Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) is characterized by degradation of the articular cartilage, synovium inflammation, subchondral bone sclerosis and osteophyte formation. OA is the most common degenerative joint disorder among the elderly population. In particular, currently available therapeutic strategies, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may cause severe side-effects. Therefore, novel candidate targets for OA therapy are urgently needed. Oroxylin A (OrA) is a natural mono-flavonoid that can be extracted from Scutellariae radix. The present study aimed to investigate the potential effects of OrA on interleukin (IL)-1β-induced chondrocytes inflammatory reactions. The current study performed quantitative PCR, western blotting and cell immunofluorescence to evaluate the effect of Oroxylin A in chondrocyte inflammation. The results demonstrated that OrA significantly attenuated the upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase 2 by IL-1β at both protein and mRNA levels. IL-1β-stimulated upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-3 and MMP-13 expression, in addition to disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS)-4 and ADAMTS-5 expression, were all inhibited by OrA. Treatment with OrA significantly reversed the degradation of type II collagen and aggrecan by IL-1β. Mechanistically, OrA suppressed the IL-1β induced activation of ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. In conclusion, these findings suggest that OrA can serve as a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of OA.

Keywords: Oroxylin A, interleukin-1β, osteoarthritis, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common degenerative joint disorder, which leads to chronic bone and muscle pain (1). OA is characterized by degradation of articular cartilage, synovial inflammation, subchondral bone sclerosis and osteophyte formation (2,3). Current strategies for treating OA remain limited and did not seem to improve the management of OA. To date, application of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is the primary therapeutic approach for the treatment of OA (4). However, side-effects, including peptic ulcers, hemorrhage and perforations, frequently occur during the therapeutic process (5,6). Therefore, the development of novel agents for treating OA remain urgently sort after.

OA exhibits several risk factors (7), where the inflammatory mediator interleukin (IL)-1β has been shown to serve an important role in its pathogenesis (8). The adult articular cartilage consists of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and chondrocytes (9). ECM provides the necessary tension and strength to the articular cartilage (10). Under physiological conditions, a subtle balance between ECM synthesis and degradation maintains the homeostasis of the cartilage (11). Previous studies have suggested that IL-1β significantly stimulates chondrocytes to secrete matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (12,13) and promotes the production of inflammatory mediators, including prostaglandin E2 and nitric oxide (NO) (14). It has been suggested that MMPs are responsible for the degradation of ECM during the progression of OA (15). ECM is composed of type II collagen, proteoglycans and aggrecan (16,17). In previous studies, IL-1β has been reported to downregulate the expression of type II collagen and aggrecan in vitro, thereby leading to the degradation of articular cartilage (18,19). Therefore, agents targeting the IL-1β-induced inflammatory response during the pathogenesis of OA can potentially attenuate the progression of OA.

Oroxylin A (OrA) is a natural mono-flavonoid that can be extracted from the herb Scutellariae radix (20). Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that OrA exerts multiple pharmacological effects, including anti-inflammatory (21,22), anti-oxidative (23,24) and anti-tumorigenic (25,26) properties. Therefore, it has been extensively used to treat a variety of diseases. The anti-inflammatory effects of OrA are mainly mediated by blocking the phosphorylation and subsequent activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (27). By contrast, a previous study has also reported that OrA reduces lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory reactions by activating the NF-κB signaling pathway (28). However, the comprehensive role of OrA in OA progression remains poorly understood.

The present study aimed to perform western blotting, qPCR and cell immunofluorescence to evaluate the protective effect of OrA on IL-1β-induced chondrocyte inflammation and its underlying mechanism.

Materials and methods

Reagents

OrA and the Cell Counting Kit (CCK)-8 were purchased from MedChemExpress. Primary antibodies against the unphosphorylated forms of PI3K (cat. no. 4255), AKT (cat. no. 9272), ERK (cat. no. 4695), p38 (cat. no. 14451), JNK (cat. no. 9252), p65 (cat. no. 8242), NF-κB inhibitor α (IκBα; cat. no. 4814), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS; cat. no. 39898), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2; cat. no. 12282) and β-actin (cat. no. 3700), and the phosphorylated (p) forms of AKT (cat. no. 13038), ERK (cat. no. 4370), p38 (cat. no. 9216), JNK (cat. no. 9251), and p65 (cat. no. 3039) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Primary antibodies against MMP3 (cat. no. 17873-1-AP) and MMP13 (cat. no. 18165-1-AP) were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc., whereas those against aggrecan, disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs ADAMTS-4 (cat. no. ab185722), ADAMTS-5 (cat. no. ab41037) and type II collagen (cat. no. ab188570) were from purchased from Abcam. Secondary antibodies (anti-mouse cat. no. 7076 and anti-rabbit cat. no. 7074) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc and diluted in secondary antibody diluent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. P0258; 1:100). DMEM/Ham's F12 medium (DMEM/F12) was obtained from Hyclone, Cytiva. FBS was purchased from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and recombinant rat IL-1β (cat. no. 211-11B) was purchased from PeproTech, Inc.

Isolation and culture of primary chondrocytes

A total of 30 C57BL/6 mice (age, 2-3 days) were purchased from the Animal Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences and were decapitated before chondrocytes were isolated from their articular cartilage. Briefly, the articular cartilages of each mouse were carefully extracted under aseptic conditions and cut into ~1-2 mm2 slices, followed by washing with PBS three times at room temperature. The pieces were then digested using with DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 0.1% collagenase II at 37˚C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 8 h. The cells were then collected via centrifugation at 1,000 x g for 3 min at 25˚C, washed with PBS three times, plated into cell culture flasks in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin and incubated at 37˚C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. The medium was changed after 24 h and the cells were harvested when 80-90% confluence was reached. Only chondrocytes from passages 1-2 were used in the present study to avoid the loss of phenotype. Light microscopy (upper panel original magnification, x100; lower panel original magnification, x200) was performed to observe the cell morphology of chondrocytes. Cells at passages 1-2 had a rounded or polygonal structure.

CCK-8 assay

The primary chondrocytes were plated at a density of 8x103 cells/well into 96-well plates followed by treatment with DMEM/F12 medium containing increasing concentrations of OrA (0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 and 128 µM) at 37˚C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 24 and 48 h. At the end of each time point, 10 µl CCK-8 solution was added into each well and the chondrocytes were incubated further for an additional 4 h at 37˚C in an atmosphere with 95% air and 5% CO2. Absorbance was then measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan™ GO microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

The primary chondrocytes were seeded into six-well plates at a density of 5x105 cells/well. Once they adhered to the plates, chondrocytes were pre-treated with various concentrations of OrA (4, 8, and 16 µM) for 2 h before being stimulated with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) at 37˚C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted using a TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Subsequently, a total of 1,000 ng RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA (PrimeScript™ Reverse Transcriptase kit; Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) using the following temperature protocol: 30˚C for 10 min, 42˚C for 30 min and 70˚C for 15 min, after which the sample was cooled on ice.

RT-qPCR was conducted using the SYBR green Master Mix (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and performed with the ViiA™ 7 real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The thermocycling conditions of qPCR were as follows: 95˚C for 10 min, followed by 50 cycles of 95˚C for 15 sec and 60˚C for 1 min. The cycle threshold (Ct) of each sample was normalized to the expression levels of β-actin. The 2-ΔΔCq method was used to assess the relative expression of various target genes (29). The primer sequences of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-6, iNOS, MMP-3, MMP-13 and β-actin are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Sequences of primers used in reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | 5'-GGAACACGTCGTGGGATAATG-3' | 5'-GGCAGACTTTGGATGCTTCTT-3' |

| IL-6 | 5'-GGCGGATCGGATGTTGTGAT-3' | 5'-GGACCCCAGACAATCGGTTG-3' |

| iNOS | 5'-CAGGGAGAACAGTACATGAACAC3' | 5'-TTGGATACACTGCTACAGGGA-3' |

| MMP-3 | 5'-TTAAAGACAGGCACTTTTGGCG-3' | 5'-CCCTCGTATAGCCCAGAACT-3' |

| MMP-13 | 5'-CTATCCCTTGATGCCATTACCAG-3' | 5'-ATCCACATGGTTGGGAAGTTC-3' |

| β-actin | 5'-AGCCATGTACGTAGCCATCC-3' | 5'-CTCTCAGCAGTGGTGGTGAA-3' |

TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL, interleukin; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Primary chondrocytes (5x104 cells/ml) were seeded into a 12-well plate and were then stimulated at 37˚C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 48 h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 25˚C and washed with PBS. Subsequently, the cell slides were treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature, blocked with 10% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at 25˚C and then incubated with primary antibodies against COX-2 (dilution, 1:500), MMP3 (dilution, 1:500), MMP13 (dilution, 1:500) or type II collagen (dilution, 1:200) at 4˚C overnight. The following day, cells were incubated with fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Abcam; cat. nos. ab150077 and ab150115) diluted in immunofluorescence secondary antibody diluent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. P0265; 1:100) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Subsequently, the cell nuclei were treated with 0.05% DAPI (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. C1002) for an additional 5 min at room temperature in the dark. All images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation). Fluorescence intensity was measured using ImageJ software (v. d1.47; National Institutes of Health).

Western blot analysis

To measure the expression levels of iNOS, COX-2, MMP-3, MMP-13, aggrecan, ADAMTS-4, ADAMTS-5 and type II collagen, a total of 5x105 chondrocytes/well were seeded into six-well plates and pre-treated with various concentrations of OrA (4, 8 and 16 µM) for 2 h, followed by stimulation with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) at 37˚C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 24 h. To explore the molecular mechanism of OrA in the progression of OA, a total of 5x105 chondrocytes/well were seeded into six-well plates, pre-treated with or without 16 µM OrA for 2 h and then stimulated with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for different time periods (0, 15, 30 and 60 min) at 37˚C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Following treatment, total proteins were extracted using a RIPA lysis buffer containing 1% protease and phosphorylase inhibitors (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Proteins were then incubated on ice for an additional 30 min and centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C. Total protein concentration was measured using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). A total of 40 µg of protein from each group was separated using SDS-PAGE on a 10% gel and then transferred onto 0.22-µm PVDF membranes. Following blocking with 5% non-fat dry milk for 2 h at room temperature, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against iNOS, COX-2, MMP3, MMP-13, ADAMTS-4, ADAMTS-5, PI3K, p-AKT, AKT, p-ERK, ERK, p-p38, p38, p-JNK, JNK, p-p65, p65, IκBα, β-actin (all in dilution 1:1,000) or type II collagen (dilution, 1:500) overnight at 4˚C. The membranes were then washed three times with TBS-0.1% Tween-20 for 5 min each time. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with the secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; anti-mouse cat. no. 7076 and anti-rabbit cat. no. 7074) diluted in secondary antibody diluent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. P0258; 1:100) for 2 h at room temperature. The protein bands were visualized by using electrochemiluminescence (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. P0018FS) and captured by a BioSpectrum imaging system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and densitometry analysis was performed using the ImageJ software (v. d1.47; National Institutes of Health).

Animals

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the International Ethical guidelines (30) and the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Pub No 85-23, revised 1996) (31). The procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Ningbo No. 6 Hospital (Ningbo, China).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three experimental repeats. The GraphPad Prism software (version 7.0; GraphPad Software Inc.) was applied for all statistical analyses. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was performed to detect significant differences among groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

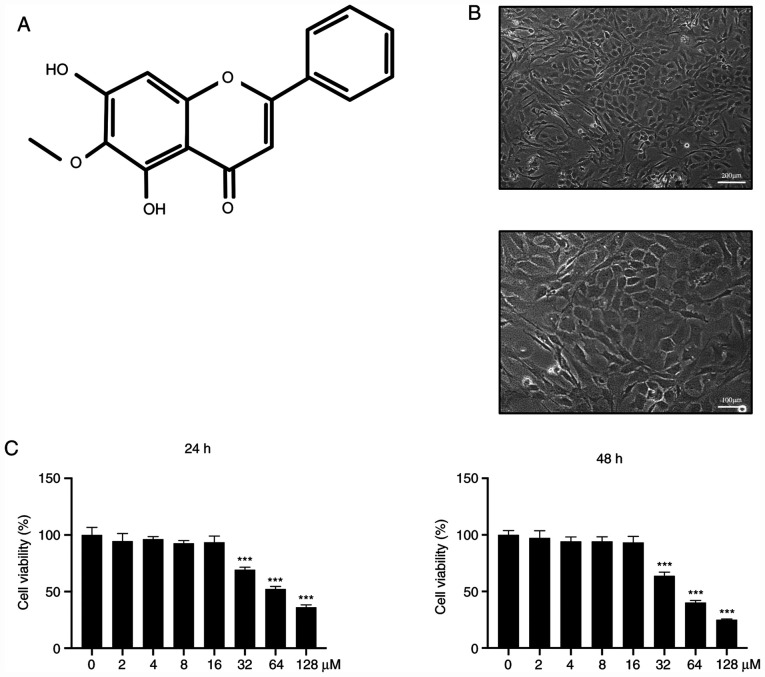

Effects of OrA on murine chondrocyte viability

Chondrocytes were extracted from the articular cartilage of each mice and their morphology was examined. The results revealed that chondrocytes in the cartilage matrix had a rounded or polygonal structure (Fig. 1A). Chondrocytes were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 8x103 cells/well. After adhesion to the dishes, cells were treated with ascending concentrations of OrA (0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128 µM) for 24 and 48 h. The results revealed that OrA at lower concentrations (0, 2, 4, 8, and 16 µM) was not toxic for chondrocytes (Fig. 1B), while the higher concentrations (>32 µM) were toxic for chondrocytes, with the majority of cells dying after stimulation.

Figure 1.

Effect of OrA on murine chondrocyte viability. (A) Chemical structure of OrA. (B) Morphology of chondrocytes (upper panel original magnification, x100; lower panel original magnification, x200). (C) Chondrocytes were treated with medium supplemented with different concentrations of OrA (0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 and 128 µM) for 24 and 48 h before the CCK-8 assay was performed to assess cell viability. Each experiment was repeated three times independently. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. ***P<0.001 vs. untreated. OrA, oroxylin A; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit.

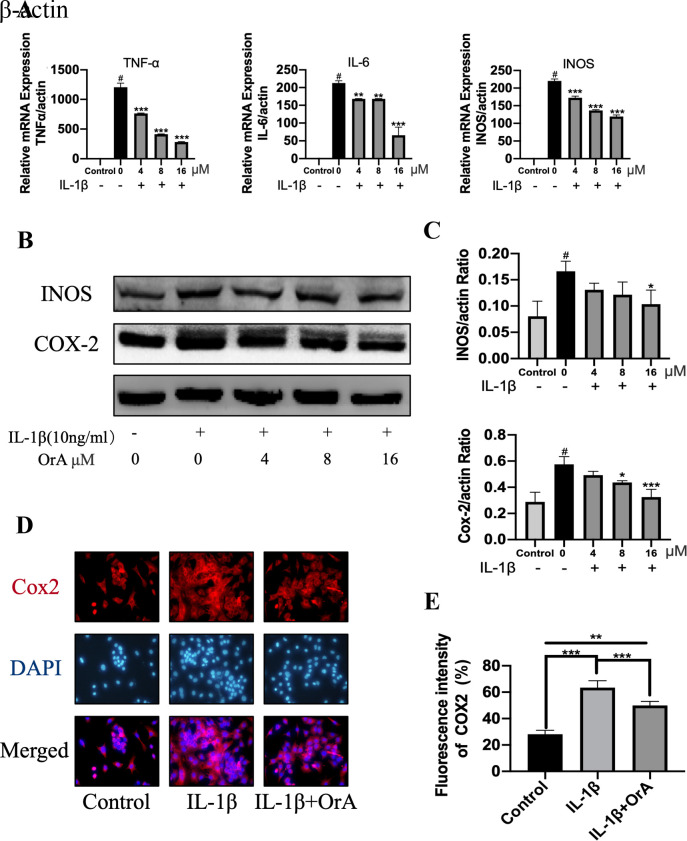

OrA attenuates IL-1β-induced inflammation

The potentially protective effects of OrA against IL-1β-induced inflammatory reaction was next determined by RT-qPCR and western blotting. Although IL-1β significantly promoted the expression of the inflammatory factors TNF-α, IL-6 and iNOS, treatment with OrA significantly reversed this effect in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, western blot analysis revealed that 16 µM OrA markedly inhibited IL-1β-induced upregulation of iNOS and COX-2 (Fig. 2B and C). The protective effects of OrA on IL-1β-induced inflammatory reaction was also supported by results from immunofluorescence analysis. Significantly lower expression levels of COX-2 were observed in cells pre-treated with OrA compared with those in cells treated with IL-1β alone without OrA pre-treatment (Fig. 2D and E).

Figure 2.

OrA attenuates IL-1β-induced inflammation. Chondrocytes were treated with various concentrations of OrA (4, 8, and 16 µM) and stimulated with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. (A) Relative mRNA expression levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and iNOS were determined by reverse-transcription-quantitative PCR. #P<0.01 vs. untreated; **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. IL-1β only. (B) Protein expression levels of iNOS and COX-2 were determined by western blot analysis. (C) Quantification of iNOS and COX-2 expression. #P<0.01 vs. untreated; *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 vs. IL-1β only. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of COX-2 expression, (E) which was quantified. Original magnification, x200. Each experiment was repeated three times independently. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. OrA, oroxylin A; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; COX-2, cyclooxygenase 2.

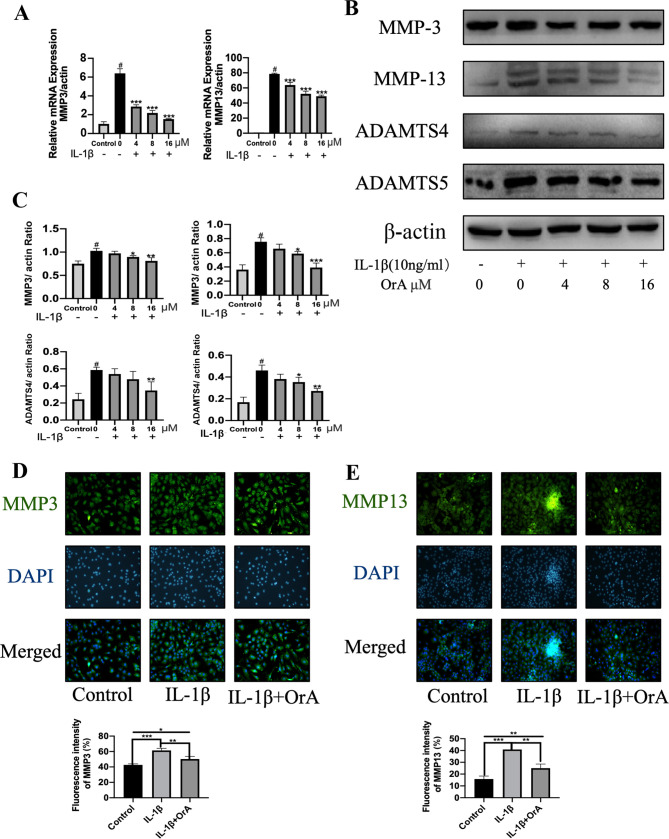

OrA reverses IL-1β-induced degradation of ECM

To explore the effect of OrA on IL-1β-induced degradation of ECM, RT-qPCR was first performed to evaluate the expression levels of the matrix-degrading enzymes MMP-3 and MMP-13. The results demonstrated that OrA significantly attenuated the IL-1β-mediated upregulation of MMP-3 and MMP-13 mRNA (Fig. 3A). The 16 µM OrA-mediated protective effects against IL-1β-induced MMP-3 and MMP-13 upregulation was also confirmed on protein level using western blot analysis (Fig. 3B and C). Consistent with the previous findings of the present study, immunofluorescence results supported the potentially suppressive effects of OrA on IL-1β-mediated increased expression of MMP-3 and MMP-13. Significantly lower expression levels of MMP-3 and MMP-13 were observed in cells pre-treated with OrA compared with those in cells treated with IL-1β alone without OrA pre-treatment (Fig. 3D and E).

Figure 3.

OrA treatment prevents IL-1β-induced degradation of ECM. Chondrocytes were treated with various concentrations of OrA (4, 8 and 16 µM) and stimulated with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. (A) Relative mRNA expression levels of MMP-3 and MMP-13 were determined by reverse transcrtiption-quantitative PCR. (B) The protein expression levels of MMP-3, MMP-13, ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 were determined by western blot analysis. (C) Quantification of MMP-3, MMP-13, ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 expression. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from three experimental repeats. #P<0.01 vs. untreated; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. IL-1β only. Immunofluorescence analysis of (D) MMP-3 and (E) MMP-13 expression, which were quantified (original magnification, x100). Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from three experimental repeats. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. OrA, oroxylin A; ECM, extracellular matrix; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; MMP3, matrix metalloproteinase; ADAMTS, disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs.

The ADAMTS family of metalloproteases has been previously reported to be involved in the cleavage of aggrecan (32). Therefore, the present study investigated the effects of OrA on IL-1β-induced expression of ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5. The results revealed that pre-treatment with 16 µM OrA markedly attenuated IL-1β-mediated upregulation of ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 (Fig. 3B and C).

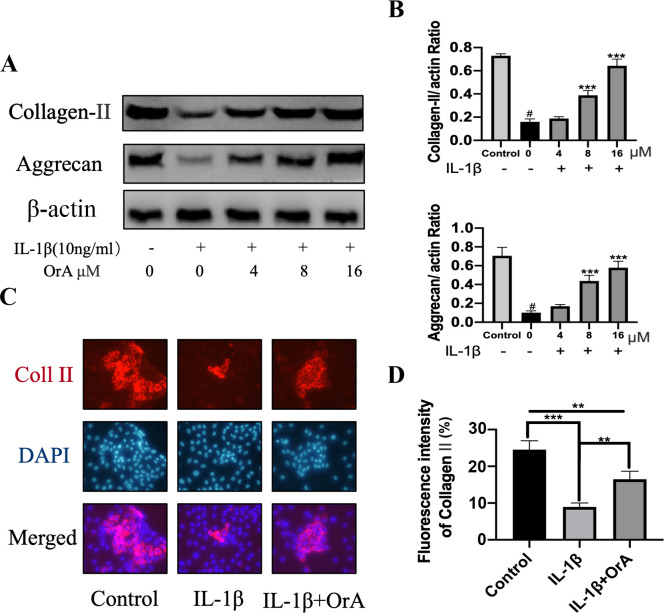

Type II collagen and aggrecan are the main components of ECM (33,34). Treatment with IL-1β significantly decreased the expression of both molecules, whilst pre-treatment with 8 and 16 µM OrA significantly prevented this effect (Fig. 4A and B). Immunofluorescence analysis of type II collagen also indicated that OrA pre-treatment effectively protected against IL-1β-mediated downregulation of type II collagen (Fig. 4C and D).

Figure 4.

OrA reverses IL-1β-induced degradation of ECM. Chondrocytes were treated with various concentrations of OrA (4, 8 and 16 µM) and stimulated with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. (A) Protein expression levels of type II collagen and aggrecan were measured using western blot analysis. (B) Quantification of type II collagen and aggrecan expression from three experimental repeats. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, #P<0.01 vs. untreated; ***P<0.001 vs. IL-1β only. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis of type II collage expression, (D) which was then quantified (original magnification, x200). Each sample was analyzed thrice. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from three experimental repeats. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. OrA, oroxylin A; ECM, extracellular matrix; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; Coll II, collagen II.

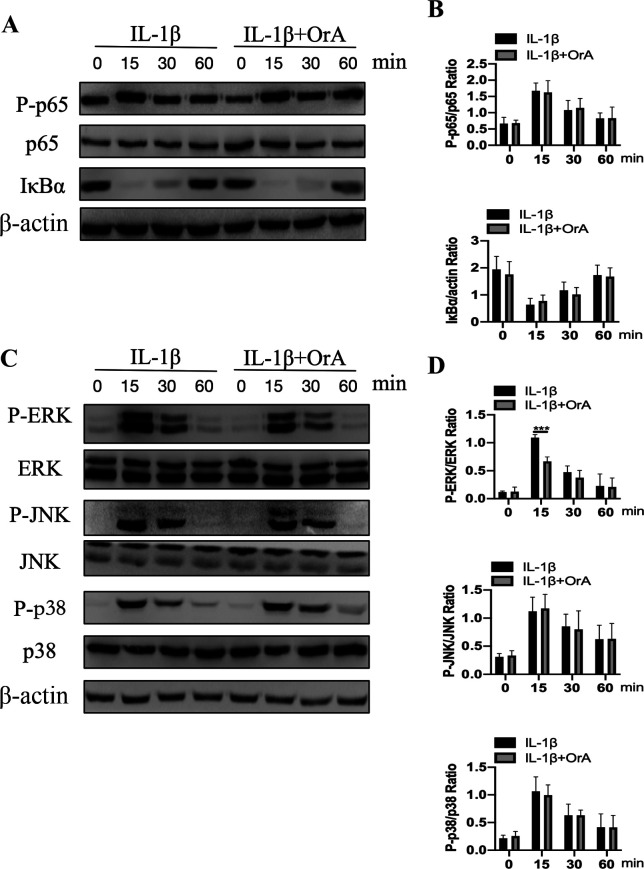

Effect of OrA on IL-1β-induced NF-κ and MAPK activation

Western blot analysis indicated that cell stimulation with IL-1β for 15 min markedly increased the phosphorylation of p65 and IκBα degradation (Fig. 5A and B). However, pre-treatment with OrA had no effects on the NF-κB signaling pathway activation (Fig. 5A and B). The effect of OrA on IL-1β-mediated phosphorylation of ERK, JNK and p38 was subsequently investigated using western blot analysis. Although OrA exerted no effects on the activation of JNK and p38, it significantly prevented the IL-1β-mediated phosphorylation of ERK at 15 min compared with that cells that were not pre-treated with OrA (Fig. 5C and D).

Figure 5.

Effect of OrA on IL-1β-mediated NF-κB and MAPK activation. Chondrocytes were pre-treated with or without 16 µM OrA for 2 h, and then stimulated with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for different time periods (0, 15, 30 and 60 min). (A) The protein expression levels of p65 and IκBα, in addition to p65 phosphorylation were determined by western blot analysis. (B) which was then quantified. (C) The protein expression levels of ERK, JNK, JNK and p38, in addition to their corresponding phosphorylation levels, were determined by western blot analysis and (D) quantified. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from three experimental repeats. ***P<0.001 vs. the IL-1β only group. OrA, oroxylin A; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IκBα, NF-κB inhibitor α; p-, phosphorylated.

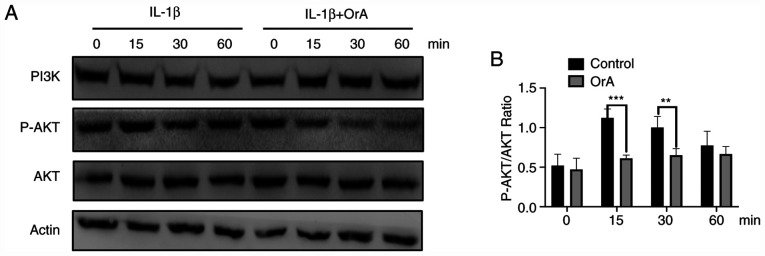

Effect of OrA on IL-1β-mediated PI3K/AKT activation

To further explore the potential anti-inflammatory effects of OrA in chondrocytes, western blot analysis was applied to evaluate the phosphorylation levels of AKT. The results demonstrated that at 15 and 30 min, IL-1β-mediated AKT phosphorylation was significantly lower in chondrocytes pre-treated with OrA compared with cells there were not pre-treated (Fig. 6A and B).

Figure 6.

Effect of OrA on IL-1β-mediated PI3K/AKT activation. (A) Protein expression levels of PI3K and AKT, in addition to AKT phosphorylation, were determined by western blot analysis and (B) quantified. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation from three experimental repeats. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. the IL-1β only group. OrA, oroxylin A; IL-1β, interleukin-1β.

Discussion

OA is a chronic age-associated degenerative joint disease with a complex pathology that imposes severe socio-economic burdens on the patients (35). According to statistics, ~10% men and 13% women aged ≥60 years are afflicted with knee OA in the USA (36). At present, OA treatment strategies for relieving the pain symptoms are limited, where surgery is considered to be the final option in cases of advanced disease progression (37). Although agents are available to clinically relieve pain, severe side effects frequently occur. For instance, NSAIDs, which are used widely in OA to clinically relieve pain and swelling, do not ameliorate cartilage degeneration and are associated with gastrointestinal side effects, such as gastrorrhagia (38,39). Therefore, novel, safe and effective alternative strategies are urgently sorted for OA treatment. OrA is a natural mono-flavonoid that can be extracted from Scutellariae radix (40). Previous studies have reported the anti-inflammatory effects of OrA (21,41). The present study investigated the potential effects of OrA in IL-1β-induced inflammation in murine chondrocytes. The results revealed that OrA pre-treatment resulted in the suppression of inflammation by inhibiting the ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways.

Accumulating evidence has indicated that OA is characterized by cartilage degeneration (42). Under normal conditions, the joint cartilage is maintained through a delicate balance between the synthesis and degradation of ECM (43). However, inflammatory cytokines, especially IL-1β, can perturb this balance, which leads to cartilage degradation (44). In the present study, iNOS and COX-2 were found to be significantly upregulated following stimulation with IL-1β. It has been previously reported that the production of iNOS and COX-2 serves an important role in the pathophysiology of OA (45). Several studies demonstrated that iNOS and COX-2 downregulation ameliorated the progression of OA (46,47). The present findings showed that OrA significantly prevented the IL-1β-induced expression of iNOS and COX-2. ECM is the main component of articular cartilage (48). Increased catabolism of ECM is considered to be a crucial factor in the progression of OA (49). Previous studies have provided evidence that the activation of MMPs, especially MMP3 and MMP13, promotes the degradation of ECM (12,13). In the present study, stimulation with IL-1β markedly upregulated the expression of MMP3 and MMP13, whilst pre-treatment with OrA prevented this effect. Aggrecan and type II collagen are the main components of ECM, such that downregulation of both of these molecules leads to cartilage degradation (50). In the present study, IL-1β significantly attenuated the expression of aggrecan and type II collagen, whilst pre-treatment with OrA prevented this effect. In addition, the ADAMTS enzymes, especially ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5, are considered to be the primary aggrecanases with the ability to cleave aggrecans (51,52). In the present study, treatment with OrA attenuated IL-1β-induced expression of ADAMTS-5 and protected against IL-1β-induced cartilage degradation.

The MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways serve a crucial role in the pathogenesis of OA (53,54). Inhibition of IL-1β-induced activation of ERK has been previously reported to attenuate the progress of OA (55). Accumulating evidence has suggested that the activation of ERK mediates the production of MMPs, thereby promoting cartilage degradation (56,57). The present study demonstrated that treatment with OrA significantly inhibited the activation of ERK. Another previous study reported that inhibition of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway relieved IL-1β-induced inflammatory response in chondrocytes (58). In addition, it has been also reported that PI3K/AKT signaling regulates the expression of aggrecan (59). Therefore, the present study investigated the effect of OrA on IL-1β-mediated activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and confirmed that OrA could also inhibit the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

However, there are still several limitations in the current study. First, as the present research was based on murine chondrocytes, which were obtained from neonatal mice, the mice were not weighed or sexed upon purchase. Additionally, the current study lacks in vivo results, which should be assessed in future work.

Taken together, the results of the present study suggested that OrA exerted protective effects against IL-1β-induced inflammatory response by inhibiting the activation of the ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. The current study indicated the therapeutic potential of OrA in osteoarthritis treatment and may therefore provide a novel candidate for OA therapy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

Funding: The present study was supported by the Medical and Health Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2019PY073); Science and Technology Research on Public Welfare Project of Ningbo, Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2019C50050) and the Scientific Technology Project of Agriculture and Social Development of Yinzhou, Ningbo, Zhejiang Province (grant no. 20180137).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

YZ and QW conceived the study; YZ and JC conducted the experiments; JH wrote the manuscript and performed statistical analysis; QW and ML analyzed the results and created the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the international ethical guidelines and the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Pub No 85-23, revised 1996). The procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Ningbo No. 6 Hospital (Ningbo, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ji Q, Xu X, Kang L, Xu Y, Xiao J, Goodman SB, Zhu X, Li W, Liu J, Gao X, et al. Hematopoietic PBX-interacting protein mediates cartilage degeneration during the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Commun. 2019;10(313) doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08277-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashford S, Williard J. Osteoarthritis: A review. Nurse Pract. 2014;39:1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000445886.71205.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abramson SB. Inflammation in osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2004;70:70–76. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328349c2b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen YF, Jobanputra P, Barton P, Bryan S, Fry-Smith A, Harris G, Taylor RS. Cyclooxygenase-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (etodolac, meloxicam, celecoxib, rofecoxib, etoricoxib, valdecoxib and lumiracoxib) for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2008;12:1–278. doi: 10.3310/hta12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lane NE. Pain management in osteoarthritis: The role of COX-2 inhibitors. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1997;49:20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hungin APS, Kean WF. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Overused or underused in osteoarthritis? Am J Med. 2001;110 (Suppl):S8–S11. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00628-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felson DT. Risk factors for osteoarthritis: Understanding joint vulnerability. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;427:16–21. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000144971.12731.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldring MB, Otero M. Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:471–478. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328349c2b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mokuda S, Nakamichi R, Matsuzaki T, Ito Y, Sato T, Miyata K, Inui M, Olmer M, Sugiyama E, Lotz M, Asahara H. Wwp2 maintains cartilage homeostasis through regulation of Adamts5. Nat Commun. 2019;10(2429) doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10177-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Shehzad O, Ko SK, Kim YS, Kim HP. Matrix metalloproteinase-13 downregulation and potential cartilage protective action of the Korean Red Ginseng preparation. J Ginseng Res. 2015;39:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao Y, Liu S, Huang J, Guo W, Chen J, Zhang L, Zhao B, Peng J, Wang A, Wang Y, et al. The ECM-cell interaction of cartilage extracellular matrix on chondrocytes. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014(648459) doi: 10.1155/2014/648459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang M, Sampson ER, Jin H, Li J, Ke QH, Im HJ, Chen D. MMP13 is a critical target gene during the progression of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(R5) doi: 10.1186/ar4133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubota E, Imamura H, Kubota T, Shibata T, Murakami KI. Interleukin-1 beta and stromelysin (MMP3) activity of synovial fluid as possible markers of osteoarthritis in the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:20–28. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Studer R, Jaffurs D, Stefanovic-Racic M, Robbins PD, Evans CH. Nitric oxide in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1999;7:377–379. doi: 10.1053/joca.1998.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith RL. Degradative enzymes in osteoarthritis. Front Biosci. 1999;4(D704-D712) doi: 10.2741/a388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tchetina EV, Squires G, Poole AR. Increased type II collagen degradation and very early focal cartilage degeneration is associated with upregulation of chondrocyte differentiation related genes in early human articular cartilage lesions. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:876–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vertel BM. The ins and outs of aggrecan. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:458–464. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)89115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding J, Ghali O, Lencel P, Broux O, Chauveau C, Devedjian JC, Hardouin P, Magne D. TNF-alpha and IL-1beta inhibit RUNX2 and collagen expression but increase alkaline phosphatase activity and mineralization in human mesenchymal stem cells. Life Sci. 2009;84:499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Markova D, Anderson DG, Zheng Z, Shapiro IM, Risbud MV. TNF-α and IL-1β promote a disintegrin-like and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type I motif-5-mediated aggrecan degradation through syndecan-4 in intervertebral disc. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:39738–39749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.264549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zou M, Hu C, You Q, Zhang A, Wang X, Guo Q. Oroxylin A induces autophagy in human malignant glioma cells via the mTOR-STAT3-Notch signaling pathway. Mol Carcinog. 2015;54:1363–1375. doi: 10.1002/mc.22212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao J, Hu R, Sun J, Lin B, Zhao L, Sha Y, Zhu B, You QD, Yan T, Guo QL. Oroxylin a prevents inflammation-related tumor through down-regulation of inflammatory gene expression by inhibiting NF-κB signaling. Mol Carcinog. 2014;53:145–158. doi: 10.1002/mc.21958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye M, Wang Q, Zhang W, Li Z, Wang Y, Hu R. Oroxylin A exerts anti-inflammatory activity on lipopolysaccharide-induced mouse macrophage via Nrf2/ARE activation. Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;92:337–348. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2014-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Tong D, Liu J, Chen F, Shen Y. Oroxylin A attenuates cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation by activating Nrf2. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;40:524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han Q, Wang H, Xiao C, Fu BD, Du CT. Oroxylin A inhibits H2O2-induced oxidative stress in PC12 cells. Nat Prod Res. 2017;31:1339–1342. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2016.1244193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou M, Lu N, Hu C, Liu W, Sun Y, Wang X, You Q, Gu C, Xi T, Guo Q. Beclin 1-mediated autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells: Implication in anticancer efficiency of oroxylin A via inhibition of mTOR signaling. Cell Signal. 2012;24:1722–1732. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y, Lu N, Ling Y, Gao Y, Chen Y, Wang L, Hu R, Qi Q, Liu W, Yang Y, et al. Oroxylin A suppresses invasion through down-regulating the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2/9 in MDA-MB-435 human breast cancer cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;603:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi HW, Shin PG, Lee JH, Choi WS, Kang MJ, Kong WS, Kang MJ, Kong WS, Oh MJ, Seo YB, Kim GD. Anti-inflammatory effect of lovastatin is mediated via the modulation of NF-κB and inhibition of HDAC1 and the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in RAW264. 7 macrophages. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41:1103–119. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen YC, Yang LL, Lee TJF. Oroxylin A inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced iNOS and COX-2 gene expression via suppression of nuclear factor-κB activation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:1445–1457. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherwin CM, Christiansen SB, Duncan IJ, Erhard HW, Lay DC, Mench JA, O'Connorg CE, Petherick CJ. Guidelines for the ethical use of animals in applied ethology studies. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2003;81:291–305. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(02)00288-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derrell CJ, Gebhart GF, Gonder JC, Keeling ME, Kohn DF. Special Report: The 1996 Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. ILAR J. 1997;38:41–48. doi: 10.1093/ilar.38.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glasson SS, Askew R, Sheppard B, Carito B, Blanchet T, Ma HL, Flannery CR, Peluso D, Kanki K, Yang Z, et al. Deletion of active ADAMTS5 prevents cartilage degradation in a murine model of osteoarthritis. Nature. 2005;434:644–648. doi: 10.1038/nature03369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poole AR, Kobayashi M, Yasuda T, Laverty S, Mwale F, Kojima T, Sakai T, Wahl C, El-Maadawy S, Webb G, et al. Type II collagen degradation and its regulation in articular cartilage in osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61 (Suppl 2):ii78–ii81. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.suppl_2.ii78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song RH, Tortorella MD, Malfait AM, Alston JT, Yang Z, Arner EC, Griggs DW. Aggrecan degradation in human articular cartilage explants is mediated by both ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;56:575–585. doi: 10.1002/art.22334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glyn-Jones S, Palmer AJR, Agricola R, Price AJ, Vincent TL, Weinans H, Carr AJ. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2015;386:376–387. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60802-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Jordan JM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26:355–369. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarzi-Puttini P, Cimmino MA, Scarpa R, Caporali R, Parazzini F, Zaninelli A, Atzeni F, Canesi B. Osteoarthritis: An overview of the disease and its treatment strategies. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;35:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giercksky KE, Huseby G, Rugstad HE. Epidemiology of NSAID-related gastrointestinal side effects. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;163:3–8. doi: 10.3109/00365528909091168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lichtenberger LM, Zhou Y, Dial EJ, Raphael RM. NSAID injury to the gastrointestinal tract: Evidence that NSAIDs interact with phospholipids to weaken the hydrophobic surface barrier and induce the formation of unstable pores in membranes. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2010;58:1421–1428. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.10.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song X, Chen Y, Sun Y, Lin B, Qin Y, Hui H, Li Z, You Q, Lu N, Guo Q. Oroxylin A, a classical natural product, shows a novel inhibitory effect on angiogenesis induced by lipopolysaccharide. Pharmacol Rep. 2012;64:1189–1199. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(12)70915-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun X, Chang X, Wang Y, Xu B, Cao X. Oroxylin A suppresses the cell proliferation, migration, and EMT via NF-κB signaling pathway in human breast cancer cells. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019(9241769) doi: 10.1155/2019/9241769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roos EM, Arden NK. Strategies for the prevention of knee osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(92) doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luo Y, Sinkeviciute D, He Y, Karsdal M, Henrotin Y, Mobasheri A, Önnerfjord P, Bay-Jensen A. The minor collagens in articular cartilage. Protein Cell. 2017;8:560–572. doi: 10.1007/s13238-017-0377-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonassar LJ, Sandy JD, Lark MW, Plaas AHK, Frank EH, Grodzinsky AJ. Inhibition of cartilage degradation and changes in physical properties induced by IL-1β and retinoic acid using matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;344:404–412. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Needleman P, Manning PT. Interactions between the inducible cyclooxygenase (COX-2) and nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) pathways: Implications for therapeutic intervention in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1999;7:367–370. doi: 10.1053/joca.1998.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.More AS, Kumari RR, Gupta G, Lingaraju MC, Balaganur V, Pathak NN, Kumar D, Kumar D, Sharma AK, Tandan SK. Effect of iNOS inhibitor S-methylisothiourea in monosodium iodoacetate-induced osteoathritic pain: Implication for osteoarthritis therapy. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;103:764–772. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson DJ, Harper SE, Zhao PL, Quan H, Bolognese JA, Simon TJ. Gastrointestinal tolerability of the selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor rofecoxib compared with nonselective COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors in osteoarthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2998–3003. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.19.2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong M, Carter DR. Articular cartilage functional histomorphology and mechanobiology: A research perspective. Bone. 2003;33:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rahmati M, Nalesso G, Mobasheri A, Mozafari M. Aging and osteoarthritis: Central role of the extracellular matrix. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;40:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pattoli MA, MacMaster JF, Gregor KR, Burke JR. Collagen and aggrecan degradation is blocked in interleukin-1-treated cartilage explants by an inhibitor of IκB kinase through suppression of metalloproteinase expression. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:382–388. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.087569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stanton H, Rogerson FM, East CJ, Golub SB, Lawlor KE, Meeker CT, Little CB, Last K, Farmer PJ, Campbell IK, et al. ADAMTS5 is the major aggrecanase in mouse cartilage in vivo and in vitro. Nature. 2005;434:648–652. doi: 10.1038/nature03417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song RH, Tortorella MD, Malfait AM, Alston JT, Yang Z, Arner EC, Griggs DW. Aggrecan degradation in human articular cartilage explants is mediated by both ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:575–585. doi: 10.1002/art.22334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shi J, Zhang C, Yi Z, Lan C. Explore the variation of MMP3, JNK, p38 MAPKs, and autophagy at the early stage of osteoarthritis. IUBMB Life. 2016;68:293–302. doi: 10.1002/iub.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chow YY, Chin KY. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Mediators Inflamm. 2020;2020(8293921) doi: 10.1155/2020/8293921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gao SC, Yin HB, Liu HX, Sui YH. Research progress on MAPK signal pathway in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Zhongguo Gu Shang. 2014;27:441–444. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu Z, Cai H, Zheng X, Zhang B, Xia C. The involvement of mutual inhibition of ERK and mTOR in PLCγ1-mediated MMP-13 expression in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:17857–17869. doi: 10.3390/ijms160817857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hashizume M, Mihara M. High molecular weight hyaluronic acid inhibits IL-6-induced MMP production from human chondrocytes by up-regulating the ERK inhibitor, MKP-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;403:184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xue JF, Shi ZM, Zou J, Li XL. Inhibition of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway promotes autophagy of articular chondrocytes and attenuates inflammatory response in rats with osteoarthritis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;89:1252–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheng CC, Uchiyama Y, Hiyama A, Gajghate S, Shapiro IM, Risbud MV. PI3K/AKT regulates aggrecan gene expression by modulating Sox9 expression and activity in nucleus pulposus cells of the intervertebral disc. J Cell Physiol. 2009;221:668–676. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.