Abstract

Tissue-resident CD8+ T cells (CD8+ TRM) populate lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues after infections as first line of defense against re-emerging pathogens. To achieve host protection, CD8+ TRM have developed surveillance strategies that combine dynamic interrogation of pMHC complexes on local stromal and hematopoietic cells with long-term residency. Factors mediating CD8+ TRM residency include CD69, a surface receptor opposing the egress-promoting S1P1, CD49a, a collagen-binding integrin, and CD103, which binds E-cadherin on epithelial cells. Moreover, the topography of the tissues of residency may influence TRM retention and surveillance strategies. Here, we provide a brief summary of these factors to examine how CD8+ TRM reconcile constant migratory behavior with their long-term commitment to local microenvironments, with a focus on epithelial barrier organs and exocrine glands with mixed connective—epithelial tissue composition.

Keywords: tissue-resident T cells, epidermal barrier, salivary gland, chemokine, integrin

Introduction

During viral infections, Ag-specific naïve CD8+ T cells (TN) become activated in reactive secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs), and change their gene expression pattern and metabolism to differentiate into proliferating cytotoxic effector T cells (TEFF) (1, 2). During the effector phase, TEFF are subdivided into KLRG1+ CD127− short-lived effector T cells and KLRG1− CD127+ memory precursor effector cells, with a larger potential to generate long-lived memory cells in the latter compartment (3). TEFF killing of infected cells in inflamed tissue requires direct cell-to-cell contact to identify cognate peptide major histocompatibility complexes (pMHC) on target cells, which leads to release of granzymes and perforin for induction of apoptosis (4, 5). Once intracellular infections have been cleared, memory CD8+ T cells patrol the body for rapid protective recall responses upon secondary pathogen encounter. Depending on their surface marker expression and trafficking patterns, distinct subsets of memory CD8+ T cells are classified (6). Central memory T cells (TCM) maintain the ability to recirculate through SLOs through expression of the homing receptors L-selectin (CD62L) and the chemokine receptor CCR7, a characteristic shared with TN. Recent work has shown that TCM can also be rapidly recruited to sites of inflammation outside lymphoid tissue (7). Effector memory T cells (TEM) lack CD62L and CCR7 expression and are thought to patrol non-lymphoid tissues (NLTs), although their precise functions are still not well-defined (8). Peripheral memory CD8+ T cells (TPM) have been recently described based on intermediate expression of the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 as predominant subset surveying NLTs (9). Finally, self-renewing, non-recirculating tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) populate barrier organs after clearing of an infection as first line of defense, both in mice and humans (10–17). In contrast to circulating memory T cell subsets, TRM are in a disequilibrium with blood as they are retained for months or years within their tissue of residency. Recent data suggest that tissue-residency vs. circulating memory potential is already imprinted during priming in lymphoid tissue. Migratory dendritic cells (DCs) from skin and gut epithelium present active transforming growth factor (TGF)-β to recirculating CD8+ TN, which preconditions these cells to form TRM in a skin vaccination model (18). Such conditioning is another example of lymphoid tissue-directed steering of ensuing immune responses, such as reported for differential homing receptor induction in skin-vs. gut-draining lymphoid tissue (19). In line with this observation, a tissue-resident gene expression signature is readily detectable in early circulating TEFF cells prior to entry into NLTs (20). Notably, presence of cognate antigen at infiltrated target sites is not a prerequisite for TRM formation, although it increases their local abundance (21). Finally, in addition to sites of microbial infection, CD8+ T cells with a TRM signature are also detectable in tumors and in autoimmune inflammatory conditions, where these cells exert protective and detrimental effects, respectively (17).

Studies following the development of epidermal CD8+ TRM have shown that KLRG1− precursor cells enter the dermis during the early effector response and that their entry into the epidermis involves the action of keratinocyte-secreted chemokines that bind to CXCR3 and CCR10 expressed on skin-homing T cells (22, 23). The cytokines IL-15 and TGF-β are involved in the formation and survival of epidermal TRM. In particular, TGF-β transactivation by keratinocytes increases expression of the integrin chain CD103, which plays a role in tissue retention of epidermal TRM (see below) (22, 24, 25). TRM are characterized by a core transcriptional program mediated by the transcription factors Hobit and Blimp1, as well as Runx3 and Notch (26–28). As a local adaptation to the lipid-rich skin environment, fatty acid metabolism, and mitochondrial functions regulate epidermal TRM development and survival (29). In addition to epithelial barriers, TRM have been identified in virtually all organs including central nervous system (CNS), exocrine glands, lungs, liver, kidney, bone marrow, reproductive tract, as well as tumors (10, 17, 30–36). Notably, far from being a homogeneous population, TRM display considerable heterogeneity (37–39) and interact with diverse, undefined non-hematopoietic cells during local reactivation (40). Furthermore, a recent report using a Hobit expression/fate reporter mouse line has uncovered that TRM have the capacity to de-differentiate to TEFF, which occurs in parallel to Hobit downregulation after TCR activation (41).

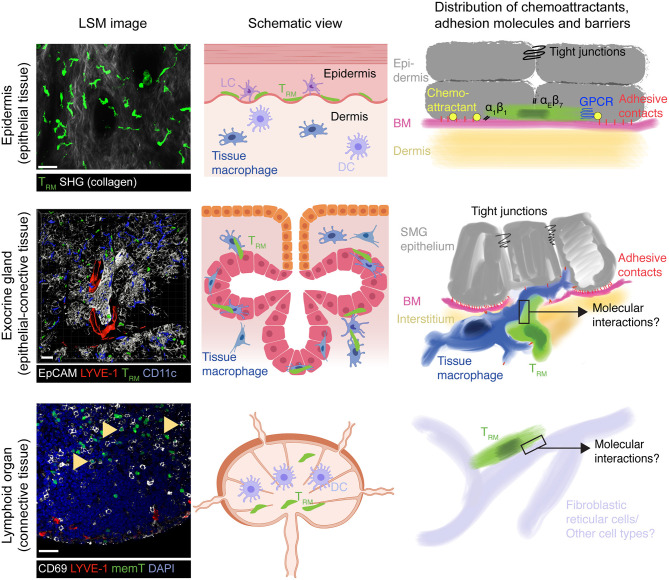

The localization of TRM to sites of previous pathogen infection poise them to rapidly respond to secondary infections. Accordingly, TRM release cytokines after activation and express high levels of effector molecules such as granzyme B for target cell killing. The protective role for TRM is exemplified by studies in barrier sites of the skin and mucosal surfaces such as the female reproductive tract, where these cells lodge within the epithelium. Antigen re-challenge experiments have shown that TRM act as first-line defense by inducing a tissue-wide alert state, in part via IFN-γ secretion (42–48). These signals relay to innate immune cells for additional cytokine release that results in recruitment of immune cells to the site of pathogen re-emergence, essentially reversing the paradigm that activation of the innate immune system always precedes the adaptive immunity activation. Thus, while TRM also undergo bystander activation through inflammatory cytokines (49, 50), local immune surveillance for cognate pMHC presented on host cells is a key feature of CD8+ TRM cells to provide pathogen-specific, long-lasting host protection. To achieve this extraordinary feat, CD8+ TRM acquire the ability to infiltrate and physically scan their environment for infected cells within virtually any host organ, while avoiding inadvertent tissue exit via blood or lymphatic vessels or out of an epithelial barrier. Accordingly, CD8+ TRM have been found to be patrolling vascular compartments, such as liver sinusoids (51), as well as neuronal and muscle tissue (32, 52). Other anatomical locations surveilled by TRM vary in their content of epithelial and connective tissue: (i) predominantly epithelial (e.g., epidermis and mucosal epithelium), (ii) mixed epithelial—connective (e.g., exocrine and endocrine glands), and (iii) predominantly connective tissue (e.g., lymph nodes and spleen) (Figure 1). Here, we will provide a brief overview on tissue retention and surveillance strategies focusing on data gained in mouse models of skin vs. salivary glands as prototypical epithelial barrier site vs. exocrine gland.

Figure 1.

Model of TRM surveillance strategies according to organ topography. In epithelial barrier tissues such as epidermis, TRM mainly locate on top of the basement membrane (BM) separating connective tissue from the epithelium, which themselves are connected by adherens and tight junctions. Both BM and tight junctions serve as physical boundaries to TRM foraging, essentially restricting their motility to a 2D-like surface. Chemoattractants, either constitutively expressed or induced by microbial presence, together with α1 and αE integrins further re-enforce this restricted migration pattern to ensure long-term retention by preventing inadvertent loss of scanning TRM outside the epithelial barrier. In exocrine glands such as the SMG (mixed arborized epithelial—connective tissue), tight junctions between secretory epithelial cells may constitute a similar barrier to prevent loss of TRM into the acini or duct lumen. Yet, the BM separating secretory epithelium from supporting interstitium remains permissive for two-way traffic into and out of epithelial cell layers, which is facilitated in SMG by tissue macrophages. Accordingly, non-inflamed secretory epithelial cells presumably secrete only low levels of chemoattractants that would otherwise retain TRM in this site. This mode of tissue scanning permits rapid accumulation of TRM to sites of secondary pathogen encounters, which would be hampered if TRM were confined exclusively to the epithelial cell layer. While CD69+ memory CD8+ cells also locate to lymphoid tissue following a viral infection (arrowheads), their function and dynamic interactions with local cells enabling their long-term retention and host protective capacity remain unknown. Similarly, it remains unclear whether SLO TRM retain responsiveness to inflammatory chemokines as their counterparts in epithelial layers and exocrine glands. All confocal images show GFP+ OT-I CD8+ TCR transgenic T cells at >30 days following systemic or local (skin) virus infections. LSM, laser scanning microscope; SHG, second harmonic generation; LC, Langerhans cells; DC, Dendritic cells; BM, basement membrane, memT, CD8+ memory T cells. Scale bar LSM images, 30 μm. Middle panels created with https://biorender.com/.

Multiple Layers of Tissue Retention Cooperate for Long-Term TRM Surveillance of Epithelial Barrier Tissue

Expression of CD69 is the most commonly employed marker to define TRM in all locations, although it is not an exclusive TRM marker and its expression does not necessarily correlate with establishment of long-term resident TRM populations (53, 54). CD69 is a cis-antagonist of the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) required for egress via lymphatic vessels, which drain interstitial fluid from organs and which contain higher amounts of S1P than tissue (55, 56). TRM also reduce S1P1 production on a transcriptional level, which is prerequisite for establishing long-term residency (57). In epithelial tissues, most TRM express CD103, which is the αE chain of the E-cadherin receptor αEβ7 (6, 58). E-cadherin is expressed by epithelial cells, where it promotes their homotypic adhesion. In line with this, CD103 promotes the long-term persistence of TRM in skin, presumably by retaining these cells within the keratinocyte layer (22). Epidermal CD8+ TRM further upregulate the collagen receptor α1β1, which also contributes to their long-term permanence (59, 60). Finally, TRM increase expression of the negative regulator of chemoattractant receptor signaling, regulator of G-protein-coupled signaling 1 (RGS1) (61, 62). RGS1 and related members of the RGS family activate the GTPase activity of GTP-bound Gαi, which leads to a cessation of Gαi-coupled receptors signaling (63). RGS-mediated blunted responsiveness to chemoattractants, such as S1P, likely contributes to long-term residency, although experimental evidence is still lacking. Taken together, CD8+ TRM have multiple molecular modules at their disposal that in combination reduce the probability to accidentally exit their tissue of residency during homeostatic surveillance. Moreover, the structure of the epithelial microenvironment likely contributes to long-term retention of TRM. Epidermal TRM lodge on top of a dense basement membrane (BM) separating underlying connective tissue from the overlying epithelium, and such BM form physical barriers that limit leukocyte dissemination (64). At their apical border, epithelial cells are attached via tight junctions that form a barrier for T cell exit out of the epidermis or into the gut lumen, respectively (65, 66). These factors likely help epithelial TRM to establish long-term tissue-residency as a prerequisite for life-long protection at previously infected sites (Figure 1).

Within their tissue of residency, epidermal TRM physically scan the local cell neighborhood for cognate pMHC. During this process, they display characteristic elongated shapes with numerous dendrites that constantly extend and contract and move in a Gαi-dependent manner with speeds of 1–2 μm/min along the bottom keratinocyte layer, resembling motility on a 2D layer (23, 67, 68). Reconstruction of TRM motility in human skin biopsies revealed that these cells occasionally traversed the papillary dermis, and are therefore less strictly confined to the epidermis as observed in mouse skin (69). Both TRM dendricity and motility contribute to efficient scanning of the epidermis (67). Lack of neither the skin-selective chemokine receptors CCR8 or CCR10 (70), nor CXCR3 or CXCR6 affect baseline motility of epidermal TRM, although lack of CXCR6 reduces TRM dendricity (23). During secondary viral spread, epidermal CD8+ T cells use CXCR3 to follow local chemokine signals and accumulate around infected cells (4, 48). In sum, epidermal TRM maintain responsiveness to inflammatory chemokines despite their Gαi-dependent basal motility, suggesting that these chemoattractants override their homeostatic, as yet undefined GPCR input.

Lack of the α1β1 integrin but not CD103 leads to a loss of the dendrite-shaped TRM morphology (23, 60), suggesting that these cells form transient anchors with their protrusions interacting with extracellular matrix. The precise molecular composition of these transient α1β1-mediated adhesions remains to be characterized but they likely differ from the more long-lasting anchoring of tissue macrophage protrusions (71). Furthermore, ex vivo migration analysis of lung TRM uncovered a role for CD49a in facilitating TRM translocation, whereas CD103 did not promote motility (72). Instead, lack of CD103 leads to an increase in epidermal TRM speeds in vivo, suggesting a primary role for this integrin in tissue retention (23). The impact of CD49a on in vivo TRM motility parameters has not been determined yet.

Similar to CD49a deficiency, microtubule network depolymerization following nocodazole treatment leads to a loss of the characteristic TRM dendricity (23). This phenomenon is likely due to global release of Rho-activating factor ArhGEF2 otherwise trapped in microtubules (73). Controlled release of ArhGEF2 from depolymerizing microtubules has been recently shown to play an important role in retracting protrusions that are not following the nuclear translocation path during amoeboid cell displacement (74). This pathway serves therefore as a proprioceptive mechanism to control amoeboid cell shape in complex environments such as formed by the tightly packed keratinocyte layer, and is essential to avoid accidental cell rupture. A role for ArhGEF2 in facilitating epidermal TRM motility has thus far not been experimentally addressed. Taken together, continuous retention of epithelial TRM is mediated by multiple integrin receptor interactions and homeostatic GPCR signaling. Long-term TRM colonization may be further facilitated by “layered” architecture of epidermis with a BM separating the underlying connective tissue and the tight junction seal on the apical part of the epithelial layer (Figure 1).

TRM Lodging and Surveillance of “Non-Barrier” NLTs

In addition to the well-studied epidermis and small intestinal epithelium that are constitutively exposed to microbes, TRM lodge to organs that are less subjected to constant microbial challenge and contain few or no E-cadherin-expressing epithelial layers. These organs include CNS, kidney, submandibular salivary glands (SMG), liver, and bone marrow (10, 16, 75, 76). In contrast to epidermis where CD8+ TRM are embedded between non-vascularized epithelial cells, these complex organs contain extensive blood and lymphatic vascular systems, innervation, fibroblasts, tissue-resident macrophages, and innate immune cells, as well as in some cases arborized secretory epithelium. In addition to distinct tissue-specific cellular composition (e.g., kidney tubular cells, hepatocytes, CXCL12-abundant reticular cells of the bone marrow) and receptor-ligand expression patterns, these organs differ in their metabolic activity (e.g., liver) or immunosuppressive environment (e.g., reproductive tract) (77, 78). Furthermore, beyond the biochemical and cellular properties of individual tissues, physical parameters such as topography, substrate stiffness, and confinement influence cell-based immune responses and cross-talk with their environment (79, 80). To date, little is known about how the local microenvironment in these organs affects the phenotype and mechanism of surveillance of TRM during homeostasis and recall responses. While the high expression of CD69, CD49a, and RGS1 on a majority of non-barrier NLT TRM suggests similar roles as in epithelial barrier tissues, CD103 expression is not required for long-term retention of TRM in SMG, in contrast to skin (81, 82). Another key issue is whether memory T cells from distinct anatomical locations employ tissue-specific mechanisms of host surveillance.

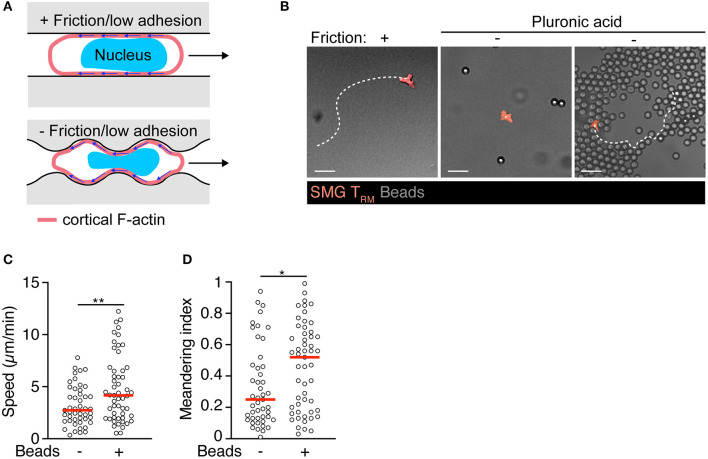

In a recent study, we have found that TRM lodging in SMG acquire a motility program distinct from TCM and epidermal TRM (83). In contrast to memory T cells isolated from lymphoid tissue or epidermis, in vivo observations suggested SMG CD8+ TRM were largely refractory to pharmacological inhibition of Gαi-protein-coupled receptors or integrin adhesion molecules during homeostatic tissue surveillance, although they retained the ability to respond to inflammatory chemokines and expressed high levels of the CD103, CD49a, CD49d, and CD11a integrins (83). While integrin-independent migration in 3D matrices has become a widely accepted concept in cell biology based on studies with cell lines and DCs (84), several studies demonstrated integrin involvement during immune surveillance of skin T cells (23, 85). As direct evidence for specific adhesion-independent motility, TRM isolated from salivary glands displayed spontaneous motility under 2D confinement in the absence of integrin ligands or chemoattractants. Adhesion-free motility in 2D conditions was reported for large, blebbing carcinoma cells, based on non-specific friction mediated by a large interface between migrating cells and substrates (Figure 2A) (86, 87). Similarly, we observed that non-specific substrate friction is sufficient to trigger intrinsic SMG TRM motility in 2D confinement (83). In turn, TRM isolated from salivary glands did not show displacement on “slippery surfaces,” i.e., in presence of EDTA or when surfaces were passivated with pluronic acid, which reduces friction below a threshold for cell translocation (Figures 2B–D). Notably, these cells regained the capability to translocate in absence of substantial friction when a 3D geometry was created by immotile neighboring objects (Figures 2B–D). This motility mode correlated with continuous changes in cell shapes during migration through microchannels formed by the microenvironment. In this setting, SMG TRM continuously form multiple simultaneous protrusions that probe the environmental geometry, leading to their insertion into permissive gaps and subsequent cell body translocation (83). In the complex 3D exocrine organ architecture, tissue macrophages embedded within the epithelial and connective tissue compartments contributed to generate available extracellular space for protrusion-forming TRM (83).

Figure 2.

Intrinsic motility of SMG TRM triggered by environmental topography. (A) Model for autonomous exocrine gland TRM motility generated by baseline retrograde F-actin flow coupled via non-specific substrate friction or low adhesiveness under physical confinement. In addition, under completely non-adhesive conditions, cell propulsion can be generated through bending of the retrograde cortical actin flow by the environmental topography. Adapted from Reversat et al. (88). (B) Exemplary track of isolated SMG TRM in “under agarose” confinement on human serum albumin with and without pluronic acid (PA) passivation to abolish residual friction or lodged between 7 μm-polystyrene bead clusters. Scale bar, 20 μm. (C) TRM speeds within or outside of polystyrene bead clusters in presence of PA. (D) TRM meandering index within or outside of polystyrene bead clusters in presence of PA. Data were analyzed by unpaired t-test (C) or Mann–Whitney test (D). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

How do TRM shape changes generate tractive force for cell translocation under these conditions? A recent study has identified adhesion-free cellular locomotion driven by microenvironmental architecture (Figure 2A) (88). Thus, a permissive local topography facilitates cell motility by adapting the cell shape to features of the environment such as crevices and serrated surfaces. At these non-smooth surfaces, rearward cortical F-actin flow generates non-normal forces that results in forward cell motility, rendering cellular translocation autonomous from external influences (Figure 2A). These data provide a model for adhesion-free TRM motility in the absence of friction, and highlight the multiple ways TRM are able to integrate chemical signals (e.g., chemoattractants) and tissue architecture to patrol complex 3D structures such as secretory glands.

What may be the advantages of such a non-canonical migration mode for immune surveillance of mixed connective—epithelial tissues? In contrast to the epidermally restricted migratory behavior of CD8+ skin TRM (89), exocrine gland TRM display a bidirectional trafficking pattern into and out of epithelial layers, a process facilitated by tissue macrophages (Figure 1) (83). Such bidirectional trafficking would be perturbed by epithelial chemokine secretion, which could furthermore lead to continuous leukocyte influx and exacerbated inflammation after clearance of infection. Instead, this modus allows TRM to remain responsive to inflammatory chemokines that are locally secreted at sites of pathogen re-emergence. In this context, not being confined to arborized secretory epithelium shortens the pathlength that TRM need to travel in order to accumulate at local sites of inflammation. Furthermore, as ECM proteins and other integrin ligands differ in distinct NLTs (90, 91), integrin-independent motility may endow TRM subsets with flexible topography-driven organ surveillance in non-epithelial barrier sites. A non-proteolytic pathway is beneficial to preserve the integrity of the target tissue, as it does not require constant repair of newly generated discontinuities in the ECM matrix (92). The scanning strategy adopted by homeostatic SMG TRM resembles the migration pattern of T cell blasts in 3D collagen networks, where these cells routinely bypass dense collagen areas, while probing the environment for permissive gaps for cell body translocation (93). In sum, these observations are consistent with a model where certain NLT TRM switch during homeostatic immune surveillance to a self-motile “autopilot” mode supported by tissue macrophage topography, while remaining susceptible to locally produced inflammatory signals for concerted cytotoxic activity. Whether CD8+ TRM have adapted a comparable mode for other non-barrier NLTs and whether autonomous motility is shared by other tissue-resident leukocytes, such as CD4+ TRM, NK or innate lymphoid cells, remains unknown.

Discussion

Here, we put the general tissue architecture of epidermis and salivary glands as prototype epithelial vs. mixed epithelial—connective tissues into context with published observations on the dynamic surveillance strategies adapted by TRM. Reflecting the acknowledged heterogeneity, TRM develop distinct tissue-specific scanning modalities, i.e., chemokine- and integrin-dependent and -independent in epidermis and exocrine glands, respectively, to balance retention and local pMHC interrogation. Independent of their baseline homeostatic migration mode, TRM remain susceptible to inflammatory chemokines produced during pathogen re-encounter, which facilitates their clustering at target sites, perhaps reflecting the low killing rate of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells against stromal cell targets (94). Furthermore, certain organs such as epithelial barrier sites might have a higher abundance of promigratory factors in steady state owing to their continuous exposure to microbes. In contrast, non-barrier NLTs may generally express low amounts of chemoattractants in absence of inflammation that demand an adaptation of local immune cells. Recent data suggest that nuclear sensing of confinement may contribute to generate cellular translocation in the absence of external factors (95, 96). Yet, it remains unclear whether or in which NLTs this contributes to TRM surveillance patterns.

A recent observation made by Masopust and colleagues was the presence of bona fide CD69+ TRM in the red pulp (RP) of spleen and medullary area of LNs (97) (Figure 1), which are at least in part derived from NLT TRM precursors (53). In contrast to CD62L+ CCR7+ TCM (98), the physiological role of TRM in SLO remains essentially unknown to date. Notably, recent data suggest that in humans a large proportion of memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are CD69+ bona fide TRM, including in LNs and spleen (99). While some of these cells may retain the capacity to recirculate (53), these observations suggest the presence of specific TRM niches with a potential role during re-infection, e.g., via cytokine secretion and/or de-differentiation into TEFF (41). At the same time, the close spatial proximity of spleen TRM to vascular sinuses in the RP (97) raises the question how these cells reconcile dynamic tissue surveillance with long-term retention in a connective tissue with few major tissue barriers such as extensive tight junctions and basement membranes as compared to epithelial barrier sites (Figure 1) (100). Taken together, many incognita remain on the organ-specific TRM cross-talk with the local microenvironment. Combining in vivo analysis with high resolution single cell technologies to take into account cell heterogeneity will shed light on these open points.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xenia Ficht and Flavian Thelen for critical reading of the manuscript and acknowledge the support of the BioImage Light Microscopy and Cell Analytics Facilities of the University of Fribourg.

Footnotes

Funding. The Stein laboratory was funded by Swiss National Foundation grants 31003A_172994, CRSII5_170969 and CRSK-3_190484 (to JS).

References

- 1.Buck MD, O'Sullivan D, Pearce EL. T cell metabolism drives immunity. J Exp Med. (2015) 212:1345–60. 10.1084/jem.20151159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masopust D, Schenkel JM. The integration of T cell migration, differentiation and function. Nat Rev Immunol. (2013) 13:309–20. 10.1038/nri3442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshi NS, Cui W, Chandele A, Lee HK, Urso DR, Hagman J, et al. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8(+) T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. (2007) 27:281–95. 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffith JW, Sokol CL, Luster AD. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: positioning cells for host defense and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. (2014) 32:659–702. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein JV, Ruef N. Regulation of global CD8+ T-cell positioning by the actomyosin cytoskeleton. Immunol Rev. (2019) 289:232–49. 10.1111/imr.12759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jameson SC, Masopust D. Understanding subset diversity in T cell memory. Immunity. (2018) 48:214–26. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osborn JF, Mooster JL, Hobbs SJ, Munks MW, Barry C, Harty JT, et al. Enzymatic synthesis of core 2 O-glycans governs the tissue-trafficking potential of memory CD8+ T cells. Sci Immunol. (2017) 2:eaan6049. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aan6049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. (1999) 401:708–12. 10.1038/44385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerlach C, Moseman EA, Loughhead SM, Alvarez D, Zwijnenburg AJ, Waanders L, et al. The chemokine receptor CX3CR1 defines three antigen-experienced CD8 T cell subsets with distinct roles in immune surveillance and homeostasis. Immunity. (2016) 45:1270–84. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller SN, Mackay LK. Tissue-resident memory T cells: local specialists in immune defence. Nat Rev Immunol. (2016) 16:79–89. 10.1038/nri.2015.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan X, Rudensky AY. Hallmarks of tissue-resident lymphocytes. Cell. (2016) 164:1198–211. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosato PC, Beura LK, Masopust D. Tissue resident memory T cells and viral immunity. Curr Opin Virol. (2017) 22:44–50. 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enamorado M, Khouili SC, Iborra S, Sancho D. Genealogy, dendritic cell priming, and differentiation of tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells. Front Immun. (2018) 9:1751. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gebhardt T, Palendira U, Tscharke DC, Bedoui S. Tissue-resident memory T cells in tissue homeostasis, persistent infection, and cancer surveillance. Immunol Rev. (2018) 283:54–76. 10.1111/imr.12650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takamura S. Niches for the long-term maintenance of tissue-resident memory T cells. Front Immun. (2018) 9:1214. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szabo PA, Miron M, Farber DL. Location, location, location: tissue resident memory T cells in mice and humans. Sci Immunol. (2019) 4:eaas9673. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aas9673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sasson SC, Gordon CL, Christo SN, Klenerman P, Mackay LK. Local heroes or villains: tissue-resident memory T cells in human health and disease. Cell Mol Immunol. (2020) 17:113–22. 10.1038/s41423-019-0359-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mani V, Bromley SK, Äijö T, Mora-Buch R, Carrizosa E, Warner RD, et al. Migratory DCs activate TGF-β to precondition naïve CD8+ T cells for tissue-resident memory fate. Science. (2019) 366:eaav5728. 10.1126/science.aav5728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigmundsdottir H, Butcher EC. Environmental cues, dendritic cells and the programming of tissue-selective lymphocyte trafficking. Nat Immunol. (2008) 9:981–7. 10.1038/ni.f.208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kok L, Dijkgraaf FE, Urbanus J, Bresser K, Vredevoogd DW, Cardoso RF, et al. A committed tissue-resident memory T cell precursor within the circulating CD8+ effector T cell pool. J Exp Med. (2020) 217:e20191711. 10.1084/jem.20191711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan TN, Mooster JL, Kilgore AM, Osborn JF, Nolz JC. Local antigen in nonlymphoid tissue promotes resident memory CD8+ T cell formation during viral infection. J Exp Med. (2016) 213:951–66. 10.1084/jem.20151855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackay LK, Rahimpour A, Ma JZ, Collins N, Stock AT, Hafon ML, et al. The developmental pathway for CD103(+)CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells of skin. Nat Immunol. (2013) 14:1294–301. 10.1038/ni.2744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaid A, Hor JL, Christo SN, Groom JR, Heath WR, Mackay LK, et al. Chemokine receptor-dependent control of skin tissue-resident memory T cell formation. J Immunol. (2017) 199:2451–59. 10.4049/jimmunol.1700571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nath AP, Braun A, Ritchie SC, Carbone FR, Mackay LK, Gebhardt T, et al. Comparative analysis reveals a role for TGF-β in shaping the residency-related transcriptional signature in tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0210495. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirai T, Yang Y, Zenke Y, Li H, Chaudhri VK, La Cruz Diaz De JS, et al. Competition for active TGFβ cytokine allows for selective retention of antigen-specific tissue- resident memory T cells in the epidermal niche. Immunity. (2020) 54:84–98.e5. 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackay LK, Minnich M, Kragten NAM, Liao Y, Nota B, Seillet C, et al. Hobit and Blimp1 instruct a universal transcriptional program of tissue residency in lymphocytes. Science. (2016) 352:459–63. 10.1126/science.aad2035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hombrink P, Helbig C, Backer RA, Piet B, Oja AE, Stark R, et al. Programs for the persistence, vigilance and control of human CD8+ lung-resident memory T cells. Nat Immunol. (2016) 17:1467–78. 10.1038/ni.3589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milner JJ, Toma C, Yu B, Zhang K, Omilusik K, Phan AT, et al. Runx3 programs CD8+ T cell residency in non-lymphoid tissues and tumours. Nature. (2017) 552:253–7. 10.1038/nature24993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan Y, Tian T, Park CO, Lofftus SY, Mei S, Liu X, et al. Survival of tissue-resident memory T cells requires exogenous lipid uptake and metabolism. Nature. (2017) 543:252–6. 10.1038/nature21379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belz GT, Denman R, Seillet C, Jacquelot N. Tissue-resident lymphocytes: weaponized sentinels at barrier surfaces. F1000Res. (2020) 9:691. 10.12688/f1000research.25234.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turner JE, Becker M, Mittrücker HW, Panzer U. Tissue-resident lymphocytes in the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2018) 29:389–99. 10.1681/ASN.2017060599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinbach K, Vincenti I, Kreutzfeldt M, Page N, Muschaweckh A, Wagner I, et al. Brain-resident memory T cells represent an autonomous cytotoxic barrier to viral infection. J Exp Med. (2016) 213:1571–87. 10.1084/jem.20151916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carbone FR. Tissue-resident memory T cells and fixed immune surveillance in nonlymphoid organs. J Immunol. (2015) 195:17–22. 10.4049/jimmunol.1500515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amsen D, van Gisbergen KPJM, Hombrink P, van Lier RAW. Tissue-resident memory T cells at the center of immunity to solid tumors. Nat Immunol. (2018) 19:538–46. 10.1038/s41590-018-0114-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang HD, Tokoyoda K, Radbruch A. Immunological memories of the bone marrow. Immunol Rev. (2018) 283:86–98. 10.1111/imr.12656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wein AN, McMaster SR, Takamura S, Dunbar PR, Cartwright EK, Hayward SL, et al. CXCR6 regulates localization of tissue-resident memory CD8 T cells to the airways. J Clin Exp Med. (2019) 216:2748–62. 10.1084/jem.20181308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong MT, Ong DEH, Lim FSH, Teng KWW, McGovern N, Narayanan S, et al. A high-dimensional atlas of human T cell diversity reveals tissue-specific trafficking and cytokine signatures. Immunity. (2016) 45:442–56. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar BV, Kratchmarov R, Miron M, Carpenter DJ, Senda T, Lerner H, et al. Functional heterogeneity of human tissue-resident memory T cells based on dye efflux capacities. JCI Insight. (2018) 3:e123568. 10.1172/jci.insight.123568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milner JJ, Toma C, He Z, Kurd NS, Nguyen QP, McDonald B, et al. Heterogenous populations of tissue-resident CD8+ T cells are generated in response to infection and malignancy. Immunity. (2020) 52:808–24.e7. 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Low JS, Farsakoglu Y, Amezcua Vesely MC, Sefik E, Kelly JB, Harman CCD, et al. Tissue-resident memory T cell reactivation by diverse antigen-presenting cells imparts distinct functional responses. J Exp Med. (2020) 217:e20192291. 10.1084/jem.20192291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Behr FM, Parga-Vidal L, Kragten NAM, van Dam TJP, Wesselink TH, Sheridan BS, et al. Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells shape local and systemic secondary T cell responses. Nat Immunol. (2020) 211:93–12. 10.1038/s41590-020-0723-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shin H, Iwasaki A. A vaccine strategy that protects against genital herpes by establishing local memory T cells. Nature. (2012) 491:463–7. 10.1038/nature11522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iijima N, Iwasaki A. A local macrophage chemokine network sustains protective tissue-resident memory CD4 T cells. Science. (2014) 346:93–8. 10.1126/science.1257530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schenkel JM, Fraser KA, Beura LK, Pauken KE, Vezys V, Masopust D. T cell memory. Resident memory CD8 T cells trigger protective innate and adaptive immune responses. Science. (2014) 346:98–101. 10.1126/science.1254536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stary G, Olive A, Radovic-Moreno AF, Gondek D, Alvarez D, Basto PA, et al. VACCINES. A mucosal vaccine against Chlamydia trachomatis generates two waves of protective memory T cells. Science. (2015) 348:aaa8205. 10.1126/science.aaa8205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ariotti S, Hogenbirk MA, Dijkgraaf FE, Visser LL, Hoekstra ME, Song JY, et al. Skin-resident memory CD8? T cells trigger a state of tissue-wide pathogen alert. Science. (2014) 346:101–5. 10.1126/science.1254803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kadoki M, Patil A, Thaiss CC, Brooks DJ, Pandey S, Deep D, et al. Organism-level analysis of vaccination reveals networks of protection across tissues. Cell. (2017) 171:398–413.e21. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ariotti S, Beltman JB, Borsje R, Hoekstra ME, Halford WP, Haanen JBAG, et al. Subtle CXCR3-dependent chemotaxis of CTLs within infected tissue allows efficient target localization. J Immunol. (2015) 195:5285–95. 10.4049/jimmunol.1500853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maurice NJ, Taber AK, Prlic M. The ugly duckling turned to swan: a change in perception of bystander-activated memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol. (2021) 206:455–62. 10.4049/jimmunol.2000937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ge C, Monk IR, Pizzolla A, Wang N, Bedford JG, Stinear TP, et al. Bystander activation of pulmonary Trm cells attenuates the severity of bacterial pneumonia by enhancing neutrophil recruitment. Cell Rep. (2019) 29:4236–44.e3. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.11.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernandez-Ruiz D, Ng WY, Holz LE, Ma JZ, Zaid A, Wong YC, et al. Liver-resident memory CD8+ T cells form a front-line defense against malaria liver-stage infection. Immunity. (2016) 45:889–902. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Casey KA, Fraser KA, Schenkel JM, Moran A, Abt MC, Beura LK, et al. Antigen-independent differentiation and maintenance of effector-like resident memory T cells in tissues. J Immunol. (2012) 188:4866–75. 10.4049/jimmunol.1200402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beura LK, Wijeyesinghe S, Thompson EA, Macchietto MG, Rosato PC, Pierson MJ, et al. T cells in nonlymphoid tissues give rise to lymph-node-resident memory T cells. Immunity. (2018) 48:327–38.e5. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walsh DA, Borges da Silva H, Beura LK, Peng C, Hamilton SE, Masopust D, et al. the functional requirement for CD69 in establishment of resident memory CD8+ T cells varies with tissue location. J Immunol. (2019) 203:946–55. 10.4049/jimmunol.1900052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shiow LR, Rosen DB, Brdičková N, Xu Y, An J, Lanier LL, et al. CD69 acts downstream of interferon-alpha/beta to inhibit S1P1 and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nature. (2006) 440:540–4. 10.1038/nature04606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dixit D, Okuniewska M, Schwab SR. Secrets and lyase: control of sphingosine 1-phosphate distribution. Immunol Rev. (2019) 289:173–85. 10.1111/imr.12760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skon CN, Lee JY, Anderson KG, Masopust D, Hogquist KA, Jameson SC. Transcriptional downregulation of S1pr1 is required for the establishment of resident memory CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol. (2013) 14:1285–93. 10.1038/ni.2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pauls K, Schön M, Kubitza RC, Homey B, Wiesenborn A, Lehmann P, et al. Role of integrin alphaE(CD103)beta7 for tissue-specific epidermal localization of CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Invest Dermatol. (2001) 117:569–75. 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01481.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Conrad C, Boyman O, Tonel G, Tun-Kyi A, Laggner U, de Fougerolles A, et al. Alpha1beta1 integrin is crucial for accumulation of epidermal T cells and the development of psoriasis. Nat Med. (2007) 13:836–42. 10.1038/nm1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bromley SK, Akbaba H, Mani V, Mora-Buch R, Chasse AY, Sama A, et al. CD49a regulates cutaneous resident memory CD8+ T Cell persistence and response. CellReports. (2020) 32:108085. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gibbons DL, Abeler-Dörner L, Raine T, Hwang IY, Jandke A, Wencker M, et al. Cutting edge: regulator of G protein signaling-1 selectively regulates gut T cell trafficking and colitic potential. J Immunol. (2011) 187:2067–71. 10.4049/jimmunol.1100833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mackay LK, Kallies A. Transcriptional regulation of tissue-resident lymphocytes. Trends Immunol. (2017) 38:94–103. 10.1016/j.it.2016.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kehrl JH. The impact of RGS and other G-protein regulatory proteins on Gαi-mediated signaling in immunity. Biochem Pharmacol. (2016) 114:40–52. 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moalli F, Ficht X, Germann P, Vladymyrov M, Stolp B, de Vries I, et al. The Rho regulator Myosin IXb enables nonlymphoid tissue seeding of protective CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. (2018) 215:1869–90. 10.1084/jem.20170896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee SH. Intestinal permeability regulation by tight junction: implication on inflammatory bowel diseases. Intest Res. (2015) 13:11–8. 10.5217/ir.2015.13.1.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brandner JM, Zorn-Kruppa M, Yoshida T, Moll I, Beck LA, De Benedetto A. Epidermal tight junctions in health and disease. Tissue Barriers. (2015) 3:e974451–14. 10.4161/21688370.2014.974451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ariotti S, Beltman JB, Chodaczek G, Hoekstra ME, van Beek AE, Gomez-Eerland R, et al. Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells continuously patrol skin epithelia to quickly recognize local antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2012) 109:19739–44. 10.1073/pnas.1208927109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zaid A, Mackay LK, Rahimpour A, Braun A, Veldhoen M, Carbone FR, et al. Persistence of skin-resident memory T cells within an epidermal niche. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2014) 111:5307–12. 10.1073/pnas.1322292111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dijkgraaf FE, Matos TR, Hoogenboezem M, Toebes M, Vredevoogd DW, Mertz M, et al. Tissue patrol by resident memory CD8+ T cells in human skin. Nat Immunol. (2019) 20:756–64. 10.1038/s41590-019-0404-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McCully ML, Kouzeli A, Moser B. Peripheral tissue chemokines: homeostatic control of immune surveillance T cells. Trends Immunol. (2018) 39:734–47. 10.1016/j.it.2018.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Uderhardt S, Martins AJ, Tsang JS, Lämmermann T, Germain RN. Resident macrophages cloak tissue microlesions to prevent neutrophil-driven inflammatory damage. Cell. (2019) 177:541–55.e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reilly EC, Lambert-Emo K, Buckley PM, Reilly NS, Smith I, Chaves FA, et al. TRM integrins CD103 and CD49a differentially support adherence and motility after resolution of influenza virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2020) 117:12306–14. 10.1073/pnas.1915681117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Takesono A, Heasman SJ, Wojciak-Stothard B, Garg R, Ridley AJ. Microtubules regulate migratory polarity through Rho/ROCK signaling in T cells. PLoS ONE. (2010) 5:e8774. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kopf A, Renkawitz J, Hauschild R, Girkontaite I, Tedford K, Merrin J, et al. Microtubules control cellular shape and coherence in amoeboid migrating cells. J Cell Biol. (2020) 219:e201907154. 10.1083/jcb.201907154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pascutti MF, Geerman S, Collins N, Brasser G, Nota B, Stark R, et al. Peripheral and systemic antigens elicit an expandable pool of resident memory CD8+ T cells in the bone marrow. Eur J Immunol. (2019) 49:853–72. 10.1002/eji.201848003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pallett LJ, Burton AR, Amin OE, Rodriguez-Tajes S, Patel AA, Zakeri N, et al. Longevity and replenishment of human liver-resident memory T cells and mononuclear phagocytes. J Exp Med. (2020) 217:e20200050. 10.1084/jem.20200050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Clark GF, Schust DJ. Manifestations of immune tolerance in the human female reproductive tract. Front Immun. (2013) 4:26. 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhao S, Zhu W, Xue S, Han D. Testicular defense systems: immune privilege and innate immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. (2014) 11:428–37. 10.1038/cmi.2014.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Charras G, Sahai E. Physical influences of the extracellular environment on cell migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2014) 15:813–24. 10.1038/nrm3897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moreau HD, Piel M, Voituriez R, Lennon-Duménil AM. Integrating physical and molecular insights on immune cell migration. Trends Immunol. (2018) 39:632–43. 10.1016/j.it.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thom JT, Weber TC, Walton SM, Torti N, Oxenius A. The salivary gland acts as a sink for tissue-resident memory CD8(+) T cells, facilitating protection from local cytomegalovirus infection. Cell Rep. (2015) 13:1125–36. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smith CJ, Caldeira-Dantas S, Turula H, Snyder CM. Murine CMV Infection induces the continuous production of mucosal resident T cells. Cell Rep. (2015) 13:1137–48. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stolp B, Thelen F, Ficht X, Altenburger LM, Ruef N, Inavalli VVGK, et al. Salivary gland macrophages and tissue-resident CD8+ T cells cooperate for homeostatic organ surveillance. Sci Immunol. (2020) 5:eaaz4371. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz4371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Paluch EK, Aspalter IM, Sixt M. Focal adhesion-independent cell migration. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. (2016) 32:469–90. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-111315-125341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Overstreet MG, Gaylo A, Angermann BR, Hughson A, Hyun YM, Lambert K, et al. Inflammation-induced interstitial migration of effector CD4? T cells is dependent on integrin αV. Nat Immunol. (2013) 14:949–58. 10.1038/ni.2682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bergert M, Erzberger A, Desai RA, Aspalter IM, Oates AC, Charras G, et al. Force transmission during adhesion-independent migration. Nat Cell Biol. (2015) 17:524–9. 10.1038/ncb3134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sahai E, Marshall CJ. Differing modes of tumour cell invasion have distinct requirements for Rho/ROCK signalling and extracellular proteolysis. Nat Cell Biol. (2003) 5:711–19. 10.1038/ncb1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Reversat A, Gaertner F, Merrin J, Stopp J, Tasciyan S, Aguilera J, et al. Cellular locomotion using environmental topography. Nature. (2020) 582:582–5. 10.1038/s41586-020-2283-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gebhardt T, Whitney PG, Zaid A, Mackay LK, Brooks AG, Heath WR, et al. Different patterns of peripheral migration by memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Nature. (2011) 477:216–9. 10.1038/nature10339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rowe RG, Weiss SJ. Breaching the basement membrane: who, when and how? Trends Cell Biol. (2008) 18:560–74. 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sorokin L. The impact of the extracellular matrix on inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. (2010) 10:712–23. 10.1038/nri2852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Huber AR, Weiss SJ. Disruption of the subendothelial basement membrane during neutrophil diapedesis in an in vitro construct of a blood vessel wall. J Clin Invest. (1989) 83:1122–36. 10.1172/JCI113992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wolf K. Amoeboid shape change and contact guidance: T-lymphocyte crawling through fibrillar collagen is independent of matrix remodeling by MMPs and other proteases. Blood. (2003) 102:3262–9. 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Halle S, Keyser KA, Stahl FR, Busche A, Marquardt A, Zheng X, et al. In vivo killing capacity of cytotoxic T cells is limited and involves dynamic interactions and T cell cooperativity. Immunity. (2016) 44:233–45. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lomakin AJ, Cattin CJ, Cuvelier D, Alraies Z, Molina M, Nader GPF, et al. The nucleus acts as a ruler tailoring cell responses to spatial constraints. Science. (2020) 370:eaba2894. 10.1126/science.aba2894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Venturini V, Pezzano F, Català Castro F, Häkkinen HM, Jiménez-Delgado S, Colomer-Rosell M, et al. The nucleus measures shape changes for cellular proprioception to control dynamic cell behavior. Science. (2020) 370:eaba2644. 10.1126/science.aba2644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schenkel JM, Fraser KA, Masopust D. Cutting edge: resident memory CD8 T cells occupy frontline niches in secondary lymphoid organs. J Immunol. (2014) 192:2961–4. 10.4049/jimmunol.1400003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sung JH, Zhang H, Moseman EA, Alvarez D, Iannacone M, Henrickson SE, et al. chemokine guidance of central memory T cells is critical for antiviral recall responses in lymph nodes. Cell. (2012) 150:1249–63. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kumar BV, Ma W, Miron M, Granot T, Guyer RS, Carpenter DJ, et al. Human tissue-resident memory T cells are defined by core transcriptional and functional signatures in lymphoid and mucosal sites. Cell Rep. (2017) 20:2921–34. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pfeiffer F, Kumar V, Butz S, Vestweber D, Imhof BA, Stein JV, et al. Distinct molecular composition of blood and lymphatic vascular endothelial cell junctions establishes specific functional barriers within the peripheral lymph node. Eur J Immunol. (2008) 38:2142–55. 10.1002/eji.200838140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.