Summary

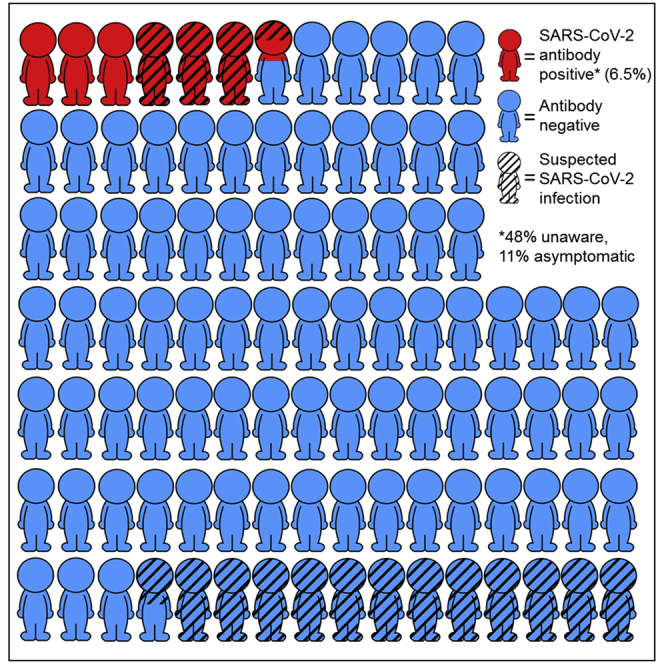

Awareness of infection with SARS-CoV-2 is crucial for the effectiveness of COVID-19 control measures. Here, we investigate awareness of infection and symptoms in relation to antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in healthy plasma donors. We asked individuals donating plasma across the Netherlands between May 11th and 18th 2020 to report COVID-19-related symptoms, and we tested for antibodies indicative of a past infection with SARS-CoV-2. Among 3,676 with antibodies, and from questionnaire data, 239 (6.5%) are positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Of those, 48% suspect no COVID-19, despite the majority reporting symptoms; 11% of seropositive individuals report no symptoms and 27% very mild symptoms at any time during the first peak of the epidemic. Anosmia/ageusia and fever are most strongly associated with seropositivity. Almost half of seropositive individuals do not suspect SARS-CoV-2 infection. Improved recognition of COVID-19 symptoms, in particular, anosmia/ageusia and fever, is needed to reduce widespread SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, infection awareness, plasma donation, antibodies, symptoms, anosmia

Graphical abstract

Highlights

SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing in healthy donors reveals a low awareness of past infection

48% of SARS-CoV-2 seropositive individuals do not suspect infection

11% of SARS-CoV-2 seropositive individuals report no and 27% only very mild symptoms

Anosmia/ageusia is 12.7 times more common in seropositive individuals

Van den Hurk et al. investigate awareness of SARS-CoV-2 infection and symptoms in relation to antibody status in healthy plasma donors. Forty-eight percent of seropositive individuals do not suspect SARS-CoV-2 infection, and 11% are asymptomatic. Improved recognition of COVID-19 symptoms, in particular anosmia/ageusia and fever, is needed to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Introduction

Due to the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), governments worldwide are struggling to find an appropriate balance between virus control measures and their societal and economic consequences.1 Physical distancing and (partial) closures of offices, nursing homes, restaurants, schools, and shops have played—and still play—an important role in combating the spread of SARS-CoV-2. An impending economic crisis and the huge societal burden call for informed easing of these measures.

Limited knowledge exists regarding the extent to which SARS-CoV-2 infections may remain undetected, while pre- and asymptomatic individuals are thought to contribute significantly to the spread of SARS-CoV-2.2,3 A wide clinical spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 infections has been described, ranging from mild flu-like symptoms to severe viral pneumonia with respiratory failure and death.4,5 Due to the limited availability of tests and infrastructure, more severe COVID-19 cases are likely overrepresented in the majority of studies conducted thus far. Many cases may remain undetected in the event of asymptomatic infection, mild infection with isolated symptoms such as the loss of taste and/or smell (anosmia/ageusia), or symptomatic infections that are attributed to other causes.3,6,7

Post-lockdown measures often rely on individuals, in particular those who have been in contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case, to self-isolate and be tested in the event of COVID-19-related symptoms. These measures are dependent on individuals’ recognition of symptoms, yet it is unknown whether infected individuals are able to identify themselves as such. Hence, we studied the association between COVID-19 suspicion and SARS-CoV-2 antibody status, as well as that between self-reported symptoms and antibody status in healthy adults.

Results

Of the 8,275 donors who underwent plasmapheresis between the 11th and 18th of May 2020, we tested 7,150 for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, 419 (5.9%) of whom tested positive. The optical density:cutoff (OD:CO) ratio in seropositive individuals ranged from 1.01 to 20.86. We invited 7,721 individuals to participate in the online questionnaire, 4,275 (55.4%) of whom participated. Antibody and questionnaire data were complete for 3,676 individuals, including 239 (6.5%) who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Seropositive individuals were generally younger and more likely to live in the southern region of the Netherlands than seronegative individuals (Table 1). Forty-eight percent of the seropositive individuals and 87% of the seronegative, did not suspect they had had COVID-19. Approximately 11% of the seropositive individuals reported no symptoms at all and 73% reported symptoms indicative of COVID-19. An additional 27% of seropositive individuals reported only very mild symptoms, generally sneezing (69%), coryza (55%), and/or fatigue (40%). Only one individual positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies was admitted to a hospital, but this was because of gastrointestinal complaints. The median date of symptom onset in seropositive individuals was March 15, 2020. Symptom onset was between March 6 and 28 in 50% of the seropositive individuals.

Table 1.

Characteristics and COVID-19 status, stratified by SARS-CoV-2 antibody status

| SARS-CoV-2 antibody positive | SARS-CoV-2 antibody negative | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 239 | 3,437 | |

| Gender (%) | |||

| Male | 126 (52.7) | 1,766 (51.4) | 0.696 |

| Female | 113 (47.3) | 1,671 (48.6) | |

| Age, y | 46.6 ± 13.8 | 50.0 ± 14.0 | <0.001 |

| Region (%)a | |||

| South | 98 (41) | 943 (27) | <0.001 |

| Mid | 114 (48) | 1,846 (54) | |

| North | 27 (11) | 641 (19) | |

| COVID-19 status (%) | |||

| Infection diagnosedb | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Infection suspected | 125 (52.3) | 435 (12.7) | |

| Infection not suspected | 114 (47.7) | 3,002 (87.3) | |

| Symptom severity (%) | |||

| Asymptomatic | 26 (10.9) | 1,047 (30.5) | <0.001 |

| Only very mild symptoms | 64 (26.8) | 1,250 (36.4) | |

| Mild to severe symptoms | 149 (62.3) | 1,134 (33.0) | |

| Clinically suspected COVID-19 (%)c | 174 (72.8%) | 1,349 (39.2%) | <0.001 |

| Contacted physician (%) | 30 (12.6) | 270 (7.9) | 0.009 |

| Admitted to hospital (%) | 1 (0.4) | 14 (0.4) | 0.980 |

| Symptom onset (2020)d | 15.03 (06.03–28.03) | 10.03 (21.02–01.04) | |

Numbers (percentage within antibody status) and means ± standard deviations are shown. p values indicate the significance of differences; a 2-sided t test for age, χ2 tests for proportions.

North = provinces of Friesland, Groningen, Drenthe, and Overijssel; South = North Brabant, Limburg, and Zeeland; Mid = all other provinces.

Self-reported PCR-confirmed diagnoses.

According to clinical criteria of WHO COVID-19 Case Definition (see Method details).

Date of symptom (DD.MM) onset in the year 2020, median (interquartile range).

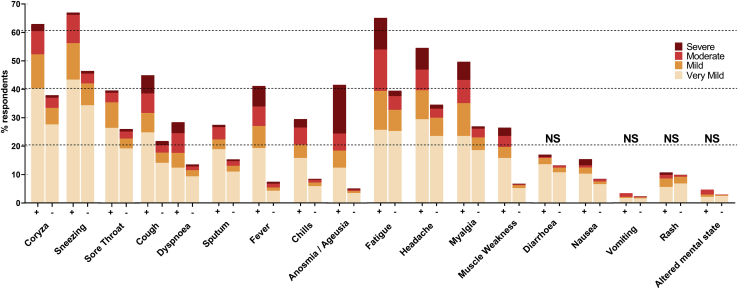

Apart from diarrhea, vomiting, rash, and an altered mental state (confusion), all of the symptoms were significantly more frequently reported by seropositive versus seronegative individuals (Figure 1). Anosmia/ageusia was the symptom most strongly associated with the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies; the odds ratio of 12.7 was significantly higher than for any other COVID-19-related symptom (Table 2). Despite this strong association, it was not the most prevalent symptom among seropositive individuals. Other symptoms such as fever, coryza, fatigue, cough, headache, myalgia, and sneezing were similarly or even more prevalent among these individuals. However, these symptoms appeared less indicative of a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Figure 1.

Prevalence and severity of symptoms by antibody status: positive (+) or negative (−)

Age- and gender-adjusted logistic regression models indicate higher prevalence in 239 antibody-positive versus 3,437 antibody-negative individuals for all symptoms (p < 0.001; Table 2), except where indicated as not significant (NS). Samples that tested reactive for antibodies, including samples with weak reactivity (OD:CO ratio ³ 0.5), were re-tested and considered positive if the re-test was reactive (OD:CO ratio > 1.0).

Table 2.

Associations between COVID-19 suspicion, symptom severity, and symptoms with SARS-CoV-2 antibody positivity and high levels of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies

| OR (95% CI) for SARS-CoV-2 antibody positivity n = 3,676 | OR (95% CI)a for high levels of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies n = 239 | |

|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 status: infection diagnosed or suspected | 7.29 (5.52–9.63)∗ | 3.90 (2.16–7.06)∗ |

| Symptom severityb | ||

| Only very mild symptoms | 2.06 (1.30–3.28)∗ | 2.65 (1.03–6.80)∗ |

| Mild to severe symptoms | 5.16 (3.34–7.96)∗ | 4.35 (1.79–10.62)∗ |

| Clinically suspected COVID-19c | 4.06 (3.00–5.50)∗ | 4.61 (2.46–8.67)∗ |

| Contacted physician | 1.75 (1.16–2.64)∗ | 1.06 (0.47–2.42) |

| COVID-19 symptoms | ||

| Coryza | 2.60 (1.98–3.42)∗ | 2.45 (1.39–4.31)∗ |

| Sneezing | 2.16 (1.63–2.86)∗ | 1.32 (0.75–2.34) |

| Sore throat | 1.77 (1.34–2.34)∗ | 3.36 (1.79–6.30)∗ |

| Cough | 2.81 (2.15–3.69)∗ | 2.16 (1.22–3.84)∗ |

| Dyspnea | 2.44 (1.80–3.30)∗ | 4.80 (2.20–10.46)∗ |

| Sputum production | 2.02 (1.49–2.73)∗ | 2.25 (1.15–4.40)∗ |

| Fever | 8.27 (6.18–11.08)∗ | 2.92 (1.59–5.35)∗ |

| Chills | 4.29 (3.14–5.85)∗ | 2.95 (1.48–5.87)∗ |

| Anosmia/ageusia | 12.74 (9.41–17.23)∗ | 3.91 (2.08–7.35)∗ |

| Fatigue | 2.70 (2.03–3.59)∗ | 2.94 (1.60–5.41)∗ |

| Headache | 2.19 (1.65–2.89)∗ | 2.57 (1.41–4.66)∗ |

| Myalgia | 2.58 (1.98–3.37)∗ | 1.97 (1.12–3.44)∗ |

| Muscle weakness | 4.70 (3.40–6.49)∗ | 4.80 (2.14–10.77)∗ |

| Diarrhea | 1.21 (0.84–1.73) | 1.71 (0.78–3.72) |

| Nausea | 1.84 (1.25–2.71)∗ | 1.25 (0.57–2.74) |

| Vomiting | 1.34 (0.64–2.82) | 4.10 (0.49–34.26) |

| Rash | 1.04 (0.68–1.60) | 0.89 (0.37–2.13) |

| Altered mental status | 1.47 (0.78–2.80) | 6.34 (0.78–51.15) |

∗ indicates statistical significance. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Associations with antibody levels (OD:CO > 10, n = 159) are only assessed in individuals who are positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

Asymptomatic = reference.

According to clinical criteria of WHO COVID-19 Case Definition (see Method details). Age- and gender-adjusted ORs and 95% CIs are shown.

In seropositive individuals, the presence of symptoms was also significantly associated with high levels of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, except for the symptoms of sneezing and nausea (Table 2). Dyspnea and muscle weakness were most strongly associated with high levels of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Individuals who suspected that they had a SARS-CoV-2 infection were significantly more likely to be SARS-CoV-2 antibody positive and, among those antibody-positive individuals, to have high levels of antibodies compared to individuals who did not suspect having had COVID-19. More severe symptoms versus being asymptomatic were also associated with antibody status and levels, as was consultation of a physician because of those symptoms.

Of all of the individuals who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, those who did not suspect having had the infection reported no or very mild symptoms in 19% and 41% of all cases, compared to only 3% and 14%, respectively, of those who did suspect having had COVID-19 (Table 3). Physician contact and hospital admittance did not differ between antibody-positive individuals who did or did not suspect having had COVID-19. Individuals who did not suspect having had COVID-19 attributed their symptoms to unrelated circumstances, such as allergies, in 39% of the cases, or temporary illness such as the flu, unknown reasons, or chronic complaints in 20%, 18%, and 4% of the cases, respectively. Among the 45 individuals who did not suspect COVID-19 in spite of mild to severe symptoms, 5 reported a negative PCR test (tests were done 3–52 days after symptom onset). Nine individuals had non-specific symptoms (e.g., coryza, sneezing). Another 31 individuals had symptoms indicative of COVID-19 according to the World Health Organization (WHO) Case Definition, but attributed those to unrelated circumstances (e.g., hay fever, trauma, n = 17), temporary illness (e.g., flu, n = 8), chronic complaints (n = 3), or unknown reasons (n = 3). Of all of the individuals who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, those suspecting COVID-19 were significantly more likely to report more severe symptoms (76% versus 27%), or symptoms indicative of COVID-19 according to the WHO Case Definition (84% versus 33%).

Table 3.

Symptom severity, healthcare use, and suspected causes of symptoms, stratified by COVID-19 suspicion in individuals positive and negative for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies

| COVID-19 diagnosed or suspected | COVID-19 not suspected | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies | n = 125 | n = 114 | |

| Symptom severity (%) | |||

| Asymptomatic | 4 (3.2) | 22 (19.3) | <0.001 |

| Only very mild symptoms | 17 (13.6) | 47 (41.2) | |

| Mild to severe symptoms | 104 (83.2) | 45 (39.5) | |

| Clinically suspected COVID-19 (%)a | 119 (95.2) | 55 (48.2) | <0.001 |

| Contacted a physician (%) | 15 (12.0) | 15 (13.2) | 0.947 |

| Admitted to hospital | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0.477 |

| Likely cause of symptoms, if any (%) | |||

| Temporary illness | 106 (84.8) | 23 (20.1) | <0.001 |

| Chronic complaints | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.5) | |

| Unrelated circumstancesb | 5 (4.0) | 44 (38.6) | |

| Unknown | 10 (8.0) | 20 (17.5) | |

| Negative for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies | n = 435 | n = 2993 | |

| Symptom severity (%) | |||

| Asymptomatic | 31 (7.1) | 1017 (34.0) | <0.001 |

| Only very mild symptoms | 74 (17.0) | 1172 (39.2) | |

| Mild to severe symptoms | 330 (75.9) | 804 (26.9) | |

| Clinically suspected COVID-19 (%)a | 365 (83.9) | 982 (32.8) | <0.001 |

| Contacted a physician (%) | 50 (11.5) | 205 (6.8) | 0.001 |

| Admitted to hospital (%) | 1 (0.2) | 13 (0.4) | 1.000 |

Numbers (percentage within COVID-19 suspicion status) are shown; differences tested with χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test in the event of cells with expected counts <5.

According to clinical criteria of WHO COVID-19 Case Definition (see Method details).

Circumstances not related to COVID-19, such as allergies or trauma.

Discussion

We explored associations between COVID-19 suspicion and SARS-CoV-2 antibody status, as well as between symptoms and antibody status in healthy adults. Of those with reactive test results, 48% did not suspect having been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Eleven percent reported a complete absence of symptoms and 27% only very mild symptoms during the national peak of the epidemic. COVID-19-related symptoms, particularly anosmia/ageusia and fever, were significantly associated with antibody status, independent of age and gender.

The lack of COVID-19 suspicion in almost half of the subgroup that tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies may have an impact on individual adherence to governmental measures and on the decision to request a PCR test, as health behavior largely depends on beliefs regarding one’s own and others’ perceived susceptibility to and severity of disease.8 A behavioral study by the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment showed that 80% of the people who reported symptoms did not stay inside their homes and 40% even went to work.9 Also, while 68% of the study participants indicated that they will get tested if they develop symptoms, this percentage drops to 28% among individuals once they displayed symptoms. The main reason for this was that individuals attributed their symptoms to hay fever or the common cold, the latter of which may occur even more frequently during the flu season.

Assuming that the vast majority of SARS-CoV-2 infections induce an antibody response, 38% of the infected individuals reported having no (11%) or only very mild (27%) symptoms.10 An important advantage of our retrospective study design in comparison to previous studies reporting 40%–45% asymptomatic infections is the unlikelihood of falsely identifying pre-symptomatic cases as asymptomatic.3 In addition, our thorough assessment of symptoms over an extended period is likely to have captured milder symptoms that may have been underreported in previous studies. Previous studies have been mainly cross-sectional or with incomplete follow-up and with register-based symptoms rather than systematic assessments.11,12 Almost 13% of the individuals who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 did suspect a SARS-CoV-2 infection, a large majority (84%) due to symptoms indicative of COVID-19. This finding further emphasizes the non-specificity of COVID-19 symptoms, although it cannot be excluded that some of these individuals had COVID-19 without a detectable antibody response.

Particularly those individuals who reported no or very mild symptoms only were relatively unlikely to suspect having been infected with SARS-CoV-2. However, our study shows that in comparison to being asymptomatic, even very mild symptoms, and mild to severe symptoms in particular, were associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, as well as with high levels of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Our finding that anosmia/ageusia is the symptom that is most strongly associated with COVID-19 is in line with results from the COVID Symptom Study, which showed this symptom to be the strongest predictor of PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.13 Improved awareness and recognition of COVID-19 symptoms, in particular of the loss of smell and taste, may therefore help to reduce the proportion of undetected COVID-19 cases.

The strengths of this study include the large study sample, the superior performance of the Wantai SARS-CoV-2 total antibody ELISA over other antibody tests, and the thorough questionnaire-based assessment of the presence and severity of symptoms.14 As governments slowly ease virus control measures, it becomes vital to identify and isolate infected individuals to prevent new SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks.15,16 The presence of anosmia/ageusia especially should trigger PCR testing.13 In addition, our study confirms the existence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and adds that even symptomatic individuals did not suspect a SARS-CoV-2 infection. Despite the limitations of studies thus far, sufficient evidence of asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 exists.12,17 Efforts to identify cases that rely on symptoms may therefore be insufficient, which emphasizes the importance of thorough contact tracing.18

In conclusion, almost half of the individuals who tested positive for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in a high-performance immunoassay did not suspect having had an infection. This proportion may be lowered with better awareness and recognition of COVID-19 symptoms, in particular the loss of smell and taste. However, 38% of those infected reported no or only very mild symptoms. Tracing of asymptomatic contacts is therefore crucial to reduce widespread SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Limitations of study

Study participants were required to be in good health to qualify for plasma donation. This selection bias may have resulted in an underrepresentation of SARS-CoV-2 seropositive individuals and of more severe COVID-19 cases in particular. As those with more severe COVID-19 would be more likely to be aware of their past infection, this may have contributed to the high percentage of individuals unaware of their past infection. We also asked participating individuals to report their symptoms over a period of almost 3 months, which obviously introduces a risk of recall bias. Nonetheless, given the unprecedented impact of SARS-CoV-2 on society and the repeated governmental calls to self-isolate with symptoms, we expect that most individuals have an exceptional recollection of their COVID-19 suspicion and symptoms during this period.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Samples | ||

| Plasma samples from 7150 donors were tested for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies using a Wantai immunoassay. | Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise Co., Beijing, China | N/A |

| Deposited data | ||

| Dataset deposited | Open Science Framework | https://osf.io/xds75/ |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| SPSS analysis software | IBM, Armonk, U.S.A. | N/A |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Katja van den Hurk (k.vandenhurk@sanquin.nl).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

The dataset generated and analyzed in the context of this study is made available via the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/xds75/). The computer code used to generate results that are reported in this paper are available from the Lead Contact upon request.

Experimental model and subject details

The first case of COVID-19 in the Netherlands – one of the most densely populated countries in Europe with 17.2 million inhabitants (511/km2) – was reported on February 27th, 2020. By the 11th of May, 42,788 PCR-confirmed COVID-19 cases were reported, including 11,343 hospital admissions and 5,456 deaths.19 Disease prevalence showed a positive North-South gradient.

Sanquin is by law the only organization authorized to collect and distribute blood and blood components in the Netherlands. On a yearly basis, approximately 330,000 individuals aged 18 to 73 years make over 700,000 donations on a voluntary non-remunerated basis. Of those donations, 300,000 are apheresis procedures, which separate specific blood components, such as plasma, and return the remainder to the donor. Individuals must be in good health to be eligible to donate, which is checked using a pre-donation donor health questionnaire and capillary haemoglobin measurement, that are discussed in person on-site.20 Pop-ups at Sanquin’s donor website to not come in to donate in case of symptoms and the mandatory ‘COVID-19 health check’ upon entry of a donation center currently prevent individuals with any potential COVID-19-related symptoms from donating.

Individuals who donated plasma anywhere in the Netherlands between May 11th and 18th 2020 who consented (99.7%) to using leftovers of their donation for research were tested for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Those who donated COVID-19 convalescent plasma were excluded, as they were recruited separately and are, thus, not representative of regular plasma donors. Eligible individuals with registered e-mail addresses were subsequently invited to participate in an online questionnaire. This cross-sectional study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). All participating individuals gave informed consent before participating in the online questionnaire and the study protocol and procedures were approved by Sanquin’s Ethics Advisory Council and its Privacy Officer. Their gender and age are listed in Table 1. To reduce any risk of social desirability bias, we have assured individuals before taking part in the survey that their data will be treated confidentially and that all data will be coded and never traced back to the individual.

Method details

SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing

Plasma samples were tested for the presence and levels of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, using a SARS-CoV-2 total antibody ELISA (Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise Co., Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples that tested reactive, including samples with weak reactivity (OD/CO ratio ³ 0.5), were re-tested and considered positive if the re-test was reactive (OD/CO ratio > 1.0). We previously determined the sensitivity and specificity of the Wantai test to be 98.7% and 99.6%, respectively.21 As OD/CO ratios were not normally distributed, antibody levels were dichotomized (> 10.0 considered high).

Online questionnaire

Within 8 days after their donation, all individuals for whom e-mail addresses (n = 7,721) were available and valid were invited by e-mail and provided with a web link to an online questionnaire, programmed in Qualtrics (SAP, Walldorf, Germany). The questionnaire included self-reported COVID-19 status (diagnosed by PCR/suspected/not suspected) and a list of 18 symptoms considered to be COVID-19-related according guidelines specified by the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (see also ‘online questionnaire (in Dutch)’).22 Participants indicated the extent to which they suffered from these symptoms in the period between one week before the first confirmed case nationally (February 21st, 2020) and their donation date on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (severely). A symptom was considered present if the score was 1 (very mild) or higher. Symptom severity was defined as asymptomatic (score 0), only very mild symptoms (score 1) or mild to severe symptoms (score for at least one symptom 2 or higher). In accordance with the World Health Organization’s COVID-19 Case Definition, clinically suspected COVID-19 was defined based on clinical criteria. This implies that individuals who reported either anosmia/ageusia, or fever and cough, or three or more of the following symptoms: fever, cough, general weakness/fatigue, headache, myalgia, sore throat, coryza, dyspnoea, anorexia/nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, altered mental status, were considered clinically suspected COVID-19 cases.23

Participants who reported symptoms were also asked whether or not they consulted a physician or were admitted to a hospital and what they thought had caused their symptoms: temporary illness (e.g., flu, COVID-19), chronic complaints, other circumstances (e.g., allergies, trauma) or unknown.

Demographic background data on age, gender, and region were obtained from the blood bank information system eProgesa (MAK systems, Paris, France).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Descriptive information for continuous variables was calculated as mean and standard deviations, or median and interquartile range if skewed. We performed two-sided t tests for continuous variables and chi2 tests for proportions to assess differences between subgroups. Associations between symptoms and their severity with antibody status and levels were estimated using logistic regression analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, Version 23 (IBM, Armonk, U.S.A.).

Acknowledgments

The study has been funded by Sanquin Blood Supply Foundation and the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

K.v.d.H. and F.J.P. analyzed data. F.J.P., M.L.C.S., F.A.Q., S.R., and H.V. provided project support and organized participant recruitment. K.v.d.H., E.-M.M., E.S., E.M.J.H.i.V., H.L.Z., and B.M.H. designed and ran the study and wrote the manuscript. All of the authors critically revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: March 1, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100222.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Anderson R.M., Heesterbeek H., Klinkenberg D., Hollingsworth T.D. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395:931–934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park S.W., Cornforth D.M., Dushoff J., Weitz J.S. The time scale of asymptomatic transmission affects estimates of epidemic potential in the COVID-19 outbreak. Epidemics. 2020;31:100392. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2020.100392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oran D.P., Topol E.J. Prevalence of Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection : A Narrative Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;173:362–367. doi: 10.7326/M20-3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borges do Nascimento I.J., Cacic N., Abdulazeem H.M., von Groote T.C., Jayarajah U., Weerasekara I., Esfahani M.A., Civile V.T., Marusic A., Jeroncic A. Novel Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19) in Humans: A Scoping Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:E941. doi: 10.3390/jcm9040941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant M.C., Geoghegan L., Arbyn M., Mohammed Z., McGuinness L., Clarke E.L., Wade R.G. The prevalence of symptoms in 24,410 adults infected by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis of 148 studies from 9 countries. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0234765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan C.H., Faraji F., Prajapati D.P., Ostrander B.T., DeConde A.S. Self-reported olfactory loss associates with outpatient clinical course in COVID-19. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020;10:821–831. doi: 10.1002/alr.22592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poletti P., Tirani M., Cereda D., Trentini F., Guzzetta G., Sabatino G., Marziano V., Castrofino A., Grosso F., Del Castillo G. Probability of symptoms and critical disease after SARS-CoV-2 infection. arXiv. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1085. http://arxiv.org/abs/2006.08471v2 2006.08471v2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sesagiri Raamkumar A., Tan S.G., Wee H.L. Use of Health Belief Model-Based Deep Learning Classifiers for COVID-19 Social Media Content to Examine Public Perceptions of Physical Distancing: Model Development and Case Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e20493. doi: 10.2196/20493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Public Health and the Environment . in Dutch; 2020. Staying at home, testing and quarantine.https://www.rivm.nl/sites/default/files/2020-07/2020_07_14%20memo%20thuisblijven%20testen%20isoleren.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long Q.X., Liu B.Z., Deng H.J., Wu G.C., Deng K., Chen Y.K., Liao P., Qiu J.F., Lin Y., Cai X.F. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26:845–848. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gudbjartsson D.F., Helgason A., Jonsson H., Magnusson O.T., Melsted P., Norddahl G.L., Saemundsdottir J., Sigurdsson A., Sulem P., Agustsdottir A.B. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the Icelandic Population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2302–2315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2006100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavezzo E., Franchin E., Ciavarella C., Cuomo-Dannenburg G., Barzon L., Del Vecchio C., Rossi L., Manganelli R., Loregian A., Navarin N., Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team. Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team Suppression of a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in the Italian municipality of Vo’. Nature. 2020;584:425–429. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2488-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menni C., Valdes A.M., Freidin M.B., Sudre C.H., Nguyen L.H., Drew D.A., Ganesh S., Varsavsky T., Cardoso M.J., El-Sayed Moustafa J.S. Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1037–1040. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0916-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao J., Yuan Q., Wang H., Liu W., Liao X., Su Y., Wang X., Yuan J., Li T., Li J. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71:2027–2034. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kucharski A.J., Klepac P., Conlan A.J.K., Kissler S.M., Tang M.L., Fry H., Gog J.R., Edmunds W.J., CMMID COVID-19 Working Group Effectiveness of isolation, testing, contact tracing, and physical distancing on reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in different settings: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:1151–1160. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30457-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cowling B.J., Ali S.T., Ng T.W.Y., Tsang T.K., Li J.C.M., Fong M.W., Liao Q., Kwan M.Y., Lee S.L., Chiu S.S. Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e279–e288. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savvides C., Siegel R. Asymptomatic and presymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.11.20129072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandhi M., Yokoe D.S., Havlir D.V. Asymptomatic Transmission, the Achilles’ Heel of Current Strategies to Control Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2158–2160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2009758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute for Public Health and the Environment . 2020. Epidemiologische situatie COVID-19 in Nederland 11 mei 2020.https://www.rivm.nl/documenten/epidemiologische-situatie-covid-19-in-nederland-11-mei-2020 [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Committee (Partial Agreement) on Blood Transfusion (CD-P-TS) 16th ed. Council of Europe; 2020. Guide to the Preparation, Use and Quality Assurance of Blood Components. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slot E., Hogema B.M., Reusken C.B.E.M., Reimerink J.H., Molier M., Karregat J.H.M., IJlst J., Novotný V.M.J., van Lier R.A.W., Zaaijer H.L. Low SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in blood donors in the early COVID-19 epidemic in the Netherlands. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5744. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19481-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute for Public Health and the Environment . 2020. Zoek in Richtlijnen & Draaiboeken: COVID-19.https://lci.rivm.nl/richtlijnen/covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization . 2020. WHO COVID-19: Case Definitions.https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1296485/retrieve [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated and analyzed in the context of this study is made available via the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/xds75/). The computer code used to generate results that are reported in this paper are available from the Lead Contact upon request.