Abstract

Coccydynia is a disabling condition characterized by pain in the coccyx region of the spine. The first description of the disease was given in as early as 1859. Since then a number of theories have been proposed by various researchers to explain the pathogenesis of the disease. Treatment options for coccydynia include ergonomic adaptation, manual therapy, injections and surgery. Despite being identified as a disease as early as 18th century, several uncertainties with respect to the origin of pain, predisposing factors and treatment outcomes of a wide range of treatment options persist till date. The current narrative review presents various aspects of the disease including pathoanatomy, clinical presentation, radiological features and management options for the disease.

Keywords: Coccydynia, Coccygectomy, Surgical technique, Radiology, Complications, Narrative review

1. Introduction

Coccydynia is a disabling condition characterized by pain in the coccyx region of the spine. First used by Simpson in 1859, the word coccydynia is derived from two Greek words ‘coccyx’ and ‘dynia’ where ‘coccyx’ signifies the resemblance to a cuckoo’s beak and ‘dynia’ is a commonly using suffix for pain.1,2 Despite being identified as a disease as early as 18th century, several uncertainties with respect to the origin of pain, predisposing factors and treatment outcomes of a wide range of treatment options persist till date. The current narrative review presents various aspects of the disease including pathoanatomy, clinical presentation, radiological manifestations and management options.

2. Material and methods

An extensive literature search in various data bases such as PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane library was carried out with search terms including ‘coccydynia’, ‘coccygectomy’ and ‘complications’. The yielded citations were examined for relevance and duplication. Additionally, case reports, case series with less than 10 subjects and articles in languages other than English were also excluded. The articles were further organized based on pre-selected sub-headings such as ‘patho-anatomy’, ‘etiology’, ‘radiological features’ and ‘management’ and the necessary information was extracted.

3. Pathoanatomy

Coccyx is the terminal triangular bone of the spine composed of three to five segments with variable disc spaces. The cranial most segment of the coccyx articulates with the sacrum. The inter-coccygeal disc spaces, although usually fused (except the first inter-coccygeal joint which is usually segmented), have also been reported to contain intact discs, discs with clefts or fibro-fatty changes or even replaced with synovial joints.3,4 Therefore, along with sacro-coccygeal joint pathological mobility may also be seen in inter-coccygeal joints. The anterior surface is characterized by three or four fusion grooves serves as attachment for levator ani muscle and sacro-coccygeal ligaments. The posterior surface of the proximal most segment is marked by coccygeal cornua which articulates with the sacral cornua forming the posterior sacral foramina to provide an exiting track for the posterior division of the fifth sacral nerve. Anterior sacral foramen is formed by the two lateral processes of the caudal most sacral and cranial most coccygeal vertebra. The lateral surface of the coccyx provides attachment to sacro-spinous and sacro-tuberous ligaments and fibers of gluteus maximus muscle. The tip of the coccyx provides attachment to the ilio-coccygeus muscle which provides support to the pelvic floor and contributes to voluntary bowel continence mechanism.

4. Etiology

4.1. Trauma

The commonest etiology of coccydynia is external or internal trauma.5 Coccyx functions as the third leg of the tripod along with ischial tuberosities to provide support while sitting. However, this peculiar location makes it predisposed to injury in the setting of an external trauma such as a backward fall leading to an injury to the coccyx. Antecedent history of direct trauma has been found to be present in 50–65% of patients with coccydynia as reported in literature.3,6 Depending on the severity of the trauma, the injury may include a sprain of the pelvic floor muscles, mild distortion over a fissure in the caudal coccygeal segment, or a severe fracture-dislocation of the sacrococcygeal complex.7

Other less obvious sources of external trauma can include prolonged sitting on hard surfaces such as improperly cushioned wooden chairs. In 1950, Schapiro referred the disease as ‘television disease’ signifying an important role of postural adaptation as a predisposing factor for coccydynia.5 Apart from external trauma, internal trauma as experienced during a difficult or instrumented delivery may also lead to coccydynia.

4.2. Obesity and female gender

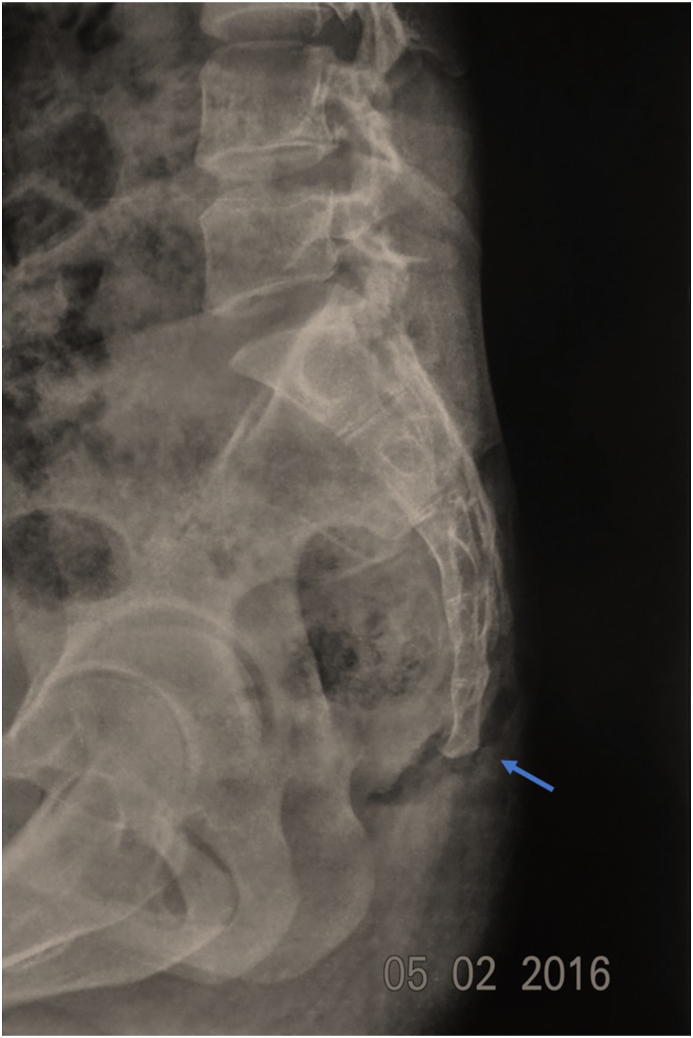

Both obesity and female sex are known to be predisposing factors for coccydynia. A BMI of over 27.4 in females and 29.4 in males was found to be a risk factor for both traumatic and non-traumatic coccydynia.8 The biomechanical basis of a higher incidence of coccydynia in association with obesity has been attributed to restricted sagittal pelvic rotation in obese individuals while sitting leading to protrusion, retroversion and excessive pressure over the tip of the coccyx.8 Additionally, increased intra-pelvic pressure during sitting may lead to posterior subluxation of the jutting out tip of the coccyx (Fig. 1). Females owing to the inherent ligamentous laxity, susceptible coccygeal morphology and child birth, were found to be five times more prone to develop coccydynia than men.6,9

Fig. 1.

Standing (left) and sitting (right) radiographs depicting the posterior subluxation at sacro-coccygeal joint in an obese patient.

4.3. Coccygeal morphology

The normal coccygeal morphology is highly variable. Postacchinni and Massobrio initially classified the morphological variants into four types to which two more types were further added by Nathan et al.7,10 (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

Type I – gentle ventral curvature with caudally pointed apex of the coccyx. Found in over 50% of population.

Type II – more prominent ventral curvature with apex pointing anteriorly. Found in 8–32% of the population.

Type III – Acute anterior angulation without subluxation. Found in 4–16% of the population.

Type IV – Subluxation at sacro-coccygeal or inter-coccygeal joint. Found in 1–9% of the population.

Type V – Retroverted with posteriorly angulated apex. Found in 1–11% of the population.

Type VI – Scoliotic or laterally subluxated coccyx. Found in 1–6% of the population.11

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of six morphological variants of coccyx as described in literature.

Fig. 3.

Radiographic depiction of six morphological variants of coccyx described in literature.

Type III to VI were found to have a significantly higher incidence in patients with coccydynia coccydynia whereas type II was found to have somewhat higher incidence in patients with coccydynia. Type I had a lesser incidence in patients with coccydynia when compared to normal subjects. Presence of a posterior spicule was found to be present in 14% of coccydynia patients and is known to be a significant factor in causing chronic adventitious bursitis due to irritation of soft tissues, especially in Type V coccyx8,12 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A type 1 coccyx with a posterior spicule (blue arrow).

4.4. Coccygeal hypermobility

A number of researchers have hypothesized coccydynia to be a dynamic condition rather than static.3,13,14 Abnormal coccygeal translation or angular motion has been found to be present in 69% of patients presenting with coccydynia as seen in dynamic standing and seated radiographs.15 Maigne et al. has classified coccygeal mobility into four types15:

-

1.)

Luxation – Posterior subluxation of the mobile segment of coccyx on assuming sitting posture. More commonly associated with obese individuals as a result of increased intra-pelvic pressure.

-

2.)

Hypermobility – Direct seating axial pressure leading to coccygeal flexion over 25°. More common cause of pain in thin individuals individually or in association with a spicule.

-

3.)

Immobile – Less than 5° of coccygeal flexion on sitting. May lead to coccydynia in isolation or with a posterior spicule

-

4.)

Normal – Coccygeal mobility of 5–25° on dynamic radiography.

4.5. Discogenic pain

Inter-coccygeal articulations are known to contain a number of variants of intervertebral disc as mentioned above. Degenerative changes in these discs or their variants have been incriminated to be a cause of pain in 41% of idiopathic and 44% of traumatic coccydynia.13 In a histological study comprising of 8 coccyges of patients undergoing coccygectomy, five were found to have degenerative disc changes and two were found to have degenerative articular cartilage changes.4 Maigne et al. in his experiments with provocative discography reported a positive result in 15 of 21 patients with coccydynia.3

4.6. Rare causes

A number of researchers have reported other rare causes of coccydynia such as tuberculosis, tumors such as chordoma, osteoid osteoma (Fig. 5), trichoblastic carcinoma or notochordal cell tumors and a few case reports have also reported excessive calcium salts deposition in inter-coccygeal or sacro-coccygeal articulations as a cause for coccydynia.16, 17, 18, 19 Although all these causes are extremely rare but a possibility of such a diagnosis should always be kept in mind.

Fig. 5.

Osteoid osteoma lesion at the last coccygeal segment, a rare cause of coccydynia.

4.7. Association with neurosis

A number of researchers have suggested neurotic origin of pain in patients with coccydynia.20, 21, 22 The association between coccydynia and neurosis was first pointed out by Bremmer.20 Later in 1959, Smith described a separate cohort of patients of coccydynia with associated neurotic and psychogenic disorders such as hysteria and obsessive-compulsive disorder.22 Even so with knowledge, any patient with coccydynia should be thoroughly evaluated for the underlying cause, and neurotic causes should only be a diagnosis of exclusion.

5. Clinical presentation

The clinical description of the disease was first given by Thiele and holds true till date.9 The patients usually experience a sharp shooting or sometimes an aching kind of pain in the lower sacral or coccygeal segments, especially while sitting on flat and hard surfaces. The severity of pain may range from mild and occasional pain to excruciating pain severe enough to adversely affect the activities of daily living. Pre-menstrual period in women is often associated with exaggeration of symptoms. Activities leading to increased strain on levator ani muscle such as defecation and sexual intercourse may also lead to exaggeration of symptoms in such patients.

6. Radiological features

Static imaging including radiographs, CT and MRI have been found to be inconclusive in a majority of patients with coccydynia.23 Nevertheless, lateral and AP radiographs constitute an important primary investigation to rule out infections, tumors or predisposed coccygeal morphology such as retroverted coccyx, a bony spicule, coccygeal scoliosis or subluxation (Fig. 6). In cases of trauma, where radiographs are suggestive of a fracture or dislocation, a CT scan is recommended for definitive diagnosis.

Fig. 6.

Antero-posterior and lateral radiographs with post-traumatic double subluxation at sacro-coccygeal and inter-coccygeal joints.

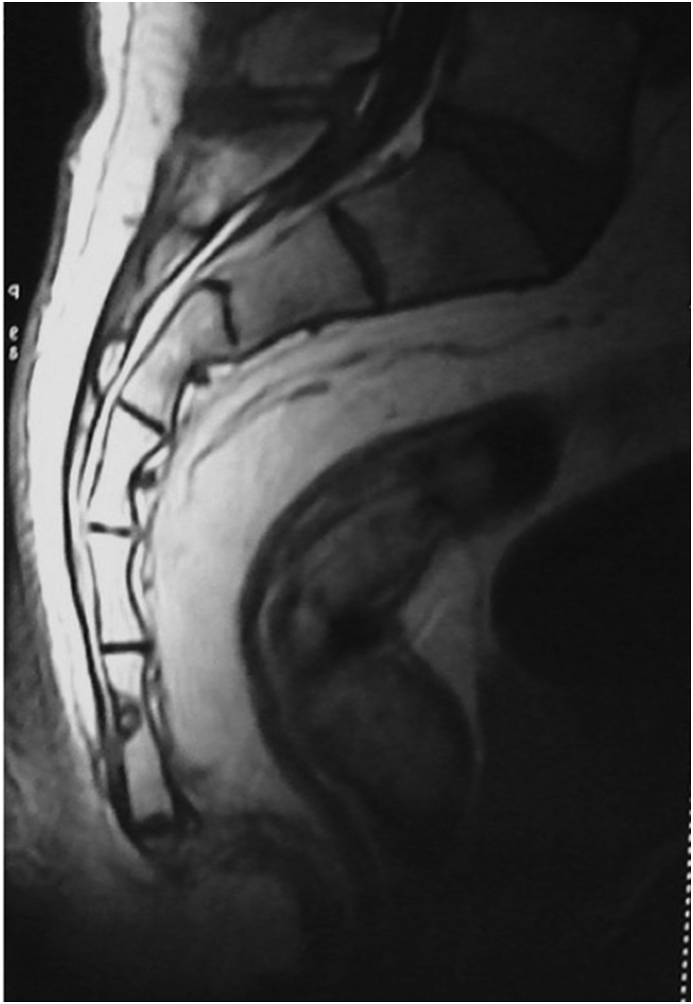

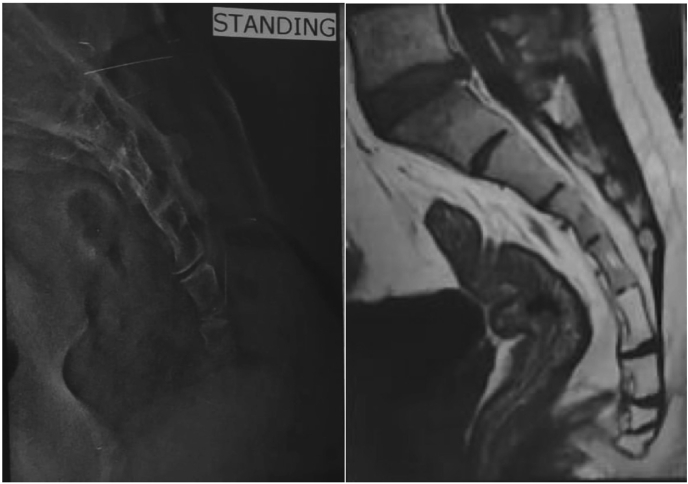

In patients with normal static imaging with radiographs and CT scans, dynamic imaging may be performed to rule out abnormal coccygeal mobility.24 Angular mobility more than 25° or less than 5° has been described as abnormal and may provide impetus to pain in coccydynia.15 Several methods have been described in literature to diagnose angular mobility, albeit without validation. Dynamic radiographs are performed in standing and seated position at the point of maximum pain during extension while being seated. Maigne described measurement of angular mobility by superimposing the dynamic radiographs and drawing a line joining the center of the last mobile segment to the tip of the coccyx and measuring the difference between the two angles in the superimposed films3,8,15 (Fig. 7). Suk and Kim have described inter-coccygeal angle as the angle between two lines drawn parallel and bisecting the first and last segment of coccyx.11 This technique may be further extrapolated for measuring angular mobility; however, such a technique has not been described for dynamic imaging till date. Coccygeal mobility may also be evaluated by comparing erect lateral radiographs with supine MR films (Fig. 8). Nevertheless, due to the lack of validated techniques for the measurement of angular mobility dynamic imaging is not widely popularized as an imaging modality in these patients, and while recommended, it is not standardized.

Fig. 7.

Schematic diagram depicting the measurement of coccygeal mobility.

Fig. 8.

Coccygeal mobility assessment using standing radiograph(left) and supine MRI (right).

MRI is useful to identify areas of signal alteration in and around the coccyx to identify the site of origin for pain. Areas of T2 hyperintensity with low to intermediate T1 signals suggestive of Modic type 1 changes are commonly encountered in patients with chronic coccydynia, more so in patients with sub-luxation and hypermobility.23 Balain et al. demonstrated degenerative changes in histological samples of patients undergoing coccygectomy with signal alterations on MRI imaging. Additionally, MRI may also be able to diagnose chronic irritation and bursitis as edema on the tip of coccyx or soft tissue posteriorly. Grassi et al. analyzed coccygeal movement during defecation using dynamic MRI and reported a significantly higher normal motion than that reported by Maigne, suggesting a higher range of normal motion of coccyx during defecation than during sitting position.25

7. Treatment

A wide variety of treatment options have been described in literature for the management of coccydynia. The treatment strategies may be classified as follows:

-

1.)

Ergonomic adaptation – Doughnut or ring-shaped pillows, posture training, buttock strapping and stool softening measures.

-

2.)

Manual or physical therapy – Manipulation of coccyx and massage of the levator ani (pelvic floor muscles).

-

3.)

Injections and nerve block – Steroid or anesthetic injections, prolotherapy and ganglion impar block.

-

4.)

Surgery – coccygeoplasty or partial or complete coccygectomy.

Conservative therapy is successful in 90% of the patients suffering from coccydynia.14,26,27 Ergonomic adaptations as described above with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications are the first modalities to be employed for the management. However, evidence supporting their use is sparse. Manual therapy is commonly performed by chiropractors or physical therapists and is reported to have a good success rate.28, 29, 30 Manual therapy is composed of two basic components – massage and manipulation. Massage further can be performed externally over the peri-coccygeal region or internally per rectally. Thiele described the pathogenesis of pain generation in coccydynia and described a pivotal role of levator ani spasm.9 Spasm of coccygeus further aggravates sacro-coccygeal joint pain and degeneration which in turn leads to more spasm. Thus, massaging the long fibers of levator ani plays a role in relieving the muscles of spasm and break the vicious pain cycle.9 However, Maigne described a different subset of patients with abnormal mobility of coccyx where spasm was not significant, and therefore, massage therapy showed poor results. He recommended coccygeal manipulation in these patients.31 Mennell described the technique of manipulation with the finger inside the rectum and thumb outside for grasping the coccyx.32 Further, coccygeal extension should be maintained after manipulation for a few minutes by applying backward pressure over the coccyx and inferior sacrum using index finger and counter-pressure over the sacrum using the opposite hand.31

For cases refractory to conservative treatment, steroid and anesthetic injections constitute the second line of management. Several researchers have employed injections with successful outcomes.24,33,34 Injections may be useful as both treatment and a diagnostic modality to predict outcomes after coccygectomy. However, the site of injection is controversial and lacks reasonable quality of literature to reach a conclusion. Nevertheless, sacro-coccygeal and intercoccygeal joints, tender point and ganglion impar are the common injection sites cited in literature.33,34 CT-guided ganglion impar block has been shown to have a success rate of 75% at 6 months follow up.34 A few researchers have also recommended ablative therapy in recurrent cases.35,36 Additionally, neuro-modulation and spinal cord stimulation in the conus region from L2-S2, has also been shown to be successful for persistent and severe perineal pain.36,37 Dextrose prolotherapy has also been reported as an effective treatment modality for recurrent coccydodynia. Khan et al. reported a successful outcome in 30 of 37 patients of recalcitrant coccydodynia undergoing dextrose prolotherapy with 25% dextrose injection.38

Failure of all conservative methods and injections is an indication for surgical removal of coccyx also known as coccygectomy. Several case series have reported good to excellent outcomes following coccygectomy.39, 40, 41, 42 However, technical difficulties and high chances of infection owing to the location of the incision close to the anal canal makes the surgery and follow-up care challenging.

Coccygectomy is commonly performed via a posterior midline incision as described by Key in 1937.43 A recent modification described by Kulkarni et al. adds a Z-plasty to the incision in order to reduce the tension and centrifugal forces acting on the incision, and therefore reducing the incidence of wound related complications.41 The dissection proceeds with a sacro-coccygeal discectomy from cranial to caudal direction as described by Key to avoid an injury to the rectum, especially in anteverted coccyx; however, some surgeons have described the release of ano-coccygeal ligament first followed by elevating the distal end of the coccyx.13,41 The amputation can be done at or slightly proximal to the sacro-coccygeal junction. Sacro-coccygeal junction can be identified by the cornuate articulation posteriorly. The anterior sub-periosteal dissection is extremely crucial to prevent injury to the rectum followed by en-block removal of coccyx. Hemostasis and a double layered closure are extremely crucial to reduce the chances of infection. Finally, a cushioned dressing well separated and sealed from the anal region should be applied to avoid contamination. The author’s technique of coccygectomy has been depicted in Video 1. The authors recommend a 3 cm curvilinear incision with the coccyx in the center identified using image intensifier. The purpose of a curvilinear incision is to the off-load of the suture line and prevent wound related complications. After manual palpation, the coccyx is skeletonized with the help of monopolar and bipolar cautery and periosteal elevators. The sacro-coccygeal or the last mobile segment is identified and osteotomized. Further, dissection is continued in a cranial to caudal direction with an aim to deliver the resected coccyx en bloc. A special emphasis is given to the dissection on the ventral side of the coccyx. The authors recommend using periosteal elevators instead of cautery to avoid injury to rectum and other vital pelvic structures.

The complication rate following coccygectomy ranges from 0 to 50%.44 Common complications following coccygectomy include infection and wound related complications including wound dehiscence and delayed healing. Doursounian et al. in their comparative study showed the decrease in infection rate to 0% by using skin adhesive, 2 prophylactic antibiotics for 48 h, preoperative rectal enema, and closure of the incision in 2 layers as compared with infection rate of 1.5% with the use of topical skin adhesive alone.45 Other rarer complications include incomplete excision of coccyx and much sinister rectal injuries.

Supplementary video related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcot.2020.09.025

The following is/are the supplementary data related to this article:

Multimedia component 1

8. Functional outcome

Conservative management with lifestyle modifications and NSAIDs constitute the mainstay of management in coccydynia. Wray et al. in their article reported 60% relief with injections, 85% with manipulation and massage and 90% improvement following coccygectomy.46 Similar results were reported by Perkins et al. and Ramsey et al. They reported 75% and 78% improvement with manipulation and injection and 92% and 87% improvement respectively.47,48 Over-all improvement in symptoms following coccygectomy range from 85 to 100% in literature.41,44,45,47,48

9. Conclusion

Patients with coccydynia suffer a lot of stigma due to ignorance of the underlying etiology and association of neurotic symptoms in some patients. A thorough search for the underlying etiology is paramount to obtain optimum results. The management of coccydynia should be carried out in a step-wise approach with increasing invasiveness. Finally, for resistant and recalcitrant cases, coccygectomy has shown excellent medium to long term outcomes.

Funding source

Nil.

References

- 1.Simpson J. Clinical lectures on the diseases of women Lecture XVII: coccydynia and diseases and deformities of the coccyx. Med Times Gaz. 1859;(40):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugar O. Coccyx. The bone named for a bird. Spine. 1995;20(3):379–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maigne J.Y., Guedj S., Straus C. Idiopathic coccygodynia. Lateral roentgenograms in the sitting position and coccygeal discography. Spine. 1994;19(8):930–934. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199404150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balain B., Eisenstein S.M., Alo G.O. Coccygectomy for coccydynia: case series and review of literature. Spine. 2006;31(13):E414–E420. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000219867.07683.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schapiro S. Low back and rectal pain from an orthopedic and proctologic viewpoint; with a review of 180 cases. Am J Surg. 1950;79(1):117–128. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(50)90202-9. illust. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pennekamp P.H., Kraft C.N., Stütz A., Wallny T., Schmitt O., Diedrich O. Coccygectomy for coccygodynia: does pathogenesis matter? J Trauma. 2005;59(6):1414–1419. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000195878.50928.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nathan S.T., Fisher B.E., Roberts C.S. Coccydynia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92-B(12):1622–1627. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B12.25486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maigne J.Y., Doursounian L., Chatellier G. Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. Spine. 2000;25(23):3072–3079. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiele G.H. COCCYGODYNIA: cause and treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1963;6:422–436. doi: 10.1007/BF02633479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Postacchini F., Massobrio M. Idiopathic coccygodynia. Analysis of fifty-one operative cases and a radiographic study of the normal coccyx. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65(8):1116–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim N.H., Suk K.S. Clinical and radiological differences between traumatic and idiopathic coccygodynia. Yonsei Med J. 1999;40(3):215–220. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1999.40.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dennell L.V., Nathan S. Coccygeal Retroversion Spine. 2004;29(12):E256–E257. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000127194.97062.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayne O., Bateman J.E., Cameron H.U. The influence of etiology on the results of coccygectomy. Clin Orthop. 1984;190:266–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogel G.R., Cunningham P.Y., Esses S.I. Coccygodynia: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12(1):49–54. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maigne J.Y., Lagauche D., Doursounian L. Instability of the coccyx in coccydynia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(7):1038–1041. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.82b7.10596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blocker O., Hill S., Woodacre T. Persistent coccydynia--the importance of a differential diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1136/bcr.06.2011.4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mechri M., Riahi H., Sboui I., Bouaziz M., Vanhoenacker F., Ladeb M. Imaging of malignant primitive tumors of the spine. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2018;102(1):56. doi: 10.5334/jbsr.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coyer F., Miles S., Gosley S. Pressure injury prevalence in intensive care versus non-intensive care patients: a state-wide comparison. Aust Crit Care Off J Confed Aust Crit Care Nurses. 2017;30(5):244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCallum I.J.D., King P.M., Bruce J. Healing by primary closure versus open healing after surgery for pilonidal sinus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336(7649):868–871. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39517.808160. BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bremmer I. The knife for coccydynia: a failure. Med Recapitulate. 1896;50(154):5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dittrich R.J. Coccygodynia as referred pain. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1951;33-A(3):715–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith W.T. Levator spasm syndrome. Minn Med. 1959;42(8):1076–1079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skalski M.R., Matcuk G.R., Patel D.B., Tomasian A., White E.A., Gross J.S. Imaging coccygeal trauma and coccydynia. Radiographics. 2020;40(4):1090–1106. doi: 10.1148/rg.2020190132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maigne J.Y., Tamalet B. Standardized radiologic protocol for the study of common coccygodynia and characteristics of the lesions observed in the sitting position. Clinical elements differentiating luxation, hypermobility, and normal mobility. Spine. 1996;21(22):2588–2593. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199611150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grassi R., Lombardi G., Reginelli A. Coccygeal movement: assessment with dynamic MRI. Eur J Radiol. 2007;61(3):473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Capar B., Akpinar N., Kutluay E., Müjde S., Turan A. [Coccygectomy in patients with coccydynia] Acta Orthop Traumatol Turcica. 2007;41(4):277–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trollegaard A.M., Aarby N.S., Hellberg S. Coccygectomy: an effective treatment option for chronic coccydynia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92-B(2):242–245. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B2.23030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Origo D., Tarantino A.G., Nonis A., Vismara L. Osteopathic manipulative treatment in chronic coccydynia: a case series. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2018;22(2):261–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seker A., Sarikaya I.A., Korkmaz O., Yalcin S., Malkoc M., Bulbul A.M. Management of persistent coccydynia with transrectal manipulation: results of a combined procedure. Eur Spine J Off Publ Eur Spine Soc Eur Spinal Deform Soc Eur Sect Cerv Spine Res Soc. 2018;27(5):1166–1171. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5399-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott K.M., Fisher L.W., Bernstein I.H., Bradley M.H. The treatment of chronic coccydynia and postcoccygectomy pain with pelvic floor physical therapy. Pharm Manag PM R. 2017;9(4):367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maigne J.-Y., Chatellier G., Faou M.L., Archambeau M. The treatment of chronic coccydynia with intrarectal manipulation: a randomized controlled study. Spine. 2006;31(18):E621–E627. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000231895.72380.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mennel J.B. vol. III. Churchill; 1952. (The Science and Art of Joint Manipulation). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitra R., Cheung L., Perry P. Efficacy of fluoroscopically guided steroid injections in the management of coccydynia. Pain Physician. 2007;10(6):775–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Datir A., Connell D. CT-guided injection for ganglion impar blockade: a radiological approach to the management of coccydynia. Clin Radiol. 2010;65(1):21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agarwal-Kozlowski K., Lorke D.E., Habermann C.R., Am Esch J.S., Beck H. CT-guided blocks and neuroablation of the ganglion impar (Walther) in perineal pain: anatomy, technique, safety, and efficacy. Clin J Pain. 2009;25(7):570–576. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181a5f5c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Usmani H., Dureja G.P., Andleeb R., Tauheed N., Asif N. Conventional radiofrequency thermocoagulation vs pulsed radiofrequency neuromodulation of ganglion impar in chronic perineal pain of nononcological origin. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2018;19(12):2348–2356. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnx244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giordano N.L., van Helmond N., Chapman K.B. Coccydynia treated with dorsal root ganglion stimulation. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2018;2018:5832401. doi: 10.1155/2018/5832401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khan S.A., Kumar A., Varshney M.K., Trikha V., Yadav C.S. Dextrose prolotherapy for recalcitrant coccygodynia. J Orthop Surg Hong Kong. 2008;16(1):27–29. doi: 10.1177/230949900801600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soliman A.Y., Abou El-Nagaa B.F. Coccygectomy for refractory coccydynia: a single-center experience. Interdiscip Neurosurg. 2020;21:100735. doi: 10.1016/j.inat.2020.100735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kerr E.E., Benson D., Schrot R.J. Coccygectomy for chronic refractory coccygodynia: clinical case series and literature review: clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14(5):654–663. doi: 10.3171/2010.12.SPINE10262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kulkarni A.G., Tapashetti S., Tambwekar V.S. Outcomes of coccygectomy using the “Z” plasty technique of wound closure. Global Spine J. 2019;9(8):802–806. doi: 10.1177/2192568219831963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antoniadis A., Ulrich N.H.-B., Senyurt H. Coccygectomy as a surgical option in the treatment of chronic traumatic coccygodynia: a single-center experience and literature review. Asian Spine J. 2014;8(6):705–710. doi: 10.4184/asj.2014.8.6.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Key J.A. Operative treatment OF coccygodynia. JBJS. 1937;19(3):759–764. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kwon H.D., Schrot R.J., Kerr E.E., Kim K.D. Coccygodynia and coccygectomy. Korean J Spine. 2012;9(4):326–333. doi: 10.14245/kjs.2012.9.4.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doursounian L., Maigne J.-Y., Faure F., Chatellier G. Coccygectomy for instability of the coccyx. Int Orthop. 2004;28(3):176–179. doi: 10.1007/s00264-004-0544-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wray C., Easom S., Hoskinson J. Coccydynia. Aetiology and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73-B(2):335–338. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B2.2005168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perkins R., Schofferman J., Reynolds J. Coccygectomy for severe refractory sacrococcygeal joint pain. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16(1):100–103. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200302000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramsey M.L., Toohey J.S., Neidre A., Stromberg L.J., Roberts D.A. Coccygodynia: treatment. Orthopedics. 2003;26(4):403–405. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20030401-18. discussion 405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multimedia component 1