Abstract

Poor practice environments contribute to burnout, but favorable environments containing support, resources, autonomy, and optimal relations with colleagues may prevent burnout. Compared to all nurse practitioners (NPs), 69% of these NPs provide primary care to patients, yet it is unknown whether the practice environment is associated with NP burnout. A study to examine environmental factors related to NP burnout was conducted. Overall, 396 NPs completed the survey and 25.3% were burnt-out. Higher scores on the professional visibility, NP-physician relations, NP-administration relations, independent practice and support subscales were associated with 51%, 51%, 58%, and 56% lower risk of NP burnout, respectively.

Keywords: Primary Health Care, Nurse Practitioners, Practice Environment, Burnout, Organization and Administration

Introduction

Clinician burnout is recognized by feelings of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment.1 Nearly 35% of nurses are burnt-out2 and 58.2% of hematology/oncology nurse practitioners experience moderate to high emotional exhaustion,3 which is a component of burnout. Given the high prevalence of burnout and the negative consequences (e.g., lower provider productivity, lower patient satisfaction, poor self-care, and provider turnover) resulting from burnout,4 researchers have classified burnout as a public health crisis.5

To date, researchers have found that a poor practice environment within the health care setting is a predictor of clinician burnout.5,6 For example, poor practice environments characterized by low autonomy to make patient care decisions, multiple job demands, and limited support from administrators leads to nurse burnout.6 In a meta-analysis, hospital nurses in favorable work environments, characterized by adequate staffing and resources, collegial relations between nurses, physicians and administrators, and visibility of nurses on important committees, had 26% lower odds of burnout,7 thus indicating that the environment where nurses deliver patient care can influence burnout. However, little attention has been given to burnout among primary care providers (PCPs) including physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants. This is a problem because research conducted in acute care facilities with hospital nurses cannot be generalized to PCPs in the primary care setting. Given that much of health care is provided by clinicians in primary care practices,8 the investigation of clinician burnout in the primary care setting is crucial.

Rates of PCP burnout have ranged from 22.6% to 25.1%,9 and researchers report that poor practice environments are one of the most common modifiable predictors of burnout.9–13 Yet, of the studies investigating burnout among PCPs, several explore primary care physician burnout.11,12,14 As a result, the prevalence and factors associated with burnout among other types of PCPs, specifically NPs, remains greatly understudied.

Currently, of all NPs, 69% of NPs deliver primary care services to patients,15 and by 2030 it is projected that NPs will comprise about one-third of all PCPs.16 Primary care NPs are nurses with additional training at the Masters or Doctoral level and can assess, diagnose, and manage patient conditions, order and interpret tests, prescribe medications, and provide patient education.17 Compared to other PCPs, NPs are more likely to practice in low-income, high-minority practices18,19 which generally have limited resources needed for patient care.20 Furthermore, 46.1% of NPs reported working in a poor practice environment,21 and in another study, one in every four NP felt that their role was not well-understood by practice administrators.22 In addition, only 39.5% of NPs reported that practice administrators treated NPs and physicians equally,22 suggesting that possibly more than half of the NPs felt otherwise. Moreover, NPs in poor practice environments had limited administrative support and resources, strained relations with physicians, poor communication with staff, and limited independence.23 As a result, challenges within the primary care practice environment may predispose NPs to burnout.

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to assess burnout among primary care NPs and investigate whether the primary care NP practice environment is associated with NP burnout.

Methods

Conceptual Framework

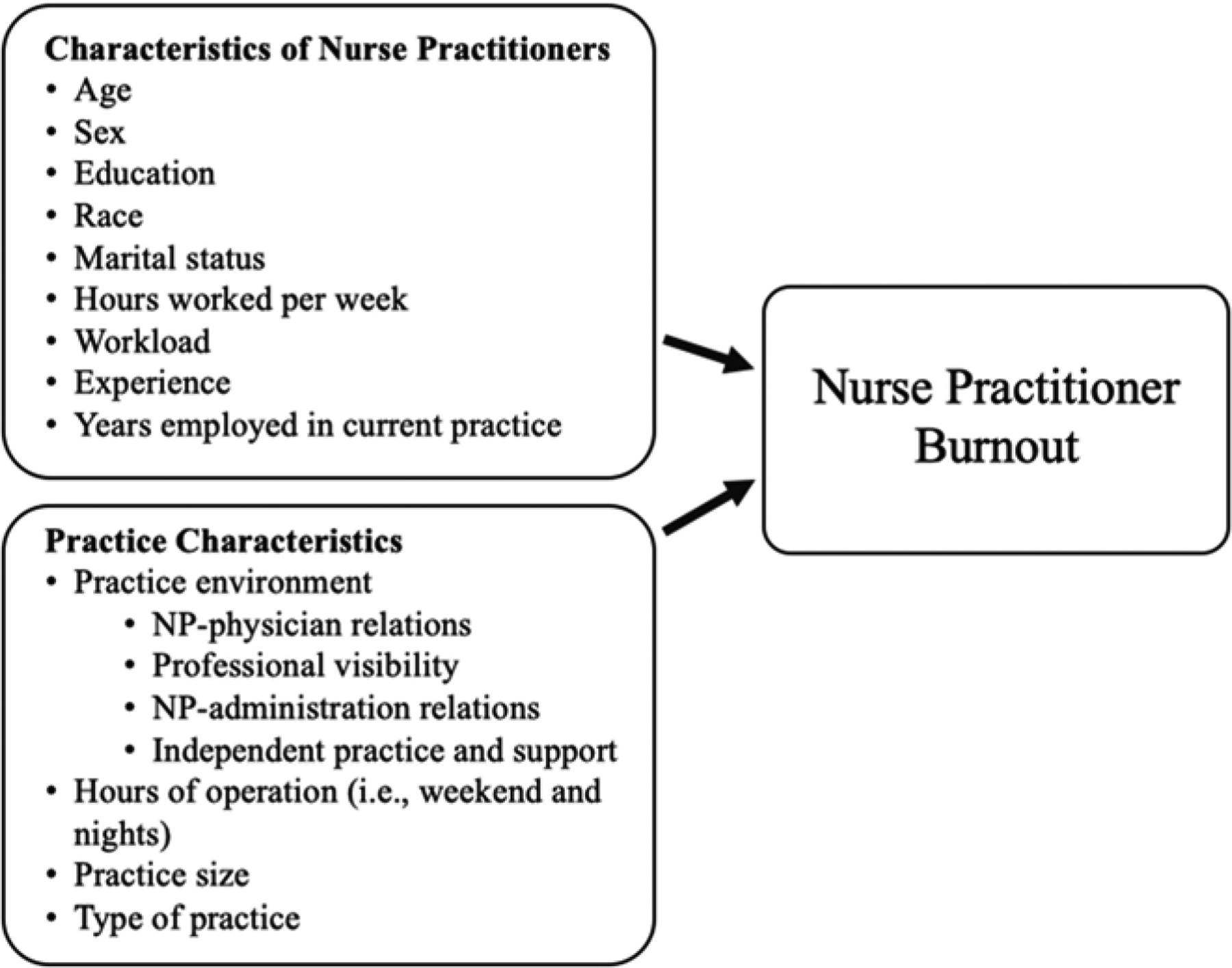

The Clinician Well-Being and Resilience model24 guided this study. The model was developed by researchers at the National Academy of Medicine and illustrates the relationship between individual and external factors affecting clinician well-being including burnout, and potential consequences of burnout.24 We adapted the model to focus specifically on the relationship between primary care NP practice environment, burnout, NP demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex, education, race, marital status, hours worked per week, years of NP experience, workload, and years employed in the current practice), and characteristics of the primary care practice (i.e., size, hours of operation, and type of practice) (Figure 1). Our adapted framework is reliable because it illustrates the relationship among variables that may potentially influence PCP burnout and such relationships were supported by the literature.9,10,13

Figure 1.

Adapted Clinician Well-Being and Resilience model

Note. NP = Nurse Practitioner;

Study Design and Data Source

This study is a secondary analysis of cross-sectional survey data obtained from a large study25 focused on health disparities for older adults with chronic conditions receiving primary care services from NPs. This dataset was chosen because it is the only dataset that currently exists containing valid measures of NP burnout, practice environment, and variables measuring demographic characteristics of NPs and their main practice site specifically in the primary care setting.

Parent study

Participants & Setting:

Researchers from the parent study discerned primary care NPs from the SK&A OneKey primary care practice database which contains information on practicing primary care NPs.26 NPs practicing in any one of the following three types of primary care practices were included; 1) an independent solo practice with the physician specializing in primary care and a minimum of one NP working in that practice, 2) a medical group practice where the whole practice focuses on primary care and a minimum of one NP working in that practice, or 3) a medical group practice employing one or more physician and which has at-least half of the physicians specializing in primary care with a minimum of one NP working in that practice. Considering that there were more NPs in larger states (i.e., California, Texas, and Pennsylvania) than in smaller states (i.e., Washington, New Jersey, and Arizona), researchers used a random sample of NPs to create comparable counts of NPs across the states included in the sample.

Data Collection:

In the parent study, primary care NPs completed surveys asking about their practice environment, burnout, demographics, and characteristics of their main practice site. Using a modified Dillman approach for mixed-mode surveys,27 researchers sent NPs mailed surveys which also contained an online link to enable NPs to complete the surveys electronically or by paper. In total, three rounds of mailed questionnaires and two postcard reminders were sent to non-responding NPs. To increase the overall response rate, researchers conducted follow up calls to non-responding NPs. In the follow up calls, it was determined that some NPs were ineligible because they never worked or no longer worked in the practice. Other NPs were labeled as “unknown” because, despite researchers calling those practices three separate times, no one answered to allow researchers to verify NP eligibility. Ultimately, 1,244 NPs completed the survey. Response rates were determined using three different scenarios. In one scenario, it was assumed that all non-responding NPs were eligible and this resulted in the most conservative response rate of 22.2%. In a second scenario, it was assumed that almost half of the “unknown,” non-responding NPs were ineligible, and this resulted in a 25.7% response rate. In the third scenario, it was assumed that all of the non-responding NPs were ineligible, resulting in a 31.8% response rate. Thus, the true response rate may range from 22.2% to 31.8%.

Present Study

From the parent study, we were able to see variations in NP responses across different geographic regions and states with varying scope of practice regulations. Additionally, the parent study afforded us a unique opportunity to explore, using valid, commonly used measures, primary care NP burnout in two states with similar scope of practice regulations. For our secondary data analysis, we had a final sample of 396 primary care NPs practicing in either New Jersey or Pennsylvania. These two states, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, were chosen because they have comparable measures of access to care28 and quality of care29 and so NPs practicing in these two states would be working in comparable health care markets. Approval from the institutional review board of a large university located in the Northeast was received prior to conducting this study.

Measures

Practice Environment:

To measure the practice environment, the Nurse Practitioner Primary Care Organizational Climate Questionnaire (NP-PCOCQ) was used.30 The NP-PCOCQ is a 29-item survey which has four subscales measuring the following domains: NP-Physician Relations (NP-PR), Professional Visibility (PV), NP-Administration Relations (NP-AR), and Independent Practice and Support (IPS).30 The NP-PR subscale (7 items) measured the degree of teamwork between NPs and physicians, and it also measured whether physicians trust the decisions made by NPs regarding patient care. The PV subscale (4 items) measured the clarity and visibility of the NP role within their practice. The NP-AR subscale (9 items) measured NP’s perception of relations with administrators from their practice, and the IPS subscale (9 items) measured the availability of resources and support NPs have in their practice, whether the organization creates an environment where NPs can practice independently, and whether the organization restricts NP ability to practice within their scope of practice.30 The NP-PCOCQ is widely used31–33 and has strong psychometric properties. This tool has been tested for content, construct, structural, discriminant, and predictive validity.30 In this present sample of primary care NPs from New Jersey and Pennsylvania, the Cronbach’s alpha for the NP-AR subscale was 0.94, the NP-PR subscale was 0.88, the PV subscale was 0.85, and the IPS subscale was 0.87.

The NP-PCOCQ uses a 4-point Likert scale that ranges from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”30 Higher mean subscale scores for each individual NP-PCOCQ subscale indicated better primary care NP practice environments. Since the practice environment is a shared perception held by NPs, organizational level scores were generated by aggregating the individual practice environment scores of NPs in the same practice for each of the four NP-PCOCQ subscales.

Burnout:

Primary care NP burnout, as the dependent variable, was measured using a non-proprietary, single item measure.34 This non-proprietary single item burnout measure is widely used in studies investigating PCP burnout.9,11–13 For our study with 396 primary care NPs from New Jersey and Pennsylvania, which were obtained from the parent study, NPs self-reported their level of burnout from one (I enjoy my work. I have no symptoms of burnout) to five (I feel completely burned-out and often wonder if I can go on). A higher score indicated greater burnout.34 For the ease of interpretation, we dichotomized responses so that scores ranging from three to five were combined to indicate “burnout,” and scores one to two were combined to indicate “no burnout.” This dichotomization of the burnout variable has been commonly used in prior studies investigating PCP burnout.9,13

Covariates:

We retrieved data on characteristics of NPs (i.e., age, sex, race, education, marital status, workload, years employed in current practice, number of hours worked per week, and years of NP experience), characteristics of the main practice site (i.e., size, hours of operation, and type of primary care practice), and geographical location (i.e., state).

Statistical Analysis

All data were cleaned and coded in SPSS statistical software.35 The distribution of continuous variables was inspected for outliers using boxplots and any outlier values from the dataset were removed. We used the variance inflation factor (VIF) statistics to check for multicollinearity, and VIF values less than five suggested lack of multicollinearity.36 After conducting a power analysis, it was determined that 280 NPs was the minimal sample size needed for this study.

Multiple Imputation:

Given that certain variables in our study had up to 12% of missing observations, we used multiple imputation analyses because it is a methodologically rigorous approach to handling missing data and it is recommended over traditional techniques such as mean substitution.37,38 We created 10 simulated versions of the dataset based on the percentage of missing data.39 Those datasets were analyzed, combined, and adjusted to generate pooled results which represented the aggregated scores from the 10-simulated versions of the dataset.37,38 We extracted and imported the pooled dataset into STATA statistical software.40

Multi-level Analyses:

We ran four multi-level cox regression models which are more appropriate than logistic regression models because logistic regression models using odds ratios may overestimate the results when the prevalence of an outcome (e.g., NP burnout) is more than 10%.41 We created a constant time variable because in this cross-sectional study, we only had NP responses during one time-point with burnout rates reported once-not during various time intervals. Although cox regression proportional hazard models, which incorporate results from various time intervals, generate a hazard ratio,42 having a time variable that is constant makes the value of the hazard ratio similar to the risk ratio,41,42 because hazard ratio is risk of an event divided by time but with time being constant, the ratio of the two hazards becomes the ratio of two risks which is the risk ratio. Thus, throughout this study, we use the term “risk ratio” (RR) instead of “hazard ratio.” To illustrate the strength and direction of the relationship between the four NP-PCOCQ practice environment subscales and burnout, we reported the 95% confidence intervals (CI), the p-values, and the RRs. The four multi-level cox regression models include NP-level demographic variables in level one of the model as well as survey modality (i.e. mail or online), and NP burnout. Variables measuring the practice environment, practice size, main practice site, and hours of operation were practice-level variables within level two of the model. We included state as a fixed-effect variable.

Results

This study used data from 396 NPs, with 27.5% of NPs being from New Jersey and the rest from Pennsylvania (Table 1). Most NPs were female (90.4%) and White (89.4%). The average age of these NPs was 49.5 years (Standard Deviation [SD] = 12.0 years). Only 3% of NPs had a PhD or other doctorate as their highest educational degree, 7.1% held a Doctorate of Nursing Practice (DNP), and 87.6% had a Master’s degree. On average, NPs worked 38.9 hours per week (SD = 11.2) with most of their time spent on providing direct clinical patient care, followed by coordinating patient care. Most primary care NPs (60.4%) practiced in a physician-owned clinic. The practice-level scores on the NP-PCOCQ subscales ranged from 2.82 (SD = 0.71) on NP-AR to 3.42 (SD = 0.48) on IPS. The PV subscale was 3.11 (SD = 0.65), and 3.33 (SD = 0.52) for the NP-PR subscale.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Primary Care Nurse Practitioners and their Practices

| N (%) | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 49.5 years (12.0) | |

| Female | 358 (90.4) | |

| Highest Educational Degree | ||

| Master’s degree | 347 (87.6) | |

| Doctorate of Nursing Practice (DNP) | 28 (7.1) | |

| PhD or other doctorate | 12 (3.0) | |

| Other | 9 (2.3) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 354 (89.4) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 12 (3.0) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 315 (79.5) | |

| Years of NP experience | 11.4 years (8.9) | |

| Years employed in current practice | 6.4 years (6.3) | |

| Average number of hours worked per week | 38.9 hours (11.2) | |

| NP workload | ||

| Providing direct patient care | 31.1 hours (10.1) | |

| Coordinating patient care | 5.6 hours (6.0) | |

| Providing care management services | 2.0 hours (3.3) | |

| Performing quality assurance and improvement activities | 1.6 hours (3.5) | |

| Conducting administrative activities/leadership | 1.7 hours (3.9) | |

| Survey Modality | ||

| 309 (78.0) | ||

| Online | 87 (22.0) | |

| Burnout | 100 (25.3) | |

| Characteristics of Primary Care Practices | ||

| Practice Location | ||

| New Jersey | 109 (27.5) | |

| Pennsylvania | 287 (72.5) | |

| Main practice site | ||

| Physician practice | 239 (60.4) | |

| Community health center | 51 (12.9) | |

| Hospital based clinic | 37 (9.3) | |

| Retail-based clinic | 8 (2.0) | |

| Urgent care clinic | 12 (3.0) | |

| Nurse managed clinic | 4 (1.0) | |

| Other | 45 (11.4) | |

| Practice Open on Weekends | 141 (35.6) | |

| Practice Open at Night | ||

| None | 127 (32.1) | |

| Once a week | 78 (19.7) | |

| Twice a week | 82 (20.7) | |

| Three times a week | 24 (6.1) | |

| Four or more times a week | 85 (21.5) | |

| Primary Care NP Practice Environment Scores | ||

| Professional Visibility | 3.11 (0.65) | |

| NP-Administration Relations | 2.82 (0.71) | |

| NP-Physician Relations | 3.33 (0.52) | |

| Independent Practice and Support | 3.42 (0.48) | |

Note. SD = Standard Deviation; NP = Nurse Practitioners;

Overall, 25.3% of NPs were burnt-out. Multicollinearity was not discovered in any of the final multi-level cox regression models (mean VIF = 1.70). In our multi-level models in which time was a constant variable (Table 2), higher PV subscale scores were associated with 51% lower risk of NP burnout (RR = .49, 95% CI = .36 to .66, p = .00). Similarly, higher NP-PR subscale scores were associated with 51% lower risk of NP burnout (RR = .49, 95% CI = .34 to .71, p = .00). Higher NP-AR subscale scores were associated with 58% lower risk of NP burnout (RR = .42, 95% CI = .31 to .56, p = .00), and higher IPS subscale scores were associated with 56% lower risk of NP burnout (RR = .44, 95% CI = .29 to .65, p = .00), after controlling for provider and practice level characteristics.

Table 2.

Results of multi-level cox regression models, with time as a constant variable, assessing the association between practice environment subscales and NP burnout (N = 396)

| Modela | Practice environment subscale | Risk Ratio* | P > |z| | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Professional Visibility | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.66 |

| 2 | Independent Practice and Support | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.65 |

| 3 | NP-Physician Relations | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.71 |

| 4 | NP-Administration Relations | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.56 |

Note. NP = Nurse Practitioner;

Because we did not have NP responses recorded over various time points, we created a constant time variable. When there is a constant time variable in a multi-level cox regression model, the hazard ratio is the same as the risk ratio. Thus, we reported the risk ratio in this table; Four independent multi-level models were run, one for each practice environment subscale.

In each model, we controlled for age, sex, race, education, marital status, workload, years of experience as an NP, average hours worked per week, practice size, hours of operation (nights and weekends), type of primary care practice, survey type, and state.

Discussion

In this study, we examine the association between the primary care practice environment and burnout among NPs in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. We found that the prevalence of primary care NP burnout is 25.3% which is slightly higher than the combined burnout prevalence of 22.6% among primary care NPs and physician assistants, but comparable to the burnout prevalence rate of 25.1% among primary care physicians.9 Burnout among primary care NPs is concerning as it may affect the care that is delivered to patients. However, across all subscales, when NPs practice in favorable environments, the risk of them reporting burnout significantly decreases anywhere from 51% to 58%.

In particular, higher NP-PR, IPS, PV, and NP-AR subscale scores are associated with 51%, 56%, 51%, and 58% lower risk of NP burnout, respectively. These findings suggest that NP burnout decreases when NPs practice in environments that promote optimal relations with physicians and administrators, administrators have an understanding of NP role, skills, and competencies, and NPs are supported and provided resources needed to perform their jobs. Moreover, our findings specifically among primary care NPs are consistent with a recent study which found that nurses working in environments with strong collaboration, greater communication, effective decision making, and supportive administrators reported lower burnout.43 Thus, our study and existing studies7,43 highlight the important role of the practice environment in influencing burnout.

However, of the four practice environment subscales, NPs reported that their relations with practice administrators was the lowest. This finding is consistent with a prior qualitative study reporting that most NPs felt that administration was not supportive nor understanding of the contributions that NPs make to patient care, and in some cases, NPs were not represented within the administration.23 Although our study did not explore why NP-AR was suboptimal, it is important to investigate the relations between NPs and practice administrators since having favorable relationships with management may be important for ultimately reducing burnout.

Implications:

The results of this study provide implications for clinical practice. Since NPs are increasingly delivering patient care in primary care practices and play a vital role in the health care system, it is crucial to reduce NP burnout. With strong links already reported between provider burnout and adverse patient and organizational outcomes,4 it is essential that clinicians and administrators in primary care practices make reducing NP burnout an organizational priority. One way for clinicians and practice administrators to reduce NP burnout is by fostering the development of a healthy primary care practice environment. For example, in a qualitative study involving primary care physicians, NPs, and physician assistants from Massachusetts, researchers found that potential solutions to reducing burnout includes creating a healthy environment where a PCP’s voice is heard and promoted, open communication and collegial relations exist between leadership and other specialists, opportunities for visibility and professional growth exist, and a sense of community where PCPs can get to know their colleagues is embraced within the practice.44 Based on the results from our study, it is possible that creating a healthy practice environment may hold much potential for alleviating NP burnout.

In addition to practice implications, we also have implications for future research. Since NPs reported that their relations with administrators was least favorable when compared with the other three practice environment subscales, future research should investigate what interventions are successful in improving relations between NPs and administrators. It may be the case that limited autonomy for NPs negatively affects the relationship between NPs and administrators which may contribute to NP burnout. However, further research is needed to investigate whether primary care NP autonomy has any association with NP burnout. Additionally, only four NPs reported practicing in a nurse-managed clinic. Future studies should explore whether the practice environment for NPs differ when NPs practice in a NP-owned clinic compared to a physician owned clinic which most NPs in our study practiced. More research is needed to examine how the relations between primary care NPs and practice administrators are related to patient (e.g., quality of care, patient satisfaction) and organizational outcomes (e.g., turnover). Also, New Jersey and Pennsylvania are both states with reduced NP scope practice regulations and it may be possible that such policy level regulations influence primary care NP burnout, however more research is needed to confirm. Lastly, future research should be conducted with all PCPs (i.e., physicians, NPs, and physician assistants) which will allow researchers to better understand how burnout impacts all PCPs and the quality of care delivered to patients in primary care settings across the U.S.

Limitations

There are limitations in this study. The generalizability of study findings is limited because our sample stemmed from two states: New Jersey and Pennsylvania. In addition, we obtained data from primary care NPs, therefore our results might not be generalizable to all NPs. Moreover, it may be possible that the NPs in our study are more likely to be burned out since the sample was focused on NPs caring for older adults with chronic conditions, which may require greater care management and higher demand for NP services compared to NPs caring for healthier patients without as many co-morbidities. Since this study relied on self-report data, bias may be an issue. Despite best attempts to encourage NPs to complete the survey, the low response rate may suggest that the NPs in our study are unlike NPs nationally. However, we found that NPs in our study were relatively alike in race (89.4% White vs. 87% White nationally) and age (49.5 years vs. 49 years nationally) to NPs from the National Nurse Practitioner Sample Survey.45 Furthermore, we cannot conclusively say poor practice environments cause NP burnout since we had cross-sectional survey data and such data limits causal inference. Additionally, primary care clinician burnout rates are high among those working in a federally qualified health center,46 however, in our study, we did not ask NPs if they were working in a federally qualified health center. Similarly, participation in post-graduate NP residency programs, which was not explored in this study, is known to influence NP job satisfaction47,48 which may also influence NP burnout. As a result, there could be such other factors influencing NP burnout and that should be further investigated. Despite these limitations, our study contributes to the growing literature on provider burnout by identifying the current percentage of primary care NP burnout across two states and a key variable, the practice environment, that may contribute to their burnout.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the association between the primary care practice environment and NP burnout. This study provides valuable evidence and supports existing literature by showing that favorable NP practice environments have the potential for reducing primary care NP burnout. Additional research examining the association between NP practice environments with outcomes such as NP intention to leave the practice and quality of patient care are recommended.

25.3% of primary care NPs are burnt-out.

Favorable environments are associated with 51%−58% lower risk of NP burnout.

Organizational changes to the practice environment may reduce NP burnout.

Acknowledgements:

We thank all the nurse practitioners who completed the survey.

Funding: This study was supported by grant number R36HS027290 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, as well as from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Jonas Center for Nursing and Veterans Healthcare, and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01MD011514). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Jonas Center for Nursing and Veterans Healthcare, nor the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimers/Previous Presentation: This study was accepted as a poster presentation at Academy Health’s 2020 Annual Research Meeting.

Contributor Information

Cilgy M. Abraham, Columbia University School of Nursing, 560 West 168th Street-Mail Code 6, New York, NY 10032.

Katherine Zheng, Columbia University School of Nursing, 560 West 168th Street-Mail Code 6, New York, NY, 10032.

Allison A. Norful, Columbia University School of Nursing, 630 West 168th Street-Mail Code 6, New York, NY 10032.

Affan Ghaffari, Columbia University School of Nursing, 516 W. 168th Street, 2nd Floor; New York, NY 10032.

Jianfang Liu, Columbia University School of Nursing, 560 W. 168th Street, New York, NY 10032.

Lusine Poghosyan, 630 W. 168th Street, mail code 6; New York, NY 10032.

References

- 1.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The Measurement of Experienced Burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Johnson PO, et al. A cross-sectional study exploring the relationship between burnout, absenteeism, and job performance among American nurses. BMC Nurs. 2019;18:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourdeanu L, Zhou Q, DeSamper M, Pericak KA, Pericak A. Burnout, workplace factors, and intent to leave among hematology/oncology nurse practitioners. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2020; 11(2): 141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jha AK, Iliff AR, Chaoui AA, et al. A crisis in health care: A call to action on physician burnout. 2019. http://www.massmed.org/News-and-Publications/MMS-News-Releases/Physician-Burnout-Report-2018/. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- 6.McHugh MD, Kutney-Lee A, Cimiotti JP, et al. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(2):202–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lake ET, Sanders J, Duan R, et al. A Meta-Analysis of the Associations Between the Nurse Work Environment in Hospitals and 4 Sets of Outcomes. Med Care. 2019;57(5):353–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petterson S, McNellis R, Klink K, et al. The State of Primary Care in the United States: A Chartbook of Facts and Statistics. 2018. https://www.graham-center.org/content/dam/rgc/documents/publications-reports/reports/PrimaryCareChartbook.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 9.Edwards ST, Marino M, Balasubramanian BA, et al. Burnout Among Physicians, Advanced Practice Clinicians and Staff in Smaller Primary Care Practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(12):2138–2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abraham CM, Zheng K, Poghosyan L. Predictors and outcomes of burnout among primary care providers in the United States: A systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77(5):387–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabatin J, Williams E, Manwell LB, et al. Predictors and Outcomes of Burnout in Primary Care Physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):41–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e100–e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helfrich CD, Dolan ED, Simonetti J, et al. Elements of team-based care in a patient-centered medical home are associated with lower burnout among VA primary care employees. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S659–S666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zubatsky M, Pettinelli D, Salas J, Davis D. Associations between integrated care practice and burnout factors of primary care physicians. Fam Med. 2018;50(10):770–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AANP. NP Fact Sheet. 2020. https://www.aanp.org/about/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- 16.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. National and regional projections of supply and demand for primary care practitioners: 2013–2025. 2016. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/health-workforce-analysis/research/projections/primary-care-national-projections2013-2025.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2019.

- 17.AANP. What’s a Nurse Practitioner (NP)?. 2020. https://www.aanp.org/about/all-about-nps/whats-a-nurse-practitioner. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 18.Barnes H, Richards MR, McHugh MD, et al. Rural and Nonrural Primary Care Physician Practices Increasingly Rely on Nurse Practitioners. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(6):908–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buerhaus PI, DesRoches CM, Dittus R, et al. Practice characteristics of primary care nurse practitioners and physicians. Nurs Outlook. 2015;63(2):144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan KS, Gaskin DJ, McCleary RR, et al. Availability of Health Care Provider Offices and Facilities in Minority and Integrated Communities in the U.S. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2019;30(3):986–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carthon JMB, Brom H, Poghosyan L, et al. Supportive Clinical Practice Environments Associated With Patient-Centered Care. J Nurse Pract. 2020;16(4):294–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poghosyan L, Aiken LH. Maximizing nurse practitioners’ contributions to primary care through organizational changes. J Ambul Care Manage. 2015;38(2):109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poghosyan L, Nannini A, Stone PW, et al. Nurse practitioner organizational climate in primary care settings: implications for professional practice. J Prof Nurs. 2013;29(6):338–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brigham T, Barden C, Dopp AL, et al. A journey to construct an all-encompassing conceptual model of factors affecting clinician well-being and resilience. NAM Perspectives. 2018; 1–8. https://nam.edu/journey-construct-encompassing-conceptual-model-factors-affecting-clinician-well-resilience/. Accessed October 17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poghosyan L, Ghaffari A, Liu J, et al. Primary care nurse practitioners’ roles and work environment in six states with variable scope of practice regulations. Unpublished Manuscript. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.DesRoches CM, Barrett KA, Harvey BE, et al. The Results Are Only as Good as the Sample: Assessing Three National Physician Sampling Frames. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:S595–S601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. News and World Reports. Health care access rankings. 2019. https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/rankings/health-care/healthcare-access. Accessed March 13, 2019.

- 29.U.S. News and World Reports. Health care quality rankings. 2019. https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/rankings/health-care/healthcare-quality. Accessed March 13, 2019.

- 30.Poghosyan L, Nannini A, Finkelstein SR, et al. Development and psychometric testing of the Nurse Practitioner Primary Care Organizational Climate Questionnaire. Nurs Res. 2013;62(5):325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poghosyan L, Shang J, Liu J, et al. Nurse practitioners as primary care providers: creating favorable practice environments in New York State and Massachusetts. Health Care Manage Rev. 2015;40(1):46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rowand LC. Primary care nurse practitioners and organizational culture. Walden University Scholar Works. 2017; https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/dd9e/fcd56293f623f709d1b725b14a38c3b16854.pdf?_ga=2. 190946669.695970253.1592662801–2076557570.1592662801. Accessed June 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haupt EF. (2016). Predictors for Florida nurse practitioners’ characterization of organizational climate. Walden University Scholar Works. 2016; https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d015/4722289835565fe78cdc0637bc74d53b1f51.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):582–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. 2017; Armonk, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akinwande MO, Dikko HG, Samson A. Variance inflation factor: as a condition for the inclusion of suppressor variables in regression analysis. Open J Stat. 2015;5(7):754. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murray JS. Multiple imputation: A review of practical and theoretical findings. Statistical Science. 2018;33(2): 142–159. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCleary L. Using multiple imputation for analysis of incomplete data in clinical research. Nurs Res. 2002;51(5):339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bodner TE. What improves with increased missing data imputations? Struct Equ Modeling. 2008;15(4):651–675. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stata Corp. STATA statistical software: Release 14. 2015; College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diaz-Quijano FA. A simple method for estimating relative risk using logistic regression. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee J, Chia KS: Estimation of prevalence rate ratios for cross sectional data: an example in occupational epidemiology. Br J Ind Med.1993;50:861–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim LY, Rose DE, Ganz DA, et al. Elements of the healthy work environment associated with lower primary care nurse burnout. Nurs Outlook. 2020;68(1):14–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agarwal SD, Pabo E, Rozenblum R, Sherritt KM. Professional dissonance and burnout in primary care: A qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(3):395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.AANP. The state of the nurse practitioner profession: results from the national nurse practitioner sample survey. 2019. https://www.aanp.org/news-feed/nurse-practitioner-role-continues-to-grow-to-meet-primary-care-provider-shortages-and-patient-demands. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 46.Friedberg MW, Reid RO, Timbie JW, et al. Federally qualified health center clinicians and staff increasingly dissatisfied with workplace conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1469–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Painter J, Sebach AM, Maxwell L. Nurse practitioner transition to practice: development of a residency program. J Nurse Pract. 2019; 688–691. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bush CT, Lowery B. Postgraduate nurse practitioner education: impact on job satisfaction. J Nurse Pract. 2016; 12(4): 226–234. [Google Scholar]