Abstract

Objective:

A variety of patient characteristics drive the use of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in depression. However, the extent to which each characteristic influences the receipt of ECT, and whether they are appropriate, is unknown. The aim of this study is to identify patient-level characteristics associated with receiving inpatient ECT for depression.

Method:

We identified all psychiatric inpatients with a major depressive episode admitted to hospital ≥3 days in Ontario, Canada (2009 to 2017). The association between patient-level characteristics at admission and receipt of inpatient ECT was determined using logistic regression, where a generalized estimating equations approach accounted for repeat admissions.

Results:

The cohort included 53,174 inpatients experiencing 75,429 admissions, with 6,899 admissions involving ECT (9.2%). Among demographic factors, age was most associated with ECT—younger adults had reduced (OR = 0.30, 95%CI, 0.24 to 0.37; 18 to 25 years) while older adults had increased (OR = 3.08, 95%CI, 2.41 to 3.93; 85+ years) odds compared to middle-aged adults (46 to 55 years). The likelihood of ECT was greater for individuals who were married/partnered, had postsecondary education, and resided in the highest neighborhood income quintile. Among clinical factors, illness polarity was most associated with receiving ECT—bipolar depression had reduced odds of receiving ECT (OR = 0.62, 95%CI, 0.57 to 0.69) The likelihood of receiving ECT was greater in psychotic depression, more depressive symptoms, and incapable to consent to treatment and was reduced with comorbid substance use disorders and several medical comorbidities.

Conclusions:

Nearly 1 in 10 admissions for depression in Ontario, Canada, involve ECT. Many clinical factors associated with receiving inpatient ECT were concordant with clinical guidelines; however, nonclinical factors associated with its use warrant investigation of their impact on equitable access to ECT.

Keywords: electroconvulsive therapy, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, observational study, regression analysis

Abstract

Objectif:

Diverses caractéristiques des patients régissent l’utilisation de la thérapie électroconvulsive (TEC) dans la dépression. Cependant, on ne connaît pas la mesure dans laquelle ces caractéristiques influencent la réception de la TEC, ni si elles sont appropriées. La présente étude vise à identifier les caractéristiques du patient qui sont associées à la réception de la TEC pour la dépression des patients hospitalisés.

Méthode:

Nous avons identifié tous les patients psychiatriques hospitalisés souffrant d’un épisode dépressif majeur et séjournant ≥3 jours à l’hôpital en Ontario, Canada (2009-2017). L’association entre les caractéristiques du patient au moment de l’hospitalisation et la réception de la TEC pour patients hospitalisés était déterminée à l’aide de la régression logistique, dans laquelle une approche généralisée d’équations d’estimation tenait compte des hospitalisations répétées.

Résultats:

La cohorte comprenait 53 174 patients hospitalisés comptant 75 429 hospitalisations, dont 6 899 comportaient une TEC (9,2 %). Parmi les facteurs démographiques, l’âge était le plus associé à la TEC – les jeunes adultes avaient des probabilités réduites (RC 0,30; IC à 95 % 0,24 à 0,37 18-25 ans) alors que les adultes plus âgés avaient des probabilités accrues (3,06; 2,40 à 3,90 85+ans) comparés aux adultes d’âge moyen (46-55 ans). La probabilité de la TEC était plus grande pour les personnes qui étaient mariées ou en couple, qui avaient une instruction post-secondaire, et qui résidaient dans le quintile de revenu de quartier le plus élevé. Parmi les facteurs cliniques, la polarité de la maladie était la plus associée à la réception de la TEC – la dépression bipolaire avait des probabilités réduites de recevoir la TEC (0,63; 0,57 à 0,69). La probabilité de recevoir la TEC était plus grande dans la dépression psychotique, les symptômes plus dépressifs, et l’incapacité de consentir au traitement. Elle était réduite en présence de troubles comorbides d’utilisation de substances et de plusieurs comorbidités médicales.

Conclusions:

Près d’une hospitalisation sur 10 pour dépression en Ontario, Canada implique une TEC. Nombre de facteurs cliniques associés à la réception d’une TEC pour patients hospitalisés concordaient avec les lignes de conduite cliniques; toutefois, les facteurs non cliniques associés à l’utilisation de la TEC justifient de rechercher l’effet de ces facteurs sur l’accès équitable à la TEC.

Introduction

Depression is a leading cause of illness and disability burden worldwide.1 A particularly challenging clinical scenario for affected individuals is treatment-resistant depression (TRD), which is defined based on nonresponsiveness to initial pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy,2 affecting more than 50% of individuals with depression.3 Of the individuals with TRD,3 only 13.0% and 13.7% achieve remission after 3 and 4 trials of pharmacotherapy.3 Among treatment options for these individuals, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) offers great benefits in that it achieves remission in 60% of TRD patients,4 with some studies finding remission rates as high as 95% for individuals with depression with psychotic features.5 Furthermore, ECT is extremely effective at rapidly reducing suicidality.6 Consequently, practice guidelines recommend ECT as a first-line treatment for TRD and in situations where rapid treatment is critical—such as acute suicidality or psychotic depression.7

Despite its efficacy in TRD, ECT remains underutilized; indeed, in some regions, its use is declining,8,9 suggesting clinical practice guidelines do not always reflect real-world application of important treatments. Furthermore, previous work has pointed out disparities in access to ECT treatment, as evidenced by nonclinical factors such as being unmarried, less educated, black race, and lack of proximity to ECT treatment facilities being associated with lower probability of receiving treatment.10,11 Understanding the real-world implementation of ECT, and in particular characteristics of patients who do and do not receive it, may help identify populations to specifically target and improve access to ECT. Previous studies in this area have had shortcomings that limited their ability to achieve this goal. For example, many ECT studies have been too small to identify specific characteristics associated with real-world implementation.12 Other studies have used large health care data sets but were limited to specific populations such as the U.S. Veterans Affairs health system10,12 or to patients with private insurance.13 Two prior studies used population-level data in Ontario, Canada,14,15 to characterize the use of ECT across the province but did not consider detailed clinical characteristics such as depression severity, cognitive functioning, medical/psychiatric comorbidities, and medications—all key characteristics influencing the decision to offer ECT.7

The goal of this study was to identify patient-level characteristics associated with receipt of ECT in a large, clinically representative cohort of patients with depression who might be candidates for ECT.

Methods

Setting and Data Sources

We conducted a population-based cross-sectional study in Ontario, Canada, using linked administrative health care databases available through ICES, an independent nonprofit research organization evaluating health care services across Ontario. These data sets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. Data sources used for this study included (1) Registered Persons Database (RPDB) that contains date of birth, sex, and postal code for all Ontario Residents; (2) Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database (CIHI-DAD) that contains clinical information about medical hospital admissions and discharges coded using standard diagnoses (ICD-10-CA); (3) CIHI Ontario Mental Health Reporting System (OMHRS) that contains mental health hospital data from all facilities with designated adult inpatient mental health beds; (4) CIHI National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS) that contains clinical information about emergency department visits coded using standard diagnoses (ICD-10-CA); (5) Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) Claims Database that contains information related to physician services submitted for reimbursement; and (6) Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) that includes details on all publicly funded prescription medications dispensed through retail pharmacies to eligible individuals including those >65, residents of long-term care, or recipients of home-care services, social assistance (Ontario Works or Ontario Disability Support Program), or medication payment assistance (Trillium Drug Program). The use of data in this project was authorized under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which does not require review by a Research Ethics Board.

Study Population

Using the OMHRS data set, we identified all adult (≥18 years) residents of Ontario admitted for at least 3 days to a designated psychiatric inpatient unit at an Ontario hospital between April 1, 2007, to March 31, 2017. We excluded individuals with short-stay admissions (<3 days) because these patients receive abbreviated assessments that would not contain detailed clinical information required to assess their suitability for ECT. Any patient with a discharge diagnosis of a major depressive episode—including both unipolar major depressive disorder and bipolar affective disorder—was included in this study (diagnostic codes are in Supplemental Table S1). Patients with non-affective psychotic disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder) were included, provided they had a discharge diagnosis of depression.

Receipt of ECT Treatment

Treatment with ECT during each eligible admission was determined using OHIP physician billing codes for inpatient ECT procedures (G478). OHIP procedure codes are considered to be reliable and valid sources of information with respect to physician billing for procedures and visits.16 Receipt of ECT was treated as a binary variable throughout the analyses.

Covariates

We included covariates assessed at each admission to the psychiatric inpatient unit including sociodemographic, clinical, psychiatric/functional symptoms, and service utilization characteristics. The RPDB data set was used to ascertain age, neighborhood income quintile, and rural residence status. From the OMHRS data set, we included marital status, education level, employment status, reason for admission, type of admission (voluntary vs. involuntary), substance use, psychiatric comorbidities, capacity to consent to psychiatric treatment, and body mass index. The OMHRS data set also includes standardized psychiatric and functional scales adapted from the Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum Dataset.17 Scales included for the current study were the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Hierarchy Scale (assesses daily functioning of ADLs), Aggressive Behavior Scale (measure of aggressive behavior), Social Withdrawal Scale (assesses occurrence of anhedonia, lack of motivation and reduction in socialization), Cognitive Performance Scale (a clinician rated objective measure that provides a functional measure of a person’s cognitive status and correlates with the Mini-Mental Status Examination18), Depressive Severity Index (measure of depression severity), Mania Scale (measure of elevated mood disturbances), Positive Symptoms Scale (measure of severity of psychosis), Risk of Harm to Others Scale (measure of the level of risk of harm to others), Self Care Index (measure of the risk that a person will be unable to care for themselves due to presence of psychiatric symptoms), and Severity of Self-harm Score (measure of severity of person’s risk of self-harm). From the ODB data set, we extracted information on outpatient medications dispensed 120 days prior to admission for eligible individuals. The remaining databases (OHIP, NACRS, CIHI-DAD) provided information on medical comorbidities, as well as past-year number of psychiatric and/or medical emergency department visits, psychiatric and/or medical inpatient admissions, outpatient visits to psychiatrist, and outpatient visits to family physician for medical and/or psychiatric reasons.

Statistical Analyses

We first described characteristics of individual patients who did and did not receive ECT during the study period. We compared groups using standardized differences, which describes between-group differences in units of standard deviation.19 This measure was selected, rather than a P value, because it is not influenced by sample size and therefore is preferred in large cohorts where small, insignificant differences would be statistically significant using a P value approach.19 An absolute SD of >0.10 is considered a meaningful difference.19

Next, to identify patient-level characteristics associated with receiving inpatient ECT, we used hospital admission data—which allows for multiple admissions per patient—and applied a multivariable logistic regression model with receipt of ECT (yes/no) at each admission being the outcome. A generalized estimating equation (GEE) with an exchangeable correlation structure was incorporated to account for correlation among outcomes arising from multiple admissions from the same patient. Continuous covariates were discretized into clinically meaningful categories (e.g., deciles for age) to account for nonlinear relationships. All categorical covariates were assessed for sparse data. The main multivariable model included all covariates except prescription medication use prior to admission as this was available only for individuals eligible for public drug benefits. We assessed model discrimination using the c-statistic and conducted a complete case analysis because missing data were uncommon (<1%). We also assessed for multicollinearity in our model to ensure tolerance was <0.2 for all covariates included in the model.

Using identical methods as the main multivariable model, two additional models, restricted to individuals for whom all medication prescription data were available and stratified by age, were also generated that included prescription medication as a covariate. Models for individuals aged ≥65 (all Ontarians ≥65 receive public drug coverage) and individuals aged <65 (mainly individuals who receive social assistance or disability support) were generated separately given differences in reasons for public drug coverage differ by age-group.

All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.) with referent categories for multilevel categorical variables being the largest group and for binary variables being the absence of the condition. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons as this was a descriptive study and our focus was on effect size rather than statistical significance.20 This study was reported in accordance with STROBE guidelines.21

Role of Funding Source

The study sponsor had no role in study design or decision to publish this study. The corresponding author had full access to all data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics

From 75,429 unique hospital admissions for depression, 6,899 involved treatment with ECT (9.2%). This included 53,174 unique patients, of whom 5,043 (9.5%) received ECT during at least 1 admission. In univariate analyses, patients who received ECT were older, more likely to be female, married or partnered, and living in a high-income neighborhood than individuals who did not receive ECT (Table 1). Those who received ECT, more frequently had unipolar (vs. bipolar or unspecified) depression, were more frequently admitted due to inability to care for self, were older at their first hospital admission, and were more frequently incapable of consenting to some form of psychiatric treatment (ECT or otherwise) than those who never received ECT. They more frequently had depression with psychotic features and cognitive disorders but less frequently had a substance use disorder. We attempted to include catatonia as a comorbidity; however, <1% of admissions had this diagnostic code listed. They had higher rates of most medical comorbidities and were more likely to have publicly funded drug coverage. ECT-treated patients also had higher (worse) scores on ADL, Self-care, and Depressive Symptom Scales. They had more outpatient visits to psychiatrists and psychiatric hospitalizations within 12 months preceding admission. Among those with information on prescription medication use prior to admission, ECT-treated patients had more psychotropic medication prescriptions (e.g., antidepressant, antipsychotic, benzodiazepine, and lithium) with the exception of anticonvulsants (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparing Distributions of Characteristics among Individuals Who Received versus Who Did Not Receive Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT).

| Baseline Characteristics: n (%) | No ECT Treatment (n = 48,131) | ECT Treatment (n = 5,043) | Absolute Standardized Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |||

| Mean age ± SD (years) | 44 ± 17 | 56 ± 17 | 0.75 |

| Female sex | 27,632 (57.4%) | 3,241 (64.3%) | 0.14 |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married | 20,532 (42.7%) | 1,198 (23.8%) | 0.41 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 10,193 (21.2%) | 1,327 (26.3%) | 0.12 |

| Married/partnered | 17,401 (36.2%) | 2,518 (49.9%) | 0.28 |

| Education level | |||

| Less than high school | 9,243 (19.2%) | 912 (18.1%) | 0.03 |

| High school | 13,132 (27.3%) | 1,220 (24.2%) | 0.07 |

| Any postsecondary | 20,686 (43.0%) | 2,335 (46.3%) | 0.07 |

| Unknown | 5,064 (10.5%) | 575 (11.4%) | 0.03 |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 14,604 (30.3%) | 954 (18.9%) | 0.27 |

| Unemployed, seeking employment | 4,355 (9.0%) | 221 (4.4%) | 0.19 |

| Unemployed, not seeking employment | 18,874 (39.2%) | 2,210 (43.8%) | 0.09 |

| Other | 9,232 (19.2%) | 1,559 (30.9%) | 0.27 |

| Unknown | 1,065 (2.2%) | 99 (2.0%) | 0.02 |

| Urban dwelling | 43,211 (89.8%) | 4,554 (90.3%) | 0.02 |

| Neighborhood income quintile | |||

| 1 (lowest) | 13,243 (27.5%) | 1,118 (22.2%) | 0.12 |

| 2 | 10,360 (21.5%) | 1,009 (20.0%) | 0.04 |

| 3 | 9,044 (18.8%) | 967 (19.2%) | 0.01 |

| 4 | 8,340 (17.3%) | 977 (19.4%) | 0.05 |

| 5 (highest) | 6,915 (14.4%) | 952 (18.9%) | 0.12 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Depression type | |||

| Unipolar | 30,556 (63.5%) | 4,109 (81.5%) | 0.41 |

| Bipolar | 9,645 (20.0%) | 733 (14.5%) | 0.15 |

| Unspecified | 7,930 (16.5%) | 201 (4.0%) | 0.42 |

| Reason for admission | |||

| Problem with addiction/dependency | 8,660 (18.0%) | 354 (7.0%) | 0.34 |

| Forensic/justice/other | 2,753 (5.7%) | 228 (4.5%) | 0.05 |

| Specific psychiatric symptoms | 36,751 (76.4%) | 4,185 (83.0%) | 0.17 |

| Threat to others | 5,158 (10.7%) | 227 (4.5%) | 0.24 |

| Threat to self | 30,454 (63.3%) | 2,562 (50.8%) | 0.25 |

| Inability to care for self due to illness | 14,748 (30.6%) | 2,033 (40.3%) | 0.2 |

| Involuntary admission | 7,860 (16.3%) | 601 (11.9%) | 0.13 |

| Incapable to consent to treatment | 1,573 (3.3%) | 413 (8.2%) | 0.21 |

| Age at first psychiatric hospitalization | |||

| 0 to 14 years | 1,463 (3.0%) | 84 (1.7%) | 0.09 |

| 15 to 24 years | 12,722 (26.4%) | 669 (13.3%) | 0.33 |

| 25 to 44 years | 19,158 (39.8%) | 1,827 (36.2%) | 0.07 |

| 45 to 64 years | 11,564 (24.0%) | 1,528 (30.3%) | 0.14 |

| 65+ years | 3,217 (6.7%) | 934 (18.5%) | 0.36 |

| Eligible for public drug coverage | 20,391 (42.4%) | 3,005 (59.6%) | 0.35 |

| Mean body mass index ± SD (kg/m2) | 27.1 ± 7.4 | 27.4 ± 7.3 | 0.04 |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | |||

| Anxiety disorder | 8,226 (17.1%) | 1,065 (21.1%) | 0.1 |

| Depression with psychotic features | 5,945 (12.4%) | 1,105 (21.9%) | 0.26 |

| Nonaffective psychotic disorder | 1,443 (3.0%) | 78 (1.5%) | 0.1 |

| Personality disorder | 7,282 (15.1%) | 797 (15.8%) | 0.02 |

| Substance use disorder | 8,346 (17.3%) | 348 (6.9%) | 0.32 |

| PTSD or trauma-related disorder | 1,384 (2.9%) | 148 (2.9%) | 0 |

| Eating disorder | 472 (1.0%) | 62 (1.2%) | 0.02 |

| Cognitive disorder | 1,074 (2.2%) | 383 (7.6%) | 0.25 |

| Medical comorbidities | |||

| Respiratory | |||

| Asthma | 10,525 (21.9%) | 974 (19.3%) | 0.06 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5,545 (11.5%) | 781 (15.5%) | 0.12 |

| Cardiac | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 1,090 (2.3%) | 219 (4.3%) | 0.12 |

| Myocardial infarction | 688 (1.4%) | 100 (2.0%) | 0.04 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 5,000 (10.4%) | 869 (17.2%) | 0.2 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 578 (1.2%) | 133 (2.6%) | 0.1 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 3,412 (7.1%) | 609 (12.1%) | 0.17 |

| Gastrointestinal | |||

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 244 (0.5%) | 24 (0.5%) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal bleed | 883 (1.8%) | 114 (2.3%) | 0.03 |

| Neurologic | |||

| Parkinson’s disease | 240 (0.5%) | 94 (1.9%) | 0.13 |

| Epilepsy | 2,291 (4.8%) | 259 (5.1%) | 0.02 |

| Stroke | 1,855 (3.9%) | 282 (5.6%) | 0.08 |

| Endocrine, hematologic, and autoimmune | |||

| Hypothyroidism | 3,484 (7.2%) | 613 (12.2%) | 0.17 |

| Diabetes | 6,520 (13.5%) | 1,046 (20.7%) | 0.19 |

| Thromboembolic disease | 814 (1.7%) | 117 (2.3%) | 0.04 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 509 (1.1%) | 102 (2.0%) | 0.08 |

| Renal | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | 1,981 (4.1%) | 351 (7.0%) | 0.12 |

| Musculoskeletal | |||

| Hip fracture | 167 (0.3%) | 50 (1.0%) | 0.08 |

| Osteoporosis | 1,727 (3.6%) | 397 (7.9%) | 0.19 |

| Osteoarthritis | 8,150 (16.9%) | 1,300 (25.8%) | 0.22 |

| Other | |||

| HIV | 183 (0.4%) | 19 (0.4%) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 11,709 (24.3%) | 2,172 (43.1%) | 0.4 |

| Visual impairment | 299 (0.6%) | 37 (0.7%) | 0.01 |

| Hearing impairment | 2,237 (4.6%) | 349 (6.9%) | 0.1 |

| Falls | 3,593 (7.5%) | 323 (6.4%) | 0.04 |

| Psychiatric and functional scales (Mean ± SD) | |||

| Activity of Daily Living Hierarchy Scale | 0.17 ± 0.66 | 0.45 ± 1.10 | 0.31 |

| Aggressive Behavior Scale | 0.57 ± 1.62 | 0.41 ± 1.33 | 0.11 |

| Anhedonia Scale | 4.49 ± 4.12 | 6.68 ± 4.27 | 0.52 |

| Cognitive Performance Scale | 0.39 ± 0.84 | 0.77 ± 1.23 | 0.35 |

| Depressive Severity Index | 5.01 ± 4.00 | 6.28 ± 4.28 | 0.31 |

| Mania Scale | 2.26 ± 3.39 | 1.54 ± 2.53 | 0.24 |

| Positive Symptoms Scale | 2.22 ± 3.48 | 1.79 ± 2.95 | 0.13 |

| Risk of Harm to Others | 1.35 ± 1.52 | 1.02 ± 1.20 | 0.24 |

| Self-care Index | 1.44 ± 1.55 | 1.90 ± 1.70 | 0.28 |

| Severity of Self-harm Scale | 2.56 ± 1.81 | 2.32 ± 1.83 | 0.13 |

| Past-year health service use (Median IQR) | |||

| Mental health | |||

| Outpatient visits to psychiatrist | 1 (0 to 5) | 6 (2 to 12) | 0.81 |

| Outpatient visits to family physician | 1 (0 to 4) | 2 (0 to 5) | 0.14 |

| Emergency visits | 0 (0 to 1) | 0 (0 to 1) | 0.09 |

| Hospitalizations | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0 to 1) | 0.57 |

| Nonmental health | |||

| Outpatient visits to family physician | 4 (2 to 9) | 5 (2 to 10) | 0.1 |

| Emergency visits | 1 (0 to 2) | 0 (0 to 2) | 0.08 |

| Hospitalizations | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0 to 0) | 0.1 |

Note: For individuals who never received ECT, we used their characteristics from the first admission of the study period, and for individuals who received ECT, we used their characteristics from the first ECT they received ECT. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; SD = standard deviation.

Table 2.

Psychotropic Medication Prescriptions for Patients Eligible for Public Drug Coverage.

| Medication | No ECT Treatment | ECT Treatment | Absolute Standardized Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greater than or equal to 65 years old | n = 5,479 | n = 1,681 | |

| Anticonvulsant | 647 (11.8%) | 194 (11.5%) | 0.01 |

| Antidepressant | 3988 (72.8%) | 1475 (87.8%) | 0.38 |

| Antipsychotic | 2216 (40.4%) | 1125 (66.9%) | 0.55 |

| Benzodiazepine | 2737 (50.0%) | 937 (55.7%) | 0.12 |

| Cholinesterase inhibitor | 317 (5.8%) | 127 (7.6%) | 0.07 |

| Lithium | 349 (6.4%) | 152 (9.0%) | 0.1 |

| Less than 65 years old on social assistance | n = 14,912 | n = 1,324 | |

| Anticonvulsant | 3323 (22.3%) | 307 (23.2%) | 0.02 |

| Antidepressant | 9306 (62.4%) | 960 (72.5%) | 0.22 |

| Antipsychotic | 7744 (51.9%) | 847 (64.0%) | 0.25 |

| Benzodiazepine | 6939 (46.5%) | 782 (59.1%) | 0.25 |

| Cholinesterase inhibitor | 26 (0.2%) | 8 (0.6%) | 0.07 |

| Lithium | 1446 (9.7%) | 174 (13.1%) | 0.11 |

Note: For individuals who never received ECT, we used their characteristics from the first admission of the study period, and for individuals who received ECT, we used their characteristics from the first ECT they received ECT. ECT = electroconvulsive therapy.

Multivariable Models

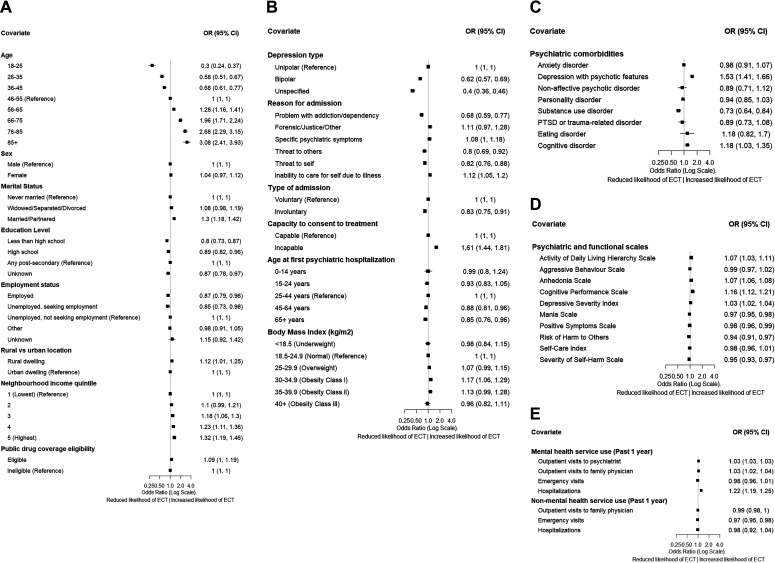

Estimates of adjusted associations from the multivariable logistic GEE model are presented in Figure 1. The c-statistic for the primary regression model was 0.82, and no variable had tolerance <0.2 indicating multicollinearity was not problematic.

Figure 1.

Characteristics associated with receiving inpatient electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)—as represented by adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI)—for (A) sociodemographic characteristics, (B) clinical characteristics, (C) psychiatric comorbidities, (D) psychiatric and functional assessment scales, and (E) health service utilization. Greater OR indicates higher likelihood an individual receives ECT.

Sociodemographic factors

Adjusted odds of ECT treatment increased with age and were also higher for individuals who were married or partnered versus never married, who had achieved any postsecondary education versus high school or less, who lived in a rural versus urban dwelling, who lived in the highest versus lowest neighborhood income quintile, and were eligible versus ineligible for public drug coverage.

Illness severity

Adjusted odds of ECT treatment increased with number of prior psychiatric hospitalizations and number of outpatient visits to a psychiatrist in the year preceding hospital admission. Adjusted odds of receiving ECT were also higher for individuals with more severe depressive symptoms (assessed by Depressive Severity Index), more social withdrawal (assessed by Anhedonia Scale), worse impairment in their ADLs (assessed by Activity of Daily Living Hierarchy Scale), and worse functional impairment due to baseline cognition (assessed by Cognitive Performance Scale). Adjusted odds of receiving ECT were lower for individuals with more severe mania (assessed by the Mania Scale), more psychotic symptoms (assessed by Positive Symptoms Scales), and more aggressive behavior toward others (assessed by Risk of Harm to Others Scale) or themselves (assessed by Severity of Self-harm Scale). The odds of ECT were also greater for those admitted due to inability to care for self due to illness versus other reasons, and for those incapable versus capable to consent to treatment.

Diagnosis and comorbidity

Adjusted odds of receiving ECT were higher for individuals with unipolar depressive disorder versus bipolar or unspecified depression, as well as a diagnosis of depression with psychotic features versus without psychotic features. Factors associated with reduced odds of receiving ECT were admission due to substance use (vs. other reasons), involuntary admission (vs. voluntary), diagnosis of substance use disorder (vs. not), diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, previous stroke, or falls (Supplemental Figure S1).

Additional Analyses

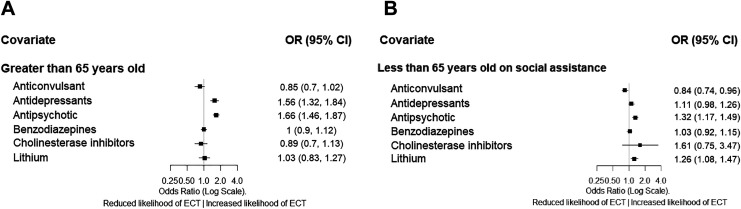

For individuals with prescription medication information (Figure 2), in those ≥65 years, a prescription for antidepressant or antipsychotic was associated with increased odds of ECT, while for individuals <65 years on social assistance, a prescription for antipsychotic medication was associated with increased odds of ECT, and a prescription for anticonvulsant medication was associated with reduced odds of ECT. The subgroup analysis for individuals <65 years on social assistance does not account for clustering as the GEE algorithm failed to converge in this subgroup.

Figure 2.

Prescription medications associated with receiving inpatient electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)—as represented by odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI)—for (A) individuals 65 years and older and (B) individuals under 65 years old on social assistance (naive analysis). Greater OR indicates higher likelihood an individual receives ECT.

Discussion

The current work provides valuable information regarding the real-world use of ECT and is based on robust analyses using population-level data from a large jurisdiction with detailed clinical information rarely available in administrative health databases. We found that nearly 10% of patients admitted for depression for longer than 3 days ultimately received inpatient ECT. Patient-level characteristics differed markedly between those who did and did not receive ECT on an inpatient psychiatric unit. While some characteristics including diagnosis, illness severity and comorbidity were consistent with best clinical practice and clinically sensible, several nonclinical factors were also strongly associated with receipt of ECT. These latter characteristics are surprising and require further investigation as they may represent important and modifiable disparities in access to ECT treatment.

Our findings indicate that illness severity characteristics impact whether an individual will receive inpatient ECT. Higher depression severity, more social withdrawal, more functional impairment in ADLs, more psychiatric hospitalizations, and more outpatient psychiatrist visits were associated with increased odds of receiving ECT. Similarly, other clinical factors such as depression with psychotic features increased the likelihood of receiving ECT and several medical comorbidities or comorbid substance use disorders reduced the likelihood of receiving ECT. These findings align with clinical practice guideline recommendations in which ECT is recommended for severe, refractory depression (e.g., TRD) or for depression with psychotic features.7 Unexpectedly, we found admissions due to self-harm risk and higher scores on a scale assessing self-harm risk were associated with lower likelihood of receiving ECT. One potential explanation for this finding is that these results may be capturing self-harm risk due to personality pathology (e.g., borderline personality disorder), for which ECT is noticeably less effective.22,23 Similarly surprising is our finding that bipolar disorder was strongly associated with reduced likelihood of receiving ECT despite evidence that bipolar and unipolar depression respond similarly to ECT.24 One potential explanation is that individuals with bipolar depression are often treated with mood stabilizers, such as lithium or anticonvulsants,25 which may interfere with the efficacy of ECT or increase risk of complications.26,27 While there are no absolute contraindications to ECT, medical comorbidities or active substance use may increase the safety risk of providing treatment with ECT, likely due to risks associated with general anesthesia, and reduced odds of use in the presence of these characteristics reflect appropriate practice patterns.7,28

A noteworthy finding in this study is that incapacity to consent to treatment was associated with increased odds of receiving ECT. To our knowledge, though studies have examined the role of capacity in treatment outcomes for depressed patients, there are no studies examining capacity on the likelihood of ECT.29 In Ontario, Canada, there is a well-developed legal framework designed to protect the right of individuals to make autonomous treatment decisions. When an individual is declared incapable to consent to a specific psychiatric treatment (ECT or otherwise), they are notified with a legislatively defined form and have the opportunity to challenge this finding at an independent tribunal in which they will receive legal representation at no cost. If the finding of incapacity is upheld or the individual does not challenge the finding of incapacity then informed consent is provided by a substitute decision maker defined by legislation. As a result of this rigorous process, it is unlikely that the presence of incapacity to consent to a treatment (ECT or otherwise) is causally related to an increased use of ECT. Instead, treatment incapacity more likely serves as a marker for severe illness or psychotic symptoms (both clinical indications for ECT7) that are not captured by other measured covariates. An important indication for ECT, and one associated with treatment incapacity, is catatonia, a syndrome characterized by psychomotor disturbances, which often occurs in severe mood disorders.30,31 We could not assess the association of this comorbidity with ECT because the diagnostic code had a very low prevalence (<1%), which likely reflects both clinical underrecognition31 and undercoding in administrative health databases.

Factors like illness severity or comorbid conditions indicate clinical need or relative contraindications for ECT treatment. However, several characteristics that impacted the odds of receiving ECT in this study are considered “enabling resources” by health care utilization models that reflect logistical aspects of obtaining care.32 In this study, being unmarried, less educated, and living in a lower income area (i.e. enabling resources) each independently reduced the odds that a person would receive ECT, even after accounting for clinical factors and despite all patients being treated in the common environment of a psychiatric inpatient unit in a universal health care system where ECT and all inpatient care is publicly funded. These are important findings because, when access to medical care is determined by enabling resources, as opposed to need factors (e.g., illness severity), this may indicate inequitable access to medical care.32 Inequitable access to ECT has previously been suggested in the U.S. Veterans Affairs health system, where black race, particular geographic regions (e.g., South and West U.S.), and living near a facility that does not perform ECT were all associated with reduced odds of receiving treatment.10 Our findings are also consistent with a recent study from Denmark, which has a similar universal health care system to Canada, that found age and depression severity increase the likelihood of ECT, while alcohol use, being unmarried, and having low education decrease the likelihood of ECT.11 These consistent results from a variety of jurisdictions support our hypothesis that ECT use is driven by a combination of appropriate clinical factors and questionable nonclinical factors. Although our study used Canadian data, this finding that enabling resources influence receipt of ECT also likely applies to other health care systems who are seeking to improve equitable access to this important treatment.

The underlying mechanisms that explain the relationship between enabling resources and receipt of ECT are unknown but may involve factors at the patient, physician, and system level. For example, the finding that individuals with higher education are more likely to receive ECT—even after accounting for other factors—is unexpected and has a number of possible explanations. It is possible that the manner in which informed consent for ECT is obtained may not be suitable for individuals with a lower literacy level or that lower levels of education may reflect less trust in the health care system.33 Alternatively, individuals with less education may have less insight into their psychiatric symptoms,34 which may result in these patients being less likely to consent to an intensive treatment such as ECT. There may also be a provider bias against individuals with less education. Individuals with higher levels of education have previously been demonstrated to be more satisfied following ECT treatment,35 which over time may result in physicians preferentially selecting individuals with higher levels of education. It is also possible that the seemingly disparate characteristics increasing the odds of receiving inpatient ECT (e.g., living in a rural area, higher neighborhood income, being married) are connected by the fact that they reflect an individual’s membership in a community with higher levels of social capital. Social capital, which has been defined as “features of social life—networks, norms, and trust—that enable participants to act together more effectively to pursue shared objectives,”36 has been demonstrated to influence an individual’s ability to access care.37 Therefore, it may be that individuals living in communities with higher levels of social capital may be able to more effectively navigate a complex and challenging health care system to access effective treatments. Finally, providers, due to their concerns about whether people who have an initial course of ECT as inpatients will be able to navigate outpatient treatment, may also be more likely to recommend the treatment for people who have higher levels of social stability and resources.

Although our findings potentially indicate a concern with respect to equitable access to ECT treatment, we found that nearly 10% of inpatients with depression eventually received ECT. The prevalence of use in our study is similar to a study using data from 1993 in the United States, which found that 9.4% of inpatients with depression received ECT.38 However, a more recent study using administrative data from 2015 to 2017 in 9 different U.S. states, found that ECT was used in only 1.5% of inpatients with depression.39 A detailed analysis examining the declining use of ECT in general hospitals in the United States found the decline was due to fewer hospitals conducting ECT (70.5% in 1993 vs. 44.7% in 2009) as opposed to changing clinical characteristics over time (e.g., less severely ill patients being admitted).9 Although the current study did not examine temporal trends of ECT our results suggest that at least in Ontario, Canada, ECT is not underutilized in this severely ill population. However, there appear to be opportunities for improving equitable access to this important treatment.

Limitations

There are several limitations of this work to consider. First, we maintained our focus on only patient-level characteristics. Institutional- and provider-level characteristics and geographic variation may also play an important role in the receipt of ECT; however, the c-statistic of 0.82 does suggest that the discrimination of who will get ECT is quite high even using only the patient-level characteristics.8 Future work examining the use of ECT should include institutional characteristics (e.g., number of yearly ECT procedures) as well as geographic features (e.g., patient proximity to hospital with ECT machines) to better characterize the delivery and utilization of this important procedure. Second, we considered only inpatients with depression, which limits the generalizability of our findings to other conditions that can be treated with ECT, such as schizophrenia,40 or for other treatment locations (e.g., outpatients). Given that 80% of the ECT delivered in Ontario is provided to inpatients and that depression is the main indication for the procedure, we felt the emphasis on this population to be reasonable.15 Third, while we used data from the population of Ontario, our results may not be generalizable to different health care models, such as the United States, where insurance status may have a significant impact on the receipt of ECT.13 Last, while we had data on a wide variety of characteristics, we did not have detailed information on important characteristics, such as treatment resistance, which may result in residual confounding impacting our findings.41 In particular, our results could be partially impacted by unmeasured covariates including factors such as patient preferences, previous experience with ECT, or degree of treatment resistance. Given the stigma associated with ECT, further qualitative research on the role of patient preference will be important. However, many characteristics associated with receiving inpatient ECT (presence of psychotic features, increased age, symptom severity, etc.) are consistent with best clinical practice, which supports the validity of our overall model. This in turn lends greater confidence to our unexpected findings regarding characteristics suggestive of inequitable access to ECT treatment.

Conclusion

We found that nearly 1 in 10 patients hospitalized for depression in Ontario, Canada, received ECT. While receipt of ECT was associated with many clinically sensible factors, several unexpected sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., marital status, education level, neighborhood income quintile) that likely reflect logistical aspects in obtaining care, were associated with reduced likelihood of receiving ECT. Further research is needed to define mechanisms and identify solutions to ensure equitable access to ECT.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, Supplemental_Table_S1 for Patient-level Characteristics and Inequitable Access to Inpatient Electroconvulsive Therapy for Depression: A Population-based Cross-sectional Study: Caractéristiques au niveau du patient et accès inéquitable à la thérapie électroconvulsive pour patients hospitalisés by Tyler S. Kaster, Daniel M. Blumberger, Tara Gomes, Rinku Sutradhar, Zafiris J. Dasklakis, Duminda N. Wijeysundera and Simone N. Vigod in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgments

We thank IMS Brogan Inc. for use of their Drug Information Database. We thank the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) for their data. We thank Robin Santiago and Kinwah Fung for their assistance in this work.

Authors’ Note: Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by MOHLTC, CIHI, and IMS Brogan Inc. The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by CIHI. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed in the material are those of the author(s), and not necessarily those of CIHI. The data set from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While data sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the data set publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet prespecified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS. The full data set creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification. Kaster, Vigod, Blumberger, Gomes, Sutradhar, and Wijeysundera contributed to concept and design. Kaster, Vigod, Blumberger, Sutradhar, and Gomes contributed to acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data. Kaster, Vigod, Blumberger, Sutradhar, and Wijeysundera drafted the manuscript. Kaster, Vigod, Blumberger, Gomes, Sutradhar, Daskalakis, and Wijeysundera critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Kaster, Vigod, Gomes, and Sutradhar performed statistical analysis. Kaster, Vigod, and Blumberger contributed for administrative, technical, or material support. Vigod and Blumberger Supervised the study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Blumberger reports grants and nonfinancial support from Brainsway Ltd., nonfinancial support from MagVenture, nonfinancial support from Indivior, personal fees from Janssen, outside the submitted work. Dr. Gomes reports grants from Ontario Ministry of Health, outside the submitted work. Dr. Daskalakis reports grants and nonfinancial support from Brainsway Ltd., grants and nonfinancial support from MagVenture, outside the submitted work.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). This work was also supported by the University of Toronto Department of Psychiatry Clinician Scientist Program Norris Scholar Award. Dr Kaster is supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research Fellowship Award. Dr. Blumberger is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), National Institutes of Health—US (NIH), Weston Brain Institute, Brain Canada and the Temerty Family through the CAMH Foundation and the Campbell Research Institute. He received research support and in-kind equipment support for an investigator-initiated study from Brainsway Ltd. And he is the site principal investigator for three sponsor-initiated studies for Brainsway Ltd. He received in-kind equipment support from Magventure for this investigator-initiated study. He received medication supplies for an investigator-initiated trial from Indivior. He has participated in an advisory board for Janssen. Dr. Gomes is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Drug Policy Research & Evaluation. Dr. Sutradhar has no competing interests. Dr. Daskalakis has received research and equipment in-kind support for an investigator-initiated study through Brainsway Inc and Magventure Inc. He is supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Brain Canada and the Temerty Family and Grant Family and through the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) Foundation and the Campbell Institute. Dr. Wijeysundera is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, an Excellence in Research Award from the Department of Anesthesia at the University of Toronto, and the Endowed Chair in Translational Anesthesiology Research at St. Michael’s Hospital and University of Toronto. Dr Vigod is supported by Women’s College Hospital, the University of Toronto Department of Psychiatry and by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

ORCID iD: Daniel M. Blumberger, MD, MSc  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8422-5818

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8422-5818

Supplemental Material: The supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fava M. Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;53(8):649–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kellner CH, Knapp R, Husain MM, et al. Bifrontal, bitemporal and right unilateral electrode placement in ECT: randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(3):226–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Petrides G, Fink M, Husain MM, et al. ECT remission rates in psychotic versus nonpsychotic depressed patients: a report from CORE. J ECT. 2001;17(4):244–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kellner CH, Fink M, Knapp R, et al. Relief of expressed suicidal intent by ECT: a consortium for research in ECT study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(5):977–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Milev RV, Giacobbe P, Kennedy SH, et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 4. neurostimulation treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):561–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lemasson M, Haesebaert J, Rochette L, Eric P, Alain L, Simon P. Electroconvulsive therapy practice in the province of Quebec: linked health administrative data study from 1996 to 2013. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(7):465–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Case BG, Bertollo DN, Laska EM, et al. Declining use of electroconvulsive therapy in united states general hospitals. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(2):119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pfeiffer PN, Valenstein M, Hoggatt KJ, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy for major depression within the veterans health administration. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1–2):21–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jørgensen MB, Rozing MP, Kellner CH, Merete O. Electroconvulsive therapy, depression severity and mortality: data from the Danish national patient registry. J Psychopharmacol. 2020;34(3):273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilkinson ST, Rosenheck RA. Electroconvulsive therapy at a veterans health administration medical center. J ECT. 2017;33(4):249–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilkinson ST, Agbese E, Leslie DL, et al. Identifying recipients of electroconvulsive therapy: data from privately insured Americans. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(5):542–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Knight J, Jantzi M, Hirdes J, Terry R. Predictors of electroconvulsive therapy use in a large inpatient psychiatry population. J ECT. 2018;34(1):35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blumberger DM, Seitz DP, Herrmann N, et al. Low medical morbidity and mortality after acute courses of electroconvulsive therapy in a population-based sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(6):583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Juurlink D, Preyra C, Croxford R, et al. Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database: a validation study. Toronto (ON): Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hutchinson AM, Milke DL, Maisey S, et al. The resident assessment instrument-minimum data set 2.0 quality indicators: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10(1):166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jones K, Perlman CM, Hirdes JP, et al. Screening cognitive performance with the resident assessment instrument for mental health cognitive performance scale. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(11):736–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083–3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bender R, Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing—when and how? J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(4):343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kaster TS, Goldbloom DS, Daskalakis ZJ, Benoit HM Daniel MB. Electroconvulsive therapy for depression with comorbid borderline personality disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder: a matched retrospective cohort study. Brain Stimul. 2018;11(1):204–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Feske U, Mulsant BH, Pilkonis PA, et al. Clinical outcome of ECT in patients with major depression and comorbid borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161(11):2073–2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dierckx B, Heijnen WT, van den Broek WW, Tom KB. Efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy in bipolar versus unipolar major depression: a meta-analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(2):146–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) and international society for bipolar disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Virupaksha HS, Shashidhara B, Thirthalli J, Channaveerachari NK, Bangalore NG. Comparison of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) with or without anti-epileptic drugs in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2010;127(1–3):66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patel RS, Bachu A, Youssef NA. Combination of lithium and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is associated with higher odds of delirium and cognitive problems in a large national sample across the United States. Brain Stimul. 2020;13(1):15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moran S, Isa J, Steinemann S. Perioperative management in the patient with substance abuse. Surg Clin North Am. 2015;95(2):417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tor PC, Tan FJS, Martin D, Colleen L. Outcomes in patients with and without capacity in electroconvulsive therapy. J Affect Disord. 2020;266:151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-V. 5th ed. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fink M, Taylor MA. Catatonia: a clinician’s guide to diagnosis and treatment. Cambridge University Press. 2003. March 20. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511543777. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tsai TI, Yu WR, Lee SYD. Is health literacy associated with greater medical care trust? Int J Qual Heal care J Int Soc Qual Heal Care 2018;30(7):514–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yen CF, Chen CC, Lee Y, Tze-Chun T, Chih-Hung K, Ju-Yu Y. Insight and correlates among outpatients with depressive disorders. Compr Psychiatry 2005;46(5):384–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goodman JA, Krahn LE, Smith GE, Rummans TA, Pileggi TS. Patient satisfaction with electroconvulsive therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74(10):967–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Putnam R. The strange disappearance of civic America. Am Prospect. 1996:2434–2448. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hendryx MS, Ahern MM, Lovrich NP, McCurdy AH. Access to health care and community social capital. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(1):87–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Olfson M, Marcus S, Sackeim HA, Thompson J, Pincus HA. Use of ECT for the inpatient treatment of recurrent major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(1):22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Slade EP, Jahn DR, Regenold WT, Brady GC. Association of electroconvulsive therapy with psychiatric readmissions in US Hospitals. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(8):798–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kaster TS, Daskalakis ZJ, Blumberger DM. Clinical effectiveness and cognitive impact of electroconvulsive therapy for schizophrenia: a large retrospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(4):e383–e389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jepsen P, Johnsen SP, Gillman MW, Sørensen HT. Interpretation of observational studies. Heart. 2004;90(8):956–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, Supplemental_Table_S1 for Patient-level Characteristics and Inequitable Access to Inpatient Electroconvulsive Therapy for Depression: A Population-based Cross-sectional Study: Caractéristiques au niveau du patient et accès inéquitable à la thérapie électroconvulsive pour patients hospitalisés by Tyler S. Kaster, Daniel M. Blumberger, Tara Gomes, Rinku Sutradhar, Zafiris J. Dasklakis, Duminda N. Wijeysundera and Simone N. Vigod in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry