Abstract

Objective

Oswestry disability Index(ODI) is the commonest patient reported outcome for assessment of disability due to low back pain. Its application to non-English speaking Punjabi population is limited as a validated and cross culturally adapted Punjabi version of ODI is not available. The purpose of the study was to analyse the psychometric properties of Punjabi version of Oswestry disability index (ODI-P) in patients with mechanical low back pain.

Materials and methods

The translation and cross-cultural adaptation of Punjabi version of ODI was done according to well recommended guidelines. The prefinal version was tested on a set of 15 patients and suitable modifications were made. The final version was administered to 113 patients with mechanical low back pain of more than two weeks duration. Psychometric properties comprising of internal consistency, test retest reliability, floor and ceiling effect, construct validity and factorial structure of the questionnaire were determined.

Results

ODI-P showed excellent internal consistency (Chronbach alpha of ODI-P is 0.72), test retest reliability (ICC 0.891) and construct validity (Spearman correlation coefficient with VAS 0.424). Factor analysis proved the questionnaire to be having a 1-factor structure with a total variance of 48.61%.

Conclusions

ODI (P) is a reliable and valid instrument for measurement of disability related to mechanical low back pain in Punjabi population. It can be used both in research and clinical care settings in future.

Keywords: Mechanical low back pain, Cross-cultural adaptation, Oswestry disability index, Punjabi, Patient reported outcome measures

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Activity limiting low back pain (LBP) has been estimated to have a lifetime prevalence of approximately 39% and a similar annual prevalence of 38% with majority of the people having recurrent episodes.1 Similar figures are not available for India but lifetime risk has been reported to be around 60% of people having significant back pain some time in life.2 In more than half of the patients it is associated with persistent pain and disability which has significant impact on the quality of life of the patient.

The high epidemiological and clinical burden of LBP makes it paramount to apply validated and reliable outcome measures to assess outcomes quantitatively and to improve interventions for LBP.3 As compared to clinical evaluation alone, patient reported outcome measures better reflect the overall health status of the patient as they evaluate multiple interrelated domains of pain, disability, functional status and their impact on quality of life.4

There are approximately 40 self-reported outcome measures available for use in patients with back pain.5 An ideal measure should be one which has acceptable psychometric properties i.e. it is reliable, valid, reproducible and responsive across a spectrum of clinical care and research settings. It should be easy to administer and lend itself to relevant statistical analysis.6

Most of the measures in use have been developed for English speaking populations following Western lifestyle. As such they might not be applicable to all populations. Majority of the authors advocate the use of standardized measures instead of creating new tools and recommend cross cultural adaptation of validated questionnaires in regional languages.6 This is a simple and efficient way to compare outcomes across the world and also helps in pooling of the data for researchers.5 Cross cultural adaptation is necessary to maintain the content validity of the outcome measure at a conceptual level across different cultures.6. Further, psychometric properties for the adapted version after the translation need to be evaluated to exclude any discrepancy and maintain the integrity of the original questionnaire.5

Oswestry Disability Index(ODI) is the most used and validated outcome measure for evaluation of low back pain.7 ODI has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties in a wide variety of clinical care and research settings.8 After its introduction, the original questionnaire has been upgraded several times and the current version recommended for use is 2.1a.9 The questionnaire is completed in about 5 min and scored in less than 1 min10 The ODI has already been translated and validated in many languages like German, Arabic, Chinese, Korean, Danish, Greek, etc.11 ODI has been translated into 4 Indian languages i.e. Hindi, Tamil, Kannada and Marathi.2,12, 13, 14,This has provided standardized data and allowed comparison of outcomes and pooling of data across different populations and countries.

Punjabi has more than 30 million native speakers in India and more than 100 million worldwide, making it the 11th most widely spoken language worldwide. Further Punjabi is the language of a large community having a rich diaspora which is spread in India and worldwide. No current validated Punjabi versions of ODI exists as of now. In a country like India with its diversity of languages and cultures and internal migration, it is all the more important to have validated version of ODIs in Indian languages which can be used for evaluation and comparison of results across different populations.

The aim of this study is to test the psychometric properties of ODI-P (Punjabi version) developed using well defined and accepted protocol on the patients presenting with mechanical low back pain.

2. Material and methods

128 adult patients aged 18–60 years of lowback pain of more than 2 weeks duration presenting to outpatient clinic were included in the study. Only the patients with the ability to read and write Punjabi fluently were included. Patients with acute low back pain, recent thoracolumbar trauma, tumors, spinal deformity, spondylodiscitis, inflammatory disease or previous spine surgery were excluded. Lactating mothers, pregnant ladies and patients with neurologic deficits, systemic illness, psychiatric and mental deficits and any other significant comorbidity were also excluded. The permission to adapt ODI version 2.1a to Punjabi version was taken from the copyright holders. The study was approved by institutional ethics committee and all the patients were voluntary informed participants.

2.1. The study involved two phases

-

i.

The translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the original English version of ODI into Punjabi version ODI–P. This was carried out in accordance with recommendations of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons as described in detail by Beaton et al.6(Fig. 1)

Step 1

Forward Translation. Two translations of ODI were performed independently. One of the translators was a professional translator with no medical background and one translator was a medical personal who had knowledge of these questionnaires and who was well conversant with reading and writing Punjabi. A single questionnaire was generated after reaching a consensus between the two translators.

Step 2

Backward Translation This final version was then translated back to English language by two professional translators who did not have a medical background.

Step3

Expert Committee. The translated versions were then reviewed by an expert committee consisting of clinical experts as well as all the 4 translators to identify difficulties, inconsistencies and mistakes in translation as well as conceptual equivalence of items and answers. After all the members reached unanimity a pre final version of ODI-P was created.

Step 4

Test of the Pre-final Version. - The questionnaire thus developed was administered to 15 patients with LBP. This was done to test the understanding of the respondents of each item of the questionnaire. All the findings from this step were re-evaluated by the expert committee, and all the required adjustments were made.

- ii.

Psychometric analysis of the developed version of ODI: ODI-P

The final version thus achieved was administered to patients and the time needed for reporting was also noted. The patients were asked to fill another version after 4–7 days of filling the questionnaire for the first time. Visual Analogue Score (VAS) was also measured at the time of administration of each of the questionnaires. 113 patients completed the final questionnaire and these were subjected to a detailed psychometric analysis. In case of a missing response, the whole score was divided by 9 instead of 10 to achieve final ODI score. The score thus achieved was multiplied by 2 to get a percent disability ODI-P score out of 100.

Floor/ceiling effects were defined as the presence of lowest or highest possible total score in more than 15% of respondents.In this study, the reliability of ODI-P has been calculated by using the internal consistency method and the test –retest reliability method. Internal consistency method or the Chronbach alpha is based on the number of items in a scale and the homogeneity of the items. A value between 0.7 and 0.9 denotes adequate internal consistency. In our study we calculated this reliability by repeating the questionnaire after 4–7 days.This is measured by intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and ICCs can vary from 0.00 to 1.00, where values of 0.60–0.80 are regarded as evidence of good reliability and with those above 0.80 indicating excellent reliability. We compared the questionnaire with VAS which is an external measure which can also reflect back pain. Validity coefficients were accepted as follows: 0.81–1.0 as excellent, 0.61–0.80 very good, 0.41–0.60 good, 0.21–0.40 fair, and 0–0.20 poor. Factors structures were assessed using a Varimax rotation exploratory factor analysis to determine the number of extracted factors with eigenvalues more than 1.Varimax rotation was applied, and items with a factor loading of more than 0.40 were included in the factor.

Fig. 1.

Process of development of ODI-P and its psychometric analysis.

2.2. Observations and results

15 of the 128 patients went through the pre-final version of the translated ODI as pilot cases. Of the remaining 113 patients were enrolled in for analysis of the psychometric properties of the questionnaire. The average age was 39 years. The socio-demographic characters of the population are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Showing socio-demographic characters of the population.

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 38 | 33 |

| Female | 76 | 67 |

| Employed | 56 | 49 |

| Education: >10th <10th |

94 20 |

82 18 |

| Duration of pain >14 days to 1 month 1 month to 3months >3 months |

31 40 43 |

27 35 38 |

After testing on a pilot population comprising of 15 patients, various transformations were done to make it more familiar for the population being tested. The phrase ‘washing and dressing’ was changed to ‘bathing and washing’ to make it sound more idiomatically suitable in the vernacular language. Every option was made more fitting for both the genders by ending it dichotomously. The units of distance ‘meter’ and ‘kilometers ‘were retained as they were more familiar with the population. The word ‘toilet’ was also retained for similar reasons and there were no complaints regarding difficulties in understanding the word.

Acceptability:The questions were well accepted and understood by the patients. The question 8 regarding the sex life was left by 17(15%) patients during first time and by 15(13%) during their next attempt. There was no problem regarding the comprehension and understanding the various items. All the questions were attempted in 4–10 min with average time of 5 min without help.

Floor and ceiling effects: The ODI –P had no floor/ceiling effects as no patient reported minimum or maximum scores. The distribution of ODI-P scores is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of ODI-P.

Internal Consistency:The Internal consistency of ODI was calculated by using the Chronbach alpha which came out to be 0.722.

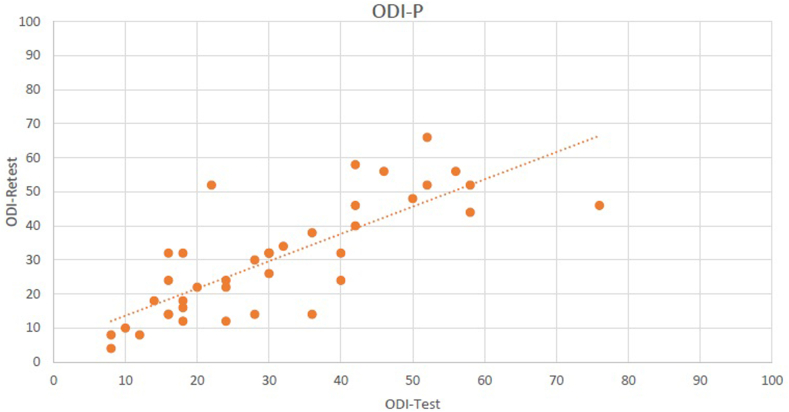

Test-retest reliability::41 out of 113 patients completed retest evaluation which was done after 4–7 days of first evaluation(Fig. 3). Only the patients who had similar VAS and were able to complete the retest were included. The test retest reliability in them came out to be 0.891 (0.795-0.942), which is an excellent result.

Fig. 3.

Relationship between test and retest scores of ODI-P.

Validity:Concurrent Validity is implemented to ascertain the degree to which the tested instrument relates to other established instruments to assess whether conceptual definitions match the operational definitions. The value of construct validity between ODI-P and VAS came out to be 0.424 which is considered to be good.

Factor Analysis:Factor analysis is a measure to determine the dimensionality of the items of a questionnaire i.e. it determines the number of dimensions it forms, whether 1 or more than 1 over all dimension. In our study we analyzed the principal component factor analysis with varimax rotation. The optimum number of factors were determined by eigen values of more than 1 and an item loading of each component of 0.4 or more was considered to be satisfactory. A single factor structure was established of ODI-P as described by eigen values of 4.861 providing a variance of 48.61% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Showing factorial structure of ODI-P.

|

Items |

Component |

|---|---|

| 1 | |

| Pain | .525 |

| Personnel Care | .692 |

| Lifting | .734 |

| Walking | .597 |

| Sitting | .731 |

| Standing | .738 |

| Sleeping | .769 |

| Sex Life | .700 |

| Social Life | .765 |

| Travelling | .754 |

3. Discussion

The aim of our study was to develop and cross culturally adapt and validate the Oswestry Disability Index for the Punjabi speaking population.

Although ODI has been translated to many Indian languages including Hindi which is spoken and understood by a majority of population but there are vast socio cultural differences among people who are separated by regional and linguistic barriers, Punjabi speaking population forming one such group. Punjabi as a language has a unique dialect, expressions, language structures, nuances and technicalities thus other ODIs are not understood and accepted correctly by Punjabi speaking population. Even though they understand Hindi, most of the patients from rural and semi urban Punjab are unable to read and write Hindi and hence unable to self report the ODI. Likewise, different ODI versions in simplified Chinese and traditional Chinese have been developed in spite of them being different representations of essentially the same language; one being a refined version of other.15,16

All participants answered and there was no problem in interpretability. The question regarding sex life was left unmarked by 16% of patients during the first test and by 13% during the second test. It was interesting to note that this question was accepted by the majority in spite of the fact that Punjabis belonged to a conservative society. It was found to be inappropriate by 13% of the participants in German study while 19% of Iranians left the question ananswered.17 This item of the questionnaire has caused issues in some cultures and some versions of ODI have omitted this question.9 This question was omitted in the Korean version as it was answered by only 42% of participants.18,19 We have kept this question as optional for the respondent in stem statement as has been recommended by the original developers of the ODI.

Internal consistency method or the Chronbach alpha is based on the number of items in a scale and the homogeneity of the items. The values recommended to determine adequate internal consistency are 0.7–0.9. The Chronbach alpha of ODI-P was 0.722 indicating excellent internal consistency. This is almost similar to Iranian version which had a Chronbach alpha of 0.75. Our value was however found to be less than the Hindi (0.99), Marathi(0.943) and Tamil(0.92)versions.2,12,13 A very high value of Chronbach alpha will indicate that some items will be redundant on the questionnaire.5On the other hand a low value (<0.7) will indicate that all the items in questionnaire are not addressing the same underlying dimension which is low back pain related disability in ODI.

The ODI-P did not have a floor or ceiling effect as less than 15% of patients had either minimum or maximum possible scores. The presence of floor and ceiling effect limits the content validity and reliability of the outcome measure. Presence of these effects indicate that extreme items are missing and patients falling at the ends of score cannot be distinguished from each other.20This makes it possible to miss deterioration or improvement for patients lying at the ends of the scale.5,20 Similarly to our study, ODI has been shown not to have floor and ceiling effect in almost all studies except for studies on Finnish and German population where the floor effect was found in 18.6% and 20% of subjects.18,21

Test retest reliability is defined as the degree of assessment which yields similar results at two different occasions in absence of intervening effects such as memory recall or improvement due to treatment. For testing the test-retest reliability of ODI-P intraclass correlation coefficient was measured which came out to be 0.891. ICCs can vary from 0.00 to 1.00 whereas values of 0.60–0.80 show good reliability whereas those having more than 0.80 value indicate excellent reliability. It was tested on patients who had not shown change in VAS score on fourth to seventh day even after following the treatment advice given by us according to protocol on OPD basis. An early retest would skew the results due to the memory effect thus falsely indicating high test retest reliability.8 If done later the change in physical symptoms may induce false lower values.8The time interval chosen by us was 4–7 days in symptomatically similar patients which was optimum time interval for assessment of test-retest reliability as it eliminated bias due to memory effect as well as symptom fluctuation.The Brazilian Portuguese and Chinese versions of ODI achieved an ICC of 0.99 when retest was done within 24 hours.22,23 Other studies have reported values of ICC similar to present study (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Comparison with other studies.29

To ascertain the concurrent validity between VAS and ODI-P, spearman correlation was seen which was found to be 0.424 which is a moderately positive correlation. Other studies have also established a moderately positive correlation with pain and ODI scores. In one of the earliest studies on ODI, Gronblad M et al. showed that a positive co relation was seen between VAS and ODI(r = 0.62).24 Amongst the translated and cross culturally adapted versions our values were greater than the Turkish version(r=.367) and almost similar to the Korean(r = 0.425),Norwegian(r=.52),and Iranian(r = 0.54) versions.17,19,25,26 However the correlation was found to be greater in the Italian(r = 0.730) and the Brazilian (r = 0.66), and Marathi(r = 0.67) versions.2,22,27 As an instrument which might be considered as gold standard for assessment of disability due to LBP was lacking in Punjabi language, the convergent validity was not assessed. Some authors have circumvented the problem of absence of a comparative gold standard measure by using quality of life measures. For example, in the validation of Korean ODI, WHOQOL-BREF scale has been used. These quality of life scales have additional domains besides physical impairment and disability and as such their use as surrogate measures for measuring disability due to pain may lead to erroneous results.5

Factor analysis is an important determinant of the structural validity of the outcome measure. For factor analysis to be valid, a minimum sample size of 100 is required.11 Any item in the outcome instrument which does not load into a single factor or loads into multiple factors needs to be modified.5 ODI-P showed a single factor structure with a variance of 48.61%.A similar single factor structure was revealed in the Italian version with a total variance of 45%.27 However a two level structure was revealed in the German and the Arabic versions.18,28

There are a few limitations in the present study. We included patients of mechanical back ache only as pain is the primary physical determinant of disability in these patients, ideally this questionnaire should be tested in patients with low back pain of other origins also. The responsiveness of ODI-P was not measured. Additional studies need to be done to assess the responsiveness of ODI-P in a wide variety of clinical situations. Also, convergent validity using a similar patient reported outcome measure could not be assessed as a ‘gold standard’ tool was not available in Punjabi language but convergent validity with VAS was checked.

Conclusion: ODI-P is a valid and reliable instrument for the assessment of patients with back pain and is a single factor structure. It was well accepted by the patients and can be used in clinical as well as research settings for monitoring of progression of symptoms and objective assessment of pain and disability. This instrument can be used in actual comparison of outcomes with the international studies. It can also be used for evaluating validity of other back pain related questionnaires into Punjabi language in future.

Funding

None.

Declaration of competing interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Dinesh Sandal, Email: drdineshsandal@gmail.com.

Rohit Jindal, Email: rohitjindalortho@yahoo.com.

Sandeep Gupta, Email: drsandeepgupta1976@gmail.com.

Sudhir Kumar Garg, Email: sudhir_ortho@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Hoy D., Bain C., Williams G. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):2028–2037. doi: 10.1002/art.34347. Jun 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joshi V.D., Raiturker P, Kulkarni A.A. Validity and reliability of English and Marathi Oswestry disability index (version 2.1a) in. Indian Population: Spine. 2013;38(11):E662–E668. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31828a34c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa L.O.P., Maher C.G., Latimer J. Clinimetric testing of three self-report outcome measures for low back pain patients in Brazil: which one is the best? Spine. 2008;33(22):2459–2463. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181849dbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denis I., Fortin L. Development of a French-Canadian version of the Oswestry Disability Index: cross-cultural adaptation and validation. Spine. 2012;37(7):E439–E444. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318233eaf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costa L.O.P., Maher C.G., Latimer J. Self-report outcome measures for low back pain:searching for international cross-cultural adaptations. Spine. 2007;32(9):1028–1037. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000261024.27926.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaton Dorcas E. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000 Dec 5;25(24):3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fairbank J.C., Couper J., Davies J.B., O’Brien J.P. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66(8):271–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairbank J.C., Pynsent P.B. The Oswestry disability index. Spine. 2000;25(22):2940–2952. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairbank J.C. Why are there different versions of the Oswestry Disability Index? A review J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;(20):83–86. doi: 10.3171/2013.9.SPINE13344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roland M., Fairbank J. The roland-morris disability questionnaire and the Oswestry disability questionnaire. Spine. 2000;25(24):3115–3124. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao M., Wang Q., Li Z. A systematic review of cross-cultural adaptation of the Oswestry disability index. Spine. 2016;41(24):E1470–E1478. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishant Harvinder Singh Chhabra, Kapoor Kulwant Singh. New modified English and Hindi Oswestry disability index in low back pain patients treated conservatively in Indian population. Asian Spine. 2014;8(5):632–638. doi: 10.4184/asj.2014.8.5.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vincent J.I., Macdermaid J.C., Grewal R., Sekar V.P., Balchandran D. Translation of Oswestry disability index into Tamil with cross cultural adaptation and evaluation of reliability and validity. Open Orthop J. 2014;8:11–19. doi: 10.2174/1874325001408010011. Jan 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohan V.,G.S.P., Meravanigi G.,N.R., Yerramshetty J. Adaptation of the Oswestry disability index to Kannada language and evaluation of its validity and reliability. Spine. 2016;41(11):E674–E680. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu H, Tao H, Luo Z. Validation of the simplified Chinese version of the Oswestry disability index. Spine. 15;34(11):1211-1216. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Chow J.H., Chan C.C. Validation of the Chinese version of the Oswestry disability index. Work. 2005;25(4):307–314. Jan 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mousavi S.J., Parnianpour M., Mehdian H., Montazeri A., Mobini B. The Oswestry disability index, the roland-morris disability questionnaire, and the quebec back pain disability scale: translation and validation studies of the Iranian versions. Spine. 2006;31(14):E454–E459. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000222141.61424.f7. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osthus H., Cziske R., Jacobi E. Cross-cultural adaptation of a German version of the Oswestry disability index and evaluation of its measurement properties. Spine. 2006;31(14):E448–E453. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000222054.89431.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim D.Y., Lee S.H., Lee H.Y. Validation of the Korean version of the Oswestry disability index. Spine. 2005;30(5):E123–E127. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000157172.00635.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terwee C.B., Bot S.D.M., de Boer M.R. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pekkanen L., Kautiainen H., Ylinen J. Reliability and validity study of the Finnish version 2.0 of the Oswestry disability index. Spine. 2011;36(4):332–338. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181cdd702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vigatto R., Alexandre N.M.C., Filho H.R.C. Development of a Brazilian Portuguese version of the Oswestry disability index: cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity. Spine. 2007;32(4):481–486. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000255075.11496.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lue Y.-J., Hsieh C.-L., Huang M.-H. Development of a Chinese version of the Oswestry disability index version 2.1. Spine. 2008;33(21):2354–2360. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818018d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gronblad M., Hupli M., Wennerstrand P. Intercorrelation and test retest reliability of the Pain Disability Index (PDI) and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (ODQ) and their correlation with pain intensity in low back pain patients. Clin J Pain. 1993;9:189–195. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199309000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yakut E., Düger T., Oksüz C. Validation of the Turkish version of the Oswestry Disability Index for patients with low back pain. Spine. 2004;29(5):581–585. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000113869.13209.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grotle M., Brox J., Vollestad N. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Norwegian versions of the Roland-morris disability questionnaire and the Oswestry disability index. J Rehabil Med. 2003;35(5):241–247. doi: 10.1080/16501970306094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monticone M., Baiardi P., Ferrari S. Development of the Italian version of the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI-I): a cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity study. Spine. 2009;34(19):2090–2095. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181aa1e6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guermazi M., Mezghani M., Ghroubi S. The Oswestry index for low back pain translated into Arabic and validated in a Arab population. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2005;48(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.annrmp.2004.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miekisiak G., Kollataj M., Dobrogowski J., Kloc W., Linionka W., Banach M. Validation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Polish version of the Oswestry disability index. Spine. 2013;38(4):237–243. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31827e948b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]