Highlights

-

•

Bowel involvement in endometriosis is rare. Cecal endometriosis is seen in just 3.5 % of patients with bowel involvement. Patients with bowel involvement typically also have associated ovarian &/or extra-ovarian pelvic endometriosis. This case is the rarest of rare cases in that the patient had isolated cecal endometriosis without any obvious pelvic disease.

-

•

This is the largest reported size of a cecal endometrioma (8 × 6 cms), to the best of our knowledge.

-

•

Extra-uterine cellular leiomyoma also known as ‘wandering fibroid’ & ‘parasitic leiomyoma’ is again an extremely rare neoplasm. There are very few reported cases of parasitic leiomyoma.

-

•

Another rarest of rare event is the concurrent existence of the 2 above mentioned conditions in the same patient.

Keywords: Concurrent, Isolated large cecal endometrioma, Solitary extra-uterine cellular leiomyoma, Laparoscopy

Abstract

Introduction

Cecal endometriosis is an infrequent cause of right iliac fossa pain. The extra-uterine retroperitoneal cellular leiomyoma is a rare tumor. The concurrent existence of both these rare conditions is a unique event.

Presentation of case

We hereby report the case of a 44-year-old woman who had concurrent large isolated cecal endometrioma, which was diagnosed pre-operatively on imaging to be pelvic endometriosis/hematosalpinx and solitary retroperitoneal cellular leiomyoma, which was incidentally identified. Both the conditions were managed successfully by laparoscopy.

Discussion

Cecal endometriosis is difficult to diagnose pre-operatively as there are far commoner clinical conditions that cause similar signs and symptoms. Often it gets mistaken for these conditions and gets diagnosed incidentally ‘on table’ during surgeries being performed purportedly to treat them.

Conclusion

Although definitive diagnosis can only be obtained after histopathology, laparoscopy can be considered a standard diagnostic modality for both these conditions.

1. Introduction

Endometriosis is the existence of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity. It is fairly common in childbearing women. The most frequent location is the ovary, followed by the pouch of Douglas and the uterosacral ligaments [1]. The bowel is the most affected extragenital location (3–12 %). Among the various bowel endometriosis locations, 50–90 % are at the recto-sigmoid junction. However, it can also affect the small bowel (2–16 %), appendix (3–18 %), and cecum (2–5%) [2]. Endometriosis of the gastrointestinal tract is usually asymptomatic, but symptoms such as abdominal pain, distension, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, dyspareunia, and hematochezia could occur in some cases [3]. These symptoms are more commonly caused by other conditions like appendicitis, Crohn’s disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, intestinal obstruction or malignancies [3]. Endometriosis involves a wide array of clinical presentations. Although chronic lower abdominal pain is its common symptom, patients with endometriosis in unusual sites can present with acute abdominal pain in up to 8% of the cases [4,5].

We herein report a unique case of concurrent isolated large cecal endometrioma and extra-uterine cellular leiomyoma. Both were laparoscopically excised. This study is reported in line with the SCARE criteria [6].

2. Presentation of the case

A 44 year old woman presented to the hospital with chief complaints of severe right iliac fossa pain with loose motions, nausea, vomiting and giddiness since 7 days. She gave a history of chronic dull non radiating lower abdominal pain for the past 6 months for which she had taken symptomatic medicines but to no lasting relief. She had been experiencing inter-menstrual spotting for last two months. She otherwise had a 28-day regular menstrual cycle with moderate, painless periods lasting for 4–5 days. Her last menstrual period was 10 days before her presentation to the hospital.

She had undergone a laparoscopic myomectomy 4 years back. As per available records of the same, she did not have any ovarian or extra-ovarian pelvic endometriosis at that time. On general examination she was a febrile, had a pulse rate of 78 beats/min and her blood pressure was 110/70 mms of Hg. On per abdomen examination, she had tenderness in the lower abdomen. On per vaginal examination, her uterus was anteverted, mobile and normal in size and she had tenderness in the right lateral and posterior vaginal fornices. Also, a firm well defined mass could be felt through her right lateral fornix. Her hemogram revealed a hemoglobin of 11.5 gm%, total leukocyte count of 15400/cu.mm., platelet count of 2.49 lakhs/cu.mm. Her beta human chorionic gonadotropin levels were negative and Serum CA-125 was 75 units per millilitre. An ultrasound scan of the abdomen and pelvis was done and revealed an anteverted, mildly bulky uterus with tiny fibroids. Her endometrial thickness was 6.9 mm and both ovaries were normal. She had a large, thick walled, dumbbell shaped collection in the right adnexa with internal echoes and septations within, measuring 7.6 × 3.8 cm in size. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the pelvis was done subsequently and showed multiple sub serosal and myometrial small fibroids in both the anterior as well as posterior walls of the uterus. A well-defined dumbbell shaped lesion measuring 7.1 × 3.5cms with a thick wall (maximum thickness of 7 mms) and with high proteinaceous content was seen in the right adnexa and appeared to be adherent to a small bowel loop. There was mild free fluid in the pelvis and both the ovaries looked normal (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagnostic imaging. A: USG abdomen showing large thick walled dumbbell shaped collection in the right adnexa with internal echoes and septations within measuring 7.6 × 5 cm in size9 (black arrow); B: MRI pelvis showing dumbbell shaped lesion measuring 7.1 × 5 cm with thick walls (max7 mm) with high proteinaceous content in the right adnexa (black arrow).

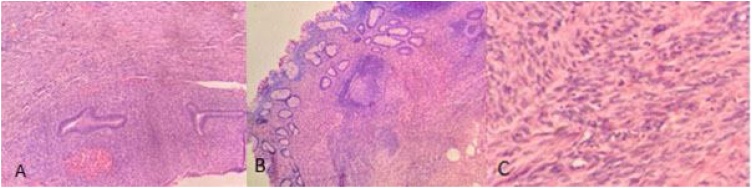

The differential diagnosis as per the imaging investigations was i) pelvic endometriosis, ii) hematosalpinx. She was then taken up for surgery in a tertiary care corporate hospital, by the specialist in gynecologic laparoscopy. At laparoscopy, minimal hemoperitoneum was noted in the pouch of Douglas along with some omental adhesions to the posterior aspect of the uterus, probably at the site of the previous surgery (Fig. 2a). There was no pelvic endometriosis or hematosalpinx (Fig. 2b). She had a large, mobile multi-lobulated mass arising from the cecal wall (Fig. 2c). Also she was incidentally found to have a smaller firm retroperitoneal mass at the level of the pelvic brim on the right side of the midline (Fig. 2d). On noting the above findings, the specialist advanced laparoscopic gastrointestinal surgeon was called in and he performed the rest of the operation. A partial typhlectomy with excision of the mass was then performed using an Endo-GIA linear cutter (Fig. 3a). An active bleeder from the staple line was controlled by an under-running stitch (Fig. 3b and 3c). The smaller retroperitoneal mass was then excised. Both the specimens were retrieved in a plastic bag through the widened hypogastric trocar site (Fig. 4). She had an uneventful post-operative course (Grade 0 as per Clavien-Dindo classification). She was given liquid followed by semisolid feeds per orally starting from postoperative day (POD) 3, which she tolerated well. She was discharged from the hospital on POD 5. On her out patient department follow up visit on POD 10, her wounds had healed completely and she was asymptomatic. The histopathology report revealed, on gross examination, a 1.5 × 1 cm. stretch of cecum and a 8 × 6 cms sized nodular mass with a central cavity, thick fibrous wall and one focus of hemorrhage measuring 2 × 1.5 cms seen in the outer wall. The retroperitoneal mass was firm in consistency, grey in colour and measured 2 × 1.5 cms in size. On microscopic examination, the cecal mass showed a cavity lined by endometrial glands and stroma, suggesting endometrioma (Fig. 5a). At places there was mixed inflammation in the endometrial lining. The mass was adherent to a small part of the cecum but not arising from it. The cecum appeared normal and there was no evidence of malignancy (Fig. 5b). The smaller extra-peritoneal mass turned out to be a cellular leiomyoma (Fig. 5c). She was then administered 11.25 mg of injection Leupride depot (a gonadotropin releasing hormone antagonist).

Fig. 2.

Operative pics. A shows cecal mass (black arrow), hemoperitoneum (red arrow), right adenexa (green arrow); B shows uterine fibroid (black arrow), normal ovary (blue arrow); C shows pedunculated cecal mass (asterisk), cecal attachment of mass (black arrow); D shows retroperitoneal leiomyoma.

Fig. 3.

Operative pics. A shows linear cutter resecting the cecal mass; B shows active bleeder from the staple line; C shows underrunning of the bleeder.

Fig. 4.

Specimen retrieval. A & B show cecal and retroperitoneal masses being ‘bagged’ prior to extraction.

Fig. 5.

Histopathology pics. A – section from cecal mass shows endometrial glands with surrounding stroma in the mass attached to cecum; B shows unremarkable cecal mucosa; C – section from retroperitoneal mass shows smooth muscle bundles without atypia or mitosis.

At the time of writing this paper, a telephonic interview was conducted with her, 5 years after her surgery. She had undergone an ultrasound pelvis and an MRI pelvis 3 and 4 years respectively, after her surgery; on the advice of an infertility specialist whom she was consulting at the time for primary infertility. Both revealed multiple intramural uterine fibroids and no other significant abnormality.

Timeline of events:

| Day | Event |

|---|---|

| 0 | Patient presented with pain in abdomen and diagnosed as pelvic endometriosis/hematosalpinx |

| 1 | Patient underwent laparoscopic resection of cecal mass and retroperitoneal leiomyoma |

| 3 | Patient passed flatus and started on liquids which were tolerated |

| 4 | Patient started on soft diet |

| 5 | Patient had her first bowel movement and was discharged |

| 10 | On first follow up, patient was asymptomatic |

3. Discussion

It has been estimated that 4–17% of all menstruating women have endometriosis [7]; bowel involvement occurs in 3–37% of the cases. Endometriosis of the cecum is seen in just 3.5 % of patients with bowel involvement [8].

Three theories have been proposed to explain the etiopathogenesis of endometriosis – retrograde deposition of endometrial fragments during menstruation, coelomic metaplasia of the peritoneum and spread of endometrial tissue through lymphatics and blood vessels. However the absolute truth still eludes us.

The involvement of the bowel by endometriosis is usually associated with pelvic disease. However in this case, this was not true. None of the available diagnostic procedures (i.e. transvaginal USG, MRI, Doppler ultrasonography, CA-125 levels) help in the preoperative diagnosis. A definitive diagnosis is possible only after histopathological examination of the excised specimen [9]. Endometriosis does not invade the bowel mucosa. Hence it is difficult to diagnose it by endoscopy. As laparoscopy provides a magnified view, it qualifies as a diagnostic modality. But due to varied appearances especially at the unusual sites, the diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopy is very subjective. Unquestionable diagnosis finally requires a histopathological study of the operative specimen.

Extra-uterine cellular leiomyoma also known as ‘parasitic leiomyoma’ or ‘wandering fibroid’, is an extremely rare benign neoplasm. It can have unusual locations and presentations. It is usually not pre-operatively diagnosed on imaging and is diagnosed only on post-operative histopathological study. They are commonly secondary iatrogenic due to seedling during myomectomy or hysterectomy. There are very few reported cases of parasitic leiomyoma. Most of the reported ones are of the secondary iatrogenic type. Gaspare et al. concluded morcellation during hysterectomy as a risk factor in developing parasitic leiomyomas in a retrospective study [10].

A brief review of literature on cecal endometriosis is summarized (Table 1). To the best of our knowledge, this case has the largest reported size of bowel endometriosis, till present day and the only case with the 2 rare concurrent findings.

Table 1.

Summary of review of literature on cecal endometriosis.

| Authors [Ref.no.] | Age of patient/s | Pre-operatively diagnosed (thought to be…) | Uterus-Ovaries(Internal genitalia) | Mode of surgery/Surgery performed | Size | Miscellaneous information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Hamidreza Alizadeh Otaghvar, Mostafa Hosseini et al. [11] | 43y | No(acute appendicitis) | Normal | Open/Right Hemicolectomy | 3 cms | 1 day history of acute right iliac fossa pain,nausea,vomiting, WBC-10900 |

| 2. Ugo Indraccolo, Paolo Trevisan et al. [12] | 36y | Yes, endometriotic nodule at the lead point of ileo-colic intussusception in a known case of extensive long standing endometriosis | Extensively involved, had frozen pelvis | Laparoscopy/Right Hemicolectomy with extensive de-bulking | 2 cms | Known case of endometriosis since age 30,endometriotic nodules on the recto-sigmoid were also removed by opening the posterior vaginal fornix, developed recto-vaginal fistula-underwent diversion colostomy for that, after 3mths, the fistula healed & colostomy was reversed |

| 3. Yi Ying Law, Rhea Patel [13] | 33y | No(marked edema of cecum & ileo-cecal valve on CECT…appendicitis contemplated) | Involved | Laparoscopy/ Right Hemicolectomy with extracorporeal anastomosis |

3.4cm × 3.7cm | CECT also showed thickening of desc.& sigmoid colon, colonoscopic mucosal biopsy revealed ischemic colitis, on HTP 45 nodes in the specimen had endosalpingosis & endometriosis |

| 4. O Baraket, R Zribi et al. [14] | 24y | No(acute appendicitis) | Normal | Open/Right Hemicolectomy | 3 cms | Planned Lap. appendectomy converted to open rt. hemicolectomy |

| 5. Daisuke Ito, Susumu Kaneko et al. [15] | 41y | No(sigmoid volvulus) | Normal | Laparoscopy/Ileo-cecectomy | Short rope like lesion frm cecum till transverse mesocolon around which cecum & asc. colon were twisted | 2 wk history of subacute rt lower abdo pain, CECT-sigmoid volvulus, colonoscopic reduction done-surgery(lap.) done after 2 more wks, HTP study showed endometriosis in the rope like lesion |

| 6. DE Imasogie, PI Agbonrofo et al. [16] | 42y | No(acute small bowel obstruction) | Normal | Open/Rt.Hemicolectomy | 6 × 3 × 3.5 cms hard constricting cecal mass | HTP – cecal endometriosis in submucosa & muscularis propria |

| 7. Ana Lopez Carrasco, Alicia Hernandez Gutierrez et al. [17] | 30−41y(7 cases) | 4-Yes, 3-No | Involved | Laparoscopy(4),SILS(1),Open(2)/all 7 underwent segmental ileal resection, 2 additionally underwent rectosigmoid resection;4 also required combined interventions on internal genitalia(double adnexectomy, ovarian cystectomy, myomectomy, rt. adnexectomy, partial colpectomy and uterosacral ligament resection) | Sizes of the multiple lesions not mentioned in any of the 7 cases, in the paper | 4 diagnosed on MRI + double contrast barium enema,2 on laparoscopy &1 on laparotomy. 4 had partial bowel obstruction,3 had chronic pelvic pain |

| 8. Romina Deldar, Chaitanya Vadlamudi et al. [18] | 33y | No(acute appendicitis) | Normal | Open/Partial cecectomy | 10 cm long distended appendix with firm cecal mass at its base(size not mentioned) | Acute RIF pain,WBC13900-planned Lap appendectomy converted to open partial cecectomy due to intraop suspicion of appendiceal mucinous neoplasm;HTP-acute appendicitis, cecal endometriosis at base of appendix(possibly the cause of acute appendicitis) |

4. Conclusion

The pre-operative diagnosis of cecal endometriosis as well as extra-uterine retroperitoneal cellular leiomyoma is rare and they mostly get diagnosed ‘on table’. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice to rule out a malignant tumor and to prevent complications such as perforation, bowel obstruction and hemorrhage.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Funding

This study did not receive any sources of funding.

Ethical approval

This type of study does not require any ethical approval at our institution.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author’s contribution

1) Umar Riaz: Writing – Original draft, Visualization.

2) Anita Soni: Validation, Supervision.

3) Hetal Parekh: Writing – Review & Editing.

4) Abhijit Joshi: Conceptualization, Validation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration.

Contributor: Sushil Modharkar, M D – Selection & Creation of pictures of the histopathology slides.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Abhijit Joshi.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

Umar Riaz, Email: umarr.riazz1191@gmail.com.

Anita Soni, Email: anita.soni8@hotmail.com.

Hetal Parekh, Email: hetal1233@rediffmail.com.

Abhijit Joshi, Email: asjex1974@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Chapron C., Fauconnier A., Vieira M., Barakat H., Dousset B., Pansini V. Anatomical distribution of deeply infiltrating endometriosis: surgical implications and proposition for a classification. Hum. Reprod. 2003;18:157–161. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teke Z., Aytekin F.O., Atalay A.O., Demirkan N.C. Crohn’s disease complicated by multiple stenoses and internal fistulas clinically mimicking small bowel endometriosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008;14:146–151. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hwang B.J., Jafferjee N., Paniz-Mondolfi A., Baer J., Cooke K., Frager D. Nongynecological endometriosis presenting as an acute abdomen. Emerg. Radiol. 2012;19(5):463–471. doi: 10.1007/s10140-012-1048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown J., Farquhar C. Endometriosis: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009590.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parasar P., Ozcan P., Terry K.L. Endometriosis: epidemiology, diagnosis and clinical management. Curr. Obstet. Gynecol. Rep. 2017;6(1):34–41. doi: 10.1007/s13669-017-0187-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., for the SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muto M.G., O’Neill M.J., Oliva E. A 45-year-old woman with a painful mass in the abdomen. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352(June (24)):2535–2542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc059013. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 18-2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campagnacci R., Perretta S., Guerrieri M., Paganini A.M., De Sanctis A., Ciavattini A., Lezoche E. Laparoscopic colorectal resection for endometriosis. Surg. Endosc. 2005;19(May (5)):662–664. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8710-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muzii L., Bianchi A., Bellati F., Cristi E., Pernice M., Zullo M. Histologic analysis of endometriomas: what the surgeon needs to know. Fertil. Steril. 2007;87:362–366. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaspare C., Roberta G., Gloria C., Edgardo S. Parasitic myomas after laparoscopic surgery: an emerging complication in the use of morcellator? Description of four cases. Fertil. Steril. 2011;96(2):90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otaghvar Hamidreza Alizadeh, Hosseini Mostafa, Shabestanipour Ghazaal, Tizmaghz Adnan, Esfahani Gandom Sedehi. Cecal endometriosis presenting as acute appendicitis. Case Rep. Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/519631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Indraccolo U., Trevisan P., Gasparin P., Barbieri F. Cecal endometriosis as a cause of ileocolic intussusception. J. Soc. Laparoendosc. Surg. 2010;14(January-March (1)):140–142. doi: 10.4293/108680810X12674612015229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law Yi Ying, Patel Rhea, Yorke Rebecca, Bailey Harold R., Van Eps Jeffrey L. A case of infiltrative cecal endometriosis with appendiceal obliteration and lymph node involvement. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020;2020(October (10)):rjaa396. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjaa396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baraket O., Zribi R., Berriche A., Chokki A. Cecal endometriosis as an unusual cause of right iliac fossa pain. J. Postgrad. Med. 2011;57(April-June (2)):135–136. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.81877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito Daisuke, Kaneko Susumu, Morita Kouji, Seiichiro Shimizu, Teruya Masanori, Kaminis Michio. Cecal volvulus caused by endometriosis in a young woman. BMC Surg. 2015;24(June (15)):77. doi: 10.1186/s12893-015-0063-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imasogie D.E., Agbonrofo P.I., Momoh M.I., Obaseki D.E., Obahiagbon I., Azeke A.T. Intestinal obstruction secondary to cecal endometriosis. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018;21(August (8)):1081–1085. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_29_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carrasco Ana López, Gutiérrez Alicia Hernández, Gutiérrez Paula A. Hidalgo, Rodríguez Roberto. Ileocecal endometriosis: diagnosis and management. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;56(April (2)):243–246. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deldar Romina, Vadlamudi Chaitanya, Chen Gao L. Case report: an unusual case of acute appendicitis – cecal endometriosis. Presented at the SAGES 2017 Annual Meeting in Houston, TX. 2017 Abstract ID: 92294, Program Number: PO19. [Google Scholar]