Watch a video presentation of this article

Abbreviations

- Ab

antibody

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- NHS

National Health Service

- PHE

Public Health England

- PPE

personal protective equipment

Background

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a bloodborne viral infection of the liver that, if untreated, can cause cirrhosis, liver failure, and liver cancer. In 2019, Public Health England (PHE) estimated that 89,000 people are chronically infected with HCV in England, with many drawn from marginalized and underserved groups in society, such as people experiencing homelessness. 1

In response to the global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, national restrictions on movement and social distancing were introduced in March 2020 and eased in July. During this time, there was disruption to many healthcare services, including testing and treating for bloodborne viruses, such as HCV. However, some English HCV care providers and allied stakeholders seized the opportunity to access homeless populations who were temporarily housed following government instruction 2 and so were less geographically dispersed and potentially more stable

This article provides an evaluation of these test and treat HCV interventions for homeless people while they were being housed during the pandemic in England (excluding London, for which a separate evaluation has been undertaken 3 ) to share the learning and inform future initiatives.

Methods

Interventions conducted in England (outside London) between March and September 2020 were evaluated using the following three methodological approaches:

A survey sent to all Hepatitis C Trust peer support leads in July 2020 to ask about outreach HCV testing and treatment in their region over the past month (Hepatitis C Trust peer support leads run a network of peer supporters that deliver HCV messages about the importance of testing and treatment to vulnerable individuals in the community.)

Enhanced monitoring data collected by HCV test and treat providers

Qualitative data collected through structured telephone conversations with providers of the homeless HCV test and treat interventions (henceforth referred to as “providers”)

Results

All of the 16 regions (outside London) that were sent the peer support leads survey reported doing outreach work with the homeless population during the past month.

Monitoring data were received from providers working in seven regions and covering interventions in 63 different settings (mainly hostels and hotels) (Fig. 1). However, due to the ongoing nature of the interventions, the completeness and quality of the data were limited.

FIG 1.

Mobile unit used in HCV testing event with homeless people in the car park of a hotel in Leeds, England, where they were being temporarily housed. Photo used with permission from Diane Williams, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust.

In the 32 residential settings where an estimate of the number housed was available, 1175 homeless people were thought to be housed at the time of the interventions, and 747 of these people were tested for HCV antibody (Ab), giving an uptake rate of 63.6%.

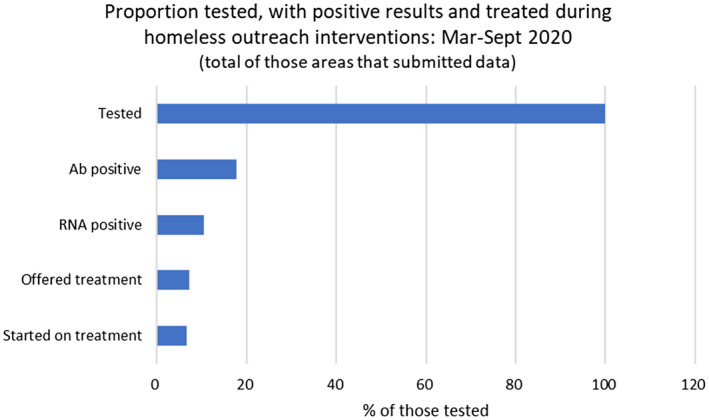

Cascade of care information for the homeless interventions is shown in Fig. 2. Across all 63 settings, a total of 1263 homeless clients were tested, with 224 found to be HCV Ab positive (17.7%). Of these, 133 (10.5% of those tested) were HCV RNA positive, indicating current infection. This is a very similar prevalence rate to that found in cross‐sectional survey testing of London homeless hostel residents in 2011 to 2013, where 13% were Ab positive and 10.4% were RNA positive. 4

FIG 2.

Proportion of homeless clients tested, with positive results, and treated, March to September 2020.

Overall, of the 1263 clients tested, 92 (69.2% of those testing RNA positive) had been offered treatment and 83 (90.2% of those offered) had started on treatment. However, due to the ongoing nature of the interventions, some settings had not yet initiated treatment at the time of analysis, and very few had had sufficient time to provide data on treatment completion or sustained virological response.

The findings from the 15 structured conversations with intervention providers are summarized under the framework of structure, process, and outcomes (Table 1). Key themes include the benefits of partnership working and of appropriate promotional materials, mixed views on the value of incentives, and the importance of speed from HCV test to treatment for this type of outreach work.

TABLE 1.

Findings From Conversations With Intervention Providers: Presented as Themes Under the Framework of Structure, Process, and Outcomes

| Framework | Aspect | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Bureaucracy | There were conflicting views on the impact of COVID‐19 on the bureaucracy of conducting test and treat interventions; some reported that it was more challenging because of increased restrictions, while others said that they had more freedom and flexibility than normal. |

| Settings | Some providers reported difficulty in engaging with hotel staff and obtaining their consent for testing events to take place on‐site, particularly for clinical procedures such as taking blood. | |

| Raising awareness of HCV and reducing associated stigma were highlighted as important for gaining engagement from hotel staff. | ||

| The spaces used to conduct testing varied considerably from gazebos in hotel car parks to individual bedrooms. In some cases, a testing van was used, and this was felt to be advantageous because it was versatile, fit for purpose, and, if unmarked, did not contribute to stigmatization. | ||

| Partnership working | Partnership working, particularly with peer supporters and local authority housing teams, was considered by providers as hugely valuable. | |

| Process | Promotional activities | Most providers reported using some sort of promotional materials (such as posters or fliers) to advertise the testing events. To destigmatize there were certain key messages that should be included, such as the different routes of HCV transmission (i.e., not just injecting drugs) and how easy and effective treatment is now. |

| Incentives | There were conflicting views among providers about the use of incentives. Some felt that they increased engagement and that clients would encourage others to come along because of the incentives on offer. Others felt that, although incentives might increase the numbers getting tested, clients need to be self‐motivated to complete treatment. | |

| Testing and treatment | A variety of different testing methods was used, but many providers mentioned that oral swabs and Dried Blood Spot were preferable to venous testing because some clients with a history of injecting drug use might feel embarrassed or stigmatized by their vein health. | |

| Speed of test to treatment was also felt to be important, so the use of rapid point‐of‐care test machines was considered to be very beneficial in keeping clients engaged. | ||

| Treatment was provided through the standard NHS route. | ||

| Because genotyping causes a delay in treatment initiation, providers were temporarily prioritizing pan‐genotypic drugs for the homeless clients reached through these interventions. | ||

| Most providers were giving clients the full course of medication at treatment initiation because this made it easier to comply with COVID‐19 restrictions and because of the risk of losing contact as clients were regularly moved between temporary accommodations. | ||

| In most areas, ongoing engagement with clients during their treatment was mainly being done by the peer supporters. | ||

| COVID‐19 precautions | Several providers conducted a COVID‐19 risk assessment, including checking for outbreaks or symptoms of COVID‐19 among the clients, and some had a written protocol on COVID‐19. | |

| Providers were generally confident that appropriate precautions for themselves and other partners had been taken (including PPE). However, many mentioned that clients did not maintain social distancing even when the layout of the setting had been specifically altered to facilitate this. Solutions to this included seeing just one client at a time by having them wait in their rooms until called, or providing clients with oral swabs that they could do without leaving their rooms. | ||

| Outcomes | Feedback from clients | Providers felt clients were happy to engage with the testing and often seemed relived by, and sometimes proud of, a negative result. In fact, some clients asked for a record of the result because this was part of their treatment recovery plan and demonstrated their abstinence from risky behaviors. |

| Some providers felt that COVID‐19, with the associated lockdown and temporary housing, had given their clients time to reflect and reengage with their own health. | ||

| Some negative feedback from clients was also reported; this included clients feeling targeted and stigmatized by promotional materials. | ||

| Other outcomes | In many settings, additional health and well‐being interventions (such as screening for other diseases, smoking cessation advice, and health checks) were carried out at the same time as the HCV testing. | |

| In some areas, providers felt conducting the interventions raised awareness of HCV among partner organizations, which may lead to other collaborations in the future and also gave an opportunity to recruit new peer supporters. |

Discussion

This evaluation has revealed that, despite national restrictions on movement and social engagements, and resultant severe service disruption, HCV test and treat interventions with the temporarily housed homeless population in England were widespread during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Across the seven regions that submitted data, 1263 homeless clients were tested, resulting in 83 clients starting on treatment. In addition, the interventions provided an opportunity for raising awareness of HCV and reducing stigma among partner organizations and homeless clients, which may lead to new collaborations and initiatives in the future.

Important barriers and enablers to carrying out HCV test and treat homeless interventions during a global pandemic have been identified. For instance, resistance from partner organizations, particularly hotel staff, was a major obstacle.

Structural enablers included having collaborations in place to expediate interventions and having existing resources, such as risk assessments and protocols, which could be quickly adapted.

Working with peer supporters appears to be a key process enabler, whereas the impact of incentives is less certain. Rapid testing and treatment initiation are important and can be achieved through use of a rapid point‐of‐care 5 machine and pan‐genotypic drugs.

Various enablers to sustaining engagement with treatment have been found; these include providing mobile phones to clients and linking with key workers.

On the basis of this evaluation, the following recommendations were made for future HCV testing and treating of homeless populations in a pandemic situation:

-

‐

Build strong partnerships to improve access to this client group and provide vital local intelligence.

-

‐

Promote testing interventions using appropriate content and language to avoid stigma.

-

‐

Evaluate use of incentives.

-

‐

Adopt a flexible, client‐focused approach to the practical arrangements for testing and ideally use oral swabs or Dried Blood Spot combined with rapid point‐of‐care testing.

-

‐

Find ways to initiate treatment outside of a clinical setting.

-

‐

Use innovative ways to keep in contact with and follow up with homeless clients.

-

‐

Ensure a risk assessment is done and pandemic precautions are implemented.

-

‐

Adopt a whole health approach, such as screening for other diseases at the same time.

-

‐

Carry out monitoring and evaluation of the interventions.

A limitation of this evaluation was the quality and completeness of available data from ongoing, “live” testing and treatment initiatives. In addition, analysis of outcomes would have been improved by consulting directly with the homeless clients to understand their experiences of the interventions.

It was important to produce the evaluation in a timely fashion so lessons learned could inform the ongoing COVID‐19 response. However, this meant that some areas were yet to start clients on treatment, and very few were able to report treatment outcomes.

Conclusions

This evaluation provides further evidence of the high prevalence of HCV in homeless populations. It also shows how the initiative and resourcefulness of HCV care providers in England resulted in levels of HCV diagnosis (with 10.5% having active infection) and rates of treatment initiation (90.2% among those offered) that would not otherwise have been achieved during the COVID‐19 pandemic. These interventions have contributed to the HCV elimination goal at a time when transmission risk was likely to be very high among this vulnerable group because of service disruptions and an increase in risk‐taking behaviors. Furthermore, the innovative strategies used in these interventions can be sustained after the pandemic to assure this marginalized population benefits from national HCV elimination.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Public Health England . Hepatitis C in England 2020: working to eliminate hepatitis C as a major public health threat. London: Public Health England; 2020. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/943154/HCV_in_the_UK_2020.pdf. Accessed September 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government . Letter from Minister Hall to local authorities on plans to protect rough sleepers. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/876466/Letter_from_Minister_Hall_to_Local_Authorities.pdf. Published March 16, 2020. Accessed September 21, 2020.

- 3. London Joint Working Group on Substance Use and Hepatitis C . Hepatitis C testing and treatment interventions for the homeless population in London during the Covid‐19 pandemic. Outcomes and learning. Available at: http://ljwg.org.uk/london‐comes‐together‐to‐treat‐hepatitis‐c‐during‐lockdown/. Published 2020. Accessed January 6, 2021.

- 4. Aldridge RW, Hayward AC, Hemming S, et al. High prevalence of latent tuberculosis and bloodborne virus infection in a homeless population. Thorax 2018;73:557‐564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cepheid . Hepatitis C (HCV) molecular test: Xpert HCV VL Fingerstick. Available at: https://www.Cepheid.com/en/tests/Virology/Xpert‐HCV‐VL‐Fingerstick. Accessed October 2, 2020.