Abstract

Objective

This study aimed at developing a quantitative approach to assess abnormalities on MRI of the brachial plexus and the cervical roots in patients with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) and multifocal motor neuropathy (MMN) and to evaluate interrater reliability and its diagnostic value.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional study in 50 patients with CIDP, 31 with MMN and 42 disease controls. We systematically measured cervical nerve root sizes on MRI bilaterally (C5, C6, C7) in the coronal [diameter (mm)] and sagittal planes [area (mm2)], next to the ganglion (G0) and 1 cm distal from the ganglion (G1). We determined their diagnostic value using a multivariate binary logistic model and ROC analysis. In addition, we evaluated intra- and interrater reliability.

Results

Nerve root size was larger in patients with CIDP and MMN compared to controls at all predetermined anatomical sites. We found that nerve root diameters in the coronal plane had optimal reliability (intrarater ICC 0.55–0.87; interrater ICC 0.65–0.90). AUC was 0.78 (95% CI 0.69–0.87) for measurements at G0 and 0.81 (95% CI 0.72–0.91) for measurements at G1. Importantly, our quantitative assessment of brachial plexus MRI identified an additional 10% of patients that showed response to treatment, but were missed by nerve conduction (NCS) and nerve ultrasound studies.

Conclusion

Our study showed that a quantitative assessment of brachial plexus MRI is reliable. MRI can serve as an important additional diagnostic tool to identify treatment-responsive patients, complementary to NCS and nerve ultrasound.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00415-020-10232-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging, Brachial plexus, Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, Multifocal motor neuropathy, Diagnostic value

Introduction

Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) and multifocal motor neuropathy (MMN) are rare disorders that often respond to treatment. Diagnostic criteria have been developed to distinguish CIDP and MMN from more common neuropathies and motor neuron disorders that rely on sets of typical clinical combined with specific electrodiagnostic features [1, 2]. Diagnosing CIDP or MMN remains challenging when nerve conduction studies (NCS) do not meet the required electrodiagnostic criteria [2, 3].

Nerve imaging by means of qualitative MRI is recommended in diagnostic guidelines for cases without NCS abnormalities. MRI of the brachial plexus and cervical nerve roots shows nerve root thickening and increased T2 signal intensity in 45–57% of patients [4–7]. These abnormalities have therefore been included as a supportive criterium in the diagnostic criteria for CIDP and MMN [1, 2]. However, qualitative assessments showed low interrater reliability [8, 9]. In contrast, a quantitative assessment of nerve ultrasound showed excellent test characteristics for the detection of inflammatory neuropathies [10–13]. This suggests that quantification of MRI abnormalities may improve its diagnostic value.

Therefore, the aim of our study was to systematically assess nerve root sizes on MRI of the brachial plexus and cervical nerve roots in a large cohort of patients with chronic inflammatory neuropathies and relevant disease controls. Using these data, we investigated interrater reliability and the diagnostic value of MRI in addition to NCS and nerve ultrasound.

Methods

Study design

We performed a cross-sectional study in prevalent and incident patients with CIDP and MMN, and clinically relevant controls [i.e. amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or progressive muscular atrophy (PMA)]. We used a standardized protocol to systematically assess cervical nerve root sizes, determined their diagnostic value and reproducibility and developed a risk chart including objective cut-off values for abnormality.

Patients and clinical data

All prevalent and incident patients with an established diagnosis of CIDP or MMN, visiting our neuromuscular outpatient clinic at the University Medical Center Utrecht (UMCU), were eligible for inclusion. We used previously published diagnostic criteria for CIDP and MMN, in short for CIDP we used the diagnostic criteria as defined in the EFNS/PNS guideline and for MMN we used the Utrecht criteria [1, 2]. As disease controls, we enrolled a random sample of patients with motor neuron disease (ALS and PMA), according to the Brooks criteria [14]. We excluded patients aged < 18 years, patients with motor neuron disease that had a bulbar onset of symptoms and patients who were physically unable to undergo MRI or who met one of the routine contraindications to MRI (e.g. pacemaker, non-MRI approved surgical clips or implants, claustrophobia, a recent prosthetic operation).

We obtained demographic and clinical data, including treatment response and results from routine diagnostic work-up, i.e. diagnostic NCS and nerve ultrasound results. Treatment response was evaluated based on the discretion of the treating physician. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Routine diagnostic work-up

Nerve conduction studies

Diagnostic NCS were performed using a Nicolet Viking IV EMG machine (CareFusion Japan, Tokyo, Japan) following previously described protocols [10, 15]. The results were interpreted using the EFNS/PNS criteria for CIDP (definite, probable, possible) and the Utrecht criteria for MMN (definite motor conduction block, probable motor conduction block, slowing of conduction compatible with demyelination) [1, 2].

Nerve ultrasound

Diagnostic nerve ultrasound was performed using a Philips Affinity 70G (Philips Medical Instruments, eL 1–48 MHz linear array transducer) following a previously published protocol [10]. In short, we collected nerve sizes of the median nerves (forearm and upper arm) and brachial plexus trunks bilaterally. We used the ellipse tool to measure cross sectional area (mm2) and we used cut-off values for abnormal nerve size to identify patients with a chronic inflammatory neuropathy (median nerve forearm > 10 mm2 and upper arm > 13 mm2; plexus trunks > 9 mm2). Nerve ultrasound was considered abnormal if nerve enlargement was present at ≥ 1 measured sites.

Equipment and MRI parameters

All patients underwent an MRI scan of the brachial plexus and cervical nerve roots on a 3.0 T MRI scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) using a 24-channel head neck coil. All participants were positioned in supine position. We performed 3D turbo spin echo spectral presaturation with inversion recovery (SPIR) in a coronal and sagittal slice orientation with the following acquisition parameters: field of view = 336 × 336 × 170 mm, matrix size = 224 × 223, voxel size = 0.75 × 0.75 × 1 mm3, echo time = 206 ms, repetition time = 2200 ms, turbo spin echo factor = 76, sense factor = 3 (P reduction right/left) and 1.5 (S reduction anterior/posterior), acquisition time = 03:59 min. A coronal slab maximum intensity projection (MIP) was created as a post-processing step (slab thickness = 10 mm, number of slabs = 75).

Nerve root measurements on MRI data

We measured cervical nerve root sizes in coronal and sagittal planes, using PACS IDS7 21.1.2 (Sectra AB, Linköping, Sweden). We used the distance tool to measure diameters (mm) of nerve roots in coronal MIP images. Nerve root diameter was measured perpendicular on the center lines of the nerve roots, bilaterally in root C5, C6 and C7 at two predetermined anatomical sites: directly next to the ganglion (G0) and 1 cm distal from the ganglion (G1). In addition, we used the cross-cursor tool to identify the corresponding sites of these measurements on the sagittal 3D TSE SPIR, and measured cross sectional area (mm2) in the sagittal plane using the area tool, which is a manual tracer, resulting in 24 measurements in total per subject (duration 3–5 min per subject, Fig. 1). Zoom magnification was standardized to 1 × for all images. As anatomic variability in the brachial plexus is common and may be even more present in more distal parts [16], we decided to not perform measurements when individual nerve roots merged, divided or showed other anatomical variances. We also did not perform measurements when image quality was poor. To determine intrarater reliability, one rater (MVR) performed all measurements twice in two sessions with an interval of 1 month between the first and second sessions. To determine interrater reliability a second rater (AG) scored a random sample of 20 MRI scans from our data set. Both raters were blinded to clinical status.

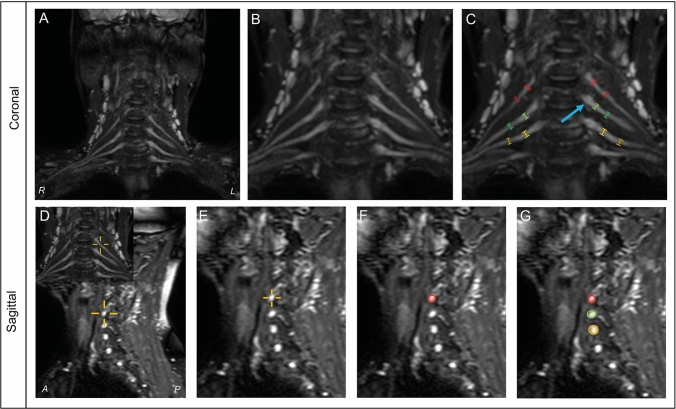

Fig. 1.

Example of nerve root measurements in coronal and sagittal planes. Method of measurements in coronal (upper) and sagittal (lower) planes. Coronal measurements in maximum intensity projection images (a) using 1 × zoom (b) and calipers placed in nerve root C5 (red), C6 (green) and C7 (yellow) next to the ganglion (blue arrow) and 1 cm distal of the ganglion (c). Sagittal measurements in T2 weighted fat-suppressed images using a cross-cursor to identify corresponding measurement sites (d) and 1 × zoom (e). Measurements were then performed at these corresponding measurement sites (f, g). R right; L left; A anterior; P posterior

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 25, Chicago, Illinois, United States) was used for statistical analysis. To compare patient characteristics between cases and controls, we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for numerical data and χ2 test for categorical data. To evaluate the feasibility of our method, we compared numbers of successfully performed measurements between the coronal and sagittal plane and between G0 and G1 using an independent samples t test. To determine mean nerve root size we also used an independent samples t test. Results with a p value < 0.05 were considered significant. To evaluate intra- and interrater reliability we used the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). We calculated a mean ICC of the right and left sides per measurement site. We considered an ICC < 0.50 as poor reliability, 0.50–0.75 as moderate, 0.75–0.90 as good and > 0.90 as excellent reliability [17].

ROC analysis and development of risk chart

We used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to determine area under the curve (AUC) per nerve root (C5, C6, C7) and for two different combinations of measurement: (1) mean of all three nerve roots bilaterally next to the ganglion (3 variables) and (2) mean of all three nerve roots 1 cm distal from the ganglion (3 variables). We then used a multivariate binary logistic model for both combinations separately with measurement sites as covariates. With the results of this model we calculated the log odds for having an inflammatory neuropathy using the following equation (Eq. 1):

| 1, |

where 0 is the constant, β1, β2 and β3 the logistic regression coefficients of nerve roots C5, C6 and C7 respectively and C5, C6 and C7 the diameters of the nerve roots in millimetres. Subsequently, we took the inverse logit to obtain , i.e. the absolute probability of having an inflammatory neuropathy, using the following equation (Eq. 2):

| 2 |

To develop a risk chart, we calculated for different combinations of C5, C6 and C7 and for both combinations of measurement sites. Finally, we obtained a cut-off value for obtaining 95% specificity, i.e. we determined at which we considered MRI to be abnormal.

Results

Patients

We included a total of 123 patients (CIDP = 50, MMN = 31, disease controls = 42). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients with MMN were younger than patients with CIDP and disease controls (p < 0.001). We found no significant differences in other baseline characteristics between groups.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Parameter | Inflammatory neuropathy | Motor neuron disease | Level of significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIDP | MMN | |||

| Number of patients | 50 | 31 | 42 | – |

| Age, years (SD) | 63.8 (9.4) | 52.5 (11.7) | 63.1 (11.2) | < 0.001* |

| Male (%) | 42 (84.0%) | 29 (93.5%) | 31 (73.8%) | 0.083 |

| Disease duration, months (SD) | 33.6 (65.2) | 61.8 (80.5) | 45.4 (38.1) | 0.143 |

| Nerve conduction study | ||||

| Inconclusive (%) | 14 (28.0%) | 7 (22.6%) | – | |

| Possible (CIDP)/slowing of conduction (MMN) (%) | 9 (18.0%) | 3 (9.7%) | – | |

| Probable (%) | 2 (4.0%) | 3 (9.7%) | – | |

| Definite (%) | 25 (50.0%) | 18 (58.1%) | – | |

| Ultrasound | ||||

| Normal (%) | 10 (20.0%) | 6 (19.4%) | 5 (11.9%) | |

| Abnormal (%) | 35 (70.0%) | 25 (80.6%) | 3 (7.1%) | |

| Missing (%) | 5 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 34 (81.0%) | |

*Age differs significantly between patients with MMN and patients with CIDP, and between patients with MMN and disease controls

Nerve root measurements on MRI

Feasibility of measuring method

Supplemental Table 1 summarizes the number of measurements per nerve root that could be performed successfully. We obtained more measurements at G0 compared to G1 (p < 0.001). Measurements in the coronal plane were more often successful than in the sagittal plane (p < 0.001). We established that this was mostly related to early merging or dividing nerve roots and the fact that images showed lower image quality more distally.

Intra- and interrater reliability

Table 2 shows the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) within and between raters. We found moderate to good intrarater reliability in both plane orientations (ICC 0.55–0.87 in coronal plane, and 0.63–0.86 in sagittal plane). We found moderate to good interrater reliability in the coronal plane (ICC 0.65–0.90) but a poor to good reliability in the sagittal plane (ICC 0.47–0.84). Overall, we found higher consistency in measurements performed in the coronal plane orientation.

Table 2.

Reliability of nerve root measurements on brachial plexus MRI

| Site | Intrarater reliability | Interrater reliability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronal | Sagittal | Coronal | Sagittal | |

| C5 | ||||

| Ganglion | 0.81 (0.74–0.86) | 0.69 (0.58–0.77) | 0.81 (0.58–0.92) | 0.52 (0.09–0.78) |

| 1 cm | 0.55 (0.41–0.67) | 0.63 (0.47–0.74) | 0.78 (0.51–0.91) | 0.62 (0.14–0.87) |

| C6 | ||||

| Ganglion | 0.77 (0.69–0.84) | 0.68 (0.58–0.77) | 0.77 (0.37–0.89) | 0.47 (0.04–0.75) |

| 1 cm | 0.84 (0.77–0.89) | 0.83 (0.74–0.88) | 0.82 (0.58–0.93) | 0.79 (0.50–0.92) |

| C7 | ||||

| Ganglion | 0.78 (0.70–0.84) | 0.75 (0.67–0.82) | 0.65 (0.13–0.87) | 0.73 (0.44–0.89) |

| 1 cm | 0.87 (0.81–0.91) | 0.86 (0.79–0.91) | 0.90 (0.60–0.97) | 0.84 (0.35–0.96) |

Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with 95% confidence interval for every measurement site in coronal and sagittal planes

Mean nerve root size

Mean nerve root sizes are summarized in Table 3. Nerve root sizes in patients with CIDP and MMN were larger compared to disease controls, at all predetermined anatomical sites (p varied from < 0.001 to 0.026).

Table 3.

Mean nerve root sizes per measurement site

| Nerve root | Inflammatory neuropathy (n = 81) | Control (n = 42) | MD (95% CI) | Level of significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronal | ||||

| C5 | ||||

| Ganglion (SD) | 3.0 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | < 0.001 |

| 1 cm (SD) | 2.8 (0.9) | 2.2 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.3–0.8) | < 0.001 |

| C6 | ||||

| Ganglion (SD) | 3.8 (0.9) | 3.3 (0.6) | 0.5 (0.2–0.8) | < 0.001 |

| 1 cm (SD) | 3.6 (1.1) | 2.9 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.3–1.1) | < 0.001 |

| C7 | ||||

| Ganglion (SD) | 4.0 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.3–1.0) | < 0.001 |

| 1 cm (SD) | 3.7 (1.1) | 2.8 (0.6) | 0.9 (0.4–1.4) | < 0.001 |

| Sagittal | ||||

| C5 | ||||

| Ganglion (SD) | 21.6 (6.8) | 18.5 (5.7) | 3.1 (0.7–5.6) | 0.013 |

| 1 cm (SD) | 20.3 (7.2) | 16.7 (4.4) | 3.6 (1.1–6.1) | 0.005 |

| C6 | ||||

| Ganglion (SD) | 27.2 (9.1) | 23.4 (5.2) | 3.8 (0.8–6.8) | 0.013 |

| 1 cm (SD) | 25.3 (11.5) | 19.2 (6.5) | 6.1 (2.0–10.2) | 0.004 |

| C7 | ||||

| Ganglion (SD) | 26.4 (10.4) | 22.0 (5.4) | 4.4 (1.5–7.2) | 0.003 |

| 1 cm (SD) | 23.1 (14.7) | 16.1 (4.3) | 7.1 (0.9–13.3) | 0.026 |

Nerve root sizes are mean. Coronal measurements are in millimetres (mm). Sagittal measurements are square millimetres (mm2)

MD mean difference, CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation

ROC analysis and development of risk chart

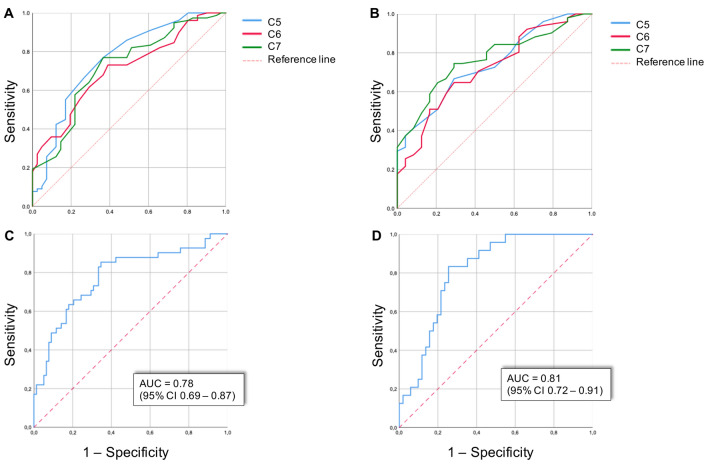

Sagittal measurements were less often successful because of lower data quality and overall lower reliability (Table 2 and supplemental Table 1). We therefore decided to exclude the measurements in the sagittal plane from further analysis. Results from the ROC analysis are shown in Fig. 2. We found a comparable AUC for both predetermined anatomical sites in the coronal plane (G0 and G1). We developed a risk chart (Fig. 3) that predicts the absolute chance of having a chronic inflammatory neuropathy, based on different combinations of nerve root sizes of C5, C6 and C7.

Fig. 2.

ROC analysis of nerve root size measurements on MRI. ROC curves of measurements per nerve root next to the ganglion (a) and 1 cm distal of the ganglion (b) are shown in the upper panels. Combined ROC curves of measurements next to the ganglion (c) and 1 cm distal of the ganglion (d) are shown in the lower panels. Combined measurements are expressed as area under the curve (AUC) and 95% confidence interval (CI)

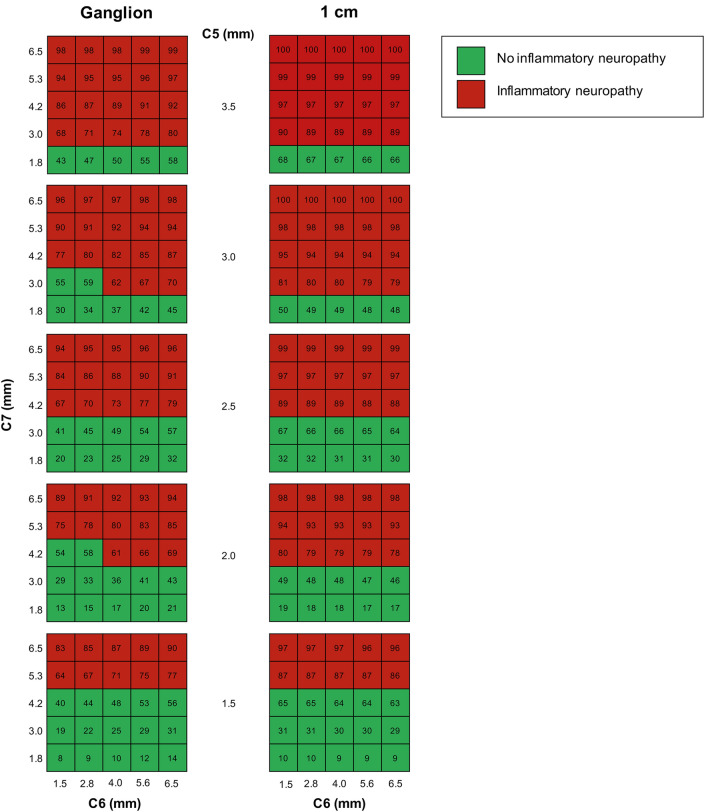

Fig. 3.

Risk chart for predicting CIDP or MMN based on nerve root sizes. Risk charts for measurements next to the ganglion (left panels) and 1 cm distal from the ganglion (right panels). The risk chart provides the absolute risk of having CIDP or MMN based on different combinations of nerve root thickness of nerve root C5, C6 and C7. Every cell of the table contains the probability of having CIDP or MMN (e.g. for measurements next to the ganglion (left panels): if C5 is 1.5 mm, C6 is 1.5 mm and C7 is 1.8 mm, the probability of having CIDP or MMN is 8%). A probability of ≥ 61% for measurements next to the ganglion and ≥ 69% for measurements 1 cm distal from the ganglion were considered abnormal (cells in red). The axes range between the 95% lowest and highest measurements

The added value of MRI

ROC analysis showed that at a set specificity of 95%, the sensitivities are 27% for G0 and 17% at G1. With this specificity, a probability of ≥ 61% for measurements at G0 and ≥ 69% at G1 in the risk chart were considered abnormal or likely to have a chronic inflammatory neuropathy (Fig. 3). With these cut-off values, we determined which patients in our data set had an abnormal MRI and we investigated the added value of brachial plexus MRI in addition to NCS and nerve ultrasound. We found that NCS combined with nerve ultrasound identified most patients with an inflammatory neuropathy. The majority of patients with abnormal ultrasound findings also had abnormal MRI findings (Fig. 4). However, 5/50 (10%) patients with CIDP had an abnormal MRI result, while NCS did not fullfill the criteria for CIDP and ultrasound did not show abnormalities. All patients had a good response to treatment. Clinical symptoms and laboratory findings of these five patients are summarized in Table 4. MRI did not have any added diagnostic value for MMN.

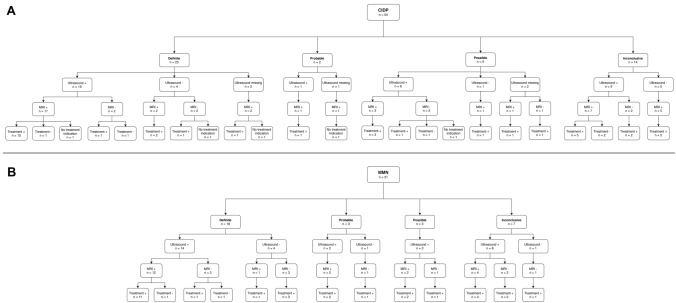

Fig. 4.

Results of NCS, ultrasound and MRI in patients with CIDP and MMN. Flow chart of CIDP patients (a) and MMN patients (b) showing outcome of nerve conduction studies, nerve ultrasound of the brachial plexus and median nerve, MRI of the brachial plexus and cervical nerve roots and treatment response

Table 4.

Patient characteristics of patients with CIDP who did not fulfil diagnostics criteria on NCS and without ultrasound abnormalities

| Patient | Male/female | Clinical presentation | NCS | Electrodiagnostic criteria* | Liquor protein in g/L (normal 0.00–0.40) |

Treatment and dosage | Response to treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | Symmetrical weakness in proximal and distal arm and leg muscles; loss of vibration, touch and position sense in arms and legs; areflexia | CMAP↓ right median, right peroneal and left tibial nerve. ↑DML bilateral median nerves. ↓SNAP bilateral median, ulnar, radial and sural nerves | Not compatible | 0.39 | Intravenous immunoglobulins, 40 g every 3 weeks | Improvement of pinch force right hand from 55 to 100 kPa, improvement pinch force left hand of 30 kPa to 98 kPa, measured with Martin vigorimeter |

| 2 | Male | Asymmetrical weakness in proximal and distal right arm muscles and right leg muscles; loss of vibration sense distal from knees; low reflexes in the arms, areflexia in the legs | CMAP↓ bilateral median, right ulnar, bilateral peroneal and left tibial nerve. ↑DML bilateral median nerves. Normal SNAP’s | Not compatible | 0.48 | Intravenous immunoglobulins, 30 g every 3 weeks | Improvement of dorsal flexion of right foot, measured with myometry by physiotherapist |

| 3 | Male | Asymmetrical weakness in proximal and distal right arm; tremor; loss of vibration sense in feet; areflexia | CMAP↓ right median nerve. ↑DML left median nerve. ↓SNAP bilateral median and sural nerves | Not compatible | 0.61 | Intravenous immunoglobulins, 40 g every 4 weeks | Improvement of MRC 4 to 5 in right arm, measured by treating physician |

| 4 | Male | Symmetrical weakness in proximal and distal leg muscles; fluctuating pain in legs; loss of vibration sense in feet; areflexia | CMAP↓ right peroneal and left tibial nerve. ↑DML right median and left ulnar nerve. ↓SNAP bilateral sural nerves | Not compatible | 0.70 | Methylprednisolone 1000 mg every 4 weeks | Improvement of MRC 3 to 4 (right) and MRC 4 to 5 (left) in quadriceps muscles, improvement of MRC 0 to 4 in left anterior tibial muscle, measured by treating physician. For 3 years ago in wheel chair, currently walks an hour (with walking stick) |

| 5 | Male | Symmetrical weakness in extensor hallucis longus muscle; loss of vibration and touch sense in feet up to the knees; low reflexes in the arms, areflexia in the legs | CMAP↓ left median, bilateral ulnar and peroneal, right tibial nerve. ↑DML right median nerve. ↓SNAP bilateral median, right ulnar, left tibial, bilateral sural | Not compatible | 0.42 | Single therapy of intravenous immunoglobulins, 40 g during 5 days | Improvement of touch sense (currently only persistent in feet), better balance, observed by treating physician |

Discussion

Quantitative assessment of brachial plexus MRI has acceptable interrater reliability and can be used in the diagnostic workup of patients who may have an inflammatory neuropathy. It can complement NCS and nerve ultrasound for the diagnosis of CIDP, but not MMN. A quantitative assessment of MRI of the brachial plexus and cervical nerve roots with high specificity identified 10% additional patients who responded to treatment but had not been identified by NCS and nerve ultrasound.

MRI is part of the current diagnostic criteria for CIDP and MMN and is recommended in particular for the identification of elusive cases, i.e. those without clear NCS abnormalities [1, 2, 18–21]. This is based on several MRI studies that showed cervical nerve root thickening and increased signal intensity on brachial plexus MRI in a subgroup of patients with chronic inflammatory neuropathies [7, 20]. A clear limitation of qualitative assessment of brachial plexus MRI as it is used nowadays is its low interrater reliability [8, 9]. Few studies have explored the feasibility and use of a quantitative MRI assessment and only in small groups of patients and healthy controls [9, 22–25]. Estimates of the upper limit of normal for cervical nerve root size in healthy controls ranged between 4 and 5 mm. Analysis of our data from a large cohort of patients with CIDP and MMN showed that combinations of nerve root size are probably more useful than a fixed cut-off. This may be explained by the patchy nature of inflammatory changes. We found that six bilateral measurements close to the ganglion of root C5, C6 and C7 in coronal plane was easy to implement in routine practice (~ 3 min per subject) and resulted in optimal test characteristics with high specificity levels. Sensitivity levels of quantitative assessment of brachial plexus MRI were lower than those reported in qualitative studies [23, 24]. This may be explained by some inclusion bias in earlier studies, as shown by another recent prospective cohort study that also reported a relatively low sensitivity of qualitative brachial and lumbosacral plexus MRI in patients with suspected CIDP [21]. Importantly, test–retest reliability for quantitative measurements was good, which is supported by data from another recent study [23].

We analyzed the diagnostic value of a quantitative assessment of MRI next to NCS and nerve ultrasound studies [10, 12, 13]. MRI helped to identify patients with a clinical phenotype compatible with CIDP but who did not fulfil the diagnostic criteria of NCS and who did not have ultrasound abnormalities. In this sense, MRI complements nerve ultrasound, which has an excellent sensitivity as shown in previous studies [10, 13]. Quantitative assessment of brachial plexus MRI identified an additional 10% of patients who responded to treatment, which is clinically relevant. MRI should, therefore, be considered as an additional diagnostic tool when there is a strong clinical suspicion of CIDP, particularly when NCS and nerve ultrasound results are normal. Nerve ultrasound, and especially the required expertise, is not always available in all medical centres. In these centres MRI could be used as an additional tool to NCS and laboratory findings, although physicians should always consider the poor sensitivity of MRI when interpreting results.

Our study comprises a relatively large number of patients with MMN and CIDP, although we acknowledge that the group sizes in studies on rare neuropathies are almost always a limitation. Our control group was homogeneous and did not include a spectrum of mimics as in previous studies. This was a deliberate choice since ultrasound studies showed that it is unlikely that nerve root sizes are enlarged in patients with axonal neuropathies [10]. We also acknowledge that both nerve imaging and NCS may fail to discriminate CIDP from certain rare mimics, such as hereditary demyelinating polyneuropathies, paraproteinaemic polyneuropathies and amyloidosis. However, clinical phenotypes and laboratory findings in these rare mimics will often guide a clinician to the right diagnosis without the use of nerve imaging techniques.

We show that quantitative assessment of MRI of the brachial plexus and cervical nerve roots is a reliable and useful tool for the diagnostic workup of patients who may have a chronic inflammatory neuropathy. A quantitative approach is feasible and does not have the limitation of high interrater variability of the currently used qualitative assessments.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank C.A.T. van den Berg and F. Visser for their support in MRI sequence development.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by MHJR, AG, RPAE, FA, SM and MF. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MHJR and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study is funded by the Prinses Beatrix Spierfonds (W.OR17-21).

Availability of data material

The data that support the findings of this study will be available on request from the corresponding author.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

M.H.J. van Rosmalen, A. van der Gijp, T.D. Witkamp, R.P.A. van Eijk, F. Asselman, S. Mandija and M. Froeling report no competing interests. H.S. Goedee has received research support from the Prinses Beatrix Spierfonds, speaker fee and travel grands from Shire/Takeda. L.H. van den Berg serves on scientific advisory boards for Orion, Orphazyme and Biogen; received an educational grant from Takeda; serves on the editorial board of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry; and receives research support from the Prinses Beatrix Spierfonds, Netherlands ALS Foundation, The European Community's Health Seventh Framework Programme (Grant agreement no. 259867), The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (Vici Scheme, JPND (SOPHIA, STRENGTH)). J. Hendrikse has received research support from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) under Grant no. 91712322 and the European Research Council under Grant agreements no. 637024. W.L. van der Pol has received support from the Prinses Beatrix Spierfonds and Stichting Spieren voor Spieren.

Ethical approval

The medical ethical committee of the UMCU approved this study (18-349/NL 62866.041.17) and this study have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

References

- 1.van den Bergh PYK, Hadden RDM, Bouche P, et al. European Federation of Neurological Societies/Peripheral Nerve Society Guideline on management of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: Report of a joint task force of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Peripher. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:356–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vlam L, Van Der Pol WL, Cats EA, et al. Multifocal motor neuropathy: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment strategies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:48–58. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen JA, Lewis RA. CIDP diagnostic pitfalls and perception of treatment benefit. Neurology. 2015;85:498–504. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castillo M, Mukherji SK. MRI of enlarged dorsal ganglia, lumbar nerve roots, and cranial nerves in polyradiculoneuropathies. Neuroradiology. 1996;38:516–520. doi: 10.1007/BF00626085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Es HW, van den Berg LH, Franssen H, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brachial plexus in patients with multifocal motor neuropathy. Neurology. 1997;48:1218–1224. doi: 10.1212/WNL.48.5.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goedee HS, Jongbloed BA, van Asseldonk J-TH, et al. A comparative study of brachial plexus sonography and magnetic resonance imaging in chronic inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy and multifocal motor neuropathy. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24:1307–1313. doi: 10.1111/ene.13380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jongbloed BA, Bos JW, Rutgers D, et al. Brachial plexus magnetic resonance imaging differentiates between inflammatory neuropathies and does not predict disease course. Brain Behav. 2017;7:e00632. doi: 10.1002/brb3.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosmalen MHJ, Goedee HS, Gijp A, et al. Low interrater reliability of brachial plexus MRI in chronic inflammatory neuropathies. Muscle Nerve. 2020;61:779–783. doi: 10.1002/mus.26821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oudeman J, Eftimov F, Strijkers GJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of MRI and ultrasound in chronic immune-mediated neuropathies. Neurology. 2020;94:e62–e74. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goedee HS, Van Der Pol WL, Van Asseldonk JTH, et al. Diagnostic value of sonography in treatment-naive chronic inflammatory neuropathies. Neurology. 2017;88:143–151. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goedee HS, Van Der Pol WL, Hendrikse J, Van Den Berg LH. Nerve ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of neuropathy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2018;31:526–533. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herraets IJT, Goedee HS, Telleman JA, et al. Nerve ultrasound improves detection of treatment-responsive chronic inflammatory neuropathies. Neurology. 2020;94:e1470–e1479. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herraets IJT, Goedee HS, Telleman JA, et al. Nerve ultrasound for the diagnosis of chronic inflammatory neuropathy: a multicenter validation study. Neurology. 2020 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL. El Escorial revisited: Revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. ALS Mot Neuron Disord. 2000;1:293–299. doi: 10.1080/146608200300079536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Asseldonk JTH, Van Den Berg LH, Kalmijn S, et al. Criteria for demyelination based on the maximum slowing due to axonal degeneration, determined after warming in water at 37°C: diagnostic yield in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Brain. 2005;128:880–891. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson EO, Vekris M, Demesticha T, Soucacos PN. Neuroanatomy of the brachial plexus: normal and variant anatomy of its formation. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;32:291–297. doi: 10.1007/s00276-010-0646-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasparotti R, Lucchetta M, Cacciavillani M, et al. Neuroimaging in diagnosis of atypical polyradiculoneuropathies: report of three cases and review of the literature. J Neurol. 2015;262:1714–1723. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7770-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lozeron P, Lacour MC, Vandendries C, et al. Contribution of plexus MRI in the diagnosis of atypical chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathies. J Neurol Sci. 2016;360:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fargeot G, Viala K, Theaudin M, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of plexus MRI in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculopathy without electrodiagnostic criteria of demyelination. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26:631–638. doi: 10.1111/ene.13868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jomier F, Bousson V, Viala K, et al. Prospective study of the additional benefit of plexus MRI in the diagnosis of CIDP. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:181–187. doi: 10.1111/ene.14053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tazawa K-I, Matsuda M, Yoshida T, et al. Spinal nerve root hypertrophy on MRI: clinical significance in the diagnosis of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Intern Med. 2008;47:2019–2024. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiwatashi A, Togao O, Yamashita K, et al. Evaluation of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy: 3D nerve-sheath signal increased with inked rest-tissue rapid acquisition of relaxation enhancement imaging (3D SHINKEI) Eur J Radiol. 2017;27:447–453. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka K, Mori N, Yokota Y, Suenaga T. MRI of the cervical nerve roots in the diagnosis of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: a single-institution, retrospective case-control study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003443. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su X, Kong X, Liu D, et al. Multimodal magnetic resonance imaging of peripheral nerves: establishment and validation of brachial and lumbosacral plexi measurements in 163 healthy subjects. Eur J Radiol. 2019;117:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be available on request from the corresponding author.