Abstract

Introduction

A variety of fracture patterns are seen in supracondylar humerus fractures in children and these are well described by Bahk et al. Currently followed treatment protocol doesn’t recognize these common fracture patterns and pin placement is done at the discretion of the treating surgeon. The aim of the study is to evaluate the usefulness of Bahk classification system in deciding the pin configuration for the specific fracture patterns and thereby assess the functional outcome in the management of supracondylar fractures in children.

Method

The study was done on 100 children of 2–12 years of age from February 2019 to January 2020. After closed reduction under general anesthesia, fractures were classified and pin configuration was decided according to Bahk classification. In the follow-up, patients were assessed for clinicoradiological outcomes based on Modified Flynn’s criteria, Baumann angle, and anterior humeral line.

Results

In our study Typical transverse and low sagittal fracture were the most common fracture patterns. In the final follow up as per Flynn’s criteria, 93% of the patients showed excellent results. Mean Baumann’s angle was not significantly different from the uninjured side and anterior humeral line passed through anterior or middle third of the capitulum in 95% patients.

Conclusion

Using pin configuration suitable to fracture pattern as per Bahk classification improves functional outcome in supracondylar humerus fractures in children and minimizes complications.

Keywords: Supracondylar humerus, Bahk classification, Flynn criteria, Baumann angle, Anterior humeral line

1. Introduction

Apart from Gartland classification for supracondylar humerus fractures; a wide variety of fracture patterns in supracondylar humerus have been identified based on the fracture line in sagittal and coronal planes.1 Biomechanical studies and relevant literatures have suggested that lateral pin configuration is not sufficient to maintain reduction and provide stability in all patterns of supracondylar fractures. Cross pin configuration increases the stability of the construct in unstable fractures but placement of medial pin is associated with an increased incidence of ulnar nerve injury.2 The current treatment protocol has no guidelines to recognize different fracture patterns and pin placement is being done at the discretion of the treating surgeon.3 Bahk et al., in 2008 devised a classification based on fracture patterns in the coronal and sagittal plane and proposed pin configuration specific to fracture pattern. The Bahk classification is based on the angle the fracture line makes with the line perpendicular to the distal humerus axis. In the anteroposterior (AP) view this is described as “coronal obliquity” and in the lateral view as “sagittal obliquity”. Coronal obliquity >10° (medial oblique and lateral oblique varieties) are associated with more comminutions and rotational malalignments. Sagittal obliquities >20° (high sagittal) are associated with rotational mal-unions and associated with other injuries.3

The aim of the study is to evaluate the usefulness of Bahk classification system in deciding the pin configuration for specific fracture patterns and thereby access the functional outcome in the management of supracondylar fractures in children.

2. Method

After approval from the Institutional Review Board, a prospective study was conducted from February 2019 to January 2020 on 100 children of age group 2–12 years who had sustained Gartland type III Supracondylar humerus fractures which also included supracondylar fractures with neurovascular injuries.

Exclusion criteria were as

-

i.

Patients with type I and type II Gartland fractures

-

ii.

Open fractures

-

iii.

Associated with other fractures in the ipsilateral upper limb.

-

iv.

Patients with history of deformity, contracture, and neuro deficit in the ipsilateral upper limb before the trauma.

Thorough clinical and neurovascular examinations were done on admission. An above elbow slab was applied for initial immobilization. The children were then planned for definitive treatment at the earliest and a fixed protocol of pin configuration as per Bahk classification was formulated. Preoperative planning was done in the operation theatre after general anesthesia and closed reduction done by Blount’s technique.4 The fracture pattern was visualized and confirmed by intraoperative dynamic imaging or fluoroscopy. Coronal obliquity was determined by identifying the axis of distal humerus on the anteroposterior view. The fracture line was identified by marking the medial and lateral ends of the fracture on the medial and lateral pillar of the distal humerus. The angle formed by the fracture line with the line perpendicular to the humerus axis was measured. Based on this, four fracture patterns were identified as described by Bahk. Typical transverse fractures were the fractures with coronal obliquity less than 10° and fracture line extending to near the medial and lateral epicondyle on the medial and lateral pillar respectively. Lateral oblique fractures were the fractures with coronal obliquity >10° with proximal fracture line exiting laterally. Medial oblique fractures were the fractures with coronal obliquity >10° with proximal fracture line exiting medially. High transverse fractures had coronal obliquity <10° and fracture line entering and exiting above the olecranon fossa but within the distal humeral epiphysis. Sagittal obliquity was measured in a lateral view based on the angle between the fracture line and the distal humeral axis. Low sagittal oblique fractures were the fractures with sagittal obliquity <20° whereas high sagittal oblique fractures with obliquity >20°. The choice of pin configuration was determined as suggested by Bahk et al.:

-

i.

2 lateral pins for lateral oblique and low transverse fracture patterns in the coronal plane and low sagittal fractures

-

ii.

Cross pinning for medial oblique fractures

-

iii.

Either 3 lateral pins if the proximal purchase of all the three pins were possible or 2 lateral and 1 medial pin; for high transverse and high sagittal fracture patterns.3

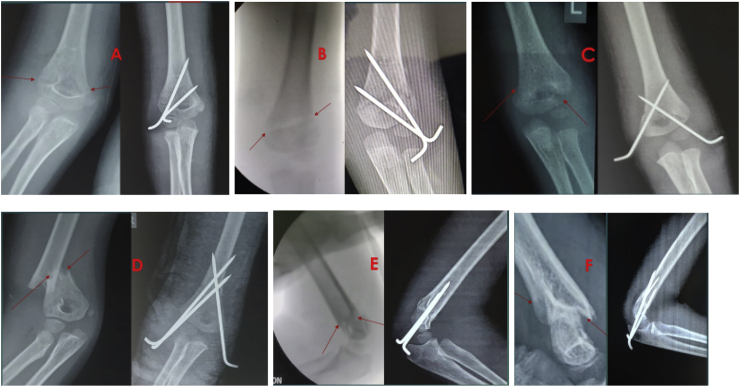

Fig. 1 shows preoperative and postoperative X-rays of different fracture patterns and pin fixation in our study according to Bahk classification.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative & Postoperative X-rays showing different fracture patterns and pin configuration according to Bahk classification.

A – D in Coronal plane; A: Typical transverse fixed with 2 lateral pins. B: Lateral oblique fracture fixed with 2 lateral pins. C: Medial oblique fixed with crossed pins. D: High Transverse fracture fixed with 2 lateral and 1 medial pin.

E-F in Sagittal Plane; E: Low Saggital fixed with 2 pins. F: High Saggital fixed with 3 pins.

After achieving reduction, the lateral pin/pins were inserted in elbow flexion under fluoroscopic guidance. If a medial pin was required, a small incision was taken on the medial aspect of the elbow and soft tissue was separated with artery forceps.5 The elbow was extended to prevent nerve entrapment.6 It was further protected by placing the surgeon’s thumb on the medial condyle posterior to the cubital tunnel protecting the nerve.7 After both the pins were placed, the stability of the configuration was checked under fluoroscopy and Baumann’s angle was measured. An above elbow slab was then applied.

The patients were monitored postoperatively for neurovascular integrity and signs of compartment syndrome and discharged after 24 h of post-anesthesia monitoring.

The first follow up was done at 3 weeks postoperatively. Radiographic and clinical evaluations were done. If there were radiological signs of union; K wires were removed and the patients were started on a range of motion exercises otherwise weekly follow-up of the patient was done till signs of union were evident. After K wire removal, monthly follow-ups were performed with radiographic evaluation for 3 consecutive months.

The patients’ functional outcomes were assessed based on Modified Flynn’s criteria8 for which range of motion of the elbow and carrying angle were measured with a goniometer and compared with the opposite side to measure the degree of loss of flexion and carrying angle. Radiological criteria such as Baumann’s angle and anterior humeral line were assessed in the follow-up.

Data Analysis and Interpretation: Data were entered into Microsoft Excel (Windows 7; Version 2007) and analyses were done using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) for Windows software (version 22.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago). Descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables, frequencies, and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Association between variables was analyzed by using McNemar for categorical variables and paired t-test for comparison of quantitative variables pre-op and post-op. Bar charts and Pie charts were used for the visual representation of the analyzed data. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

3. Results

In our study, the mean age of the patients was 6.23 years with 58% of the children below the mean age. The non-dominant hand was involved in 67% of cases.

On coronal plane, the most common fracture type was typical transverse, seen in 56% of patients followed by medial oblique (20%), lateral oblique (14%), and high transverse (10%). In the sagittal plane, low sagittal (62%) was more common than high sagittal. Considering the fracture pattern in both the coronal and sagittal plane, typical transverse with low sagittal was the commonest type. Table 1 shows the distribution of incidence of fracture types in our study compared to the study by Bahk et al. The pin configuration was followed according to the fracture classification. 2 lateral pins configuration was the most common pin configuration. Table 2 shows the distribution of pin configuration as per Bahk classification in our study The mean period of fracture union was 43 days.

Table 1.

Incidence of fracture types in our study compared to the study by Bahk et al

| Fracture type | Incidence (our study) % | Incidence (Bahk et al.) % |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Transverse | 56 | 48.8 |

| Lateral Oblique | 14 | 43.8 |

| Medial Oblique | 20 | 3.9 |

| High Transverse | 10 | 3.4 |

| Low Sagittal | 62 | 60.6 |

| High Sagittal | 38 | 39.4 |

Table 2.

Distribution of pin configuration as per Bahk classification in our study(N = 100).

| Bahk Classification | No. | 1 Lateral +1 Medial | 2 Lateral | 2 Lateral +1 Medial | 3 Lateral |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Transverse | 6 | 4 | 2 | ||

| High Sagittal | |||||

| High Transverse | 4 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Low Sagittal | |||||

| Lateral Oblique | 8 | 8 | |||

| High Sagittal | |||||

| Lateral Oblique | 6 | 6 | 0 | ||

| Low Sagittal | |||||

| Medial Oblique | 8 | 8 | |||

| High Sagittal | |||||

| Medial Oblique | 12 | 12 | |||

| Low Sagittal | |||||

| Typical Transverse | 16 | 12 | 4 | ||

| High Sagittal | |||||

| Typical Transverse | 40 | 40 | 0 | ||

| Low Sagittal | |||||

| Total | 100 | 12 | 46 | 35 | 7 |

97% of the fractures were managed by closed reduction. Out of three patients undergoing open reduction two had associated vascular injuries with absent radial pulse and delayed capillary refill time which was confirmed by CT angiography and needed a vascular surgeon’s intervention. In one another patient open reduction was done as closed reduction methods failed to achieve reduction, due to soft tissue interposition.

One patient developed postoperative pin tract infection and loosening with loss of reduction and required revision surgery. The infection was controlled with intravenous antibiotics and the fracture united subsequently.

We obtained excellent results in 93% of patients, good in 5%, and fair in 2% patients as per modified Flynn’s criteria. The patients with not ‘excellent’ Flynn’s criteria had more affection of range of motion than the loss of carrying angle. Out of the two patients with fair results, one patient had undergone revision surgery for pin loosening secondary to infection and the second one had undergone vascular surgical intervention in index surgery.

At the last follow-up, the mean Baumann’s angle was 73.65 ± 5.60, compared to 73.77 on the normal uninjured side. Paired T test was performed with a P value of 0.937 which indicated that it was ‘Not Significant’.

68% of the patients had the anterior humeral line passing through the middle third of the capitelum followed by 27% through the anterior third and 5% through the posterior one-third of the capitelum. None of the patients had anterior humeral line passing grossly anterior or posterior to the capitelum.

Preoperative anterior interosseous nerve palsy was noted in 3 patients but all of them recovered postoperatively within a mean period of 23 days. Postoperative ulnar nerve palsy was seen only in 1 out of the total 100 patients (that is in 1 out of the 47 patients undergoing medial pinning), the patient recovered within 3 months of surgery.

4. Discussion

Supracondylar humerus fractures constitute 58% of the fractures in children.9,12 Gartland classification based on the degree of displacement of fracture fragments is the most widely used classification guiding treatment10,11. Another classification described by Bahk et al. describes different fracture patterns and analyses their possible effects on treatment or outcome.3 To the best of our knowledge, there is no prospective study to validate observations made by Bahk classification. We present the results of a prospective study of supracondylar humerus fractures in children which were managed as per recommendations by Bahk classification.

Till date surgeons have used multiple pin configurations as deemed necessary by them intraoperatively to make fracture construct stable.3 Biomechanical studies in the literature suggest cross pin configuration is more stable than any other configurations.13 But medial pin has a 1%–6% risk of iatrogenic ulnar nerve palsy.2 Few studies have found comparing results between cross pin configuration and two lateral pin configuration,14, 15, 16, 17 while Skaggs et al. suggested the use of three lateral divergent pins to make the construct stable.15 Whatever may be the construct, the ultimate goal should be to make it biomechanically stable.

Bahk et al. in their retrospective study in 2008 identified a few fracture patterns and made recommendations specific to them. In high transverse fractures, where the fracture line is near and above the olecranon fossa, less bone surface area is available in proximal bony fragment for pin purchase. If two lateral pin configuration is used for such type of fractures, both the pins will have a purchase in a small area of proximal bone near the fracture line, making the construct biomechanically unstable. On the contrary, cross pin configuration will have a purchase in different areas of proximal bone, making it biomechanically stable. In medial oblique fractures, where the fracture line starts at the lateral epicondyle and exists proximally medially, less bone surface is available in the lateral condyle. If two lateral pin configuration is used for such fractures, the proximal pin may have minimal fixation because of the obliquity of fracture, making the construct biomechanically unstable. Hence in such fractures, a medial pin is necessary.3 Therefore, identifying such fracture patterns and restricting the use of a medial pin only when it is necessary, will be a good strategy.

Bahk et al. observed supracondylar fractures with increased coronal (>10°) and sagittal (>20°) obliquity were more unstable, more comminuted, and were prone to rotational malunions. They had identified malrotation (discrepancy ≥ 20% width on lateral radiograph) of around 34% in their series.3 In our series, we have found a malrotation percentage of 10% which is significantly less than their observation. There may be multiple factors contributing to this. Since ours is a prospective study, preoperative recognition of fracture patterns and the use of suitable pin configuration for the fracture type may be one of them.

In our study, we evaluated the functional outcome of supracondylar humerus fractures by modified Flynn’s criteria, which primarily takes range of movement at the elbow and carrying angle into consideration.8 In comparison with previous studies, involving operative management of supracondylar humerus with percutaneous pinning, our study has favorable outcomes8,17,18,19. We have got excellent results in 93% of cases, a good outcome in 5%, and fair outcome in 2% of the cases; no poor outcome was recorded in our study.

Baumann’s angle in our series at union did not show a statistically significant difference compared to that of the opposite (normal) side.14,16,17 Cubitus varus deformity did not develop in any of our patients, consistent with studies by Boyd et al.20

There are a few limitations to our study. First, even though fixed protocols were there in place, multiple surgeons were involved in decision making and surgery which may add confounding variables in result interpretations. Second, there was no control group included in our study to compare the results.

5. Conclusions

Using pin configuration suitable to fracture pattern as per Bahk classification improve functional and radiological outcomes in supracondylar humerus fractures in children and minimizes complications.

Contribution

Dr.Santosh Banshelkikar: Concept, Investigation.

Dr.Binoti Sheth: Supervision; Validation.

Dr. Subhashis Banerjee: Data curation; Writing - review & editing.

Dr. Mohammad Maaz: Data collection.

Funding

Not received any fundings.

Declaration of competing interest

No author has any conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Santosh Banshelkikar, Email: drsantoshnb@gmail.com.

Binoti Sheth, Email: binotisheth@gmail.com.

Subhashis Banerjee, Email: subhashisbsmc@gmail.com.

Mohammad Maaz, Email: mdmaaz89@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Holmberg L. Fractures in the distal end of humerus in children. Acta Chir Scand. 1945;92:5–55. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brauer C.A., Lee B.M., Bae D.S. A systemic review of medial and lateral entry pinning versus lateral entry pinning for supracondylar fractures of the humerus. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:181–186. doi: 10.1097/bpo.0b013e3180316cf1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahk M.S., Srikumaran U., Ain M.C. Patterns of pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28:493–499. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31817bb860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blount W.P. Supracondylar (diacondylar , transcondylar) fractures. In: Wilkins W., editor. Fractures in Children. 1955. pp. 26–42. Baltimore. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyons J.P., Ashley E., Hoffer M.M. Ulnar nerve palsies after percutaneous cross pinning of supracondylar fractures in children’s elbow. J Paediatr Orthop. 1998;18:43–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edmonds E.W., Roocroft J.H., Mubarak S.J. Treatment of pediatric supracondylar fracture pattern requiring medial fixation: a reliable and safer cross pinning technique. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32:346–351. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318255e3b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bombaci H., Gereli A., Kucukyazici O. A new technique of crossed pins in supracondylar elbow fractures in children. Orthopedics. 2005;28:1405–1409. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20051201-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flynn J.C., Matthews J.G., Benoit R.L. Blind pinning of displaced supracondylar fracture of the humerus in children: sixteen years’ experience with long term follow up. J Bone Joint Surg. 1974;56:263–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Houshian S., Mehdi B., Larsen M.S. The epidemiology of elbow fractures in children: analysis of 355 fractures, with special reference to supracondylar humerus fractures. J Orthop Sci. 2001;6:312–315. doi: 10.1007/s007760100024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gartland J.J. Management of supracondylar fracture of humerus in children. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1959;109:145–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkins K.E., King R.E. Fractures in children. In: Rockwood C.A., editor. Fractures and Dislocations of the Elbow Region. third ed. JB Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1991. pp. 526–617. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houshian S., Mehdi B., Larsen M.S. The epidemiology of elbow fractures in children: analysis of 355 fractures, with special reference to supracondylar humerus fractures. J Orthop Sci. 2001;6:312–315. doi: 10.1007/s007760100024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zoints L.E., McKellop H.A., Hathaway R. Torsional strength of pin configurations used to fix supracondylar fractures of humerus in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:253–256. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199402000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kocher M.S., Kasser J.R., Waters P.M. Lateral entry compared with medial and lateral entry pin fixation for completely displaced fractures in children. A randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:706–712. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skaggs D.L., Hale J.M., Basset J., Kaminsky C., Ray R.M., Tolo V.T. Operative treatment of supracondylar fracture of the humerus in children: the consequences of pin placement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-a:735–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li M., Xu J., Hu T., Zhang M., Li F. Surgical management of type III supracondylar humerus fractures in older children: a retrospective study. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2019;28:530–535. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0000000000000582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mura M., Singh S., Wani M. Displaced supracondylar humerus fractures in children: treatment outcome following closed reduction and percutaneous pinning. J Orthop Surg. 2009;17:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webb A.J., Sherman F.C. Supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1989 May-June;9(3):315–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehserle W.L., Meehan P.L. Treatment of the displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus (Type III) with closed reduction and percutaneous cross-pin fixation. J Pediatr Orthop. 1991 Nov-Dec;11(6):705–711. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199111000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyd D.W., Aronson D.D. Supracondylar fractures of the humerus: a prospective study of percutaneous pinning. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992 Nov- Dec;12(6):789–794. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199211000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]