Abstract

Aim

Lung metastases are a negative prognostic factor in Ewing sarcoma, however, the incidence and significance of sub-centimetre pulmonary nodules at diagnosis is unclear. The aims of this study were to (1): determine the incidence of indeterminate pulmonary nodules (IPNs) in patients diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma (2); establish the impact of IPNs on overall and metastasis-free survival and (3) identify patient, oncological and radiological factors that correlate with poorer prognosis in patients that present with IPNs on their staging chest CT.

Materials & methods

Between 2008 and 2016, 173 patients with a first presentation of Ewing sarcoma of bone were retrospectively identified from an institutional database. Staging and follow-up chest CTs for all patients with IPN were reviewed by a senior radiologist. Clinical and radiologic course were examined to determine overall- and metastasis-free survival for IPN patients and to identify demographic, oncological or nodule-specific features that predict which IPN represent true lung metastases.

Results

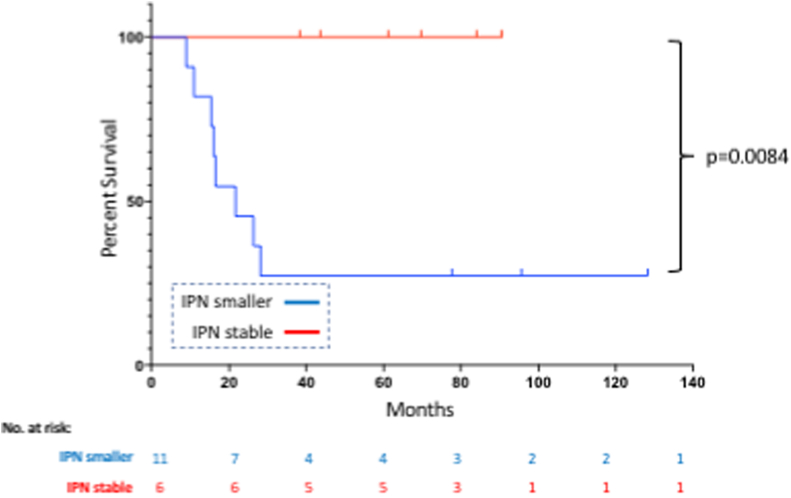

Following radiologic re-review, IPN were found in 8.7% of patients. Overall survival for IPN patients was comparable to those with a normal staging chest CT (2-year overall survival of 73.3% [95% CI 43.6–89] and 89.4% [95% CI 81.6–94], respectively; p = 0.34) and was significantly better than for patients with clear metastases (46.0% [95% CI 31.9–59]; p < 0.0001). Similarly, there was no difference in metastasis-free survival between ‘No Metastases’ and ‘IPN’ patients (p = 0.16). Lung metastases developed in 40% of IPN patients at a median 9.6 months. Reduction of nodule size on neoadjuvant chemotherapy was associated with worse overall survival in IPN patients (p = 0.0084).

Conclusion

IPN are not uncommon in patients diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma. In this study, we were unable to detect a difference in overall- or metastasis-free survival between patients with IPN at diagnosis and patients with normal staging chest CTs.

Keywords: Ewing sarcoma, Lung nodules, Survival

1. Introduction

Lung metastases are a negative prognostic factor in primary bone sarcomas. For Ewing sarcoma, the five-year overall survival rate for patients with localized disease at the time of diagnosis is 65–75%.1, 2, 3 Those with lung metastases have an expected overall survival of 25–35% at this same timepoint.2, 3, 4 While approximately 25% of Ewing sarcoma patients present with clear lung metastases,5,6 typically defined as a parenchymal nodule greater than 10 mm in diameter,7 many others have smaller lung lesions (indeterminate pulmonary nodules or IPN), on their staging chest CT scans. We recently demonstrated that 16% of patients with high-grade osteosarcoma and spindle cell sarcoma of bone have IPN on diagnosis and that their overall survival is worse than those with negative staging chest CTs.8 The rate and prognostic significant of IPN in Ewing sarcoma is unknown but has important treatment implications. Ewing sarcoma is typically treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, en-bloc surgical excision of the tumour followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. Unlike other primary bone sarcomas, Ewing sarcoma is radiosensitive and therefore radiation can be used either in addition to or instead of surgery. While definitive radiotherapy is less effective than surgery at achieving local control,3,9,10 it is a viable option, particularly if the patient’s prognosis is guarded or the resection is excessively morbid. For instance, a patient with a pelvic tumour and lung metastases would be offered definitive radiotherapy to treat their disease instead of a hemipelvectomy, an operation associated with a high complication rate, long post-operative recovery and significant functional impairment. It is unclear which approach should be taken for a patient with a similar tumour but sub-centimetre lung nodules (i.e. IPN) on their staging chest CT.

IPNs pose a particular clinical dilemma as they are a common incidental finding11,12 but their small size precludes biopsy and as definitive treatment is carried out within a few months of diagnosis, monitoring for progression over time is not possible. Instead, the presence or absence of lung disease is determined radiologically even though there are no established features to differentiate benign from malignant pulmonary nodules in sarcoma11, 13, 14, 15.

The objectives of this study were therefore to (1): determine the incidence of IPNs in patients diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma (2); establish the impact of IPNs on metastasis-free and overall survival and (3) identify patient, oncological and radiological factors that correlate with poorer prognosis in patients that present with IPNs on their staging chest CT.

2. Methods

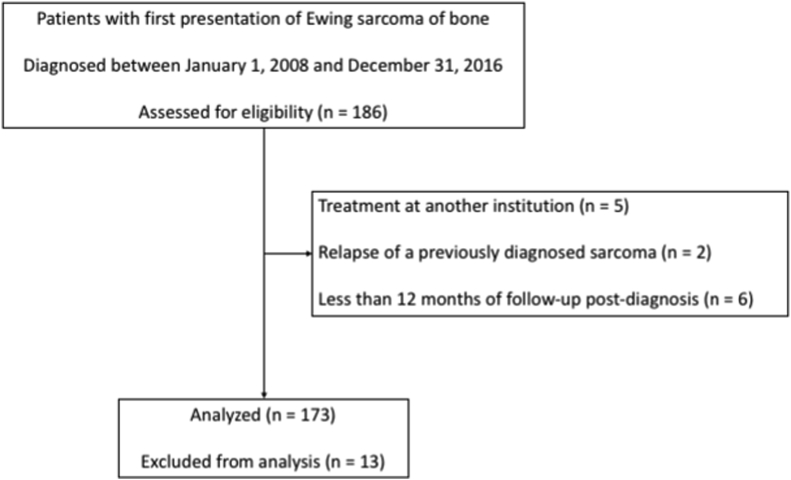

Following ethics board approval, patients diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma between January 1st, 2008 and December 31st, 2016 were identified using a prospectively-collected institutional database. Patients previously treated at another institution (n = 5), presenting with relapse of a previously diagnosed sarcoma (n = 2) and those with less than 12 months of follow-up (n = 6) were excluded from the analysis (see Fig. 1). Patient and treatment details as well as clinical outcomes were retrieved from the database and clinical notes. All patients were reviewed at both the institutional sarcoma multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting as well as the United Kingdom’s National Ewing’s MDT and treatment decisions, including chemotherapy regimen, local control strategy and whether patients received whole lung radiation and/or thoracotomy, were made based on a consensus from these two groups as per the standard of care at the time.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart that shows the cohort included in this study.

Variables included age, gender, location (axial vs appendicular), size (maximum diameter on presentation MRI) and presence of extra-pulmonary or skip metastases. Treatment factors that were considered included percentage necrosis of the resection specimen and local control strategy for the primary site. Patients were divided into three groups: limb salvage, amputation and chemotherapy/radiation only. Clinical course was evaluated to calculate metastasis-free and overall survival. Date of lung metastasis was defined as the earliest occurrence of: increase in the maximal diameter of a lung nodule on follow-up chest CT, appearance of a new lung nodule on follow-up chest CT, date of thoracotomy with confirmatory pathology or clear documentation by the treating oncologist of the presence of lung metastases on a locally performed chest CT.

Patients were first classified into one of three categories based on the initial radiology report: ‘no metastases’, ‘metastases’ and ‘IPN’. Following Rissing et al.,7 patients with a parenchymal nodule of 10 mm or greater were placed in the ‘metastasis’ group. An IPN was defined as a parenchymal nodule with a maximum diameter of 9 mm or less. All patients with abnormal findings on their staging chest CT underwent radiologic re-review by a senior consultant radiologist to identify those with nodules consistent with a benign diagnosis. Chest imaging was evaluated based on guidelines published by the British Thoracic Society16 and for lung cancer screening.17 This approach was utilized during our previous study on osteosarcoma.18 First, thin (1 mm) and thick (5 mm) slices in the lung window were screened to identify suspicious nodules. Second, if the nodule was absent on the maximum intensity projection (MIP), it was removed from consideration. If the nodule was present on the MIP, a correlation was performed in multiplanar formats. Third, the window was changed to soft tissue. If the nodule was absent, it was judged to be a vessel. If the nodule was present but within a fissure, it was judged to be a lymph node. If on soft tissue windows, the nodule had the appearance of thickened septa, it was judged to be a pleural tag. All other nodules were categorized as IPN. Using this approach, five patients were found to have benign pulmonary lesions. Of these, four were moved to the ‘no metastasis’ category while the other patient also had a bone metastasis and was moved to the ‘metastasis’ group. Second, the staging chest CT for ‘IPN’ patients was examined for the following variables: number of IPNs, distribution of IPNs (one or both lungs) and characteristics of the largest IPN (diameter, intra-pulmonary location, distance from pleura (<1 cm = peripheral; >1 cm = central), presence of mineralization and shape (1 = round with clear margins, 2 = round with ill-defined margins or 3 = lobular). All subsequent chest CTs were examined to re-evaluate nodules identified on the staging CT and to identify any new nodules. Specifically, it was noted whether nodules had changed in size or mineralized compared to the previous scan. Nodule change was considered significant if the diameter increased or decreased by a minimum of 25%.16

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 8 (Graphpad Software) and SPSS (Version 26, IBM Corporation). The primary outcome measure was overall survival, which was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method (Mantel-Cox test) as the time between the date of diagnosis and the date of death from any cause. The secondary outcome measure was disease-free survival, which was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method (Mantel-Cox test) as the time between the date of diagnosis and the date of metastasis (see above criteria). Outcomes for living patients were censored at the time of their last follow-up. Multivariate analysis was conducted using Cox Regression and equivalence between groups was evaluated using Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA, Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

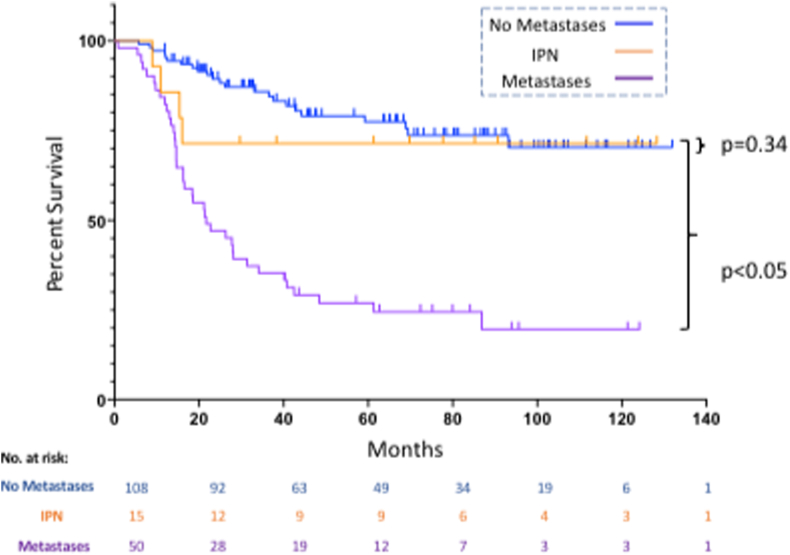

We identified 173 patients with Ewing Sarcoma that met the inclusion criteria. Overall survival at two- and five-years post-diagnosis was 74.7% [95% CI 67.4–80.6] and 60.6% [95% CI 52.3–67.9], respectively. Median follow-up was 68.4 months (range 12.0–131.9 months). Patient and oncological details are shown in Table 1. Multivariate analysis demonstrated better overall survival for patients that had greater than 90% chemotherapy-induced necrosis, were treated surgically and had no metastases on diagnosis. Following radiologic re-review of all patients with abnormal findings on their staging chest CT and using 10 mm as the cut-off to differentiate an indeterminate nodule (IPN) from a lung metastasis, 13.8% (n = 24) of patients had IPNs (pulmonary nodule <10 mm) on their staging chest CT. An additional 23.7% of patients had lung metastases (pulmonary nodule ≥10 mm) on presentation. Of the 24 patients with IPN, 9 had additional sites of disease including lymph node metastases (n = 2), skip metastases (n = 2) and distant bone metastases (n = 5). In order to investigate the impact of IPN on overall survival, only patients with isolated IPN on presentation were considered (n = 15). The remainder (n = 9) were pooled with patients with clear metastases on presentation. Though the number of IPN patients was small, their overall survival was not significantly different than for patients with normal staging chest CTs (two-year overall survival of 73.3% [95% CI 43.6–89] and 89.4% [95% CI 81.6–94], respectively; p = 0.34; see Fig. 2, Table 1). Both groups had significantly better prognoses than patients with skip or distant metastases whose two-year overall survival was 46.0% [95% CI 31.9–59] (p < 0.05 vs both groups). Demographic and oncologic variables were compared between the three groups. While there were no differences in age, gender or tumour size, local control strategy, tumour site and chemotherapy-induced necrosis differed. For all variables, the ‘No Metastases’ and ‘IPN’ groups were comparable while the ‘Metastases’ group had a higher percentage of patients that were treated non-operatively, had axial tumours and experienced less than 90% chemotherapy-induced necrosis (see Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Impact of demographic and oncologic variables on overall survival. Two-year overall survival (OS) was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. All variables significant in univariate analysis (p < 0.05) were entered into multivariate analysis (HR = hazard ratio; IPN = indeterminate pulmonary nodule).

| No. | % | 2 year OS | Univariate p value | Multivariate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | p value | ||||||

| Age | <40 years | 164 | 94.8 | 75.0% | 0.261 | ||

| ≥40 years | 9 | 5.2 | 77.8% | ||||

| Gender | Male | 97 | 56.1 | 72.9% | 0.334 | ||

| Female | 76 | 43.9 | 77.9% | ||||

| Local Control | Limb Salvage | 105 | 60.7 | 94.1% | <0.0001 | Ref | |

| Amputation | 17 | 9.8 | 70.6% | 1.809 | 0.215 | ||

| Chemo/Rads Only | 51 | 29.5 | 37.2% | 2.801 | 0.048 | ||

| Tumour Size | 0–7.9 cm | 43 | 24.9 | 83.1% | 0.142 | ||

| ≥8.0 cm | 129 | 74.6 | 73.2% | ||||

| Pathological Fracture | No | 152 | 87.9 | 74.5% | 0.788 | ||

| Yes | 21 | 12.1 | 79.6% | ||||

| Tumour Site | Extremity | 94 | 54.3 | 82.7% | 0.001 | Ref | |

| Axial | 78 | 45.1 | 65.5% | 1.37 | 0.273 | ||

|

Chemotherapy-Induced Necrosis |

<90% | 41 | 23.7 | 68.0% | <0.0001 | Ref | |

| ≥90% | 80 | 46.2 | 98.6% | 0.226 | 0.001 | ||

| Stage | No Metastases | 108 | 62.4 | 89.4% | <0.0001 | Ref | |

| IPN | 15 | 8.7 | 73.3% | 1.853 | 0.227 | ||

| Metastases | 50 | 28.9 | 46.0% | 2.151 | 0.014 | ||

Fig. 2.

This figure shows overall survival for patients with no metastases, IPN, or metastases at diagnosis. At 2 years, patients with IPNs had an overall survival of 73.3% while those with no metastases at diagnosis had an overall survival rate of 89.4% (p = 0.34). The worst outcomes were experienced by patients with metastases, whose 2-year overall survival was 46.0% (p < 0.001).

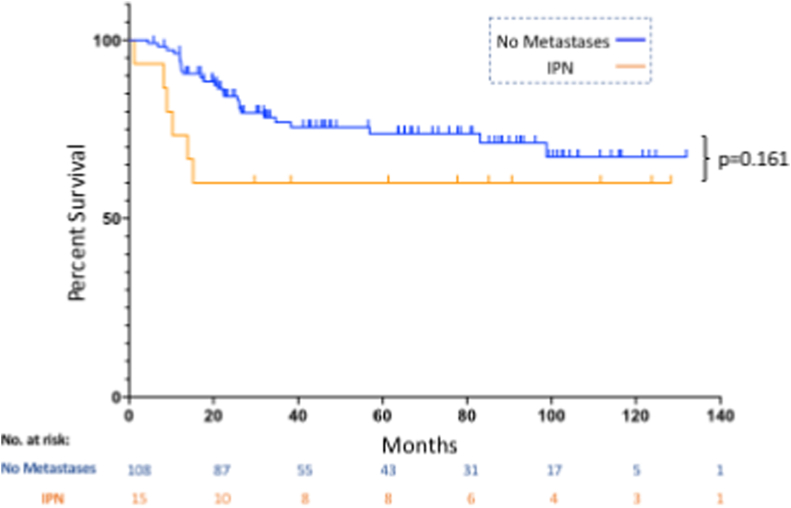

Metastasis-free survival was found to be dependent on gender and chemotherapy-induced necrosis on multivariate analysis with improved outcomes in female patients and those with greater than 90% response (see Table 2). We were unable to detect a significant difference in metastasis-free survival between patients that had IPN on their staging chest CT and patients with normal chest CTs at diagnosis (p = 0.161, see Fig. 3). Of the 15 patients with IPN on their staging chest CT, six (40%) developed clear metastases in a median of 9.6 months (range 1.2–15.2) post-diagnosis.

Table 2.

Impact of demographic and oncologic variables on metastasis-free survival. Two-year metastasis-free survival (MFS) was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. All variables significant in univariate analysis (p < 0.05) were entered into multivariate analysis (HR = hazard ratio; IPN = indeterminate pulmonary nodule).

| No. | % | 2 year MFS | Univariate p value | Multivariate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | p value | ||||||

| Age | <40 years | 116 | 94.3 | 83.0% | 0.004 | Ref | |

| ≥40 years | 7 | 5.7 | 47.6% | 3.086 | 0.348 | ||

| Gender | Male | 65 | 52.8 | 73.1% | 0.023 | Ref | |

| Female | 58 | 47.2 | 90.6% | 0.348 | 0.011 | ||

| Local Control | Limb Salvage | 92 | 74.8 | 87.7% | <0.0001 | Ref | |

| Amputation | 13 | 10.6 | 84.6% | 0.578 | 0.474 | ||

| Chemo/Rads Only | 18 | 14.6 | 37.4% | 5.53 | 0.091 | ||

| Tumour Size | 0–7.9 cm | 36 | 29.3 | 85.4% | 0.575 | ||

| ≥8.0 cm | 86 | 69.9 | 80.6% | ||||

| Pathological Fracture | No | 107 | 87.0 | 80.4% | 0.524 | ||

| Yes | 16 | 13.0 | 87.5% | ||||

| Tumour Site | Extremity | 69 | 56.1 | 89.7% | 0.002 | Ref | |

| Axial | 54 | 43.9 | 69.9% | 2.023 | 0.121 | ||

| Chemotherapy-Induced Necrosis | <90% | 27 | 22.0 | 73.7% | <0.0001 | Ref | |

| ≥90% | 74 | 60.2 | 91.8% | 0.204 | 0.001 | ||

| Stage | No Metastases | 108 | 87.8 | 84.3% | 0.161 | ||

| IPN | 15 | 12.2 | 60.0% | ||||

Fig. 3.

This figure shows metastasis-free survival for patients with no metastases or IPNs at diagnosis. At 2 years, patients with IPNs had a metastasis-free survival of 60% while those with normal staging chest CTs had a metastasis-free survival of 84.3% (p = 0.16).

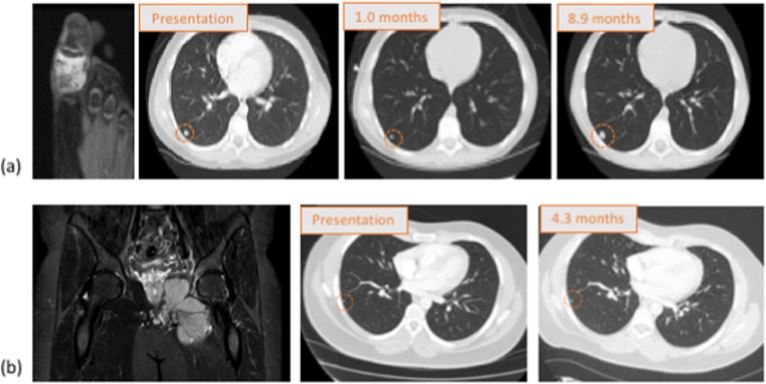

The next aim of this study was to identify demographic, oncological and radiological factors that correlated with poorer prognosis in IPN patients. As the number of IPN patients that developed metastases was low, the raw data for both IPN patients that did and did not develop systemic disease is shown in Table 3a, Table 3ba and 3b, respectively. A number of trends are observed. First, 85.7% (6 out of 7) patients that had four or more IPNs on their staging chest CT went on to develop metastatic disease. In all patients, the nodules occurred in both lungs. Second, 83.3% (5 out of 6) IPN patients that developed metastases eventually died of their disease. Third, only two of the six patients that developed metastases had disease isolated to the lung. Two patients developed bone metastases, another had lymph node metastases and a third developed simultaneous lung and liver metastases. Finally, there appeared to be a correlation between IPN response to chemotherapy and survival. In order to explore this further, all 24 IPN patients were examined (including those with other sites of disease at presentation). Staging and pre-operative chest CTs were available for 17 patients. Re-staging scans were performed at a median of 3.0 months post-initial CT and followed administration of induction chemotherapy. Pulmonary nodules diminished in size or vanished in 11 patients and remained stable in 6 patients (see Fig. 4 for examples). Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that IPN patients whose lung disease responded to neoadjuvant chemotherapy at this timepoint had significantly worse overall survival than patients with nodules that remained stable (p = 0.0084; see Fig. 5). No nodules mineralized following neo-adjuvant chemotherapy.

Table 3a.

Patients with isolated IPN on presentation that did not develop metastases.

| ID | Tumour Location | Tumour Size (cm) | Local Control | Necrosis | IPN Characteristics |

Survival (months) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter (mm) | No. | Mineralized | Distribution | Shape | Response to Chemo | ||||||

| 8F | Humerus | 16.0 | LSS | 80% | 3 | 1 | no | – | 1 | No CT | Alive free of disease (111.7) |

| 14 M | Tibia | 5.0 | LSS | 100% | 2 | 2 | yes | Unilateral | 1 | Smaller | Alive free of disease (77.7) |

| 8 M | Pelvis | 11.0 | LSS | 100% | 8 | 3 | no | Bilateral | 1 | Smaller | Alive free of disease (128.3) |

| 5F | Femur | 11.7 | LSS | 100% | 3 | 4 | no | Bilateral | 1 | No CT | Alive free of disease (123.8) |

| 13 M | Pelvis | 9.1 | LSS | n/a∗ | 3 | 2 | no | Unilateral | 2 | Stable | Alive free of disease (90.6) |

| 5F | Humerus | 13.2 | LSS | n/a∗ | 4 | 1 | no | – | 2 | No CT | Alive free of disease (85.2) |

| 33 M | Pelvis | 11.9 | LSS | 50% | 2 | 1 | yes | – | 2 | Stable | Alive free of disease (38.3) |

| 9F | Tibia | 12.5 | Amp | 90% | 4 | 1 | no | – | 2 | Stable | Alive free of disease (61.3) |

| 54 M | Metacarpal | 1.7 | Amp | n/a | 5 | 3 | no | Bilateral | 1 | n/a | Alive free of disease (29.7) |

Table 3b.

Patients with isolated IPN on presentation that did develop metastases.

| ID | Tumour Location | Tumour Size (cm) | Local Control | Necrosis | IPN Characteristics |

Time to Mets (mos) | Location Mets | Survival (months) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter (mm) | No. | Mineralized | Distribution | Shape | Response to Chemo | ||||||||

| 11 M | Toe | 2.1 | Amp | 25% | 8 | >5 | no | Bilateral | 1 + 2 | Smaller | 8.9 | Lung | Dead of disease (16.0) |

| 55 M | Pelvis | 15.0 | Radiation | n/a | 7 | 5 | no | Bilateral | 3 | Smaller | 8.2 | Lung + Liver | Dead of disease (8.9) |

| 8 M | Femur | 8.0 | LSS | 100% | 3 | 5 | no | Bilateral | 2 | Stable | 15.2 | Lung | Alive free of disease (69.8) |

| 31 M | Ribs | 8.3 | LSS | 75% | 6 | 4 | no | Bilateral | 2 | Smaller | 10.3 | LR then Bone | Dead of disease (15.4) |

| 17 M | Pelvis | 12.0 | Radiation | n/a | 3 | 5 | no | Bilateral | 1 | Smaller | 1.2 | Bone | Dead of disease (10.9) |

| 32 M | Tibia | 9.0 | LSS | 99% | 4 | 5 | no | Bilateral | 2 | Smaller | 13.8 | LN | Dead of disease (26.3) |

Fig. 4.

(a) This figure shows an example of reduction in size of an IPN on neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Shown is a representative slice from a T2-weighted MRI of an 11-year-old male with Ewing sarcoma of the proximal phalanx of his great toe. Staging chest CT revealed greater than 5 IPN, the largest measuring 8 mm in diameter. The IPN decreased in size while on neoadjuvant chemotherapy and then progressed at 8.9 months post-diagnosis. The patient died of disease 16.0 months after diagnosis.

(b) This figure shows an example of IPN stability. Shown is a representative slice from a T2-weight MRI of a 33-year-old male with Ewing sarcoma of the left hemipelvis. He had a single 2 mm IPN on staging chest CT that did not change in size on neoadjuvant chemotherapy. He did not develop metastases and was alive, free of disease 61.3 months post-diagnosis.

Fig. 5.

This figure shows overall survival for IPN patients whose nodules reduced in size (IPN smaller) or remained the same size (IPN stable) following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. No patients had IPN that increased in size during this period.

4. Discussion

Lung metastases on presentation are a poor prognostic factor in Ewing sarcoma.2, 3, 4, 5 However, the impact of sub-centimetre parenchymal lesions (indeterminate pulmonary nodules or IPN) on patient survival is unknown. An accurate estimation of life-expectancy is important when planning how to manage the primary tumour because several treatment options are available in this disease. Surgical resection carries significant morbidity both in the short and long-term as tumours are often large, occur frequently in axial locations and preferentially affect young patients. Unlike other primary bone sarcomas, Ewing sarcoma is radiosensitive and although use of radiation alone is associated with a higher local recurrence rate than resection,3, 9, 10 it is a viable treatment option, particularly in patients with metastatic disease. Studies to date have failed to determine whether patients with IPN on their staging chest CT should be treated in a similar manner to those with normal chest CTs or those with clear metastases. One difficulty is that no study has previously focused on Ewing sarcoma. For example, Cipriano et al. reported worse overall survival for patients with multiple pulmonary nodules of 5 mm or smaller compared with patients with normal chest CTs but this analysis only included 24 patients with Ewing sarcoma (out of 126) and the analysis pooled all bone and soft tissue sarcoma subtypes.14 This study is the first to our knowledge to address the prognostic significance of IPN in Ewing sarcoma and defines an IPN as a parenchymal lung nodule with a maximal diameter of 9 mm or less. Using this criteria and after eliminating patients with small benign nodules on their staging chest CT, we identified isolated IPN in only 8.7% of patients. An additional 5.2% of patients had IPN in combination with extra-pulmonary metastases and 23.7% had clear metastatic disease. We found that prognosis was comparable between IPN and ‘No Metastases’ patients; at two years post-diagnosis, overall survival was 73.3% and 89.4% respectively (p = 0.34). Both groups fared significantly better than those with skip or distant metastatic disease (two-year overall survival of 46.0%; p < 0.05 vs both groups). Though the number of IPN patients was small, this finding suggests that Ewing sarcoma patients with sub-centimetre nodules on their staging chest CT could be treated as aggressively as those with localized disease. Similarly, ‘No Metastases’ and ‘IPN’ patients had comparable metastasis-free survival (p = 0.161). In the IPN cohort, 40% developed metastatic disease during the follow-up period and disease progression occurred in a median of 9.6 months. This rate is comparable to reports in the literature.19,20 For instance, Mayo et al. found IPN in 33% of patients diagnosed with bone and soft tissue sarcomas, of which 31% progressed to clear metastases on follow-up. This group also investigated whether any demographic or oncologic variables correlated with metastatic progression and found an association with tumour size greater than 14 cm.20 In another study, Raciborska et al. followed 38 Ewing sarcoma patients with lung nodules of different sizes over time. They divided patients into four groups as per the Euro-Ewing Protocol: Group “0” was without nodules, Group “1” had a solitary nodule of <0.5 cm or several nodules of <0.3 cm, Group “2” had a solitary nodule of 0.5–1 cm or multiple nodules of 0.3–0.5 cm and Group “3” had one pulmonary/pleural nodule of >1 cm or more than one nodule of >0.5 cm. Twenty-three of the patients underwent thoracotomy and malignant cells were found in all nodules from Group “3”, 62.5% of patients in Group “2” and none in Group “1”.21 As the number of Ewing sarcoma patients with IPN on diagnosis was low, statistical analyses to explore whether any demographic, oncologic or CT characteristics correlated with overall- or metastasis-free survival were not feasible, however, several trends were apparent. First, as was noted by Raciborska et al., the presence of multiple bilateral IPN greater than 3 mm in diameter is suggestive of malignancy. Second, as opposed to findings in our prior study on osteosarcoma,18 metastatic disease is just as likely to develop in extra-pulmonary as in pulmonary sites. Finally, also in contrast to findings in osteosarcoma where IPN growth following neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a poor prognostic factor, this study suggests that in Ewing sarcoma, IPN improvement on chemotherapy reflects a malignant nodule.

This study has several limitations. First, data collection was retrospective and is consequently prone to selection bias. Second, while surgical procedures were performed at a single institution, chemotherapy and radiation are administered locally in the United Kingdom. As a result of the regional treatment, information regarding whole lung radiation and thoracotomy was incomplete. Furthermore, as patient follow-up can be shared between centres, some later chest CTs were not available for review. In these instances, the report of the local radiologist was utilized. While best efforts were made to obtain complete data sets for all patients, some gaps remained. Third, there is the potential for chronological variance as treatment decisions, particularly relating to surgical approach and indication for radiation, may have varied between 2008 and 2016 due to differences in available technologies and clinician preferences. Finally, chest CTs for patients without abnormalities on their staging exam were not re-reviewed as part of this study. Consequently, this may have resulted in an underestimation of the incidence of IPN.

5. Conclusion

This study is the first to examine the incidence and significance of indeterminate pulmonary nodules (IPNs) in Ewing sarcoma. We were unable to detect a difference in overall survival between patients that have IPN on their staging chest CT and those with normal chest imaging at diagnosis. While a larger study is required, this work suggests that when deciding on appropriate management of the primary tumour, IPN patients may be treated with curative intent.

Financial disclosures

No financial disclosures.

Declaration of competing interest

No conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcot.2020.12.018.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Albergo J.I., Gaston C.L., Laitinen M. Ewing’s sarcoma: only patients with 100% of necrosis after chemotherapy should be classified as having a good response. Bone Joint Lett J. 2016;98-B:1138–1144. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.98B8.37346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esiashvili N., Goodman M., Marcus R.B. Changes in incidence and survival of Ewing sarcoma patients over the past 3 decades: surveillance Epidemiology and End Results data. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30:425–430. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31816e22f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller B.J., Gao Y., Duchman K.R. Does surgery or radiation provide the best overall survival in Ewing’s sarcoma? A review of the National Cancer Data Base. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116:384–390. doi: 10.1002/jso.24652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paulussen M., Ahrens S., Burdach S. Primary metastatic (stage IV) Ewing tumor: survival analysis of 171 patients from the EICESS studies. European Intergroup Cooperative Ewing Sarcoma Studies. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:275–281. doi: 10.1023/a:1008208511815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosma S.E., Ayu O., Fiocco M., Gelderblom H., Dijkstra P.D.S. vol. 27. Elsevier; 2018. pp. 603–610. (Prognostic Factors for Survival in Ewing Sarcoma_ A Systematic Review. Surgical Oncology). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duchman K.R., Gao Y., Miller B.J. vol. 39. Elsevier Ltd; 2015. pp. 189–195. (Prognostic Factors for Survival in Patients with Ewing’s Sarcoma Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program Database. Cancer Epidemiology). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rissing S., Rougraff B.T., Davis K. Indeterminate pulmonary nodules in patients with sarcoma affect survival. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;459:118–121. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31805d8606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsoi K.M., Lowe M. How are indeterminate pulmonary nodules at diagnosis associated with survival in patients with high-grade osteosarcoma? Clin Orthop Rel Res. Elsevier Inc. 2017;169:750–757. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001491. e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DuBois S.G., Krailo M.D., Gebhardt M.C. Comparative evaluation of local control strategies in localized Ewing sarcoma of bone: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2014;121:467–475. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacci G., Ferrari S., Longhi A. Local and systemic control in Ewing’s sarcoma of the femur treated with chemotherapy, and locally by radiotherapy and/or surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85-B:107–114. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b1.12781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudeck O., Zeile M., Andreou D. Computed tomographic criteria for the discrimination of subcentimeter lung nodules in patients with soft-tissue sarcomas. J Clinical Imag. Elsevier Inc. 2011;35:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanamiya M., Aoki T., Yamashita Y., Kawanami S., Korogi Y. Frequency and significance of pulmonary nodules on thin-section CT in patients with extrapulmonary malignant neoplasms. European J Radiol. Elsevier Ireland Ltd. 2012;81:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brader P., Abramson S.J., Price A.P. Do characteristics of pulmonary nodules on computed tomography in children with known osteosarcoma help distinguish whether the nodules are malignant or benign? J Pediatr Surg. Elsevier Inc. 2011;46:729–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cipriano C., Brockman L., Romancik J. The clinical significance of initial pulmonary Micronodules in young sarcoma patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015;37:548–553. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh K.M., Lee L.H., Beckingsale T.B., Gerrand C.H., Rankin K.S. Indeterminate nodules in osteosarcoma: what’s the follow-up? British J Canc. Nature Publ Group. 2018;118:634–638. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callister M.E.J., Baldwin D.R. How should pulmonary nodules be optimally investigated and managed? Lung Canc. 2016;91:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McWilliams A., Tammemagi M.C., Mayo J.R. Probability of cancer in pulmonary nodules detected on first screening CT. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:910–919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsoi K.M., Lowe M., Tsuda Y. How are indeterminate pulmonary nodules at diagnosis associated with survival in patients with high-grade osteosarcoma? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001491. Publish Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Absalon M.J., McCarville M.B., Liu T., Santana V.M., Daw N.C., Navid F. Pulmonary nodules discovered during the initial evaluation of pediatric patients with bone and soft-tissue sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Canc. 2008;50:1147–1153. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayo Z., Kennedy S., Gao Y., Miller B.J. What is the clinical importance of incidental findings on staging CT scans in patients with sarcoma? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11999.0000000000000149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raciborska A., Bilska K., Rychłowska-Pruszyńska M. Management and follow-up of Ewing sarcoma patients with isolated lung metastases. J Pediatr Surg. Elsevier Inc. 2016;51:1067–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.