Abstract

Background:

In recent years, Facebook has increasingly become an essential part of the lives of people, particularly youths, thus many research efforts have been focused on investigating the potential connection between social networking and mental health issues. This study aimed to examine the relationship between Facebook use, emotional state of depression, and family satisfaction.

Methods:

This study used the online survey created in Google Docs on the Facebook ‘wall’, as research method. The survey was available during Jun–Jul 2015 in Romania. In our cross-sectional study on a sample of 708 young Facebook users (aged 13–35), we divided the sample into 3 groups: ordinary, middle, and intense Facebook users. Materials and instruments: the survey comprised a series of basic demographic as well as some measures of Facebook addiction, depression, and family satisfaction. We used two methods connected with extensive Facebook usage, the first one measuring only the intensity of use, and the second one measuring not only the intensity but also the consequences of this use.

Results:

Facebook engagement is negatively related to family satisfaction. Moreover, Facebook engagement is positively related to depression symptoms. The Pearson correlations showed that higher Facebook intensity is positively associated with Facebook addiction.

Conclusion:

The study confirm previously published findings of other authors in the fields of social networking psychology. The study examined the relationship between Facebook use, depression, and life satisfaction and the hypotheses were supported.

Keywords: Social media, Facebook, Youth, Health outcomes, Family satisfaction

Introduction

Founded in 2004, Facebook has become a global phenomenon and remains the most popular social networking site in the world. Newer social networks (e.g. Instagram, Tweeter) recently gain more popularity, but still, users tend to engage in these platforms in addition to Facebook, rather than as simple replacements (1). As of first quarter of 2017, Facebook users had reached nearly two billion users around the world where approximately 85.8% of daily active users are outside the United States of America and Canada (2). The assumed mission of Facebook is “to make the world more open and connected” allowing users staying in touch with family and friends, sharing personal matters, and finding out news around the globe.

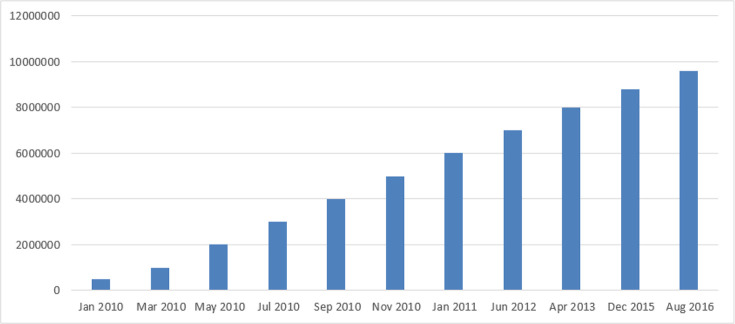

Facebook is also popular among Romanian youth. A monitoring platform of Facebook pages in Romania, the number of users had reached 9,600,000, with a penetration of 44.44% of the country’s population (3). The number of users continues to grow monthly. The report provided demographics of Facebook users in the country, revealing an equal distribution of male and female, the majority of them (48.3%) being young people between the ages 18 and 35. However, the data provided by Facebrands may not be fully accurate (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1:

Evolution of number of Facebook users

Facebook offers many advantages for its users allowing them being in touch with old friends and/or establishing new ones (4). Four types of activities carried by Facebook users while being connected were described: electronic interactions with friends (such as posting, commenting, or replying to messages), voyeuristic actions (observing profile content than doing actual posting, sometimes referred to as “lurking” or “stalking”), self-presentation activities (revealing personal attitudes and interests as well as social connections through the information displayed on one’s Facebook page), and gaming - taking quizzes(5). In a study regarding university students, Facebook was used in order to find out what happens in university, to get access to shared resources, and to participate in group discussions (6). The time spent daily in the network was between 30 min and 3 h for each student, whereas females used the network longer compared to males.

Facebook use and depression

With the increased number of Facebook users, the problems associated with excessive use have become more and more frequent and caught researchers’ attention (7). However, studies concerning cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between Internet use and adolescent well-being have provided inconsistent results. The amount of time and intensity of the online world is thought to be a factor that may trigger depression for some adolescents (8). Over a period of 8 to 12 months, both loneliness and depression were increased with time spent online among adolescents’ internet users (9). Moreover, symptoms consistent with depression were found in status updates on Facebook, suggesting that depression stimulates users to speak out on Facebook, which may later lead to Facebook addiction (10). The number of hours students spend on Facebook was positively correlated with depression (11). Based on these previous findings we may conclude that depressive symptoms are more prevalent among excessive Facebook college students’ users (12, 13). Therefore, a new phenomenon called “Facebook depression” was proposed, defined as depression that develops when preteens and teens spend a great deal of time on social media sites, such as Facebook, and then begin to exhibit classic symptoms of depression (8).

However, other studies found there is no significant relation between Facebook use and depression. “Advising adolescent patients or parents on the risks of ‘Facebook depression’ may be premature” (14). Similarly, no direct association was found between Facebook use and depression, except for when envy is accounted for in the equation; then using Facebook for surveillance negatively predicts depression (15). There was no association between internet use and depression (16) and in a one-year follow-up study, the observed negative effects of Internet use had disappeared (17).

Facebook use and family satisfaction

The new Information Communication Technologies impacts multiple areas of family life (18). The nature of the human relations between the members (19), family cohesion, family functioning, family roles and boundaries are reconstructed in this technological environment supporting new interactions and relationship patterns among members. A correlation between problematic Internet use and family functioning has been previously demonstrated (20). Social networking sites as Facebook may lead to disagreements between members and lead to conflict in families (21). Besides, its indirect negative impact on family satisfaction was highlighted by decreasing the amount of time spent together (22). Alternatively, social networking sites may also provide new opportunities for family members to build enjoyable family relationships and support higher levels of family satisfaction. In this line of conceptualization, none of the family members they researched found social networking sites to be seriously detrimental to their lives or to their family satisfaction (23). However, “There is a tremendous need for studies that examine the effects of technologies on family functioning, processes, communication, roles and relationships” (24).

The main objective of this research was to examine the relationship between Facebook use, emotional state of depression, and family satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Based on previous results, we posed the following hypotheses:

H1. Depression is a positive contributor to Facebook engagement. Youth displaying higher depressive feelings use Facebook more intensively.

H2. Higher Facebook intensity is positively related to Facebook addiction.

H3. Facebook addiction is negatively related to family satisfaction.

Participants and procedure

The participants were 708 Facebook young users aged 13–35 (36% were females). The majority (70.3%) was residing in urban areas and 60.2% was enrolled in either high school or university. They were recruited through posting a link to the online survey created in Google Docs on the Facebook ‘wall’. The survey was available during Jun–Jul 2015 in Romania. The only condition one had to meet to take part in the study was having a Facebook account or at least a functional e-mail address. Data were firstly collected and imported into an Excel spreadsheet and verified, and then imported into an SPSS file and used in analysis. The participants received no remuneration. In the instruction, they were informed that the study concerned Facebook activity and that their contributions were anonymous. We used Romanian translated versions of all the instruments employed.

Instruments

The survey comprised a series of basic demographic questions (e.g., age, gender, education, occupation, location) as well as some measures of Facebook addiction, depression, and family satisfaction. We used two methods connected with extensive Facebook usage, the first one measuring only the intensity of use, and the second one measuring not only the intensity but also the consequences of this use. The methods used in the study have been widely applied in the subject literature, have good theoretical background, and showed good reliability in previous studies.

For measuring the intensity and frequency of Facebook usage, we used two items regarding the active engagement on Facebook page (How often do you post, text, like or share on Facebook?) and the time spent on the account (How many hours/day do you spend being online on Facebook?).

For measuring Facebook addiction, we used the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS) (25). The scale has been used for different European populations: Portuguese (26), Polish (7), and Turkish (27), proving good reliability. Initially containing 18 items, three reflecting each of the six core elements of addiction (salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse), the item with the highest corrected item-total correlation from within each of the six addiction components was retained in the final six-item scale. The Cronbach’s α reliability of the Romanian version was 0.78. The range of the Facebook Addiction Scale was from 1 to 5, a higher score indicating a more severe level of Facebook addiction.

To measure depressive state, we used Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI) – short version adapted into Romanian by AUTHOR (2010) (28). Beck’s Depression Inventory contains 14 items each answer being scored on a scale value of 0 to 3 and quantifying different levels of a person’s depression. The reliability of the scale Cronbach’s α) was 0.86.

Family satisfaction was measured with the Family Satisfaction by Adjectives Scale (FSAS) (29), consisting of 27 items designed to measure family satisfaction, mainly related to the affective connotation derived from family interaction. The scale was preceded by the sentence “When I am at home, with my family, I mostly feel ...,” the items being represented by a variety of adjectives that may reflect the different emotions evoked by the family. Subjects were able to choose between six alternative responses for each pair of adjectives, defined by the headings “Totally”, “Quite” and “To some extent”, to make it easier for them to choose the right degrees. By adding the responses, a composite score ranging from 27 to 162 was generated, with higher scores indicating higher satisfaction with family life. The reliability of the scale for our sample (Cronbach’s α) was 0.93. This scale has already been adapted and administered in a Portuguese population of families with children in the fourth grade (30), a Mexican population of children and adolescents (31), and a Turkish sample of youth and adults (32) proving strong validity and reliability.

Analyses

SPSS ver. 18.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows software was used to perform the statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were computed for the demographic characteristics. Internal consistency was measured using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient to assess the extent to which the BFAS, BDI and FSAS items were interrelated. In addition, correlation and ANOVA tests were used to test the association between the variables of interest. Results are displayed in tabular and graphic formats.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and correlations between variables: Facebook intensity, Facebook addiction, depression, and family satisfaction.

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics for Facebook intensity, Facebook addiction, depression and family satisfaction

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Facebook intensity | 2.90 | 1.04 | |||

| 2. | Facebook addiction | 1.81 | 0.75 | .537 *** | ||

| 3. | Depression | 0.29 | 0.37 | .225 *** | .304 *** | |

| 4. | Family satisfaction | 4.71 | 0.79 | −.124 *** | −.169 *** | −.453 *** |

P <0.001.

No significant differences were recorded for gender, except for Facebook addiction (t(529.49)= −2.21, P<0.05), girls (M=11.20) being more addicted than boys (M=10.41). The only significant difference for residency was recorded for family satisfaction (t(629)=2.16, P<0.05), respondents from urban areas (M=4.75) being more satisfied compared to their rural counterparts (M=4.60).

To examine Facebook addiction, a series of k-means cluster analyses were performed, resulting in subjects being assigned to three groups (ordinary, problematic, and addicted), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2:

Means and Standard Deviations for the three clusters

| Variable | Clusters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Facebook users (N = 415) | Problematic Facebook users (N = 193) | Addicted Facebook users (N = 43) | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Facebook addiction | 1.35 | 0.28 | 2.39 | 0.32 | 3.68 | 0.45 |

| Facebook intensity | 2.56 | 0.94 | 3.33 | 0.91 | 4.29 | 0.78 |

Cluster 1 comprised 415 participants with a low level of Facebook addiction (M=1.35, SD=0.28) and a low level of Facebook intensity (M=2.56, SD=0.94). This group was labeled “ordinary Facebook users”. Cluster 2 labeled “problematic Facebook users” comprised 193 participants with a medium level of Facebook addiction (M=2.39, SD=0.32) and a high level of Facebook intensity (M=3.33, SD=0.91). Cluster 3 comprised 43 participants characterized by a high level of Facebook addiction (M = 3.68, SD = 0.45) and a very high level of Facebook intensity (M=4.29, SD=0.78). This group was labeled “addicted Facebook users”.

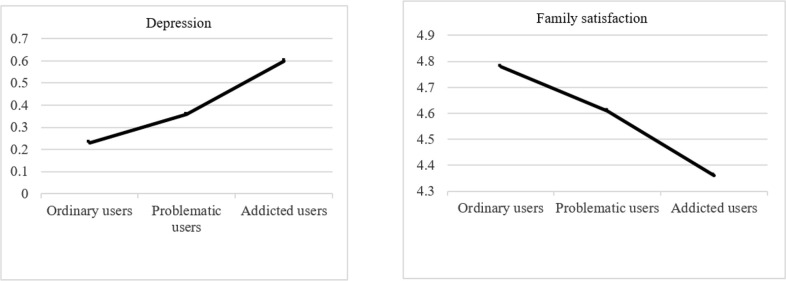

One-way ANOVA checking the differences between three groups was conducted (Table 3 and Fig. 2).

Table 3:

Means, Standard Deviations, and significant differences on depression and family satisfaction among the three groups

| Variable | Groups | F | Significance of difference between groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Facebook users | Problematic Facebook users | Addicted Facebook users | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Depression | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 25.73 *** | 1–2;3, 2–3 |

| Family satisfaction | 4.78 | 0.78 | 4.61 | 0.80 | 4.36 | 0.82 | 6.83 *** | 1–3 |

P < .05.

P < .01.

P < .001.

Fig. 2:

Differences between three groups of Facebook users in depression and life satisfaction

We concluded that ordinary Facebook users differed statistically from both addicted and problematic Facebook users in terms of depressive symptoms (F(2, 648)=25.73, P<.001) and addicted users differed from ordinary users for family satisfaction (F(2, 618)=6.83, P<.001). Ordinary Facebook users were characterized by lower levels of depression (M=0.23) and higher family satisfaction (M=4.78) than problematic and addicted users. Addicted Facebook users scored higher on depression (M=0.60) than ordinary and problematic users. Addicted Facebook users reported significantly lower family satisfaction (M=4.36) compared to ordinary users (M=4.78). These results shows that addicted Facebook users report more depressive symptoms and tend to have lower family satisfaction.

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to examine the relationship between Facebook use, depression, and life satisfaction. Moreover, one of the goals of this research was to investigate whether people with different levels of Facebook intensity and Facebook addiction differ in levels of reported depression and life satisfaction.

Because of the study, our hypotheses were supported. Facebook engagement is negatively related to family satisfaction. The level of family satisfaction was the lowest among addicted Facebook users when we compared these three groups. This contradicts study (23) concluded that social networking sites increased family satisfaction by allowing participants to stay in touch with extended family members and friends, and developing a sense of community. Our results support the statement that technology is mainly a negative factor in family life (34,35), relating excessive internet use in youth with the level of closeness in family relationships and communication (36–38).

Besides, Facebook engagement is positively related to depression symptoms. Subjects who scored higher on the addiction scale also have higher scores on the depression, thus we concluded that depression is an important factor of staying online for longer periods. Similarly to Moreau et al. (36), the score for depressive symptoms was higher for excessive users.

The Pearson correlations showed that higher Facebook intensity is positively associated to Facebook addiction. Therefore, the more time one invests in using Facebook the more likely one is to develop the addiction. This could be explained by the process of habituation that characterizes the process of developing an addiction. From this perspective, the division into three clusters may reflect the division of Facebook addiction into stages, from normal to excessive use. Ordinary Facebook users tend using Facebook more healthily (as a tool in meeting their goals and not as a goal in itself), they do not report having serious problems when need to quit Facebook platform. Therefore, they are not too much involved in it. They also record low levels of depression and high family satisfaction, which both may serve as a protective factor against developing a potential addictive behavior. Problematic Facebook users are the people who use Facebook intensively, but they are not yet recorded for having any serious problems (although the depression level is significantly higher than of ordinary users). This group is more vulnerable as some people may develop in future an addictive behavior once the level of family satisfaction lowers. Addicted Facebook users are persons who have problems because of Facebook. Their behavior may be to try limiting or quitting Facebook as they become aware of their problems (or others have made them aware), but it is beyond their control and these attempts generally result in failures. This may also explain our result of higher family dissatisfaction. As their level of depression is also higher, they do not derive satisfaction from Facebook usage and, therefore, it lowers their general satisfaction. Similarly, Facebook use predicts declines in the two components of subjective well-being: how people feel moment to moment and how satisfied they are with their lives (39).

This study has several limitations considered. One of its main limitations concerns the sampling procedure. Although the sample size (708 young users) can be considered satisfactory, it cannot represent the whole population of Romanian Facebook users as the study employed online survey which inadvertently excludes those with no or limited Internet access. Thus, the findings cannot be generalized to the Romanian youth population. However, the study provides useful insights about the Facebook use and potential mental health consequences of excessive usage by the youth. We consider that an important finding that emerges from this study is the presentation of the three phases of developing a Facebook addiction. This can be useful in both prevention and counselling practices. Future studies should extend the sample size and representativeness by following approaches that are more systematic to be able to generalize the results.

Another limitation is related to the research design. The results are based on a cross-sectional study. Many literature studies are cross-sectional, and longitudinal studies were carried out for short periods (33). More insight should be obtained from longitudinal approaches to describe more precisely the development of the phases of addiction and the causal effect of selected explanatory variables.

Conclusion

Youth who use Facebook more and more can be exposed to problems connected with Facebook. Results show that our hypotheses are supported. Nevertheless, this study contributes to the existing literature not only by examining the relationship between depression, family satisfaction, and Facebook use, but also by presenting the relationships between these variables in three groups of users in different phases of engagement.

This research contributes to literature in the field because it points out possible research directions, on the one hand, and because a cross-sectional study on Facebook use, depression, and family satisfaction is a first time for Romania, on the other hand. No doubt, better understanding the phenomenon needs more studies. In future, research needs to identify other predictors of this phenomenon.

Acknowledgements

Publishing current paper was financed through Entrepreneurial Education and Professional Counseling for Social and Human Sciences PhD and Postdoctoral Researchers to ensure knowledge transfer Project, financed through Human Capital Programme (ATRiUM, POCU380/6/13/123343).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

References

- 1.Enberg J. (2016). Global Social Platforms 2016: A Country-by-Country Review of Social Network Usage. E-Marketer. Available from: https://www.emarketer.com/Report/Global-Social-Platforms-2016-Country-by-Country-Review-of-Social-Network-Usage/2001740

- 2.Facebook (2017). Key facts. Available from: https://newsroom.fb.com/company-info/

- 3.Facebrands (2017). Demographic data Facebook users Romania. Available from: http://www.facebrands.ro/demografice.html

- 4.Ellison N, Steinfield C, Lampe C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends”: social capital and college students’ use of online social networking sites. J Comput Mediat Commun, 12(4): 1143–1168. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang CC, Brown BB. (2013). Motives for Using Facebook, Patterns of Facebook Activities, and Late Adolescents’ Social Adjustment to College. J Youth Adolesc, 42 (3): 403–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iordache DD, Pribeanu C, Lamanauskas V, Raguliene L. (2015). Usage of Facebook by University Students in Romania and Lithuania: A Comparative Study. Informatica Economica, 19 (1): 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Błachnio A, Przepiorka A, Pantic L. (2016). Association between Facebook Addiction, Self-esteem and Life Satisfaction: A Cross-sectional Study. Comput Human Behav, 55: 701–705. [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Keeffe GS, Clarke-Pearson K. (2011). The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics, 127 (4): 800–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraut R, Patterson M, Lundmark V, et al. (1998). Internet paradox: a social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am Psychol, 53 (9): 1017–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreno MA, Jelenchick LA, Egan KG, et al. (2011). Feeling Bad on Facebook: Depression Disclosures by College Students on A Social Networking Site. Depress Anxiety, 28 (6): 447–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright KB, Rosenberg J, Egbert N, et al. (2013). Communication competence, social support, and depression among college students: A model of Facebook and face-to-face support network influence. J Health Commun, 18(1): 41–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong FY, Huang DH, Lin HY, Chiu SL. (2014). Analysis of the psychological traits, Facebook usage, and Facebook addiction model of Taiwanese university students. Telematics and Informatics, 31: 597–606. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koc M, Gulyagci S. (2013). Facebook addiction among Turkish college students: The role of psychological health, demographic, and usage characteristics. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw, 16(4): 279–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jelenchick LA, Eickhoff JC, Moreno MA. (2013). “Facebook Depression?” Social Networking Site Use and Depression in Older Adolescents. J Adolesc Health, 52 (1): 128–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tandoc EC, Ferruci P, Duffy M. (2015). Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: is facebooking depressing? Comput Human Behav, 43: 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selfhout MHW, Branje SJT, Delsing M, et al. (2009). Different types of Internet use, depression, and social anxiety: the role of perceived friendship quality. J Adolesc, 32(4): 819–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kraut R, Kiesler S, Boneva B, et al. (2002). Internet paradox revisited. Journal of Social Issues, 58: 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carvalho J, Francisco R, Relvas AP. (2015). Family functioning and information and communication technologies: How do they relate? A literature review. Comput Human Behav, 45: 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrioni F. (2011). The socio-economic effects of Romanian parents’ emigration on their children’s destiny. Annals of the University of Petroşani, Economics, 11(4): 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yen JY, Yen CF, Chen CC, et al. (2007). Family factors of internet addiction and substance use experience in Taiwanese adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav, 10(3): 323–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huisman S, Edwards A, Catapano S. (2012). The impact of technology on families. International Journal of Education and Psychology in the Community IJEPC, 2(1): 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mesch GS. (2006). Family relations and the internet: Exploring a family boundaries approach. J Fam Commun, 6(2): 119–138. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharaievska I, Stodolska M. (2017). Family satisfaction and social networking leisure. Journal Leisure Studies, 36 (2): 231–243. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanigan JD. (2009). A Sociotechnological model for family research and intervention: How information and communication technologies affect family life. Marriage & Family Review, 45(6–8):587–609. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, Pallesen S. (2012). Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychol Rep, 110(2): 501–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pontes HM, Andreassen CS, Griffiths MD. (2016). Portuguese Validation of the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale: an Empirical Study. Int J Ment Health Addict, 14 (6): 1062–1073. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uysal R, Satici SA, Akin A. (2013). Mediating Effect of Facebook Addiction on the Relationship between Subjective Vitality and Subjective Happiness. Psychol Rep, 113 (3): 948–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.AUTHOR (2010). Depresia la persoanele vârstnice. Editura Excelsior Art, Timişoara. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barraca J, López-Yarto L, Olea L. (2000). Psychometric Properties of a New Family Life Satisfaction Scale. Eur J Psychol Ass, 16 (2): 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nave F, de Jesús SN, Mairal JB, Parreira P. (2007). Adaptación de la Escala de Satisfacción Familiar por Adjetivos (ESFA) a la población portuguesa. (Adaptation of the Family Satisfaction by Adjectives Scale (FSAS) to the Portuguese population). Ansiedad y Estrés, 13: 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quintanilla GT, Sotomayor MDDL, Hernández OM, et al. (2013). Family Satisfaction by Adjectives Scale (FSAS) in Mexican Children and Adolescents: Normative data. Salud Mental, 36(5):381–386. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tasdelen-Karçkay A. (2016). Family Life Satisfaction Scale-Turkish Version: Psychometric Evaluation. Social Behavior and Personality An International Journal, 44 (4): 631–640. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCrae N, Gettings S, Purssell E. (2017). Social Media and Depressive Symptoms in Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Adolesc Res Rev, 315–330. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chelsey N. (2005). Blurring boundaries? Linking technology use, spillover, individual distress, and family satisfaction. J Marriage Fam, 67(5): 1237–1248. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watkins SC. (2009). The young and the digital: What the migration to social-network sites, games, and anytime, anywhere media means for our future. ed. MA: Beacon Press, Boston. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabasakal Z. (2015). Life satisfaction and family functions as-predictors of problematic Internet use in university students. Comput Human Behav, 53: 294–304. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreau A, Laconi S, Delfour M, Chabrol H. (2015). Psychopathological profiles of adolescent and young adult problematic Facebook users. Comput Human Behav, 44: 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turow J. (2001). Family boundaries, commercialism, and the Internet: A framework for research. J Appl Develop Psychol, 22(1):73–86. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kross E, Verduyn P, Demiralp E, et al. (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS One, 8(8):e69841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]