Abstract

Background

Intra-operative fluoroscopy has been shown to improve the accuracy of acetabular component positioning when compared to no fluoroscopy in direct anterior approach (DAA) total hip arthroplasty (THA). Due to logistical reasons, our senior author has been performing DAA THA at one institution without the use of fluoroscopy and has created an intraoperative referencing technique to aid in acetabular component positioning. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the accuracy of acetabular component positioning using fluoroscopy when compared to an intra-operative referencing technique without fluoroscopy.

Methods

A total of 214 consecutive primary DAA THA were performed by one surgeon at two institutions and were retrospectively reviewed over a 3-year period. Intra-operative fluoroscopy was used with all patients at Institution A (N = 154). At institution B (N = 60), no fluoroscopy was used, and an intra-operative referencing technique was employed to assist in placement of the acetabular component.

Results

In the fluoroscopy group, 91% of components met our abduction target, 90% met our anteversion target, and 82.5% simultaneously met both targets. In the non-fluoroscopy group, 98% of components met our abduction target, 92% met our anteversion target, and 90% simultaneously met both targets. There was no difference between groups for placement of the component within both targets simultaneously (p = .171).

Conclusion

Use of our intra-operative referencing technique is non-inferior in placing acetabular components within a pre-defined safe zone when compared to use of intraoperative fluoroscopy. The intra-operative reference technique can be a helpful adjunct for ensuring accurate acetabular component positioning while simultaneously reducing cost and limiting radiation exposure.

Keywords: Total hip arthroplasty, Direct anterior approach, Fluoroscopy, Acetabular component positioning

1. Introduction

Improper orientation of the acetabular component in total hip arthroplasty (THA) has been linked as a risk factor for increased dislocation rates, bearing surface wear, limb-length discrepancy, pelvic osteolysis, and earlier time to revision.1 Given the importance of acetabular component orientation in THA outcomes, prior studies have strived to define the ideal acetabular component position and to identify techniques to reduce component malpositioning.

The orientation of an acetabular component is described by two key measurements. These measurements are obtained using a postoperative AP radiograph of the pelvis: the inclination angle, also known as the abduction angle, and the degree of acetabular cup anteversion. It is generally accepted that a ‘safe-zone’ exists for these two measurements, a term that describes the goal range of inclination angles and anteversion degrees whereby a THA acetabular component will have the lowest risk of complications.2,3 Most studies in the current literature define their target safe zones as an abduction angle of 30–45, 30–50 or 30–55, and target anteversion of 5–25, 5–35 or 5–40.4, 5, 6 This anteversion target was originally defined for the posterior approach, and there have been concerns regarding impingement when applying this same target with the anterior approach. Recent studies analyzing component positioning with the direct anterior approach, however, continue to strive for these classically described targets.7, 8, 9, 10 Operative techniques have been developed in hopes of increasing the reliability and consistency of achieving safe-zone component orientation.

Intraoperative fluoroscopy is commonly employed during direct anterior approach (DAA) THA due to the convenience of obtaining an AP pelvis film in the supine position. Some studies have demonstrated improved acetabular component positioning with the use of fluoroscopy compared to no fluoroscopy.3,4 However, intraoperative fluoroscopy may not always be available to surgeons based on limited resources or logistical constraints. Furthermore, the added cost, surgical time, and radiation exposure of fluoroscopy demands proof of superiority.11, 12, 13, 14

For these reasons, our senior author created an intraoperative referencing technique to aid in acetabular component positioning without the use of fluoroscopy. The intraoperative referencing technique was used by the senior author at one institution due to logistical reasons in lieu of fluoroscopy, while fluoroscopy continued to be used at a separate institution. The primary purpose of this study is to compare acetabular component positioning when using intraoperative fluoroscopy compared to an intraoperative referencing technique. Patient demographics and radiation exposure were also evaluated.

2. Methods

After receiving local Institutional Review Board approval, a retrospective chart review of all patients who underwent DAA THA by the senior author between 2015 and 2018 was performed. We identified 214 consecutive patients, mean age of 59.4 (range 28–73), who underwent primary DAA THA at two hospitals by one surgeon. The database was used to obtain information from each patient including laterality of the operatively treated hip, age, sex, height, weight, and BMI. The indication for THA as well as radiation exposure was also recorded. Intraoperative fluoroscopy was used with all patients at Institution A (N = 154). At Institution B (N = 60), no fluoroscopy was used, and an intra-operative referencing technique was employed to assist in placement of the acetabular component (Fig. 1). The surgeries performed at each institution were within the same time periods.

Fig. 1.

Schematic for intra-operative referencing technique. The long axis of the body is defined by a line connecting the xyphoid process and the umbilicus. The transverse axis is defined as a line between the two ASIS and should be 90° from the long axis.

For the intraoperative referencing technique, the patient is positioned supine on a regular radiolucent operating room table (Jackson table) and draped with the umbilicus exposed. The referencing technique involves the use of a four-point measurement technique using 2 axes. The long axis of the body is defined as a line connecting the xiphoid process and the umbilicus, while the transverse axis is defined as a line between the two ASIS and should be 90 ° from the long axis. The xiphoid process is palpated over the drapes and a line is drawn on the drapes connecting the xiphoid process to the umbilicus. The horizontal line between the two ASIS points is then drawn. A bovie cord is a useful straight edge when drawing the lines. The impaction handle alignment is then implemented at a 45 ° angle from the intersection of the transverse and long axis body line intersections.

For the statistical analysis, we defined target ranges for abduction (30–55 °) and anteversion (5–35 °). These target ranges are the predetermined goal of the senior author and have been previously described in the literature.1 Acetabular component abduction and anteversion angles were calculated using PACS software based on the first postoperative clinic radiograph by two orthopedic surgery residents. The abduction angle was calculated off of a horizontal line created by drawing a tangential line through the bilateral tear drops, ischium, or ischial spines. The anteversion was calculated by first drawing an ellipse around the acetabular cup and then taking the inverse sine of the (short axis/long axis) of the ellipse as described by Bacchal et al.1 The intraclass correlation coefficient for measurement validity of the abduction and anteversion angles was 0.917 and 0.939, respectively. Measurement values obtained by each interpreter were averaged to create a composite value. Component positioning, patient related factors, and radiation exposure were compared between groups.

An a priori power analysis was performed to determine the minimum number of patients to include to identify a difference in the combined safe zone component rates. With an alpha of 0.05 and a power of 0.80, the projected sample size needed in the fluoroscopy group (Institution A) was 87 and in the non-fluoroscopy group (Institution B) was 44. Statistical significance was defined as p < .05. Categorical data were analyzed with the chi-square test and continuous data were analyzed with the independent-samples t-test and ANOVA Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM Corporation’s SPSS Version 26.0 software.

3. Results

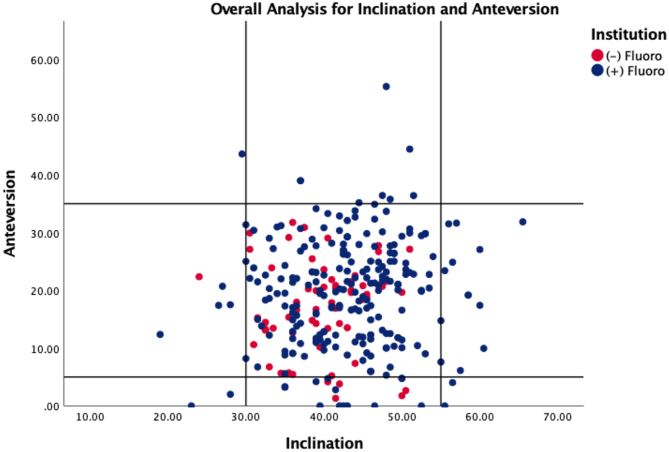

The fluoroscopy group was significantly older with a higher proportion of patients undergoing surgery for primary osteoarthritis (p < .001) (Table 1). In the fluoroscopy group, the mean abduction angle was 43 ° (43.85 ± 7.3) and the mean anteversion angle was 21 ° (20.42 ± 9.3), while the non-fluoroscopy group mean abduction angle was 40 ° (39.7 ± 5.7) and the mean anteversion angle was 17 ° (17.1 ± 7.9). In the fluoroscopy group, 91% of components met our abduction target, 90% met our anteversion target, and 82.5% simultaneously met both targets. In the non-fluoroscopy group, 98% of components met our abduction target, 92% met our anteversion target, and 90% simultaneously met both targets. There was no statistical difference in the rate of component placement within the pre-defined safe zones between the groups. 1.6% of components in the fluoroscopy group were considered outliers, placed out of both the abduction and anteversion safe zone, whereas there were no outliers in the non-fluoroscopy group (p = .561) (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Patient demographics, surgical indication, and radiation exposure with bivariate analysis comparing fluoroscopy to non-fluoroscopy groupsa.

| Fluoroscopy |

Non-Fluoroscopy |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 154) | (N = 60) | p-value | |

| Age (years, Mean ± SD) | 59.4 ± 11.3 | 52.7 ± 10.3 | <.001 |

| Laterality | 0.855 | ||

| Left | 48.10% | 46.70% | |

| Right | 51.90% | 53.30% | |

| BMI (Mean, SD) | 28.29 ± 4.4 | 27.4 ± 5.5 | 0.26 |

| Obesity group | 0.27 | ||

| non-obese, BMI<30 | 64.90% | 67.30% | |

| obese, 30 < BMI<40 | 35.10% | 30.60% | |

| Morbidly obese, BMI>40 | 0.00% | 2.00% | |

| Indication | <.001 | ||

| AVN | 27.50% | 61.70% | |

| Primary OA | 59.50% | 26.70% | |

| Dysplasia | 11.10% | 10.00% | |

| Post-Traumatic | 1.30% | 1.70% | |

| Inflammatory | 0.70% | 0.00% | |

| Radiation Exposure (mGy) (Avg, SD) | 1.03 (.96)% | NA |

SD = Standard Deviation, BMI = Body Mass Index, AVN = Avascular Necrosis, OA=Osteoarthritis.

Boldface indicates statistical significance.

Table 2.

Acetabular Component Positioning within defined target range with bivariate analysis comparing fluoroscopy and non-fluoroscopy groupsa.

| Fluoroscopy |

Non-Fluoroscopy |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 154) | (N = 60) | p-value | |

| Abduction (mean, SD) | 43.85 ± 7.3 | 39.7 ± 5.7 | <.001 |

| Abduction in Safe Zone? | 0.073 | ||

| No | 9.10% | 1.70% | |

| Yes | 90.90% | 98.30% | |

| Anteversion (mean, SD) | 20.42 ± 9.3 | 17.1 ± 7.9 | 0.015 |

| Anteversion in Safe Zone? | 0.65 | ||

| No | 10.40% | 8.30% | |

| Yes | 89.60% | 91.70% | |

| Combined Safe Zone? | 0.171 | ||

| No | 17.50% | 10.00% | |

| Yes | 82.50% | 90.00% | |

| Outliers? | 0.561 | ||

| no | 98.10% | 100.00% | |

| yes | 1.90% | 0.00% |

SD = Standard Deviation.

Boldface indicates statistical significance.

Fig. 2.

Scatterplot for acetabular component measurements comparing the fluoroscopy to no-fluoroscopy groups.

To determine if any pre-operative variables were associated with accurate combined safe zone placement, patient demographic variables and indications for surgery were compared between groups with accurate and inaccurate component placement. The only patient related factor associated with component positioning was a pre-operative diagnosis of post-traumatic arthritis (p < .001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Evaluation of patient pre-operative factors and acetabular component position within combined safe zones.

| Within Combined Safe Zone |

Not Within Combined Safe Zone |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 181) | (N = 33) | p-value | |

| Age (years, Mean ± SD) | 58.3 ± 10.1 | 57.3 ± 12.3 | 0.716 |

| Laterality | 0.918 | ||

| Left | 84.30% | 15.70% | |

| Right | 84.80% | 15.20% | |

| BMI (Mean, SD) | 27.6 ± 4.8 | 28.4 ± 4.6 | 0.26 |

| Obesity group | 0.08 | ||

| non-obese, BMI<30 | 84.50% | 15.50% | |

| obese, 30 < BMI<40 | 89.60% | 10.40% | |

| Morbidly obese, BMI>40 (N = 1) | 0.00% | 100.00% | |

| Indication | <.001 | ||

| AVN | 87.30% | 12.70% | |

| Primary OA | 82.20% | 17.80% | |

| Dysplasia | 87.00% | 13.00% | |

| Post-Traumatic | 66.70% | 33.30% | |

| Inflammatory (N = 1) | 100.00% | 0.00% |

SD = Standard Deviation, BMI = Body Mass Index, AVN = Avascular Necrosis, OA=Osteoarthritis.

∗Boldface indicates statistical significance.

The average radiation exposure was 1.03 mGy per patient in the fluoroscopy group, whereas there was no intra-operative radiation exposure in the non-fluoroscopy group (Table 1).

4. Discussion

The proper positioning of the acetabular component in THA is critical in order to minimize complications including dislocation rates, limb-length discrepancy, component impingement, bearing surface wear, pelvic osteolysis and revisions in the long term.2 Due to logistical constraints, we have the unique ability to compare the outcomes of patients treated with acetabular component positioning using an intraoperative referencing technique without fluoroscopy versus patients treated with fluoroscopy. We designed this study in order to evaluate the accuracy of acetabular component positioning, patient related factors, and radiation exposure using fluoroscopy when compared to an intraoperative referencing technique without fluoroscopy.

Our results demonstrate that intraoperative referencing is non-inferior to intraoperative fluoroscopy in achieving acceptable acetabular cup positioning. These results are similar to findings observed in a recent study by Holst et al.8 The current investigation not only supports the conclusion that intraoperative referencing is non-inferior, but it also provides instruction for executing our specific technique. Other studies have argued that the sole use of anatomic landmarks leads to acetabular component malpositioning due to variations in pelvic orientation.3 However, at least 90% of patients in both arms of the current study had acetabular components positioned within the target abduction and anteversion safe zone. Furthermore, this study confirms that an intraoperative referencing technique allows for reproducible placement of acetabular components within a targeted zone. Beyond achieving acceptable component positioning, intraoperative referencing may offer advantages over fluoroscopy. The advantages include decreased cost and resource utilization, improved efficiency and decreased radiation exposure to the patient, surgeon and staff.

Intraoperative referencing using anatomic landmarks is not only efficient, but it is also free. Any additional resources used during surgery increase costs to hospitals, surgeons and ultimately, patients. Fluoroscopy increases surgical costs in multiple ways, including longer operative time and requiring the use of an x-ray technician. The equivalent acetabular positioning between the two techniques seen in our study, and in concordance with results of prior studies, defends the decision of some surgeons to forego fluoroscopy in DAA THA to avoid this increased cost.15, 16, 17

Apart from cost, the referencing technique eliminates the associated radiation exposure of fluoroscopy. It has been demonstrated that radiation exposure to patients during fracture surgery of the acetabulum and femur is associated with a small, yet higher cancer incidence.18 On the other hand, one study found that fluoroscopic radiation to the patient during DAA THA is roughly equivalent to that of a screening mammogram, suggesting intraoperative fluoroscopy poses negligible risk.15, 16, 17 Regarding risk to the surgeon, we know that orthopedic surgeons have a higher lifetime risk of radiation exposure and associated cancer risk.11,16,17 One study found that over 300,000 direct anterior THA surgeries would need to be performed with fluoroscopy before reaching a radiation threshold dose that could result in cataracts.16,17 In summary, there is a minimal, but non-zero risk associated with radiation exposure to the patient, surgeon and staff when using intraoperative fluoroscopy for DAA THA.

Barrack et al. have previously published on the increased risk of missing the target zone for acetabular component placement in THA with increasing BMI.2 Although their results demonstrated that the odds for malpositioning increased by ≥ 0.2 for each 5 kg/m2, we did not find any statistically significant associations between a patient’s BMI and the incidence of acetabular component malpositioning for either inclination or anteversion when performing DAA THA. Our findings are aligned with the findings of Gosthe et al.5

Potential weaknesses of this study include that lack of comparison of surgical time. Without this data, we cannot definitively conclude that intraoperative referencing decreases surgical time or is more efficient than intraoperative fluoroscopy. In addition, our data did not address the possible advantages or disadvantages of fluoroscopy as they relate to leg length discrepancy, off-set and medialization of the cup. Medialization was not evaluated due to the difficulty in retrospectively quantifying desired cup positioning without preoperative templates for the non-fluoroscopy cases. Leg length discrepancy was not evaluated as a comparable outcome due to the wide variability of preoperative leg length discrepancies.

In conclusion, intraoperative referencing is non-inferior to fluoroscopy for achieving appropriate acetabular component positioning. The intraoperative reference technique can be used as a helpful adjunct for ensuring accurate acetabular component positioning, while simultaneously reducing cost, improving accessibility, and limiting radiation exposure to the surgeon and staff. Further study is needed to evaluate differences in surgical time, leg length discrepancy and cup medialization.

References

- 1.Bachhal V. A new method of measuring acetabular cup anteversion on simulated radiographs. Int Orthop. 2012;36(9):1813–1818. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1583-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrack R.L. Accuracy of acetabular component position in hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(19):1760–1768. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slotkin E.M., Patel P.D., Suarez J.C. Accuracy of fluoroscopic guided acetabular component positioning during direct anterior total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9):102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jennings J.D. Intraoperative fluoroscopy improves component position during anterior hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2015;38(11):e970–e975. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20151020-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gosthe R.G. Fluoroscopically guided acetabular component positioning: does it reduce the risk of malpositioning in obese patients? J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(10):3052–3055. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman G.P. Intraoperative fluoroscopy with a direct anterior approach reduces variation in acetabular cup abduction angle. Hip Int. 2017;27(6):573–577. doi: 10.5301/hipint.5000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soderquist M.C., Scully R., Unger A.S. Acetabular placement accuracy with the direct anterior approach freehand technique. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9):2748–2754. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holst D.C. Does the use of intraoperative fluoroscopy improve postoperative radiographic component positioning and implant size in total hip arthroplasty utilizing a direct anterior approach? Arthroplast Today. 2020;6(1):94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2019.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercer N. Optimum anatomic socket position and sizing for the direct anterior approach: impingement and instability. Arthroplast Today. 2019;5(2):154–158. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergin P.F., Unger A.S. Direct anterior total hip arthroplasty. JBJS Essent Surg Tech. 2011;1(3):e15. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.ST.K.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mastrangelo G. Increased cancer risk among surgeons in an orthopaedic hospital. Occup Med (Lond) 2005;55(6):498–500. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqi048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giordano B.D. Radiation exposure issues in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(12) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01328. e69(1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tannast M. Accuracy and potential pitfalls of fluoroscopy-guided acetabular cup placement. Comput Aided Surg. 2005;10(5-6):329–336. doi: 10.3109/10929080500379481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tischler E.H. Does intraoperative fluoroscopy improve component positioning in total hip arthroplasty? Orthopedics. 2015;38(1):e1–6. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20150105-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curtin B.M. Patient radiation exposure during fluoro-assisted direct anterior approach total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(6):1218–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayda R.A. Radiation exposure and health risks for orthopaedic surgeons. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018;26(8):268–277. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pomeroy C.L. Radiation exposure during fluoro-assisted direct anterior total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(8):1742–1745. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beebe M.J. Prospective assessment of the oncogenic risk to patients from fluoroscopy during trauma surgery. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30(7):e223–e229. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]