Abstract

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) exposure may increase adiposity and obesity risk in children. However, no studies have extended these findings into adolescence or identified periods of heightened susceptibility. We estimated associations of repeated pre- and postnatal serum PFAS concentrations with adolescent adiposity and risk of overweight/obesity. We studied 212 mother–offspring pairs from the HOME Study. We quantified serum concentrations of four PFAS in mothers at ~16 week gestation and their children at birth and ages 3, 8, and 12 years. We assessed adiposity at 12 years using anthropometry and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Using multiple informant models, we estimated covariate-adjusted associations of an interquartile range (IQR) increase in log2-transformed PFAS for each time period with adiposity measures and tested differences in these associations. Serum perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS) concentrations during pregnancy were associated with modest increases in central adiposity and risk of overweight/obesity, but there was no consistent pattern for postnatal concentrations. We observed nonlinear associations between PFOA in pregnancy and some measures of adiposity. Overall, we observed a pattern of modest positive associations of gestational PFOA and PFHxS concentrations with central adiposity and the risk of obesity in adolescents, while no pattern was observed for postnatal PFAS concentrations.

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a diverse group of fluorinated chemicals, which have been widely used in industry and consumer products since the 1950s because of their high thermal and chemical stability, hydrophobicity, and lipophobicity.1 PFAS have been used in some food packaging materials, nonstick cookware, fire-fighting foams, waxes, furniture, and pesticides.1,2 The production of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) was discontinued or reduced in the United States due to a set of voluntary phase-outs beginning in the 2000s.1,3 However, PFOA, PFOS, perfluorononanoate (PFNA), and perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS) are still detectable in the serum of nearly all American children and adults.4,5 The major routes of human PFAS exposure include consumption of contaminated food and drinking water, as well as inhalation of indoor air and consumption/inhalation of house dust.2,5 At least 19 million Americans are exposed to PFAS via drinking water,6 highlighting the need to improve our understanding of the impact of PFAS on human health, especially in susceptible populations such as children and pregnant women.

Prenatal exposure to PFAS has been associated with preterm birth,7 decreased birth weight,8 and altered child growth9,10 in humans. However, epidemiological studies report mixed findings about the association between early life PFAS exposure and adiposity in children or adults.11,12 Prenatal exposure to PFAS has been positively associated with adiposity in early to mid-childhood13–17 and adulthood,18 while other studies found inverse19 or null associations.20,21 Two prospective studies reported that postnatal serum PFAS concentrations were positively associated with adiposity in preschoolers,22 adolescents, and young adults;23 however, one study reported null associations.24 Cross-sectional studies have reported inconsistent findings.25–29

To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the associations between PFAS exposure and adolescent adiposity or identified potential periods of heightened susceptibility during gestation or childhood. Moreover, the majority of published studies used indirect measurements of adiposity, such as weight, body mass index (BMI), and waist circumference, with few studies using direct measures (e.g., dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA)).17,20,25,27 Therefore, we estimated the associations of five repeated pre- and postnatal serum PFAS concentrations collected during gestation and the first 12 years of life with detailed measures of adolescent adiposity to evaluate periods of heightened susceptibility to the potential obesogenic effects of PFAS exposure.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Participants.

We used data from the Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment (HOME) Study, an ongoing pregnancy and birth cohort that recruited pregnant women from nine prenatal clinics affiliated with three hospitals in the Cincinnati, Ohio metropolitan area between March 2003 and January 2006. Pregnant women in the HOME Study had median PFOA concentrations 2 times higher than pregnant women in the general population in the United States. This is possibly because their drinking water was contaminated with PFOA released by DuPont Washington Works plant in Parkersburg, West Virginia. Details of eligibility criteria and recruitment methods have been published previously.30 A total of 468 pregnant women in their first or second trimester enrolled. We conducted longitudinal follow-up among offspring at age 4 weeks and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, and 12 years.

Among 423 participants eligible for follow-up at age ~12 years (range: 11–14 years), we excluded children who were twins (n = 22) and had congenital anomalies (n = 5). Additional details regarding participant characteristics, follow-up, and study measures at the 12 year visit are described elsewhere.31 Among the remaining 396 children, we only included participants who had at least one serum PFAS measure prenatally or in childhood at age 3, 8, or 12 years (n = 389). Of these, 212 children who had at least one measurement of anthropometry or dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and complete information on covariates were included in the final analytic sample.

The research protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) and the participating delivery hospitals prior to enrollment. Brown University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) IRBs deferred to the IRB from CCHMC. Written informed consent was obtained from mothers at each study visit, and written informed assent was obtained from children at age 12 years.

2.2. PFAS Exposure Assessment.

To assess prenatal PFAS exposure, we quantified serum concentrations of PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, and PFHxS in mothers at ~16 or 26 week gestation or within 48 h of delivery. Given that blood volume may change during pregnancy, we measured PFAS concentrations in the 16 week serum if available (88%). For mothers who did not have 16 week PFAS concentrations due to insufficient volume, we used the 26 week (8%) or delivery sample (4%). For postnatal PFAS exposure assessment, we quantified serum concentrations of these same four PFAS in children at birth (venous cord blood) and ages 3, 8, and 12 years. All serum PFAS concentrations were measured using online solid-phase extraction coupled to high-performance liquid chromatography-isotope dilution tandem mass spectrometry at CDC.32 The limit of detection (LOD) was 0.1 ng/ mL for PFOA, PFNA, and PFHxS and 0.2 ng/mL for PFOS. PFAS were detectable in approximately 98% of serum samples, and we replaced concentrations below LOD with LOD/√2. We summed the concentrations of both linear and branched isomers to obtain the total concentrations of PFOS and PFOA, respectively. Additional information on the quality control tests have been described elsewhere.33

2.3. Anthropometry and DXA.

When adolescents were on average 12.1 years old, trained staff measured weight, height, and waist and hip circumferences in triplicate following standardized protocols to the nearest 0.01 kg, 0.1 cm, and 0.1 cm, respectively.31 Children wore hospital scrubs and had their shoes and head covering off during anthropometric assessments. We calculated body mass index (BMI) in kg/m2 from weight and height and obtained age- and sex-specific BMI z-scores based on the CDC growth curve.34 Childhood overweight was defined as BMI z-scores >1, and obesity as BMI z-score >2.

At the same visit, trained technicians measured children’s total and regional fat mass by a whole-body DXA scan with a Hologic Horizon densitometer (model A; Hologic Inc., Marlborough, MA). Percentage regional fat measures were calculated for the trunk, android, and gynoid subregions as the regional fat mass divided by the whole-body fat mass × 100. The whole-body DXA scan also yielded a measure of visceral fat area (cm2), which is highly correlated with visceral fat area estimated by computed tomography.35 A spine phantom was scanned daily to ensure optimal machine performance and calibration as recommended by the manufacturer. Age- and sex-specific fat mass index (fat mass/height2, kg/m2) z-scores were calculated based on the reference values generated using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004.36 We applied thresholds of >1 and >2 standard deviation (SD) to define overweight and obesity, respectively, using fat mass index z-scores.

2.4. Covariates.

We selected a set of potential confounders that may be associated with both PFAS concentrations and adolescent adiposity using directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) and based on prior knowledge37,38 (Figures S1 and S2). Trained research staff collected sociodemographic covariates using standardized computer-assisted interviews, including maternal age, race, marital status, and education in the second or third trimester. We collected data on prepregnancy weight and height and parity from medical records. We used standardized interviewer-administered surveys to assess breastfeeding duration.39 We measured serum concentrations of cotinine, a biomarker of tobacco smoke exposure, using high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.40 Puberty was evaluated using the Tanner stage based on pubic hair development in both sexes at the 12 year study visit using a self-report instrument. For pubic hair growth, stage 1 indicates prepubertal showing no sexual hair at all. Stage 2 indicates the onset of puberty showing sparse growth of long and downy hair with slight pigmentation. At stages 3 and 4, the pubic hair becomes darker and coarser and reaches adult levels at stage 5.41 In the sensitivity analyses, we also considered adjusting for several additional variables, including birth weight and pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders, which were assessed using medical records. We also evaluated adolescent physical activity using a validated self-report questionnaire.42 To assess adolescent diet quality, we calculated 2015 Health Eating Index scores using data from three 24 h dietary recalls.43

2.5. Statistical Analyses.

We described the univariate characteristics of each PFAS, adiposity measures, and covariates (mean ± standard deviations [SD] or proportions [%]). We also calculated the mean ± SD of total body fat percentage according to the categories of each covariate.

We log2-transformed PFAS concentrations prior to analysis to reduce the potential influence of outliers. We calculated Spearman correlation coefficients between log2-transformed PFAS at each time point. In addition, we examined the potential nonlinear association between PFAS concentrations and measures of adiposity at age 12 years using covariate-adjusted natural cubic splines and testing the statistical significance of the spline terms.

We used multiple informant models to estimate covariate-adjusted differences in each adiposity measure with an interquartile range (IQR) increase in log2-transformed concentrations of the four PFAS (βs and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) at the five different time points. Moreover, we used these models to statistically test the difference in the PFAS-adiposity association at each time point. Multiple informant models jointly estimate a set of separate multiple regressions, using generalized estimating equations for the parameter estimation, and provide a formal test on the difference in the strength of the associations between PFAS concentrations and adiposity measures across five time points.44 Finally, since some previous studies reported sex-specific associations between PFAS and adiposity,17,18,26,28 we examined the potential modifying effects by child sex using a three-way interaction term of child sex, serum PFAS concentration, and timing of exposure assessment. All models were adjusted for maternal age, race, marital status, education, parity, serum cotinine concentrations, prepregnancy BMI, breastfeeding duration (postnatal PFAS concentrations only), and child age, sex, and pubic hair stage.

We performed all these analyses using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R version 3.2.3 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

2.6. Secondary and Sensitivity Analyses.

We estimated the risk of adolescent overweight or obesity in relation to PFAS concentrations using modified Poisson regression with robust standard errors. Because hypertension is associated with an increased risk of impaired kidney function, which confounds the association between prenatal PFAS and fetal growth,45,46 we adjusted for the presence of pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders. In addition, because prior studies reported associations of low birth weight with pediatric obesity,47 we repeated our analyses by adjusting for sex-specific birth weight for gestational age z-scores.48 Finally, we also adjusted for adolescent physical activity levels and diet quality using a summary physical activity and Health Eating Index score, respectively.

3. RESULTS

The mean age of the 212 children included in this analysis was 12.4 years (SD: 0.7), 55% were girls, and 90% were stage 2+ for pubic hair development (Table 1). Mothers in our study sample were predominately non-Hispanic white (59%), married (63%), and had at least one previous pregnancy (58%). The percentage of mothers with a high school degree or less was about 23%. On average, mothers were age 29.4 (SD: 6.0) years at delivery. Adolescents whose mothers were obese before pregnancy had a higher body fat percentage at age 12. Body fat percentages did not differ substantially according to categories of other covariates. Thirty-four percent of these children were overweight or obese (Table 2). Generally, girls had higher adiposity than boys at age 12 years.

Table 1.

Adolescent Body Fat Percent at 12 Years of Age According to Covariates: The HOME Study (Total N = 212)

| characteristics | N (%) | body fat percent (%)a mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| maternal characteristics | ||

| race/ethnicity | ||

| white, non-Hispanic | 125 (59.0) | 32.3 (6.3) |

| black, non-Hispanic | 74 (34.9) | 31.7 (7.0) |

| all others | 13 (6.1) | 31.5 (7.2) |

| education | ||

| high school or less | 49 (23.1) | 32.4 (7.6) |

| tech school/some | 60 (28.3) | 31.5 (6.3) |

| college | ||

| bachelor’s or more | 103 (48.6) | 32.1 (6.3) |

| maternal age (years) | ||

| 18–25 | 52 (24.5) | 31.1 (7.1) |

| >25–35 | 128 (60.4) | 32.2 (5.9) |

| >35 | 32 (15.1) | 32.9 (8.1) |

| marital status | ||

| Yes | 134 (63.2) | 32.1 (6.4) |

| No | 78 (36.8) | 31.9 (7.0) |

| parity | ||

| 0 | 90 (42.4) | 32.1 (6.4) |

| 1 | 69 (32.6) | 31.4 (6.3) |

| 2+ | 53 (25.0) | 32.6 (7.3) |

| serum cotinine (ng/mL) | ||

| <0.015 | 40 (18.9) | 32.5 (6.4) |

| 0.015-<3 | 152 (71.7) | 32.0 (6.7) |

| ≥3 | 20 (9.4) | 31.0 (6.0) |

| prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| underweight/normal (<24.9) | 113 (53.3) | 31.0 (6.0) |

| overweight (25.0–29.9) | 55 (25.9) | 32.5 (6.6) |

| obese (≥30) | 44 (20.8) | 34.0 (7.6) |

| child characteristics | ||

| sex | ||

| females | 116 (54.7) | 34.0 (6.1) |

| males | 96 (45.3) | 29.6 (6.3) |

| breastfeeding duration (months) | ||

| <6 | 119 (56.1) | 31.8 (7.0) |

| ≥6 | 93 (43.9) | 32.2 (6.0) |

| pubic hair stage | ||

| 1 | 22 (10.4) | 31.3 (6.8) |

| 2 | 55 (25.9) | 32.3 (6.4) |

| 3 | 65 (30.7) | 32.2 (6.5) |

| 4 | 43 (20.3) | 32.0 (6.8) |

| 5 | 27 (12.7) | 31.4 (7.0) |

Body fat percent = total body fat mass (g) × 100/total body mass (g).

Table 2.

Distribution of Adolescent Measures of Overall and Regional Adiposity at Age 12 Years: The HOME Study

| variable | total N | overall mean (SD) or N [%] | N | boys mean (SD) or N [%] | N | girls mean (SD) or N [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| overall adiposity | ||||||

| normal/underweight | 141 [66.5] | 71 [74.0] | 70 [60.3] | |||

| overweight (>1 SD) | 61 [28.8] | 23 [24.9] | 38 [32.8] | |||

| obese (>2 SD) | 10 [4.7] | 2 [2.1] | 8 [6.9] | |||

| BMI z-score | 212 | 0.3 (1.1) | 96 | 0.1 (1.2) | 116 | 0.5 (1.1) |

| fat mass index z-score | 206 | 0.2 (0.8) | 93 | 0.2 (0.7) | 113 | 0.2 (0.9) |

| body fat percent (%) | 206 | 32.0 (6.6) | 93 | 29.6 (6.3) | 113 | 34.0 (6.1) |

| central and gynoid adiposity | ||||||

| waist circumference (cm) | 212 | 72.2 (12.3) | 96 | 69.5 (10.4) | 116 | 74.4 (13.4) |

| hip circumference (cm) | 212 | 84.5 (11.0) | 96 | 81.3 (9.7) | 116 | 87.0 (11.4) |

| waist-to-hip ratio | 212 | 0.9 (0.06) | 96 | 0.9 (0.06) | 116 | 0.9 (0.06) |

| visceral fat area (cm2) | 206 | 44.6 (20.2) | 93 | 50.5 (13.9) | 113 | 39.8 (23.2) |

| trunk fat percent (%)a | 206 | 36.3 (4.0) | 93 | 35.3 (3.5) | 113 | 37.2 (4.2) |

| android fat percent (%)a | 206 | 5.2 (1.0) | 93 | 5.1 (0.9) | 113 | 5.4 (1.1) |

| gynoid fat percent (%)a | 206 | 17.0 (1.6) | 93 | 16.4 (1.4) | 113 | 17.4 (1.6) |

| android/gynoid fat percent ratio | 206 | 0.3 (0.07) | 93 | 0.3 (0.06) | 113 | 0.3 (0.08) |

Percentage of regional fat mass to total body fat mass. Fat mass index = total body fat mass (kg)/(height × height (m2)).

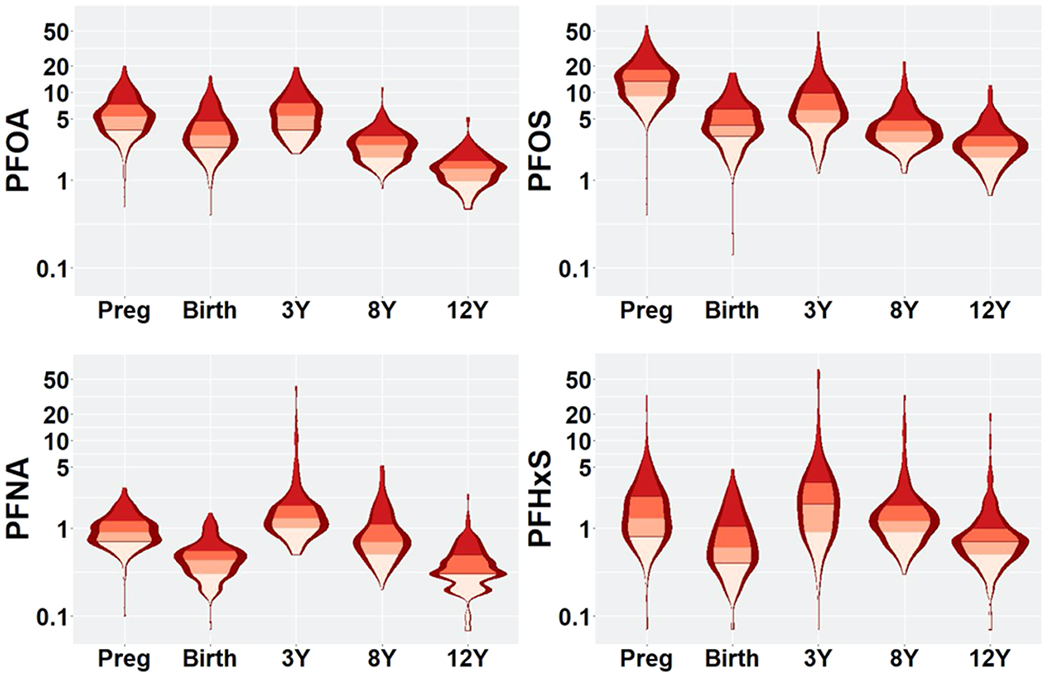

Median serum concentrations of PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, and PFHxS in pregnancy were 5.3, 13.3, 0.9, and 1.3 ng/mL, respectively (Figure 1 and Table S1). Median maternal serum PFAS concentrations during pregnancy were higher than median concentrations in infants at delivery. When comparing PFAS concentrations across childhood, 3 year PFAS concentrations were the highest. PFAS concentrations did not differ by child sex (Table S1). Serum PFAS concentrations were weakly to moderately correlated with each other in pregnancy (ρ = 0.33–0.60), cord blood (ρ = 0.22–0.59), at age 3 (ρ = 0.26–0.72), at age 8 (ρ = 0.19–0.61), and at age 12 (ρ = 0.39–0.68) (Figure S3A). Overall, for each PFAS, prenatal concentrations were weakly correlated with postnatal concentrations (Figure S3B).

Figure 1.

Violin plots of serum log2-transformed PFAS concentrations (ng/mL) from pregnancy to age 12 years: the HOME Study. Preg: pregnancy; PFOS: perfluorooctane sulfonate; PFOA, perfluorooctanoate; PFNA: perfluorononanoate; and PFHxS: perfluorohexane sulfonate.

Figure 2 shows the associations of prenatal and postnatal PFAS concentrations with central adiposity measures assessed via anthropometry (Figure 2A) and DXA (Figure 2B), as well as overall adiposity (Figure 2C) at age 12 years. After adjusting for covariates, serum PFOA and PFHxS concentrations during pregnancy were consistently associated with higher levels of central adiposity across all measures but lower levels of gynoid fat percent (Figure 2A,B and Table S2). For instance, each interquartile range increase in log2-transformed prenatal PFOA concentration was associated with higher waist-to-hip ratio (β = 0.02, 95%CI: 0.00, 0.03), waist circumference (β = 2.0 cm, 95%CI: −0.8, 4.8), visceral fat area (β = 1.4 cm2, 95%CI: −2.9, 5.7), trunk fat percent (0.4%, 95%CI: −0.5, 1.4), and android fat percent (β = 0.2%, 95%CI: −0.1, 0.4) but lower gynoid fat percent (β = −0.2%, 95%CI: −0.6, 0.3). There was no pattern of associations between other PFAS during pregnancy and measures of adiposity in these adolescents (Figure 2 and Table S2). Moreover, childhood PFAS concentrations were generally not associated with measures of overall or regional adiposity. Our results suggest that the associations with adiposity potentially differ by exposure periods, although the interaction terms did not reach statistical significance (PFAS × visit interaction p-values ≥0.2) (Table S2). In addition, we observed a pattern of positive associations of serum PFHxS concentrations with all measures of overall adiposity (Figure 2C and Table S2).

Figure 2.

Adjusted associations (β [95% CI]) of 1-interquartile range (IQR) increase in log2-transformed PFAS concentrations with measures of overall and regional adiposity at 12 years: the HOME Study. Preg: pregnancy; PFOS: perfluorooctane sulfonate; PFOA, perfluorooctanoate; PFNA: perfluorononanoate; PFHxS: perfluorohexane sulfonate; percentage of regional fat mass to total body fat mass. Adjusted for a visit, the interaction between visit and PFAS, maternal age, race, marital status and education, parity, maternal smoking, prepregnancy BMI, and child age, sex, and puberty. Y-axis shows β and 95% confidence interval; X-axis shows the different visits across time points.

We observed evidence suggesting potential nonlinear associations between prenatal PFOA and some measures of adiposity, with nonlinearity p-values ranging from 0.03 to 0.05 for BMI z-score, fat mass index z-score, waist circumference, hip circumference, and visceral fat area (Figure 3). Adjusted mean adiposity measures were positively associated with prenatal PFOA up to the median PFOA concentration and then slightly declined or plateaued at higher concentrations. Figure S4 shows the adjusted natural cubic splines of the associations of all PFAS concentrations during pregnancy with overall (Figure S4A) and central adiposity using anthropometry (Figure S4B) and DXA (Figure S4C,D) at age 12 years. We found that the associations between other PFAS (i.e., PFOS, PFNA, and PFHxS) and adiposity appeared to be linear (nonlinearity p-values >0.05) (Figure S4).

Figure 3.

Adjusted natural cubic splines of the associations of log2-transformed perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) concentrations during pregnancy with adiposity measures at age 12 years in adolescents from the HOME Study. Adjusted for maternal age, race, marital status and education, parity, maternal smoking, breastfeeding duration (postnatal concentrations only), prepregnancy BMI, and child age, sex, and puberty.

When stratifying by child sex, we found that PFOA and PFHxS concentrations during pregnancy were consistently associated with higher overall and central adiposity across all measures in girls, while no consistent associations were found in boys (Table S3 and Figure S5). However, the three-way interaction terms between PFAS, the timing of the PFAS exposure assessment, and child sex were not significant (p-interaction >0.2) (Table S3).

In secondary analyses, we observed positive associations between prenatal exposure to all four PFAS during pregnancy and the risk of being overweight or obese at age 12; these associations were modestly stronger when using the fat mass index z-score to define overweight or obesity (Table 3). For instance, each IQR increase in prenatal PFAS concentrations was associated with 70% increased risk of childhood overweight or obesity (PFOA: β = 1.7, 95%CI: 0.9, 3.1; PFHxS: β = 1.7, 95%CI: 1.1, 2.7).

Table 3.

Adjusted Relative Risk of Overweight/Obesity with 1-Interquartile Range (IQR) Increase in Log2-Transformed PFAS Concentrations during Pregnancya

| overweight/obesity defined by BMI-z |

overweight/obesity defined by FMI-z |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFAS | crude RR (95%CI) | adjusted RR (95%CI) | crude RR (95%CI) | adjusted RR (95%CI) |

| PFOA | 1.30 (0.90, 1.87) | 1.37 (0.92, 2.03) | 1.53 (0.89, 2.63) | 1.66 (0.90, 3.07) |

| PFOS | 0.94 (0.64, 1.37) | 1.11 (0.76, 1.63) | 1.26 (0.69, 2.32) | 1.51 (0.81, 2.85) |

| PFNA | 1.01 (0.66, 1.54) | 1.14 (0.74, 1.75) | 1.17 (0.68, 2.01) | 1.19 (0.67, 2.13) |

| PFHxS | 1.07 (0.82, 1.41) | 1.23 (0.93, 1.63) | 1.40 (0.94, 2.08) | 1.71 (1.08, 2.73) |

PFOS: perfluorooctane sulfonate; PFOA, perfluorooctanoate; PFNA: perfluorononanoate; PFHxS: perfluorohexane sulfonate. Fat mass index = total body fat mass (kg)/(height × height (m2)). Adjusted for maternal age, race, marital status and education, parity, maternal smoking, prepregnancy BMI, and child age, sex, and puberty.

In sensitivity analyses, we adjusted for physical activity level scores, healthy eating index scores, birth weight for gestational age z-scores, and pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders. However, these adjustments did not meaningfully change the associations of prenatal PFAS concentrations with adolescent adiposity measures, and in some cases strengthened the associations (Table S4). When mutually adjusting for all prenatal PFAS concentrations in the same model, the associations with PFOA and PFHxS were strengthened, but the association with PFOS became negative (Table S5).

4. DISCUSSION

In these mother–adolescent pairs from the HOME Study, we observed a pattern of modest positive associations of prenatal serum concentrations of PFOA and PFHxS during pregnancy with greater central body fat, as well as the risk of being overweight or obese at age 12. However, there was no clear pattern for postnatal PFAS concentrations. We observed evidence suggesting that prenatal PFOA was nonlinearly associated with some adiposity measures and more strongly associated with greater adiposity in girls than in boys. These results were robust to additional adjustment for physical activity, diet, birth weight, and pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders.

Prenatal concentrations of PFOS, PFNA, and PFHxS in the HOME Study were similar to those of pregnant women in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2008,49 whereas the median PFOA concentrations (5.3 vs 2.2 ng/mL) during pregnancy were higher. We speculate that elevated serum PFOA concentrations in HOME Study women could be caused by exposure to drinking water contaminated by PFOA emitted from the Parkersburg DuPont Washington Works plant.15

We found that increasing prenatal PFOA and PFHxS concentrations were associated with greater central adiposity in adolescence although the 95% CIs of our estimates included the null value. Our results are consistent with some prior studies in children or young adults,13–18 although the majority of these studies used indirect measures of adiposity and did not assess body fat distribution. Specifically, three prospective cohort studies reported that prenatal PFAS concentrations were positively associated with BMI among 200 children at age 3–5 years from Sweden,13 body fat percent and waist circumference in 204 HOME Study children at age 8 years,15 and waist circumference and skinfold thickness in 870 children at age 6–10 years from the Greater Boston area.17 In addition, maternal concentrations of PFAS during pregnancy were associated with increased risk of being overweight/obese in 412 Norwegian and Swedish children at age 5 years,14 1022 Ukraine children at age 5–9 years,16 and 665 young adults at age 20 years from Denmark.18 In contrast, a Danish birth cohort reported inverse associations between maternal PFAS during pregnancy and BMI at age 7 years (n = 519).19 Two prospective studies reported no clear associations.20,21

Inconsistencies across prior studies may relate to the differences in the study designs, concentrations of PFAS, or the timing and method of adiposity measurements. For instance, Andersen et al.19 used self- or parent-reported weight and height, which could contribute to the misclassification of BMI and subsequently attenuate associations with PFAS.50,51 Moreover, prenatal PFAS concentrations were lower in Manzano-Salgado’s study21 than those reported in our study (e.g., median PFOA: 2.3 vs 5.3 ng/mL; PFHxS: 0.6 vs 1.3 mL). Hartman et al. included a subset of girls who were originally selected for a study on menarche and completed DXA assessments; therefore, their study may be subject to selection bias20.

We found no clear pattern in the associations of postnatal PFAS concentrations at age 3, 8, or 12 years with any measure of body fat distribution in children at age 12 years. Similar to our results, a prospective study of 8764 U.S. adults from a community with drinking water contaminated with PFOA found that early life serum PFOA concentrations (average concentrations at ages 1–3 years) were not associated with the risk of being overweight or obese.24 A cross-sectional study of 499 Danish children aged 8–10 years found that plasma concentrations of PFOA and PFOS were not associated with BMI, waist circumference, or skinfold thickness.29 Some prospective or cross-sectional studies report mixed associations between postnatal PFAS concentrations and childhood adiposity measures.22,23,25–28 Inconsistent findings among these studies could be attributed to the use of different study populations and design, inaccurate measurement of adiposity, or varying concentration ranges and timing of PFAS exposure assessment.

In this study, prenatal PFAS concentrations were overall weakly correlated with postnatal PFAS concentrations in our study. Thus, correlations among PFAS may not explain the lack of statistically significant results that identify the specific periods of heightened susceptibility. In addition, we found that some of the point estimates for postnatal PFAS concentration are negative, while their prenatal counterparts are positive. Therefore, even modest correlations are not solely responsible for our lack of statistically significant discernible periods of heightened susceptibility.

Our findings suggest that the developing fetus may be more susceptible to the influence of PFAS exposure on body composition, as compared with postnatal exposures. This is biologically plausible because PFAS can readily pass through the placenta and enter fetal circulation.52 In addition, late pregnancy may be a more sensitive period for exposures to perturb body fat development, as the fetus undergoes rapid fetal growth and fat deposition during the third trimester.53 Finally, given that fetal exposure to certain obesogens may alter the epigenome of stem cells, resulting in increased production of adipocytes later in life,14,54 it is possible that the development of obesity may be programmed as early as during gestation.

While the biological mechanisms underlying the PFAS-adiposity associations are not well established, a few potential pathways have been proposed to explain these associations. PFAS can activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α and γ (PPARα/γ), which can increase lipid metabolism and adipocyte differentiation to stimulate body fat storage.12,55 PFAS have been found to disrupt thyroid function and possibly cause hypothyroidism (i.e., decreasing total or free thyroxine [T4] and increasing thyroid stimulating hormone [TSH]), which can increase body fat.56–58 As endocrine-disrupting chemicals, PFAS may directly interact with estrogen receptors or decrease circulating estrogen concentrations,59,60 and women with low levels of estrogen may have greater visceral fat.61 Thus, the sex-specific associations of prenatal PFOA with childhood adiposity measures may be explained by the ability for PFAS to interact with gonadal hormone pathways related to adipose tissue development.

We found some evidence suggesting that prenatal PFOA and PFHxS concentrations were more strongly associated with adolescent adiposity than PFOS and PFNA The differential effects of PFAS could be due to the differences in their biological activity. For instance, it is possible that the activation of PPARα may be higher for PFOA than PFOS,62 and some studies argue that, unlike PFOA, the toxicity of PFOS may not depend on the activation of PPARα.63 Moreover, the placental transfer and postnatal offspring/maternal blood ratio was higher for PFOA than other PFAS, which could increase the burden of PFOA exposure in early life.64

There are some limitations of our study. First, we had a relatively modest sample size, especially for identifying distinct periods of heightened susceptibility and sex-specific associations. Given the movement away from null hypothesis testing and the fact that few of the observed statistically significant findings would not hold after adjusting for multiple comparisons, we emphasized the pattern of consistent associations across each measure of adiposity to interpret our results without relying on the statistical significance of these associations. In addition, we treated our sex-specific analyses as more exploratory in our secondary analyses given the lack of power to detect significant three-way interaction. Longitudinal studies with large samples are needed to improve our understanding of the sex-specific effects on adiposity. Second, it is possible that our results were limited by the potential residual confounding effects. For instance, we did not measure circulating albumin concentrations or glomerular filtration rate during pregnancy. However, prior studies found that adjusting for markers of pregnancy hemodynamics (i.e., glomerular filtration rate and plasma albumin) did not meaningfully alter effect estimates, suggesting that these markers may not confound the associations between PFAS and adiposity.7,17,65 A large number of studies have indicated that parental BMI may be a strong predictor of offspring adiposity highlighting the genetic component of obesity. However, we did not collect data on paternal body weight, and it seems unlikely that paternal weight could confound the associations between prenatal PFAS during pregnancy and offspring adiposity. Additionally, we did not adjust for maternal gestational weight gain (GWG) in this study because it may be a causal intermediate of the associations between prenatal PFAS and adiposity in children.17 Furthermore, it has been shown that the impact on offspring adiposity of GWG in addition to the impact of prepregnancy BMI is small.66

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. First, we assessed body fat composition and distribution using DXA, which provides detailed and accurate measurements of adiposity and reduces potential misclassification of adiposity. Second, we were able to account for several important confounders including prepregnancy BMI, maternal smoking, breastfeeding duration, and adolescent physical activity and diet. Third, we examined the associations of adolescent adiposity with five repeated measures of serum concentrations of PFAS that covered the periods of pregnancy, early and middle childhood, and adolescence. In addition, the use of multiple informant models enabled us to identify the potential periods of heightened susceptibility and reduce the number of fitted regression models.

In conclusion, we found that gestational, but not postnatal, serum concentrations of PFOA and PFHxS were consistently associated with subtle increases in measures of central body fat among HOME Study adolescents. Future studies could confirm these findings in other populations and identify potential biological pathways underlying these associations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to our participants for the time they have given to our study. This work was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grants P01 ES011261, R01 ES014575, R01 ES020349, R01 ES027224, and R01 ES025214.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.0c06088.

Distribution of serum concentrations of PFAS; adjusted associations of 1-IQR increase in log2-transformed PFAS concentrations; associations of PFAS during pregnancy; mutual adjustment of log2-transformed PFAS concentrations; DAG of potential confounders of the associations; heat map of Pearson correlation coefficients; adjusted natural cubic splines of the associations between child PFAS concentrations; and adjusted associations of 1-IQR increase in log2-transformed PFAS concentrations (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c06088

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Joseph M Braun (JMB) was financially compensated for serving as an expert witness for plaintiffs in litigation related to tobacco smoke exposures and received honoraria from Quest Diagnostic for serving on an expert panel related to endocrine disrupting chemicals. JMBs institution was financially compensated for his services as an expert witness for plaintiffs in litigation related to PFAS-contaminated drinking water; these funds were not paid to JMB directly. Karl T. Kelsey (KTK) is a founder and scientific advisor for Cellintec, which had no role in this work. All other authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. Government, or the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the CDC, the Public Health Service, or DHHS.

Contributor Information

Yun Liu, Department of Epidemiology, Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, Rhode Island 02903, United States.

Nan Li, Department of Epidemiology, Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, Rhode Island 02903, United States.

George D. Papandonatos, Department of Biostatistics, Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, Rhode Island 02903, United States

Antonia M. Calafat, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia 30329-4018, United States

Charles B. Eaton, Department of Epidemiology, Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, Rhode Island 02903, United States; Center for Primary Care and Prevention, Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, Pawtucket, Rhode Island 02860-4499, United States; Department of Family Medicine, Brown University School of Medicine, Providence, Rhode Island 02912, United States

Karl T. Kelsey, Department of Epidemiology, Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, Rhode Island 02903, United States

Aimin Chen, Department of Biostatics, Epidemiology & Informatics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104, United States.

Bruce P. Lanphear, Faculty of Health Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia V5A 1S6, Canada

Kim M. Cecil, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio 45229-3026, United States

Heidi J. Kalkwarf, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio 45229-3026, United States

Kimberly Yolton, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio 45229-3026, United States.

Joseph M. Braun, Department of Epidemiology, Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, Rhode Island 02903, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Buck RC; Franklin J; Berger U; Conder JM; Cousins IT; de Voogt P; Jensen AA; Kannan K; Mabury SA; van Leeuwen SP Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manage 2011, 7, 513–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).ATSDR. Toxicological Profile for Perfluoroalkyls; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service: Atlanta, GA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- (3).USEPA. Risk Management for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) under TSCA. https://www.epa.gov/assessing-and-managing-chemicals-under-tsca/risk-management-and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas.

- (4).CDC. Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals; Updated Tables, January 2019; CDC, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Ye X; Kato K; Wong LY; Jia T; Kalathil A; Latremouille J; Calafat AM Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in sera from children 3 to 11 years of age participating in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2014. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2018, 221, 9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Kuehn B PFAS Water Contamination Examined. JAMA 2019, 322, No. 1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sagiv SK; Rifas-Shiman SL; Fleisch AF; Webster TF; Calafat AM; Ye X; Gillman MW; Oken E Early-Pregnancy Plasma Concentrations of Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Birth Outcomes in Project Viva: Confounded by Pregnancy Hemodynamics? Am. J. Epidemiol 2018, 187, 793–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Johnson PI; Sutton P; Atchley DS; Koustas E; Lam J; Sen S; Robinson KA; Axelrad DA; Woodruff TJ The Navigation Guide - evidence-based medicine meets environmental health: systematic review of human evidence for PFOA effects on fetal growth. Environ. Health Perspect 2014, 122, 1028–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Shoaff J; Papandonatos GD; Calafat AM; Chen A; Lanphear BP; Ehrlich S; Kelsey KT; Braun JM Prenatal Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances: Infant Birth Weight and Early Life Growth. Environ. Epidemiol 2018, 2, No. e010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Maisonet M; Terrell ML; McGeehin MA; Christensen KY; Holmes A; Calafat AM; Marcus M Maternal concentrations of polyfluoroalkyl compounds during pregnancy and fetal and postnatal growth in British girls. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 1432–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Liu Y; Peterson K Early Toxicant Exposures and the Development of Obesity in Childhood. In Childhood Obesity Causes, Consequences, and Intervention Approaches; Goran MI, Ed.; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, 2016; pp 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Braun JM Early-life exposure to EDCs: role in childhood obesity and neurodevelopment. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 2017, 13, 161–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Gyllenhammar I; Diderholm B; Gustafsson J; Berger U; Ridefelt P; Benskin JP; Lignell S; Lampa E; Glynn A Perfluoroalkyl acid levels in first-time mothers in relation to offspring weight gain and growth. Environ. Int 2018, 111, 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Lauritzen HB; Larose TL; Oien T; Sandanger TM; Odland JO; van de Bor M; Jacobsen GW Prenatal exposure to persistent organic pollutants and child overweight/obesity at 5-year follow-up: a prospective cohort study. Environ. Health 2018, 17, No. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Braun JM; Chen A; Romano ME; Calafat AM; Webster GM; Yolton K; Lanphear BP Prenatal perfluoroalkyl substance exposure and child adiposity at 8 years of age: The HOME study. Obesity 2016, 24, 231–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Høyer BB; Ramlau-Hansen CH; Vrijheid M; Valvi D; Pedersen HS; Zviezdai V; Jonsson BA; Lindh CH; Bonde JP; Toft G Anthropometry in 5-to 9-Year-Old Greenlandic and Ukrainian Children in Relation to Prenatal Exposure to Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances. Environ. Health Perspect 2015, 123, 841–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Mora AM; Oken E; Rifas-Shiman SL; Webster TF; Gillman MW; Calafat AM; Ye X; Sagiv SK Prenatal Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Adiposity in Early and Mid-Childhood. Environ. Health Perspect 2017, 125, 467–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Halldorsson TI; Rytter D; Haug LS; Bech BH; Danielsen I; Becher G; Henriksen TB; Olsen SF Prenatal exposure to perfluorooctanoate and risk of overweight at 20 years of age: a prospective cohort study. Environ. Health Perspect 2012, 120, 668–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Andersen CS; Fei C; Gamborg M; Nohr EA; Sorensen TI; Olsen J Prenatal exposures to perfluorinated chemicals and anthropometry at 7 years of age. Am. J. Epidemiol 2013, 178, 921–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hartman TJ; Calafat AM; Holmes AK; Marcus M; Northstone K; Flanders WD; Kato K; Taylor EV Prenatal Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Body Fatness in Girls. Child. Obes 2017, 13, 222–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Manzano-Salgado CB; Casas M; Lopez-Espinosa MJ; Ballester F; Iniguez C; Martinez D; Romaguera D; Fernandez-Barres S; Santa-Marina L; Basterretxea M; Schettgen T; Valvi D; Vioque J; Sunyer J; Vrijheid M Prenatal Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Cardiometabolic Risk in Children from the Spanish INMA Birth Cohort Study. Environ. Health Perspect 2017, 125, No. 097018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Karlsen M; Grandjean P; Weihe P; Steuerwald U; Oulhote Y; Valvi D Early-life exposures to persistent organic pollutants in relation to overweight in preschool children. Reprod. Toxicol 2017, 68, 145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Domazet SL; Grontved A; Timmermann AG; Nielsen F; Jensen TK Longitudinal Associations of Exposure to Perfluoroalkylated Substances in Childhood and Adolescence and Indicators of Adiposity and Glucose Metabolism 6 and 12 Years Later: The European Youth Heart Study. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 1745–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Barry V; Darrow LA; Klein M; Winquist A; Steenland K Early life perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) exposure and overweight and obesity risk in adulthood in a community with elevated exposure. Environ. Res 2014, 132, 62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Cardenas A; Hauser R; Gold DR; Kleinman KP; Hivert MF; Fleisch AF; Lin PD; Calafat AM; Webster TF; Horton ES; Oken E Association of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances With Adiposity. JAMA Network Open 2018, 1, No. e181493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Tian YP; Zeng XW; Bloom MS; Lin S; Wang SQ; Yim SHL; Yang M; Chu C; Gurram N; Hu LW; Liu KK; Yang BY; Feng D; Liu RQ; Nian M; Dong GH Isomers of perfluoroalkyl substances and overweight status among Chinese by sex status: Isomers of C8 Health Project in China. Environ. Int. 2019, 124, 130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Fassler CS; Pinney SE; Xie C; Biro FM; Pinney SM Complex relationships between perfluorooctanoate, body mass index, insulin resistance and serum lipids in young girls. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, No. 108558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Nelson JW; Hatch EE; Webster TF Exposure to polyfluoroalkyl chemicals and cholesterol, body weight, and insulin resistance in the general U.S. population. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Timmermann CA; Rossing LI; Grontved A; Ried-Larsen M; Dalgard C; Andersen LB; Grandjean P; Nielsen F; Svendsen KD; Scheike T; Jensen TK Adiposity and glycemic control in children exposed to perfluorinated compounds. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 2014, 99, E608–E614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Braun JM; Kalloo G; Chen A; Dietrich KN; Liddy-Hicks S; Morgan S; Xu Y; Yolton K; Lanphear BP Cohort Profile: The Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment (HOME) study. Int. J. Epidemiol 2017, 46, No. 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Braun JM; Buckley JP; Cecil KM; Chen A; Kalkwarf HJ; Lanphear BP; Xu Y; Woeste A; Yolton K Adolescent follow-up in the Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment (HOME) Study: cohort profile. BMJ Open 2020, 10, No. e034838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kato K; Basden BJ; Needham LL; Calafat AM Improved selectivity for the analysis of maternal serum and cord serum for polyfluoroalkyl chemicals. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 2133–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Zhang H; Yolton K; Webster GM; Ye X; Calafat AM; Dietrich KN; Xu Y; Xie C; Braun JM; Lanphear BP; Chen A Prenatal and childhood perfluoroalkyl substances exposures and children’s reading skills at ages 5 and 8years. Environ. Int 2018, 111, 224–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).CDC. CDC Growth Charts. http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/ (March 21).

- (35).Micklesfield LK; Goedecke JH; Punyanitya M; Wilson KE; Kelly TL Dual-energy X-ray performs as well as clinical computed tomography for the measurement of visceral fat. Obesity 2012, 20, 1109–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Weber DR; Moore RH; Leonard MB; Zemel BS Fat and lean BMI reference curves in children and adolescents and their utility in identifying excess adiposity compared with BMI and percentage body fat. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 2013, 98, 49–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kingsley SL; Eliot MN; Kelsey KT; Calafat AM; Ehrlich S; Lanphear BP; Chen A; Braun JM Variability and predictors of serum perfluoroalkyl substance concentrations during pregnancy and early childhood. Environ. Res 2018, 165, 247–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Freemark M Determinants of Risk for Childhood Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med 2018, 379, 1371–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Romano ME; Xu Y; Calafat AM; Yolton K; Chen A; Webster GM; Eliot MN; Howard CR; Lanphear BP; Braun JM Maternal serum perfluoroalkyl substances during pregnancy and duration of breastfeeding. Environ. Res 2016, 149, 239–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Braun JM; Daniels JL; Poole C; Olshan AF; Hornung R; Bernert JT; Xia Y; Bearer C; Barr DB; Lanphear BP A prospective cohort study of biomarkers of prenatal tobacco smoke exposure: the correlation between serum and meconium and their association with infant birth weight. Environ. Health 2010, 9, No. 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Liu Y; Tellez-Rojo MM; Sanchez BN; Zhang Z; Afeiche MC; Mercado-Garcia A; Hu H; Meeker JD; Peterson KE Early lead exposure and pubertal development in a Mexico City population. Environ. Int 2019, 125, 445–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Kowalski KC; Crocker PR; Donen RM The Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children (PAQ-C) and Adolescents (PAQ-A) Manual; College of Kinesiology, University of Saskatchewan, 2004; Vol. 87. [Google Scholar]

- (43).NCI. The Healthy Eating Index–Population Ratio Method; National Cancer Institute, 2020; https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/hei/population-ratio-method.html (May 05, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- (44).Sánchez BN; Hu H; Litman HJ; Tellez-Rojo MM Statistical methods to study timing of vulnerability with sparsely sampled data on environmental toxicants. Environ. Health Perspect 2011, 119, 409–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Kendrick J; Sharma S; Holmen J; Palit S; Nuccio E; Chonchol M Kidney disease and maternal and fetal outcomes in pregnancy. Am. J. Kidney Dis 2015, 66, 55–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Stanifer JW; Stapleton HM; Souma T; Wittmer A; Zhao X; Boulware LE Perfluorinated Chemicals as Emerging Environmental Threats to Kidney Health: A Scoping Review. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 2018, 13, 1479–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Woo Baidal JA; Locks LM; Cheng ER; Blake-Lamb TL; Perkins ME; Taveras EM Risk Factors for Childhood Obesity in the First 1,000 Days: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Prev. Med 2016, 50, 761–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Oken E; Kleinman KP; Rich-Edwards J; Gillman MW A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC Pediatr. 2003, 3, No. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Jain RB Effect of pregnancy on the levels of selected perfluoroalkyl compounds for females aged 17–39 years: data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2008. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2013, 76, 409–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Akinbami LJ; Ogden CL Childhood overweight prevalence in the United States: the impact of parent-reported height and weight. Obesity 2009, 17, 1574–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Hattori A; Sturm R The obesity epidemic and changes in self-report biases in BMI. Obesity 2013, 21, 856–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Mamsen LS; Bjorvang RD; Mucs D; Vinnars MT; Papadogiannakis N; Lindh CH; Andersen CY; Damdimopoulou P Concentrations of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in human embryonic and fetal organs from first, second, and third trimester pregnancies. Environ. Int 2019, 124, 482–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Rinaudo P; Wang E Fetal programming and metabolic syndrome. Annu. Rev. Physiol 2012, 74, 107–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Janesick AS; Blumberg B Obesogens: an emerging threat to public health. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 2016, 214, 559–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Zhang L; Ren XM; Wan B; Guo LH Structure-dependent binding and activation of perfluorinated compounds on human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 2014, 279, 275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Lopez-Espinosa MJ; Mondal D; Armstrong B; Bloom MS; Fletcher T Thyroid function and perfluoroalkyl acids in children living near a chemical plant. Environ. Health Perspect 2012, 120, 1036–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Winquist A; Steenland K Perfluorooctanoic acid exposure and thyroid disease in community and worker cohorts. Epidemiology 2014, 25, 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Melzer D; Rice N; Depledge MH; Henley WE; Galloway TS Association between serum perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and thyroid disease in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Environ. Health Perspect 2010, 118, 686–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Shi Z; Zhang H; Ding L; Feng Y; Xu M; Dai J The effect of perfluorododecanonic acid on endocrine status, sex hormones and expression of steroidogenic genes in pubertal female rats. Reprod. Toxicol 2009, 27, 352–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Benninghoff AD; Bisson WH; Koch DC; Ehresman DJ; Kolluri SK; Williams DE Estrogen-like activity of perfluoroalkyl acids in vivo and interaction with human and rainbow trout estrogen receptors in vitro. Toxicol. Sci 2011, 120, 42–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Leeners B; Geary N; Tobler PN; Asarian L Ovarian hormones and obesity. Hum. Reprod. Update 2017, 23, 300–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Wolf CJ; Takacs ML; Schmid JE; Lau C; Abbott BD Activation of mouse and human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha by perfluoroalkyl acids of different functional groups and chain lengths. Toxicol. Sci 2008, 106, 162–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Abbott BD; Wolf CJ; Das KP; Zehr RD; Schmid JE; Lindstrom AB; Strynar MJ; Lau C Developmental toxicity of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) is not dependent on expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-alpha (PPAR alpha) in the mouse. Reprod. Toxicol 2009, 27, 258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Pizzurro DM; Seeley M; Kerper LE; Beck BD Interspecies differences in perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) tox-icokinetics and application to health-based criteria. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 2019, 106, 239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Manzano-Salgado CB; Casas M; Lopez-Espinosa MJ; Ballester F; Iniguez C; Martinez D; Costa O; Santa-Marina L; Pereda-Pereda E; Schettgen T; Sunyer J; Vrijheid M Prenatal exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances and birth outcomes in a Spanish birth cohort. Environ. Int 2017, 108, 278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Voerman E; Santos S; Patro Golab B; Amiano P; Ballester F; Barros H; Bergstrom A; Charles MA; Chatzi L; Chevrier C; Chrousos GP; Corpeleijn E; Costet N; Crozier S; Devereux G; Eggesbo M; Ekstrom S; Fantini MP; Farchi S; Forastiere F; Georgiu V; Godfrey KM; Gori D; Grote V; Hanke W; Hertz-Picciotto I; Heude B; Hryhorczuk D; Huang RC; Inskip H; Iszatt N; Karvonen AM; Kenny LC; Koletzko B; Kupers LK; Lagstrom H; Lehmann I; Magnus P; Majewska R; Makela J; Manios Y; McAuliffe FM; McDonald SW; Mehegan J; Mommers M; Morgen CS; Mori TA; Moschonis G; Murray D; Chaoimh CN; Nohr EA; Nybo Andersen AM; Oken E; Oostvogels A; Pac A; Papadopoulou E; Pekkanen J; Pizzi C; Polanska K; Porta D; Richiardi L; Rifas-Shiman SL; Ronfani L; Santos AC; Standl M; Stoltenberg C; Thiering E; Thijs C; Torrent M; Tough SC; Trnovec T; Turner S; van Rossem L; von Berg A; Vrijheid M; Vrijkotte TGM; West J; Wijga A; Wright J; Zvinchuk O; Sorensen TIA; Lawlor DA; Gaillard R; Jaddoe VWV Maternal body mass index, gestational weight gain, and the risk of overweight and obesity across childhood: An individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, No. e1002744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.