Abstract

A position statement developed by the Canadian Psychiatric Association’s (CPA) Research Committee and approved by the CPA’s Board of Directors on May 13, 2020.

The Canadian Psychiatric Association (CPA; www.cpa-apc.org) is the professional association for over 4,700 psychiatrists and 900 psychiatry residents in Canada. In addressing its mission, the CPA uses evidence-based methods to not only educate and inform the public and its own membership but also to develop mental health programs, services and policies.

In response to the federal government legalizing and regulating access to cannabis in 2017, the CPA published a position statement with respect to cannabis use and adverse health consequences in youth and young adults1 based on the accumulating evidence of negative consequences of early sustained use (e.g., National Academies of Sciences and Medicine, 2017).2 However, psychiatrists and other mental health professionals are also being asked about the potential therapeutic uses of cannabis and cannabinoid products for mental illnesses; information is widely distributed on cannabis use being associated with mental wellness and suggesting cannabis use as a treatment for a variety of mental health concerns. As the CPA is evidence based, it is prudent to examine the existing research in this area to inform our membership needs and thus the public.

In Canada, before a new medication can be approved (or, an existing medication can be prescribed to treat a previously unrecognized condition), it must pass through Health Canada’s regulatory approval process. As part of this process, clinical trial data must show a positive therapeutic effect on symptoms and that this effect is not associated with significant risks (e.g., potential side effects). For therapeutic indications and clinical decision making, Level 1 evidence is usually required. Level 1 evidence includes systematic reviews of randomized control trials (RCTs) or high-quality individual RCTs (see Centre for Evidence-based Medicine for details, http://www.cebm.net.)

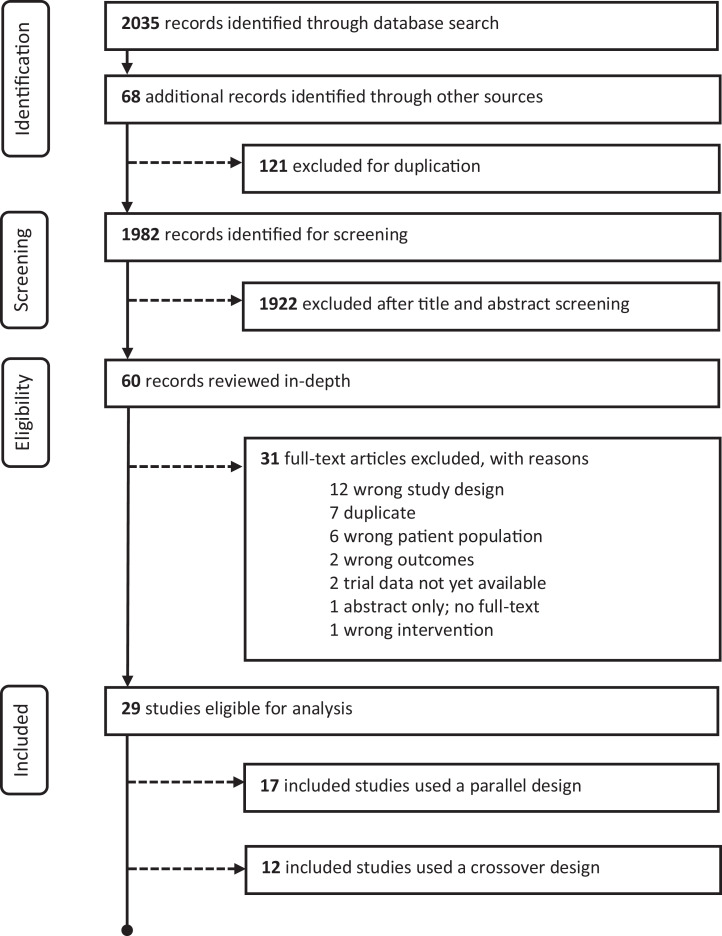

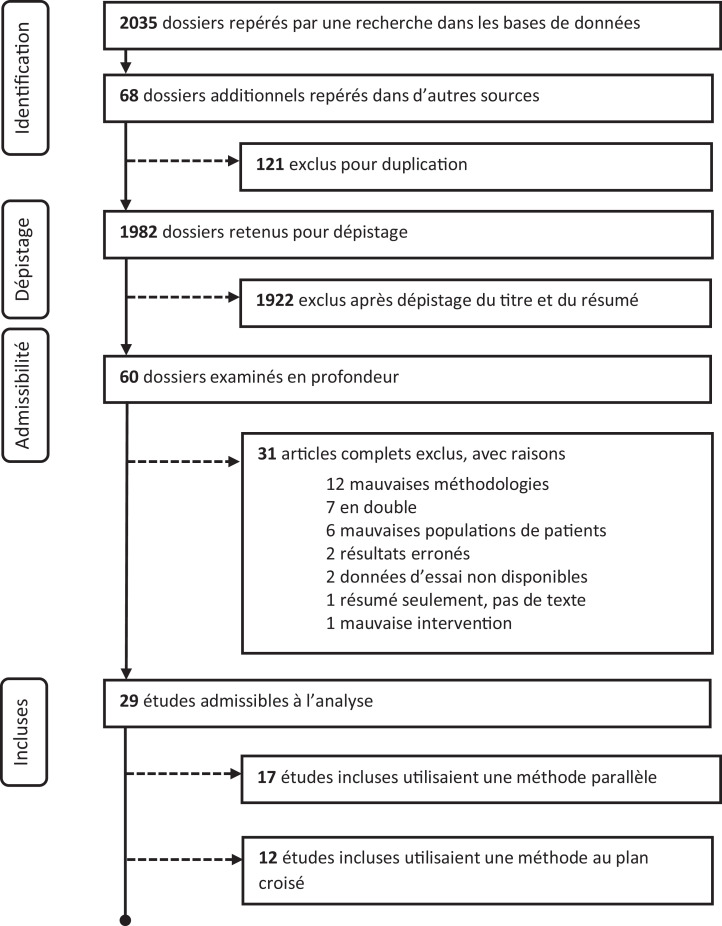

The CPA has systematically reviewed the existing literature on RCTs examining potential beneficial uses of cannabis and cannabinoid products to treat mental illness. This review incorporated studies in adults only (greater than 18 years old). Of the 1,982 papers identified, 29 RCTs were available to review (see Figure 1 for systematic review flow diagram). Methodological quality for each study was assessed using Cochrane Collaboration guidelines.3 The 29 publications were in the following clinical areas: anxiety disorders (three RCTs),4–6 post-traumatic stress disorder (one RCT),7 psychotic disorders (six RCTs),8–13 anorexia nervosa (two RCTs),14,15 cannabis dependence management (nine RCTs),16–24 nicotine/opioid dependence (five RCTs),25-29 attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (one RCT)30 and Tourette’s disorder (two RCTs).31,32

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

The clinical trials identified followed accepted designs (parallel or crossover design methodology); however, sample sizes were relatively small in most of the RCTs, which weakens the conclusions, and they evaluated a variety of naturally derived and synthetic tetrahydrocannabinol (THC; e.g., nabilone, dronabinol, nabiximols) and cannabidiol products at varying doses across studies, making comparisons difficult. Results were often not specific to the primary psychiatric symptoms that the trial was designed to address. Of note, no studies used combustible dried cannabis or cannabis edibles. Results of some studies showed atypical dose–response effects. Also, there were no RCTs investigating the potential benefits of cannabinoid products in major depressive disorder (i.e., clinical level depression) or bipolar disorders. While different inclusion and exclusion criteria were used for manuscript selection, the results discussed here are comparable to another recent systematic review and meta-analysis on this topic.33

With respect to the use of cannabis and cannabinoid products in mental illness, based on the current evidence, the CPA:

Acknowledges there are no current Health Canada–approved indications for use of cannabis or cannabinoid products for the treatment of mental illness.

Acknowledges there is some limited evidence for use of cannabinoid products (excluding combustible dried cannabis and cannabis edibles) for the treatment of mental illness, but the evidence base is currently of low-quality and below that required to meet Level 1 evidence.

Strongly discourages cannabis and cannabinoid product use by anyone experiencing mental illness. Use of cannabis or a cannabinoid product should never delay (or replace) more evidence-based forms of treatment. We encourage patients to discuss potential harms of use with their treating physician.

Recommends that mental health care professionals should approach counselling around cannabinoid-based treatments with appropriate caution given the known side effects and lack of positive RCTs.

Recommends that any discussion of the potential therapeutic benefit of cannabinoid products be balanced with the risk for adverse outcomes (e.g., worsening of the underlying illness, addiction, cognitive impairment) and should be within the context of the methodology of the current RCTs, which includes carefully chosen cannabinoid products, dosing, side effect monitoring and regimented drug administration.

To better assess whether cannabinoid-based products have any therapeutic value, larger neuroscience-based, hypothesis-driven RCTs are needed and should include varying lower risk products (e.g., low THC concentration), dose ranges and routes of administration. Narrowing the knowledge gap with high-quality RCTs should be a priority for all stakeholders.

Recommends that agencies (e.g., provincial/federal governments, nonprofit organizations) address the apparent disconnect between popular public opinion and the lack of available high-level research evidence supporting the therapeutic uses of cannabinoid products in mental illness.

Footnotes

Searched databases: Academic Search Premier, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Ovid MEDLINE, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science™.

Additional records searched: Google Scholar (first 25 pages); ClinicalTrials.gov; World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry, and Health Canada’s Clinical Trials Database.

References

- 1. Tibbo P, Crocker CE, Lam RW, Meyer J, Sareen J, Aitchison KJ. Implications of cannabis legalization on youth and young adults. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(1):65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Academies of Sciences and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Higgins JPT, Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Hróbjartsson A, Boutron I, Reeves B, Eldridge S. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. In: Chandler J, McKenzie J, Boutron I, Welch V, editors. Cochrane methods. Cochrane database of systematic reviews; 2016. 10.1002/14651858.CD201601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Trauma- and Stress-related Disorders

Anxiety

- 4. Bergamaschi MM, Queiroz RHC, Chagas MHN, et al. Cannabidiol reduces the anxiety induced by simulated public speaking in treatment-nave social phobia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(6):1219–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crippa JAS, Derenusson GN, Ferrari TB, et al. Neural basis of anxiolytic effects of cannabidiol (CBD) in generalized social anxiety disorder: a preliminary report. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(1):121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fabre LF, McLendon D. The efficacy and safety of nabilone (a synthetic cannabinoid) in the treatment of anxiety. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21:377S–382S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

- 7. Jetly R, Heber A, Fraser G, et al. The efficacy of nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, in the treatment of PTSD-associated nightmares: a preliminary randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over design study. Psycho Neuroendocrinology. 2015;51(2):585–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schizophrenia

- 8. Boggs DL, Kelly DL, McMahon RP, et al. Rimonabant for neurocognition in schizophrenia: a 16-week double blind randomized placebo controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2012;134(2-3):207–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boggs DL, Surti T, Gupta A, et al. The effects of cannabidiol (CBD) on cognition and symptoms in outpatients with chronic schizophrenia a randomized placebo controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(7):1923–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. D’Souza DC, Abi-Saab WM, Madonick S, et al. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol effects in schizophrenia: Implications for cognition, psychosis, and addiction. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(6):594–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leweke FM, Piomelli D, Pahlisch F, et al. Cannabidiol enhances anandamide signaling and alleviates psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. Trans Psychiatry. 2012;2(3):e94–e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McGuire P, Robson P, Cubala WJ, et al. Cannabidiol (CBD) as an adjunctive therapy in schizophrenia: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(3):225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meltzer HY, Arvanitis L, Bauer D, et al. Placebo-controlled evaluation of four novel compounds for the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(6):975–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eating Disorders

Anorexia-Nervosa

- 14. Andries A, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, et al. Dronabinol in severe, enduring anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(1):18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Andries A, Gram B, Støving RK. Effect of dronabinol therapy on physical activity in anorexia nervosa: a randomised, controlled trial. Eat Weight Disord. 2015;20(1):13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Substance-related Disorders

Cannabis Dependence

- 16. Lintzeris N, Bhardwaj A, Mills L, et al. Nabiximols for the treatment of cannabis dependence. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(9):1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hill KP, Palastro MD, Gruber SA, et al. Nabilone pharmacotherapy for cannabis dependence: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Am J Addict. 2017;26(8):795–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lundahl LH, Greenwald MK. Effect of oral THC pretreatment on marijuana cue-induced responses in cannabis dependent volunteers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;14:9187–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trigo JM, Soliman A, Quilty LC, et al. Nabiximols combined with motivational enhancement/cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of cannabis dependence: a pilot randomized clinical trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schlienz NJ, Lee DC, Stitzer ML, et al. The effect of high-dose dronabinol (oral THC) maintenance on cannabis self-administration. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;18:7254–7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Trigo JM, Lagzdins D, Rehm J, et al. Effects of fixed or self-titrated dosages of Sativex on cannabis withdrawal and cravings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161(2016):298–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Levin FR, Mariani JJ, Brooks DJ, et al. Dronabinol for the treatment of cannabis dependence: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116(1-3):142–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vandrey R, Stitzer ML, Mintzer MZ, et al. The dose effects of short-term dronabinol (oral THC) maintenance in daily cannabis users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128(1–2):64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Allsop DJ, Copeland J, Lintzeris N, et al. Nabiximols as an agonist replacement therapy during cannabis withdrawal. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(3):281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Opioid Dependence

- 25. Hurd YL, Spriggs S, Alishayev J, et al. Cannabidiol for the reduction of cue-induced craving and anxiety in drug-abstinent individuals with heroin use disorder: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(11):911–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bisaga A, Sullivan MA, Glass A, et al. The effects of dronabinol during detoxification and the initiation of treatment with extended release naltrexone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;15:438–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lofwall MR, Babalonis S, Nuzzo PA, et al. Opioid withdrawal suppression efficacy of oral dronabinol in opioid dependent humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;16:4143–4150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tobacco Dependence

- 28. Morgan CJA, Das RK, Joye A, et al. Cannabidiol reduces cigarette consumption in tobacco smokers: preliminary findings. Addict Behav. 2013;38(9):2433–2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Robinson JD, Cinciripini PM, Karam-Hage M, et al. Pooled analysis of three randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trials with rimonabant for smoking cessation. Addict Biol. 2018;23(1):291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Attention-deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- 30. Cooper RE, Williams E, Seegobin S, et al. Cannabinoids in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomised-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27(8):795–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tourette’s Disorder

- 31. Müller-Vahl K, Schneider U, Koblenz A, et al. Treatment of Tourette’s syndrome with δ 9 -tetrahydrocannabinol (THC): a randomized crossover trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2002;35(02):57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Muller-Vahl KR, Schneider U, Prevedel H, et al. Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is effective in the treatment of tics in Tourette syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(4):459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- 33. Black N, Stockings E, Campbell G, Tran LT, Zagic D, Hall WD, Farrell M, Degenhart L. Cannabinoids for the treatment of mental disorders and symptoms of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:9:95–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]