Abstract

Antibiotic resistance has emerged as a threat to global health, food security, and development today. Antibiotic resistance can occur naturally but mainly due to misuse or overuse of antibiotics, which results in recalcitrant infections and Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) among bacterial pathogens.

These mainly include the MDR strains (multi-drug resistant) of ESKAPE (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species). These bacterial pathogens have the potential to “escape” antibiotics and other traditional therapies. These bacterial pathogens are responsible for the major cases of Hospital-Acquired Infections (HAI) globally. ESKAPE Pathogens have been placed in the list of 12 bacteria by World Health Organisation (WHO), against which development of new antibiotics is vital. It not only results in prolonged hospital stays but also higher medical costs and higher mortality. Therefore, new antimicrobials need to be developed to battle the rapidly evolving pathogens. Plants are known to synthesize an array of secondary metabolites referred as phytochemicals that have disease prevention properties. Potential efficacy and minimum to no side effects are the key advantages of plant-derived products, making them suitable choices for medical treatments. Hence, this review attempts to highlight and discuss the application of plant-derived compounds and extracts against ESKAPE Pathogens.

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, ESKAPE, Traditional medicine, Hospital acquired infection, Phytochemicals

Antimicrobial resistance; ESKAPE; Traditional medicine; Hospital acquired infection; Phytochemicals

1. Introduction

Many new antibiotics have been produced in the last four decades by pharmacological industries, and resistance by microorganisms to these drugs have been accelerated due to impetuous use of antibiotics. A report submitted to the United Nations in 2019, expects that infections caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria would cause 10 million deaths per annum and an economic crisis just like the 2008–2009 global financial collapse by 2050 [1]. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) can be conferred in bacteria via genetic mutation and Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) through chromosomes, plasmids, transposons and other mobile genetic elements [2]. AMR is a natural prevalence that is connected to a rise in "mortality, morbidity and economic burden" of nations worldwide [3]. Till date, there have been no evidences for effective antimicrobial compounds against the AMR bacteria caused infections [4, 5]. Thus, there is an immediate need for novel treatment methods targeting the issues caused by AMR.

Global priority pathogen list (PPL) was released by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2016 to guide the researcher in discovery, and development of new antibiotics [6]. In this sequence the five-year NAP (National Action Plan) for the control of AMR (2017–2021) that was developed by the Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in April 2017, was presented at the 70th World Health Assembly (WHA) held at Geneva in May 2017. It geared towards increasing awareness, surveillance and investment in research to combat the spread of AMR. However, there are many hurdles to overcome such as lack of funding, strict implementation and ethical commercial practices [7].

The prime class of opportunistic pathogens that are a universal threat to humankind are entitled as ‘ESKAPE’ (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp.) as they are known to “escape” antibiotics and other traditional treatments [8]. This imminent health threat has activated the development of novel antimicrobial therapies, where better care of the patient and improved governance happens to be the requirement of the hour.

The European Center for Disease Control (ECDC) and the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in USA gave the subsequent standardized definitions for multidrug resistant (MDR), extensively drug resistant (XDR), and pan drug resistant (PDR) bacteria: multidrug resistance (MDR) is defined as acquired non-susceptibility to a minimum of one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories. Extensively drug resistance (XDR) is defined as non-susceptibility to a minimum of one agent altogether but two or fewer antimicrobial categories (i.e., bacterial isolates remain vulnerable to just one or two antimicrobial categories). The non-susceptibility to all agents in all antimicrobial categories is called Pan Drug Resistance (PDR) [9].

For a long period of time people of India have been using many plant species as traditional medicines for a variety of ailments, including treatment of infectious diseases [10]. Discovery of novel drugs can be accomplished with the use of plants extracts, which is a reservoir of broad-spectrum secondary metabolites [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]. Plants have proven themselves to be effective in preventing and treating the toxicity induced by other toxins or drugs. The efficacy of plant extracts and their derivatives in terms of their antimicrobial activities have paved the way for the exploration of new and effective treatments against MDR-ESKAPE. This review targets the use of such diverse traditional medicinal plants, which are capable of being used effectively as anti-ESKAPE drugs.

2. ESKAPE: a threat to public health

Antimicrobial resistance represents a global threat to human health. AMR is found in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains of bacteria. India's AMR rates are alarmingly high when compared to other nations. For instance, the percentage of clinical isolates of MRSA (Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus) nearly doubled over a period of just 6 years (2008–2014) from 29% to 47%. Other nations reported a decline in the percentage of MRSA as a result of extensive antibiotic stewardship and awareness practices [24]. The Carbapenem resistant A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, E. faecium, Methicillin resistant, vancomycin intermediate/resistant S. aureus and other members of Enterobacteriaceae are [25] known as “superbugs” or ESKAPE. The above mentioned pathogens are responsible for lethal infections amongst critically ill and immunocompromised individuals as a result of lack of treatment [26]. Thus the consequences of ESKAPE could be devastating.

2.1. Enterococcus faecium (E. faecium)

E. faecium is a Gram-positive spherical (cocci) bacterium that occurs in pairs or chains, commonly involved in nosocomial infections amongst immunocompromised patients. β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin and other last resort antibiotics have no effect on E. faecium. [27]. Resistance to Vancomycin, in particular, has led to a significant increase in Vancomycin resistant Enterococci (VRE) strains [27]. A gene of VRE encodes for a putative Enterococcal Surface Protein that aids in the formation of thicker biofilms [28]. Infections caused by it include urinary tract infections (UTI), bacteremia, intra-abdominal infections, and endocarditis. Enterococci are now the third most common nosocomial pathogen that caused 14% of hospital-acquired infections in the United States between 2011 and 2014, compared to 11% in 2007. Aside from nosocomial infections, enterococci are responsible for 5–20% of community-acquired endocarditis [29].

2.2. Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus)

S. aureus is a Gram-positive spherical (coccus) bacteria that's commonly found in human skin microbiota and is typically harmful only in immunocompromised individuals. Being a part of normal microflora of skin, it usually causes infections when it invades the regions that it typically does not inhabit, such as bruises and wounds. S. aureus is capable of causing infections on medical implants and forming biofilms that poses a challenge in antibiotics mediated treatment. Moreover, approximately 25% of S. aureus strains secrete the TSST-1 exotoxin which is responsible for causing toxic shock syndrome. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), a special strain of S. aureus, is known to have evolved resistance against β-lactam antibiotics [27]. They confer resistance to β-lactam antibiotics by the expression of mecA that encodes a low penicillin binding affinity protein (PBP 2a) [30]. They are associated with an increasing number of health care related infections, particularly seen in infective endocarditis and prosthetic device infections. Also, strains with particular virulence factors and resistance to β-lactam antibiotics are some of the major causes of community-associated skin and soft tissue infections [31]. Certain S. aureus strains have been identified as resistant to Vancomycin-intermediate owing to the overuse of the drug for the treatment of S. aureus [32].

2.3. Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae)

K. pneumoniae is a Gram-negative rod-shaped (bacillus). According to Shiri et al., about one-third of all Gram negative infections such as UTI, Septicemia, Surgical Wound Infections, Cystitis, Pneumonia and endocarditis can be attributed to this organism. It is also known to cause necrotizing pneumonia, pyogenic liver abscesses and endogenous endophthalmitis. K. pneumoniae infections account for its high mortality rates, extended hospitalization, coupled with expensive treatments. A significant rise in the occurrence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extremely drug-resistant (XDR) pathogens of the Enterobacteriaceae group is posing a global economic threat nowadays. Certain strains have been classified as carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP), because of the development of β-lactamases, which makes them resistant to commonly used antibiotics, such as carbapenems. There are only a few antibiotics in development which will treat infection [27, 33, 34].

2.4. Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii)

A. baumannii is a Gram-negative, strictly aerobic, non-fermenting, non-fastidious, catalase-positive, oxidase-negative coccobacillus or pleomorphic bacterium that is responsible for almost 2 per cent of all nosocomial infections in the US and Europe and twice as high in Asia and the Middle East. 45% of all isolates of this deadly, opportunistic pathogen around the world have been reported as Multidrug Resistant (MDR). The most usual types of infections caused by this bacterium are Central line- associated bloodstream infections and ventilator-associated pneumonia. The ability to resist desiccation, form biofilms and presence of fundamental virulence factors, such as surface adhesins, glycoconjugates and secretion systems help A. baumannii to thrive in this environment [35].

2.5. Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa)

P. aeruginosa is a Gram-negative, gamma-proteobacterium possessing a lowly permeable outer membrane and multiple transport systems that provide it innate resistance to many antibiotics. It also employs a variety of mechanisms such as alterations in porin channels, efflux pumps, target modifications, and β-lactamases that allow it to develop resistance to antimicrobial agents [36]. Cystic fibrosis (CF) patients are at a particularly high risk of acquiring this infection because of its ability to form biofilms and persister cells in the lungs [37]. Point mutations on DNA gyrase/Topoisomerase IV provide immense resistance against Fluoroquinolones to P. aeruginosa [38].

2.6. Enterobacter spp.

Enterobacter spp. are Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria that are members of the Enterobacteriaceae family. Immunocompromised patients such as those on mechanical ventilation or implanted with IMD are most susceptible to urinary or respiratory tract infections by this pathogen. E. cloacae is the most commonly found species in patients causing 4%–5% of all nosocomial bacteraemia, pneumonia and urinary tract infections [39]. They show broad resistance to antimicrobials by plasmid encoded ESBLs, carbapenems [4].

3. Plant derived compounds and extracts against ESKAPE

Conventional medicinal practices utilize plants against various infections for over thousands of years now [40, 41, 42, 43]. 80% of the population in the developing nations are dependent upon the easily accessible traditional medications to fulfil their primary medical needs, [44, 45]. Indeed, plants are known to synthesize a wide array of compounds known as secondary metabolites or phytochemicals such as quinones, tannins, terpenoids, alkaloids, flavonoids, and polyphenols which have disease prevention properties and aid them in their self-defense and communication with other organisms in their environment [46]. Plant extracts as medicines are inevitable substitutions for antibiotics prescribed by physicians [47] Plant derived compounds and extracts are commonly used in self-medication due to its easy availability, competence and nil side effects [47].

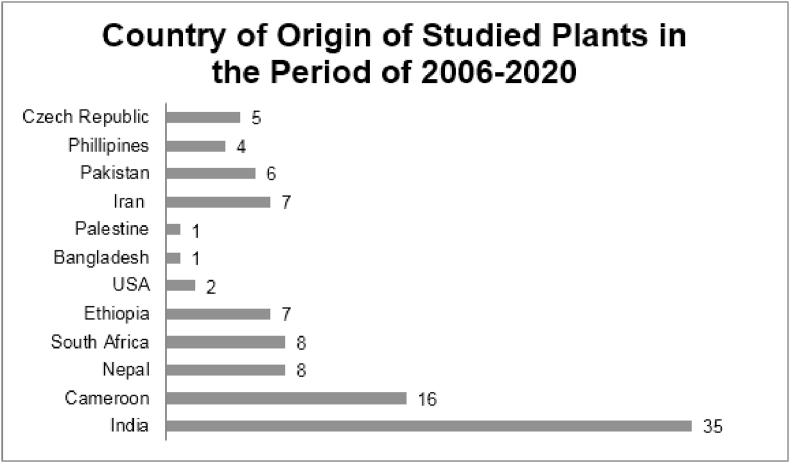

Table 1 shows a total of 100 plants that were reported to show significant antimicrobial activity against ESKAPE pathogens during the period of 2006–2020. These plants were reported from 12 countries from Asia, Africa, Europe, North America and South America. India reported the highest number (35) of plants (Chart 1).

Table 1.

Plant-derived compounds and plant extracts reported during 2006–2020 against ESKAPE.

| S. No. | Scientific Name | Common Names | Parts used | Traditional uses | Extract prepared in | Anti -microbial activity against | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cinnamomum glaucescens | Sugandhakokila | Leaves | Skin and throat infection | Acetone | MRSA | Panda et al., 2020 [48] | ||||

| 2 | Smilax zeylanica | Kumarika | Leaves | Ulcers treatment | Acetone | MRSA | Panda et al., 2020 [48] | ||||

| 3 | Syzygium praecox | N/A | Leaves | Skin infection | Acetone | MRSA | Panda et al., 2020 [48] | ||||

| 4 | Trema orientalis | Charcoal tree | Leaves | Sore throat, boils, wound infections | Acetone | MDR-S | Panda et al., 2020 [48] | ||||

| 5 | Bischofia javanica | Java cedar | Leaves | Skin diseases | Acetone | MDR-S | Panda et al., 2020 [48] | ||||

| 6 | Elaeocarpus serratus | Ceylon olive | Flower | Acts as a diuretic and cardiovascular stimulant | Water | MDR-S | Panda et al., 2020 [48] | ||||

| 7 | Acacia pennata | Climbing acacia | Leaves | Effective against dysentery, diarrhoea and lowers body cholesterol | Ethanol | MRSA | Panda et al., 2020 [48] | ||||

| 8 | Holigarna caustica | Long-leaf varnish tree | Fruit | Skin diseases | Ethanol | MRSA | Panda et al., 2020 [48] | ||||

| 9 | Murraya paniculata | Orange jessamine | Leaves | Cure to cardiovascular disorders | Ethanol | MRSA | Panda et al., 2020 [48] | ||||

| 10 | Pterygota alata | Buddha coconut | Bark | Skin diseases | Ethanol | MDR-S | Panda et al., 2020 [48] |

||||

| 11 | Kalanchoe fedtschenkoi | Lavender scallops | Woody stems | Used as an analgesic (Cumberbatch, 2011) [49] | Ethanol | S,A,P | Richwagen et al., 2019 [50] |

||||

| 12 | Bridelia micrantha | Coastal golden leaf | Stem bark | Used in Cameroon to treat amoebic dysentery, cough diarrhoea, gastric ulcer, eye diseases, infertility and tapeworms. Has antibacterial, hepatoprotective, antioxidant, antitumor and antiviral activities | Methanol | S, K, P, MRSA, Ea | Ngane et al., 2019 [51] | ||||

| 13 | Prunus cerasifera | Cherry plum | Fruit | Astringent, antioxidant, sudorific, antipyretic, axative and diuretic properties | Methanol | K,S,P | Pallah et al., 2019 [52] | ||||

| 14 | Ribes nidigrolaria | Jostaberry | Fruit | Anti-aging, cataracts, cardiovascular disease, immunity. | Methanol | P,S | Pallah et al., 2019 [52] | ||||

| 15 | Prunus avium | Sweet Cherry | Fruit | Cancer, osteoarthritis and cardiovascular disease | Methanol | K,S,P | Pallah et al., 2019 [52] | ||||

| 16 | Prunus subg. Prunus | Plum | Fruit | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and memory-boosting properties | Methanol | K,S,P | Pallah, et al., 2019 [52] | ||||

| 17 | Ribes rubrum | Red Currant | Fruit | To treat scurvy, relieve constipation, digestive and urination issues, laxative | Methanol | K,S,P | Pallah et al., 2019 [52] | ||||

| 18 | Adiantum capillus-veneris | Maiden hair fern | Whole plant | Urinary tract infections (UTIs); also used as an astringent, demulcent, antitussive and diuretic (Ishaq et al., 2014) [53] |

Ethanol | Ef,S | Khan et al., 2018 [54] | ||||

| 19 | Artemisia absinthium | Worm wood | Aerial parts | Pruritus and inflammatory and infectious skin disorders, (Khan and Khatoon, 2008) [55] Drugs against malaria and typhoid (Hayat et al., 2009) [56] |

Ethanol | Ef,S | Khan et al., 2018 [54] | ||||

| 20 | Martynia annua | Bichoo | Fruit | Wound healing, skin conditions and sore throats (Santram and Singhai, 2011; Dhingra et al., 2013) [57,58] |

Ethanol | K,A,Ef,S | Khan et al., 2018 [54] | ||||

| 21 | Swertia chirata | Chirayita | Whole plant | Hepatitis, inflammation and digestive diseases. Other indications include chronic fever, malaria, skin disease and bronchial infections (Kumar and Van Staden, 2016) [59]. | Ethanol | S | Khan et al., 2018 [54] | ||||

| 22 | Zanthoxylum armatum | Timber | Fruit | Cancer and digestive ailments such as cholera and dysentery, dental infections and oral sores (Ahmad et al., 2014; Alam and Saqib, 2017) [60, 61]. |

Ethanol | Ef,S | Khan et al., 2018 [54] | ||||

| 23 | Berberis lycium Royle | Indian Lycium | Root | Bark infusions are traditionally used for oral infections, toothaches and earaches (Abbasi et al., 2010) [62]. Traditionally used to treat diarrhea, cholera and piles (Malik et al., 2017) [63]. | Ethanolic and Aqueous | Ef | Khan et al., 2018 [54] | ||||

| 24 | Anacardium occidentale | Cashew | leaves | Venereal diseases, stomach issues, skin diseases, stomatitis, bronchitis, psoriasis, toothaches, and gum problems | Ethanol | K, P, S | Shobha et al., 2018 [64] | ||||

| 25 | Piper longum | Pipli | Root | Antioxidant potential and anti-inflammatory properties | Aqueous | Ef, A | Chandrasekharan et al., 2018 [65] | ||||

| 26 | Cymbopogon citratus | Lemon grass | Leaves | Treatment against hypertension, epilepsy, gastrointestinal, central nervous system disorders | Hexane | P, Ec | Chandrasekharan et al., 2018 [65] | ||||

| 27 | Aloe vera | Medicinal aloe | Leaves | Help with skin injuries caused by burning, irritations, cuts, actively repairs damaged skin | Aqueous | S | Chandrasekharan et al., 2018 [65] | ||||

| 28 | Cynodon dactylon | Bermuda grass | Leaves | Laxative, coolant, brain and heart tonic | Ethanol | K | Chandrasekharan et al., 2018 [65] | ||||

| 29 | Theobroma cacao | Cocoa | Seeds Leaves |

Stimulates nervous system, low blood pressure and softens damaged skin. Effective against anemia, diarrhea and bruises | Methanol |

K Ea |

Nayim et al., 2018 [66] | ||||

| 30 | Ipomoea batatas | Sweet potato | Leaves | Treatment of diabetes, hypertension, and stomach related issues, arthritis, rheumatoid diseases, meningitis, kidney ailments, and inflammations. | Methanol | Ea | Nayim et al., 2018 [66] | ||||

| 31 | Azadirachta indica | Neem tree | Bark | Used to treat teeth-related issues and disorders of the GI tract, malaria fevers, skin diseases, and as insect repellent | Methanol | Ea, K | Nayim et al., 2018 [66] | ||||

| 32 | Citrus grandis | Pomelo | Leaves | To treat epilepsy, chorea, Convulsive cough and also in the treatment of hemorrhage disease. | Methanol | K | Nayim et al., 2018 [66] | ||||

| 33 | Cucurbita maxima | Winter squash | Beans | Treat intestinal infections and kidney problems and to fight tapeworms | Methanol | K | Nayim et al., 2018 [66] | ||||

| 34 | Dacryodes edulis | Bush butter tree | Leaves seeds | Gargle and mouth wash to treat tonsillitis | Methanol |

Ea, Ec Ea, P |

Nayim et al., 2018 [66] | ||||

| 35 | Hibiscus esculentus | Okra | Leaves | Used in the treatment of nose and throat related infections, urine associated issues and gonorrhoea | Methanol | Ea | Nayim et al., 2018 [66] | ||||

| 36 | Phaseolus vulgaris | Common bean | Leaves | Consumed orally for weight loss and obesity. Taken for diabetes as well | Methanol | Ea, P | Nayim et al., 2018 [66] | ||||

| 37 | Lantana camara | Lantana | Leaves | Antispasmodic, anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, anti-malarial,anti-ulcerogenic | Dichloromethane, methanol, petroleum ether, chloroform, ethyl acetate, acetone, ethanol and water |

MRSA, MDR-A, VRE, P | Subramani et al., 2017 [67] | ||||

| 38 | Butea monosperma | Palash | Leaves | Stimulation of diuresis and menstrual flow. | Petroleum ether, acetone, methanol, ethanol and water | MRSA, VRS | Subramani et al., 2017 [67] | ||||

| 39 | Terminalia chebula | Myrobalan | Dried seedless ripe fruits | Treats High cholesterol and digestive disorders, dysentery | Cold and hot aqueous and ethanol | MRSA | Subramani et al., 2017 [67] | ||||

| 40 | Anthocephalus cadamba and Pterocarpus santalinus | Burflower tree and red sandalwood | Leaves and bark | Treatment of fever, uterine complaints, skin diseases, inflammation. Antipyretic, dysentery, antihyperglycaemic | Ethanol and water | MDR-A species, P | Subramani et al., 2017 [67] | ||||

| 41 | Andrographis paniculata | Green chireta | - | Anti-cancer, anti-diabetic, helps overcome high blood pressure, ulcer, lung related issues, skin diseases | Chloroform and chloroform + HCl | MRSA | Subramani et al., 2017 [67] | ||||

| 42 | Callistemon rigidus | Stiff bottlebrush | Leaves | Treatment of diarrhea, dysentery, rheumatism, anticough and antibronchitis | Methanol | MRSA | Subramani et al., 2017 [67] | ||||

| 43 | Myrtus communis | Myrtle | Leaves | Diabetes, ulcers, hypertension, dysentery, rheumatism, cancer, inflammations and diarrhea | Hydro-alcoholic | P, S | Masoumian and Zandi, 2017 [68] | ||||

| 44 | Cinnamomun zeylanicum | Cinnamon | Bark | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic properties | Water | P, S | Masoumian and Zandi, 2017 [68] | ||||

| 45 | Mentha sp. | Mint | Leaves | Effective against cold, irritable bowel syndrome, indigestion | Aqueous hydro-alcoholic |

P S |

Masoumian and Zandi, 2017 [68] | ||||

| 46 | Lawsonia inermis | Henna | Leaves | Heals wounds and burns, used for skin infections, hair health | Aqueous | P, S | Masoumian and Zandi, 2017 [68] | ||||

| 47 | Aloe vera | Medicinal aloe | Leaves | Burns, acne, oral and digestive problems | Aqueous | P, S | Masoumian and Zandi, 2017 [68] | ||||

| 48 | Zingiber officinale | Ginger | Roots | Nausea, vomiting, anti-cancer | Hydro-alcoholic | P, S | Masoumian and Zandi, 2017 [68] | ||||

| 49 | Bulbine frutescens | Snake flower | Leaves and bulbs | Skin and wound conditions. (Van Wyk et al., 2009; Diederichs et al., 2009) [69, 70] | Chloroform and methanol | S,P | Ghuman et al., 2016 [71] |

||||

| 50 | Aloe ferox | Bitter Aloe | Leaves | Skin conditions (Van Wyk et al., 2009; Diederichs et al., 2009) [69, 70] | Chloroform | S,P,K | Ghuman et al., 2016 [71] | ||||

| 51 | Mentha longifolia | Horse mint | Aerial parts | Throat irritation, mouth and sore throat (Al-Bayati, 2009) [72] | Ethanol | VRE | Agarwal et al., 2016 [73] | ||||

| 52 | Phyllanthus emblica | Amla | Aerial parts | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti pyretic, analgesic, adaptogenic, hepatoprotective (Gulati et al., 1995; Baliga et al.,2012) [74, 75] | Ethanol | MRSA, VRE | Agarwal et al., 2016 [73] | ||||

| 53 | Aloe arborescens | Tree Aloe | Leaves | Skin, digestive and respiratory conditions (Hutchings et al., 1996; Crouch et al., 2006; Klos et al., 2009; Van Wyk et al., 2009) [69, 76, 77, 78] | Dichloromethane | S,P | Ghuman et al., 2016 [71] |

||||

| 54 | Hypericum aethiopicum | N/A | Leaves | Skin and gastrointestinal issues. (Rood, 1994; Bruneton, 1995; Hutchings et al., 1996; Van Wyk et al., 2009) [69, 76, 79, 80] | Dichloromethane, Chloroform, Methanol. | S,K | Ghuman et al., 2016 [71] | ||||

| 55 | Aframomum corrorima | Ethiopian Cardamom | Fruit | Substitute medication for the regional community and scientific research in search for substitute drugs to overcome challenges associated with the rising antimicrobial resistance | _ | S | Bacha et al., 2016 [81] | ||||

| 56 | Camellia sinensis | Green Tea |

Leaves | Anticancer activity, Cardiovascular Diseases (Miura et al., 2000; Smith and Dou, 2001) [30, 82] | Ethanol | MRSA | Agarwal et al., 2016 [73] | ||||

| 57 | Mentha longifolia | Horse mint | Aerial parts | Throat irritation, mouth and sore throat (Al-Bayati, 2009) [72] | Ethanol | VRE | Agarwal et al., 2016 [73] | ||||

| 58 | Phyllanthus emblica | Amla | Aerial parts | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti pyretic, analgesic, adaptogenic, hepatoprotective (Gulati et al., 1995; Baliga et al., 2012) [74, 75] | Ethanol | MRSA, VRE | Agarwal et al., 2016 [73] | ||||

| 59 | Oxalis corniculata | Yellow sorrel | Leaves | Digestion, chronic dysentery, diarrhea, headaches, intoxication, fever, inflammations, jaundice, pain, scurvy, anti-helminthic, analgesic, astringent, diuretic | Methanol | K,S | Manandhar et al., 2015 [83] | ||||

| 60 | Cinnamomum tamala | Bay leaf | Leaves | Diabetes, Digestion, Cardiovascular Benefits, Cold and Infection, Pain, Anti-cancer, Menstrual Problems | Methanol | S | Manandhar et al., 2015 [83] | ||||

| 61 | Ageratina adenophora | Cotton weed | Leaves | Cuts, wounds, boils, antiseptic | Methanol | S | Manandhar et al., 2015 [83] | ||||

| 62 | Artemesia vulgaris | Mugwort | Aerial parts | Antiseptic, diarrhea, dysmenorrhea, asthma, antihelminthic, stomach ulcer, anorexia, heartburn, hyperacidity, spasm of digestive organs, epilepsy | Methanol | S | Manandhar et al., 2015 [83] | ||||

| 63 | Cynodon dactylon | Bermudagrass, Doob grass | Whole plant | Cuts, wounds, indigestion,genitourinary disorders (Rajbhandari., 2001; Manandhar, 2002; Singh et al., 2012) [84, 85, 86] | Ethanol, Chloroform |

MRSA, IRP, ESBL-K |

Quinn et al., 2015 [87] | ||||

| 64 | Curcuma longa | Turmeric | Rhizomes | Antiseptic, cuts, wounds, as anthelmintic, jaundice, liver disorders (Rajbhandari., 2001; Manandhar, 2002; Singh et al., 2012) [84, 85, 86] | Ethanol and Chloroform | MRSA, Ef | Quinn et al., 2015 [87] | ||||

| 65 | Ginkgo biloba | Ginkgo | Leaves | As antiaging, used to treat Alzheimer’s disease, as anticoldness, as antinumbness (Rajbhandari, 2001; Manandhar, 2002) [84, 85] | Ethanol and Chloroform | S,Ef | Quinn et al., 2015 [87] | ||||

| 66 | Rauwolfia serpentine | Serpentine (Sarpagandha) | Root | As antidysenteric, as antidote to snakebite, cuts, wounds, and boils (Rajbhandari., 2001; Manandhar, 2002; Singh et al., 2012) [84, 85, 86] | Ethanol and Chloroform |

MRSA,S, Ef, IRP, ESBL- K |

Quinn et al., 2015 [87] | ||||

| 67 | Croton macrostachyus Del. | Rushfoil | Leaves | Veterinary: diarrhea (dysentery), external parasites etc. (Adedapo et al., 2008) [88] | Methanol and Chloroform | S,P | Romha et al., 2015 [89] | ||||

| 68 | Calpurnia aurea | Wild laburnum | Leaves | Human: diarrhea, dysentery, and stomach disorder (Wagate et al., 2010) [90] | Methanol and Chloroform | S,P | Romha et al., 2015 [89] | ||||

| 69 | W. somnifera L. | winter cherry | Roots | Human: extended flow of menstruation/menometrorrhagia (bark & leaf), gallstone (root & leaf) (Alam et al., 2012) [91] | Methanol and Chloroform | P | Romha et al., 2015 [89] | ||||

| 70 | Nicotiana tabacum L. | Tobacco | Leaf | Used to treat infected wounds, hair treatment to prevent baldness, used in case of chills, snake bites | Methanol and chloroform | S, P | Romha et al., 2015 [89] | ||||

| 71 | Phyllanthus niruri | Sampa-sampalukan | Leaves, aerial parts | Problems of stomach, genitourinary system, liver, kidney and spleen, and to treat chronic fever (Kamruzzaman and Obydul Hoq, 2016) [92] | Ethanol | MRSA, VRE, S | Demetrio et al., 2015 [93] | ||||

| 72 | Psidium guajava | Bayabas | Leaves | Anti-diarrhoeal, to treat gastroenteritis, dysentery, stomach problems (Martha et al., 2008) [94] | Ethanol | MRSA, VRE, S | Demetrio et al., 2015 [93] | ||||

| 73 | Piper betle | Ikmo | Leaves | Mouth freshener, effective against parasitic worms, antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities (Fazal et al., 2014) [95] | Ethanol | MRSA, MβL A, MβL P, VRE, ESBL-KP, S, K,P | Demetrio et al., 2015 [93] | ||||

| 74 | Ehretia microphylla | Tsaang gubat | Leaves | Antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-allergic as well as anti-snake venom properties (Shukla et al., 2018) [96] | Ethanol | MRSA, MβL A, VRE, S, P | Demetrio et al., 2015 [93] | ||||

| 75 | Tabebuia impetiginosa | Tahuari | Whole plant | Treatment of rheumatism and, wounds, bronchitis and diarrhea. | Ethanol | P | Ulloa-Urizar et al., 2015 [97] | ||||

| 76 | Maytenus macrocarpa | Chuchuhuasi | Whole plant | Urine related issues, anti-cancerous, syphylis, gasterointestinal problems, diabetes | Ethanol | P | Ulloa-Urizar et al., 2015 [97] | ||||

| 77 | Eucalyptus camaldulensis | River red gum | - | Hot water extracts of dried leaves used as analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antipyretic remedies for the symptoms0 of respiratory infections, such as cold, flu, and sinus congestion. (Darwish and Aburjai, 2010) [98]. | Ethanol | P | Amenu, 2014 [99] | ||||

| 78 | Ficus sycomorus | Sycamore fig | Leaves | Ficus sycomorus have been suspected to possessanti-diarrhoeal activities and sedative and anticonvulsant properties of this plant have also been reported. (Cuaresma et al.,2008) [100] | Methanol and Aqueous | S | Amenu, 2014 [99] | ||||

| 79 | Entada abyssinica | Splinter bean | Leaves and roots | Coughs, fever, rheumatic, abdominal pains, and diarrhea, prevent miscarriage, gonorrhea, Bronchite, eyes inflammation, snake bite, sleeping sickness |

Methanol | S, K | Tchana et al., 2014 [101] | ||||

| 80 | Carica papaya | Papaya | Seeds | Typhoid fever, parasitic diseases, hepatic affections, dyspepsia, colic, gastric ulcer, toothache, analgesic, amebicide, antibacterial, febrifuge, hypotensive, laxative |

Ethanol and aqueous | K, P | Tchana et al., 2014 [101] | ||||

| 81 | Carapa procera | Carapa | Bark | Wound infections | Ethanol | P | Tchana et al., 2014 [101] | ||||

| 82 | Persea americana | Avocado | Stones | Diarrhea, dysentery, toothache, intestinal parasites, hypertension, cancer, menstrual problems, inflammation, wounds |

Methanol, ethyl acetate and chloroform | K, P | Tchana et al., 2014 [101] | ||||

| 83 | Adansonia digitata | African baobab | Pulps, Fruits, leaves, Pip, Bark | Analgesic, anti-diarrheal, smallpox, rubella, antipyretic, fever, dysenteria, anti-inflammatory, astringent (Tanko et al., 2008; Kaboré et al., 2011) [102,103] | Ethanol and Aqueous Extract | S,P | Djeussi et al., 2013 [104] | ||||

| 84 | Aframomum polyanthum | Matunguru | Fruits | - | Methanol | S | Djeussi et al., 2013 [104] | ||||

| 85 | Hibiscus sabdarifa | Roselle | Flowers | Diuretic, stomachic, laxative, aphrodisiac, antiseptic, astringent, cholagogue, sedative, hypertension and other cardiac diseases (Olaleye, 2007) [105] | Ethanol, Methanol,Aqueous | S,K,P | Djeussi et al., 2013 [104] |

||||

| 86 | K. pinnata | Cathedral bells | Leaves | Healing of Wounds caused by S and P, anti-microbial properties | 95% Ethanolic, 60% Methanolic and Aqueous | S,P | Pattewar et al., 2013 [106] | ||||

| 87 | Acacia karroo | Sweet thorn | Stem | Mouth ulcers, oral thrush, diarrhea, dysenteries, colic, colds, other Acacia pecies: asthma, bronchitis, cough, phithisis, fever, leprosy, chest and respiratory ailments (Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Johnson, 1999; Van Wyk et al., 2006) [107, 108, 109] | Methanol | ARKP | Nielsen et al., 2012 [110] | ||||

| 88 | Curtisia dentate | Assegaai tree | Stem bark | Stomach ailments, diarrhea, blood purifier, afrodisiac, tanning, chewing sticks (Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Van Wyk et al., 2006) [107, 109] | Methanol | MRSA | Nielsen et al., 2012 [110] | ||||

| 89 | Erythrophleum lasianthum | Sasswood | Stem and leaves | Headaches, fever, Erythrophleum species: heart problem, dermatitis, wounds, rheumatism, syphilis, gonorrhea, leprosy, tuberculosis, bronchitis, angina, ordeal and hunting poison (Palgrave et al., 1988; Neuwinger, 1996; Johnson, 1999) [108, 111, 112] | Methanol | MRSA | Nielsen et al., 2012 [110] | ||||

| 90 | Salvia africana-lutea | Golden sage | Aerial parts | Colds, flu, bronchitis, abdominal and uterine troubles, cough, chest troubles, other Salvia species: night sweat tuberculosis, respiratory and pulmonary ailments (Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Johnson, 1999; Van Wyk et al., 2006) [107, 108, 109] | Methanol | MRSA | Nielsen et al., 2012 [110] | ||||

| 91 | Toddalia asiatica | Orange climber | Leaves | Traditionally used to treat malaria and cough; indigestion and influenza and the leaves are used to treat lung diseases and rheumatism. | Ethyl acetate | K, Ea | Karunai Raj et al., 2012 [113] | ||||

| 92 | Kalanchoe pinnata | Patharkuchi | Stems and leaves | Diarrhea, dysentery and gastrointestinal disturbances. (Pal et al., 1991) [114] | Ethanol | S,P | Biswas et al., 2011 [115] | ||||

| 93 | Acacia nilotica | Gum Arabic Tree | Leaves | Antimicrobial, antihyperglycemic and antiplasmodial properties | Ethanol | K | Khan et al., 2009 [116] | ||||

| 94 | Cinnamum zeylanicum | Cinnamon | Barks | Antipyretic activity, antibacterial, antioxidant and antifungal properties | Ethanol | K | Khan et al., 2009 [116] | ||||

| 95 | Syzygium aromaticum | Clove | Bud | Antipyretic activity, antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory and anticarcinogenic effects | Ethanol | K | Khan et al., 2009 [116] | ||||

| 96 | Syzygium lineare | Malai naaval | Leaves | Diuretic, stomachic, tonic and astringent (Nadkarni, 1976; Rastogi and Mehrotra, 1990–1994; Narasimhan, 2003) [117, 118, 119] | Hexane and Methanol | S | Duraipandiyan et al., 2006 [120] | ||||

| 97 | Acalypha fruticosa | Chinni chedi | Aerial parts | Stomachic, attenuate (Nadkarni, 1976; Rastogi and Mehrotra, 1990–1994; Narasimhan, 2003) [117, 118, 119] | Hexane | P,S | Duraipandiyan et al., 2006 [120] | ||||

| 98 | Syzygium cumini | Naval pazham | Seed | Astringent, stomachic, diuretic, tonic and anti-diabetic (Nadkarni, 1976; Rastogi and Mehrotra, 1990–1994; Narasimhan, 2003) [117, 118, 119] | Methanol | S,K | Duraipandiyan et al., 2006 [120] | ||||

| 99 | Olax scandens | Kaattu pavalam | Leaves | Febrifuge (Nadkarni, 1976; Rastogi and Mehrotra, 1990–1994; Narasimhan, 2003) [117, 118, 119] | Hexane | K | Duraipandiyan et al., 2006 [120] | ||||

| 100 | Peltophorum pterocarpum | Malai porasu | Flower | Applied topically to treat wounds (Nadkarni, 1976; Rastogi and Mehrotra, 1990–1994; Narasimhan, 2003) [117, 118, 119] | Methanol | K | Duraipandiyan et al., 2006 [120] | ||||

KEY TO ABBREVIATIONS: Ef = Enterococcus faecium, K = Klebsiella pneumoniae, P = Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S = Staphylococcus aureus A = Acinetobacter baumannii, MRSA = Methicilin resistant Staphylococcus aureus, IRPA = Imipenem resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, ESBL-KP = Extended spectrum β lactamase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, ARKP = Ampicillin resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, Ec = E. cloacae, MDR-A = Multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, VRE = Vancomycin resistant E. faecium, Ea = E. aerogenes,∗ MβL P = metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa, MβL A = metallo-β-lactamase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii, VRE = vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus, VRS = vancomycin-resistant S. aureus, MDR-S = Multidrug resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

E. aerogenes has been changed to Klebsiella aerogenes.

Chart 1.

The above chart shows the number of plants with potential antimicrobial properties collected from each country during the period of 2006–2020.

The plant-derived extracts mentioned in this review were prepared in deionised water and/or diverse organic solvents such as methanol, chloroform, hexane, ethyl acetate, and so on. Alcoholic extracts of ethanol and methanol were the most common extracts used and they showed the highest antimicrobial properties. Antimicrobial assays such as Kirby Bauer Disc Diffusion and Agar well diffusion were performed to determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) to test the effectiveness of the extracts in MDR bacterial strains. MIC values of the extracts of the same solvent were varied even though all the extracts possessed similar antibacterial efficacy. This was seen because the bacterial inhibition activity is majorly dependent on the bioactive compound present in the extract. So, a difference in MIC between two plant extracts can be attributed to the presence of a different bioactive compound or different concentrations of the same bioactive compound. These bioactive compounds are essentially phytochemicals such as flavonoids, tannins, coumarins, triterpenes, alkaloids, phenylpropanoids, sterols and terpenoids.

Most of the plants showed specific inhibitory effects against one or two members of ESKAPE. However, a few displayed significant broad-spectrum antibacterial activity. These were: Martynia annua, Cynodon dactylon, Rauwolfia serpentine, Piper betle, Ehretia microphylla, Lantana camara, and Bridelia micrantha.

Therefore, it is vital to perform additional chemical analysis of the aforementioned plant extracts to determine their chemical composition and pin-point the exact phytocompounds responsible for antimicrobial activity. The plant extracts should be subjected to a series of pharmacological tests to ascertain their in vivo efficacy, cytotoxicity, interactions and any harmful side-effects.

4. Conclusion

Emergence of “superbugs” is a serious health problem due to escaping of antibiotics used for their treatment. Therefore, there is a need for the medicinal plants being exploited as a source for alternative medicines Studies focusing on the use of phytochemicals and plant extracts from different countries for the treatment of infections caused by ESKAPE pathogens, have been highlighted in this review.

However, further research needs be carried out regarding plant-derived active principles, for this knowledge to be translated into potential therapeutic drugs.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank our Principal (Ram Lal Anand College, University of Delhi) and college research grant committee for their constant support. I would also like to thank my colleagues for their upkeep.

References

- 1.Carr C., Smith A., Marturano M. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: how do the different criteria for diagnosis match up? Am. Surg. 2019;85(9):992–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giedraitienė A., Vitkauskienė A., Naginienė R., Pavilonis A. Antibiotic resistance mechanisms of clinically important bacteria. Medicina (Kaunas) 2011;47(3):137–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhen X., Lundborg C.S., Sun X., Hu X., Dong H. Economic burden of antibiotic resistance in ESKAPE organisms: a systematic review. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Contr. 2019;8:137. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0590-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boucher H.W., Talbot G.H., Bradley J.S. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! an update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;48(1):1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giamarellou H. Multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: how to treat and for how long. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2010;36(Suppl 2):S50–S54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . WHO report; 2017. Global Priority List of Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria to Guide Research.https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/global-priority-list-antibiotic-resistant-bacteria/en/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ranjalkar J., Chandy S.J. India's National Action Plan for antimicrobial resistance - an overview of the context, status, and way ahead. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care. 2019;8(6):1828–1834. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_275_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma Y.X., Wang C.Y., Li Y.Y. Considerations and caveats in combating ESKAPE pathogens against nosocomial infections. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 2019;7(1):1901872. doi: 10.1002/advs.201901872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magiorakos A.P., Srinivasan A., Carey R.B. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18(3):268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahmani M., Saki K., Shahsavari S. Identification of medicinal plants effective in infectious diseases in Urmia, northwest of Iran. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015;5(10):858–864. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cragg G.M., Newman D.J. Natural products: a continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1830(6):3670–3695. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samson O.A., Kenneth U., Paul A.A. Biogenic synthesis and antibacterial activity of controlled silver nanoparticles using an extract of Gongronema Latifolium. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019;237:121859. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aisida S.O., Ugwoke E., Uwais A. Incubation period induced biogenic synthesis of PEG enhanced Moringa oleifera silver nanocapsules and its antibacterial activity. J. Polym. Res. 2019;26:225. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ngozi M., Samson O.A., Awais A. Biosynthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles via a composite of Psidium guavaja-Moringa oleifera and their antibacterial and photocatalytic study. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2019;199:111601. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aisida S.O., Madubuonu N., Alnasir M.H. Biogenic synthesis of iron oxide nanorods using Moringa oleifera leaf extract for antibacterial applications. Appl. Nanosci. 2020;10:305–315. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Binawati G., Ilham M., Ida K. Biosynthesis copper nanoparticles using Blumea balsamifera leaf extracts: characterization of its antioxidant and cytotoxicity activities. Surfaces Interfaces. 2020;21:100799. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma Y.K., Singh H., Mehra B.L. Hepatoprotective effect of few Ayurvedic herbs in patients receiving antituberculus treatment. Indian J. Trad Know. 2004;3(4):391–396. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sankar M., Rajkumar J., Sridhar D. Hepatoprotective activity of heptoplus on isoniazid and rifampicin induced liver damage in rats. Indian J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2015;77(5):556–562. doi: 10.4103/0250-474x.169028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mangwani N., Singh P.K., Kumar V. Medicinal plants: adjunct treatment to tuberculosis chemotherapy to prevent hepatic damage. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandemir F.M., Yıldırım S., Kucukler S., Caglayan C., Darendelioğlu E., Dortbudak M.B. Protective effects of morin against acrylamide-induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity: a multi-biomarker approach. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020;138:111190. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madubuonu N., Aisida S.O., Ahmad I. Bio-inspired iron oxide nanoparticles using Psidium guajava aqueous extract for antibacterial activity. Appl. Phys. A. 2020;126:72. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emmanuel U., Samson O.A., Ameer A.M. Concentration induced properties of silver nanoparticles and their antibacterial study. Surfaces Interfaces. 2020;18:100419. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samson O.A., Abeeha B., Fawad M.K. Calcination induced PEG-Ni-ZnO nanorod composite and its biomedical applications. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020;255:123603. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walia K., Ohri V.C., Mathai D. Antimicrobial stewardship programme of ICMR. Antimicrobial stewardship programme (AMSP) practices in India. Indian J. Med. Res. 2015;142(2):130–138. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.164228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tacconelli E., Carrara E., Savoldi A. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18(3):318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santajit S., Indrawattana N. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. BioMed Res. Int. 2016;2016:2475067. doi: 10.1155/2016/2475067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pendleton J.N., Gorman S.P., Gilmore B.F. Clinical relevance of the ESKAPE pathogens. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2013;11(3):297–308. doi: 10.1586/eri.13.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Wamel W.J., Hendrickx A.P., Bonten M.J., Top J., Posthuma G., Willems R.J. Growth condition-dependent Esp expression by Enterococcus faecium affects initial adherence and biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 2007;75(2):924–931. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00941-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fiore E., Van Tyne D., Gilmore M.S. Pathogenicity of enterococci. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019;7(4) doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.gpp3-0053-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith D.M., Dou Q.P. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin inhibits DNA replication and consequently induces leukemia cell apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2001;7(6):645–652. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.7.6.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tong S.Y., Davis J.S., Eichenberger E., Holland T.L., Fowler V.G., Jr. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015;28(3):603–661. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Appelbaum P.C. Reduced glycopeptide susceptibility in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2007;30(5):398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navon-Venezia S., Kondratyeva K., Carattoli A. Klebsiella pneumoniae: a major worldwide source and shuttle for antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017;41(3):252–275. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Effah C.Y., Sun Tongwen, Liu Shaohua, Wu Yongjun. Klebsiella pneumonia: an increasing threat to public health. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12941-019-0343-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harding C.M., Hennon S.W., Feldman M.F. Uncovering the mechanisms of Acinetobacter baumannii virulence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;16(2):91–102. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tümmler B. Emerging therapies against infections with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. F1000Res. 2019;8:F1000. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.19509.1. Faculty Rev-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pang Z., Raudonis R., Glick B.R., Lin T.J., Cheng Z. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019;37(1):177–192. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morero N.R., Monti M.R., Argaraña C.E. Effect of ciprofloxacin concentration on the frequency and nature of resistant mutants selected from Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutS and mutT hypermutators. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55(8):3668–3676. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01826-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reza A., Sutton J.M., Rahman K.M. Effectiveness of efflux pump inhibitors as biofilm disruptors and resistance breakers in gram-negative (ESKAPEE) bacteria. Antibiotics (Basel) 2019;8(4):229. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8040229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmad I., Beg A.Z. Antimicrobial and phytochemical studies on 45 Indian medicinal plants against multi-drug resistant human pathogens. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001;74(2):113–123. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00335-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar V.P., Chauhan N.S., Padh H., Rajani M. Search for antibacterial and antifungal agents from selected Indian medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006;107(2):182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bibi Y., Nisa S., Chaudhary F.M., Zia M. Antibacterial activity of some selected medicinal plants of Pakistan. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2011;11:52. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-11-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cioch M., Satora P., Skotniczny M., Semik-Szczurak D., Tarko T. Characterisation of antimicrobial properties of extracts of selected medicinal plants. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2017;66(4):463–472. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.7002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2002. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2002-2005. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maroyi A. Traditional use of medicinal plants in south-central Zimbabwe: review and perspectives. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9:31. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harborne J.B., Baxter H. Taylor and Francis; London: 1995. Phytochemical Dictionary: A Handbook of Bioactive Compounds from Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cowan M.M. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999;12(4):564–582. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Panda S.K., Das R., Lavigne R., Luyten W. Indian medicinal plant extracts to control multidrug-resistant S. aureus, including in biofilms. South Afr. J. Bot. 2020;128:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cumberbatch A. 2011. An Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plant Usage in Salvador de Bahia. Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richwagen N., Lyles J.T., Dale B.L.F., Quave C.L. Antibacterial activity of Kalanchoe mortagei and K. fedtschenkoi against ESKAPE pathogens. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:67. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ngane R.A.N. Antibacterial activity of methanol extract and fractions from stem Bark of Bridelia micrantha (Hochst.) Baill. (Phyllanthaceae) EC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2019;7(7):609–616. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pallah O., Meleshko T., Tymoshchuk S., Yusko L., Bugyna L. How to escape 'the ESKAPE pathogens' using plant extracts. Sci Rise: Bio Sci. 2019;5–6(20-21):24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ishaq M.S., Hussain M.M., Afridi M.S. In vitro phytochemical, antibacterial, and antifungal activities of leaf, stem, and root extracts of Adiantum capillus-veneris. Sci. World J. 2014;2014:269793. doi: 10.1155/2014/269793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khan M.F., Tang H., Lyles J.T., Pineau R., Mashwani Z.U., Quave C.L. Antibacterial properties of medicinal plants from Pakistan against multidrug-resistant ESKAPE pathogens. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:815. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khan S., Khatoon S. Ethnobotanical studies on some useful herbs of haramosh and Bugrote valleys in Gilgit, Northern areas of Pakistan. Pakistan J. Bot. 2008;40(1):43–58. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayat M.Q., Khan M.A., Ashraf M. Ethnobotany of the genus artemisia, L. (Asteraceae) in Pakistan. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2009;7:147–162. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Santram L., Singhai A.K. Preliminary pharmacological evaluation of Martynia annua Linn. leaves for wound healing. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2011;1(6):421–427. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60093-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dhingra A., Chopra B., Mittal S. Martynia annua L.: a review on its ethnobotany, phytochemical and pharmacological profile. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2013;1(6):135–140. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar V., Van Staden J. A review of Swertia chirayita (Gentianaceae) as a traditional medicinal plant. Front. Pharmacol. 2016;6:308. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00308. Published 2016 Jan 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ahmad M., Sultana S., Fazl-I-Hadi S. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in high mountainous region of Chail valley (District Swat- Pakistan) J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014;10:36. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alam F., Us Saqib Q.N. Evaluation of Zanthoxylum armatum Roxb for in vitro biological activities. J. Tradit. Compl. Med. 2017;7(4):515–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abbasi A.M., Khan M., Ahmed M., Zafar M. Herbal medicines used to cure various ailments by the inhabitants of Abbottabad district, North West Frontier Province, Pakistan. Indian J. Trad. Know. 2010;9(1):175–183. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Malik T.A., Kamili A.N., Chishti M.Z. Breaking the resistance of Escherichia coli: antimicrobial activity of Berberis lycium royle. Microb. Pathog. 2017;102:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shobha K.L., Rao A.S., Pai K.S.R., Bhat S. Antimicrobial activity of aqueous and ethanolic leaf extracts of Anacardium occidentale. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018;11(12):474–476. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chandrasekharan D., Ballal R., Ballal B.B., Khetmalas M.B. Evaluation of selected medicinal plants for their potential antimicrobial activities against ESKAPE pathogens and the study of P-glycoprotein related antibiosis; an indirect approach to assess efflux mechanism. Int. J. Rec. Sci. Res. 2018;9(11A):29461–29466. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nayim P., Mbaveng A.T., Wamba B.E.N., Fankam A.G., Dzotam J.K., Kuete V. Antibacterial and antibiotic-potentiating activities of thirteen Cameroonian edible plants against gram-negative resistant phenotypes. Sci. World J. 2018;2018:4020294. doi: 10.1155/2018/4020294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Subramani R., Narayanasamy M., Feussner K.D. Plant-derived antimicrobials to fight against multi-drug-resistant human pathogens. 3 Biotech. 2017;7(3):172. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0848-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Masoumian M., Zandi M. Antimicrobial activity of some medicinal plant extracts against multidrug resistant bacteria. Zahedan J. Res. Med. Sci. 2017;19(11) [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Wyk B.E., Van Oudtshoorn B., Gericke N. Briza Publications; Pretoria: 2009. Medicinal Plants of South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Diederichs N., Mander M., Crouch N., Spring W., McKean S., Symmonds R. Inst Nat Reso; Gaborone: 2009. Knowing and Growing Muthi. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ghuman S. Antimicrobial activity, phenolic content, and cytotoxicity of medicinal plant extracts used for treating dermatological diseases and wound healing in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Front. Pharmacol. 2016;7:320. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Al-Bayati F.A. Isolation and identification of antimicrobial compound from Mentha longifolia L. leaves grown wild in Iraq. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2009;8:20. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-8-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Agarwal P., Agarwal N., Gupta R., Gupta M., Sharma B. Antibacterial activity of plants extracts against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. J. Microb. Biochem. Technol. 2016;8:5. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gulati R.K., Agarwal S., Agrawal S.S. Hepatoprotective studies on Phyllanthus emblica Linn. and quercetin. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 1995;33(4):261–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baliga M.S., Meera S., Mathai B., Rai M.P., Pawar V., Palatty P.L. Scientific validation of the ethnomedicinal properties of the Ayurvedic drug Triphala: a review. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2012;18(12):946–954. doi: 10.1007/s11655-012-1299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miller J.S. University of Natal Press; Pietermaritzburg: 1997. Zulu Medicinal Plants: an Inventory by A. Hutchings with A. H. Scott, G. Lewis, and A. B. Cunningham (University of Zululand) [Google Scholar]

- 77.Diederichs N., Mander M., Crouch N., Spring W., McKean S., Symmonds R. Institute of Natural Resources; Gaborone: 2009. Knowing and Growing Muthi. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Klos M., van de Venter M., Milne P.J., Traore H.N., Meyer D., Oosthuizen V. In vitro anti-HIV activity of five selected South African medicinal plant extracts. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124(2):182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rood B. Tafelberg; Cape Town: 1994. Uit die Veldapteek. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bruneton J., Cave A., Hatton C.K. Intercept; 1995. Pharmacognosy, Phytochemistry, Medicinal Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bacha K., Tariku Y., Gebreyesus F., Zerihun S., Mohammed A., Weiland-Bräuer N., Schmitz R.A., Mulat M. Antimicrobial and anti-quorum sensing activities of selected medicinal plants of Ethiopia: implication for development of potent antimicrobial agents. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16(1):139. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0765-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Miura Y., Chiba T., Miura S. Green tea polyphenols (flavan 3-ols) prevent oxidative modification of low density lipoproteins: an ex vivo study in humans. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2000;11(4):216–222. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(00)00068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Manandhar S., Luitel S., Dahal R.K. In vitro antimicrobial activity of some medicinal plants against human pathogenic bacteria. J. Trop. Med. 2019;2019:1895340. doi: 10.1155/2019/1895340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rajbhandari K.R. first ed. Ethnobotanical Society of Nepal; Kathmandu, Nepal: 2001. Ethnobotany of Nepal. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Manandhar N.P. Timber Press; Portland, Ore, USA: 2002. Plants and People of Nepal. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Singh A.G., Kumar A., Tewari D.D. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in Terai forest of western Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012;8:19. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Harvey A.L., Edrada-Ebel R., Quinn R.J. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14(2):111–129. doi: 10.1038/nrd4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Adedapo A.A., Jimoh F.O., Koduru S., Afolayan A.J., Masika P.J. Antibacterial and antioxidant properties of the methanol extracts of the leaves and stems of Calpurnia aurea. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2008;8:53. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Romha G., Admasu B., Gebrekidan T.H., Aleme H., Gebru G. Antibacterial ativities of five medicinal plants in Ethiopia against some human and animal pathogens. Hindawi Evid. Based Compl. Alternative Med. 2018;2018:10. doi: 10.1155/2018/2950758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wagate C.G., Mbaria J.M., Gakuya D.W. Screening of some Kenyan medicinal plants for antibacterial activity. Phytother Res. 2010;24(1):150–153. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alam N., Hossain M., Mottalib M.A., Sulaiman S.A., Gan S.H., Khalil M.I. Methanolic extracts of Withania somnifera leaves, fruits and roots possess antioxidant properties and antibacterial activities. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2012;12:175. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kamruzzaman Hakim Md., Hoq Obydul. A review on ethnomedicinal, phytochemical and pharmacological properties of Phyllanthus niruri. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2016;4(6):173–180. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Valle Demetrio L., Jr., Andrade J., Puzon J.J.M., Cabrera E.C., Rivera W.L. Antibacterial activities of ethanol extracts of Philippine medicinal plants against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015;5:532–540. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Martha R., Mitchell S., Solis R.V. Psidium guajava: a review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008;117:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fazal F., Mane P.P., Rai M.P., Thilakchand K.R., Bhat H.P., Kamble P.S., Palatty P.L., Baliga M.S. The phytochemistry, traditional uses and pharmacology of Piper Betel. Linn (Betel leaf): a pan-asiatic medicinal plant. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11655-013-1334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shukla A., Kaur A. A systematic review of traditional uses bioactive phytoconstituents of genus Ehretia. Asian J. Pharmaceut. Clin. Res. 2018;11(6) [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ulloa-Urizar G., Aguilar-Luis M.A., del Lama-Odría M.C., Camarena-Lizarzaburu J., Mendoza J.V. Antibacterial activity of five Peruvian medicinal plants against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015;5(11):928–931. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Darwish R.M., Aburjai T.A. Effect of ethnomedicinal plants used in folklore medicine in Jordan as antibiotic resistant inhibitors on Escherichia coli. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2010;10(9) doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-9. Published 2010 Feb 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Amenu D. Antimicrobial activity of medicinal plant extracts and their synergistic effect on some selected pathogens. Am. J. Ethnomed. 2014;1:18–29. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cuaresma A.L., Panaligan M., Cayco M. Socio-demographic profile and clinical presentation of inpatients with community acquired-methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) skin and soft tissue infection at the university of santo tomas hospital. Philippine J. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008;37(1):54–63. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tchana M.E., Fankam A.G., Mbaveng A.T. Activities of selected medicinal plants against multi- drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria in Cameroon. Afr. Health Sci. 2014;14(1):167–172. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v14i1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tanko Y., Yerima M., Mohammed A. Hypoglycemic activity of methanolic stem bark of adansonnia digitata extract on blood glucose levels of streptozocin-induced diabetic wistar rats. Int. J. Appl. Res. Nat. Prod. 2008;1(2):32–36. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kaboré D., Sawadogo-Lingani H., Diawara B., Compaoré C.S., Dicko M.H., Jakobsen M. A review of baobab (Adansonia digitata) products: effect of processing techniques, medicinal properties and uses. Afr. J. Food Sci. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 104.Djeussi D.E., Sandjo L.P., Noumedem J.A., Omosa L.K., T Ngadjui B., Kuete V. Antibacterial activities of the methanol extracts and compounds from Erythrina sigmoidea against Gram-negative multi-drug resistant phenotypes. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2015;15:453. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0978-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Olaleye, Tolulope M.O. Cytotoxicity and antibacterial activity of Methanolic extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa. J. Med. Plants Res. 2007;1(1):9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pattewar S.V., Patil D.N., Dahikar S.B. Antimicrobial potential of extract from leaves of Kalanchoe pinnata. Int. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. Res. 2013;4(12):4577–4580. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Watt J.M., Breyer-Brandwijk M.G. E. & S. Livingstone LTD: Edinburg and London; England: 1962. The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Johnson T. CRC Press LLC; Boca Raton: 1999. CRC Ethnobotany Desk Reference. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Van Wyk B.-E., Wink M. first ed. Briza Publications; Pretoria, South Africa: 2006. Medicinal Plants of the World. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nielsen T.R., Kuete V., Jäger A.K., Meyer J.J., Lall N. Antimicrobial activity of selected South African medicinal plants. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2012;12:74. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Palgrave K.C. Struik; Cape Town, South Africa: 1988. Trees of Southern Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Neuwinger H.D. Chapman & Hall; London, England: 1996. African Ethnobotany – Poison and Drugs. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Karunai Raj M., Balachandran C., Duraipandiyan V., Agastian P., Ignacimuthu S. Antimicrobial activity of Ulopterol isolated from Toddalia asiatica (L.) Lam.: a traditional medicinal plant. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140(1):161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pal S., Chaudhuri A.K. Studies on the anti-ulcer activity of a Bryophyllum pinnatum leaf extract in experimental animals. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1991;33(1-2):97–102. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(91)90168-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Biswas S.K., Chowdhury A., Das J., Karmakar U., Shill M. Assessment of cytotoxicity and antibacterial activities of ethanolic extracts of Kalanchoe pinnata Linn. (family: crassulaceae) leaves and stems. Int. J. Pharm. 2011;2(10):2605–2609. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Khan R., Islam B., Akram M., Shakil S., Ahmad A., Ali S.M., Siddiqui M., Khan A.U. Antimicrobial activity of five herbal extracts against multi drug resistant (MDR) strains of bacteria and fungus of clinical origin. Molecules. 2009;14(2):586–597. doi: 10.3390/molecules14020586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Nadkarni K.M. Popular Prakashan Bombay India; 1976. Indian Materia Medica. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rastogi R.P., Mehrotra B.N., Sinha S., Pant P., Seth R. Lucknow: Central Drug Research Institute and Publications & Information Directorate; New Delhi: 1990. Compendium of Indian Medicinal Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yoha Narasimhan S.N. Tamil Nadu Cyber Media Bangalore; India: 2003. Medicinal Plants of India. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Duraipandiyan V., Ayyanar M., Ignacimuthu S. Antimicrobial activity of some ethnomedicinal plants used by Paliyar tribe from Tamil Nadu, India. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2006;6:35. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.