SUMMARY

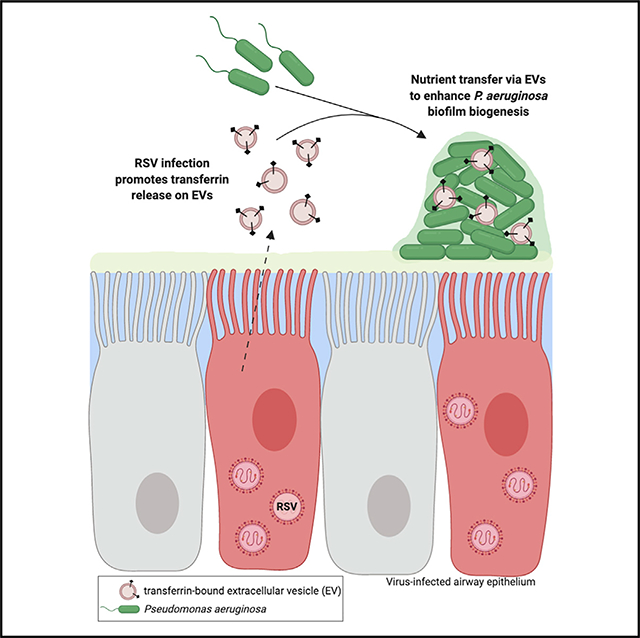

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are increasingly appreciated as a mechanism of communication among cells that contribute to many physiological processes. Although EVs can promote either antiviral or proviral effects during viral infections, the role of EVs in virus-associated polymicrobial infections remains poorly defined. We report that EVs secreted from airway epithelial cells during respiratory viral infection promote secondary bacterial growth, including biofilm biogenesis, by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) increases the release of the host iron-binding protein transferrin on the extravesicular face of EVs, which interact with P. aeruginosa biofilms to transfer the nutrient iron and promote bacterial biofilm growth. Vesicular delivery of iron by transferrin more efficiently promotes P. aeruginosa biofilm growth than soluble holo-transferrin delivered alone. Our findings indicate that EVs are a nutrient source for secondary bacterial infections in the airways during viral infection and offer evidence of transkingdom communication in the setting of polymicrobial infections.

In Brief

Using cystic fibrosis as a model to study mechanisms governing viral-bacterial interactions in the lung, Hendricks et al. report that extracellular vesicles released from the respiratory epithelium during acute viral infections are a nutrient source for bacterial co-infections and offer evidence of transkingdom communication in the setting of polymicrobial infections.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Extracellular communication is a critical component of many host processes. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are small, membrane-enclosed vesicles produced by most cell types and secreted into the extracellular environment. Biologically active proteins, RNAs, and lipids can be packaged into EVs and delivered to target cells, where they affect many biological processes (Lo Cicero et al., 2015). EVs derived from cells are divided into three categories: exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies. Exosomes have been isolated from lung epithelial cells, as well as from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and sputum collected from patients with chronic lung diseases, such as asthma and cystic fibrosis (CF) (Admyre et al., 2003; Kesimer et al., 2009; Moon et al., 2014; Szul et al., 2016; Torregrosa Paredes et al., 2012). Although EVs participate in both normal tissue homeostasis and the progression of inflammation in the airways, little is known about how EVs contribute to bacterial, fungal, or viral infections in the respiratory tract (Fujita et al., 2015).

Previous work on the function of EVs during microbial infections has largely focused on functions of exosomes in the context of virus infections, where they have been reported to both promote and suppress viral infections (Raab-Traub and Dittmer, 2017). For example, replication-competent viral RNA has been observed in exosomes released by hepatitis C (HCV)-infected cells (Bukong et al., 2014; Ramakrishnaiah et al., 2013). During enterovirus 71 (EV71) infection, exosomes have also been shown to promote viral replication by suppressing antiviral immunity (Fu et al., 2017). The converse has also been reported; exosomes isolated from interferon alpha (IFN-α)-treated cells are capable of transferring IFN-α-induced antiviral immunity between cells (Li et al., 2013) and can contain microRNAs (miRNAs) that inhibit viral infection (Delorme-Axford et al., 2013). However, viral infections do not often occur in isolation, and there is an increasing appreciation for the prevalence and severity of polymicrobial infections involving viruses, yet the role EVs have in virus-associated polymicrobial infections remains unexplored.

Studies of viral-bacterial co-infections in the respiratory tract have revealed many interactions by which a preceding virus infection renders the host environment more susceptible to secondary bacterial infection. One such mechanism is by respiratory virus infections that increase bacterial adherence to host airway epithelial cells (AECs) (Avadhanula et al., 2007; Hament et al., 2005; Li et al., 2015; Novotny and Bakaletz, 2016; Smith et al., 2014; van Ewijk et al., 2008). Previous studies have also focused on how preceding respiratory viral infection subverts antibacterial immune defenses in the airways (Rynda-Apple et al., 2015). Emerging work suggests that nutritional immunity is another important process disrupted during viral-bacterial co-infections in the respiratory tract. For example, preceding influenza virus infection increases the availability of host-sialylated mucins leading to increased Streptococcus pneumoniae growth (Siegel et al., 2014), and we have shown that preceding respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) disrupts nutritional immunity in AECs and increases iron release from cells, which enhances Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm growth (Hendricks et al., 2016). Despite these advances, the mechanism by which nutrients are transferred between the host and pathogen during viral-bacterial co-infection is poorly understood.

To test the hypothesis that EVs mediate transkingdom communication and nutrient transfer during co-infection, we used a model of RSV-P. aeruginosa co-infection. P. aeruginosa is a commonly isolated bacterial pathogen in the lungs of patients with chronic lung disease, where it forms chronic, highly antibiotic-resistant, biofilm-associated infections (Bjarnsholt et al., 2009; Singh et al., 2000). Despite clinical studies linking respiratory viral infection with the development of bacterial infections in patients with CF (Collinson et al., 1996; Johansen and Høiby, 1992) and other chronic lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (George et al., 2014) and asthma (Kloepfer et al., 2014), very little is known about transkingdom interactions between viruses and bacteria in chronic lung diseases. Using CF lung disease as a model in the current study, we show that EVs released during virus co-infection mediate nutrient transfer between the host and P. aeruginosa by interacting and promoting P. aeruginosa growth and transition to a biofilm lifestyle. Our results demonstrate that the release of EVs in the respiratory tract during viral infections is an important nutritional factor that dictates the outcome of polymicrobial infections.

RESULTS

EVs secreted from AECs during virus infection stimulate P. aeruginosa biofilm biogenesis

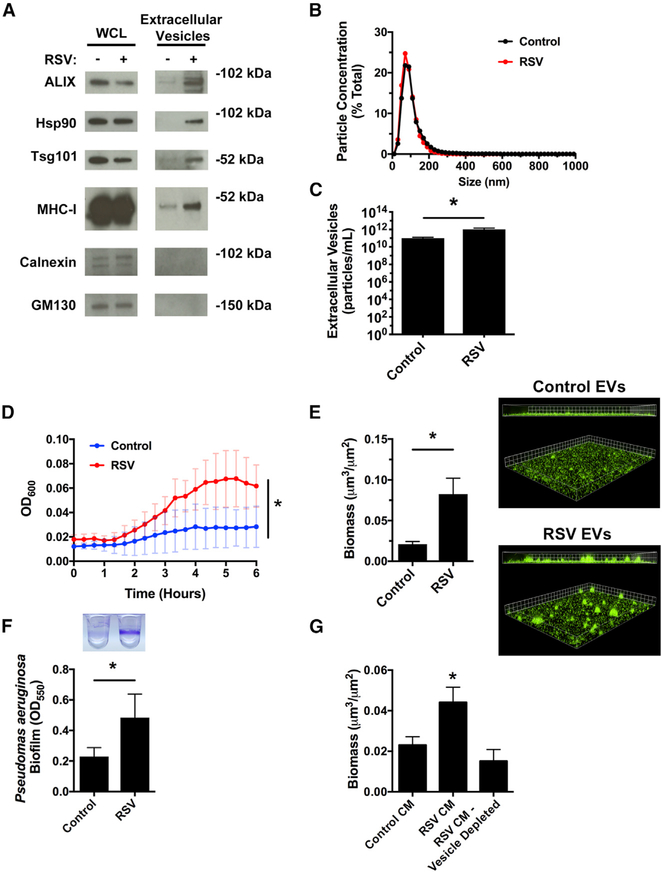

To examine whether EVs contribute to transkingdom interactions between bacteria and the host during viral-bacterial co-infection, we first determined whether EVs produced by uninfected and virus-infected AECs had similar molecular and physical characteristics as EVs previously isolated from the airways. Western blot analysis for standard protein markers of EVs (Figure 1A), nanoparticle tracking analysis (Figures 1B and 1C), and electron microscopy (Figure S1A) were used to confirm that the isolated EVs were of similar composition, size, and morphology as previously reported in the literature for AEC-derived EVs (Chahar et al., 2018; Kesimer et al., 2009; Moon et al., 2014; Szul et al., 2016). We next compared the growth of P. aeruginosa in the presence of EVs released from uninfected and virus-infected AECs. Performing growth curves in minimal media with EVs as the nutrient source, we determined that EVs from RSV-infected AECs significantly enhanced P. aeruginosa growth, as compared with EVs from uninfected cells (Figure 1D). To determine whether this was specific to planktonic growth or whether RSVs were also capable of enhancing P. aeruginosa biofilm growth, we measured P. aeruginosa biofilm growth in an abiotic biofilm assay. EVs from RSV-infected cells significantly increased biofilm growth, in comparison with EVs from uninfected AECs, as measured by fluorescent microscopy and 96-well microtiter biofilm assays (Figures 1E and 1F). Moreover, we observed that RSV infection increased the release of EVs from AECs, as assessed by western blot (Figure 1A) and nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA; Figure 1C). The biofilm-stimulatory activity of EVs isolated from RSV-infected cells was dose dependent and could be diluted to levels observed with EVs isolated from uninfected AECs (Figure S1B), suggesting that increased EV release during RSV infection promotes P. aeruginosa biofilm growth.

Figure 1. EVs from RSV-infected cells increase P. aeruginosa planktonic and biofilm growth.

AECs were infected with RSV or mock infected (MEM control) for 72 h, and EVs were isolated from the apical secretions of cells.

(A and B) RSV infection increases EV secretion from AECs.

(A) EVs were characterized by western blot analysis for standard protein markers of EVs.

(B) RSV infection does not alter the size distribution of EVs released by AECs as analyzed by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA). Histogram displaying the size distribution of purified EVs.

(C) RSV infection increases EV release from AECs. EV concentration was analyzed by NTA.

(D) Bacterial growth curves were performed to measure planktonic growth of P. aeruginosa in the presence of EVs collected from AECs.

(E) P. aeruginosa (GFP, green) was grown in the presence of EVs in static abiotic biofilm assays (grid unit = 8 μM).

(F) P. aeruginosa biofilms were grown in the presence of EVs in 96-well microtiter biofilm assays.

(G) AECs were infected with RSV or mock infected (MEM control) for 72 h and apical CM was collected. CM was depleted of EVs by ultracentrifugation, and P. aeruginosa biofilms were grown in static abiotic biofilm assays.

Control, EVs from mock-infected AECs; RSV, EVs from RSV-infected AECs. For all experiments, n ≥ 3. Data are presented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05 versus control.

The physical and chemical characteristics of EVs bear a resemblance to those of enveloped viruses, and during virus infection, diverse subpopulations of EVs are released by cells, ranging from infectious virus particles to virally induced EVs that contain viral components to EVs consisting entirely of host molecules (Nolte-’t Hoen et al., 2016). Although EVs in our study contained some RSV proteins (Figure S1D), the EV population we isolated did not contain infectious viral particles (Figure S1E). These data suggest that infectious RSV particles are not responsible for the biofilm stimulatory activity of EVs isolated from RSV-infected AECs and are consistent with our previous observations that purified RSV does not stimulate P. aeruginosa biofilm formation (Hendricks et al., 2016). To examine whether EV-mediated P. aeruginosa biofilm growth was specific to RSV infection, we isolated EVs from AECs infected with another respiratory virus commonly found in patients with CF, human rhinovirus (hRV). Interestingly, we observed that EVs isolated from hRV-infected cells also increased P. aeruginosa biofilm growth, although rhinovirus did not increase EV release from AECs (Figures S1F–S1H). Because EVs isolated from AECs infected with disparate viruses stimulated P. aeruginosa biofilm growth, we next assessed whether IFN signaling also increases the biofilm stimulatory activity of EVs. We treated AECs with poly(I:C), which stimulates IFN production and signaling and then measured biofilm growth in the presence of EVs isolated from poly(I:C)-stimulated AECs. We found that poly(I:C) stimulates type I (IFN-β) and III (IFN-λ) production by AECs (Figure S1I), and EVs isolated from poly(I:C)-treated AECs increase P. aeruginosa biofilm growth (Figure S1J). Taken together, these data suggest that the innate immune response to virus infection, at least in part, mediates EV-stimulated biofilm growth.

We previously observed that the apical secretions collected from RSV-infected AECs (hereafter called “conditioned media” [CM]), contained an increased concentration of iron and were capable of enhancing P. aeruginosa biofilm growth (Hendricks et al., 2016). To determine whether EVs were required for CM-mediated bacterial biofilm formation, we used differential centrifugation to deplete EVs from RSV CM and measured biofilm formation. CM from RSV-infected cells that had been depleted of EVs by ultracentrifugation was unable to stimulate P. aeruginosa biofilm growth (Figure 1G), suggesting that EVs are required for virus-induced P. aeruginosa biofilm growth. Additionally, we filtered CM through 100-kDa filters, which would trap any large protein complexes or EVs but allow smaller, soluble proteins and ions to flow through. We observed that the >100-kDa fraction from RSV-infected cells maintained the ability to increase biofilm growth, similar to CM from RSV-infected cells that had not been filtered (Figure S1K). However, the <100-kDa filtrate fraction did not retain biofilm stimulatory activity (Figure S1K). These results demonstrate that EVs from RSV-infected AECs are necessary for the observed virus-stimulated bacterial growth, signifying that host-derived EVs mediate transkingdom interactions between bacteria and viruses in the airways.

EVs localize with P. aeruginosa biofilms

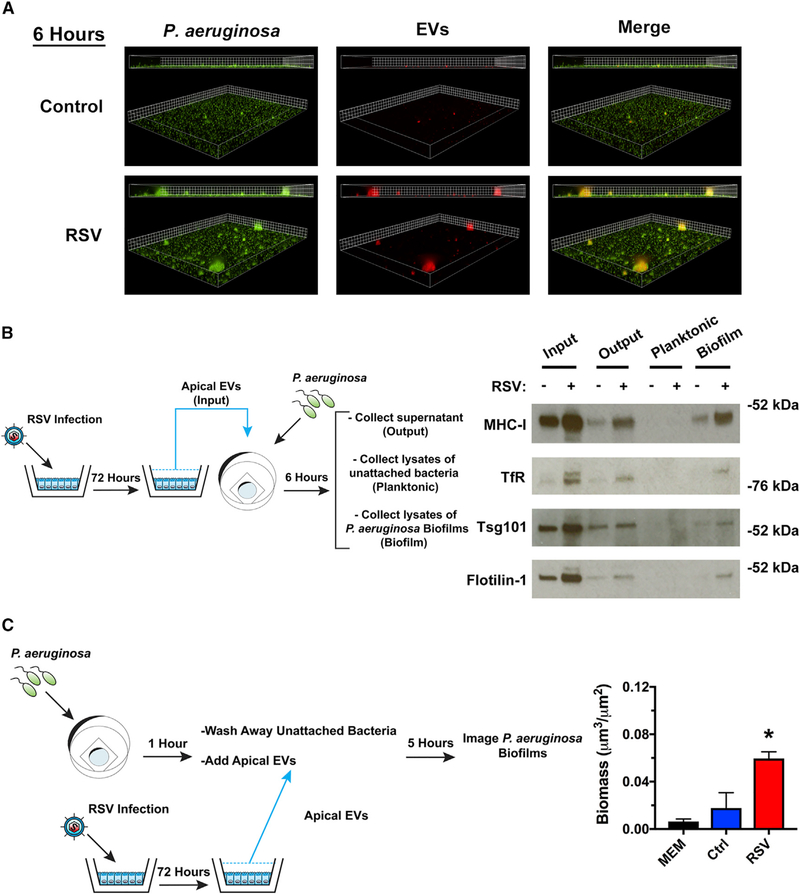

A common function of EVs is to deliver biological molecules to modify the phenotype of recipient cells. We next examined whether EVs interact with P. aeruginosa in biofilms. To track EV interactions with biofilms, we labeled host AECs with CellTracker Deep Red, a fluorescent dye that labels the cytoplasm of cells, as well as the lumen of released EVs (Figure S2A). Using the fluorescently labeled EVs, we examined whether EVs associated with P. aeruginosa biofilms in the presence or absence of virus infection. We observed association of fluorescently labeled EVs from RSV-infected cells with P. aeruginosa biofilms in a time-dependent manner (Figures 2A and S2C). Non-specific aggregation of labeled EVs is not observed in the absence of bacteria (Figure S2B). To further assess the interaction of host-derived EVs with P. aeruginosa biofilms, we examined whether host proteins can be detected in biofilms. We performed static abiotic biofilm assays with EVs, vigorously washed the bacterial biofilms, and measured EV association with P. aeruginosa biofilms by western blot analysis. Interestingly, we observed the presence of host vesicular proteins on biofilms (Figure 2B). These results are consistent with the conclusion that EVs from RSV-infected cells associate with P. aeruginosa biofilms.

Figure 2. RSV EVs localize with P. aeruginosa biofilms and increase growth of surface-associated P. aeruginosa.

(A) EVs isolated from RSV-infected AECs associate with P. aeruginosa biofilms. AECs were infected with RSV or were mock infected (MEM control) for 48 h. Cells were labeled with CellTracker Deep Red Dye for 45 min, and EVs were collected from dye-labeled cells 24 h later. P. aeruginosa (GFP, green) was grown in the presence of EVs (CellTracker Deep Red, red) for 6 h in static abiotic biofilm assays (grid unit = 5 μM).

(B and C) EVs were isolated from AECs infected with RSV or mock infected (MEM control) for 72 h.

(B) EVs associate with surface associated biofilms in static abiotic biofilm assays, as measured by western blot analysis. EV protein abundance was assessed in (1) EVs before (input) static abiotic biofilm assays, (2) EVs collected after (output) static abiotic biofilm assays, (3) planktonic bacteria collected off the top of static abiotic biofilm assays and washed 2× (planktonic), and (4) in surface-associated bacteria washed 2× (biofilm). The schematic outlines experimental design and the fractions analyzed by western blot analysis.

(C) EVs from RSV-infected AECs increase the growth of surface associated P. aeruginosa. Schematic outlines experimental design. Briefly, P. aeruginosa was given 1 h to attach to glass-bottom dishes. Surface-associated bacteria were grown in the presence of EVs for 5 h in static abiotic biofilm assays.

Control, EVs from mock-infected AECs; RSV, EVs from RSV-infected AECs. For all experiments, n ≥ 3. Data are presented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05 versus control.

To examine the mechanism by which RSV EVs stimulate P. aeruginosa biofilm growth, we next investigated whether EVs from RSV-infected AECs increase bacterial surface attachment. We found that there was no difference in bacterial attachment in the presence of EVs isolated from uninfected or RSV-infected cells on either abiotic or biotic surfaces (Figures S2C and S2D). Because EVs from RSV-infected cells did not increase bacterial attachment, we hypothesized that an increased growth of surface-associated bacteria accounted for the observed, enhanced biofilm growth. To measure the effect of EVs on surface-associated growth, we allowed P. aeruginosa to attach to glass-bottom dishes in minimal media, washed away unattached bacteria, and then added EVs to surface-attached bacteria. We observed that surface associated bacterial growth was increased in the presence of RSV EVs, as measured by fluorescent microscopy (Figure 2C). Together, these results indicate that EVs isolated from RSV-infected AECs associate with biofilms, delivering factors, potentially, nutrients, used by P. aeruginosa to promote biofilm biogenesis.

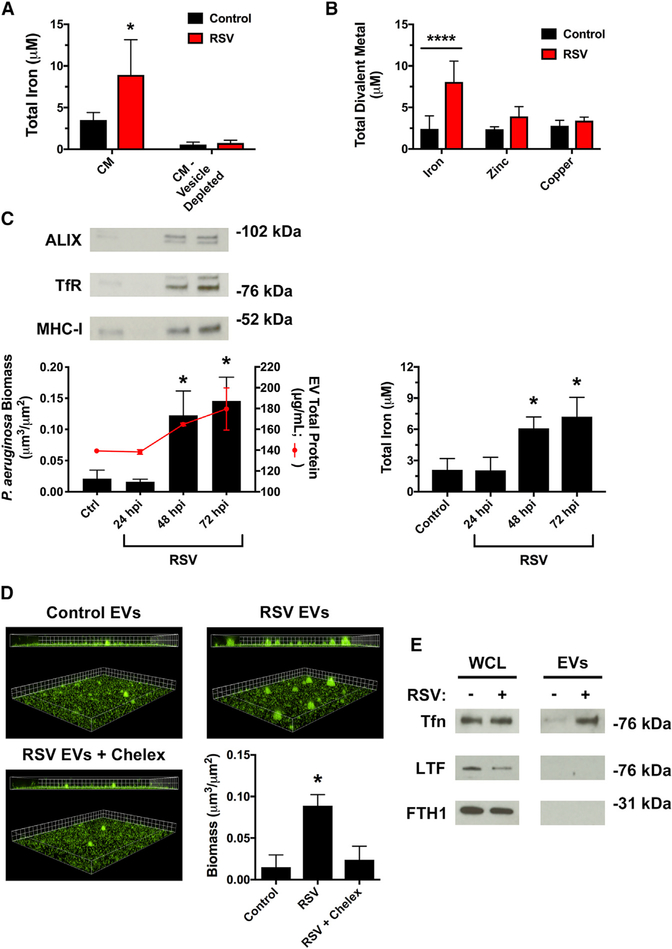

RSV infection increases iron bioavailability on EVs to promote biofilm growth

Iron is required for many biological processes, including P. aeruginosa biofilm growth (Banin et al., 2005; Moreau-Marquis et al., 2008; Patriquin et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2002). We have previously observed that RSV infection increases extracellular iron in CM collected from AECs (Hendricks et al., 2016). However, it is not known whether iron and other metals are loaded onto EVs released by the respiratory epithelium. We observed that iron levels could be significantly reduced in CM by depleting CM of EVs by ultracentrifugation (Figure 3A), suggesting that iron is released on EVs during RSV infection. In agreement with this observation, we observed an increase in total iron on EVs isolated from RSV-infected AECs compared with control EVs (Figure 3B). This effect was specific for iron, as RSV infection did not increase other divalent metal cations, including zinc and copper (Figure 3B). RSV infection increased EV biofilm stimulatory activity and release of iron in EVs in a time-dependent manner, concurrently peaking at 72 h after RSV infection (Figure 3C). Interestingly, hRV infection and poly(I:C) treatment do not increase total iron in EVs (Figure S3A), suggesting that additional mechanisms may also govern EV-stimulated biofilm growth by P. aeruginosa. Importantly, in the setting of RSV co-infection, the presence of iron is necessary for EV-mediated P. aeruginosa biofilm growth because chelation of iron, using the chelating agent Chelex-100, significantly reduced biofilm formation in the presence of EVs from RSV-infected cells (Figure 3D). NTA was performed after Chelex-100 treatment to verify that EV abundance or morphology was not changed by iron chelation (Figure S3B).

Figure 3. RSV infection increases iron associated with EVs to stimulate biofilm growth.

(A and B) RSV infection increases iron association with EVs. Cells were infected with RSV or mock-infected (MEM control) for 72 h. The abundance of divalent metals was measured in (A) CM and CM depleted of EVs by ultracentrifugation or (B) EVs.

(C) P. aeruginosa (GFP) was grown in static abiotic biofilm assays in the presence of EVs isolated from AECs infected with RSV for the indicated number of hours. Protein and total iron were analyzed in EVs isolated at the indicated hours post RSV infection (hpi).

(D) Iron in EVs is required for the growth of P. aeruginosa biofilms. EVs were isolated from AECs infected with RSV or mock infected (MEM control) for 72 h, and static abiotic biofilm assays were performed to measure P. aeruginosa (GFP) biofilms (grid unit = 8 μM). Divalent metal cations were chelated with Chelex-100 resin (labeled “Chelex”) for 1 h. Chelex-100 was removed from EVs by centrifugation at 11,000 × g for 3 min prior to biofilm assays.

(E) RSV infection increases transferrin abundance in EVs, as measured by western blot analysis.

Tfn, transferrin; LTF, lactoferrin; FTH1, ferritin. Control, EVs from mock-infected AECs; RSV, EVs from RSV-infected AECs. For all experiments, n ≥ 3. Data are presented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05 versus control.

Because RSV infection increases iron abundance in EVs and we have previously observed that RSV infection increases transferrin (Tfn) release from AECs (Hendricks et al., 2016), we next examined whether RSV infection alters the host iron-binding protein composition of EVs released by AECs. We found that RSV infection increased transferrin abundance in EVs, as assessed by western blot analysis (Figure 3E). To test the specificity of this response for transferrin, we evaluated two other iron-binding proteins, lactoferrin or ferritin, and observed that EVs from control or RSV-infected AECs did not contain these iron-binding proteins (Figure 3E). Because we observed a higher abundance of EV-associated markers in addition to transferrin (Figure 3E) during RSV infection, which is consistent with increased EV release during virus infection (Figure 1C), our results suggest that RSV infection increases production of transferrin-containing EVs during virus RSV infection. Collectively, these data suggest that RSV infection increases iron bioavailability in host-derived EVs and EV-associated transferrin is a source of iron that promotes the formation of P. aeruginosa biofilms during RSV co-infection.

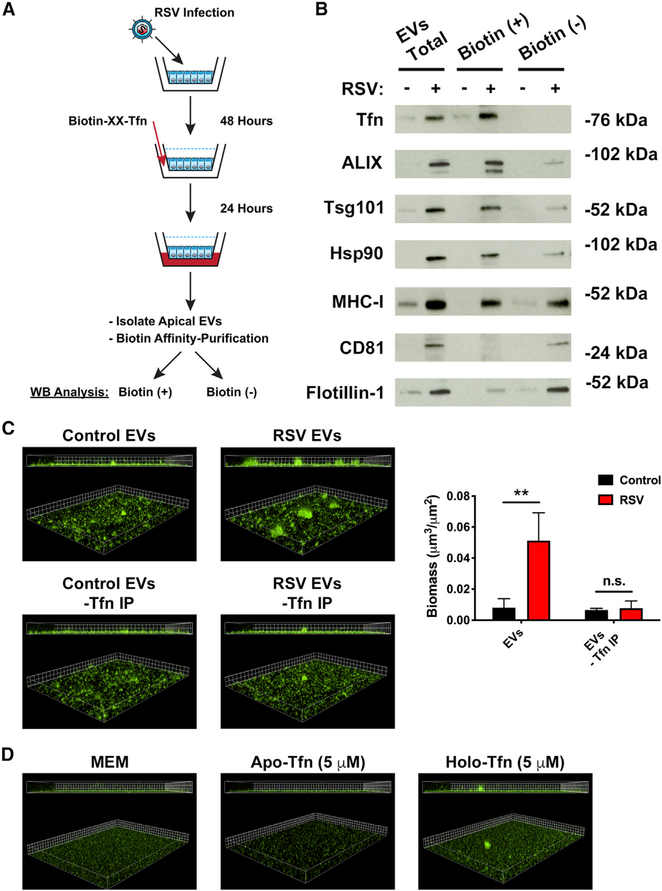

RSV infection increases association of transcytosed transferrin with EVs

Our data suggest a model in which virus infection releases an increased abundance of EVs loaded with transferrin into the apical compartment of cells where it is accessible to bacterial pathogens. However, transferrin is primarily a serum glycoprotein, delivered to cells by the circulatory system, which is taken up and recycled at the basolateral membrane of cells. Thus, we hypothesized that transferrin in the basolateral compartment of cells is transcytosed to the apical compartment during virus infection. We determined whether basolateral transferrin is transcytosed to the apical compartment of cells during virus infection by adding biotinylated transferrin to the basolateral media of RSV-infected cells and then used biotin affinity-purification to isolate transcytosed transferrin in apical compartment EVs (Figure 4A). We observed that significantly more biotinylated transferrin was released in association with EVs during RSV infection compared with uninfected conditions (Figure 4B). This implies that transferrin loaded onto EVs originates in the basolateral compartment. We confirmed this observation by adding fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated transferrin to the basolateral compartment of AECs during RSV infection and probing EVs for FITC fluorescence (Figure S4A). Additionally, we observed that there was no transferrin associated with the biotin-negative fraction, suggesting that all transferrin localized to the EVs originated from the basolateral compartment (Figure 4B). This result is consistent with Chelex-100 treatment reducing P. aeruginosa biofilm growth in the presence of EVs (Figure 3D) because iron-bound transferrin loaded on the extravesicular face of EVs would be accessible to Chelex-100. In this orientation, we anticipated that biotin affinity-purification would isolate entire EVs. To test this hypothesis, we probed biotin-negative and biotin-positive fractions for EV protein markers. We demonstrated that ALIX, Tsg101, Hsp90, and MHC-I were affinity purified with biotinylated transferrin (Figure 4B), which is consistent with transferrin being receptor-bound on the outer surface of EVs. Interestingly, we observed that CD81 and flotillin-1, as well as small amounts of ALIX, Tsg101, Hsp90, and MHC-I, were present in the biotin-negative fraction (Figure 4B), indicating these proteins were not affinity purified with biotinylated transferrin. Thus, our data suggest at least two EV populations exist; one of which is transferrin positive. To investigate whether transferrin-positive EVs were necessary for biofilm biogenesis in the presence of EVs from RSV-infected AECs, we grew P. aeruginosa with EVs that had been depleted of transferrin-positive EVs. We found a significant decrease in P. aeruginosa biofilm growth in the presence of EVs when transferrin-positive EVs were removed (Figure 4C). Although we have shown that transferrin is necessary for P. aeruginosa biofilm growth during RSV co-infection (Hendricks et al., 2016), we observed that growing P. aeruginosa in levels of free transferrin, either apo- (iron-free) or holo-transferrin (iron replete), which corresponds to the levels of iron we observe in EVs (~10 μM iron, ~5 μM transferrin) in abiotic biofilm assays does not significantly increase P. aeruginosa biofilm growth (Figures 4D and S4C). This is consistent with the conclusion that the association of transferrin with EVs is important for transferrin to promote P. aeruginosa biofilm growth during RSV co-infection. Taken together, these data demonstrate that at least two EV populations are released by AECs and the vesicle population containing transcytosed transferrin on the outside of EVs is necessary for P. aeruginosa biofilm biogenesis by RSV-stimulated EVs.

Figure 4. Transcytosed transferrin is loaded on the outside of EVs to enhance P. aeruginosa biofilm growth during RSV infection.

AECs were infected with RSV or mock infected (MEM control) for 48 h. Biotinylated-transferrin was added to the basolateral chamber of RSV or mock-infected AECs at a final concentration of 25 μg/mL. EVs were collected from the apical CM of AECs 24 h later, and biotinylated-transferrin was affinity purified from EV preparations with streptavidin-coated beads. Bead-bound proteins were eluted from the resin (transferrin IP), and supernatant from the streptavidin resin (IP Sup) were separated by SDS-PAGE.

(A) Schematic of experimental design.

(B) Transcytosed transferrin and protein markers of EVs were measured by western blot analysis in transferrin IP (biotin-positive) and IP Sup (biotin-negative) fractions.

(C) P. aeruginosa (GFP) was grown in the presence of EVs in static abiotic biofilm assays after biotin affinity purification to remove transferrin-positive EVs (grid unit = 7.5 μm).

(D) Free, EV-unbound transferrin sources (apo- and holo-transferrin; iron-free and iron-replete, respectively) dissolved in MEM do not promote P. aeruginosa (GFP, green) biofilm growth. Biofilm growth was measured by static abiotic biofilm assays (grid unit = 7.5 μm).

Control, EVs from mock-infected AECs; RSV, EVs from RSV-infected AECs. For all experiments n ≥ 3. Data are presented as means ± SD. *p < 0.05 versus control.

DISCUSSION

EVs are membrane-encapsulated vesicles released by most cell types into the extracellular environment where they facilitate physiological changes in neighboring cells. Although EVs have been reported in the context of viral pathogenesis to modify the local environment and regulate virus-host interactions (Raab-Traub and Dittmer, 2017), very little is understood about the role of EVs in mediating transkingdom interactions. Herein, we demonstrated that EVs released from the respiratory epithelium during respiratory viral infection enhance P. aeruginosa biofilm growth through a mechanism dependent upon increased release of transferrin-containing EVs. The transferrin is oriented on the extravesicular face of EVs, which makes it an accessible iron source for P. aeruginosa biofilm biogenesis. Moreover, we show the EVs associate with P. aeruginosa biofilms and that EVs loaded with iron-bound transferrin are more efficient at stimulating P. aeruginosa biofilm growth than iron-loaded transferrin alone. Our findings propose a role for EVs during viral-bacterial co-infections as a virally induced host nutrient source that promotes P. aeruginosa biofilm growth. Finally, our studies enrich our understanding of molecular mechanisms that govern the clinical observation that respiratory viral infection promotes bacterial infections in patients with chronic lung disease (Collinson et al., 1996; George et al., 2014; Johansen and Hóiby, 1992; Kloepfer et al., 2014).

Although EVs are known to be secreted into the airway lumen (Admyre et al., 2003; Fujita et al., 2015), very little is known about the biological function of EVs during respiratory infections. During virus infection in other organ systems, EVs are known to contain both antiviral and proviral mediators (Bukong et al., 2014; Delorme-Axford et al., 2013; Fu et al., 2017; Li et al., 2013; Ramakrishnaiah et al., 2013). Whether EVs affect the outcome of viral-bacterial infections or how EVs influence bacterial behavior in the airways remains unanswered questions. In our study, EVs isolated from AECs infected with disparate respiratory viruses (i.e., RSV and hRV) promote P. aeruginosa growth. Interestingly, RSV infection increases the apical release of EVs from AECs to promote P. aeruginosa biofilm growth, which is consistent with our observation that the biofilm-stimulatory activity of EVs released by RSV-infected AECs was dose dependent. The increased release of EVs from the respiratory epithelium is in line with other studies that have observed increased EV release in response to stress (i.e., infection) in other epithelial tissues (Fu et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2013; Hurwitz et al., 2017; Ramachandra et al., 2010). Our results demonstrate that EVs mediate transkingdom interactions in the respiratory tract and propose that these observations are likely to be applicable to co-infections at other mucosal sites throughout the body.

EVs commonly exert their biological effects on the local environment by delivering biological molecules to recipient cells. Although the interaction between host-derived EVs and bacteria has not been reported before, we observed that EVs derived from AECs associate with P. aeruginosa biofilms. The mechanism mediating EV association with P. aeruginosa biofilms is not understood. However, it has previously been shown that the RSV G protein promotes association of Haemophilus influenzae and S. pneumoniae with AECs (Avadhanula et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2014). We observed that EVs isolated from RSV-infected AECs contained RSV G protein, among other host membrane proteins. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that an interaction between P. aeruginosa and EV membrane proteins, either host or viral, accounts for the association of EVs with biofilms. Our observations that EVs do not increase bacterial adherence to surfaces but do increase bacterial growth suggest at least one consequence of EV-bacterial interactions is that EVs provide nutrient-rich microenvironments to promote P. aeruginosa growth.

Studies have begun investigating how respiratory viruses alter the nutritional environment and increase nutrient availability in the airways to the benefit of bacteria (Hendricks et al., 2016; Siegel et al., 2014). It has been demonstrated that decreasing free iron levels by addition of exogenous lipocalin 2, a host iron-sequestration protein, reduces bacterial burdens in the respiratory tract during viral-bacterial co-infection (Robinson et al., 2014). Iron is required for many biological processes and is tightly regulated to limit the levels of accessible iron in the host to prevent iron intoxication and limit infections by a process termed nutritional immunity (Cassat and Skaar, 2013; Hood and Skaar, 2012). Previous studies have demonstrated the requirement of iron for P. aeruginosa biofilm growth (Banin et al., 2005; Moreau-Marquis et al., 2008; Patriquin et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2002), but the effect of respiratory viral infections on the nutritional environment in the airways is not well understood. We have previously shown that RSV infection dysregulates this process to promote the apical release of iron and the host iron-binding protein transferrin to stimulate P. aeruginosa biofilm growth (Hendricks et al., 2016), but the mechanism by which iron was released by AECs was unidentified. Here, we have extended these studies and shown that increased EV production by AECs during RSV infection is associated with increased release of transferrin-bound iron during respiratory viral co-infection. Although we cannot entirely eliminate the possibility that transferrin-bound iron is part of a macromolecular protein complex with EV marker proteins associated, we interpret our data to collectively support a model in which the transferrin-bound iron is localized on the extravesicular face of EVs, making it accessible to bacterial pathogens as well as extravesicular molecules, such as iron chelators, which can compete with bacteria for iron to prevent growth and infection.

EVs isolated from hRV-infected AECs also promoted P. aeruginosa biofilm growth but did not have increased iron, leading us to conclude that virus-induced EV simulation of biofilm growth is broadly observed, but different viruses change the cargo composition of EVs distinctively to facilitate transkingdom interactions during polymicrobial infections. During virus infection, EVs are also reported to influence immune cell function (Zhang et al., 2018). It is reasonable to postulate that RSV EVs may induce an altered response in immune cells that encounter EV-bound P. aeruginosa. Immune cells also produce EVs that have a critical role in immunomodulation (Schorey et al., 2015), although they have not been investigated regarding EV-bacterial interactions. Based on the findings detailed in this report that show host-derived AEC EVs associate with P. aeruginosa, it is likely that EVs from other host cells are also capable of associating with and influencing the function of bacteria. How these host-derived EV-bacterial interactions shape immune cell function during respiratory co-infection is a topic of ongoing research in the laboratory.

EVs share many physical and chemical characteristics with enveloped viruses, making separation of EVs from viruses difficult (Nolte-’t Hoen et al., 2016). Because EVs may contain viral components, this further complicates the separation of EVs that carry host proteins, viral proteins, and viral genomic elements from enveloped viruses. Thus, it is likely that diverse subpopulations of EVs are released from cells during virus infection, ranging from infectious virus particles to non-infectious, virus-induced EVs, and host EVs (Nolte-’t Hoen et al., 2016; Raab-Traub and Dittmer, 2017). Moreover, recent studies have demonstrated that defective viral genomes (DVGs) are naturally generated during virus (including influenza virus and RSV) replication and released in immunostimulatory undefined vesicle populations that fall within this spectrum (Sun et al., 2015; Tapia et al., 2013). In our study, we have shown that the EVs isolated during virus infection are not infectious, suggesting that EVs that enhance P. aeruginosa biofilm growth cannot be attributed to infectious virus particles. Additionally, we observed that at least two distinct subpopulations of EVs were released from AECs during RSV infection; one of which was transferrin positive. Although we cannot rule out the presence and contribution of subpopulations of non-infectious virus particles, including DVGs to P. aeruginosa growth, depletion of transferrin-positive EVs significantly reduced P. aeruginosa biofilm growth in the presence of EVs from RSV-infected cells. Thus, we conclude that this subpopulation of EVs was responsible for the biofilm stimulatory effect during RSV co-infection. Our findings collectively suggest that non-infectious, transferrin-positive EVs are responsible for enhancing P. aeruginosa biofilm growth and mediating transkingdom nutrient transfer during viral-bacterial co-infection.

In summary, viral-bacterial interactions result in poor bacterial clearance in patients with chronic lung disease, as well as in acute-infection settings, but the molecular mechanisms underlying these interactions and the role of EVs in these settings remain poorly understood. In this report, we demonstrate that EVs released during respiratory viral infection are used as a nutrient source for secondary bacterial infection. Our data suggest a role of EVs during respiratory viral infections that facilitate transkingdom interactions during polymicrobial infections and provide mechanistic insight into how the host contributes to the development of bacterial biofilm-associated infections during respiratory viral co-infection. Because many infectious diseases are polymicrobial and EVs are released by most cell types throughout the body, our studies likely have implications for host-pathogen interactions in many disease settings.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Jennifer Bomberger (jbomb@pitt.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate any unique code. Additional supplemental data have been deposited on Mendeley: https://doi.org/10.17632/bw7c53gg8g.1.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell culture

Human cells lines, bacterial strains and virus strains used in this study are listed in Key resources table. The immortalized human CF bronchial epithelial cell line CFBE41o- was cultured in minimal essential media (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 5 U/mL penicillin-5 μg/mL streptomycin (P/S) and 0.5 μg/mL Plasmocin prophylactic at 37°C in 5% CO2. CFBE41o- were split and seeded on transwell inserts and grown at air-liquid interface in minimal essential media (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 5 U/mL penicillin-5 μg/mL streptomycin (P/S) and 0.5 μg/mL Plasmocin prophylactic for 7–10 days before use in all experiments. Cells were infected with purified human A2 strain of RSV (MOI = 1), or hRV14 (MOI = 0.1) in the apical compartment. During infections cells were cultured with MEM supplemented with 10% Exosome-depleted FBS (System Biosciences) and 2 mM L-glutamine for 72 hr in the basolateral compartment and MEM supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine (MEM-G) in the apical compartment, unless otherwise noted.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| ALIX | EMD Millipore | Cat. # ABC40; RRID: AB_10806218 |

| Calnexin | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat. # sc-70481; RRID: AB_1119917 |

| CD81 | Thermo Fisher | Cat. # PA5-13582; RRID: AB_2076269 |

| Ferritin | Abcam | Cat. # ab75972; RRID: AB_1310223 |

| Flotillin-1 | BD Biosciences | Cat. # 610820; RRID: AB_398139 |

| GM130 | BD Biosciences | Cat. # 610822; RRID: AB_398141 |

| Hsp90 | Enzo Life Sciences | Cat. # ADI-SPA-830; RRID: AB_10616102 |

| Lactoferrin | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat. # sc-25622; RRID: AB_2139339 |

| MHC-I | LifeSpan Biosciences | Cat. # LS-C107394; RRID: AB_10627058 |

| RSV | Meridian Life Sciences, Inc. | Cat. # B65840G; RRID: AB_152744 |

| Transferrin | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat. # sc-52256; RRID: AB_630356 |

| Tsg101 | GeneTex | Cat. # GTX70255; RRID: AB_373239 |

| Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (HRP-Conjugated) | Bio-Rad | Cat. # 172–1011; RRID: AB_11125936 |

| Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (HRP-Conjugated) | Bio-Rad | Cat. # 172–1019; RRID: AB_11125143 |

| Rat Anti-Goat IgG (HRP-Conjugated) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat. # sc-2020; RRID: AB_631728 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1-GFP [constitutively expresses gfp (pSMC21)] | Lab Stock | N/A |

| Respiratory Syncytial Virus A2 | Lab Stock | N/A |

| Human Rhinovirus 14 | Lab Stock | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| CellTracker Deep Red Dye | Thermo Fisher | Cat. # C34565 |

| Poly(I:C) | InvivoGen | Cat. #tlrl-pic |

| Streptavidin Agarose Resin | Thermo Fisher | Cat. # 20349 |

| Transferrin Biotin-XX-Conjugate | Thermo Fisher | Cat. # T23363 |

| Transferrin Fluorescein Conjugate | Thermo Fisher | Cat. # T2871 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Human IFN-beta DuoSet ELISA | R&D Systems | Cat. # DY814–05 |

| Human IL-29/IL-28B (IFN-lambda 1/3) DuoSet ELISA | R&D Systems | Cat. # DY1598B |

| QuantiChrom Copper Assay Kit | BioAssay Systems | Cat. # DICU-250 |

| QuantiChrom Iron Assay Kit | BioAssay Systems | Cat. # DIFE-250 |

| QuantiChrom Zinc Assay Kit | BioAssay Systems | Cat. # DIZN-250 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Mendeley data – additional supplemental data | This Paper | |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| Human: CFBE41o- | Laboratory of John P. Clancy | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pSMC21 | Kuchma et al., 2005 | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 7 | GraphPad | RRID: SCR_002798; https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| NanoSight NTA 3.2 | Malvern Panalytical | RRID: SCR_014239; https://www.malvernpanalytical.com/en/products/technology/light-scattering/nanoparticle-tracking-analysis |

| Nikon Elements version v4.60 | Nikon Instruments | RRID: SCR_014329; https://www.microscope.healthcare.nikon.com/products/software/nis-elements |

| Other | ||

| 35 mm Glass-Bottom Dish | MatTek Corporation | Cat. # P35G-1.0-14-C |

| 4x Laemmli Sample Buffer | Bio-Rad | Cat. # 1610747 |

| 96-well Microtiter Dishes | Fisher Scientific | Cat. # 07-200-99 |

| 96-well Microtiter Dish Lids | Fisher Scientific | Cat. # 14-245-63A |

| 96-well Plates – Bacterial Growth Curves | Fisher Scientific | Cat. # 08-772-53 |

| Breathe-Easy® Sealing Membrane | Sigma Aldrich | Cat. # Z380059 |

| Corning Costar 75 mm Transwell Inserts | Fisher Scientific | Cat. # 07-200-172 |

| Exosome-Depleted FBS | Fisher Scientific | Cat. # NC0464480 |

| L-arginine | Fisher Scientific | Cat. # BP370-100 |

| L-glutamine | Fisher Scientific | Cat. # MT25005Cl |

| Minimal Essential Media | Thermo Fisher | Cat. # 11095098 |

| Mini-PROTEAN TGX Gels | Bio-Rad | Cat. # 4561084 |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | Sigma Aldrich | Cat. # P0781 |

| PlasmocinTMProphylactic | InvivoGen | Cat. # ant-mpp |

METHOD DETAILS

Extracellular vesicle isolation

EVs were isolated from CM using differential ultracentrifugation, as described previously (Kowal et al., 2016; Théry et al., 2006). Briefly, conditioned media collected from cells was successively centrifuged at 1,400 × g for 3 min, and 10,000 × g for 30 min. Supernatants were filtered through a syringe filter unite, 0.22 μm pore size (Millipore), and then centrifuged for 90 min at 100,000 × g to pellet EVs. Pelleted EVs were resuspended in 1 mL MEM-G (10x concentration compared to conditioned media). All centrifugation steps were performed at 4°C. EV isolation was quantified using nanoparticle tracking analysis [Nanosight LM-10 (Malvern), see below for details].

Static abiotic biofilm imaging

EVs supplemented with 0.4% L-arginine were inoculated with PAO1-GFP (OD600 normalized to 0.5) in glass-bottomed dishes (MatTek Corporation). Briefly, biofilms were grown for 6 hr at 37°C, 5% CO2, and Z stack images of at least 10 random images were taken using a Nikon Ti-inversted microscope to measure the growth of P. aeruginosa biofilms (GFP, green). Nikon Elements Software version 4.60 was used to measure biofilm volume and substratum area. Biofilm biomass was calculated as the ratio of biofilm volume to substratum area.

96-Well microtiter biofilm assay

Biofilm growth on plastic microtiter dishes in the presence of CM or EVs was performed as previously described (Hendricks et al., 2016).

EV fluorescent labeling

AECs were infected with RSV for 48 hr and then stained with CellTracker Deep Red Dye (Thermo Fisher) for 45 min at 37°C. Excess dye was washed away, and EVs were isolated 24 hr later. EV fluorescence was confirmed by measuring fluorescence (Ex630, Em660) in a SpectraMax M2 plate reader. Media alone was used to subtract background fluorescence.

Bacterial growth curves

EVs were inoculated with overnight culture of P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 washed twice in MEM-G. Cultures were added to 96-well plates in quadruplicate and covered with breathable optically clear sealing membrane (Sigma). Plates were placed in SpectraMax M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices) maintained at 37°C, and OD600 was measured every 20 min. Media alone was used to subtract background absorbance.

Growth of pre-attached bacteria

Glass-bottomed dishes (MatTek Corporation) were inoculated with PAO1-GFP diluted in MEM (OD600 normalized to 0.5). Unattached bacteria were gently washed away after 1 h, and biofilms were grown in the presence of EVs for 5 hr at 37°C. Z stack images of at least 10 random images were taken using a Nikon Ti inverted microscope and analyzed by Nikon Elements Software version 4.60. Biofilm biomass was calculated as the ratio of biofilm volume to substratum area.

Divalent metal measurements

Total metals were measured in EVs using QuantiChrom Iron, Copper, and Zinc Assay Kits (BioAssay Systems), respectively.

Transcytosed transferrin measurement on EVs

Transcytosed transferrin abundance on EVs was assessed as described previously with minor modifications (Tan et al., 2011). Briefly, differentiated cells were infected with RSV for 48 hr, as described above, and then the basolateral media was replaced with MEM containing phenol red supplemented with 10% EV-free FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine and 25 μg/mL transferrin biotin-XX-conjugate (Thermo Fisher). MEM-G was added to the apical compartment of cells. EVs were isolated from CM media 24 hr later, and added to Streptavidin Agarose Resin (Thermo Fisher) for 2 hr at 4°C with continuous rotation. Resin was washed twice in MEM, once in high salt solution (200 mM NaCl, 400 mM NaOAc, pH 7.4) and once more in MEM. Affinity-purified protein were eluted from resin with Laemmli Sample Buffer supplemented with dithiothreitol (DTT) and analyzed by western blot for transferrin or EV markers. Supernatants were analyzed by western blot for transferrin or EVs markers.

Depletion of transferrin containing EVs for static abiotic biofilm assays

Differentiated AECs were infected, as described above, and then the basolateral media was replaced with MEM containing phenol red supplemented with 10% EV-free FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine and 25 μg/mL transferrin biotin-XX-conjugate (Thermo Fisher) 48 hr post-infection. MEM-G was added to the apical compartment of AECs. EVs were isolated from CM media 24 hr later. EVs were added to Streptavidin Agarose Resin (Thermo Fisher) for 2 hr at 4°C with continuous rotation. Following rotation, Streptavidin Agarose Resin (including transferrin biotin-XX-conjugate containing EVs bound to resin) was pelleted from EVs at 10,000 × g for 2 min. Supernatant containing EVs (not containing transferrin biotin-XX-conjugate) was collected and used in static abiotic biofilm assays, as described above.

Western blot

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on Tris gels (Bio-Rad) and were transferred onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad), as previously described (Bomberger et al., 2011). The following antibodies were used for protein detection: anti-ALIX (EMD Milllipore), anti-calnexin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-CD81 (Thermo Fisher), anti-Flotillin-1 (BD Biosciences), anti-ferritin (Abcam), anti-GM130 (BD Biosciences), anti-Hsp90 (Enzo Life Sciences), anti-lactoferrin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-MHC-I (LifeSpan Biosciences), anti-RSV (Meridian Life Science, Inc.), anti-transferrin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Tsg101 (GeneTex). Secondary antibodies were goat anti-mouse, goat anti-rabbit, and rat anti-goat conjugated to HRP (Bio-Rad).

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA)

EV size distribution and concentration were quantified by Nanosight LM-10 (Malvern) using a blue 405nm laser, as described previously (Ouyang et al., 2016). Briefly, EVs were diluted to an appropriate level (100- to 5,000-fold dilution) with 0.1 μM filtered PBS (Sigma). The diluted particles were continuously injected by syringe pump into the Nanosight LM-10 view field. Particles were individually recorded and tracked for 1 min, and all frames captured were analyzed by NTA particle analysis software.

Poly(I:C) treatment

High molecular weight polyinosinic-polycitidylic acid (poly (I:C)) was floated on AECs and incubated for 72 hr, as previously described with minor modifications (Dauletbaev et al., 2015; Ioannidis et al., 2013). Differentiated AECs were treated apically with 100ug/mL poly (I:C) (Invivogen) and basolateral media was replaced with MEM supplemented with 10% exosome-free FBS. After a 2-hour incubation, apical media was removed. MEM-G was added to the apical compartment of cells for the final 24 hr to collect EVs.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Experiments were performed at least three times as indicated in the figure legends. Data are presented as mean ± SD. GraphPad Prism version 7.0 (GraphPad) was used for statistical analysis. Means were compared using Student’s t test when two datasets were compared, and for multiple comparisons, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons. p < 0.5 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) associate with Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms

EVs secreted from virus-infected respiratory epithelia promote P. aeruginosa biofilm

RSV infection increases transcytosed transferrin and iron on EVs to promote biofilm

EVs are a nutrient source that mediate host-pathogen interactions in the lung

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Seema Lakdawala, Carolyn Coyne, and Megan Kiedrowski (University of Pittsburgh) for helpful discussion and constructive comments in the writing of this manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants T32AI060525 (to M.R.H. and S.L.; PI: JoAnne L. Flynn), T32AI049820 (to J.A.M.; PI: Neal A. DeLuca), and RO1HL123771 (to J.M.B.) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation grants MELVIN15F0 (to J.A.M.) and BOMBER14G0 (to J.M.B.).

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108672.

REFERENCES

- Admyre C, Grunewald J, Thyberg J, Gripenbäck S, Tornling G, Eklund A, Scheynius A, and Gabrielsson S (2003). Exosomes with major histocompatibility complex class II and co-stimulatory molecules are present in human BAL fluid. Eur. Respir. J. 22, 578–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avadhanula V, Wang Y, Portner A, and Adderson E (2007). Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae bind respiratory syncytial virus glycoprotein. J. Med. Microbiol. 56, 1133–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banin E, Vasil ML, and Greenberg EP (2005). Iron and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11076–11081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnsholt T, Jensen PO, Fiandaca MJ, Pedersen J, Hansen CR, Andersen CB, Pressler T, Givskov M, and Høiby N (2009). Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in the respiratory tract of cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 44, 547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomberger JM, Ye S, Maceachran DP, Koeppen K, Barnaby RL, O’Toole GA, and Stanton BA (2011). A Pseudomonas aeruginosa toxin that hijacks the host ubiquitin proteolytic system. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1001325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukong TN, Momen-Heravi F, Kodys K, Bala S, and Szabo G (2014). Exosomes from hepatitis C infected patients transmit HCV infection and contain replication competent viral RNA in complex with Ago2-miR122-HSP90. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassat JE, and Skaar EP (2013). Iron in infection and immunity. Cell Host Microbe 13, 509–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahar HS, Corsello T, Kudlicki AS, Komaravelli N, and Casola A (2018). Respiratory syncytial virus infection changes cargo composition of exosome released from airway epithelial cells. Sci. Rep. 8, 387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinson J, Nicholson KG, Cancio E, Ashman J, Ireland DC, Hammersley V, Kent J, and O’Callaghan C (1996). Effects of upper respiratory tract infections in patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 51, 1115–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauletbaev N, Cammisano M, Herscovitch K, and Lands LC (2015). Stimulation of the RIG-I/MAVS pathway by polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid upregulates IFN-β in airway epithelial cells with minimal costimulation of IL-8. J. Immunol. 195, 2829–2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorme-Axford E, Donker RB, Mouillet JF, Chu T, Bayer A, Ouyang Y, Wang T, Stolz DB, Sarkar SN, Morelli AE, et al. (2013). Human placental trophoblasts confer viral resistance to recipient cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 12048–12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Zhang L, Zhang F, Tang T, Zhou Q, Feng C, Jin Y, and Wu Z (2017). Exosome-mediated miR-146a transfer suppresses type I interferon response and facilitates EV71 infection. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Kosaka N, Araya J, Kuwano K, and Ochiya T (2015). Extracellular vesicles in lung microenvironment and pathogenesis. Trends Mol. Med. 21, 533–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SN, Garcha DS, Mackay AJ, Patel AR, Singh R, Sapsford RJ, Donaldson GC, and Wedzicha JA (2014). Human rhinovirus infection during naturally occurring COPD exacerbations. Eur. Respir. J. 44, 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hament JM, Aerts PC, Fleer A, van Dijk H, Harmsen T, Kimpen JL, and Wolfs TF (2005). Direct binding of respiratory syncytial virus to pneumococci: a phenomenon that enhances both pneumococcal adherence to human epithelial cells and pneumococcal invasiveness in a murine model. Pediatr. Res. 58, 1198–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks MR, Lashua LP, Fischer DK, Flitter BA, Eichinger KM, Durbin JE, Sarkar SN, Coyne CB, Empey KM, and Bomberger JM (2016). Respiratory syncytial virus infection enhances Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm growth through dysregulation of nutritional immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1642–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood MI, and Skaar EP (2012). Nutritional immunity: transition metals at the pathogen-host interface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 525–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Gong AY, Roth AL, Huang BQ, Ward HD, Zhu G, Larusso NF, Hanson ND, and Chen XM (2013). Release of luminal exosomes contributes to TLR4-mediated epithelial antimicrobial defense. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz SN, Nkosi D, Conlon MM, York SB, Liu X, Tremblay DC, and Meckes DG Jr. (2017). CD63 regulates Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 exosomal packaging, enhancement of vesicle production, and noncanonical NF-κB signaling. J. Virol. 91, e02251–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis I, Ye F, McNally B, Willette M, and Flaño E (2013). Toll-like receptor expression and induction of type I and type III interferons in primary airway epithelial cells. J. Virol. 87, 3261–3270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen HK, and Høiby N (1992). Seasonal onset of initial colonisation and chronic infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with cystic fibrosis in Denmark. Thorax 47, 109–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesimer M, Scull M, Brighton B, DeMaria G, Burns K, O’Neal W, Pickles RJ, and Sheehan JK (2009). Characterization of exosome-like vesicles released from human tracheobronchial ciliated epithelium: a possible role in innate defense. FASEB J. 23, 1858–1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloepfer KM, Lee WM, Pappas TE, Kang TJ, Vrtis RF, Evans MD, Gangnon RE, Bochkov YA, Jackson DJ, Lemanske RF Jr., et al. (2014). Detection of pathogenic bacteria during rhinovirus infection is associated with increased respiratory symptoms and asthma exacerbations. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 133, 1301–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal J, Arras G, Colombo M, Jouve M, Morath JP, Primdal-Bengtson B, Dingli F, Loew D, Tkach M, and Théry C (2016). Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, E968–E977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchma SL, Connolly JP, and O’Toole GA (2005). A three-component regulatory system regulates biofilm maturation and type III secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 187, 1441–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Liu K, Liu Y, Xu Y, Zhang F, Yang H, Liu J, Pan T, Chen J, Wu M, et al. (2013). Exosomes mediate the cell-to-cell transmission of IFN-α-induced antiviral activity. Nat. Immunol. 14, 793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Ren A, Wang X, Fan X, Zhao Y, Gao GF, Cleary P, and Wang B (2015). Influenza viral neuraminidase primes bacterial coinfection through TGF-β-mediated expression of host cell receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 238–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Cicero A, Stahl PD, and Raposo G (2015). Extracellular vesicles shuffling intercellular messages: for good or for bad. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 35, 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon HG, Kim SH, Gao J, Quan T, Qin Z, Osorio JC, Rosas IO, Wu M, Tesfaigzi Y, and Jin Y (2014). CCN1 secretion and cleavage regulate the lung epithelial cell functions after cigarette smoke. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 307, L326–L337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau-Marquis S, Bomberger JM, Anderson GG, Swiatecka-Urban A, Ye S, O’Toole GA, and Stanton BA (2008). The DeltaF508-CFTR mutation results in increased biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa by increasing iron availability. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 295, L25–L37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte-’t Hoen E, Cremer T, Gallo RC, and Margolis LB (2016). Extracellular vesicles and viruses: are they close relatives? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 9155–9161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novotny LA, and Bakaletz LO (2016). Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 serves as a primary cognate receptor for the type IV pilus of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Cell. Microbiol. 18, 1043–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang Y, Bayer A, Chu T, Tyurin VA, Kagan VE, Morelli AE, Coyne CB, and Sadovsky Y (2016). Isolation of human trophoblastic extracellular vesicles and characterization of their cargo and antiviral activity. Placenta 47, 86–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patriquin GM, Banin E, Gilmour C, Tuchman R, Greenberg EP, and Poole K (2008). Influence of quorum sensing and iron on twitching motility and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 190, 662–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raab-Traub N, and Dittmer DP (2017). Viral effects on the content and function of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 559–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandra L, Qu Y, Wang Y, Lewis CJ, Cobb BA, Takatsu K, Boom WH, Dubyak GR, and Harding CV (2010). Mycobacterium tuberculosis synergizes with ATP to induce release of microvesicles and exosomes containing major histocompatibility complex class II molecules capable of antigen presentation. Infect. Immun. 78, 5116–5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnaiah V, Thumann C, Fofana I, Habersetzer F, Pan Q, de Ruiter PE, Willemsen R, Demmers JA, Stalin Raj V, Jenster G, et al. (2013). Exosome-mediated transmission of hepatitis C virus between human hepatoma Huh7.5 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13109–13113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson KM, McHugh KJ, Mandalapu S, Clay ME, Lee B, Scheller EV, Enelow RI, Chan YR, Kolls JK, and Alcorn JF (2014). Influenza A virus exacerbates Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia in mice by attenuating antimicrobial peptide production. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 865–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rynda-Apple A, Robinson KM, and Alcorn JF (2015). Influenza and bacterial superinfection: illuminating the immunologic mechanisms of disease. Infect. Immun. 83, 3764–3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorey JS, Cheng Y, Singh PP, and Smith VL (2015). Exosomes and other extracellular vesicles in host-pathogen interactions. EMBO Rep 16, 24–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel SJ, Roche AM, and Weiser JN (2014). Influenza promotes pneumococcal growth during coinfection by providing host sialylated substrates as a nutrient source. Cell Host Microbe 16, 55–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PK, Schaefer AL, Parsek MR, Moninger TO, Welsh MJ, and Greenberg EP (2000). Quorum-sensing signals indicate that cystic fibrosis lungs are infected with bacterial biofilms. Nature 407, 762–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh PK, Parsek MR, Greenberg EP, and Welsh MJ (2002). A component of innate immunity prevents bacterial biofilm development. Nature 417, 552–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CM, Sandrini S, Datta S, Freestone P, Shafeeq S, Radhakrishnan P, Williams G, Glenn SM, Kuipers OP, Hirst RA, et al. (2014). Respiratory syncytial virus increases the virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae by binding to penicillin binding protein 1a: a new paradigm in respiratory infection. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 190, 196–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Jain D, Koziol-White CJ, Genoyer E, Gilbert M, Tapia K, Panettieri RA Jr., Hodinka RL, and López CB (2015). Immunostimulatory defective viral genomes from respiratory syncytial virus promote a strong innate antiviral response during infection in mice and humans. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szul T, Bratcher PE, Fraser KB, Kong M, Tirouvanziam R, Ingersoll S, Sztul E, Rangarajan S, Blalock JE, Xu X, and Gaggar A (2016). Toll-like receptor 4 engagement mediates prolyl endopeptidase release from airway epithelia via exosomes. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 54, 359–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S, Noto JM, Romero-Gallo J, Peek RM Jr., and Amieva MR (2011). Helicobacter pylori perturbs iron trafficking in the epithelium to grow on the cell surface. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia K, Kim WK, Sun Y, Mercado-López X, Dunay E, Wise M, Adu M, and López CB (2013). Defective viral genomes arising in vivo provide critical danger signals for the triggering of lung antiviral immunity. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théry C, Amigorena S, Raposo G, and Clayton A (2006). Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. Chapter 3, Unit 3.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torregrosa Paredes P, Esser J, Admyre C, Nord M, Rahman QK, Lukic A, Rådmark O, Grönneberg R, Grunewald J, Eklund A, et al. (2012). Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid exosomes contribute to cytokine and leukotriene production in allergic asthma. Allergy 67, 911–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ewijk BE, van der Zalm MM, Wolfs TF, Fleer A, Kimpen JL, Wilbrink B, and van der Ent CK (2008). Prevalence and impact of respiratory viral infections in young children with cystic fibrosis: prospective cohort study. Pediatrics 122, 1171–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Jiang X, Bao J, Wang Y, Liu H, and Tang L (2018). Exosomes in pathogen infections: a bridge to deliver molecules and link functions. Front. Immunol. 9, 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate any unique code. Additional supplemental data have been deposited on Mendeley: https://doi.org/10.17632/bw7c53gg8g.1.