Abstract

Introduction

Spinal anesthesia (SA) has been shown in several studies to be a viable alternative to general anesthesia (GA) in laminectomies, discectomies, and microdiscectomies. However, the use of SA in spinal fusion surgery has been very scarcely documented in the current literature. Here we present a comparison of SA to GA in lumbar fusion surgery in terms of perioperative outcomes and cost.

Methods

The authors retrospectively reviewed the charts of all patients who underwent 1- or 2-level minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) surgery by a single surgeon, at a single institution, from 2015 to 2018. Data collected included demographics, operative and recovery times, nausea/vomiting, postoperative pain, and opioid requirement. Costs were included in the analysis if they were: 1) non-fixed; 2) incurred in the operating room (OR); and 3) directly related to patient care. All cost data represents net costs and was obtained from the hospital revenue cycle team. Patients were grouped for statistical analysis based on anesthetic modality.

Results

A total of 29 patients received SA and 46 received GA. Both groups were similar in terms of age, gender, BMI, number of levels operated upon, preoperative diagnosis, and medical comorbidities. The SA group spent less time in the OR (163.86 ± 9.02 vs. 195.63 ± 11.27 min, p < 0.05), PACU (82.00 ± 7.17 vs. 102.98 ± 8.46 min, p < 0.05), and under anesthesia (175.03 ± 9.31 vs. 204.98 ± 10.15 min, p < 0.05) than the GA group. Post-surgery OR time was significantly less with SA than with GA (6.00 ± 1.09 vs. 17.26 ± 3.05 min, p < 0.05); however, pre-surgery OR time was similar between groups (50.17 ± 3.08 vs. 56.17 ± 5.34 min, p = 0.061). The SA group also experienced less maximum postoperative pain (3.31 ± 1.41 out of 10 vs. 5.96 ± 0.84/10, p < 0.05) and required less opioid analgesics (2.38 ± 1.37 vs. 5.39 ± 0.84 doses, p < 0.05). Both groups experienced similar nausea or vomiting rates and adverse events postoperatively. Net operative cost was found to be $812.31 (5.6%) less with SA than with GA, although this difference was not significant (p = 0.225).

Discussion/conclusion

To our knowledge, SA is almost never used in lumbar fusion, and a cost-effectiveness comparison with GA has not been recorded. In this retrospective study, we demonstrate that the use of SA in lumbar fusion surgery leads to significantly shorter operative and recovery times, less postoperative pain and opioid usage, and slight cost savings over GA. Thus, we conclude that this anesthetic modality represents a safe and cost-effective alternative to GA in lumbar fusion.

Keywords: Spinal anesthesia, Lumbar fusion, Spine surgery, General anesthesia, Comparative outcome analysis

Conflicts of interest and source of funding

Alok Sharan has received consulting fees from Depuy and Paradigm Spine.

1. Introduction

Spine surgery is widely performed under the use of general anesthesia (GA). The diverse range of procedures include fusion surgeries, lumbar laminectomies, discectomies, and microdiscectomies. Use of GA is attributed to primary surgeon preference, patient desire for the procedural standard, and anesthesiologist comfort. The use of GA, however, is not without its complications, and can lead to postoperative nausea, vomiting, and even cardiovascular and pulmonary complications. Ultimately, this can result in longer post-operative hospital stays and increased costs to both the patient and hospital. With the rising age of the population across the United States, and the increased need for lumbar spine surgery, alternate modalities may prove beneficial regarding long term outcomes.

Regional anesthesia has been alternatively used for a number of spinal procedures, with spinal anesthesia (SA) being the most common for laminectomies, discectomies, and microdiscectomies.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Unfortunately, there is limited literature documenting the use of SA in lumbar fusion surgery. Certain studies have been performed evaluating the differences between GA and SA in regards to complication rates, patient and surgeon satisfaction, pain control, hemodynamic variables, operative time, anesthesia time, and recovery time.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19 The majority of these studies found the use of SA was associated with patients experiencing less pain, less operative and recovery time, greater patient satisfaction, and less blood loss with decreased MAP and HR.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 However, other studies assessing the differences between GA and SA found no difference in hemodynamic parameters, surgery time, or recovery time.15,16 Given the lack of uniformity between various studies, there remains a debate regarding the effectiveness of SA for spinal procedures over GA.

In light of mounting healthcare costs and increased burdens placed on patients and hospitals, further analysis and comparison of all techniques that would improve post-operative outcomes is needed.17 Thus, the objective of this study is to evaluate the post-operative outcomes of SA and GA in minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF). Procedures utilizing both modalities were retrospectively compared in regard to postoperative pain, medication usage, and adverse events. Additionally, perioperative parameters will be analyzed, and net costs will be documented. With this added information, we hope to help guide and modify the standard of care and promote discussion on various anesthetic modalities that can be utilized in lumbar fusion surgery.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients

A total of 75 patients underwent minimally invasive TLIF surgery by a single surgeon at a single institution from 2015 to 2018. There were 36 males and 39 females with an age range of 20–87 years old. The main diagnoses for these patients were spondylolisthesis (present in 58 patients) and spinal stenosis (57 patients), while degenerative disc disease (5) and herniated discs (3) were less commonly seen.

Patients undergoing minimally invasive TLIF were included in the study. Patients were stratified into two groups based on anesthetic modality: General Anesthesia or Spinal Anesthesia. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. The risks, benefits, and alternatives were presented to the patients by the surgeon.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained in order to access patient medical records. The authors retrospectively reviewed each of the patients’ charts, evaluating the outcomes and costs of the patients within the two anesthesia groups for statistical comparison. Patient data was de-identified.

2.2. Anesthetic technique

For SA patients, isobaric bupivacaine was administered locally; sedation was achieved using short-acting intravenous agents. GA was achieved using a balanced technique through use of an endotracheal tube.

2.3. Perioperative and postoperative data

Patient demographic information, BMI, diagnosis, comorbidities, levels operated on, total OR time (time spent in OR), total surgery time (time from incision to closure), time under anesthesia, post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) time, pain scores, adverse events, nausea/vomiting rates, opioid doses, and days spent in the hospital were collected.

Procedural costs were gathered and analyzed. Costs were included in the analysis if they were: 1) non-fixed; 2) incurred in the operating room; and 3) directly related to patient care. Costs consisted of the total direct cost plus PACU cost plus cost of anesthesia. All cost data represents net costs, or the cost the hospital pays for goods or services rather than the cost billed to patients or insurers. Total direct cost was obtained from the hospital revenue cycle team, who were blinded from the study.

In order to assess opioid usage, dose calculations were standardized. One dose of opioid medication was considered to be equivalent to: 2 mg morphine IV, 0.25 mg hydromorphone IV, 25 mcg fentanyl SQ, 5 mg oxycodone PO, 10 mg hydrocodone PO, 50 mg tramadol PO, and 30 mg codeine PO.

2.4. Anesthetic modality comparison

Significant differences in outcome or costs were determined to be 0.05. Two-tailed, unequal variance, student’s t-test analyses were performed for continuous variables, and chi-squared analyses were performed for categorical variables. The GA group was compared to the SA group. Mean, standard deviation, and 95% C.I. were calculated. Results are indicated with mean ± 95% C·I.

3. Results

A total of 75 patients undergoing spinal fusion were included in this study. 46 received GA and 29 received SA. Demographic and baseline characteristics of patients were similar in both of the anesthetic modalities used in lumbar fusion surgery (Table 1). There was no significant difference in age, gender, BMI, preoperative diagnosis, levels operated on, and ASA physical score (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics. Demographic data for both anesthetic modalities including number of patients, age, sex, BMI, comorbidities, diagnosis, and levels of spinal procedures. The sum of patients with each preoperative diagnosis exceeds 100% of patients, as many patients in each group carried more than one diagnosis. All listed values utilize 95% confidence intervals as measures of precision.

| Anesthetic modality |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SA | GA | ||

| Number of Patients | 29 | 46 | – |

| Age | 61.79 ± 5.63 | 61.39 ± 2.69 | 0.900 |

| Sex (M/F) | 16/13 | 20/26 | 0.444 |

| BMI | 29.535 ± 1.83 | 29.86 ± 1.67 | 0.688 |

| Comorbidities (ASA Score) | 2.24 ± 0.23 | 2.13 ± 0.14 | 0.464 |

| Preoperative diagnosis: | |||

| Spondylolisthesis | 55.17% | 91.30% | 0.086 |

| Spinal Stenosis | 79.31% | 73.91% | |

| Other | 27.5% | 6.52% | |

| Number of spinal levels | 1.03 ± 0.66 | 1.07 ± 0.07 | 0.544 |

Regarding perioperative outcomes, the SA group compared to the GA group spent less total time in the OR (p < 0.0001), less time in surgery (p = 0.02), less time under anesthesia (p < 0.0001), and less time in the PACU (p < 0.001) (Table 2). Moreover, the SA group had reduced post-surgery OR time (p < 0.0001), although pre-surgery OR time was not significantly different between SA and GA (data not shown) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Time Parameters. Average OR time, Total Surgery time, Anesthesia time, and total PACU time for each group. All times in this chart are listed in minutes. All listed values utilize 95% confidence intervals as measures of precision.

| Anesthetic modality |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SA | GA | ||

| OR time | 163.86 ± 9.02 | 195.63 ± 11.27 | < 0.0001 |

| Surgery time | 107.69 ± 7.52 | 122.20 ± 9.39 | 0.019 |

| Anesthesia time | 175.03 ± 9.31 | 204.97 ± 10.15 | < 0.0001 |

| PACU time | 82.00 ± 7.17 | 102.98 ± 8.46 | < 0.001 |

| Time Savings (%) | |

|---|---|

| OR time | 16.20% |

| Surgery time | 11.87% |

| Anesthesia time | 14.61% |

| PACU time | 20.4% |

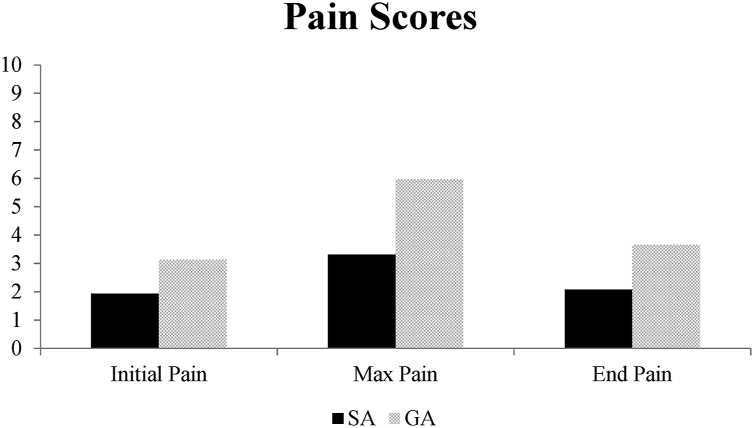

The SA group had lower postoperative max pain scores (p = 0.002), lower pain scores leaving the PACU (p = 0.008) and required less opioid doses (p = 0.002) than the GA group (Fig. 1, Table 3). Fewer patients required opioids and had a longer time to first opioid dose (Table 3). Adverse events, nausea/vomiting rates, and readmission rates were similar for each group. Data was not significant when comparing average length of stay between the SA and GA groups.

Fig. 1.

Initial, Max, and End Pain score comparison. Patients in the PACU reported their pain scores upon entering and leaving the PACU, as well as throughout their stay. Max pain score and pain leaving the PACU was significantly lower in the SA group.

Table 3.

Perioperative Outcomes. Nausea/vomiting rates, initial, final, and max PACU pain score (reported by the patient on a scale of 1–10), patients requiring opioid doses, opioid doses given, time to first opioid dose, average length of stay, and 30-day readmission rates were recorded. Doses of opioids were calculated as noted in the Methods section. Time to first opioid indicates time elapsed from entering the PACU to first administration of opioid medication. All listed values utilize 95% confidence intervals as measures of precision.

| Anesthetic modality |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SA | GA | ||

| Nausea/vomiting n (%) | 12 (41.38%) | 23 (50.00%) | 0.466 |

| Initial PACU pain (1–10) | 1.93 ± 1.38 | 3.13 ± 1.10 | 0.162 |

| End PACU pain (1–10) | 2.07 ± 0.94 | 3.65 ± 0.62 | < 0.01 |

| Max PACU Pain (1–10) | 3.31 ± 1.41 | 5.96 ± 0.84 | < 0.01 |

| Patients requiring opioids in PACU | 18 (62.07%) | 40 (86.96%) | < 0.01 |

| Opioids given in PACU (doses) | 2.38 ± 1.37 | 5.39 ± 0.84 | < 0.01 |

| Time to first opioid admin. (min) | 80.38 ± 15.97 | 29.30 ± 5.76 | < 0.001 |

| Average length of stay (days) | 0.97 ± 0.21 | 1.30 ± 0.33 | 0.091 |

| 30-day readmission rate | 3.09% | 2.17% | 0.98 |

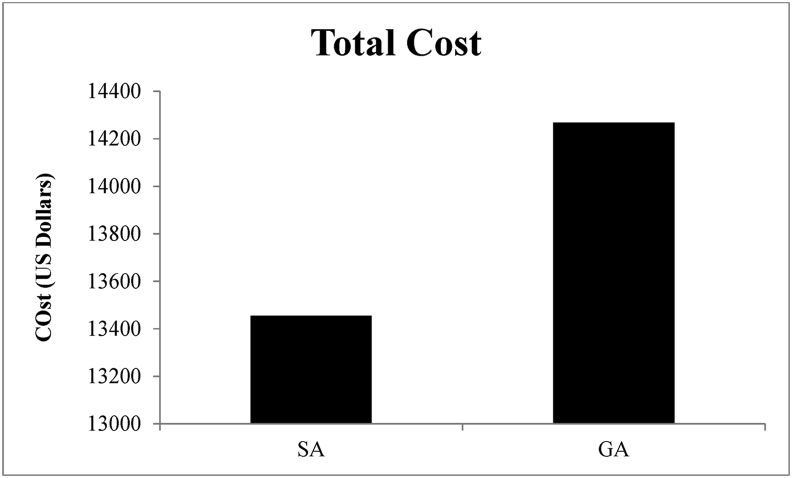

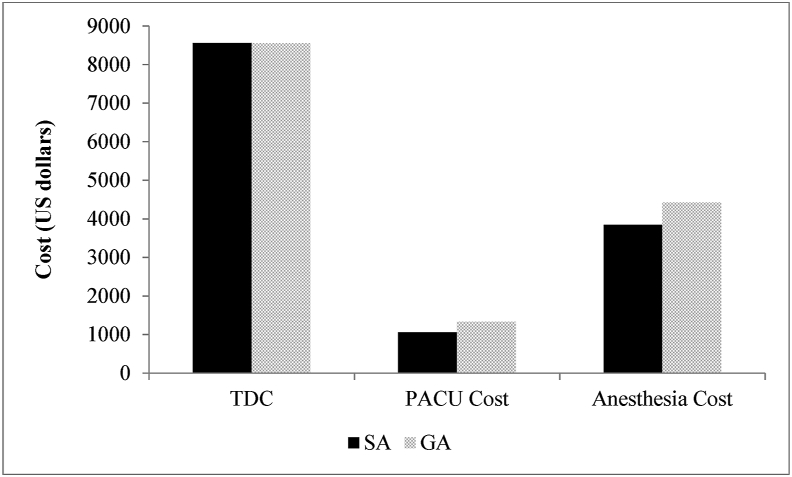

Use of SA resulted in a total net operative cost saving of $812.31, or 5.6%, over GA (Fig. 2, Table 4), although this reduced cost was not statistically significant (p = 0.225). A breakdown of the cost analysis revealed statistically significant differences in PACU and Anesthesia cost, although Total Direct Cost was similar (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Total Cost Comparison. Comparison of total costs of SA and GA. Lumbar fusion surgeries utilizing SA as the anesthetic technique cost $812.31 less, or provided a cost savings of 5.6%.

Table 4.

Costs. Total direct cost, anesthesia cost, PACU cost, and sum total costs were calculated. All costs in this chart are listed in US dollars ($). All listed values utilize 95% confidence intervals as measures of precision.

| Anesthetic modality |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SA | GA | ||

| Total direct cost | 8557.22 ± 965.93 | 8550.26 ± 539.24 | 0.990 |

| Anesthesia cost | 3841.38 ± 121.92 | 4417.39 ± 138.71 | < 0.0001 |

| PACU costs (total) | 1056.93 ± 104.82 | 1328.91 ± 115.88 | 0.020 |

| Total cost | 13455.36 ± 1131.54 | 14267.67 ± 625.93 | 0.220 |

Fig. 3.

Itemized cost comparison for SA and GA. Detailed cost comparison in SA and GA in terms of Total Direct Cost (TDC), PACU cost, and Anesthesia cost. PACU cost and Anesthesia cost were significantly lower in SA compared to GA.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that the use of spinal anesthesia for lumbar fusion surgery resulted in lower postoperative pain and opioid usage, reduced operative and recovery times, along with cost savings when compared to individuals who had general anesthesia. . The data from this study indicates that SA is a useful and beneficial alternative to GA for lumbar fusion surgery. Cost effectiveness and overall improvement in outcomes can not be demonstrated at this point from this study. However, the findings we present in this study are in line with previous studies comparing SA to GA in a variety of different lumbar spine procedures.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

One important outcome of this study was significantly reduced postoperative pain reported by patients in the SA group following fusion surgery. This has also been observed consistently in many reports regarding lumbar spine surgeries,1,3,5, 6, 7 and our study illustrates that SA can lower both maximum postoperative pain and pain upon leaving the PACU. One possible explanation for this is the more dominant effect of spinal anesthesia on afferent nociceptive pathway.14,21 These pain fibers are smaller than motor fibers and thus have delayed recovery compared to motor fibers.Therefore, the pain relief may last into the postoperative setting despite return of motor function.

Associated with lower reported pain scores, the SA group also demonstrated significant differences in opioid usage in the PACU compared to patients receiving GA. Fewer patients required opioids, the patients who needed opioids required less doses, and there was a longer period of time before the first opioid dose was needed to be administered in the SA group. The indication is directly correlated with postoperative pain: less pain requires less opioids for the SA group.

In addition to the findings mentioned above, our results illustrate significantly reduced perioperative times for patients receiving SA. Patients spent less time in the OR, less time under anesthesia, less time in surgery, and less time in the PACU. Each of these outcomes can be attributed to the inherent differences of SA and GA as anesthetic modalities. While GA may reduce time to induction,6 total time under anesthesia, and thus total OR time, may be longer in GA because it takes a longer period of time to assess patient responsiveness and respiratory function. Therefore, SA may improve anesthetic recovery time, which could potentially account for decreased discomfort seen postoperatively. Additionally, it has been reported that the use of SA compared to GA has been associated with significantly fewer rates of intraoperative intravenous medication administration.22 Decreased intraoperative medication use can also contribute to reduced OR time.

In order to accurately assess and compare the effectiveness of SA to GA, we analyzed the costs incurred for each group. The total net operative cost savings when using SA was $812.31, or 5.6%; however, this was not statistically significant. Stratifying total cost into total direct cost, anesthetic cost, and PACU cost revealed substantial differences. Total direct costs were costs experienced in the OR, including hospital-reported direct cost, and sterile supply cost; the total direct cost values for SA and GA were nearly identical. Conversely, the anesthetic costs and PACU costs were significantly different, demonstrating that cost savings are primarily due to the effect of SA in reducing anesthetic costs and costs in the PACU. While a cost savings of 5.6% is valuable it is less than other reported cost savings,18 most likely due to direct OR costs constituting the majority of total cost for each anesthetic modality.20

A limitation of this study includes analyzing only those outcomes that are reported and thus only those that can be retrospectively reviewed. An important outcome that is measurable and valuable in this analysis is surgeon and patient satisfaction. While previous studies have found increased surgeon satisfaction in other lumbar procedures,4, 5, 6 others have found surgeon inexperience with SA to be unsatisfactory.15,16 Evaluating patient satisfaction could prove to be very beneficial and aid in committing to SA as the standard of care for lumbar fusion surgery, and should be investigated in future studies. Furthermore, a more comprehensive analysis of adverse outcomes should be reported in future trials. This study was limited to analyzing only the data that was recorded, noting outcomes such as nausea/vomiting rates, length of stay, and 30-day readmission rates. Studies going forward can document estimated blood loss, hemodynamic variables intraoperatively, and procedural-related health complications postoperatively with follow-up care. Further limitations to the study include the sample size, restricted to a single surgeon’s practice. Implementing a larger randomized prospective study would increase the power of the study and additionally help limit differences in baseline characteristics. Selection bias may also have played a role, as the decision between use of spinal anesthesia vs general anesthesia was under the discretion of the patient and provider. A randomized protocol also addresses this issue, and further increases significance.

5. Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that the use of SA in lumbar fusion surgery corresponds with less time spent in the OR, under anesthesia, and in the PACU, in addition to less postoperative pain and opioid usage than GA. Moreover, SA is associated with a cost savings of 5.6%, without any difference in nausea/vomiting rates, length of stay, or 30-day readmission rates. Therefore, based on the results of this study we conclude that SA is a superior and more cost-effective alternative to GA in lumbar fusion surgery.

References

- 1.Jellish W.S., Thalji Z., Stevenson K. A prospective randomized study comparing short- and intermediate-term perioperative outcome variables after spinal or general anesthesia for lumbar disk and laminectomy surgery. Anesth Analg. 1996 Sep;83(3):559–564. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199609000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLain R.F., Bell G.R., Kalfas I. Complications associated with lumbar laminectomy: a comparison of spinal versus general anesthesia. Spine. 2004 Nov 15;29(22):2542–2547. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000144834.43115.38. (Phila Pa 1976) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLain R.F., Kalfas I., Bell G.R. Comparison of spinal and general anesthesia in lumbar laminectomy surgery: a case-controlled analysis of 400 patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005 Jan;2(1):17–22. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.1.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLain R.F., Tetzlaff J.E., Bell G.R. Microdiscectomy: spinal anesthesia offers optimal results in general patient population. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2007;16(1):5–11. Spring. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Rojas J.O., Syre P., Welch W.C. Regional anesthesia versus general anesthesia for surgery on the lumbar spine: a review of the modern literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014 Apr;119:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attari M., Mirhosseini S., Honarmand A. Spinal anesthesia versus general anesthesia for elective lumbar spine surgery: a randomized clinical trial. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:524–529. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dagher C., Naccache N., Narchi P. Regional anesthesia for lumbar microdiscectomy. J Med Liban. 2002 Sep-Dec;50(5-6):206–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demeril C.B., Kalayci M., Ozkocak I. A prospective randomized study comparing peri-operative outcome variables after epidural of general anesthesia for lumbar disc surgery. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2003;15(3):158–192. doi: 10.1097/00008506-200307000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ulutas M., Secer M., Taskapilioglu O. General versus epidural anesthesia for lumbar microdiscectomy. J Clin Neurosci. 2015 Aug;22(8):1309–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singeisen H., Hodel D., Schindler C. Significantly shorter anesthesia time for surgery of the lumbar spine: process analytical comparison of spinal anesthesia and intubation narcosis. Anaesthesist. 2013 Aug;62(8):632–638. doi: 10.1007/s00101-013-2204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lessing N.L., Edwards C.C., II, Brown C.H., IV Orthopedics. 2017 Mar 1;40(2):e317–e322. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20161219-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tetzlaff J.E., Dilger J.A., Kodsy M. Spinal anesthesia for elective lumbar spine surgery. J Clin Anesth. 1998;10:666–669. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(98)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen H.T., Tsai C.H., Chao S.C. Endoscopic discectomy of L5-S1 disc herniation via an interlaminar approach: prospective controlled study under local and general anesthesia. Surg Neurol Int. 2011;2:93. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.82570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassi N., Badaoui R., Cagny-Bellet A. Spinal anesthesia for disk herniation and lumbar laminectomy. Apropos of 77 cases. Cah Anesthesiol. 1995;43(1):21–25. Cah Anesthesiol. 1995;43(1):21-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahveci K., Doger C., Ornek D. Perioperative outcome and cost-effectiveness of spinal versus general anesthesia for lumbar spine surgery. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2014;48(3):167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.pjnns.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadrolsadat S.H., Mahdavi A.R., Moharari R.S. A prospective randomized trial comparing the technique of spinal and general anesthesia for lumbar disk surgery: a study of 100 cases. Surg Neurol. 2009 Jan;71(1):60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinstein J.N., Lurie J.D., Olson P.R. United States’ trends and regional variations in lumbar spine surgery: 1992-2003. Spine. 2006;31:2707–2714. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000248132.15231.fe. (Phila Pa 1976) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agarwal P., Pierce J., Welch W.C. Cost analysis of spinal versus general anesthesia for lumbar diskectomy and laminectomy spine surgery. World Neurosurg. 2016 May;89:266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walcott B.P., Khanna A., Yanamadala V. Cost analysis of spinal and general anesthesia for the surgical treatment of lumbar spondylosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2015 Mar;22(3):539–543. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2014.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonano C., Leitgeb U., Sitzwohl C. Spinal versus general anesthesia for orthopedic surgery: anesthesia drug and supply costs. Anesth Analg. 2006 Feb;102(2):524–529. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000194292.81614.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Covino B.G. Rationale for spinal anesthesia. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 1989 Spring;27(1):8–12. doi: 10.1097/00004311-198902710-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng H., Coumans J.V., Anderson R., Houle T.T., Peterfreund R.A. Spinal anesthesia for lumbar spine surgery correlates with fewer total medications and less frequent use of vasoactive agents: a single center experience. PloS One. 2019;14(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]