Abstract

Pharmacodynamic efficacy of drugs to activate their receptors is a key determinant of drug effects, and intermediate-efficacy agonists are often useful clinically because they retain sufficient efficacy to produce therapeutically desirable effects while minimizing undesirable effects. Molecular mechanisms of efficacy are not well understood, so rational drug design to control efficacy is not yet possible; however, receptor theory predicts that fixed-proportion mixtures of an agonist and antagonist for a given receptor can be adjusted to precisely control net efficacy of the mixture in activating that receptor. Moreover, the agonist proportion required to produce different effects provides a quantitative scale for comparing efficacy requirements across those effects. To test this hypothesis, the present study evaluated effectiveness of fixed-proportion agonist/antagonist mixtures to produce in vitro and in vivo effects mediated by μ-opioid receptors (MOR) and cannabinoid type 1 receptors (CB1R). Mixtures of 1) the MOR agonist fentanyl and antagonist naltrexone and 2) the CB1R agonist CP55,940 and antagonist/inverse agonist rimonabant were evaluated in an in vitro assay of ligand-stimulated guanosine 5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate binding and an in vivo assay of thermal nociception in mice. For both agonist/antagonist pairs in both assays, increasing agonist proportions produced graded increases in maximal mixture effects, and lower agonist proportions were sufficient to produce in vivo than in vitro effects. These findings support the utility of agonist-antagonist mixtures as a strategy to control net efficacy of receptor activation and to quantify and compare efficacy requirements across a range of in vitro and in vivo endpoints.

Significance Statement

Manipulation of agonist proportion in agonist/antagonist mixtures governs net mixture efficacy at the target receptor. Parameters of agonist/antagonist mixture effects can provide a quantitative metric for comparison of efficacy requirements across a wide range of conditions.

Introduction

The efficacy of a drug to activate transduction pathways coupled to its target receptor is a key pharmacodynamic determinant of both its therapeutic effectiveness and its safety (Blumenthal, 2018). Among opioids, for example, relatively high-efficacy opioids such as methadone, fentanyl, and morphine are therapeutically useful to treat severe pain, and methadone is also approved as a maintenance medication to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) and mitigate withdrawal in highly dependent opioid users; however, these drugs also have sufficient MOR efficacy to produce lethal respiratory depression and overdose death (Toombs and Kral, 2005; Yaksh and Wallace, 2018; Kreek et al., 2019). Conversely, the intermediate-efficacy MOR agonist buprenorphine is less effective for treatment of severe pain or highly dependent patients with OUD, but it can nonetheless produce analgesia and clinical benefit in less dependent patients with OUD, and it is safer than high-efficacy opioids because it lacks sufficient efficacy to produce lethal respiratory depression even at very high doses (Raffa et al., 2014; Yaksh and Wallace, 2018; Kreek et al., 2019). Moreover, recent studies suggest that relatively low efficacy may contribute to the apparent bias and improved safety profiles of so-called biased MOR agonists (Gillis et al., 2020). These examples with opioids illustrate the more general principle that agonist efficacy exists on a continuum and that it is at least theoretically possible to develop drugs with limited efficacy sufficient to produce desired therapeutic effects while minimizing risk of undesired effects that require higher efficacy. Intermediate-efficacy medications have also been developed for other targets, including receptors for dopamine (Tamminga and Carlsson, 2002), serotonin (Yocca, 1990), norepinephrine (Lipworth and Grove, 1997), and acetylcholine (Rollema et al., 2007).

Although research on molecular mechanisms that govern efficacy is advancing, these mechanisms remain incompletely understood (Ide et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2015; Sounier et al., 2015; Sutcliffe et al., 2017). As a result, the discovery of low- and intermediate-efficacy agonists is often serendipitous despite their therapeutic potential. An alternative approach to controlling efficacy of a pharmacological treatment at a receptor target has been suggested by principles of receptor theory (Cornelissen et al., 2018). Specifically, receptor theory predicts that proportions of a competitive agonist and antagonist in an agonist/antagonist mixture can be manipulated to precisely control the net efficacy of the mixture such that increasing agonist proportions increase mixture efficacy. These predictions have been confirmed using mixtures of a high-efficacy MOR agonist (fentanyl) and an MOR antagonist (naltrexone) evaluated on behavioral endpoints in rhesus monkeys and rats (Cornelissen et al., 2018; Schwienteck et al., 2019). The clinical potential of such mixtures as pharmacotherapies is complicated by any pharmacokinetic differences in the agonist and antagonist components of the mixture; however, these mixtures can be especially useful for basic science applications that include quantification of efficacy requirements for different drug effects and determination of target efficacies that might be optimal for producing therapeutic effects while minimizing risk of undesirable effects.

The goal of the present study was to extend our previous investigations on agonist/antagonist mixtures in two ways. First, to determine whether agonist/antagonist mixture effects would extend to in vitro biochemical measures of efficacy, the effects of fentanyl/naltrexone mixtures were compared on endpoints of 1) in vitro activation of mouse MOR using an assay of agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding and 2) in vivo antinociception in mice using an assay of warm water tail withdrawal (Selley et al., 1998; Yuan et al., 2013). Second, to determine whether agonist/antagonist mixtures targeting a nonopioid receptor would also produce effects predicted by receptor theory, we used the same two assays to compare effects produced by mixtures of the high-efficacy cannabinoid type 1 receptor (CB1R) agonist CP55,940 and antagonist/inverse agonist rimonabant (Breivogel et al., 1998; Grim et al., 2016; Grim et al., 2017). We hypothesized that maximal mixture effects in each assay would vary as an orderly function of agonist-to-antagonist proportion such that mixtures with increasing agonist proportions would produce increasing maximal effects. Additionally, as outlined in Fig. 1, we predicted that analysis of the curve relating agonist proportion to maximal mixture effects in each assay would permit quantification of MOR and CB1R efficacy requirements to produce effects in each assay, as they have for previous in vivo endpoints (Cornelissen et al., 2018; Schwienteck et al., 2019).

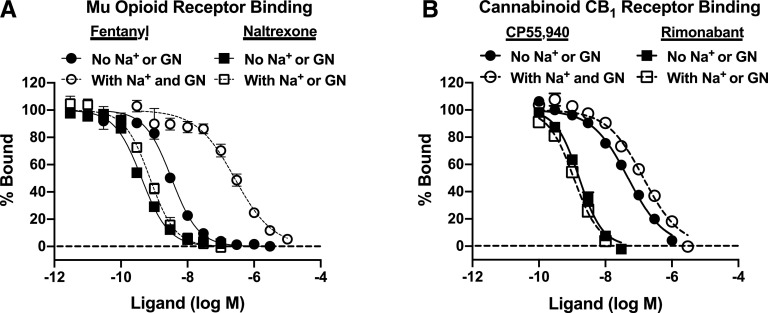

Fig. 1.

Progression of steps tested empirically in this study. (A) In considering effects of an agonist on a population of its target receptor, increasing agonist doses will produce increasing levels of total receptor activation. The Furchgott equation for receptor theory predicts that fixed-proportion mixtures of the agonist with an antagonist for the same receptor will produce progressively lower maximal effects that decrease as the agonist proportion in the mixture decreases [for equation, see Cornelissen et al. (2018)]. (B) Receptor activation is transduced by biologic systems into different biologic endpoints measured by different experimental procedures. Each endpoint and associated procedure for its measurement has a threshold level of receptor activation required for detection of an effect and a ceiling level of receptor activation at which the effect plateaus. The threshold and ceiling define the dynamic range within which a procedure can detect changes in drug-induced receptor activation, and these constraints are different for different endpoints and associated procedures. For example, in this example, endpoint 1 has a lower threshold, higher ceiling, and wider dynamic range than endpoint 2. (C) Theoretical effect of agonist alone and agonist/antagonist (Ag/Antag) mixtures on endpoint 1 with threshold 1 and ceiling 1. (D) Theoretical effect of agonist alone and agonist/antagonist mixtures on endpoint 2 with threshold 2 and ceiling 2. (E) Plots relating agonist proportion in a mixture to maximal mixture effects (Emax) on a given endpoint, expressed as a percentage of the agonist-alone maximal effect on that endpoint. The lateral position of the plot can be defined by the EP50, which provides a measure of the efficacy requirement for the given endpoint and procedure. The slope of the plot provides a measure of the dynamic range between threshold and ceiling for the endpoint and procedure (steeper slopes imply narrower dynamic range).

Materials and Methods

In Vitro Studies

Chemicals.

[3H]Naloxone (70 Ci/mmol), [3H]rimonabant (SR141716A, 42 Ci/mmol), and [35S]GTPγS (1250 Ci/mmol) were purchased from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA). (−)-Naltrexone HCl; fentanyl HCl; CP55,940; rimonabant; WIN55,212-2; and [d-Ala2,N-MePhe4,Gly5-ol]enkephalin (DAMGO) were provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program (Bethesda, MD). All other chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) or Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Fentanyl, naltrexone, and DAMGO were dissolved in deionized H2O, whereas CP55,940; rimonabant; and WIN55,212-2 were dissolved in 95% ethanol.

Cell Culture and Membrane Preparation.

Cell lines used for this study were CHO cells stably transfected with either the mouse MOR (mMOR-CHO) expressing a [3H]naloxone maximum specific binding value of 2.70 ± 0.18 pmol/mg MOR (KD = 2.34 ± 0.34 nM) or mouse cannabinoid receptor 1 (mCB1R-CHO) expressing a [3H]rimonabant maximum specific binding value of 4.12 ± 0.63 pmol/mg CB1R (KD = 2.33± 0.34 nM). Cells were grown in a Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F12 medium containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 0.5% G418 for mMOR-CHO or 0.55% hygromycin B for mCB1R-CHO cells and cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. Cells were harvested by replacing media with cold phosphate-buffered saline followed by agitation and centrifuged at 1000g for 10 minutes. The resulting pellet was homogenized in membrane buffer (50 mM Tris, 3 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM EGTA, pH 7.4) and stored at −80°C until use. Cell homogenates were thawed, diluted, and homogenized in membrane buffer and then centrifuged at 50,000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The resulting pellet was homogenized in the indicated assay buffer prior to each assay. Protein was determined according to Bradford (1976).

Receptor Binding Assay.

Receptor competition binding assays were conducted both in the absence and in the presence of sodium and guanine nucleotides to determine high-affinity and low-affinity agonist binding Ki values, respectively. To determine binding under high-agonist-affinity conditions conventionally used to assess ligand affinities, mMOR-CHO (25–30 mg) or mCB1R-CHO (10–12 mg) cell membranes were incubated for 90 minutes at 30°C in assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 3 mM MgCl2, and 0.2 mM EGTA; pH 7.4) with 1.5 nM [3H]naloxone or 0.92 nM [3H]rimonabant, respectively, and varying concentrations of opioid (fentanyl or naltrexone) or cannabinoid (CP55,940 or rimonabant) ligands. Nonspecific binding was determined by inclusion of 5 mM naltrexone or 5 mM WIN55,212-2 for MOR and CB1R, respectively. Reactions were terminated by rapid filtration under vacuum through Whatman GF/B glass filter fibers, and the filters were then rinsed three times with ice-cold Tris-HCl (pH 7.7) buffer. Bound radioactivity was then determined by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry at 45% efficiency for 3H after 9-hour extraction of the filters in scintillation fluid. In the CB1R binding assays, 0.5% w/v bovine serum albumin (BSA) was included in the assay buffer, and the filters were soaked in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.7) buffer containing 0.5% BSA for at least 30 minutes prior to filtration. The same procedure was used to determine binding under low-agonist-affinity binding conditions, except that the assay buffer included 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM GDP, and 0.1 nM unlabeled GTPγS. Low-affinity binding conditions were used to mimic binding conditions in the functional assay of ligand-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding.

[35S]GTPγS Binding Assay.

mMOR-CHO (10 mg) or mCB1R-CHO (6 mg) cell membranes were incubated for 90 minutes at 30°C in assay buffer containing 100 mM NaCl, 20 µM GDP, 0.1 nM [35S]GTPγS, and varying concentrations of either a single drug (fentanyl, naltrexone, CP55,940, or rimonabant) or fixed-proportion mixtures of fentanyl/naltrexone or CP55,940/rimonabant. In the CB1R-CHO cell assays, 0.1% BSA was included in the assay buffer. Nonspecific binding was determined using 20 µM unlabeled GTPγS. Reactions were terminated by rapid vacuum filtration as described above. Bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry at 90% efficiency for 35S.

The fixed proportions of opioid (fentanyl/naltrexone) or cannabinoid (CP55,940/rimonabant) ligands in each mixture were based on their Ki values derived from competition binding in mMOR-CHO or mCB1R-CHO cell membranes, respectively, under low-agonist-affinity binding conditions to match the [35S]GTPγS binding conditions. Specifically, preliminary studies examined effects of an agonist/antagonist proportion for fentanyl/naltrexone and for CP55,940/rimonabant that was equal to the proportion of agonist and antagonist Ki values determined from the low-affinity competition binding studies. Based on these preliminary results, additional drug proportions were incremented up or down in approximately 0.25 or 0.5 log units with the intent of progressing from relatively high agonist-to-antagonist proportions that approached effects of the agonist alone to relatively low agonist-to-antagonist proportions that approached effects of the antagonist alone. The final mixture proportions expressed as X:1 agonist/antagonist were 965, 322, 107, 35.8, 11.9, and 3.97:1 for fentanyl/naltrexone and 128, 42.7, 14.2, 4.75, 1.59, and 0.526:1 for CP55,940/rimonabant.

In Vivo Studies

Drugs.

Fentanyl HCl; (−)-naltrexone HCl; CP55,940; and rimonabant were all provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program (Bethesda, MD). Fentanyl, naltrexone, and their mixtures were prepared in saline vehicle, whereas CP55,940; rimonabant; and their mixtures were prepared in a vehicle of 1:1:18 ethanol/emulphor/saline. Drug doses are expressed as the salt forms described above, and mixture proportions are adjusted for molecular weight. All drugs and mixtures were administered subcutaneously.

Subjects.

Adult male Swiss-Webster mice (Envigo Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were housed in groups of five in an American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited temperature- and humidity-controlled animal care facility with a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 6:00 AM). Mice had free access to food, water, and nesting material. On the day prior to experimentation, mice were moved to a testing room and allowed to acclimate overnight while remaining in their home cages. Each mouse was used only once. Animal maintenance and research adhered to guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (National Research Council, 2011) as adopted and promulgated by the National Institutes of Health. All animal use protocols were approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Warm Water Tail-Withdrawal Procedure.

A warm water tail-withdrawal procedure (Yuan et al., 2013) was used to evaluate treatment effects on tail-withdrawal latencies from water heated to 56 ± 0.2°C using a water bath (Thermo Scientific Precision). To determine tail-withdrawal latencies, each mouse was secured in a towel, the bottom 5 cm of the tail was immersed in the water bath, and the latency to tail withdrawal was recorded with a stop watch. A cutoff time of 10 seconds was used to prevent tissue damage during repeated testing. A group of 10 mice was used to study effects of each drug or mixture, and at the start of each experiment, baseline tail-withdrawal latencies were determined in each mouse before drug treatments. Only mice with baseline latencies of less than 5 seconds were used for subsequent drug testing. Seven of 130 mice failed to meet this criterion, so final group sizes for each drug or mixture ranged from 8 to 10 mice.

Once baseline tail-withdrawal latencies had been established, mice received a series of increasing subcutaneous doses of test drug or mixture administered in a cumulative-dosing procedure in which each dose increased the total dose by 0.25 or 0.5 log units. Tail-withdrawal latencies were determined 15 minutes after each dose and immediately before the next dose. Dose ranges were intended to go from low doses that had no effect on tail-withdrawal latencies to high doses that produced maximal effects in most mice, produced a plateau in tail-withdrawal latencies at a submaximal level, or reached the highest possible doses given drug solubility constraints. Raw tail-withdrawal latencies after each dose in each mouse were converted to percent maximal possible effect (%MPE) using the following equation:

|

To complement in vitro studies of ligand-stimulated [35S]GTPγS, in vivo behavioral studies were conducted with agonist/antagonist drug pairs acting either at MOR (fentanyl and naltrexone) or CB1R (CP55,940 and rimonabant). For each agonist/antagonist pair, effects were determined for the agonist and antagonist administered alone and for a series of fixed-proportion agonist/antagonist mixtures. Specifically, preliminary studies examined effects of an agonist/antagonist proportion for fentanyl/naltrexone and for CP55,940/rimonabant that produced approximately 50% of the agonist-alone Emax in the assay of ligand-modulated [35S]GTPγS binding. These mixtures produced full antinociception, so the agonist proportion was reduced in additional mixtures described above for the [35S]GTPγS studies. The final mixture proportions expressed as X:1 agonist/antagonist were 35.8, 11.9, 6.89, 3.97, and 1.37:1 for fentanyl/naltrexone and 5.56, 1.89, 0.625, and 0.213:1 for CP55,940/rimonabant.

Data Analysis

Analysis of In Vitro Data.

All samples were assayed in duplicate, and analysis was based on specific binding. Competition binding data were normalized as a percentage of radioligand bound in the absence of competing ligand. Competition curves (log inhibitor vs. response) were analyzed by four-parameter nonlinear regression, with the maximum binding constrained to 100% and minimum to 0%, to determine IC50 values and Hill coefficients. IC50 values were then converted to Ki values using the Cheng-Prussoff equation, where [L] is the concentration and KD is the equilibrium dissociation constant of the radioligand:

|

Ligand-modulated [35S]GTPγS binding data were normalized as a percentage of net-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding by a maximally effective concentration of a standard full agonist at each receptor: DAMGO for MOR and WIN55,212-2 for CB1R, where net-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding was defined as binding in the presence of ligand minus that in the absence of ligand (basal). Concentration-effect curves (log agonist vs. response) were analyzed by four-parameter nonlinear regression, with the minimum constrained to 0, to obtain Emax and log EC50 values. For the inverse agonist rimonabant and mixtures inhibiting [35S]GTPγS binding, the maximum was constrained to 0, and Emax values were obtained as the minimum. Statistical significance of differences between Ki, Emax, or log EC50 values were determined using the two-tailed Student’s t test when comparing two values or with ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test when comparing more than two values. Hill coefficients were compared with a value of one using a one-sample Student’s t test. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Curve-fitting and statistical analyses for in vitro data and all other analyses described below were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 8.4.3 software.

Analysis of In Vivo Data.

%MPE values were averaged across mice to yield mean ± S.E.M. values for each dose of each drug or mixture. For each agonist alone, an ED50 value (95% confidence limits) was defined as the dose producing 50% MPE and was determined using four-parameter nonlinear regression of dose-effect curves with the minimum constrained to 0 and the maximum constrained to the %MPE obtained at the highest drug dose tested. This was necessary because dose-effect curves of several of the CP55,940/rimonabant mixtures did not contain a sufficient number of points on the maximum plateau. Further, solubility limits with the cannabinoid mixtures prevented achievement of a maximum plateau.

Analysis for Comparison of In Vitro and In Vivo Effects.

For each mixture in each assay, maximum mixture effects were expressed as the percentage of the maximum effect produced by the agonist alone relative to the antagonist alone using the following equation:

|

where Mixture, Agonist, and Antagonist equal the maximal effect on a given endpoint for the mixture, agonist alone, and antagonist alone, respectively. %Agonist Maximum values were plotted as a function of agonist proportion in the mixture (pAgonist), and the resulting pAgonist − %Agonist Maximum curve was then evaluated by nonlinear regression with the maximum constrained to 100% and the minimum constrained to 0% to determine two parameters. First, the EP50 was defined as the effective agonist proportion producing 50% Agonist Maximum effect, and this provided a measure of the efficacy requirement for the designated endpoint. Second, the slope of the curve (provided by the Hill coefficient) was determined to provide a measure of the dynamic range of the designated endpoint for detecting agonist effects. EP50 and slope values for in vitro and in vivo effects were considered to be significantly different if 95% confidence limits did not overlap.

Results

In Vitro Studies

Receptor Binding.

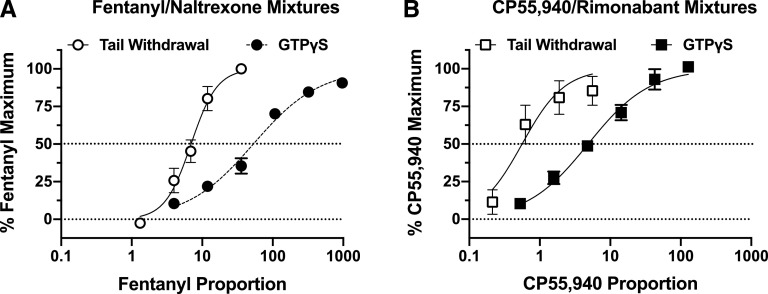

Figure 2 and Table 1 show data for receptor binding studies. In mMOR-CHO cells, both fentanyl and naltrexone competed with high affinity for [3H]naloxone binding to the MOR in the absence of sodium and guanine nucleotides (high-agonist-affinity state), with low to subnanomolar Ki values that were not significantly different from each other. However, in the presence of sodium and guanine nucleotides (low-agonist-affinity state), the MOR affinity of fentanyl was significantly decreased (by ∼81-fold), whereas that of naltrexone was not significantly altered. The Hill coefficient of fentanyl binding was significantly less than one in the absence of sodium and guanine nucleotides but did not differ from one in their presence; Hill coefficients of naltrexone binding did not differ from one regardless of assay conditions. The ratio of low-affinity fentanyl to naltrexone Ki values was 322.

Fig. 2.

Competition binding in the absence and presence of sodium and guanine nucleotides in membranes from mMOR-CHO and mCB1R-CHO cells. mMOR-CHO (A) or mCB1R-CHO (B) membranes were incubated with [3H]naloxone (A) or [3H]rimonabant (B) and varying concentrations of the indicated agonist (fentanyl, CP55,940) or antagonist (naltrexone, rimonabant) ligands in the absence or presence of sodium (Na+ from 100 mM NaCl) and guanine nucleotides (GN; 20 µM GDP and 0.1 µM GTPγS). Data are mean values ± S.E.M. (n = 5–8). Specific [3H]naloxone binding in the absence of competitor was 1.22 ± 0.10 and 0.65 ± 0.13 pmol/mg in mMOR-CHO cells in the absence and presence of sodium and guanine nucleotides, respectively. Specific [3H]rimonabant binding in the absence of competitor was 2.54 ± 0.35 and 3.00 ± 0.53 pmol/mg in mCB1R-CHO cells in the absence and presence of sodium and guanine nucleotides, respectively. Agonist but not antagonist competition curves were right-shifted by sodium and guanine nucleotides, with fentanyl binding affected to a greater extent than CP55,940 binding.

TABLE 1.

Receptor competition binding values without and with sodium and guanine nucleotides

Values are means ± S.E.M. from the competition binding curves shown in Fig. 2. Na+, 100 mM NaCl; GN, guanine nucleotides (20 µM GDP and 0.1 nM GTPγS).

| No Na+, No GN | With Na+ and GN | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor; Ligand | Ki | nH | Ki | nH |

| nM | nM | |||

| MOR; fentanyl | 1.51 ± 0.09 | 1.04 ± 0.02 | 122.6 ± 20.9*** | 0.76 ± 0.08** |

| MOR; naltrexone | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 1.03 ± 0.04 | 0.38 ± 0.06* | 1.12 ± 0.12 |

| CB1R; CP55,940 | 25.3 ± 3.7 | 0.76 ± 0.06 | 71.6 ± 11.8** | 0.84 ± 0.04 |

| CB1R; rimonabant | 0.82 ± 0.12 | 1.28 ± 0.06 | 0.56 ± 0.08 | 1.18 ± 0.17 |

P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 different from No Na+, No GN condition by Student’s t test.

In mCB1R-CHO cells, CP55,940 competed with [3H]rimonabant binding to the CB1R with relatively high affinity (Ki ∼25 nM) in the absence of sodium and guanine nucleotides, whereas rimonabant had higher CB1R affinity with a subnanomolar Ki value. In the presence of sodium and guanine nucleotides, the CB1R affinity of CP55,940 was significantly decreased (by ∼2.8-fold), whereas that of rimonabant was not altered. The Hill coefficient of CP55,940 binding was significantly less than one in the absence of sodium and guanine nucleotides but not in their presence, whereas the Hill coefficient for rimonabant binding was not different from one under either assay condition. The ratio of low-affinity CP55,940 to rimonabant Ki values was 128.

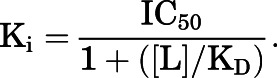

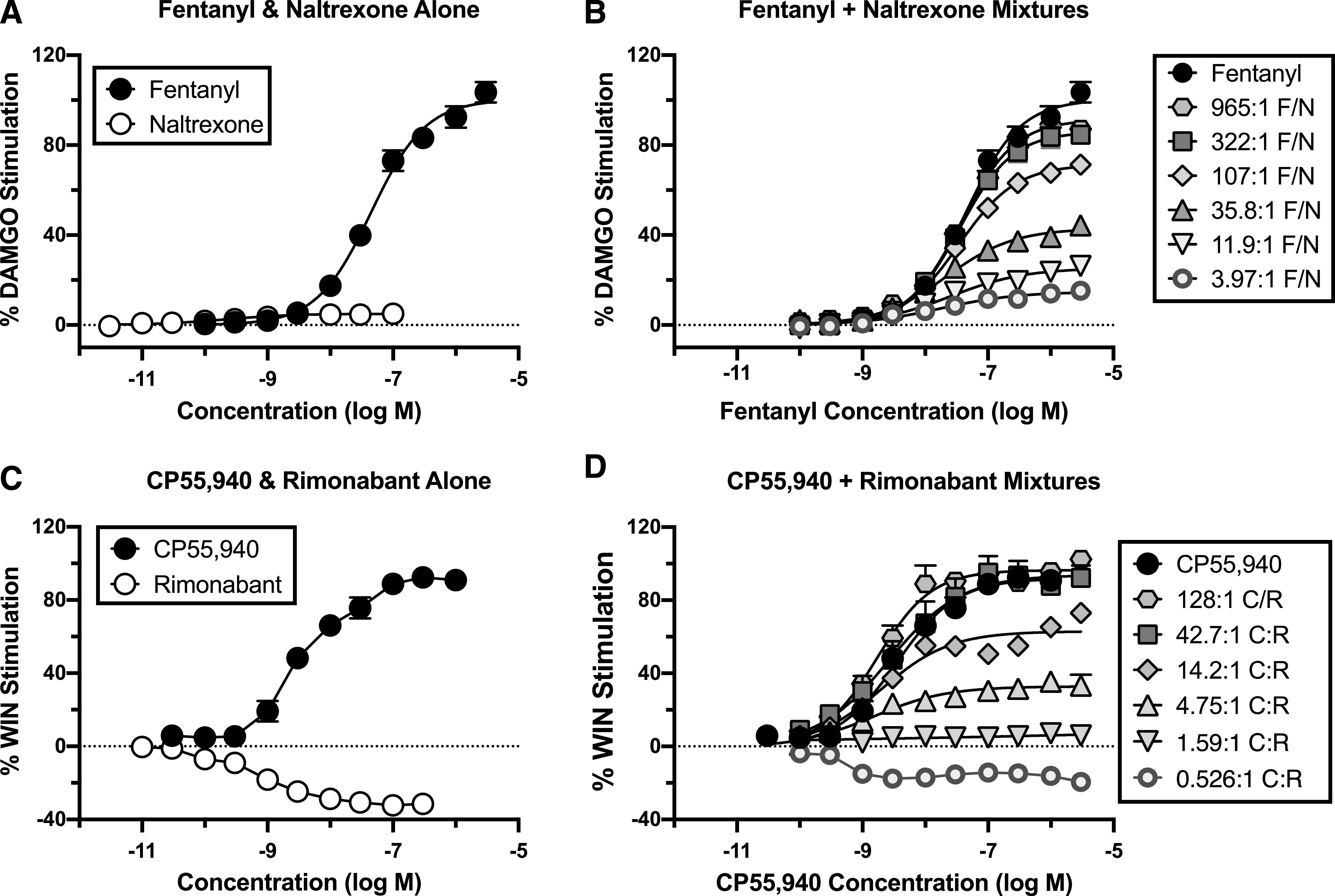

Ligand-Stimulated [35S]GTPγS Binding.

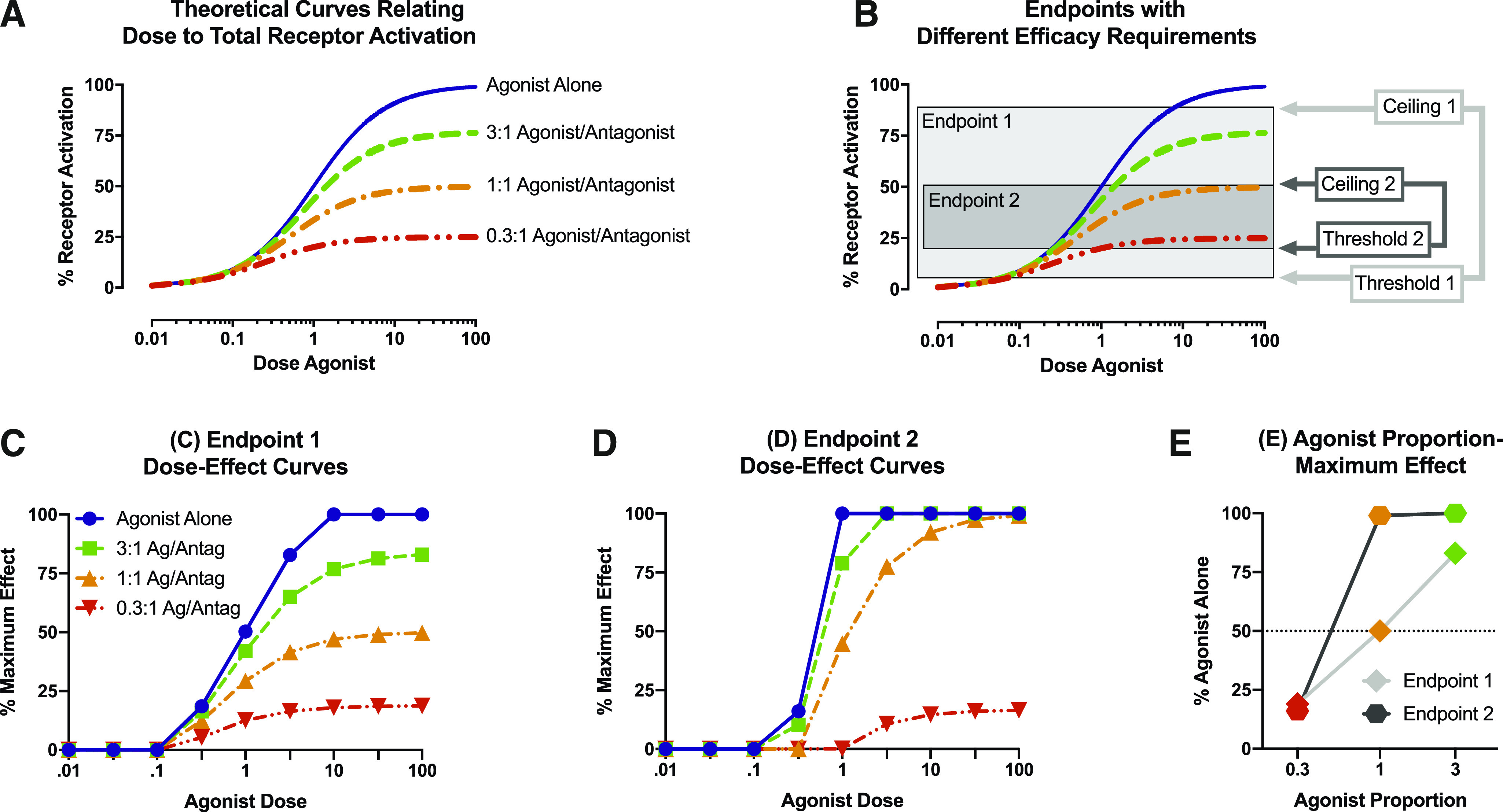

Figure 3 and Table 2 show results from studies of ligand-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding. In studies with mMOR-CHO cells, fentanyl alone acted as full agonist with Emax = 100.1% ± 3.3% relative to the reference agonist DAMGO, whereas naltrexone produced only minimal activation (Emax = 5.2% ± 0.3%). Increasing proportions of fentanyl in the mixtures produced graded increases in Emax values. The mixture with the lowest fentanyl proportion (3.97:1 F/N) had an Emax value of 15.0% ± 1.2% that was not significantly different from that of naltrexone alone, and the mixture with the highest fentanyl proportion (965:1) had an Emax (91.3% ± 0.8%) that was not significantly different from fentanyl alone. In contrast to Emax values, log EC50 values were generally unaffected by the proportion of fentanyl in the mixture. Thus, the log EC50 value of fentanyl alone was −7.35 ± 0.01 (44.6 nM), and although there was a slight trend toward increasing potency as the proportion of fentanyl decreased, no mixture log EC50 value differed from that of fentanyl alone except for the mixture with the lowest fentanyl proportion (3.97:1 F/N; log EC50 = −7.72 ± 0.11; ∼22 nM). This mixture also produced the only concentration-effect curve with a Hill coefficient (0.72 ± 0.05) that significantly differed from one. The naltrexone EC50 value (−9.56 ± 0.10; ∼0.3 nM) was significantly lower than that of fentanyl alone and all mixtures.

Fig. 3.

Effects of fixed-proportion agonist/antagonist mixtures on ligand-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in membranes from mMOR-CHO and mCB1R-CHO cells. mMOR-CHO (A and B) or mCB1R-CHO (C and D) membranes were incubated with 20 µM GDP and 0.1 nM [35S]GTPγS and varying concentrations of fentanyl or naltrexone alone (A); CP55,940 or rimonabant alone (C); or the indicated fixed proportions of fentanyl/naltrexone (B) or CP55,940/rimonabant (D). The x-axes in (A and C) show the concentration of either the agonist or the antagonist administered alone. The x-axes of (B and D) show the concentration of the agonist only, and the antagonist concentration can be calculated as agonist concentration ÷ fixed-proportion dose ratio of agonist to antagonist. Fixed-proportion concentration ratios are expressed as X:1 agonist/antagonist, which are fentanyl/naltrexone (F/N) in mMOR-CHO and CP55,940/rimonabant (C/R) in mCB1R-CHO cells. Data represent percentage of the stimulation produced by a maximally effective concentration (3 µM) of a full agonist at each receptor type: DAMGO for MOR (A and B) and WIN55,212-2 (WIN) for CB1R (C and D). All values are means ± S.E.M. (n = 3–6). Basal and net DAMGO-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in mMOR-CHO cells was 50.2 ± 3.4 fmol/mg and 186.3 ± 15.5 fmol/mg, respectively (n = 16). Basal and net CP55,940-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in mCB1R-CHO cells was 107.4 ± 7.0 and 190.6 ± 11.2 fmol/mg, respectively (n = 25). Fixed-proportion mixtures generally showed increasing maximal stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding as a function of increasing proportion of agonist to antagonist. Rimonabant alone and the 0.526:1 CP55,940/rimonabant mixture reduced [35S]GTPγS binding below basal levels consistent with inverse agonism.

TABLE 2.

Emax and EC50 values of fixed-proportion agonist/antagonist mixtures in ligand-modulated [35S]GTPγS binding

Emax, EC50, and Hill coefficient values are derived from the concentration-effect curves shown in Fig. 3. Fixed-proportion concentration ratios are expressed as X:1 agonist/antagonist, which are fentanyl/naltrexone (F/N) in MOR-expressing cells and CP55,940/rimonabant (C/R) in CB1R-expressing cells. Emax values are expressed as a percentage of the stimulation produced by a maximally effective concentration (%Max) of a full agonist at each receptor type (DAMGO for MOR and WIN55,212-2 for CB1R). EC50 values for agonist alone and all mixtures are expressed as log M agonist concentration along with conversion to [nanomolar] concentration, whereas EC50 values listed for each antagonist alone represent the log M EC50 [nanomolar] concentration of the antagonist. For mixtures, the antagonist concentration at the EC50 value can be calculated as EC50 ÷ fixed-proportion dose ratio of agonist to antagonist. All values are means ± S.E.M. (MOR n = 4; CB1 n = 3–6). Emax or log EC50 values without any overlapping letter designations (within each receptor type) are P < 0.05 different from each other by ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

| Receptor | Mixture | Emax (%Max) | EC50 (log M) | Hill Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nM | ||||

| MOR | Fentanyl | 100.1 ± 3.3a | −7.35 ± 0.01a [44.6] | 1.00 ± 0.03 |

| MOR | 965 F:1 N | 91.3 ± 0.8ab | −7.42 ± 0.05ab [39.4] | 0.98 ± 0.03 |

| MOR | 322 F:1 N | 85.5 ± 2.8b | −7.45 ± 0.02ab [35.5] | 1.01 ± 0.03 |

| MOR | 107 F:1 N | 71.7 ± 1.6c | −7.46 ± 0.03ab [35.4] | 0.96 ± 0.06 |

| MOR | 35.8 F:1 N | 38.7 ± 4.2d | −7.61 ± 0.07ab [25.6] | 0.82 ± 0.06 |

| MOR | 11.9 F:1 N | 25.8 ± 2.5de | −7.57 ± 0.04ab [27.6] | 0.77 ± 0.11 |

| MOR | 3.97 F:1 N | 15.0 ± 1.2ef | −7.72 ± 0.11b [21.9] | 0.72 ± 0.05a |

| MOR | Naltrexone | 5.2 ± 0.3f | −9.56 ± 0.10c [0.29] | 0.83 ± 0.11 |

| CB1R | CP55,940 | 93.3 ± 5.1a | −8.48 ± 0.05a [3.44] | 0.99 ± 0.10 |

| CB1R | 128 C:1 R | 97.0 ± 1.0a | −8.73 ± 0.11a [2.24] | 1.00 ± 0.09 |

| CB1R | 42.7 C:1 R | 90.9 ± 5.9a | −8.61 ± 0.17a [3.76] | 0.88 ± 0.04 |

| CB1R | 14.2 C:1 R | 62.6 ± 3.1b | −8.72 ± 0.11a [2.23] | 0.96 ± 0.09 |

| CB1R | 4.75 C:1 R | 33.2 ± 2.5c | −8.85 ± 0.17a [2.16] | 1.11 ± 0.22 |

| CB1R | 1.59 C:1 R | 8.1 ± 1.0d | −9.20 ± 0.36a [1.76] | 0.69 ± 0.15 |

| CB1R | 0.526 C:1 R | −16.1 ± 3.4e | −10.3 ± 0.22b [0.09] | 2.29 ± 0.49 |

| CB1R | Rimonabant | −31.5 ± 2.2e | −9.20 ± 0.10a [0.72] | 0.89 ± 0.11 |

aa-e Emax or log EC50 values without any overlapping letter designations (within each receptor type) are P < 0.05 different from each other by ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. aHill coefficient is P < 0.05 different from one by Student’s t test.

In studies with mCB1R-CHO cells, CP55,940 acted as a full agonist with Emax = 93.3% ± 5.1% relative to the reference agonist WIN55,212-2, whereas rimonabant acted as an inverse agonist that reduced activity below the basal level (Emax = −31.5% ± 2.25%). The Emax values of the mixtures increased as the proportion of CP55,940 in the mixture increased. The mixture with the lowest CP55,940 proportion (0.526:1 C/R) produced a negative Emax value similar to rimonabant alone, whereas the mixtures with the highest CP55,940 proportions (128:1 or 42.6:1 C/R) had Emax values that were not different from CP55,940 alone. In contrast to Emax values, log EC50 values generally did not differ between CP55,940, rimonabant, and the various mixtures, except for 0.526:1 C/R, which inhibited [35S]GTPγS binding with higher potency than all other treatments. Hill slopes did not differ significantly from one; however, variability in the Hill slope of the 0.526:1 C/R mixture might have caused an artifactually high potency.

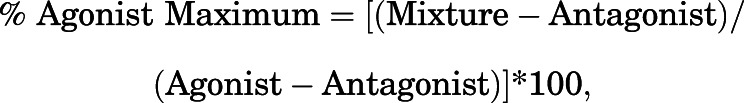

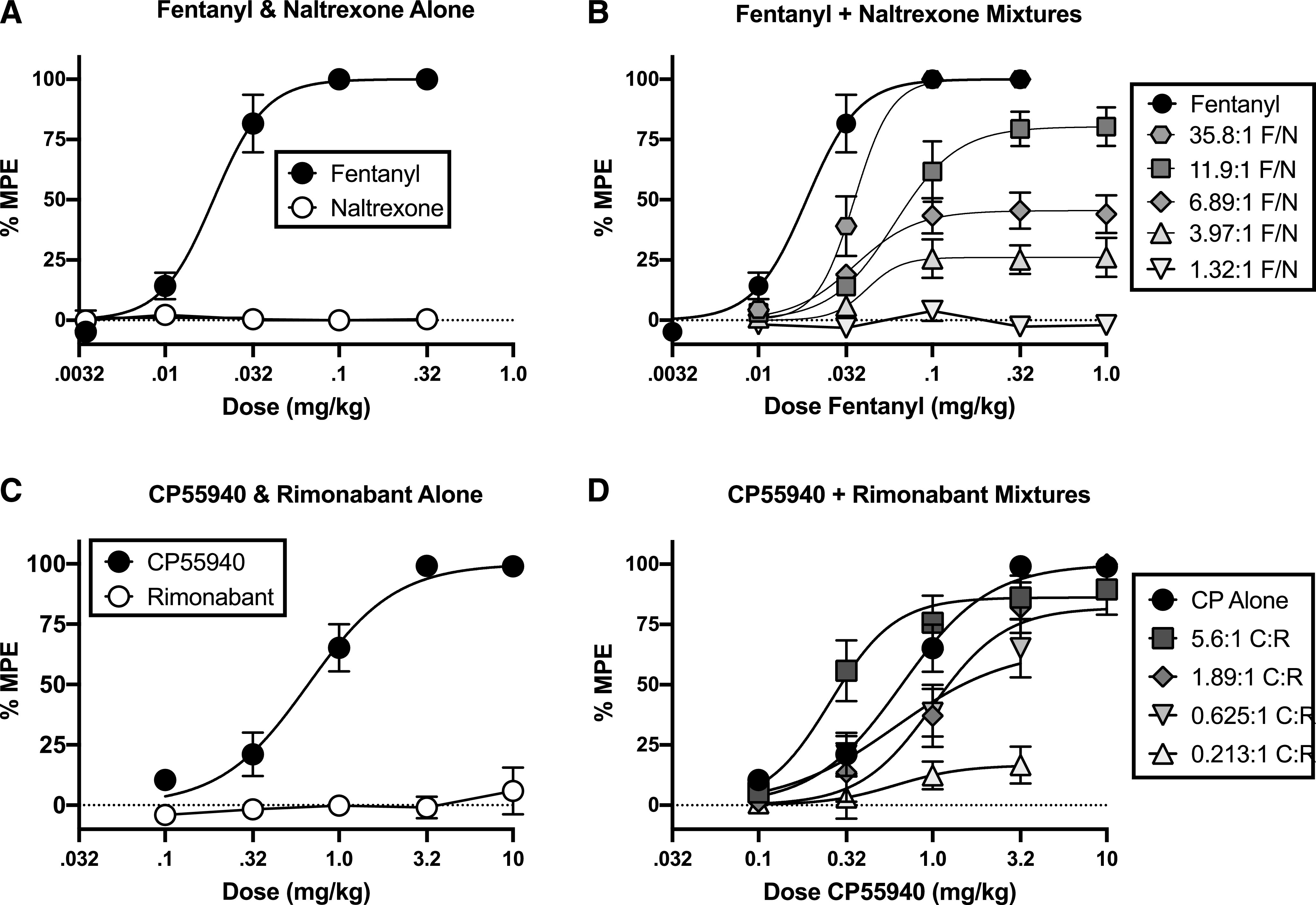

In Vivo Studies

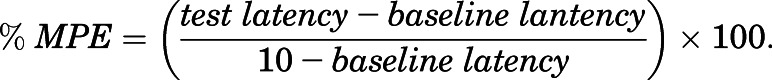

Figure 4 and Table 3 show results from studies of warm water tail withdrawal in mice. Mean ± S.E.M. baseline tail-withdrawal latencies ranged from 1.44 ± 0.10 to 3.99 ± 0.22 seconds across groups and averaged 2.83 ± 0.12 seconds for all mice in the study. Administration of fentanyl alone produced dose-dependent antinociception to a maximum effect of 100% MPE, whereas naltrexone alone had no effect. Fixed-proportion mixtures of fentanyl and naltrexone produced increasing maximum effects as the proportion of fentanyl in the mixture increased. Similarly, the CB1R agonist CP55,940 produced dose-dependent antinociception to a maximum effect of 100% MPE, whereas rimonabant had no effect when administered alone. In assessment of fixed-proportion mixtures of CP55,940 and rimonabant, constraints on solubility prevented assessment of high mixture doses sufficient to identify plateaus in mixture effects as with the fentanyl/naltrexone mixtures. However, for the doses that could be examined, fixed-proportion mixtures of CP55,940 and rimonabant produced increasing maximum effects as the proportion of CP55,940 in the mixture increased. Although there were some differences in ED50 values across agonists alone and agonist/antagonist mixtures, these differences did not vary as a systematic function of agonist proportion in the mixtures.

Fig. 4.

In vivo effects of fixed-proportion agonist/antagonist mixtures in a warm water tail-withdrawal assay of thermal nociception in mice. Mice were injected with varying doses of fentanyl or naltrexone alone (A); CP55,940 or rimonabant alone (C); or the indicated fixed-proportion mixtures of fentanyl + naltrexone (B) or CP55,940 + rimonabant (D). The x-axes in (A and C) show dose of either the agonist or the antagonist administered alone. The x-axes of (B and D) show the dose of the agonist only, and the antagonist dose can be calculated as agonist dose ÷ fixed-proportion dose ratio of agonist to antagonist. Fixed-proportion dose ratios are expressed as X:1 agonist/antagonist, which are fentanyl/naltrexone (F/N) and CP55,940/rimonabant (C/R). Data represent %MPE with a 10-second cutoff in 56°C water. All values are means ± S.E.M. (n = 8–10). Fixed-proportion mixtures generally showed increasing antinociception as a function of increasing agonist proportion in the mixtures.

TABLE 3.

Emax and ED50 values of fixed-proportion agonist/antagonist mixtures in the warm water tail-withdrawal assay of thermal antinociception in mice

Emax, ED50, and Hill coefficient values are derived from the dose-response curves shown in Fig. 4. Fixed-proportion dose ratios are expressed as X:1 agonist/antagonist, which are fentanyl/naltrexone (F/N) and CP55,940/rimonabant (C/R). Emax values are expressed as %MPE. ED50 values are expressed as agonist dose in micrograms per kilogram. For mixtures, the antagonist concentration at the ED50 value can be calculated as ED50 ÷ fixed-proportion dose ratio of agonist to antagonist. All values are means (95% confidence limits) (n = 8–10). Values without any overlap in confidence limits are P < 0.05 different from each other, although upper or both confidence limits of some values could not be accurately determined.

| Receptor | Mixture | Emax (%MPE) | ED50 | Hill Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| µg/kg | ||||

| MOR | Fentanyl | 100 | 20.2 (15.2–23.7) | 2.90 (2.03–4.67) |

| MOR | 35.8 F:1 N | 100 | 35.6 (31.2–43.5) | 4.06 (1.97–∞) |

| MOR | 11.9 F:1 N | 80.3 (61.8–98.8) | 60.7 (43.7–83.3) | 2.40 (1.37–∞) |

| MOR | 6.89 F:1 N | 45.5 (28.2–62.8) | 35.8 (22.1–56.2) | 2.45 (1.03–∞) |

| MOR | 3.97 F:1 N | 26.1 (7.31–44.8) | 42.2 (21.8–∞) | 5.67 (0.54–∞) |

| MOR | 1.32 F:1 N | −2.09 (−5.08 to 0.89) | N.D. | N.D. |

| MOR | Naltrexone | 0.42 (−2.08 to 2.91) | N.D. | N.D. |

| CB1R | CP55,940 | 100 | 665 (518–845) | 1.73 (1.22–2.58) |

| CB1R | 5.56 C:1 R | 86.2 (65.6–106.8) | 259 (174–395) | 2.35 (1.08–∞) |

| CB1R | 1.89 C:1 R | 82.0 (58.3–105.7) | 997 (589–1556) | 2.09 (0.97–∞) |

| CB1R | 0.625 C:1 R | 65.2 (37.8–92.6) | 614 (317–1137) | 1.34 (0.67–3.17) |

| CB1R | 0.213 C:1 R | 16.6 (−0.68 to 33.9) | 612 (N.D.) | 2.22 (−0.03 to ∞) |

| CB1R | Rimonabant | 5.9 (−15.9 to 23.8) | N.D. | N.D. |

N.D., values could not be determined.

Comparison of In Vitro and In Vivo Effects

The maximum effects of each mixture were expressed as a percentage of the maximum effect of the constituent agonist alone (percent agonist-alone Emax) and plotted as a function of the agonist proportion in the mixture (pAgonist). These pAgonist-Emax plots are shown in Fig. 5. For fentanyl/naltrexone mixtures, increasing agonist proportions produced increasing maximal effects on both in vitro ligand-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding and in vivo antinociception. Table 4 shows that the EP50 value (i.e., effective agonist proportion to produce an Emax that is 50% of agonist-alone Emax) was significantly lower for antinociception, indicating that antinociception had a lower efficacy requirement than ligand-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding. Table 4 also shows that the slope was steeper for antinociception, indicating that antinociception had a narrower dynamic range for detection of agonist effects than [35S]GTPγS binding.

Fig. 5.

Effect of agonist proportion on the maximal effect produced by fixed-proportion agonist/antagonist mixtures. Maximum mixture effects from in vitro studies of ligand-modulated [35S]GTPγS binding and in vivo studies of thermal antinociception are expressed as percent maximum effect of fentanyl vs. naltrexone alone (A) or CP55,940 vs. rimonabant alone (B) on the ordinate and plotted as a function of the agonist vs. antagonist proportion in each mixture on the abscissa. All values are means ± S.E.M. (n = 3–5 for GTPγS and 8–10 for warm water tail withdrawal). Percent agonist-alone values for each measure increased as a function of the proportion of agonist in each mixture. Table 4 shows EP50 and slope parameters derived from these curves.

TABLE 4.

EP50 and Hill coefficient values from plots of agonist proportion vs. maximal effect for data from the in vitro assay of ligand-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding and in vivo assay of warm water tail withdrawal or drug discrimination

EP50 and Hill coefficient values are derived from the proportion-maximal effect curves shown in Fig. 5. The EP50 value is defined as the X:1 agonist/antagonist concentration ratio at which 50% of the theoretical maximal response of agonist alone compared with antagonist alone was achieved in each measure. All values are means with confidence limits (tail withdrawal n = 8–10; GTPγS n = 3–5). EP50 and Hill coefficient values are considered significantly different from each other when there is no overlap between confidence limits.

| Receptor | Measure | EP50 | Hill Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOR | [35S]GTPγS | 53.01 (43.28–63.40) | 0.92 (0.79–1.09) |

| MOR | TW-56°C mouse | 6.94 (5.95–8.08) | 2.35 (1.67–3.39) |

| MORa | DD-rat | 3.69 (2.07–5.93) | 1.85 (0.15–16.85) |

| MORa | TW-50°C monkey | 8.98 (5.42–14.82) | 2.39 (0.88–∞) |

| MORa | TW-50°C rat | 13.90 (12.27–15.66) | 2.05 (1.27–6.89) |

| MORa | TW-54°C monkey | 14.14 (8.72–21.36) | 1.93 (0.90–∞) |

| CB1R | [35S]GTPγS | 4.85 (3.79–6.14) | 1.00 (0.81–1.24) |

| CB1R | TW-56°C mouse | 0.56 (0.35–0.94) | 1.45 (0.69–∞) |

DD, drug discrimination; TW, tail withdrawal.

For the CP55,940/rimonabant mixtures, EP50 values for in vivo antinociception should be considered estimates because constraints in solubility prevented determination of effect plateaus for some mixtures. As a result, maximal effects for those mixtures may be underestimated, and the actual position of the curve relating agonist proportion to percent maximal agonist effect may be located to the left of that shown in the figure. Given this caveat, increasing CP55,940 proportions produced increasing maximal effects on both in vitro and in vivo endpoints. Table 4 shows that the EP50 value was significantly lower for antinociception, indicating that for cannabinoids as for opioids, antinociception had a lower efficacy requirement than ligand-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding. Table 4 also shows that slopes were not different, indicating that both endpoints had a similar dynamic range of sensitivity to agonist effects.

Discussion

This study evaluated the utility of fixed-proportion agonist/antagonist mixtures to manipulate pharmacodynamic efficacy and to probe efficacy requirements for MOR- and CB1R-mediated effects. There were three main findings. First, consistent with predictions of receptor theory and with previous results using other species and endpoints, increasing fentanyl proportions in a series of fentanyl/naltrexone mixtures produced increasing maximal effects for both an in vitro and an in vivo measure of MOR-mediated drug effects. Second, this general pattern of results with an MOR agonist/antagonist pair was extended to the CB1R agonist/antagonist pair of CP55,940 and rimonabant, providing evidence for generalization of this finding to another receptor type. Lastly, the agonist proportion in agonist/antagonist mixtures may serve not only as a useful variable for manipulating net efficacy but also as a useful scale for quantifying the efficacy requirement and dynamic range of different effects mediated by a common receptor type. In this case, results suggest that in vitro ligand-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in CHO cells had a higher efficacy requirement than in vivo antinociception for both MOR and CB1R activation.

Fentanyl/Naltrexone Mixtures.

The present results agree with our previous finding that fixed-proportion fentanyl/naltrexone mixtures produce graded and increasing maximum effects as the fentanyl proportion in the mixtures increases (Cornelissen et al., 2018; Schwienteck et al., 2019). Our previous studies examined fentanyl/naltrexone mixture effects on in vivo behavioral endpoints in rhesus monkeys and rats and directly compared effects of fentanyl/naltrexone mixtures to effects of different MOR ligands that vary in efficacy. The present study extended these findings in two ways. First, this study used an in vitro assay of ligand-modulated [35S]GTPγS binding in mMOR-CHO cells to compare mixture efficacies to activate the initial step of MOR signaling. Assays of [35S]GTPγS binding have an established history of use for comparing the efficacies of MOR ligands (Traynor and Nahorski, 1995; Emmerson et al., 1996; Selley et al., 1997; Selley et al., 1998). Accordingly, this procedure provided an important test of the hypothesis that agonist proportion in fixed-proportion agonist/antagonist mixtures could be systematically manipulated to control net efficacy of the mixture. Our results support this hypothesis. Concentration-effect curves for each fentanyl/naltrexone mixture produced concentration-dependent increases in [35S]GTPγS binding up to a plateau, and Emax values increased as the fentanyl proportion in the mixture increased. These results also illustrate the principle that agonist/antagonist mixture efficacy can be precisely controlled by titrating the agonist proportion.

Although maximal levels of [35S]GTPγS binding can vary either across individual MOR ligands or across agonist/antagonist mixtures, it should be noted that this qualitative similarity is mediated by distinct mechanisms. For individual drugs, increasing concentrations will eventually produce full receptor occupancy, and differences in maximal receptor activation across drugs reflect differences in efficacy to activate each receptor. For agonist/antagonist mixtures, the efficacies of the agonist and antagonist at the receptor do not change across mixtures, but the agonist proportion in the mixture determines maximal receptor occupancy by the agonist. Thus, differences in maximal receptor activation across mixtures reflect differences in maximal receptor occupation by the agonist.

A theoretically important proportion for research with agonist/antagonist mixtures is when the ratio of agonist to antagonist concentrations in the mixture is equal to the ratio of agonist to antagonist affinities at the receptor. At this proportion, high mixture concentrations should produce 50% receptor occupancy by the agonist and 50% by the antagonist. In the absence of any receptor reserve, this agonist/antagonist proportion should produce a maximum effect that is halfway between the agonist- and antagonist-alone maximal effects, i.e., the EP50 value. Receptor reserve is implied for a given endpoint if the EP50 for that endpoint is less than the ratio of agonist to antagonist affinities. Because of the special implications for this proportion, the present study determined fentanyl and naltrexone affinities at MOR in competition binding assays. Using conventional high-affinity assay conditions, fentanyl and naltrexone affinities were similar to previously reported values (Emmerson et al., 1994; Emmerson et al., 1996), and the ratio of fentanyl Ki to naltrexone Ki was 7.19. However, affinities were also determined using low-affinity binding conditions that matched conditions in the functional assay of [35S]GTPγS binding. These low-affinity binding conditions produced greater decreases in affinity for the agonist fentanyl than for the antagonist naltrexone as previously described for these and other MOR ligands (Childers, 1991; Emmerson et al., 1994; Emmerson et al., 1996). As a result, the ratio of fentanyl Ki to naltrexone Ki under low-affinity conditions increased to 322, and this was included as the initial ratio of fentanyl to naltrexone for studies of [35S]GTPγS binding. This mixture produced a maximal effect nearly as high as fentanyl alone, and as a result, only one higher fentanyl proportion was studied along with a series of lower fentanyl proportions until mixtures were identified that produced effects similar to naltrexone alone. Overall, the EP50 for fentanyl/naltrexone mixtures to stimulate [35S]GTPγS binding in mMOR-CHO cells was approximately 6-fold lower than the ratio of fentanyl to naltrexone low-affinity Ki values. As noted above, the finding that the EP50 was lower than the ratio of agonist to antagonist Ki values suggests the existence of receptor reserve, which agrees with earlier results comparing low-affinity binding Ki values with EC50 values for stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding in mMOR-CHO cells by fentanyl and other high-efficacy MOR ligands (Selley et al., 1998).

The present study also extended evaluation of fentanyl/naltrexone mixtures to thermal antinociception in mice. The EP50 value was lower and the slope steeper for mixture effects in this behavioral assay than in the in vitro assay. The lower EP50 value indicates that this assay of thermal antinociception in mice has an even lower efficacy requirement (and higher receptor reserve) than the assay of ligand-modulated [35S]GTPγS binding. Moreover, the steeper slope indicates that thermal antinociception has a narrower dynamic range than ligand-modulated [35S]GTPγS binding. Accordingly, the assays of thermal antinociception and [35S]GTPγS binding can be conceptualized as having relative threshold and ceiling values similar to endpoints 1 and 2, respectively, in Fig. 1.

This comparison of fentanyl/naltrexone mixture effects across assays also illustrates the general principle that curves relating agonist proportion to percent agonist-alone effect can be directly compared across endpoints that can span cellular to behavioral levels of analysis in any species and permit quantitative estimates of efficacy requirements. For example, Table 4 compares the EP50 and slope values for fentanyl/naltrexone mixtures in assays of ligand-modulated [35S]GTPγS binding and thermal antinociception in mice (present study) with those in assays of fentanyl discrimination in rats and thermal antinociception determined previously in rats and rhesus monkeys (Cornelissen et al., 2018; Schwienteck et al., 2019). The fentanyl discrimination procedure in rats had the lowest EP50 value, followed by thermal antinociception in mice (56°C) ≤ monkeys (50°C) ≤ rats (50°C) ≅ monkeys (54°C). Moreover, EP50 values for all of these behavioral effects were lower than the EP50 value for in vitro stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding. Slopes generally had large confidence limits, but in general, behavioral endpoints had similar steep slope values in comparison with the shallower slope for [35S]GTPγS binding.

As a final theoretical point, we would note that the approach used here embraces the reality that all assays have constraints on both their sensitivity and capacity to detect drug effects. This is perhaps most obvious in behavioral assays. As one example, many assays of thermal nociception such as the one used here include a cutoff time to protect subjects from excessive exposure to the noxious stimulus, but this cutoff imposes a somewhat arbitrary ceiling on drug effects that may obscure true differences in drug efficacies. However, these constraints also operate in vitro. For example, the assay of agonist-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in membranes from mMOR-CHO cells used here also has a ceiling imposed by factors including the stoichiometry of receptors to G-proteins and the concentration of [35S]GTPγS and GDP (Selley et al., 1997; Breivogel et al., 1998). Because of this ceiling, some drugs (e.g., fentanyl and methadone) have similar Emax values despite having demonstrably different Emax values for the same endpoint of agonist-stimulated GTPγS binding in other membranes (e.g., rat thalamus membranes with lower receptor density). Overall, we would argue that this assay dependence of Emax measurement is precisely why quantitative efficacy measurements are so challenging. One value of plots relating agonist proportion to Emax values, such as those shown in Fig. 1E and Fig. 5, is that they provide a tool for directly comparing and quantifying the relative threshold and ceiling values across endpoints.

CP55,940/Rimonabant Mixtures.

Effects of CP55,940/rimonabant mixtures paralleled those of fentanyl/naltrexone mixtures in several major respects that included 1) increasing maximal effects with increasing agonist proportions; 2) EP50 values lower than agonist-to-antagonist low-affinity Ki ratio, indicating receptor reserve on both endpoints; and 3) an EP50 for in vivo thermal antinociception that was significantly lower than that for in vitro stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding. These results suggest that fixed-proportion agonist/antagonist mixtures may have general utility both to control efficacy of pharmacological stimulation at a given receptor type and to scale the relative efficacy requirements for different effects mediated by that receptor.

In addition to these similarities across opioid and cannabinoid agonist/antagonist mixtures, there were also notable differences. First, in agreement with some previous findings (Bouaboula et al., 1997; Landsman et al., 1997), rimonabant functioned as an inverse agonist in the assay of ligand-modulated [35S]GTPγS binding, suggesting the existence of constitutive CB1R activity in mCB1R-CHO cells. Nonetheless, mixtures still produced graded Emax values between those of rimonabant and CP55,940 alone. As such, these results suggest that mixtures may be useful to control levels of inverse agonist activity as well as agonist activity. Second, the EP50 value was 26.4-fold lower than the agonist/antagonist Ki ratio for CP55,940/rimonabant versus only 6-fold lower for fentanyl/naltrexone. This suggests higher sensitivity of [35S]GTPγS binding to agonist activity and higher receptor reserve in mCB1R-CHO than mMOR-CHO cells. This high sensitivity of mCB1R-CHO cells may be related to 1) constitutive mCB1R activity [which increases the degree to which low-efficacy ligands produce full-agonist effects (Negus, 2006)] or 2) the higher receptor density in mCB1R-CHO versus mMOR-CHO cells. Lastly, despite the high sensitivity of the mCB1R-CHO cells, in vivo thermal antinociception still had an even lower EP50 value, suggesting that high CB1R sensitivity also exists in vivo.

Summary.

Overall, this study confirms and extends prior research with agonist/antagonist mixtures. Manipulation of agonist proportion in these mixtures governs net mixture efficacy at the target receptor. The EP50 value of agonist/antagonist mixtures provides a quantitative metric for comparison of efficacy requirements across any type of endpoint in any species, and slope values provide an indication of the dynamic range of sensitivity to receptor-mediated effects. Among other possible applications, this quantification of efficacy requirements across endpoints can be used to guide development of drugs with efficacy sufficient to produce desirable effects but insufficient to produce at least a subset of undesirable effects.

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CB1R

cannabinoid type 1 receptor

- CP55,940

(2-[(1R,2R,5R)-5-hydroxy-2-(3-hydroxypropyl)cyclohexyl]-5-(2-methyloctan-2-yl)phenol

- DAMGO

[d-Ala2,N-MePhe4,Gly5-ol]enkephalin

- Emax

maximum effect

- EP50

agonist proportion in an agonist/antagonist mixture to produce 50% agonist-alone Emax

- MOR

μ-opioid receptor

- %MPE

percent maximum possible effect

- OUD

opioid use disorder

- [35S]GTPγS

guanosine 5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate

- WIN55,212-2

(11R)-2-methyl-11-[(morpholin-4-yl)methyl]-3-(naphthalene-1-carbonyl)-9-oxa-1-azatricyclo[6.3.1.04,12]dodeca-2,4(12),5,7-tetraene

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Selley, Banks, Negus.

Conducted experiments: Diester, Jali, Legakis, Santos.

Performed data analysis: Selley, Diester, Jali, Legakis, Santos, Negus.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Selley, Banks, Diester, Jali, Legakis, Santos, Negus.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grants R01-DA030404, P30-DA033934, F31-DA051163], National Cancer Institute [Grant F30-CA213956], and National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant R25-GM090084].

No author has an actual or perceived conflict of interest with the contents of this article.

References

- Blumenthal DK (2018) Pharmacodynamics: molecular mechanisms of drug action, in Goodman and Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 13e (Brunton LL, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollmann BC eds) McGraw-Hill, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Bouaboula M, Perrachon S, Milligan L, Canat X, Rinaldi-Carmona M, Portier M, Barth F, Calandra B, Pecceu F, Lupker J, et al. (1997) A selective inverse agonist for central cannabinoid receptor inhibits mitogen-activated protein kinase activation stimulated by insulin or insulin-like growth factor 1. Evidence for a new model of receptor/ligand interactions. J Biol Chem 272:22330–22339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivogel CS, Selley DE, Childers SR (1998) Cannabinoid receptor agonist efficacy for stimulating [35S]GTPgammaS binding to rat cerebellar membranes correlates with agonist-induced decreases in GDP affinity. J Biol Chem 273:16865–16873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childers SR (1991) Opioid receptor-coupled second messenger systems. Life Sci 48:1991–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen JC, Obeng S, Rice KC, Zhang Y, Negus SS, Banks ML (2018) Application of receptor theory to the design and use of fixed-proportion mu-opioid agonist and antagonist mixtures in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 365:37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmerson PJ, Clark MJ, Mansour A, Akil H, Woods JH, Medzihradsky F (1996) Characterization of opioid agonist efficacy in a C6 glioma cell line expressing the mu opioid receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 278:1121–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmerson PJ, Liu MR, Woods JH, Medzihradsky F (1994) Binding affinity and selectivity of opioids at mu, delta and kappa receptors in monkey brain membranes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 271:1630–1637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis A, Sreenivasan V, Christie MJ (2020) Intrinsic efficacy of opioid ligands and its importance for apparent bias, operational analysis and therapeutic window. Mol Pharmacol 98:410–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grim TW, Morales AJ, Gonek MM, Wiley JL, Thomas BF, Endres GW, Sim-Selley LJ, Selley DE, Negus SS, Lichtman AH (2016) Stratification of cannabinoid 1 receptor (CB1R) agonist efficacy: manipulation of CB1R density through use of transgenic mice reveals congruence between in vivo and in vitro assays. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 359:329–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grim TW, Morales AJ, Thomas BF, Wiley JL, Endres GW, Negus SS, Lichtman AH (2017) Apparent CB1 receptor rimonabant affinity estimates: combination with THC and synthetic cannabinoids in the mouse in vivo triad model. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 362:210–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Manglik A, Venkatakrishnan AJ, Laeremans T, Feinberg EN, Sanborn AL, Kato HE, Livingston KE, Thorsen TS, Kling RC, et al. (2015) Structural insights into µ-opioid receptor activation. Nature 524:315–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide S, Minami M, Sora I, Ikeda K (2010) Combination of cell culture assays and knockout mouse analyses for the study of opioid partial agonism. Methods Mol Biol 617:363–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Reed B, Butelman ER (2019) Current status of opioid addiction treatment and related preclinical research. Sci Adv 5:eaax9140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsman RS, Burkey TH, Consroe P, Roeske WR, Yamamura HI (1997) SR141716A is an inverse agonist at the human cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Eur J Pharmacol 334:R1–R2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipworth BJ, Grove A (1997) Evaluation of partial beta-adrenoceptor agonist activity. Br J Clin Pharmacol 43:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (2011) Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academies Press, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS (2006) Some implications of receptor theory for in vivo assessment of agonists, antagonists and inverse agonists. Biochem Pharmacol 71:1663–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffa RB, Haidery M, Huang HM, Kalladeen K, Lockstein DE, Ono H, Shope MJ, Sowunmi OA, Tran JK, Pergolizzi JV Jr (2014) The clinical analgesic efficacy of buprenorphine. J Clin Pharm Ther 39:577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Chambers LK, Coe JW, Glowa J, Hurst RS, Lebel LA, Lu Y, Mansbach RS, Mather RJ, Rovetti CC, et al. (2007) Pharmacological profile of the alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline, an effective smoking cessation aid. Neuropharmacology 52:985–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwienteck KL, Faunce KE, Rice KC, Obeng S, Zhang Y, Blough BE, Grim TW, Negus SS, Banks ML (2019) Effectiveness comparisons of G-protein biased and unbiased mu opioid receptor ligands in warm water tail-withdrawal and drug discrimination in male and female rats. Neuropharmacology 150:200–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selley DE, Liu Q, Childers SR (1998) Signal transduction correlates of mu opioid agonist intrinsic efficacy: receptor-stimulated [35S]GTP gamma S binding in mMOR-CHO cells and rat thalamus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 285:496–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selley DE, Sim LJ, Xiao R, Liu Q, Childers SR (1997) mu-Opioid receptor-stimulated guanosine-5′-O-(gamma-thio)-triphosphate binding in rat thalamus and cultured cell lines: signal transduction mechanisms underlying agonist efficacy. Mol Pharmacol 51:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sounier R, Mas C, Steyaert J, Laeremans T, Manglik A, Huang W, Kobilka BK, Déméné H, Granier S (2015) Propagation of conformational changes during μ-opioid receptor activation. Nature 524:375–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe KJ, Henderson G, Kelly E, Sessions RB (2017) Drug binding poses relate structure with efficacy in the μ opioid receptor. J Mol Biol 429:1840–1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga CA, Carlsson A (2002) Partial dopamine agonists and dopaminergic stabilizers, in the treatment of psychosis. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord 1:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toombs JD, Kral LA (2005) Methadone treatment for pain states. Am Fam Physician 71:1353–1358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor JR, Nahorski SR (1995) Modulation by mu-opioid agonists of guanosine-5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate binding to membranes from human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Mol Pharmacol 47:848–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL, Wallace M (2018) Opioids, analgesia, and pain management, in Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 13e (Brunton LL, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollmann BC, eds) pp 355–386, McGraw-Hill, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Yocca FD (1990) Neurochemistry and neurophysiology of buspirone and gepirone: interactions at presynaptic and postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors. J Clin Psychopharmacol 10 (Suppl):6S–12S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y, Elbegdorj O, Beletskaya IO, Selley DE, Zhang Y (2013) Structure activity relationship studies of 17-cyclopropylmethyl-3,14β-dihydroxy-4,5α-epoxy-6α-(isoquinoline-3′-carboxamido)morphinan (NAQ) analogues as potent opioid receptor ligands: preliminary results on the role of electronic characteristics for affinity and function. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 23:5045–5048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]