Abstract

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) usually provides good pain relief and improved function but has generally been unable to fully restore normal knee kinematics. Does Medial or Lateral Pivot TKA designs guide us to native knee kinematics needs to be elucidated?

Methods

Kinematic assessment of 13 knees with Medial Pivot TKA and 13 knees with Lateral Pivot TKA was done. The subjects were asked to perform step-up and weight bearing deep knee bend exercise under fluoroscopy for kinematic assessment. Patellar Tendon Angle (PTA) was measured after correcting f luoroscopic images for distortion against Knee Flexion Angle (KFA).

Results

During the weight bearing deep knee bend, the average active maximum flexion achieved with Medial Pivot design was 113.8 ͦ as compared to 102.9 ͦ with Lateral Pivot design. There was no significant difference in PTA in step up and deep knee bend exercise between both the designs.

Conclusion

The kinematic assessment of both the Medial and Lateral Pivot TKA designs revealed linear trend of PTA with increasing KFA as described for normal knee. Both the designs were able to achieve functional knee range of motion.

Keywords: Constraint, Medial pivot, Lateral pivot, Kinematics

1. Introduction

There has been constant debate regarding restoration of native knee kinematics post Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA). This is particularly relevant when patients attempt to perform high demand activities using their knee joint. The consequences of traditional TKA designs failure to reproduce physiologic medial pivot as well as posterior femoral roll back may contribute to patient dissatisfaction.1,30, 31, 32, 33, 34

A lot more understanding of complex knee kinematics has been available since 2008 with different pivoting motions with various range of knee flexion. In ACL-intact native knee, there appears to be lateral pivot motion at early flexion movements with medial pivot motion occurring at deeper flexion.2, 3, 4 With regard to knee kinematics, no implant has been able to provide superior patient outcomes.

Medial Pivot (MP) TKA prosthesis uses asymmetric tibial polyethylene inserts with a highly congruent medial side and a less conforming lateral compartment to limit anterior-posterior translation in the medial compartment while allowing femoral roll back in the lateral compartment.5 Its minimal anterior-posterior translation enhances quadriceps power and greater leverage for extensor mechanism is maintained.6 Unlike Medial Pivot, Lateral Pivot prosthesis polyethylene insert has more conformity on its lateral side with a relatively more shallow medial concavity on the tibial articular surface.7 Lateral condyle is stabilized by concave lateral insert which also centralizes the femur in extension, and thus leads to posterior lateral translations with deeper flexion irrespective of PCL status.7

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that no significant kinematic differences are present between Medial Pivot (MP) and Lateral Pivot (LP) Prosthesis.

2. Methods

A total of 13 patients who underwent bilateral simultaneous posterior cruciate ligament sacrificing TKA in our Institute with a minimum of 6 months follow up were recruited from the prospective study after obtaining Institute Ethical Clearance. Patients had randomly received MP Prosthesis (ADVANCE® Medial Pivot, Micro Port Orthopedics, and Arlington, TN, USA) on one side and a LP Prosthesis (EMPOWR 3D Knee® system; DJO Global, Inc; Vista, CA) in contralateral knee in a randomized manner. Patella was not resurfaced.

2.1. Kinematic profile

Kinematic assessment was done post-operatively at 6 months. Each subject was asked to perform a single step up exercise and a weight bearing deep knee bend exercise for each of their knees.1 For the step-up exercise, the foot of the examined limb was positioned on an adjustable platform around 250 mm high to produce an approximate flexion of 80° in the desired knee while the other foot rested on the ground.1,8, 9, 10 Patients were instructed to rise as if progressing up a step of stairs. For the deep knee bend exercise, subjects lowered themselves towards the floor from a standing position by flexing the supported knee; this produced a flexion of 100° in the examined knee. These exercises represent daily functional activities of the patients. Fluoroscopy images were recorded in the sagittal plane of the knee as each exercise was performed. Images were sampled at 25 frames per second to allow the knee to remain in the fluoroscopy field for the duration of the exercise. A parallel calibration object was placed and its image was taken. This allowed image to be corrected for distortion using a global correction method.11,12 This was done using MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA), version 7.10.0.499 (R2010a) and DICOM format was used to digitally record the image. TIFF format was used to give a single sequence of images. The clearest images were selected for analysis.

A graphical interface was used to determine the femoral and tibial axes, the tibial tubercle, and the distal pole of the patella in each frame of recorded functional activity. The femoral long axis and tibial long axis are defined as the posterior border of the lower diaphysis of the femur and the posterior border of tibia respectively13,14,. The angle between the femoral long axis and tibial long axis was taken as Knee Flexion Angle (KFA). Patellar Tendon Angle (PTA) was calculated using the line subtended between the tibial tubercle and the distal pole of the patella, and, tibial axis. PTA was calculated at every 10° of KFA throughout the flexion range. The relationship between PTA and KFA was analyzed using MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA), version 7.10.0.499 (R2010a).

2.2. Inter-observer correlation

The interclass correlation coefficient15 was good to excellent for kinematic evaluation.

2.3. Statistical analysis

PTA was analyzed between the groups using Student’s t-test for independent samples and within the group using paired t-test/Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Mann-Whitney U test) as applicable. Kinematic analysis was done with two independent observers. All analyses were conducted using Stata 12.0 (Stata Corp LLC, Texas, and USA). A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

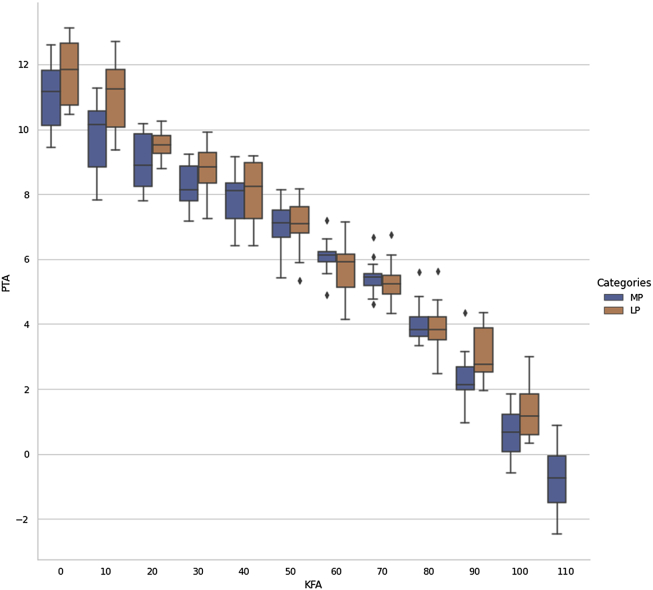

The average maximum weight bearing flexion achieved for the MP knee was 113.8 ± 3.8 ͦ as opposed to 102.9 ± 2.9 ͦ in LP knee which was statistically significant (p < 0.05). The mean PTA of the LP group was 1.31 ͦ (S.D 0.8 ͦ) at 100 ͦ of KFA which increased to 11.76ͦ (S.D 0.95 ͦ). The mean PTA of the MP group was at 0.62 ͦ (S.D 0.85 ͦ) 100 ͦ of KFA which increased to 11.03 ͦ (S.D 1.0 ͦ). (Fig. 1) (Table 1, Table 2).There was no significant difference in PTA/KFA between both the groups from 0 to 100 ͦ of KFA. The trend observed in PTA from full extension to maximum flexion was linear (Fig. 2). During extension, the PTA is positive and with flexion, it decreases (Fig. 3a–b).

Fig. 1.

PTA values of MP and LP Prosthesis with increasing KFA.

Table 1.

Descriptive value of patients PTA with Medial Pivot design with every 10 ͦ of KFA.

| S No/KFA | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11.82 | 10.55 | 10.18 | 9.22 | 8.17 | 8.14 | 7.19 | 6.68 | 5.61 | 4.35 | 1.21 |

| 2 | 11.55 | 10.26 | 9.74 | 9.14 | 9.15 | 7.93 | 6.62 | 6.07 | 4.41 | 3.15 | 1.79 |

| 3 | 9.79 | 8.19 | 7.8 | 7.45 | 6.41 | 5.84 | 6.11 | 4.78 | 3.75 | 2.17 | 0.89 |

| 4 | 10.12 | 8.83 | 8.9 | 7.17 | 7.24 | 6.67 | 6.14 | 5.19 | 3.82 | 2.53 | 1.84 |

| 5 | 11.46 | 10.14 | 8.5 | 8.87 | 8.41 | 7.51 | 6.16 | 5.45 | 3.42 | 1.98 | 0.34 |

| 6 | 12.61 | 11.27 | 9.86 | 8.45 | 8.34 | 7.11 | 5.93 | 5.51 | 3.62 | 2.04 | −0.59 |

| 7 | 10.67 | 9.64 | 8.87 | 8.13 | 7.56 | 7.08 | 6.13 | 5.43 | 3.88 | 1.96 | 0.17 |

| 8 | 12.14 | 10.73 | 9.97 | 9.14 | 8.91 | 7.82 | 6.24 | 5.84 | 4.23 | 2.77 | 1.54 |

| 9 | 9.99 | 8.84 | 8.06 | 7.26 | 7.26 | 6.13 | 5.54 | 4.92 | 3.98 | 2.67 | 1.11 |

| 10 | 9.45 | 7.83 | 8.14 | 7.87 | 6.75 | 5.41 | 4.89 | 4.61 | 3.61 | 0.97 | −0.54 |

| 11 | 11.17 | 10.22 | 9.19 | 8.4 | 8.14 | 7.12 | 6.07 | 5.54 | 3.65 | 1.68 | 0.07 |

| 12 | 12.04 | 10.64 | 10.01 | 8.12 | 8.12 | 6.94 | 5.87 | 5.51 | 3.34 | 2.11 | 0.67 |

| 13 | 10.55 | 9.61 | 8.23 | 7.79 | 7.79 | 7.14 | 6.27 | 5.38 | 4.84 | 2.14 | −0.39 |

Table 2.

Descriptive value of patients PTA with Lateral Pivot design with every 10 ͦof KFA.

| S No/KFA | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12.7 | 11.84 | 9.52 | 9.15 | 8.17 | 8.16 | 7.14 | 6.74 | 5.64 | 4.34 | 2.99 |

| 2 | 11.57 | 11.58 | 10.26 | 9.79 | 9.15 | 7.89 | 6.56 | 6.13 | 4.43 | 4.11 | 1.81 |

| 3 | 10.53 | 9.81 | 9.15 | 7.77 | 6.41 | 5.89 | 5.14 | 4.76 | 4.75 | 3.89 | 1.95 |

| 4 | 11.63 | 10.02 | 8.88 | 8.8 | 7.24 | 6.81 | 5.84 | 5.19 | 3.52 | 2.53 | 1.84 |

| 5 | 12.98 | 11.45 | 10.19 | 9.6 | 8.41 | 7.61 | 6.16 | 5.45 | 3.42 | 2.54 | 0.34 |

| 6 | 12.64 | 12.71 | 9.25 | 9.9 | 8.34 | 7.08 | 5.93 | 5.46 | 3.62 | 3.51 | 0.59 |

| 7 | 11.84 | 10.54 | 9.61 | 8.75 | 7.56 | 7.18 | 6.13 | 4.33 | 3.74 | 1.96 | 1.17 |

| 8 | 11.83 | 12.04 | 9.72 | 8.85 | 8.91 | 7.72 | 6.24 | 5.69 | 4.23 | 2.77 | 1.54 |

| 9 | 10.45 | 10.07 | 9.81 | 7.94 | 7.26 | 6.11 | 4.89 | 4.92 | 3.98 | 2.67 | 1.11 |

| 10 | 10.61 | 9.36 | 8.79 | 7.25 | 6.75 | 5.35 | 4.13 | 4.45 | 2.47 | 2.87 | 0.54 |

| 11 | 12.28 | 11.25 | 10.01 | 9.29 | 8.14 | 7.02 | 6.07 | 5.51 | 3.51 | 2.44 | 2.07 |

| 12 | 13.13 | 12.1 | 9.51 | 9.12 | 8.12 | 6.84 | 5.15 | 5.24 | 3.88 | 2.11 | 0.67 |

| 13 | 10.75 | 10.6 | 9.41 | 8.35 | 7.79 | 7.25 | 5.11 | 5.11 | 3.84 | 3.89 | 0.39 |

Fig. 2.

PTA/KFA graph between MP and LP Prosthesis showing linear trend.

Fig. 3.

a & b: PTA and KFA in Knee flexion and Knee extension.

4. Discussion

The aim of the current study was to identify whether medial or lateral pivot TKA designs restores normal knee kinematics. It has been seen that there are several different kinematic behaviors’ between replaced knee and the normal knee.17

In this current study, there was no significant difference observed in 0–100 ͦ range of KFA between both the types of prosthesis throughout the range of motion and PTA was linear throughout this arc of motion similar to the one described for the normal knee.1 The change in trend of PTA between both designs in mid-flexion range of motion, although not significant, could be attributed to multi-radius design of femoral component of LP in which there is abrupt transition of larger radius anterior to smaller radius posterior.24

The PTA/KFA provides complete overview of knee joint kinematics as it involves both the tibio-femoral and the patella-femoral joints.10,17, 18, 19 The knee kinematic activity involved standing from a sitting position; a routine daily activity and which requires good amount of mid flexion stability and it is well established with deep weight bearing flexion activities.25 The kinematic activity reflects intact functional extensor mechanism apparatus. Dynamic radiographs had been used to measure tibio-femoral contact points for a range of activities involving deep flexion and reproduced with a result of medial central of rotation.20, 21, 22, 23 There is discordance in two of the studies which had not shown medial centre of rotation during stair ascent in near full extension.20,23 Since the modern understanding of knee kinematics in ACL-intact native knee, there appears to be lateral pivot motion at early flexion movements with medial pivot occurring at deeper flexion and this activity would ensure higher patient satisfaction.2−4These recent studies suggest that the knee kinematics is very different during ambulatory activities with the knee in extension.

The higher PTA value seen with LP prosthesis with knee in full extension in our study could be attributed to the lateral constraint of the polyethylene design which counteracts the small amount of lateral laxity usually seen after TKA done in varus osteoarthritic knees; thus making the knee stable in early flexion activities such as running and impact sports.24

Higher KFA (>110 ͦ) was seen with the MP-TKA which can be attributed to its femoral component design of single radius curvature providing biomechanical advantage to quadriceps strength by increasing the patellar tendon moment arm and decreasing the patellar tendon angle with increasing flexion.16 This finding is statistically significant but must be interpreted with caution considering the small number of patients involved in the study and the improvement in functional knee of range of motion that can happen till 1 year after surgery.

The authors chose to draw a comparison between these two types of designs as both of them are fixed bearing pivoting asymmetric tibio-femoral articulation designs with good to excellent clinical outcome data. It has been seen that well controlled kinematics lead to better bearing wear performance, greater functional strength and more normal muscle coordination.26, 27, 28, 29

The major limitation of the study is that only 2D model was studied and no clinical and functional outcomes of patients were correlated. 3D model could have given us details about the anterior-posterior movement of the condyles with the flexion movement. Other limitations are the small subset of patients, single centre study, absence of blinding and no comparison was made with the normal knee kinematics. The surface geometry of TKR design and posterior slope of tibial component, both of which can alter PTA were not studied.

To conclude the results of our study involving the kinematic assessment of both the medial and lateral constraints revealed linear trend of PTA with increasing KFA as described for normal knee. Both the designs were able to achieve functional knee range of motion.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Contributor Information

Sahil Batra, Email: sahilbatra25@gmail.com.

Pon Aravindhan A. Sugumar, Email: madhan.ponra@gmail.com.

Vijay Kumar, Email: vijayaiims@yahoo.com.

Rajesh Malhotra, Email: rmalhotra62@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Duren V., Pandit H., Beard D.J. How effective are constraints in improving TKR kinematics. J Biomech. 2007;(40):831–837. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koo S., Andriachi T.P. The knee joint centre of rotation is predominantly on the lateral side during normal walking. J Biomech. 2008;41(6) doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.01.013. 1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamaguchi S., Gamada K., Sasho T., Kato H., Sonoda M., Banks S.A. In vivo kinematics of anterior cruciate ligament deficient knees during pivot and squat activities. Clin Biomech. 2009;24(1):71. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meneghini R.M., Deckard E.R., Ishmael M.K., Davis Ziemba. A dual- pivot pattern simulating native knee kinematics optimizes functional outcomes after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman M.A., Pinskerova V. The movement of the normal tibiofemoral joint. J Biomech. 2005;38:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt Robert, Komistek Richard D., Blaha J., David Penenberg, Brad L., Maloney William. Journal of clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2003;410:139–147. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000063565.90853.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe T., Ishizuki M., Muneta T., Banks S.A. Knee kinematics in ACL substituting arthroplasty with or without the PCL. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:548–552. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Duren B.H., Pandit H., Price M. Bicruciate substituting total knee replacement: how effective are the added kinematic constraints in vivo? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. Oct 2012;20(10):2002–2010. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1796-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monk A.P., van Duren B.H., Pandit H., Shakespeare D., Murray D.W., Gill H.S. In vivo sagittal plane kinematics of the FPV patellofemoral replacement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:1104–1109. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1717-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandit H., van Duren B.H., Gallagher J.A. Combined anterior cruciate reconstruction and oxford unicompartmental knee 386 arthroplasty: in vivo kinematics. Knee. 2008;15:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baltzopoulos V. A video fluoroscopy method for optical distortion correction and measurement of knee-joint kinematics. Clin Biomech. 1995;10:85–92. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(95)92044-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Duren B.H., Pandit H., Beard D.J., Murray D.W., Gill H.S. Accuracy evaluation of fluoroscopy-based 2d and 3d pose reconstruction with unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Med Eng. Phys. 2009;31:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rees J.L., Price A.C., Beard D.J., Robinson B.J., Murray D.W. Defining the femoral axis on lateral knee fluoroscopy. Knee. 2002;9:65–68. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0160(01)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Eijden T.M., de Boer W., Weijs W.A. The orientation of the distal part of the quadriceps femoris muscle as a function of the knee flexion-extension angle. J Biomech. 1985;18:803–809. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(85)90055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koo T.K., Li M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropractic Med. 2016;15(2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward T.R., Pandit H., Hollinghurst D. Improved quadriceps’ mechanical advantage in single radius TKRs is not due to an increased patellar tendon moment arm. Knee. 2012;19:564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandit H., Ward T., Hollinghurst D. Influence of surface geometry and the cam-post mechanism on the kinematics of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87:940–945. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B7.15716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price A.J., Oppold P.T., Murray D.W., Zavatsky A.B. Simultaneous in vitro measurement of patellofemoral kinematics and forces following oxford medial unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:1591–1595. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B12.18306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rees J.L., Beard D.J., Price A.J. Real in vivo kinematic differences between mobile-bearing and fixed-bearing total knee arthroplasties. J. clinic. ortho. related res. 2005:204–209. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000150372.92398.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moro-oka T.A., Hamai S., Miura H. Dynamic activity dependence of in vivo normal knee kinematics. J Orthop Res. 2008;26(4):428–434. doi: 10.1002/jor.20488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamai S., Moro-oka T.A., Miura H. Knee kinematics in medial osteoarthritis during in vivo weight-bearing activities. J Orthop Res. 2009;27(12):1555–1561. doi: 10.1002/jor.20928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennis D.A., Mahfouz M.R., Komistek R.D., Hoff W. In vivo determination of normal and anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee kinematics. J Biomech. 2005;38(2):241–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li G., Moses J.M., Papannagari R., Pathare N.P., DeFrate L.E., Gill T.J. Anterior cruciate ligament deficiency alters the in vivo motion of the tibiofemoral cartilage contact points in both the anteroposterior and mediolateral directions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1826–1834. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banks S.A., Deckard E., Hodge W.A., Meneghini R.M. Rationale and results for fixed-bearing pivoting designs in total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2019;32(7):590–595. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1679924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.KOMISTEK R.D., DENNIS D.A., MAHFOUZ M. In vivo fluoroscopic analysis of the normal human knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;410:69–81. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000062384.79828.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Draganich L.F., Piotrowski G.A., Martell J., Pottenger L.A. The effects of early rollback in total knee arthroplasty on stair stepping. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17(6):723–730. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.33558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell K., Banks S., Rawlins J., Wood S., Hodge W. Strength of intrinsically stable TKA during stair-climbing. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 2005:563. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H., Simpson K.J., Ferrara M.S., Chamnongkich S., Kinsey T., Mahoney O.M. Biomechanical differences exhibited during sit-to stand between total knee arthroplasty designs of varying radii. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(8):1193–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.02.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blunn G.W., Walker P.S., Joshi A., Hardinge K. The dominance of cyclic sliding in producing wear in total knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;(273):253–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moonot P., Mu S., Railton G.T., Field R.E., Banks S.A. Tibiofemoral kinematic analysis of knee flexion for a medial pivot knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(8):927–934. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0777-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moonot P., Shang M., Railton G.T., Field R.E., Banks S.A. In vivo weight bearing kinematics with medial rotation knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2010;17(1):33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimmin A., Martinez-Martos S., Owens J., Iorgulescu A.D., Banks S. Fluoroscopic motion study confirming the stability of a medial pivot design total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2015;22(6):522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ginsel B.L., Banks S., Verdonschot N., Hodge W.A. Improvingmaximum flexion with a posterior cruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty: a fluoroscopic study. Acta Orthop Belg. 2009;75(6):801–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mikashima Y., Tomatsu T., Horikoshi M. In vivo deep-flexion kinematics in patients with posterior-cruciate retaining and anterior-cruciate substituting total knee arthroplasty. Clin Biomech. 2010;25(1):83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]