Abstract

Decrease of survivability and stability is a major problem affecting probiotic functional food. Thus, in this study, Lactobacillus reuteri TF-7 producing bile salt hydrolase was microencapsulated in whey protein isolate (WPI) or whey protein isolate combined with nano-crystalline starch (WPI-NCS) using the spray-drying technique to enhance the survivability and stability of probiotics under various adverse conditions. Spherical microcapsules were generated with this microencapsulation technique. In addition, the survival of L. reuteri TF-7 loaded in WPI-NCS microcapsules was significantly higher than WPI microcapsules and free cells after exposure to heat, pH, and simulated gastrointestinal conditions. During long-term storage at 4, 25, and 35 °C, WPI-NCS microcapsules could retain both survival and biological activity. These findings suggest that microcapsules fabricated from WPI-NCS provide the most robust efficiency for enhancing the survivability and stability of probiotics, in which their great potentials appropriate to develop as the cholesterol-lowering probiotic supplements.

Keywords: Lactobacillus reuteri TF-7, Probiotics, Spray-drying microencapsulation, Nano-crystalline starch, Whey protein isolate

Introduction

Functional foods containing probiotics have gained a lot of attention from consumers of all ages due to their beneficial health effects (FAO/WHO, 2002). The genus of Lactobacillus is a major member and the most commercially used probiotics because it has a mutualistic relationship with the host that plays a crucial role in a reconstitution of the natural balance of the gastrointestinal microbiota (Agrawal, 2005). According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) criteria, viable probiotic cells must maintain their adequate amount at least 6 log10 CFU/g during the shelf life of products (Ouwehand, 2017). Therefore, the application of lactobacilli in the manufacturing process of probiotic supplements is a challenging task, as the harsh conditions during the manufacturing process and long-term storage negatively affect the survivability and biological activity of probiotics (Sarao and Arora, 2017). Furthermore, when probiotics passed through the gastrointestinal tract, their survival is reduced by the effect of gastric acid, bile salt, and enzymes (Gebara et al., 2013).

Microencapsulation is biotechnology with striking efficiency to deliver and protect probiotics against various adverse conditions by entrapping probiotics within the core of microcapsules (Anal and Singh, 2007). The selections of compatible biopolymers and the suitable techniques are important to provide the most robust efficiency of microcapsules. As a cost-effective method, the spray-drying technique is widely used to produce dry powder microcapsules of probiotics. The encapsulant solution is atomized and dried rapidly during passing through a heated drying medium (Moayyedi et al., 2018). Various carrier materials have been used in spray dried probiotic formulation. Protein alone or in combination with carbohydrate is suitable encapsulant materials with steady intermolecular cross-links and high thermal resistance (Li et al., 2017).

Whey protein isolate (WPI) is a dairy protein prepared from by-products of cheese production. Besides nutritional value, WPI is an important source of functional proteins (90–96%) with good physicochemical properties that contribute to intermolecular cross-links with other biopolymers. Thus, it is commonly applied for microencapsulation to enhance product stability (Carvalho et al., 2013). To be efficacious, the combination of WPI with carbohydrate biopolymers is more selected for microencapsulation of probiotics (Devi et al., 2017).

Starch from cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) is commonly used as a raw material in a wide range of food industries due to its low cost. Native cassava starch can be modified into nano-crystalline starch (NCS) by acid hydrolysis to suit various applications. Since the amylose (19–22%) and amylopectin (28–81%) within the starch granules arrange into two structures with different physicochemical characteristics including amorphous and crystalline structures (Lin et al., 2011; Zhu, 2015). After acid hydrolysis, the residue within the granules contains the starch nanocrystals, which are suitable for applying as an encapsulant material (Ma et al., 2017). However, the use of WPI combined with NCS from cassava as an encapsulant material has not been reported. Thus, WPI combined with NCS can be considered as the novel alternative mixed biopolymers for spray-drying microencapsulation of probiotics.

Lactobacillus reuteri TF-7 used in this study was isolated from pickled olives by our laboratory. It was able to produce bile salt hydrolase (BSH) enzyme, which hydrolyzed conjugated bile salt, leading to an indirect cholesterol reduction. However, it had low resistance to gastrointestinal conditions. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate the microencapsulation efficiency and morphological characteristics of microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 using either single biopolymer (WPI) or mixed biopolymers (WPI-NCS) via the spray-drying technique. In addition, the protective efficiency of microcapsules to enhance bacterial survivability and stability was investigated under various adverse conditions.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strain and culture preparation

Lactobacillus reuteri TF-7 originally isolated from pickled olives (from the crown property market, Chachoengsao, Thailand) was stored in De Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) broth (Himedia, India) supplemented with 40% (v/v) glycerol at − 80 °C. For further use, probiotics were activated in MRS agar under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 48 h. A single colony of bacteria was inoculated into MRS broth and incubated anaerobically at 37 °C, then the optical density was measured at a wavelength of 600 nm during incubation until their propagation reached the early stationary phase. After that, bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7000×g, 4 °C for 10 min and re-suspended with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.2) at a final concentration about 10 log10 CFU/mL.

To prepare bacterial suspension for free cell control, bacterial cells were dispersed in PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.2) at 9 log10 CFU/mL for experimental use.

Modification of native cassava starch

Native cassava starch was modified following the same procedure with some modifications as described by Costa et al. (2017). Native cassava starch (50 g) obtained from Siam Quality Starch Co., Ltd. (Chaiyaphum, Thailand) was dissolved in 250 mL of 3.20 M H2SO4. The starch solution was incubated at 37 °C for 170 h with constant shaking at 120 rpm. After incubation, the starch solution was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane filter (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) to separate the modified starch granules. The acidity of starch hydrolysate was neutralized using successive centrifugation at 16,000×g, 10 °C for 10 min in deionized water until pH reached 7.0. Then, it was suspended in deionized water and homogenized at 12,000 rpm for 5 min using IKA T50 ULTRA-TURRAX Heavy Duty Homogenizer (Cole-Parmer, Wertheim, Germany). For freeze-drying, the starch hydrolysate solution was added into a round bottom flask and pre froze at − 40 °C for 10 min in the ethanol bath. After pre-freezing, the sample was dried using freeze dryer (SciQuip, UK) for overnight and then the dried powders of starch hydrolysate were collected in sterile bottles and stored at 25 °C in the auto desiccator cabinet (Thomas Scientific, Swedesboro, USA).

Analysis of morphologies and crystallinity

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to observe the morphologies of native starch and starch hydrolysate. Samples were dissolved in distilled water and placed on a carbon-coated grid. Subsequently, the stained samples were studied using JEM-1400 Flash Electron Microscope (JEOL, Boston, USA) at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV.

The structural characteristics of native starch and starch hydrolysate were analyzed using the X-ray diffraction technique to calculate the crystallinity according to the previous methods described by Chisenga et al. (2019) and Park et al. (2010) with some modifications. Briefly, the native starch and starch hydrolysate were separately loaded into sample tray and analyzed using D8 ADVANCE X-ray diffractometer (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) under the measurement conditions at a CuKα radiation wavelength of 1.5406 Å and the diffraction angle of scanning range from 4 to 40°2θ with counting for 0.02°/s. Subsequently, X-ray diffractogram was analyzed to subtract the amorphous portion, then the crystalline peaks were extracted with the Gaussian method using OriginPro software version 9.1 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA). The percentage of relative crystallinity was calculated according to the equation:

where Ac is the area of crystalline portion and Aca is the area of crystalline and amorphous portions.

Microencapsulation of L. reuteri TF-7 via spray-drying technique

The preparation of microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 was performed according to the previous method with modifications (Liu et al., 2016). In this study, WPI was donated by the Vicchi Enterprise Co., Ltd. (Suanluang, Bangkok, Thailand). The encapsulant solution was prepared using either WPI or WPI-NCS (at a weight ratio of 4:1) formula at a final total solid of 7%. Initially, either 35 g (WPI formula) or 28 g (WPI-NCS formula) of WPI was dissolved in 500 mL of deionized water and then they were stirred at 250 rpm for 30 min to dissolve completely. To prepare the mixed encapsulant solution of WPI combined with NCS (starch hydrolysate), 7 g of NCS was added in the WPI solution of WPI-NCS formula. These encapsulant solutions were kept refrigerated at 4 °C for 12 h. After that, the pH of encapsulant solutions was adjusted to 7.5 with 5 M NaOH, then they were heated at 90 °C for 10 min with constant stirring at 250 rpm. After cooling down, 0.5 g of gum arabic (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was added into 500 mL of the encapsulant solutions both WPI and WPI-NCS formulas, followed by homogenization at 12,000 rpm for 10 min to stabilize the colloidal condition. Subsequently, 50 mL of bacterial cell suspension (10 log10 CFU/mL) was added in 450 mL of each encapsulant solution and gently mixed to gain a final cell loading at least 9 log10 CFU/mL. The spray-drying technique was used in this study to produce dry powder microcapsules. The encapsulant-cell solutions were dried using mini spray dryer B-290 (Buchi, Flawil, Switzerland) under the conditions at an air inlet temperature of 120 °C, air outlet temperature of 75 °C, feed flow rate of 0.27 L/h, and atomization air flow rate of 35 m3/h. The microcapsule powders were collected from the cyclone chamber to sterile bottles and stored in the auto desiccator cabinet.

Determination of microencapsulation efficiency and powder yield

One gram of microcapsules was dispersed in 10 mL of PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.2) with stirring for 20 min to release bacterial cells. They were serially diluted tenfold, spread on MRS agar plates, and incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 48 h (Eckert et al., 2017). The percentage of microencapsulation efficiency was calculated using the following equation:

where N is the number of viable bacteria in the microcapsules after spray-drying and N0 is the number of viable bacteria in the encapsulant solution before spray-drying.

After the spray-drying process, the mass of dry powder was measured to calculate the percentage of powder yield according to the equation:

where M is the mass of dry powder and M0 is the mass of encapsulant materials used.

Morphological analysis of microcapsules

The morphologies of microcapsules were studied by scanning electron microscope (SEM). Bacterial cells and microcapsules were placed on carbon conductive tape and coated with gold nanoparticles by Hitachi E-1045 Ion Sputter Coater (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). After that, their morphologies were determined using Hitachi SU8010 Scanning Electron Microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

Growth characterization of free cells and microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7

The effect of microencapsulation on the growth of probiotics was evaluated by the determination of probiotic propagation in MRS broth (Yao et al., 2017). Free cells (1 g) and microcapsules (1 g) were separately inoculated into 100 mL of MRS broth and incubated anaerobically at 37 °C. During incubation, the optical density (600 nm) of MRS broth was continuously measured every 2 h until their growth reached to stationary phase.

Survivability of free cells and microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 after heat and pH treatment

The protective efficiency of microcapsules after exposure to heat and pH conditions was determined according to the previous methods described by Matos-Jr et al. (2019) and Yao et al. (2017) with minor modifications. For heat treatment, free cells (1 g) and microcapsules (1 g) were separately inoculated into 10 mL of PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.2) and heated at 45 and 63 °C for 30 min. After that, they were cooled down at 25 °C immediately. For pH treatment, free cells (1 g) and microcapsules (1 g) were separately inoculated into 10 mL of each adjusted PBS (0.1 M) with 1 M HCl or 1 M NaOH at pH 3.0, 6.0, and 9.0 and then incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, they were serially diluted tenfold, spread on MRS agar plates, and incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 48 h. The survival bacteria were counted and calculated as log10 CFU/g. The untreated sample was used as a control.

Survivability of free cells and microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 after sequential incubation under the simulated gastrointestinal conditions

The simulated gastric and intestinal juices were prepared to evaluate the protective efficiency of microcapsules on enhancing the survival of probiotics under the gastrointestinal conditions, following the previous method of Jing et al. (2011) with minor modifications. Initially, the simulated gastric juice (SGJ) was prepared in 50 mL of 0.2% (w/v) NaCl solution containing 0.17 g of pepsin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) and then the pH was adjusted to 2.0 with 1 M HCl. For preparing the simulated intestinal juice (SIJ), 50 mL of 0.2% (w/v) NaCl solution was supplemented with 0.5 g of bovine bile (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), 0.05 g of trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), and 0.55 g of NaHCO3, then the pH was adjusted to 8.0 with 1 M NaOH. These simulated gastrointestinal juices were filtered by a 0.22 μm membrane filter to sterilize the solution. Free cells (1 g) and microcapsules (1 g) were separately added into 10 mL of the SGJ, followed by anaerobic incubation at 37 °C for 3 h with constant shaking. Subsequently, the pellet was harvested by centrifugation at 5000×g, 4 °C for 10 min, re-suspended with the SIJ, and incubated anaerobically at the same conditions. One milliliter of the samples was collected every 1 h and dispersed in 9 mL of PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.2). The survival bacteria were determined and calculated as log10 CFU/g by using the serial dilution–agar plate method as explained above.

Stability of free cells and microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 during long-term storage

Stability of free cells and microcapsules was determined during long-term storage at 4, 25, and 35 °C for 12 weeks. During storage, 1 g of the samples was collected every 1 week and dispersed in 10 mL of PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.2). The survival bacteria were determined and calculated as log10 CFU/g by using the serial dilution–agar plate method as explained above. Besides survivability, the stability of biological activity to produce BSH was determined by the qualitative spot plate technique (Moser and Savage, 2001). Briefly, 10 μL of free cells and microcapsules dispersed with PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.2) was spotted on modified MRS agar containing 0.5% (w/v) sodium salt of tauro-deoxycholic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), followed by anaerobic incubation at 37 °C for 72 h. After that, the diameter of precipitation zone (deconjugated bile salt precipitates) was measured.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed with three replicates. The experimental results were expressed as means ± standard deviation. The independent t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests were used to analyze the significant differences with p < 0.05 using GraphPad Prism software version 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results and discussion

Morphologies and relative crystallinity of NCS

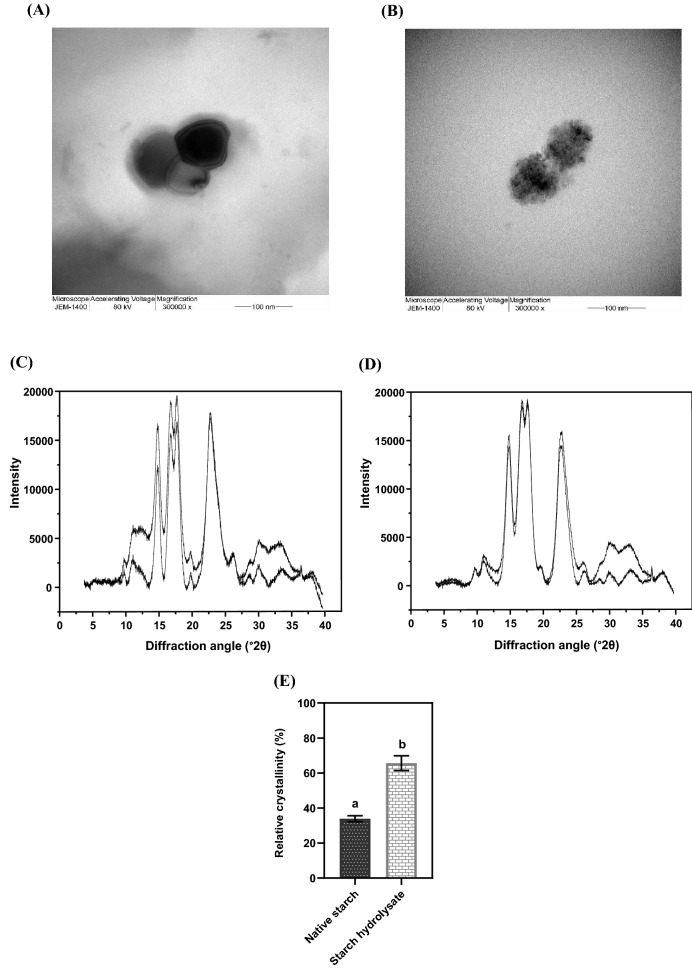

From the TEM morphologies (Fig. 1A and B), the region of crystalline structure was observed in starch hydrolysate with a size of about 100 nm. In contrast, native starch showed a polygonal shape with smooth surfaces. The crystallinity was proven by X-ray diffraction technique. As shown in Fig. 1C and D, X-ray diffractograms of native starch and starch hydrolysate exhibited the crystalline and amorphous portions (upper graph). After extracting the crystalline peaks, the crystalline portion could be observed (lower graph). The relative crystallinity of starch hydrolysate (65.61 ± 4.22%) significantly increased (p < 0.05), compared with the native starch (33.91 ± 1.66%) (Fig. 1E). These results illustrated that the amorphous structure was hydrolyzed by sulfuric acid under the proper conditions (37 °C for 170 h with constant shaking). After acid hydrolysis, the nanocrystal residue remained within the starch hydrolysate granules, which was called NCS (Costa et al., 2017). Synthesize native starch into NCS affects the changes in physicochemical properties. A study by Xia et al. (2017) showed that once the native starch was hydrolyzed, its average molecular weight decreased from 2.19 × 107 g/mol to 1.37 × 104 g/mol, which corresponded with an increase in crystallinity. The strong interfacial interactions within the crystalline network result in reinforcing of NCS and hence enhance the rigid crystalline endurance and mechanical strength (Lin et al., 2011; Md Shahrodin et al., 2015). Costa et al. (2017) reported that the values of melting temperature, glass transition temperature, and gelatinization temperature were 229, 219.82, and 63.43 °C for native starch, and 227, 223.63, and 96.57 °C for NCS, indicating that NCS had greater thermal stability. Moreover, the orderly arrangement of crystalline structure in a double helix form facilitates the interaction with protein biopolymers (Chinma et al., 2013; Zhu, 2015). Therefore, NCS may be a potential biopolymer in terms of protecting the probiotics and suitable for incorporating with WPI.

Fig. 1.

TEM morphologies of native starch (A) and starch hydrolysate (B) with 300,000×magnification. X-ray diffractogram (upper graph) and the extracted crystalline peaks (lower graph) of native starch (C) and starch hydrolysate (D). The percentage of relative crystallinity was compared between native starch and starch hydrolysate (E). Error bars represent standard deviations of means (n = 3). The different lowercase letters indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05)

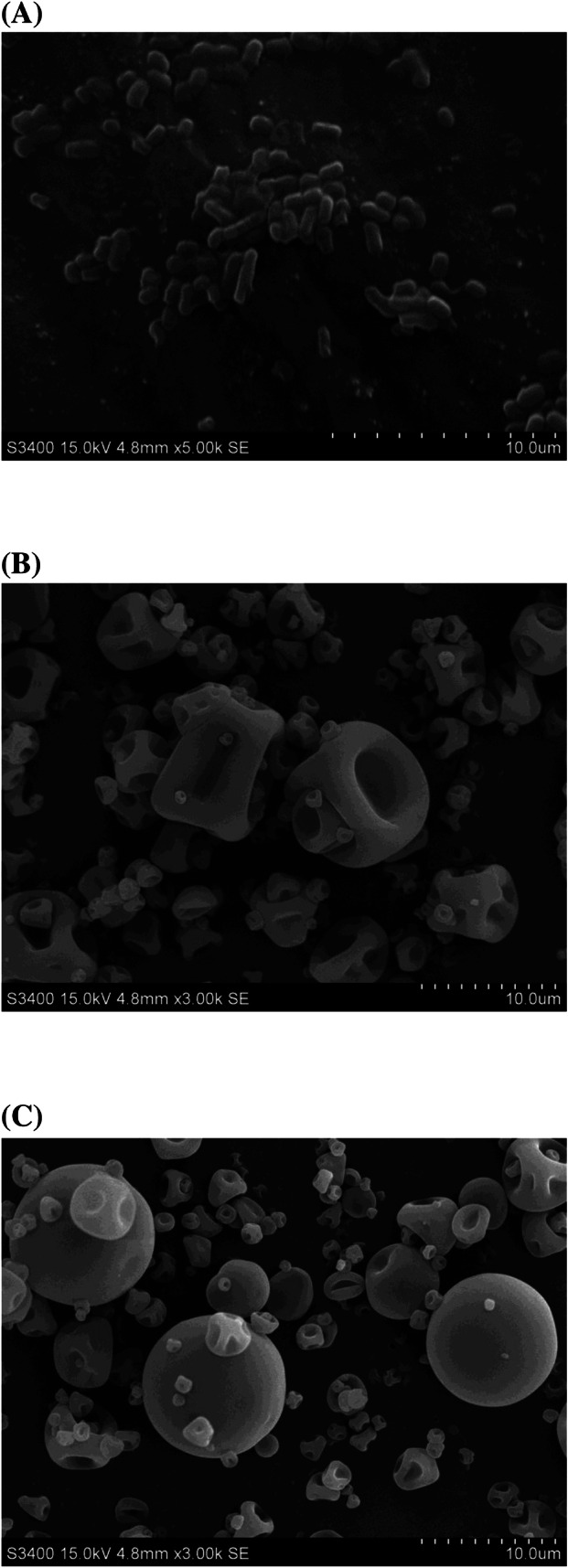

Microencapsulation efficiency, powder yield, and morphological characteristics

As illustrated in Table 1, there was no difference in the microencapsulation efficiency and powder yield between WPI and WPI-NCS microcapsules. The viability of microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 both WPI and WPI-NCS microcapsules slightly decreased after spray-drying. Nevertheless, the number of viable bacteria was still close to 9 log10 CFU/g and the microencapsulation efficiency was greater than 90%, which is sufficient to a great extent for industrial use. These results were in agreement with previous study that reported no significant difference in the microencapsulation efficiency of L. rhamnosus GG in whey protein alone (8.60 ± 0.30 log10 CFU/100 mL) compared with whey protein combined with resistant starch at 4:1 (8.80 ± 0.00 log10 CFU/100 mL) (Ying et al., 2013). Considering the morphological characteristics, bacterial sizes ranged around 2–3 μm (Fig. 2A), whereas WPI and WPI-NCS microcapsule particle sizes varied within the range of 4–20 μm (Fig. 2B and C). Their morphologies appeared to be relatively spherical shapes and smooth wall surfaces without pores and fissures. These characteristics are good physical features of wall structure which can inhibit the penetration of the adverse factors from the external environment. Despite their similarity, the large microcapsules of WPI (Fig. 2B) were observed to be more shrinking than WPI-NCS (Fig. 2C), resulting from moisture loss during the spray-drying process. Also, the different sizes of particles were influenced by the conditions of the spray-drying process such as flow rate, atomization pressure, and spray nozzle.

Table 1.

Microencapsulation efficiency and powder yield of microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7

| Microcapsules | Viable bacteria (log10 CFU/g) | Microencapsulation efficiency (%) | Powder yield (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before spray-drying | After spray-drying | |||

| WPI | 9.53 ± 0.29 | 8.88 ± 0.02 | 93.28 ± 2.69a | 64.10 ± 2.29a |

| WPI-NCS | 9.32 ± 0.14 | 8.93 ± 0.01 | 95.83 ± 1.53a | 63.33 ± 0.78a |

Results are presented as means ± standard deviations (n = 3). The different lowercase superscript letters within the same column represent statistical significance (p < 0.05)

Fig. 2.

SEM morphologies of free cells and microcapsules with different magnifications: free cells ×5000 (A), WPI microcapsules ×3000 (B), and WPI-NCS microcapsules ×3000 (C)

Considering these results together, even though WPI alone was sufficiently effective for probiotic microencapsulation, but WPI-NCS microcapsules tended to be more effective than WPI microcapsules. It demonstrated that WPI played a crucial role in the microencapsulation. Since the chemical compositions of WPI contain 90–96% of functional proteins (β-lactoglobulin, α-lactalbumin, and serum albumin), 0.5–1% of fat, and 0.2–1% of lactose, which determine the physicochemical characteristics of WPI. The distinct amino acid side chains in these major proteins form the intermolecular cross-links and hold their molecules in proximity to increase the structural integrity (Qi and Onwulata, 2011). Furthermore, their molecular structures, particularly β-lactoglobulin and α-lactalbumin, can modify the physicochemical reactions (e.g., electrostatic interactions, hydrophobic interactions, disulfide bonds) upon heating at neutral pH, leading to disclosing the functional groups within the denatured protein and sensitive behavior for interaction with carbohydrate biopolymers under the proper conditions (Aragón-Rojas et al., 2018; Madureira et al., 2010). Meanwhile, strong intermolecular interactions between protein biopolymers and NCS result in enhancing mechanical strength, thermal stability, and barrier function of biopolymer network (Lin et al., 2011). Thus, the supplementation with NCS could maintain the stability and mechanical performance of wall structure during the spray-drying process as well as microencapsulation efficiency. Some studies have suggested that WPI combined with carbohydrate biopolymers were able to enhance the protective potential in addition to the provision of microencapsulation efficiency (Martinez-Alvarenga et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016).

As mentioned above, WPI-NCS microcapsules may have better potential than WPI microcapsules for improving the survivability and stability of L. reuteri TF-7. However, the result of this study is quite satisfactory for spray-drying microencapsulation using WPI and WPI-NCS, which was compatible with L. reuteri TF-7.

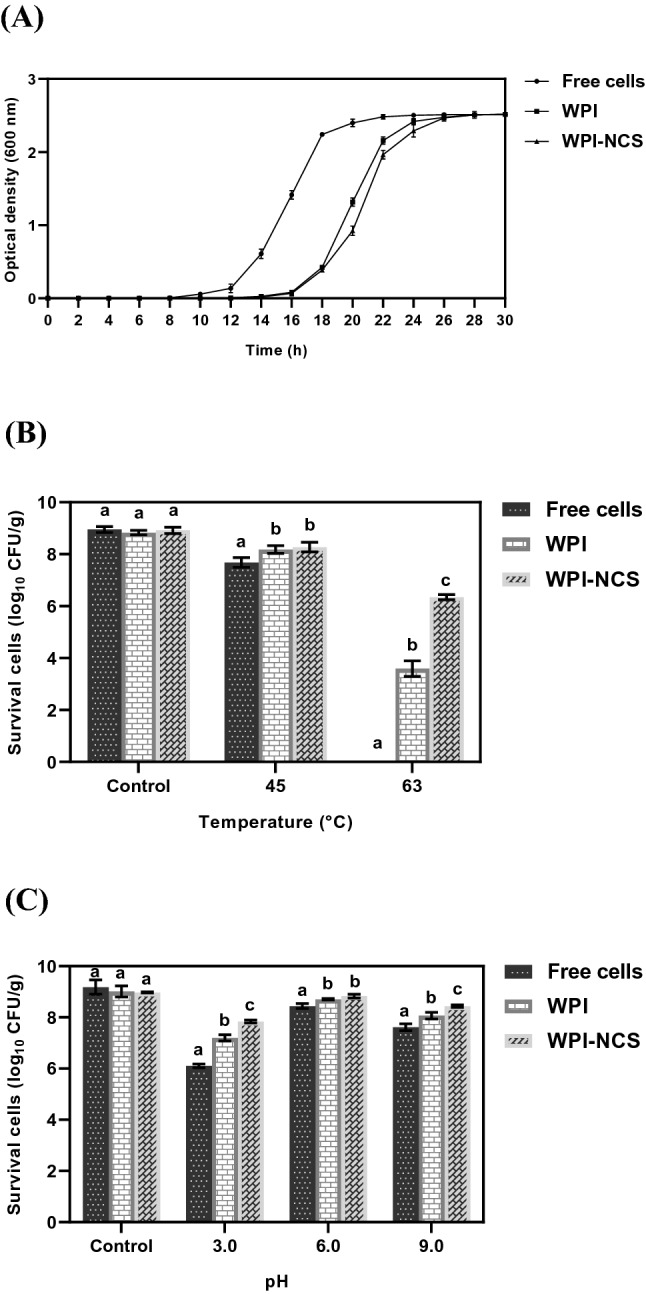

Effect of microencapsulation on modulating growth of L. reuteri TF-7

Probiotic propagation in MRS broth was used to determine the growth characteristics of free cells and microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 after spray-drying microencapsulation. As shown in Fig. 3A, similar growth rates were observed in microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 both WPI and WPI-NCS microcapsules when compared with free cells. However, the exponential phase of microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 was shifted to a longer time of about 4 h, compared with free cells. WPI and WPI-NCS microcapsules were able to release entrapped probiotic cells without growth inhibition effect. The prolonged period at the exponential phase of microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 may result from the gradual disintegration of wall structure during dispersion in MRS broth, which leads to slow liberation of entrapped probiotic cells before they grow. This result was similar to the previous study that reported the longer exponential period at about 3 h of microencapsulated L. salivarious Li01 in alginate and gelatin when compared with free cells (Yao et al., 2017). The result of this study proved that the microencapsulation process did not negatively affect the growth of L. reuteri TF-7.

Fig. 3.

Growth characteristics of free cells and microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 (A) and the survival of free cells and microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 after exposure to different heat conditions (B) and pH conditions (C). Error bars represent standard deviations of means (n = 3). The different lowercase letters indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05)

Effect of microencapsulation on enhancing the survivability of L. reuteri TF-7 after heat and pH treatment

The protective efficiency of microcapsules on the adverse conditions of the manufacturing process was determined under several heat and pH conditions. For heat treatment, the survival of bacteria was measured after heating at 45 and 63 °C for 30 min. These temperatures are usually applied in the heat-treatment process, especially pasteurization, to preserve and extend shelf life. As shown in Fig. 3B, the survivals of microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 both WPI and WPI-NCS microcapsules as well as free cells gradually decreased upon increasing the temperature. In particular, after heating at 63 °C, the survivals of L. reuteri TF-7 loaded in WPI and WPI-NCS microcapsules were 3.59 ± 0.30 log10 CFU/g (40.71 ± 3.29%) and 6.34 ± 0.10 log10 CFU/g (71.15 ± 1.84%), respectively, whereas the survival of free cells was not found. Obviously, L. reuteri TF-7 loaded in WPI-NCS microcapsules had the highest survival with statistically significant (p < 0.05) after heating at 45 and 63 °C, compared with WPI microcapsules and free cells. This result was in agreement with previous study reported by Yao et al. (2017) that the mixed biopolymers provided better heat-resistance than single biopolymer. The highest number of survival cells after heating at 63 °C for 30 min was observed in microencapsulated L. salivarious Li01 in sodium alginate coated with gelatin when compared with alginate alone (Yao et al., 2017).

The various pH values used in this study cover the adverse pH values of the manufacturing process, as shown in Fig. 3C. Free cells and microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 exhibited a reduction of survival after exposure to pH conditions, especially pH 3.0 and 9.0. However, the survival of L. reuteri TF-7 loaded in WPI-NCS microcapsules was significantly higher than that of WPI microcapsules and free cells (p < 0.05). On the other hand, the survivals after exposure to pH 6.0 of free cells, WPI, and WPI-NCS microcapsules were 8.44 ± 0.10 log10 CFU/g (91.97 ± 3.42%), 8.71 ± 0.03 log10 CFU/g (96.63 ± 2.03%), and 8.83 ± 0.07 log10 CFU/g (98.40 ± 0.93%), respectively. The differences were minor due to pH used in this condition which was close to an optimal pH of L. reuteri TF-7 (pH 5.8). Similarly, increases in microcapsule stability were observed in microencapsulation using lipid particles coated with gelatin-gum arabic mixture of L. paracasei BGP1 and L. rhamnosus 64 under various pH values, especially low pH values (Matos-Jr et al., 2019).

Based on these results, microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 using WPI and WPI-NCS clearly improved its survivability under heat and pH conditions. Moreover, WPI-NCS microcapsules were more effective than WPI microcapsules. Interestingly, after heating at pasteurization conditions, the survival of L. reuteri TF-7 loaded in WPI-NCS microcapsules remained an adequate amount above 6 log10 CFU/g, which was in accordance with the FDA guidelines (Ouwehand, 2017). The use of WPI combined with NCS may contribute to good physicochemical properties of wall structure that cannot be found from WPI alone due to the synergism between the buffering capability of WPI and thermal stability of NCS. These findings indicated that WPI combined with NCS could enhance the protective efficiency of microcapsules to be tolerant to high temperature and pH conditions during the manufacturing process.

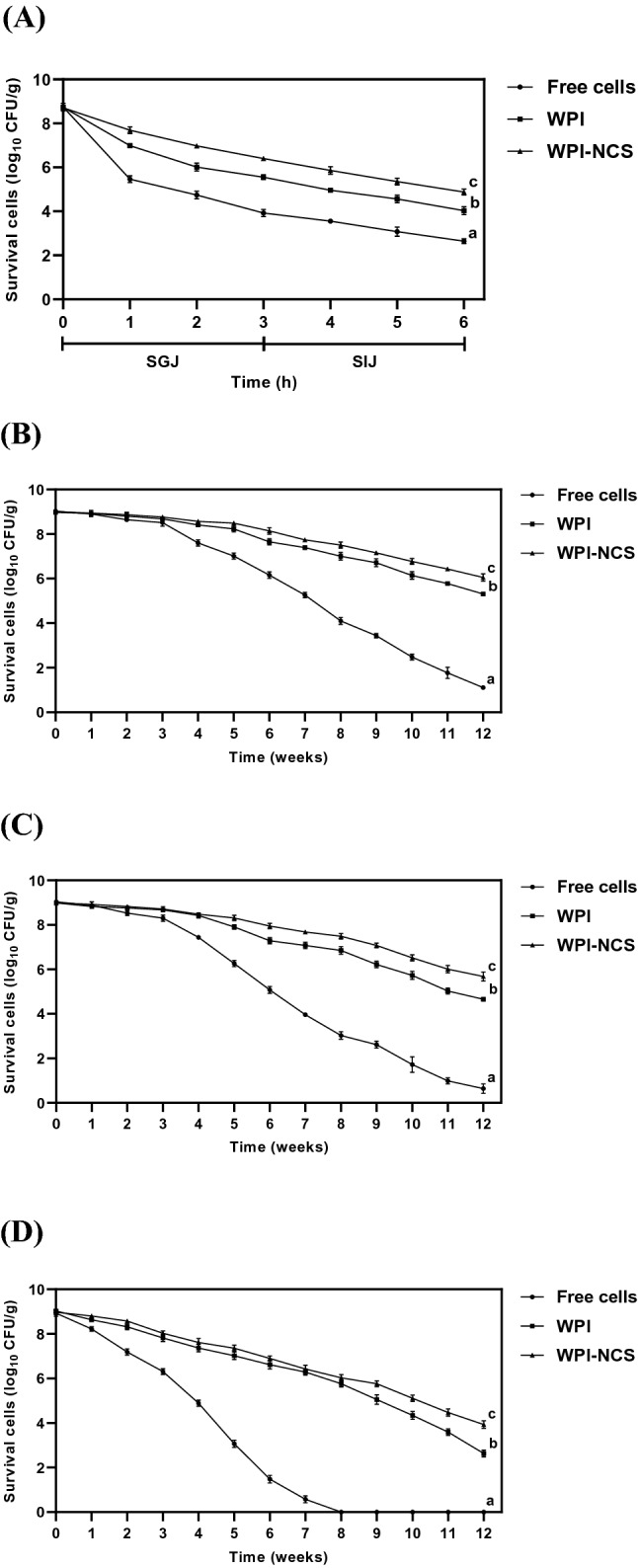

Effect of microencapsulation on enhancing the survivability of L. reuteri TF-7 under the simulated gastrointestinal conditions

The gastrointestinal conditions were simulated to investigate the protective efficiency of microcapsules on the adverse conditions when administered probiotics passing through the gastrointestinal tract. As shown in Fig. 4A, the survivals of free cells and microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 gradually reduced in a time-dependent manner after incubation with the SGJ solution for 3 h. However, the highest and the second-highest survivals of L. reuteri TF-7 with statistically significant (p < 0.05) were observed in WPI-NCS (6.40 ± 0.05 log10 CFU/g, 73.45 ± 1.34%) and WPI microcapsules (5.55 ± 0.11 log10 CFU/g, 63.51 ± 0.87%), respectively. At the end of sequential incubation in the SIJ solution for 3 h (for 6 h of total incubation time), the survivals of free cells, WPI, and WPI-NCS microcapsules were 2.64 ± 0.11 log10 CFU/g (30.22 ± 1.44%), 4.03 ± 0.18 log10 CFU/g (46.19 ± 2.09%), and 4.88 ± 0.14 log10 CFU/g (56.03 ± 1.68%), respectively, which were significantly different (p < 0.05). Similarly, Cabuk and Harsa (2015) demonstrated that the use of whey protein and pullulan in combination to form microcapsules expressed high efficiency to protect L. acidophilus NRRL B-4495 (8.03 log10 CFU/g, 87.18%) than whey protein alone (7.56 log10 CFU/g, 80.04%) and free cells (6.67 log10 CFU/g, 73.19%) after incubation in the SGJ solution. L. acidophilus NRRL B-4495 loaded in whey protein combined with pullulan microcapsules (8.52 log10 CFU/g, 91.91%) also exhibited higher survival than whey protein alone (7.71 log10 CFU/g, 86.34%) and free cells (7.10 log10 CFU/g, 76.26%) after incubation in the SIJ solution.

Fig. 4.

Survival of free cells and microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 during sequential incubation under the simulated gastrointestinal conditions (A) and long-term storage at 4 °C (B), 25 °C (C), and 35 °C (D) for 12 weeks. Error bars represent standard deviations of means (n = 3). The different lowercase letters indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05)

In this study, the adverse conditions in the gastrointestinal tract influenced microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 to a certain extent upon extending the incubation time. Gastric acid and enzyme can hydrolyze the cellular macromolecules. Also, bile salt can degrade phospholipid within the cell membrane, leading to cell lysis. However, microencapsulation of L. reuteri TF-7 using WPI and WPI-NCS was successful to enhance the survivability under the simulated gastrointestinal conditions. WPI-NCS microcapsules also exhibited the most robust protective efficiency, allowing them to resist the adverse conditions better than WPI microcapsules. This result demonstrated that the supplementation with NCS could promote the efficiency of WPI to protect L. reuteri TF-7 from these adverse conditions. The ability of WPI and NCS in terms of protecting the probiotics depends on their physicochemical properties. The buffering capability of WPI may neutralize the gastric acid to maintain some intact microcapsules, while the modified structure of NCS relatively resists the digestion of gastric enzyme, contributing to promoting the structural integrity of microcapsules. Moreover, the biopolymer network within the wall structure of microcapsules may retard the diffusion of digestive enzymes and bile salt during intestinal transit (Ye et al., 2019; Zou et al., 2012).

Effect of microencapsulation on enhancing the stability of L. reuteri TF-7 during long-term storage

The required storage condition for probiotic supplements during transportation is 4 °C to maintain their potential probiotic properties. Once the products are released into the market, they are often stored at ambient temperature (25 °C in rainy season, 35 °C in summer season) or in refrigerated storage. Therefore, free cells and microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 were determined the stability under the conditions at 4, 25, and 35 °C to imitate the storage conditions of commercial products. The result is shown in Fig. 4B, C, and D, the survival of L. reuteri TF-7 loaded in WPI-NCS microcapsules was significantly higher than WPI microcapsules and free cells (p < 0.05) throughout the storage at 4, 25, and 35 °C. Considering the final week of storage at 4 °C, the survivals of free cells, WPI, and WPI-NCS microcapsules were 1.11 ± 0.08 log10 CFU/g (12.29 ± 0.90%), 5.31 ± 0.09 log10 CFU/g (59.17 ± 0.96%), and 6.05 ± 0.16 log10 CFU/g (67.20 ± 1.45%), respectively. For final week of storage at 25 °C, their survivals were 0.64 ± 0.21 log10 CFU/g (7.11 ± 2.31%), 4.66 ± 0.08 log10 CFU/g (51.80 ± 0.90%), and 5.68 ± 0.20 log10 CFU/g (63.15 ± 2.46%), respectively. However, it should be noted that the survival of free cells was preserved up to 7 weeks (0.58 ± 0.16 log10 CFU/g (6.51 ± 1.90%)) after storage at 35 °C, whereas the survivals of WPI and WPI-NCS microcapsules were 2.63 ± 0.16 log10 CFU/g (29.08 ± 1.21%) and 3.93 ± 0.17 log10 CFU/g (43.85 ± 1.09%) at 12 weeks, respectively. This result was similar to the previous study reported that the microencapsulation using whey protein combined with pullulan (7.91 ± 0.21 log10 CFU/g, 82.80 ± 0.43%) exhibited the most efficient condition to extend the stability of L. acidophilus NRRL B-4495 during storage at 4 °C for 4 weeks, compared with whey protein microcapsules (7.87 ± 0.31 log10 CFU/g, 81.89 ± 0.53%) and free cells (5.55 ± 0.21 log10 CFU/g, 57.92 ± 0.23%) (Cabuk and Harsa, 2015).

Apart from survivability, the biological activity of free cells and microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 expressed the ability to produce BSH throughout the storage at 4, 25, and 35 °C (Table 2). Although microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 exhibited higher BSH activity than that of free cells, the reduction of BSH was observed almost at the end of storage period. This result was in accordance with the reduction of survivability.

Table 2.

Biological activity of free cells and microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 to produce BSH during long-term storage

| Weeks | BSH activity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storage at 4 °C | Storage at 25 °C | Storage at 35 °C | |||||||

| Free cells | WPI | WPI-NCS | Free cells | WPI | WPI-NCS | Free cells | WPI | WPI-NCS | |

| 0 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| 1 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| 2 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| 3 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| 4 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| 5 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| 6 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | +++ |

| 7 | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | +++ |

| 8 | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ND | +++ | +++ |

| 9 | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ND | +++ | +++ |

| 10 | ++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | +++ | ND | ++ | +++ |

| 11 | + | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | +++ | ND | ++ | ++ |

| 12 | + | +++ | +++ | + | ++ | +++ | ND | + | ++ |

BSH activity was interpreted based on the diameter of precipitation zone (n = 3, means ± SD): ND, no zone; + , ≤ 8.0 mm (weak); ++, 8.1–13.0 mm (moderate); +++, ≥ 13.1 mm (strong)

Based on these results, the stability of L. reuteri TF-7 both survivability and biological activity during long-term storage was successfully enhanced by WPI and WPI-NCS microcapsules, with WPI-NCS microcapsules again being the most protective efficiency. It is well accepted that there are several adverse conditions affecting the stability of probiotics during storage. The biopolymer network within WPI-NCS microcapsules may express the barrier function to inhibit the diffusion of disruptive molecules (particularly oxygen and moisture). This works better than WPI microcapsules because of its smooth surface with no pores and fissures. Whey lactose and the polysaccharide chains of NCS are able to bind the polar amino acids of peripheral proteins to maintain the integrity of cell membrane, resulting in inhibition of cellular metabolism of entrapped probiotics (dormant cells) (Aragón-Rojas et al., 2018; Jantzen et al., 2013). These mechanisms illustrated the most robust protective efficiency of WPI-NCS microcapsules in this study.

However, the physicochemical changes of wall structure proceeded gradually in a time-dependent manner, leading to a decrease in the efficiency of probiotic protection. Since some disruptive molecules, pH changes, and mechanical stresses contribute to the deterioration of the biopolymer network and disturbance of the microenvironment serving probiotics within the microcapsules (Sarao and Arora, 2017). Low temperature can induce the dormant state of cells by reducing the metabolic rate. It can also preserve the integrity of wall structure. Therefore, the refrigerated storage was more suitable than ambient storage to promote the stability of L. reuteri TF-7, which extended the shelf life of probiotic products.

In summary, the spray-drying microencapsulation using WPI and WPI-NCS was greatly successful to produce dry powder form of microencapsulated L. reuteri TF-7 producing BSH with good efficiency and morphologies. NCS modified from cassava starch incorporated perfectly with WPI. This combination provided the most efficiency to enhance the survivability and stability of L. reuteri TF-7 under the adverse conditions of the manufacturing process, gastrointestinal conditions, and long-term storage without interfering growth of L. reuteri TF-7. Furthermore, this study indicated that the microencapsulation of L. reuteri TF-7 using WPI-NCS in combination with refrigerated storage was the best conditions, resulting in the elevation of the adequate amount of probiotics and biological activity to produce BSH. Overall, these findings suggest that the spray-drying microencapsulation of L. reuteri TF-7 using WPI combined with NCS can be developed as the probiotic functional food with the ability to reduce cholesterol levels by BSH activity.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Research and Researchers for Industries Program, Thailand Science Research and Innovation (Grant Number PHD61I0020), and the Faculty of Medicine and HRH Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Medical Center, Srinakharinwirot University (Grant Number 219/2560). The authors thank Siam Quality Starch Co., Ltd. for providing native cassava starch and Vicchi Enterprise Co., Ltd. for the donation of whey protein isolate.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Narathip Puttarat, Email: narathipputtarat@gmail.com.

Suppasin Thangrongthong, Email: suppasin.trt@gmail.com.

Kittiwut Kasemwong, Email: kittiwut@nanotec.or.th.

Paramaporn Kerdsup, Email: paramapornk@g.swu.ac.th.

Malai Taweechotipatr, Email: malai@g.swu.ac.th.

References

- Agrawal R. Probiotics: An emerging food supplement with health benefits. Food Biotechnol. 2005;19:227–246. doi: 10.1080/08905430500316474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anal AK, Singh H. Recent advances in microencapsulation of probiotics for industrial applications and targeted delivery. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2007;18:240–251. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2007.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aragón-Rojas S, Quintanilla-Carvajal MX, Hernández-Sánchez H. Multifunctional role of the whey culture medium in the spray-drying microencapsulation of lactic acid bacteria. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2018;56:381–397. doi: 10.17113/ftb.56.03.18.5285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabuk B, Harsa ST. Protection of Lactobacillus acidophilus NRRL-B 4495 under in vitro gastrointestinal conditions with whey protein/pullulan microcapsules. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2015;120:650–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho F, Prazeres AR, Rivas J. Cheese whey wastewater: Characterization and treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;445:385–396. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinma CE, Ariahu CC, Abu JO. Chemical composition, functional and pasting properties of cassava starch and soy protein concentrate blends. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013;50:1179–1185. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0451-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisenga SM, Workneh TS, Bultosa G, Laing M. Characterization of physicochemical properties of starches from improved cassava varieties grown in Zambia. AIMS Agric. Food. 2019;4:939–966. [Google Scholar]

- Costa ÉKC, Souza CO, Silva JBA, Druzian JI. Hydrolysis of part of cassava starch into nanocrystals leads to increased reinforcement of nanocomposite films. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017;134:45311. doi: 10.1002/app.45311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devi N, Sarmah M, Khatun B, Maji TK. Encapsulation of active ingredients in polysaccharide-protein complex coacervates. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;239:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert C, Serpa VG, Santos ACF, Costa SM, Dalpubel V, Lehn DN, Souza CFV. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC 8014 through spray drying and using dairy whey as wall materials. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017;82:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.04.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO. Joint FAO/WHO (Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization) Working Group Report on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food. Ontario: London (2002)

- Gebara C, Chaves KS, Ribeiro MCE, Souza FN, Grosso CRF, Gigante ML. Viability of Lactobacillus acidophilus La5 in pectin–whey protein microparticles during exposure to simulated gastrointestinal conditions. Food Res. Int. 2013;51:872–878. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jantzen M, Gopel A, Beermann C. Direct spray drying and microencapsulation of probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri from slurry fermentation with whey. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013;115:1029–1036. doi: 10.1111/jam.12293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing W, Haifeng J, Dongyan Z, Hui L, Sixin W, Dacong S, Yamin W. Assessment of probiotic properties of Lactobacillus plantarum ZLP001 isolated from gastrointestinal tract of weaning pigs. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011;10:11303–11308. doi: 10.5897/AJB11.255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Woo WM, Patel H, Selomulya S. Enhancing the stability of protein-polysaccharides emulsions via Maillard reaction for better oil encapsulation in spray-dried powders by pH adjustment. Food Hydrocoll. 2017;69:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.01.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N, Huang J, Chang PR, Anderson DP, Yu J. Preparation, modification, and application of starch nanocrystals in nanomaterials: A review. J. Nanomater. 2011;2011:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Li X, Zhu Y, Bora AFM, Zhao Y, Li D, Bi W. Effect of microencapsulation with Maillard reaction products of whey proteins and isomaltooligosaccharide on the survival of Lactobacillus rhamnosus. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016;73:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.05.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Cheng Y, Qin X, Guo T, Deng J, Liu X. Hydrophilic modification of cellulose nanocrystals improves the physicochemical properties of cassava starch-based nanocomposite films. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017;86:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madureira AR, Tavares T, Gomes AMP, Pintado ME, Malcata FX. Invited review: Physiological properties of bioactive peptides obtained from whey proteins. J. Dairy Sci. 2010;93:437–455. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Alvarenga MS, Martinez-Rodriguez EY, Garcia-Amezquita LE, Olivas GI, Zamudio-Flores PB, Acosta-Muniz CH, Sepulveda DR. Effect of Maillard reaction conditions on the degree of glycation and functional properties of whey protein isolate – maltodextrin conjugates. Food Hydrocoll. 2014;38:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matos-Jr FE, Silva MP, Kasemodel MGC, Santos TT, Burns P, Vinderola G, Favaro-Trindade CS. Evaluation of the viability and the preservation of the functionality of microencapsulated Lactobacillus paracasei BGP1 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus 64 in lipid particles coated by polymer electrostatic interaction. J. Funct. Foods. 2019;54:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Md Shahrodin NS, Rahmat AR, Arsad A. Synthesis and characterization of cassava starch nanocrystals by hydrolysis method. Adv. Mat. Res. 2015;1113:446–452. [Google Scholar]

- Moayyedi M, Eskandari MH, Rad AHE, Ziaee E, Khodaparast MHH, Golmakani MT. Effect of drying methods (electrospraying, freeze drying and spray drying) on survival and viability of microencapsulated Lactobacillus rhamnosus ATCC 7469. J. Funct. Foods. 2018;40:391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moser SA, Savage DC. Bile salt hydrolase activity and resistance to toxicity of conjugated bile salts are unrelated properties in lactobacilli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;67:3476–3480. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.8.3476-3480.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouwehand AC. A review of dose-responses of probiotics in human studies. Benef. Microbes. 2017;8:143–151. doi: 10.3920/BM2016.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Baker JO, Himmel ME, Parilla PA, Johnson DK. Cellulose crystallinity index: Measurement techniques and their impact on interpreting cellulase performance. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2010;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi PX, Onwulata CI. Physical properties, molecular structures, and protein quality of texturized whey protein isolate: Effect of extrusion moisture content. J. Dairy Sci. 2011;94:2231–2244. doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-3942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarao LK, Arora M. Probiotics, prebiotics, and microencapsulation: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017;57:344–371. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2014.887055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H, Li BZ, Gao Q. Effect of molecular weight of starch on the properties of cassava starch microspheres prepared in aqueous two-phase system. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;177:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao M, Wu J, Li B, Xiao H, McClements DJ, Li L. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus salivarious Li01 for enhanced storage viability and targeted delivery to gut microbiota. Food Hydrocoll. 2017;72:228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.05.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Q, Woo MW, Selomulya C. Modification of molecular conformation of spray-dried whey protein microparticles improving digestibility and release characteristics. Food Chem. 2019;280:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying D, Schwander S, Weerakkody R, Sanguansri L, Gantenbein-Demarchi C, Augustin MA. Microencapsulated Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in whey protein and resistant starch matrices: Probiotic survival in fruit juice. J. Funct. Foods. 2013;5:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2012.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu F. Composition, structure, physicochemical properties, and modifications of cassava starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;122:456–480. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Q, Liu X, Zhao J, Tian F, Zhang HP, Zhang H, Chen W. Microencapsulation of Bifidobacterium bifidum F-35 in whey protein-based microcapsules by transglutaminase-induced gelation. J. Food Sci. 2012;77:270–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2012.02673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]