The second period of tobacco control studies in Turkey has been completed in 2008–2012. The third period is scheduled to be implemented between 2018 and 2023. Periodic studies are conducted to evaluate the effects and success of periods on tobacco control. One of these studies is the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS). The first of this research was published in 2012 and the last one was published in 2016.

This study aimed to assess Turkey’s fight against tobacco use in the light of the GATS.

In Turkey, the use of tobacco is negatively correlated with income in men; it is known to be positively correlated with education level in women [1, 2]. Similarly, smoking cessation success was shown to be positively correlated with income [3]. For this reason, the success of the national tobacco control program must be strengthened by social policy measures, such as increase in employment, reduction in income injustice and conditional cash transfer in the smoking cessation process, and gender equality practices for women-LGBTI+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans(gender), Intersex) groups, which need to be implemented.

As is known, according to the findings of the 2012 GATS, the rates of tobacco use in Turkey compared with 2008 decreased by 13.7% in women, 13.5% in men, and 13.4% in total [4]. Similarly, during 2008–2012, the use of hookahs decreased from 2.3% to 0.8%, smoking before the age of 15 years decreased from 19.6% to 16.1%, passive smoke exposure in restaurants decreased from 55.9% to 12.9%, and even with the absence of legal provisions, household smoke exposure decreased by 32% [4].

In contrast, the same research showed that health personnel’s asking for smoking status increased from 48.8% to 56.3%, health personnel’s recommendation to quit increased from 38.0% to 46.4%, and antismoking message on television increased from 85.5% to 91.4%, and as a reflection of these positive developments, the rate of thinking about quitting because of the warnings on cigarette packages increased by 14.4% in 2008–2012 [4].

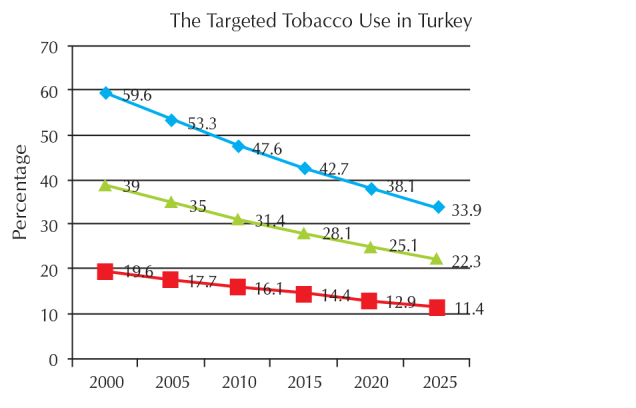

Turkey’s positive progress, achieved within a short time, was reflected in a positive way to the future projections by the World Health Organization (Figure 1) [5].

Figure 1.

Targeted tobacco use in Turkey

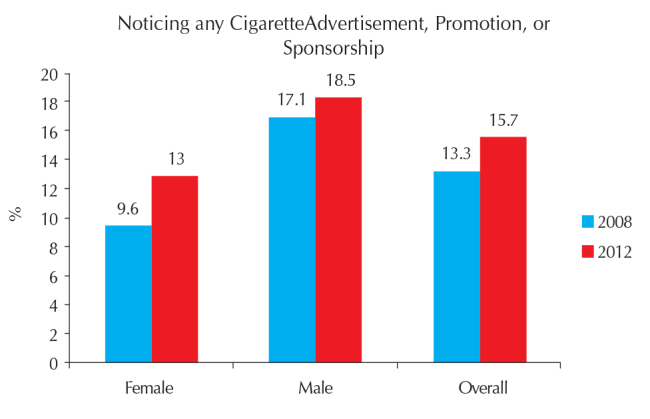

However, the GATS conducted in 2012, in addition to the positive developments, revealed the existence of increase in advertising, sponsorship, and promotions of the tobacco industry in Turkey (Figure 2) [4].

Figure 2.

Noticing any cigarette advertisement, promotion, or sponsorship

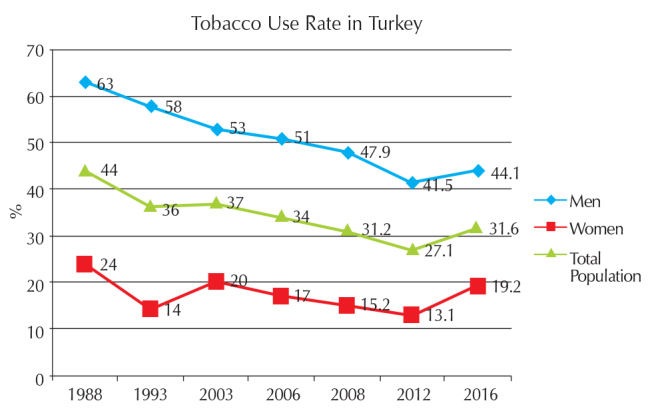

However, despite these problems, as of 2012, the use of tobacco had decreased steadily over the years in Turkey. The preliminary results of the recently announced 2016 GATS indicate that this downward trend has stopped, and that there has been an increase in the opposite direction after 2012*. According to the preliminary findings of this study, the rate of tobacco use in Turkey has increased in both men and women in 4 years after 2012 (Figure 3) [6].

Figure 3.

Tobacco use rate in Turkey

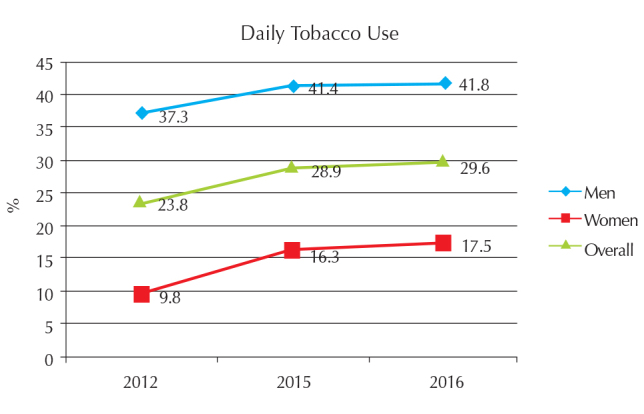

In fact, this increase was not detected in 2016 only. Considering the number of people who smoke every day, there was also an increase before 2016 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Daily tobacco use in Turkey

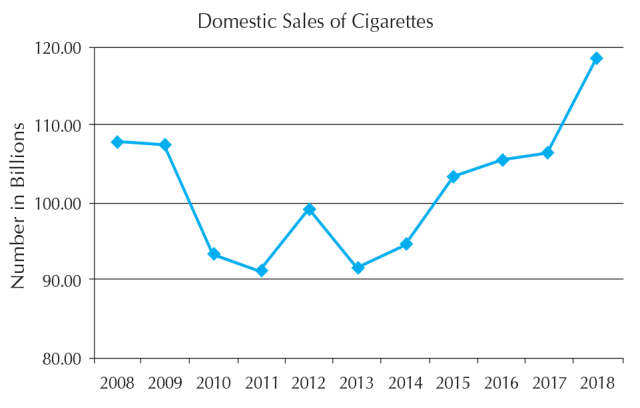

Undoubtedly, the increase observed during 2012–2016 is a reflection of increased stability in Turkey’s domestic sales of cigarettes owing to the policies implemented between 2011 and 2018 (Figure 5) [7].

Figure 5.

Domestic sales of cigarettes

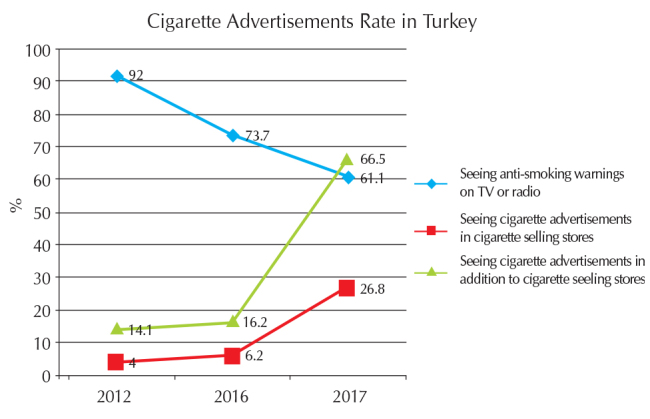

The 2016 GATS also pointed out that within the last 4 years, smoking cessation in Turkey decreased from 27.2% to 13.6%, making cessation advice of health personnel decreased from 42.9% to 40.1%, thinking about quitting smoking decreased from 55.2% to 32.8%, visual warning against smoking on television or radio decreased from 92.0% to 73.7%, and seeing health warnings on cigarette packets decreased from 94.3% to 83.3%, but advertising in cigarette selling stores increased from 4.0% to 6.2%, and cigarette advertisements, in addition to cigarette selling stores, increased from 14.1% to 16.2% [6].

At this stage, it is clear that the positivity detected in young people in 2017 needs to be discussed. Because despite the success achieved in the period between 2008 and 2012, the use of tobacco increased among young people, in contrast to adults. In other words, the success observed in adults could not be achieved in young people. However, the results of the Youth Tobacco Survey conducted in 2017 indicate that in contrast to the increase in tobacco use among adults during 2012–2016, the use in young people decreased during this period [8].

It is interesting to note that when the findings of the 2017 survey, which showed that tobacco use was reduced among young people, were evaluated together with the findings of adult tobacco research in previous years, it is understood that the rate of seeing antismoking warnings on television or radio decreased in years in Turkey; in contrast, in addition to cigarette selling stores, the rate of cigarette advertisements increased (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Cigarette advertisements rate in Turkey

Given the level of exposure of young people to the media and social media, despite the increasing tobacco advertising, data on tobacco use among young people showing a decrease in 2017 are open to questioning.

Moreover, when the results of the 2016 GATS and the GATSs conducted in previous years are compared with respect to the same parameters, the rates of tobacco use and thinking of smoking cessation in Turkey appear to deteriorate at a much higher rate in female gender than in male gender. Indeed, in 2012, the rate of thinking about quitting smoking because of health warnings in cigarette packages was 51.6% for men and 57.5% for women, whereas in 2016, these rates were 31.9% and 29.1%, respectively. In other words, in the last 4 years, the rate of thinking about quitting smoking decreased by 38.2% in men and 49.4% in women. In the same period, tobacco use rates increased by 2.6% in men and 6.1% in women. Although the increase in male gender was 6% compared with the male population smoking tobacco in 2012, this increase in female gender was 47%. Over time, this situation developing to the detriment of women is a reflection of the worsening gender inequalities in the year in Turkey.

Finally, in the light of the findings of the 2016 GATS, it is observed that tobacco exposure rates in closed areas have continued to decrease compared with previous years. In other words, the problems of adapting to the MPOWER strategy [9], which has been implemented, have diminished, although not disappearing over the years. However, unfortunately, despite the implementation of MPOWER strategies, the rates of tobacco use are also increasing in both genders in Turkey. This situation demonstrates that the terms for the success of the national tobacco control program are social policy measures and strengthening of gender equality practices for women-LGBTI+ groups, which need to be implemented. Similarly, the 2016 GATS points out that the demand limiting achievements in tobacco control in Turkey, as an example of liberalizing the country through privatizations of tobacco areas, cannot be permanent, and that, therefore, MPOWER strategies should be empowered with the proposals developed from the experience of Turkey [10] to refine the supply side.

In this sense, supply reduction methods can be summarized as reducing product diversity, prohibiting additives including menthol, establishing the marketing network independent of industry, and applying negative incentives to the tobacco industry [11].

Footnotes

Because the results of this study are accessible in factsheet format, it is not possible to carry out further analysis on published data.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - O.E., O.K., B.S., P.B., P.D.Ç., S.A., A.G.D., F.Ç.U.K., E.D.; Design - O.E., O.K., E.D.; Supervision - O.K., B.S., P.B., P.D.Ç., S.A., A.G.D., F.Ç.U.K.; Materials - O.E.; Data Collection and/or Processing - O.E.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - O.E., O.K., B.S., E.D.; Literature Review - O.E., O.K., B.S., P.B., P.D.Ç., S.A., A.G.D., F.Ç.U.K., E.D.; Writing - O.E., O.K., B.S., P.B., P.D.Ç., S.A., A.G.D., F.Ç.U.K., E.D.; Critical Review - O.E., O.K., B.S., P.B., P.D.Ç., S.A., A.G.D., F.Ç.U.K., E.D.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.US National Cancer Institute & WHO. The Economics of Tobacco and Tobacco Control. 2016. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/21/

- 2.WHO. European Tobacco Use Trends Report 2019. 2019. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/402777/Tobacco-Trends-Report-ENG-WEB.pdf?ua=1.

- 3.Öztuna F, Çan G, Ayık S, Özlü T, Yılmaz İ. Long-term results of smoking cessation therapy. J Med Sci. 2013;33:1201–8. doi: 10.5336/medsci.2012-31326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Public Health Institution of Turkey. Global Adult Tobacco Survey Turkey 2012. 2014. https://www.who.int/tobacco/surveillance/survey/gats/report_tur_2012.pdf?ua=1.

- 5.WHO. WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking 2000–2025. 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272694/9789241514170-eng.pdf?ua=1.

- 6.CDC. Global Tobacco Surveillance System Data. https://nccd.cdc.gov/GTSSDataSurveyResources/Ancillary/DataReports.aspx?CAID=1.

- 7.Tarım ve Orman Bakanlığı Tütün ve Alkol Dairesi Başkanlığı. Tütün Mamulleri İstatistikleri. https://www.tarimorman.gov.tr/TADB/Menu/22/Tutun-Ve-Tutun-Mamulleri-Daire-Baskanligi.

- 8.TC Sağlık Bakanl ığı Halk Sağlığı Genel Müdürlüğü. Küresel Gençlik Tütün Araştırması (KGTA-2017) 2017. https://hsgm.saglik.gov.tr/depo/birimler/tutun-mucadele-bagimlilik-db/duyurular/KGTA-2017_pdf.pdf.

- 9.WHO. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic. 2008. https://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/gtcr_download/en/

- 10.Elbek O, Kılınç O, Aytemur ZA, et al. Tobacco control in Turkey. Turk Thorac J. 2015;16:141–150. doi: 10.5152/ttd.2014.3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evrengil E. Policy conflict in FCTC implementation: investment and export incentives granted to tobacco industry in Turkey. STED. 2017;26(Special Issue):18–29. [Google Scholar]