Abstract

Meningitis remains a rare but potentially life-threatening intracranial complication of acute rhinosinusitis.

We describe a case of a 62-year-old man with a background of chronic rhinosinusitis who presented to hospital with confusion, fever and bilateral green purulent rhinorrhoea. After immediate sepsis management, urgent contrast-enhanced computed tomography head revealed opacification of all paranasal sinuses and bony erosion of the lateral walls of both ethmoid sinuses. He was treated with intravenous antibiotics, topical nasal steroids, decongestants and irrigation. Following a turbid lumbar puncture and multidisciplinary discussion, he was admitted to the critical care unit and later intubated due to further neurological deterioration. After 13 days admission and rehabilitation in the community he made a good recovery.

This case highlights the importance of timely diagnosis and appropriate management of acute rhinosinusitis and awareness of the possible complications. Joint care with physicians and intensivists is crucial in the management of these sick patients.

Keywords: rhinosinusitis, meningitis, intracranial complication, critical care, Streptococcus pneumoniae

Background

Leonardo da Vinci was the first to produce detailed drawings of the paranasal sinuses in 1489. Drake and Cowper were among the first to report cases of halitosis caused by maxillary sinus suppuration in 1707, which they successfully treated with dental extraction and opening of the maxillary sinus via the alveolus.1 Today, rhinosinusitis is recognised as a common condition in most parts of the world, affecting the majority of individuals at some point in their lifetime. Both acute rhinosinusitis (ARS) and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) cause a significant burden on society both in terms of healthcare consumption and productivity loss.2,3 ARS has a one-year prevalence of 6–15% and CRS is thought to affect 5–12% of the general population.3,4 A case-control study investigating the socioeconomic costs of CRS in the UK reported an additional £2,419 spent per annum on costs for primary and secondary care compared to the control group and a total of 18.7 missed work days per patient per year.5

The term ‘rhinosinusitis’, first introduced in the 1990s, describes inflammation of the nasal mucosa and paranasal sinuses and recognises that their linings are in continuity.3 According to the European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps, CRS with or without nasal polyps in adults is defined clinically by the presence of two or more symptoms lasting more than 12 weeks. One of the symptoms should be either nasal blockage, obstruction, congestion or discharge with other possible symptoms including facial pain and a reduction in the sense of smell.

ARS has similar diagnostic criteria to CRS but with symptoms lasting less than 12 weeks.2 ARS usually has an infective aetiology (viral, bacterial, fungal) and can be divided into viral ARS, post-viral ARS and bacterial ARS. Viral ARS, also known as the ‘common cold’, represents the majority of cases and is usually self-limiting lasting less than 10 days. Post-viral ARS is characterised by an increase in symptoms after 5 days (double sickening) or symptoms that last more than 10 days and represents a perpetuation of the inflammatory response after the virus has been cleared.6 Only a small proportion of ARS is from bacterial origin and is diagnosed when three of the following symptoms/signs are present: discoloured mucus, severe local pain, temperature above 38 °C, raised C-reactive protein (CRP)/erythrocyte sedimentation rate or double sickening.3 Since the introduction and widespread use of antibiotic therapy, the complications of ARS have thankfully become rare but are still an important cause of substantial morbidity and occasional mortality.3,6 It is, therefore, important for clinicians to be familiar with this disease entity and its timely investigation and management.

We report a case of fulminant meningitis in an adult secondary to superimposed bacterial ARS.

Case Presentation

A 62-year-old man was brought to the emergency department by ambulance, having been found unresponsive in bed. His wife reported a 5-day history of bilateral otalgia, not improved by the use of olive oil ear drops for presumed impacted ear wax. His Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score at the scene was reported by the ambulance crew to be 8 (E = 2, V = 1, M = 5).

His past medical history included CRS with nasal polyposis for which he previously underwent functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) with nasal polypectomy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, glaucoma, right sided keratoconus treated with a previous corneal graft and hypercholesterolaemia. His regular medications included a beclomethasone/formoterol inhaler, salbutamol inhaler, amlodipine, simvastatin and beclometasone dipropionate nasal spray.

On examination, the patient was tachypnoeic (25 breaths per minute), tachycardic (120 beats per minute) and pyrexial (40°C). His GCS was 11 (E = 4, V = 1, M = 6). He had bilateral green purulent rhinorrhea, bilateral proptosis and right sided chemosis. Flexible nasendoscopy (FNE) was made difficult due to thick green secretions streaming from the middle meatuses bilaterally.

Investigations

Laboratory tests revealed raised CRP (335 mg/L; reference range <10 mg/L), raised white cell count (24.7 × 109/L; reference range 4.0–11.0 × 109/L), raised neutrophil count (22.2 × 109/L; reference range 1.8–7.70), low lymphocyte count (0.5 × 109/L; reference range 1.4–4.8) and raised lactate (2.8 mmol/L; reference range 0.6–1.4). Pus aspirates collected from both nasal cavities during FNE were sent for microscopy, culture and sensitivity testing. Streptococcus pneumoniae was isolated from both samples. There was no evidence of fungal infection.

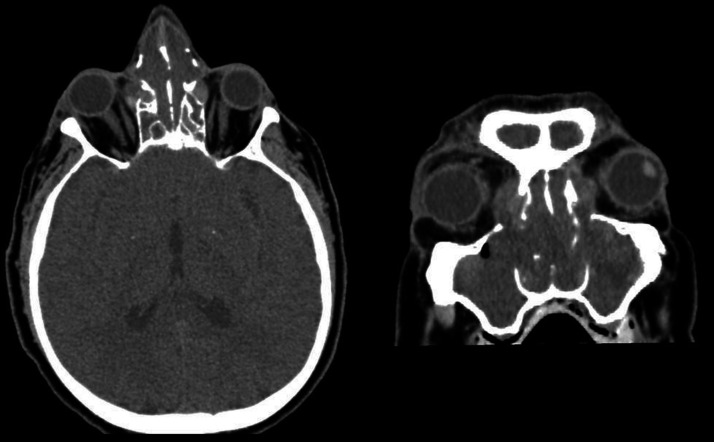

The patient was taken for contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the head and sinuses within his first hour of presentation to the hospital. It demonstrated opacification of the paranasal sinuses, bony erosion of the lateral walls of both ethmoid sinuses with a small amount of soft tissue bulging into the right orbit, bilateral proptosis, but no intracranial abnormality (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Axial and coronal sections from contrast-enhanced CT of head (bone window) demonstrating opacification of the ethmoid sinuses, bony erosion of the lateral wall of both ethmoids with a small amount of soft tissue bulging into the right orbit.

The patient became increasingly combative, confused and had aversion to light. A lumbar puncture was performed which revealed pale cloudy fluid macroscopically and an extremely cellular specimen composed mainly of neutrophils. Protein was high (4.07 g/L; reference range 0.15–0.45 g/L) and glucose was low (<0.5 mmol/L; reference range 2.2–4.0). Streptococcus pneumoniae was isolated with no evidence of fungal infection.

Treatment

Treatment for sepsis and presumed meningitis was initiated in the emergency department. The patient was started on intravenous ceftriaxone, fluticasone nasal spray, xylometazoline hydrochloride nasal spray and regular saline nasal irrigation.

The patient was admitted to the critical care unit (CCU) under joint care of the ear nose and throat (ENT), medical and critical care teams. On the evening of admission, due to worsening neurological symptoms including agitation, he was intubated and ventilated.

The patient was successfully extubated after 8 days and completed a 10-day course of intravenous antibiotics. He was discharged home 13 days after admission with ongoing input from the physiotherapy and occupational therapy teams due to the physical deconditioning experienced as a result of being sedated and ventilated. Outpatient follow-up with the critical care and ENT teams was also arranged and he was prescribed a 2-week course of betamethasone nasal drops followed by a 6-week course of fluticasone nasal spray with regular saline nasal irrigation throughout.

Outcome and Follow-Up

At 3-month follow-up the patient was recovering well and had returned to work full time. He reported some vivid memories of his stay on CCU but did not display any signs of post-traumatic stress disorder. He continued to be managed medically as an outpatient by the ENT team for his ongoing CRS with nasal polyposis as he did not wish for further sinus surgery.

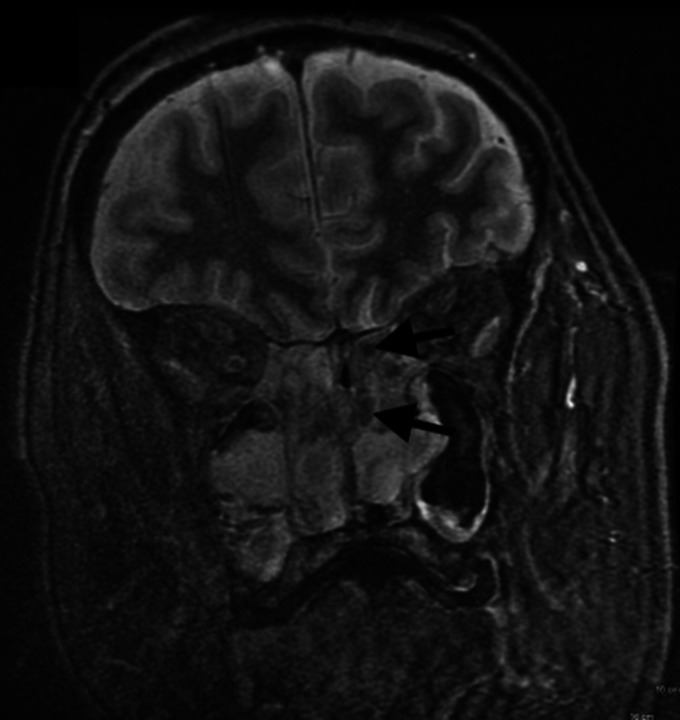

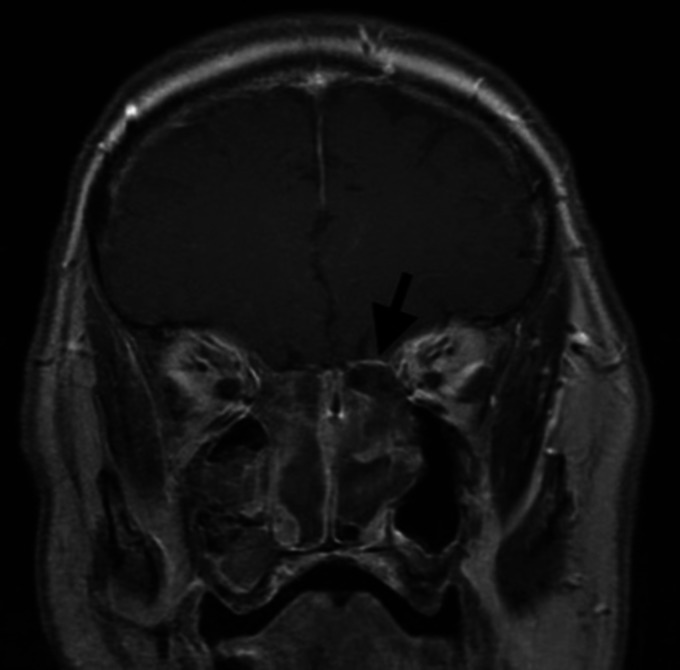

6-month follow-up contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, orbits and postnasal space revealed extensive bilateral ethmoid polyposis extending into the maxillary sinuses and preseptal space of the right orbit, hypertrophied inferior turbinates projecting into and obliterating the postnasal space and left sided smooth dural enhancement indicative of meningeal inflammation (Figures 2 and 3). Aspergillus and Alternaria specific IgE levels were within normal range.

Figure 2.

Coronal section from contrast-enhanced fat suppressed MRI of brain, orbits and postnasal space demonstrating bilateral ethmoid polyposis.

Figure 3.

Coronal section from contrast-enhanced T1 weighted MRI of brain, orbits and postnasal space demonstrating left sided smooth dural enhancement indicative of meningeal inflammation.

Discussion

Viral ARS is caused by infection of the nasal epithelium, most commonly by a rhinovirus or coronavirus. This triggers an inflammatory cascade causing oedema, engorgement, fluid extravasation, mucus production and sinus obstruction which can eventually lead to post-viral ARS and in some cases super-imposed bacterial infection. The most frequently isolated organisms in bacterial ARS are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Hemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis.3,7 The complications of ARS and CRS are typically classified as orbital (60–80%), intracranial (15–20%) or osseous (5%). In the literature, males are more frequently affected than females, bacterial ARS is more often a precipitating factor in children, whereas CRS has a greater association in adults.8 Since complications of ARS and CRS are rare, there are currently no accurate prevalence data for the UK. However, the incidence of bacterial ARS complications worldwide is estimated at three cases per million of the population per year.8

The intracranial complications of bacterial ARS can occur at any age, with a preponderance of young adults in their second decade. They include meningitis, epidural empyema, subdural empyema, cerebritis, brain abscess, superior sagittal and cavernous sinus thrombosis and are usually associated with frontoethmoidal or sphenoid bacterial ARS.3 There are two routes by which infection can spread. The first involves retrograde spread via the formation of a thrombus or release of septic emboli, which pass through the valve-less diploic veins to reach the brain. The second is through direct extension of disease, via erosion of the thin osseous sinus walls, congenital or traumatic defects, or existing foramina.2 Once infection has gained access to the brain, the resulting inflammation causes cerebritis which can progress to necrosis and liquefaction of the brain parenchyma and eventually lead to a reactive connective tissue capsule forming around a brain abscess.3

Osseous complications are the result of bacterial infection affecting the bony sinus walls causing osteomyelitis and a subperiosteal abscess which can eventually involve the brain and nervous system.3 Pott’s puffy tumour is an example of this affecting the anterior table of the frontal sinus and presenting as a tender swelling on the forehead of a patient.8

A systemic review of paediatric intracranial complications of sinusitis by Patel et al. identified 180 patients in the literature and reported the most common complication to be subdural empyema (49%), with meningitis being responsible for only 10% of cases.9 A UK retrospective review of 47 patients admitted with intracranial complications secondary to rhinosinusitis identified only one patient with meningitis (2%).10 There is a great deal of overlap between the presenting symptoms of the different intracranial complications. The majority of patients present with specific signs or symptoms suggestive of intracranial inflammatory involvement such as nausea and vomiting, neck stiffness, seizures, a focal neurological deficit, or as in our case altered mental state.2,3

Contrast-enhanced CT is typically the imaging modality chosen to diagnose intracranial complications due to availability, ease of use and clear definition of bony structures. However, MRI may be beneficial when reviewing soft tissue changes and lacks ionizing radiation.8 In cases where meningitis is suspected, and a space-occupying lesion has been excluded, lumbar puncture is performed to better guide antimicrobial therapy. Streptococcus (grown in our case) and Staphylococcus species including methicillin-resistant (MRSA) and anaerobes are the organisms most commonly isolated.3

Targeted high dose intravenous antimicrobial therapy is the mainstay of treatment for the intracranial complications of ARS.11 Neurosurgical intervention is indicated to relieve symptomatic intracranial mass effect. If there is failure to improve on medical therapy, progression of disease or deterioration of symptoms then FESS should be considered.2 As in our case, the critical care team should be involved early in patients with bacterial meningitis and risk factors for poor outcome should be reviewed regularly. These include reduced GCS, haemodynamic instability, persistent seizures and hypoxia.12 Ancillary treatments are designed to promote ciliary function and decrease oedema to improve paranasal sinus drainage and include intranasal topical steroids, decongestants and nasal irrigation. Although the evidence supporting the use of ancillary treatments is relatively weak, most ENT surgeons would include these in their management plan and indeed these were prescribed in our case.7

In conclusion, ARS is usually a self-limiting disease. However, rarely it can lead to potentially life-threatening complications. Timely diagnosis and appropriate management of disease and possible complications are key to reducing the long-term sequelae in these patients.

Learning Points

ARS and CRS are common conditions in most parts of the world and represent a significant burden on society both in terms of healthcare consumption and productivity loss.

Since the introduction and widespread use of antibiotic therapy, the complications of ARS and CRS have become rare but are still an important cause of substantial morbidity and occasional mortality.

The complications of ARS and CRS are the result of direct extension of disease or haematological spread of superimposed bacterial or fungal infection and are typically classified as orbital (60–80%), intracranial (15–20%) or osseous (5%).

Rarely, ARS and CRS can lead to serious and potentially life-threatening complications.

Acknowledgments

The author(s) would like to thank Dr Philip Murray Consultant Radiologist for his assistance with manuscript preparation.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent: Written informed consent for patient information and images to be published was provided by the patient and a copy of the written consent is available for review on request.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

ORCID iD: Stephen Bennett https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9488-0114

References

- 1.Nogueira JF, Jr, Hermann DR, Américo Rdos R, et al. A brief history of otorhinolaryngolgy: otology, laryngology and rhinology. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2007; 73(5):693–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziegler A, Patadia M, Stankiewicz J. Neurological complications of acute and chronic sinusitis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018; 18(2):5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Hopkins C, et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2020. Rhinology. 2020; 58(Suppl S29):1–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stjärne P, Odebäck P, Ställberg B, et al. High costs and burden of illness in acute rhinosinusitis: real-life treatment patterns and outcomes in swedish primary care. Prim Care Respir J. 2012; 21(2):174–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wahid NW, Smith R, Clark A, et al. The socioeconomic cost of chronic rhinosinusitis study. Rhinology. 2020; 58(2):112–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaume F, Quintó L, Alobid I, et al. Overuse of diagnostic tools and medications in acute rhinosinusitis in Spain: a population-based study (the PROSINUS study). BMJ Open. 2018; 8(1):e018788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masood A, Moumoulidis I, Panesar J. Acute rhinosinusitis in adults: an update on current management. Postgrad Med J. 2007; 83(980):402–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carr TF. Complications of sinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2016; 30(4):241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel NA, Garber D, Hu S, et al. Systematic review and case report: intracranial complications of pediatric sinusitis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016; 86:200–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones NS, Walker JL, Bassi S, et al. The intracranial complications of rhinosinusitis: can they be prevented? Laryngoscope. 2002; 112(1):59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicoli TK, Oinas M, Niemelä M, et al. Intracranial suppurative complications of sinusitis. Scand J Surg. 2016; 105(4):254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGill F, Heyderman R, Michael B, et al. The UK Joint Specialist Societies Guideline on the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Meningitis and Meningococcal Sepsis in Immunocompetent Adults. J Infect 2016;72(4):405–38. [DOI] [PubMed]