Abstract

Dementia is a widely recognized public health priority due to the increasing number of people living with the condition and its attendant health, social, and economic costs. Delivering appropriate care is a challenge in many countries in Europe contributing to unmet needs of people living with dementia. Acute hospital settings are often the default route in pursuit for dementia care due to the lack of or limited knowledge of local service provisions. The care environment and the skillsets in acute hospitals do not fully embrace the personhood necessary in dementia care. Predictions of an exponential increase in people living with dementia in the coming 30 years require evidence-based strategies for advancing dementia care and maximizing independent living. However, the evidence required to inform priorities for enabling improvements in dementia care is rarely presented in a way that stimulates and sustains political interests. This scoping review of the literature drew on principles of meta-ethnography to clarify the gaps and priorities in dementia care in Europe. The review constituted eight papers (n = 8) and a stakeholder consultation involving three organizations implementing dementia care programs in Europe comprising Emmaus Elderly Care in Belgium, Residential Care Holy Heart in Belgium, and ZorgSaam in the Netherlands. Overarching concepts of gaps identified include fragmented non-person-centered care pathways, the culture of dementia care, limited knowledge and skills, poor communication and information sharing, and ineffective healthcare policies. Key areas distinguished from the literature for narrowing the gaps to improve care experiences and the support for people living with dementia care encompass person-centered care, integrated care pathways, and healthcare workforce development. Action for advancing care and maximizing independent living needs to go beyond mere inclusions on political agendas to incorporate a shift in health and social care policies to address the needs of people living with dementia.

Keywords: dementia care, care priorities, gaps in care

Introduction

Dementia is a widely recognized public health priority due to the increasing number of people living with the condition and its attendant health, social, and economic costs. In the United Kingdom (UK), for example, the number of people with dementia is expected to rise to over 2 million in the next 30 years, with an overall economic impact cost of about £26 billion (US$35 billion) per annum (Prince et al., 2014). In 2010, high-income countries accounted for 46% of the global prevalence of dementia and 89% of the total global dementia costs estimated at US$604 billion, 70% of which was incurred through healthcare (Prince, Guerchet, & Prina, 2015). The term dementia describes an array of varying symptoms emanating from disorders that impair the human brain, most commonly, but not uniquely, in older people (Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCP), 2017). Delivering appropriate dementia care is a challenge in many countries in Europe contributing to unmet needs of people living with dementia (Van de Voorde et al., 2017). We use the term people living with dementia to represent not only the person diagnosed with the condition but also the constellation of people immediately affected by the diagnosis. Acute care settings are often the default route in pursuit for dementia care due to the lack of or limited knowledge of community service provisions (Lathren, Sloane, Hoyle, Zimmerman, & Kaufer, 2013). The focus in acute hospitals is on the primary issue leading to admission, which is often non-definitive and the challenges of accessing specialized care become overwhelming (Houghton, Murphy, Brooker, & Casey, 2016). While the apparent cost of dementia care is rising apace, there also seems to be increasing demand for specialized care of up to 40% where this already exists (Van de Voorde et al., 2017).

The majority of countries in Europe are cognizant of the rising prevalence of dementia and thus have dementia care strategies in place but with varying priorities and emphases (Nakanishi et al., 2015). The World Dementia Council (WDC; 2017) global care statement calls for evidence-based improvements in the quality of dementia care, with emphasis on care planning for better health outcomes, improved comfort, and reduced anxiety for people with dementia. Unfortunately, the growing body of research evidence on dementia is seldom presented in a form that stimulates policy action to enable required improvements to happen (Quaglio, Brand, & Dario, 2016). Our scoping review of the literature aimed to map gaps and priorities in dementia care in Europe to inform innovations for improved models of dementia care and support. The review focuses on gaps relating to delivery of care for the condition of dementia instead of inequalities in healthcare delivery that may be due to demographic factors.

Methods

Design

We used Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) scoping review framework to map key concepts across different studies and to generate a summary of broad areas for gaps and priorities in dementia care. We drew on principles of meta-ethnography (Noblit & Hare, 1988) to transcend the conventional aggregation of results and to enable the interpretation of findings from different studies in a more practical and illuminating way. Meta-ethnography is a structured way of analyzing and interpreting data cross published results of qualitative studies (Erwin, Brotherson, & Summers, 2011). Meta-ethnography complemented the scoping review approach, specifically in focusing the scale for gap analyses and overcoming the generalization of different aspects of the wide spectrum of research on dementia. We used systems theory (Von Bertalanffy, 1977) to support the interdisciplinary conceptualization of interdependent parts that create gaps in care and those required to work in tandem to improve the quality of dementia care.

The review aimed to answer the question, “what are the gaps and priorities for dementia care in Europe?” The research question called for studies that employed a gap analysis approach to simplify the process of distinguishing strategies for holistic resolution of issues that would otherwise be traced through consulting various sources of information. A gap analysis in healthcare is a data-driven method that helps to identify the priority care needs amidst competing possibilities (Golden, Hager, Gould, Mathioudakis, & Pronovost, 2017).

Identifying relevant studies

We identified papers relevant to the study through an electronic search of four databases, including EMBASE, CINHAL, Medline, and PsycINFO. We used the SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) framework (Cook, Smith, & Booth, 2012) to facilitate the rigor in defining important aspects of the research question and logic combination of search terms. We focused the search on the literature published in English from January 2007 to May 2017 to identify the evidence taking into account recent policy developments in dementia care. A search for evidence published outside the conventional peer review routes supplemented the search in electronic databases. Table 1 shows the search terms identified with the help of the SPIDER framework.

Table 1.

Search terms.

| Sample | Phenomena of interest | Design | Evaluation | Research type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| People living with dementia | Dementia care | Gap analysis | Gaps in dementia carePriorities identified to narrow gaps | Qualitative |

| [Dementia] OR [Alzheimer*] OR [Neurodegenerat* disease*] | [Care] | [Evaluat* ] OR [Analys*] OR [Review*] OR | [Gaps] OR [Inequ*] AND [Priorit*] | [Qualitative] |

Selecting relevant studies

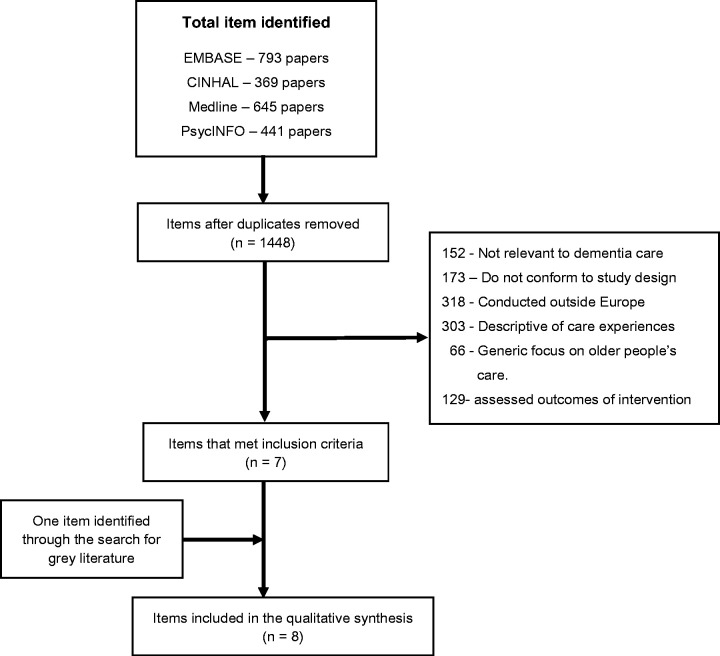

Studies qualified for inclusion in the scoping review if they analyzed the performance of dementia care and also highlighted the best practice or strategies for attaining desired performance. Figure 1 illustrates the process of screening for relevant items.

Figure 1.

Process of screening citations returned to identify the relevant items.

We excluded items if they:

were primary studies conducted outside of Europe;

were descriptive, editorials, or commentaries;

had a generic focus on older people’s care; and/or

assessed pre-determined outcomes of an intervention.

Studies employing quantitative methods were excluded because they do not conform to principles underpinning meta-ethnography. Meta-ethnography involves reinterpretation of interpretations of published qualitative research (Pilkington, 2018). We also omitted the search of bibliographies of included reviews of the literature on the basis that authors’ syntheses of gaps and priorities in dementia care were adequately grounded in the results of primary studies.

Quality appraisal of studies

For many qualitative reviews, researchers feel the need to succumb unnecessarily to the pressure of appraising papers for inclusion to avoid the health community stigma related to gold standard methods (Toye et al., 2014). We made a cautious decision to prioritize the relevance of papers over quality determined by methodological rigor to maximize the contribution of conceptual and methodological heterogeneity for formulating overarching concepts (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006).

Charting the data

Two reviewers independently read papers included in the review and used a predetermined online template (google forms) to record characteristics of studies (Table 2) plus gaps and priorities in dementia care distinguished in each of the studies. This was in the form of short sentences of key concepts that most suitably summarized identified gaps and care priorities while maintaining consistency with the original wording of the papers. The online template programmed data charted into coherent categories. The number of papers included in the review (n = 8) provided sufficient data for mapping key concepts of gaps and priorities in dementia care. A third reviewer examined completed data charts for consistency to enhance the credence of the synthesis. We resolved variations by revisiting and discussing original items to achieve consensus. The reconciled data chart provided a summary of concepts derived from studies constituting the scoping review.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included in the scoping review.

| Study | Design | Conceptual perspective | Sample | Country | Focus | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buswell et al. (2014) | Integrative review | None mentioned | 17 Sources included | UK (n = 11)US (n = 4) Australia (n = 1) Review (n = 1) | Examining the role of emergency services unplanned, urgent, and emergency care for older people with dementia | Synthesis of selected papers |

| Dening et al. (2012) | Qualitative study | Whole system | Health and social care staff (n = 50) | England | Identifying perceived and real barriers that prevent people with dementia and their carers receiving end-of-life care of acceptable quality | Focus groups semi-structured interviews |

| Gotts et al. (2016) | Mixed methods—narrative review and survey | None mentioned | 42 sources included in reviewCommissioners (n = 20) | England | Investigating the commissioning of end-of-life dementia care | Literature reviewSemi-structured interviews |

| Houghton et al. (2016) | Qualitative evidence synthesis | Values, Individualized, Perspective & Social and psychological framework synthesis | 9 Sources included | Canada (n = 1) England (n = 1) Australia (n = 4) Ireland (n = 1) Scotland (n = 1) Sweden (n = 1) | Exploring healthcare staffs’ experiences and perceptions of caring for people with dementia in the acute setting to inform policy development | Synthesis of selected papers |

| Melin Emilsson (2009) | A comparative qualitative study | Relation and intercultural orientation | 98 Participants in 22 care settings | FrancePortugalSweden | Describing, analyzing and comparing different focuses on care of older people with dementia | Semi-structured interviewsFocus groups informal interviewsObservations |

| Risco et al. (2016) | Qualitative study | None mentioned | Healthcare staff (n = 25) Informal carers (n = 20) People with early dementia (n = 15) | Spain | Identifying barriers and facilitators in dementia care relating to proving information, communication, and working collaboratively | Focus groups |

| RCP (2017) | National audit | National and professional guidance | Hospitals (n = 199) Casenotes (n = 10,047) Staff (n = 14,416) Carer (n = 4664) | UK | An audit of dementia care measuring the performance of general hospitals | SurveysCase note auditOrganizational checklist |

| Turner, Eccles, Elvish, Simpson, and Keady (2017) | Meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence | Critical realist/objective idealism | 14 Sources included | Australia (n = 2) Ireland (n = 2) Sweden (n = 2) UK (n = 8) | Examining healthcare staffs’ experiences and perceptions of caring for people with dementia in the acute settings to inform future training needs | Meta-ethnography |

Collating and summarizing results

Using principles of meta-ethnography (Noblit & Hare, 1988), the first step involved comparing charted concepts to identify the key constructs that described a range of other concepts to represent the next level in the synthesis grid. Meta-ethnography draws on a cumulative build of concepts resulting from information extracted from individual studies published about a credibly related topic (Pilkington, 2018). The process entails systematic meld of relevant information extracted from published results of individual studies through interpretation to generate all-encompassing concepts that would not ideally describe findings of an individual study (Pilkington, 2018). We used synthesis argument (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006) to incorporate evidence across studies into a grid of concepts based on the original studies included in the review. Whereas line augment requires ordered interpretations, synthesis argument supports the fluid use of concepts to enable links between conceptual developments of primary studies and synthetic concepts (concepts derived by authors) (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006).

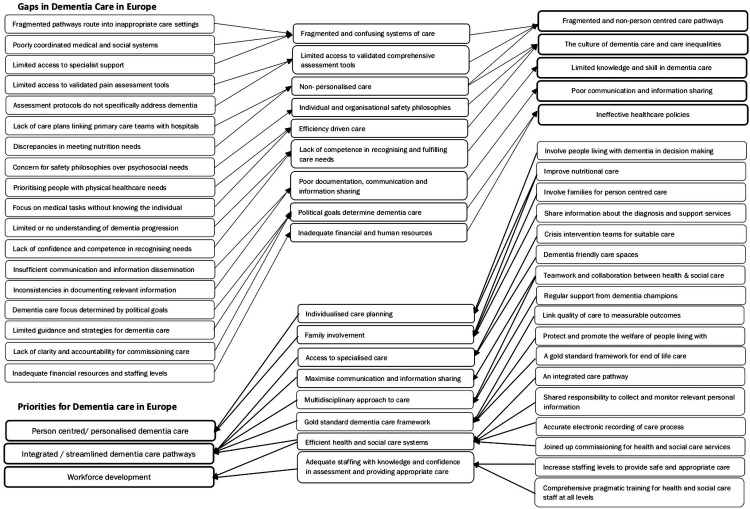

Our synthesis argument questioned included studies for elements of personhood and holistic care to form unified explanations for different aspects of the gaps and priorities identified in dementia care. Personhood in dementia care is a value that enables practitioners to look beyond the condition and develop understanding of the person with dementia, including but not limited to their emotions, preferences, and family history (Kontos, Mitchell, Mistry, & Ballon, 2010). Systems theory (Von Bertalanffy, 1977) facilitated the organization of concepts in an interdisciplinary manner to form a purposeful whole. Von Bertalanffy postulates that systems are open to interactions with and within their environment, through which they develop new relations. This analogy supported our conceptualization of prerequisites, processes, and outputs through collating and interpreting relationships and interaction of elements required for sustainable person-centered outcomes. On the basis that systems constitute subsystems with permeable boundaries (Von Bertalanffy, 1977), we derived synthetic concepts through continuous comparison of concepts and questioning of purposeful activity in relation to holistic dementia care. Figure 2 illustrates how we assimilated evidence across various studies included in the review into a grid of constructs.

Figure 2.

Grid of analytical concepts and their interaction and the relationships between them.

Consultation

Arksey and O’Malley (2005) recommend consulting with stakeholders to make results of a scoping study more useful and practical. We asked three organizations involved in providing direct care and support for people living with dementia to comment on how representative the results were of the situation in Europe and to identify further references. Organizations included Emmaus Elderly Care and Residential Care Holy Heart in Belgium and ZorgSaam in the Netherlands. The feedback endorsed the consistency of results with the current situation of dementia care in Europe and pointed to existence of more evidence published in other languages other than English. There was a general concern about the omission of studies employing quantitative designs, which did not match the qualitative design of the review. The consultation feedback, however, endorsed the value of the results for innovations relating to person-centered dementia care practices. Below are some of statements that endorsed the findings from the scoping review:

Clearly highlights the issues surrounding the person living with dementia and their family. We need to learn from each other and develop an integrated model which embraces health and social care. Community links are vital and we need to maximise those. (Stakeholder representative 1)

The outcomes are not surprising and are already mentioned in CASCADE (Community Areas of Sustainable Care And Dementia Excellence in Europe). One aspect that is very crucial for development is the different financial systems and how much budget is available. The last aspect has to be mentioned and can limit development but can also stimulate innovations. (Stakeholder representative 2)

Results

Characteristics of items selected for synthesis

The electronic search returned 2248 citations that totaled to 1448 after removing duplicates. An additional 1264 irrelevant citations were excluded on screening title and abstracts. Full texts for 184 items were assessed for eligibility for inclusion in the review. A total of 177 more citations were excluded: 7 were not relevant to dementia care, 43 did not match the qualitative design of the review, 36 were conducted outside of Europe, 67 described dementia care experiences, 14 had a generic focus on older people’s care, and 10 assessed outcomes of interventions for dementia care. The search for gray literature yielded one report relevant to the objectives of the scoping review. Table 2 shows some of the features of studies included in the synthesis.

We extracted data from seven articles and one audit report. The articles comprised three reviews of dementia care and four primary studies. Two of the primary studies explored views of people living with dementia and health and social care staff in the UK (Dening, Greenish, Jones, Mandal, & Sampson, 2012) and in Spain (Risco et al., 2016). Melin Emilsson (2009) employed a comparative approach to investigating views of health and social care staff in long-term care facilities in France, Portugal, and Sweden, while Gotts et al. (2016) conducted a survey of commissioners of end-of-life care in the UK. The evaluation report assessed dementia care in general hospitals in the UK (RCP, 2017). Selected reviews investigated urgent and emergency care for older people with dementia (Buswell et al., 2014) and staff experiences of dementia care in acute settings (Houghton et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2017).

Gaps in dementia care

Gaps in dementia care highlight characteristics and performance of dementia care in countries across Europe including France, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the UK. The gaps identified refer to factors embedded within systems of care for dementia in different settings as opposed to care inequalities that may result from demographic aspects such as gender, age, race, or economic characteristics.

Fragmented non-person-centered care pathways

The literature identifies more problems than solutions to the ineffective structure of dementia care pathways. People living with dementia find social and healthcare systems fragmented, confusing, and difficult to navigate (Buswell et al., 2014). Ineffective care pathways trigger transfers of people with dementia to inappropriate care settings, which leads to unnecessary medical interventions, extended lengths of stay in acute care settings, and poor experiences of care (Houghton et al., 2016). People living with dementia frequently use emergency care services such as ambulances and emergency departments to overcome difficulties encountered in navigating care pathways, including end-of-life care (Buswell et al., 2014). However, emergency care services lack the expertise and validated tools to undertake robust assessments of dementia care needs (Buswell et al., 2014).

The care required to meet complex medical and social needs at different stages of dementia is often poorly coordinated with limited access to specialist care and support from relevant services, especially at the end of life (Dening et al., 2012; Houghton et al., 2016). The focalized approach on the role of doctors and nurses in acute care settings categorically confines the care that people living with dementia receive to the biomedical domain without due consideration of their psychosocial and indeed other care needs (Melin Emilsson, 2009). Health and social care providers in the community have limited understanding of the importance of anticipatory care planning, which contributes to makeshift visits to unsuitable care settings in pursuit for urgent care (Dening et al., 2012). The lack of emphasis on care planning frequently means that it is up to emergency responders or family caregivers to make complex decisions about appropriate care with insufficient information and support including decisions affecting the person’s end-of-life care (Dening et al., 2012).

The culture of dementia care

Healthcare practitioners in primary care contexts are seldom willing to discuss a possible dementia diagnosis due to the lack of confidence and the perception that the person will die with, if not of their dementia (Dening et al., 2012). While a diagnosis does not spell immediate loss of capacity, the literature identifies a common disregard of the preferences, values, and needs of people living with dementia, which differentiates dementia care from the care for other debilitating conditions (Houghton et al., 2016). This is particularly common when choosing a care setting in which the person with dementia may spend the last days of life (RCP, 2017).

Evidence in the literature also highlights that healthcare practitioners mostly in acute care settings have varying attitudes towards providing care for people with dementia, in many cases associated with avoidance (Turner et al., 2017). Organizations driven by considerations of cost-efficiency mostly provide the care for people with dementia within contexts marked by limited resources (Houghton et al., 2016). Emphasis in these contexts is usually on completing physical care tasks without allocating adequate time to get to know the person with dementia. The focus is also on individual and organizational philosophies of safety, deprioritizing equity, dignity, and respect (Houghton et al., 2016). This is evident in the labels used in frontline healthcare practice for people with dementia such as “difficult patient” (Turner et al., 2017) and the methods used to deescalate challenging behaviors (Houghton et al., 2016). The care culture in acute hospital settings prioritizes people with less complex healthcare needs and practitioners tend to spend less time on the care for people with dementia (Turner et al., 2017). This creates a cavernous divide between care experiences of people living with dementia and other healthcare service users.

Limited knowledge and skill in dementia care

Most of the inequities that people with dementia encounter in all healthcare settings correlate with staff’s lack of knowledge, skills, and the confidence to meet the needs of people living with dementia (Buswell et al., 2014; Houghton et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2017). The literature identifies a shared lack of understanding and proper management of the different stages of dementia progression among healthcare practitioners. This contributes to indecision about care options and a lack of continuity, particularly in the presence of a sudden change in the condition of the person with dementia (Dening et al., 2012).

Poor communication and information sharing

Most care contexts collect relevant information about people with dementia to facilitate the personalized care, but what is collected, documented, and how it is documented are habitually inconsistent, posing safety risks to people with dementia (RCP, 2017). Initial assessments of confusion and emergency care delivered in people’s own homes are rarely recorded, resulting in missed opportunities to share information about possible indications to enable earlier intervention and personalized care (Buswell et al., 2014; RCP, 2017). Poor interagency communication and information sharing also limits collaborative working and heightens risks of medical harm (Risco et al., 2016). Some of the staff involved in delivering care have sporadic access to information that could facilitate the optimal fulfilment of nutritional and communication needs of people with dementia (RCP, 2017).

People living with dementia generally receive limited information about the diagnosis and support services available until they need the information urgently (Risco et al., 2016). This is partly due to the length of appointments in primary care settings and outpatient departments that restricts the amount of information shared about the likely course of the condition. However, other evidence in the literature cites communicating with people living with dementia being a skill inherently lacking and an anxiety for many staff (Houghton et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2017). Healthcare staff lack the knowledge of means of establishing meaningful interaction and sharing relevant information with people living with dementia.

Ineffective healthcare policies

Political goals in different countries shape the focus of dementia care, including commissioning priorities (Gotts et al., 2016). Political interests determine whether dementia care has a medical, social care, or integrated health and social care focus (Melin Emilsson, 2009). The variations between national and local political goals are common, with little effort to establish a discernible benchmark to address challenges in dementia care. Some organizations have dementia care policies, which are rarely reflected in care experiences (RCP, 2017). Systems of medical and social aspects of care are mostly poorly coordinated, leading to inefficiencies and unmet care needs (Melin Emilsson, 2009). In England, for example, the confusing, non-standardized, and fragmented commissioning guidance places dementia care on the periphery of the healthcare commissioning framework (Gotts et al., 2016). Gotts et al. (2016) point to the lack of clarity and accountability for commissioning processes due to inconsistencies in the structure and governance of local clinical commissioning groups.

Dementia care priorities

In this section, we present areas recommended in the literature as key to dementia care improvements or identified as best practices for high-quality dementia care. These are distinguished as priorities to incorporate in broader public health strategies to address dementia care needs efficiently and sustainably.

Person-centered dementia care

It is essential that dementia care provided globally is person centered and conforms to the highest possible standards of quality, safety, and effectiveness (WDC, 2017). Person centeredness in dementia care aims to sustain the person’s identity that is vulnerable to progressive cognitive decline (Houghton et al., 2016). Person-centered dementia care distinguishes individualized care achieved through a care plan developed with the person with dementia and those closest to them (WDC, 2017). A dementia care plan focuses on meeting comprehensively assessed care needs, respects individual preferences, and enables flexible delivery of care and support services from the point of diagnosis to end of life (Dening et al., 2012; Houghton et al., 2016). Person-centered dementia care encompasses recognizing individuality of the person as a whole and getting to know them and their diagnosis. Health and social care professionals achieve this through building relationships, involving families and maximizing communication with people living with dementia to draw on their expertise, as well as provide relevant information about stages of the dementia trajectory and supportive services available (Houghton et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2017). Continued improvements in person-centered dementia care require open dialogue about care needs including changes in the person’s condition, discharge planning where relevant, and support services (RCP, 2017).

Integrated care pathways

The literature identifies an urgent need for functional dementia care pathways to enhance the access to specialized care and to minimize the disruptions to care plans (Houghton et al., 2016; Risco et al., 2016). There is an emphasis on integrated care systems guided by a standard framework for good practice in enabling evidence-based person-centered dementia care (Gotts et al., 2016; Melin Emilsson, 2009; RCP, 2017). An integrated dementia care pathway serves to protect and promote the welfare of people in a safe and independent environment, to support an active life, seamless care across professional boundaries, and dying well with dignity (Melin Emilsson, 2009). Seamless care also includes access to specialized dementia friendly spaces and well-coordinated personalized care across different health and social care settings (Risco et al., 2016). However, this requires concerted emphasis on care planning with joint commitment to collecting, sharing, and monitoring of relevant information for people living with dementia (RCP, 2017).

Effective integrated care systems enable rapid response to assessments and management of dementia care needs facilitated by partnerships and interdisciplinary teams (Houghton et al., 2016). Integrated care systems allow for alignment of dementia champions and palliative crisis intervention teams with other health and social care teams to provide support in different care contexts and reduce inappropriate hospital admissions, especially at the end of life (Dening et al., 2012; RCP, 2017). Joined up commissioning of health and social care services linked to measurable outcomes potentially generates more accurate evidence about the incidence of dementia, quality of care, and value on investment (Gotts et al., 2016).

Healthcare workforce development

Evidence in the literature identifies a critical need to address the capacity of the workforce involved in dementia care, to enhance the quality of care, and to retain the expertise within health and social care systems (Buswell et al., 2014; Dening et al., 2012; Houghton et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2017). This includes staffing levels in all care settings and careful assessment of learning and development needs to enable staff to gain the knowledge and skills in dementia care. Learning and development must be based on comprehensive and pragmatic frameworks to improve staff confidence in using care guidelines and evaluation tools for accurate assessments of cognitive impairment and mental capacity as well as managing care (RCP, 2017). Raising awareness about mental capacity empowers the workforce to support the people living with dementia with issues relating to consent, best interest decision-making, lasting power of attorney, and advance decision-making (RCP, 2017). The views of people living with dementia should inform learning and development frameworks for both senior and junior staff, including management teams to support continued improvements in care environments, staff confidence, and perceptions about dementia care (Turner et al., 2017).

Implications for policy, research, and practice

Dementia is one of the leading causes of disability in older people, and the condition is associated with social and economic complexities (United Nations, 2015). Globally, most countries have established dementia care strategies but with varying priorities ranging from emphasis on early diagnosis to high-quality end-of-life care (Nakanishi et al., 2015). This variation combined with a lack of political commitment to advancing dementia care present challenges to reliably good care and support for people with dementia (Quaglio et al., 2016). Our scoping review of the literature focused on analyses of gaps in dementia care and key means of closing or at least narrowing the chasm. Although emphasis was on Europe, reviews included in the synthesis examined evidence from a range of high-income countries worldwide, and the dementia care challenges identified were not variant.

The findings highlight that most healthcare systems in Europe are designed to tackle distinct illnesses without much scope for interaction between different parts of systems. Delayed diagnoses, care in inappropriate and distressing settings, and unnecessary early transfers to long-term care facilities embody dementia care provided within disjointed care systems (Houghton et al., 2016; Risco et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2017). Fragmentation is apparent not only in the system-based approaches to providing care but also in the hegemony of biomedical diagnoses, which focus on the condition and its management with little or no concern for social health of the person with dementia (de Vugt & Dröes, 2017). This dichotomy breeds experiences of poor quality service and futile efforts for improvement (Stange, 2009). Proponents of social health believe that impaired functioning does not immediately alter the quality of life. This is when people are supported to develop strategies for maintaining balance between opportunities and limitations to manage life with some independence to participate in social activities for individual growth (Brooker & Latham, 2015; Huber et al., 2011).

Integrated health and social care is at the forefront of best practice in delivering good quality dementia care (Melin Emilsson, 2009; WDC, 2017). For example, integrated communication and information storage systems across health and social care organizational boundaries maximize opportunities for sharing relevant information to enable personalized care, timely communication, collaborative working, and continuity of care across the dementia trajectory (Protti, 2009; Risco et al., 2016). However, the stigmatization of dementia as a condition without economic viability foils the commitment to policy transformation and the financial resources needed for improvements (Bond et al., 2005). While dementia is not unique to older people, the common use of disability adjusted life measures to determine healthcare budgets in countries worldwide (Lloyd-Sherlock et al., 2012) renders people with dementia vulnerable to healthcare inequities. Successful implementation of integrated health and social care requires a shift in policy championed by transformational leadership, committed partnerships, and adept interdisciplinary teams to effectively support the people living with dementia (Vedel, Trouvé, Jean, Ankri, & Somme, 2013).

Our findings cite a developed culture for dementia care that categorically pushes people living with dementia through the cracks in health and social care systems. Personalized dementia care often used interchangeably with person-centered care recognizes humanity irrespective of cognitive ability, individual uniqueness, empathy, and support for psychological needs (Brooker & Latham, 2015). A literature review of the state of care for older people with dementia in general hospitals (Dewing & Dijk, 2016) stimulates debate about the feasibility of person-centered care in acute care settings. On the other hand, healthcare systems are learning organizations (Khachaturian et al., 2017), and thus the focus should not be the “dementia” but advancing care and scientific knowledge to tackle a public health issue effectively.

Results of the review highlight a critical need to empower staff involved in dementia care with the skills required to improve their confidence in delivering care. The lack of competence in dementia care strongly associates with job strain and dehumanized delivery of care in frontline practice (Edvardsson Sandman, Nay, & Karlsson, 2009). The literature around training staff for improved practices in dementia care underscores the significance of at least foundation knowledge in principles of person-centered care, effective communication, and establishing meaningful interaction with people with dementia (Beer, 2017; Eggenberger, Heimerl, & Bennett, 2013; Robinson, Bamford, Briel, Spencer, & Whitty, 2010). Various programs have been developed in response to appeals for adequate staff training in dementia care, but their effectiveness is yet to be established (Whitlatch & Orsulic-Jeras, 2018). Evidence-based workforce development thus lurks, with greater need for programs incorporating both training and practice opportunities for enhanced confidence in dementia care (Banerjee et al., 2017).

One of the limitations of the findings of the review relates to the small number of studies included, indicative of the lack of gap analyses in this domain. Evidence existent in the literature describes dementia care experiences, barriers to effective care, and/or facilitators for improved care in isolation. The methodological emphasis on gap analyses may have restricted access to published literature that does not have use terms matching our broad search terms. Another limitation is the qualitative design of the review, which did not lend itself to the inclusion of studies with quantitative research designs. Further work incorporating quantitative studies on a wider scale is required to inform national strategies for improving dementia care in different healthcare systems and economies.

Conclusion

The mere inclusion of dementia care on political agendas is no longer sufficient to indicate a genuine concern for advancing care and maximizing independence. In the short term, linking healthcare and support services to promote care in suitable contexts and developing the workforce to enable improved care experiences are vital priority contributions to sustainable improvements in dementia care. Innovations for improvements need to build on what works to optimize efficiency in tackling yet another public health predicament.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the CASCADE Working Group for the feedback given during consultation: East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust, Emmaus Elderly Care, Flemish Expertise Centre on Dementia, HZ University of Applied Sciences, Medway Community Healthcare, Residential Care Holy Heart, The Health and Europe Centre, University of Lille 3, and ZorgSaam.

Biography

Anne Martin is a research fellow in the England Centre for Practice Development, Faculty of Health and Wellbeing at Canterbury Christ Church University. She is also a PhD student in health and well-being. Her research interests are evaluation of research evidence on public health issues, the diagnosis and management of rare long-term conditions, and workplace learning and development in health and social care.

Stephen O’Connor is a reader in cancer, palliative, and end-of-life care in the Faculty of Health and Wellbeing at Canterbury Christ Church University. His work focuses on advanced care planning, evaluation of healthcare innovations in end-of-life care settings, and curriculum development.

Carolyn Jackson is the director of the England Centre for Practice Development in the Faculty of Health and Wellbeing at Canterbury Christ Church University. Her research interests are healthcare policy, workforce modeling, systems leadership, and developing effective workplace cultures.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors received funding from Interreg 2 Seas Mers Zeeen for the research and publication of findings.

References

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Farina N., Daley S., Grosvenor W., Hughes L., Hebditch M., . . . Haq I. (2017). How do we enhance undergraduate healthcare education in dementia? A review of the role of innovative approaches and development of the Time for Dementia Programme. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(1), 68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer L. E. (2017). The role of the music therapist in training caregivers of people who have advanced dementia. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 26(2), 185–199. [Google Scholar]

- Bond J., Stave C., Sganga A., Vincenzino O., O’connell B., Stanley R. L. (2005). Inequalities in dementia care across Europe: Key findings of the Facing Dementia Survey. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 59(s146), 8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker D., Latham I. (2015). Person-centred dementia care: Making services better with the VIPS framework. London, England: Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Buswell M., Lumbard P., Prothero L., Lee C., Martin S., Fleming J., Goodman C. (2014). Unplanned, urgent and emergency care: what are the roles that EMS plays in providing for older people with dementia? An integrative review of policy, professional recommendations and evidence. Emergency Medicine Journal, emermed-2014. Retrieved from https://emj.bmj.com/content/33/1/61?papetoc= [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cooke A., Smith D., Booth A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dening K. H., Greenish W., Jones L., Mandal U., Sampson E. L. (2012). Barriers to providing end-of-life care for people with dementia: a whole-system qualitative study. BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care, 2(2):103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vugt M., Dröes R. M. (2017). Social health in dementia. Towards a positive dementia discourse. Aging and Mental Health, 21(1), 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewing J., Dijk S. (2016). What is the current state of care for older people with dementia in general hospitals? A literature review. Dementia, 15(1), 106–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods M., Cavers D., Agarwal S., Annandale E., Arthur A., Harvey J., . . . Riley R. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(1), 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson D., Sandman P. O., Nay R., Karlsson S. (2009). Predictors of job strain in residential dementia care nursing staff. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(1), 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggenberger E., Heimerl K., Bennett M. I. (2013). Communication skills training in dementia care: A systematic review of effectiveness, training content, and didactic methods in different care settings. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(3), 345–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin E. J., Brotherson M. J., Summers J. A. (2011). Understanding qualitative metasynthesis: Issues and opportunities in early childhood intervention research. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(3), 186–200. [Google Scholar]

- Golden S. H., Hager D., Gould L. J., Mathioudakis N., Pronovost P. J. (2017). A gap analysis needs assessment tool to drive a care delivery and research agenda for integration of care and sharing of best practices across a health system. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 43(1), 18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotts Z. M., Baur N., McLellan E., Goodman C., Robinson L., Lee R. P. (2016). Commissioning care for people with dementia at the end of life: A mixed-methods study. BMJ Open, 6(12), e013554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton C., Murphy K., Brooker D., Casey D. (2016). Healthcare staffs’ experiences and perceptions of caring for people with dementia in the acute setting: Qualitative evidence synthesis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 61, 104–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber M., Knottnerus J. A., Green L., van der Horst H., Jadad A. R., Kromhout D., . . . Schnabel P. (2011). How should we define health? BMJ: British Medical Journal, 343, d4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khachaturian A. S., Hoffman D. P., Frank L., Petersen R., Carson B. R., Khachaturian Z. S. (2017). Zeroing out preventable disability: Daring to dream the impossible dream for dementia care: Recommendations for a national plan to advance dementia care and maximize functioning. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 13(10), 1077–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos P. C., Mitchell G. J., Mistry B., Ballon B. (2010). Using drama to improve person‐centred dementia care. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 5(2), 159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathren C. R., Sloane P. D., Hoyle J. D., Zimmerman S., Kaufer D. I. (2013). Improving dementia diagnosis and management in primary care: A cohort study of the impact of a training and support program on physician competency, practice patterns, and community linkages. BMC Geriatrics, 13(1), 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Sherlock P., McKee M., Ebrahim S., Gorman M., Greengross S., Prince M., . . . Ferrucci L. (2012). Population ageing and health. The Lancet, 379(9823), 1295–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melin Emilsson U. (2009). Health care, social care or both? A qualitative explorative study of different focuses in long-term care of older people in France, Portugal and Sweden. European Journal of Social Work, 12(4), 419–434. [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi M., Nakashima T., Shindo Y., Miyamoto Y., Gove D., Radbruch L., van der Steen J. T. (2015). An evaluation of palliative care contents in national dementia strategies in reference to the European Association for Palliative Care white paper. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(9), 1551–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noblit G. W., Hare R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington H. (2018). Employing meta-ethnography in the analysis of qualitative data sets on youth activism: A new tool for transnational research projects? Qualitative Research, 18(1), 108–130. [Google Scholar]

- Prince M., Guerchet M., Prina M. (2015). The epidemiology and impact of dementia: Current state and future trends. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/dementia/dementia_thematicbrief_epidemiology.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Prince M., Knapp M., Guerchet M., McCrone P., Prina M., Comas-Herrera A., . . . Rehill A. (2014). Dementia UK: Overview. Retrieved from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/59437/1/Dementia_UK_Second_edition_-_Overview.pdf

- Protti D. (2009). Integrated care needs integrated information management and technology. Healthcare Quarterly, 13(Spec No), 24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaglio G., Brand H., Dario C. (2016). Fighting dementia in Europe: The time to act is now. The Lancet Neurology, 15(5), 452–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risco E., Cabrera E., Farré M., Alvira C., Miguel S., Zabalegui A. (2016). Perspectives about health care provision in dementia care in Spain: A qualitative study using focus-group methodology. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 31 (3), 223–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson L., Bamford C., Briel R., Spencer J., Whitty P. (2010). Improving patient-centered care for people with dementia in medical encounters: An educational intervention for old age psychiatrists. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(1), 129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2017). National audit of dementia care in general hospitals 2016-2017: Third round of audit report. Retrieved from Royal College of Psychiatrists: https://www.hqip.org.uk/resources/national-audit-of-dementia-care-in-general-hospitals-2016-2017-third-round-of-audit-report/

- Stange K. C. (2009). The problem of fragmentation and the need for integrative solutions. The Annals of Family Medicine, 7(2), 100–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toye F., Seers K., Allcock N., Briggs M., Carr E., Barker K. (2014). Meta-ethnography 25 years on: Challenges and insights for synthesising a large number of qualitative studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14(1), 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner A., Eccles F. J., Elvish R., Simpson J., Keady J. (2017). The experience of caring for patients with dementia within a general hospital setting: A meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature. Aging and Mental Health, 21(1), 66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2015). World population ageing. New York, NY: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/theme/ageing/WPA2015.shtml

- Van de Voorde C., Van den Heede K., Beguin C., Bouckaert N., Camberlin C., de Bekker P., … Grau C. (2017). Required hospital capacity in 2025 and criteria for rationalisation of complex cancer surgery, radiotherapy and maternity services (No. 289). Retrieved from Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE): http://www.bravo-radiotherapie.be/en/mod_news/required-hospital-capacity-in-2025-and-criteria-for-rationalisation-of-complex-cancer-surgery-radiotherapy-and-maternity-services-1/

- Vedel I., Trouvé H., Jean O. S., Ankri J., Somme D. (2013). Factors facilitating and impairing implementation of integrated care. Revue D'Epidemiologie et de Sante Publique, 61(2), 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Bertalanffy L. (1977). The role of systems theory in present day science technology and philosophy. In Schaefer K. E, Hensel H., Brady R. (Eds), A new image of man in medicine: Proceedings of toward a man-centered medical science symposium (pp. 11–15). Mt Kisco, NY: Futura Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch C. J., Orsulic-Jeras S. (2018). Meeting the informational, educational, and psychosocial support needs of persons living with dementia and their family caregivers. The Gerontologist, 58(suppl_1), S58–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Dementia Council. (2017). Global care statement: Statement on importance of care and support. Retrieved from https://worlddementiacouncil.org/news/wdc-publishes-global-care-statement