29% were smokers, 12% reported a history of prior opioid use, and 24% had a positive urine drug screen on admission (Table 2). The populations of the original and MAST MMPRs were similar in demographics, medical history, and injury characteristics.

Figure 1:

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram for the Multimodal Analgesic Strategies in Trauma Trial. Of 3,385 screened patients, 1,634 were randomized. The primary reason for exclusion after randomization was refusal of consent to the use of protected health information (n = 55 [3%]). An additional 18 patients (1%) were excluded for double enrollment, readmission, incorrect patient identifier resulting in unknown enrolled patient, or identification of a vulnerable patient status. AMA, against medical advice; ED, emergency department

Table 2:

Patient Demographic and Injury Characteristics

| Demographic and injury characteristic |

Original MMPR (n = 787) |

MAST MMPR (n = 774) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 44 (29–63) | 45 (28–62) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 248 (32) | 252 (33) |

| Male | 539 (68) | 522 (67) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Black | 140 (18) | 167 (22) |

| Hispanic | 264 (34) | 223 (29) |

| Other | 20 (3) | 21 (3) |

| White | 363 (46) | 363 (47) |

| Previous opioid use, n (%) | ||

| No | 690 (88) | 685 (89) |

| Yes | 65 (8) | 52 (7) |

| Unknown | 32 (4) | 37 (5) |

| Smoking history, n (%) | ||

| No | 520 (66) | 524 (68) |

| Yes | 243 (31) | 217 (28) |

| Unknown | 24 (3) | 33 (4) |

| Positive alcohol screen, n (%) | ||

| No | 459 (58) | 474 (61) |

| Yes | 118 (15) | 130 (17) |

| Not performed | 210 (27) | 170 (22) |

| Positive urine drug screen, n (%) | ||

| No | 319 (41) | 316 (41) |

| Yes | 175 (22) | 202 (26) |

| Not performed | 293 (37) | 256 (33) |

| Injury scoring, median (IQR) | ||

| AIS head | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) |

| AIS chest | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–2) |

| AIS abdomen | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) |

| ISS | 14 (9–22) | 14 (9–22) |

| Injury characteristic, n (%) | ||

| Rib fracture | 364 (46) | 356 (46) |

| Rib fracture, median (IQR) | ||

| All patients | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–4) |

| Patient with ≥1 | 4 (2–7) | 4 (2–7) |

| Flail segment, n (%) | 47 (6) | 57 (7) |

| Long bone fracture, n (%) | 252 (32) | 249 (32) |

| Vertebral body fracture, n (%) | 136 (17) | 144 (19) |

| Pelvis or acetabulum fracture, n (%) | 142 (18) | 143 (18) |

| Traumatic brain injury, n (%) | 158 (20) | 147 (19) |

| Unit of admission, n (%) | ||

| Floor | 305 (39) | 280 (36) |

| Intermediate unit | 186 (24) | 194 (25) |

| ICU | 273 (35) | 279 (36) |

| Other | 23 (3) | 21 (3) |

| Procedure, n (%) | ||

| Laparotomy | 96 (12) | 86 (11) |

| Thoracotomy | 35 (4) | 29 (4) |

| Amputation | 9 (1) | 12 (2) |

AIS, Abbreviated Injury Scale; IQR, interquartile range; ISS, Injury Severity Score

Opioid Exposure

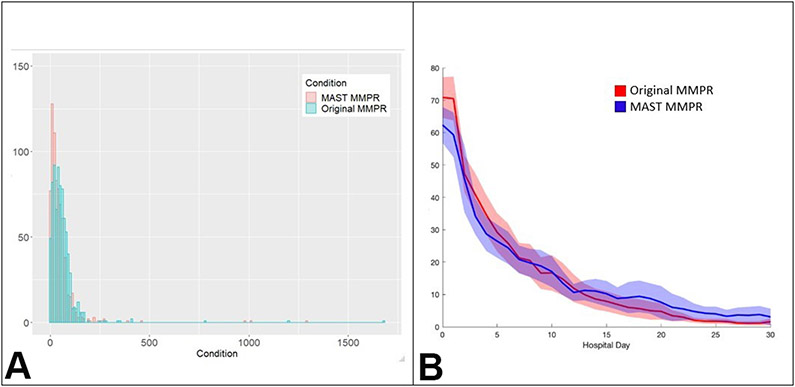

The overlaid histograms for of observed MME/day for both groups are provided in Figure 2 to show the relative distribution of the primary outcome. Patients randomized to the MAST MMPR had lower daily opioid exposure (34 MME/day, IQR [15, 61] versus original MMPR 48 MME/day, IQR [22,74], p<0.001) (Table 3). No interaction between MME/day and unit of admission was seen (p=0.77). Again, no parametric model fit the MME/day data and thus non-parametric results were presented.

Figure 2:

Morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day by treatment group and by hospital day. (A) Histogram of MME per day by multimodal pain regimen (MMPR) treatment group. (B) Average MME/day of patients per hospital day by MMPR treatment group. MAST, Multimodal Analgesic Strategies in Trauma.

Table 3.

Opioid Exposure, Pain Score, and Discharge Opioid Prescribing

| Opioid outcomes | Original MMPR (n = 787) |

MAST MMPR (n = 774) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid exposure and prescribing | |||

| MME/day, median (IQR) | 48 (22–74) | 34 (15–61) | <0.001 |

| Total MME, median (IQR) | 218 (93–490) | 164 (59–450) | <0.001 |

| Opioid at discharge, n (%) | 527 (67) | 476 (62) | 0.039 |

| Opioid, n (%) | |||

| Tramadol | 466 (88) | 427 (90) | 0.499 |

| Hydrocodone | 45 (9) | 48 (10) | 0.418 |

| Oxycodone | 55 (10) | 55 (12) | 0.590 |

| Codeine | 29 (6) | 16 (3) | 0.115 |

| Methadone | 4 (1) | 6 (1) | 0.447 |

| Fentanyl patch | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | - |

| Hydromorphone | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 0.651 |

| Morphine | 3 (1) | 1 (0) | 0.387 |

| Pain score, median (IQR) | |||

| Average NRS score | 3.3 (1.8–4.8) | 3.3 (1.8–4.7) | 0.740 |

| Average BPS score | 2.5 (2.1–3.0) | 2.3 (1.8–3.0) | 0.028 |

BPS, behavioral pain score; IQR, interquartile range; MME, morphine milligram equivalents; MMPR, multimodal pain regimen; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale

Patients randomized to the MAST MMPR also had a lower total MME (164 MME, IQR [59, 450] versus 218 MME, IQR [43, 490], p<0.001) (Table 3). Upon zero-inflated negative binomial modelling, the estimated marginal mean of the MAST MMPR was lower than that of the original MMPR (262 MME, 95% CrI 233-296 versus 274 MME, 95% CrI 246-307, posterior probability 0.77).

Conducting a priori analyses for subgroup differences, an interaction was found between treatment group and unit of admission for total MME (eTables 1 and 2). For patients admitted to the floor, IMU, or ICU, there were higher odds of having zero total MME in the MAST MMPR (Table 4). Despite that, patients admitted to the IMU and ICU had a 12% and 8% increase in total MME, respectively. Taken together, MAST MMPR patients had increased estimated marginal means of total MME when admitted to both the ICU and to the IMU. Alternatively, the MAST MMPR reduced the estimated marginal mean of total MME by 23% in patients admitted to the floor.

Table 4.

A Priori Subgroup Analysis of Total Morphine Milligram Equivalent and Opioid at Discharge by Unit of Admission

| Admission unit |

Total MME estimate mean and zero inflated negative binomial model | Opioid at discharge | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original MMPR, mean (95% CrI) |

MAST MMPR, mean (95% CrI) |

Zero-inflated component |

Negative binomial component |

Original MMPR, n (%) |

MAST MMPR, n (%) |

RR (95% CrI) |

Posterior probability* |

|||

| OR (95% CrI) |

Posterior probability* |

IRR (95% CrI) |

Posterior probability* |

|||||||

| Floor | 304 (266–348) | 232 (203–267) | 1.20 (0.02–73.88) | 0.57 | 0.77 (0.64–0.92) | 0.98 | 239 (77) | 207 (70) | 0.91 (0.88–1.18) | 0.97 |

| IMU | 285 (244–336) | 312 (265–371) | 19.93 (1.55–9,273.44) | 0.99 | 1.12 (0.89–1.41) | 0.17 | 134 (62) | 135 (64) | 1.02 (0.88–1.18) | 0.59 |

| ICU | 930 (804–1,082) | 1,004 (868–1,169) | 2.15 (0.03–601.05) | 0.71 | 1.08 (0.87–1.35) | 0.24 | 154 (59) | 134 (51) | 0.73 (0.86–1.00) | 0.97 |

The probability that the MAST MMPR reduced the outcome compared to the original MMPR.

CrI, credible interval; IRR, incidence risk ratio; IMU, intermediate unit; MME, morphine milligram equivalent; MMPR, multimodal pain regimen; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk.

The MAST MMPR had a lower rate of opioid prescribing at discharge than the original MMPR (62% versus 67%, p=0.029; RR 0.92, 95% credible interval 0.86-0.99, posterior probability RR<1 = 0.99) (Table 3). In both groups, tramadol was the most commonly prescribed opioid at discharge (89%), followed by oxycodone (11%), and hydrocodone (9%).

Similar to total MME, a priori subgroup analyses revealed an interaction between treatment group and unit of admission for the outcome opioid at discharge (Table 4). The MAST MMPR reduced opioid prescribing at discharge in patients admitted to the ICU and to the floor by 27% and 9%, respectively. The MAST MMPR had minimal effect on opioid prescribing at discharge on patients admitted to the IMU.

Pain Scales

Average NRS scores in the two treatment groups were similar for patients who could report pain scores (Table 3). eFigure 2 depicts the estimated marginal means for each group. A small increase in average daily NRS scores occurred in MMPR MAST (marginal mean difference 0.06, 95% credible interval −0.14–0.26; posterior probability 0.71). That is, the MAST MMPR increased the average daily NRS score by a trivial amount (0.06 on a scale of 0 to 10).

Among the nonverbal patients, the MAST MMPR had a lower average Behavioral Pain Scale score. The marginal means of each group are shown in eFigure 3. Posterior estimates suggest a small decrease in average daily BPS (marginal mean difference −0.08, 95% credible interval −0.14–0.02; posterior probability 0.99). After exponentiation this indicates an 8% reduction in average daily BPS for MMPR MAST relative to original MAST.

Other Secondary Outcomes

The two treatment groups were similar with respect to unplanned intubation, unplanned admission to the intensive care unit, cardiac arrest with resuscitation, ileus, or complications graded by ACDiT scores (eTable 3 and 4). Further, no differences were noted in the utilization of naloxone. There was no difference in hospital length of stay (estimate marginal mean of MAST MMPR 5.1 days, 95% CrI 4.7–5.6 versus original MMPR 5.0 days, 95% CrI 4.6–5.4, posterior probability 0.76).

DISCUSSION

In this large, pragmatic randomized trial of adult, injured patients, the use of the widely available MAST MMPR reduced inpatient opioid exposure and opioid prescribing at discharge with similar pain scores as compared to our original MMPR. This finding was contrary to our hypothesis.

Overall, the MAST trial demonstrates that an opioid-minimizing acute pain strategy is effective and feasible in such injured patients. We only enrolled patients admitted to the adult trauma service. Because a large proportion of patients with isolated extremity injuries were admitted to a medical service, the enrolled patients were a selectively more injured cohort. The median ISS of the entire cohort was 14 (IQR 9, 22) and 44% had an ISS >15 (definition of severe trauma).

Overall, the MAST MMPR not only reduced opioid exposure during hospitalization (MME/day and total MME) but also decreased opioid prescribing at discharge. In the MAST trial, 64% of patients were discharged with an opioid, of which only 25% received a schedule II drug such as oxycodone or hydrocodone. Seventy-five percent of patients discharged with an opioid prescription were discharged with tramadol only. In contrast, in a recent multi-center prospective observational study at seven trauma centers, 73% of patients were prescribed opioids at discharge; 86% of those patients (63% of all patients) received Schedule II drugs.(2) Similarly, Chaudhary and colleagues reported that 54% of trauma patients were discharged with a schedule II or III opioid prescription.(25) However they targeted a less severely injured population (median ISS 5, IQR [4, 10]) and did not count tramadol (schedule IV) as a discharge opioid. Thus, there is significant opportunity for MAST to inform hospital opioid prescribing practices.

While the generalizability of this strategy is likely to be high, more research is needed to responsibly and effectively address and understand the acute pain needs of our patients. The MAST trial has highlighted many gaps in the current understanding of MMPRs after injury.

First, while MME/day was reduced in all levels of care, the interpretation of the outcomes total MME and opioid prescribing at discharge was challenging as there was an interaction between treatment group and unit of admission for these outcomes. Given the lower MME/day, lower overall total MME, and lower opioid prescribing at discharge, the MAST MMPR was superior to the original MMPR in patients admitted to the floor. In patients admitted to the IMU, the MAST MMPR decreased MME/day and increased the odds of having zero total MME but increased total MME for patients likely to receive opioids and had minimal effect on opioid prescribing at discharge. For patients admitted to the ICU, the MAST MMPR decreased MME/day, increased the odds of having zero total MME, and decreased opioid prescribing at discharge, but increased the total MME for patients likely to receive opioids. In summary, the MAST MMPR appears more appealing for patients admitted to the floor and ICU. The results of patients admitted to the IMU appear neutral comparing the MAST and original MMPRs. Clinically, having one MMPR for a unit of admission (IMU) and another for the other two (ICU and floor) would complicate adherence to an acute pain protocol and our group intends to implement the MAST MMPR as our usual practice for all levels of care.

Second, conclusions cannot be made regarding the effectiveness of the individual components of the two MMPRs. More evidence is accumulating that acetaminophen and NSAIDs provide equivalent acute pain control as opioids.(26, 27) The evidence for gabapentin and lidocaine patches, however, remains mixed.(28-31) While lidocaine patches are innocuous and do not imbue a risk for long-term abuse, the abuse of gabapentin is being increasingly reported and the incremental effect of gabapentin in our current regimen is currently unknown.(32, 33) Future trials should evaluate the effectiveness of gabapentin in MMPRs. Other promising interventions described in the literature for reducing opioid exposure after injury and opioid prescribing after surgery were also not evaluated. These may include expectation-setting or non-pharmacologic interventions, such as virtual reality.(34) Strategies such as development and implementation of a protocol and/or guidelines,(35) use of order sets via the electronic health record,(36, 37) and education on opioid prescribing for trainees(38) were all performed in this trial, but for both groups. Thus, the relative effectiveness of each is unknown in this patient population.

Lastly, the measurement of acute pain longitudinally from arrival in the emergency department through multiple operations, critical illness, and during recovery continues to be exceedingly difficult. More objective measures of pain, such as sensory testing, are available but not feasible in such a large-scale and dynamic setting as trauma units. While we relied on the ubiquitous NRS and BPS collected in everyday patient care to help us identify any signal of undertreated acute pain in a standard fashion, feasible and scalable measurements of acute pain for clinical trials powered to change practice are needed. While the MAST MMPR had a lower average BPS score and no clinically significant difference in average NRS pain scores, we cannot state that acute pain control was better given the limitations estimating acute pain. At most, there was no evidence that acute pain was increased due to the MAST MMPR despite the overall lower opioid exposure.

This study’s limitations were linked to the pragmatic design needed to enroll a large number of patients in a relatively short trial under real world conditions. The majority of the data was collected electronically and adherence to the regimen was not was tracked. Reasons why the bedside physicians adjusted pain medications were not collected so we cannot speculate which, if any, individual classes of drugs confer the most benefit. However, this was beyond the scope or intent of this study. Also, this trial also was performed in a center with a history of adopting MMPRs. The original MMPR was adopted in 2013 and was, at first, resisted by many providers. To normalize the fact that acute pain due to trauma could be controlled with opioid-minimizing MMPRs took many years. This trial was performed in a trauma center where the culture of treating acute pain in an opioid-minimizing manner was established. Implementing the MAST MMPR in centers without such an established background could either limit or increase the MMPR’s effectiveness. Lastly, while total MME provided better model fit compared to MME/day, opioid prescribing at discharge is more compelling as a surrogate for persistent opioid use. Future studies should consider opioid prescribing at discharge as the primary outcome.

Conclusion

The MAST MMPR reduced opioid exposure and discharge from the hospital with an opioid prescription while achieving similar pain control after trauma. These findings underscore the efficacy of opioid-minimizing strategies after trauma and the MAST MMPR has become usual practice for injured patients admitted to our trauma center.

Supplementary Material

eFigure 1: Estimated total morphine milligram equivalents (MME) as a function of group. MAST, Multimodal Analgesic Strategies in Trauma; MMPR, multimodal pain regimen.

eFigure 2: Estimated average daily numeric rating scale (NRS) pain score as a function of group. MAST, Multimodal Analgesic Strategies in Trauma; MMPR, multimodal pain regimen.

eFigure 3: Estimated average daily behavioral pain scale (BPS) as a function of group. MAST, Multimodal Analgesic Strategies in Trauma; MMPR, multimodal pain regimen.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the residents and fellows of the Red Duke Trauma Center at Memorial Hermann Hospital-Texas Medical Center and the McGovern Medical School at UT Health for their active participation in and support of this trial. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Peter V. Killoran for his assistance obtained electronic data and Michelle Sauer, PhD, ELS for her editorial contributions.

Support: Dr Harvin was supported by the Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences, which is funded by NIH Clinical and Translational Award UL1 TR000371 and KL2 TR000370 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Appendix

Members of the Multimodal Analgesic Strategies for Trauma (MAST) Study Group: Jessica A Hudson, MD, Department of Surgery; Ethan A Taub, DO, David E Meyer, MD, Sasha D Adams, MD, FACS, Laura J Moore, MD, FACS, Michelle K McNutt, MD, FACS, Center for Translational Injury Research and the Department of Surgery, McGovern Medical School, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas; John B Holcomb, MD, FACS, Center for Injury Science, Department of Surgery, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Footnotes

Members of the MAST Study Group who co-authored this article are listed in the Appendix.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov [NCT03472469]

Disclosure Information: Dr Albarado receives speaker payments from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals Speakers Bureau (Ofirmev).

Disclosures outside the scope of this work: Dr Holcomb is a paid consultant to PotentiaMetrics, Inc; Arsenal Medical, Inc; Cellphire, Inc; and CSL Limited; is a paid advisor to Spectrum Medical and Safeguard Medical, LLC; receives equity as a member of the Board of Directors for Decisio Health, QinFlow, and ZIBRIO; and receives royalty payments from UT Health as co-inventor of the Junctional Emergency Tourniquet Tool. Other authors have nothing to disclose.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the NIH. This trial was also supported by a Learning Healthcare Award from the McGovern Medical School at University of Texas Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.von Oelreich E, Eriksson M, Brattstrom O, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of chronic opioid use following trauma. Br J Surg. March 2020;107(4):413–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvin JA, Truong VTT, Green CE, et al. Opioid exposure after injury in United States trauma centers: A prospective, multicenter observational study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. June 2020;88(6):816–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wick EC, Grant MC, Wu CL. Postoperative Multimodal Analgesia Pain Management With Nonopioid Analgesics and Techniques: A Review. JAMA Surg. July 2017;152(7):691–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitchon DN, Dayan AC, Schwenk ES, et al. Updates on Multimodal Analgesia for Orthopedic Surgery. Anesthesiol Clin. September 2018;36(3):361–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sim V, Hawkins S, Gave AA, et al. How low can you go: Achieving postoperative outpatient pain control without opioids. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. July 2019;87(1):100–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rafiq S, Steinbrüchel DA, Wanscher MJ, et al. Multimodal analgesia versus traditional opiate based analgesia after cardiac surgery, a randomized controlled trial. J Cardiothoracic Surg. March 2014;9:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reagan KML, O'Sullivan DM, Gannon R, Steinberg AC. Decreasing postoperative narcotics in reconstructive pelvic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. September 2017;217(3):325.e1–e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei S, Green C, Thanh Truong VT, et al. Implementation of a multi-modal pain regimen to decrease inpatient opioid exposure after injury. Am J Surg. December 2019;218(6):1122–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvin JA, Green CE, Vincent LE, et al. Multi-modal Analgesic Strategies for Trauma (MAST): protocol for a pragmatic randomized trial. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. August 2018;3(1):e000192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naumann DN, Vincent LE, Pearson N, et al. An adapted Clavien-Dindo scoring system in trauma as a clinically meaningful nonmortality endpoint. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. August 2017;83(2):241–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Trauma Data Bank ACoS. National Trauma Data Standard Dictionary; 2018. Admissions. Available at: facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/tqp/center-programs/ntdb/ntds. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- 12.National Trauma Data Bank ACoS. National Trauma Data Standard Dictionary; 2019. Admissions. Available at: https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/tqp/center-programs/ntdb/ntds. Accessed February 19, 2020.

- 13.Spiegelhalter DJ, Abrams KR & Myles JP Bayesian Approaches to Clinical Trials and Health-Care Evaluation. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quintana M, Viele K, Lewis RJ. Bayesian Analysis: Using Prior Information to Interpret the Results of Clinical Trials. JAMA. October 2017;318(16):1605–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wijeysundera DN, Austin PC, Hux JE, et al. Bayesian statistical inference enhances the interpretation of contemporary randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. January 2009;62(1):13–21 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis RJ, Angus DC. Time for Clinicians to Embrace Their Inner Bayesian?: Reanalysis of Results of a Clinical Trial of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. JAMA. December 2018;320(21):2208–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amrhein V, Greenland S, McShane B. Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature. March 2019;567(7748):305–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA Statement on p-Values: Context, Process, and Purpose. The American Statistician. 70(2):129–33. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodges JL, Lehmann EL. Rank Methods for Combination of Independent Experiments in Analysis of Variance. In: Rojo J, ed. Selected Works of E L Lehmann. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2012. p. 403–18. [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaVange LM, Koch GG. Rank score tests. Circulation. December 2006;114(23):2528–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehrotra DV, Lu X, Li X. Rank-Based Analyses of Stratified Experiments: Alternatives to the van Elteren Test. The American Statistician. 64(2):121–30. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Team. SD. RStan: the R interface to Stan: Stan Development Team. Available from: http://mc-stan.org . 2017.

- 23.R. The R Project. http://www.r-project.org/.

- 24.SAS I. SAS v 9.4.

- 25.Chaudhary MA, Schoenfeld AJ, Harlow AF, et al. Incidence and Predictors of Opioid Prescription at Discharge After Traumatic Injury. JAMA Surg. October 2017;152(10):930–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, et al. Effect of a Single Dose of Oral Opioid and Nonopioid Analgesics on Acute Extremity Pain in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. November 2017;318(17):1661–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thybo KH, Hagi-Pedersen D, Dahl JB, et al. Effect of Combination of Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) and Ibuprofen vs Either Alone on Patient-Controlled Morphine Consumption in the First 24 Hours After Total Hip Arthroplasty: The PANSAID Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. February 2019;321(6):562–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng YJ. Lidocaine Skin Patch (Lidopat(R) 5%) Is Effective in the Treatment of Traumatic Rib Fractures: A Prospective Double-Blinded and Vehicle-Controlled Study. Med Princ Pract. 2016;25(1):36–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ingalls NK, Horton ZA, Bettendorf M, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial using lidocaine patch 5% in traumatic rib fractures. J Am Coll Surg. February 2010;210(2):205–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moskowitz EE, Garabedian L, Hardin K, et al. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial of gabapentin vs. placebo for acute pain management in critically ill patients with rib fractures. Injury. September 2018;49(9):1693–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hah J, Mackey SC, Schmidt P, et al. Effect of Perioperative Gabapentin on Postoperative Pain Resolution and Opioid Cessation in a Mixed Surgical Cohort: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. April 2018;153(4):303–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evoy KE, Morrison MD, Saklad SR. Abuse and Misuse of Pregabalin and Gabapentin. Drugs. March 2017;77(4):403–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johansen ME. Gabapentinoid Use in the United States 2002 Through 2015. JAMA Intern Med. February 2018;178(2):292–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mallari B, Spaeth EK, Goh H, Boyd BS. Virtual reality as an analgesic for acute and chronic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Res. July 2019;12:2053–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Earp BE, Silver JA, Mora AN, Blazar PE. Implementing a Postoperative Opioid-Prescribing Protocol Significantly Reduces the Total Morphine Milligram Equivalents Prescribed. J Bone Joint Surg Am. October 2018;100(19):1698–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baird J, Faul M, Green TC, et al. Evaluation of a Safer Opioid Prescribing Protocol (SOPP) for Patients Being Discharged From a Trauma Service. J Trauma Nurs. May-Jun 2019;26(3):113–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luk LJ, Mosen D, MacArthur CJ, Grosz AH. Implementation of a Pediatric Posttonsillectomy Pain Protocol in a Large Group Practice. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. April 2016. Apr;154(4):720–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiu AS, Ahle SL, Freedman-Weiss MR, et al. The impact of a curriculum on postoperative opioid prescribing for novice surgical trainees. Ame J Surg. February 2019;217(2):228–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1: Estimated total morphine milligram equivalents (MME) as a function of group. MAST, Multimodal Analgesic Strategies in Trauma; MMPR, multimodal pain regimen.

eFigure 2: Estimated average daily numeric rating scale (NRS) pain score as a function of group. MAST, Multimodal Analgesic Strategies in Trauma; MMPR, multimodal pain regimen.

eFigure 3: Estimated average daily behavioral pain scale (BPS) as a function of group. MAST, Multimodal Analgesic Strategies in Trauma; MMPR, multimodal pain regimen.