Abstract

We analyzed 98 Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates collected in 2 regions of Algeria in 2015–2018 from 93 cases of pulmonary tuberculosis. We identified 93/98 isolates as M. tuberculosis lineage 4 and 1 isolate as M. tuberculosis lineage 2 (Beijing). We confirmed 4 isolates as M. bovis by whole-genome sequencing.

Keywords: tuberculosis and other mycobacteria, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis, whole-genome sequencing, Algeria, bacteria

In Algeria, interpreting tuberculosis (TB) incidence, estimated at 53–88 cases/100,000 population in 2017 (1), is limited by the fact that the diagnosis relies on microscopic examination of clinical samples. Isolates are presumptively identified as Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex based on colony phenotype.

We analyzed 98 sputum isolates identified as M. tuberculosis complex by 5 Tuberculosis and Respiratory Disease Control Service facilities in 2015–2018 (Appendix Table 1, Figure, ). Exact tandem repeat D analysis (2) confirmed these 98 isolates as M. tuberculosis complex. Large-sequence polymorphism analysis using PCR sequencing of genomic regions RD105, RD239, and RD750 and of the polyketide synthase gene pks15/1 (3) yielded 88 (89.8%) M. tuberculosis sensu stricto Euro-American lineage 4 isolates and 1 East Asian lineage 2 (Beijing) isolate. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of 5 RD deletion–free unidentified isolates indicated that these 5 isolates, P9982(ERR3588223), P9983(ERR3588225), P9985(ERR3588243), P9984(ERR3588246), and P9986(ERR3588247), were M. tuberculosis sensu stricto Euro-American lineage 4. We conducted WGS analysis using TB-profiler for M. tuberculosis online tool (https://tbdr.lshtm.ac.uk/upload) for lineage and sublineage determination. Altogether, M. tuberculosis lineage 4 was the predominant lineage in the 5 Algerian departments and the sole lineage documented in Bgayet, Tizi-Ouzou, and Medea (Appendix Table 2); it was found to be the cause of pulmonary TB in 79/93 (85%) cases, pleural TB in 11 (12%) cases, and lymph node TB in 3 (3%) cases. These observations updated those issued from a previous study conducted in 14 departments including 114 (88%) cases of pulmonary localization and 15 cases (12%) of extrapulmonary localization (4). In a later study, spoligotyping revealed that most isolates belonged to M. tuberculosis Euro-American lineage 4; the Haarlem clade accounted for 29.5% of studied isolates; the Latin American-Mediterranean clade, 25.6%; and the T clade, 24.8% (4). In our study, 1 M. tuberculosis Beijing strain was isolated from a bronchial fluid sample collected in Blida from the location at which 15 M. tuberculosis Beijing isolates had been identified ≈10 years earlier from 14 workers from Algeria and 1 from China (5). Our observation suggests that 10-year circulation of M. tuberculosis Beijing strain in the community in Blida area most probably followed immigration of workers from China employed in the construction sector.

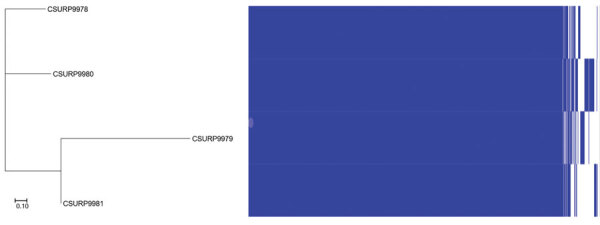

WGS analysis of 4 additional isolates exhibiting a 6-bp deletion in the pks15/1 gene identified them as M. bovis. Using a Roary pangenome pipeline (https://sanger-pathogens.github.io/Roary), we found that M. bovis CSURP9981 grouped with M. bovis CSURP9979 and that M. bovis CSURP9980 grouped with M. bovis CSURP9978 (Figure). Further analysis based on the 3,732,808-bp core genome detected 3,761-bp (0.1%) of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between the 4 isolate genomes. Whole-genome sequences of M. bovis strains in the study have been deposited in GenBank (sequence P9978, accession no. ERR3587501; P9979, no. ERR3587591; P9980, no. ERR3587597; and P9981, no. ERR3588222).

Figure.

Pangenome-based tree of 4 human Mycobacterium bovis isolates, Algeria. The tree was generated by Roary (https://sanger-pathogens.github.io/Roary) from binary gene presence or absence in the accessory genome. Scale bar indicates 10% sequence divergence.

All 4 patients had pulmonary TB and had no detectable lymph node swelling and no scrofula (6). Two case-patients in Blida were a 27-year-old unemployed man and a 60-year-old taxi driver who both declared that they did not consume raw milk and had no contacts with cattle; a neighbor of the 60-year-old patient was a butcher with whom he spent a lot of time. Two case-patients in Ain Defla were 18-year-old and 43-year-old housewives living in 2 different rural areas. The interviews of these patients did not reveal contacts with cattle. Identification of human cases of M. bovis was unexpected because in 50 years, only 7 cases of M. bovis human infection have been reported in Algeria: 3 cases of pulmonary TB and 2 cases of cervical lymphatic TB detected in a total of 1,183 (0.4%) phenotypically identified M. bovis isolates (7), and 2 additional cases reported in 2009 (8).

M. bovis TB is clinically, pathologically, and radiologically indistinguishable from M. tuberculosis; diagnosis requires accurate identification of the causative mycobacterium, most efficiently by using WGS. Our report illustrates pitfalls in precisely tracing the natural history of M. bovis TB in patients, including sources, routes of transmission, and primary route of entry, which may determine the pathology of the infection. Zoonotic M. bovis TB was most often transmitted to humans by the consumption of M. bovis–contaminated dairy products that caused lymphatic TB, eventually becoming pulmonary TB (9). We previously reported a hidden circumstance for contacts with M. bovis–infected animals, tracing 1 M. bovis pulmonary TB case in a patient in Tunisia to contacts with an infected sheep during religious festivities in 2018 (10). In the case we report here, foodborne transmission cannot be ruled out, but it is possible that this may be a rare case of aerosol transmission.

Algeria is a bovine TB–enzootic country. We recommend comparing the genome sequences from the 4 patients reported here with those of future bovine isolates in the same departments to trace zoonotic M. bovis TB in Algeria and contribute to the understanding of its natural history.

Additional information about Mycobacterium bovis pulmonary tuberculosis in Algeria.

Acknowledgments

We thank Graba L., Lamri Zahir, Cherair Ali, and Kerrouche Moussa and those who are responsible for the Tuberculosis and Respiratory Disease Control Service facilities of Tizi Ouzou for their valuable assistance. We also thank Mohamed Rahal, Asma Aiza, and especially Sofiane Tahrikt.

Biography

Dr. Tazerart is a veterinarian with a magister degree in animal epidemiology. He is an instructor at Blida University and is a PhD student at Tiaret University, Algeria. His research interests include bovine and human tuberculosis in Algeria, with a focus on characterization of animal and human M. bovis strains.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Tazerart F, Saad J, Niar A, Sahraoui N, Drancourt M. Mycobacterium bovis pulmonary tuberculosis, Algeria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Mar [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2703.191823

These authors equally contributed to this work.

References

- 1.Bouziane F, Allem R, Sebaihia M, Kumanski S, Mougari F, Sougakoff W, et al. ; CNR-MyRMA. First genetic characterisation of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Algeria. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;19:301–7. 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Djelouadji Z, Raoult D, Daffé M, Drancourt M. A single-step sequencing method for the identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex species. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e253. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gagneux S, Small PM. Global phylogeography of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and implications for tuberculosis product development. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:328–37. 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70108-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ifticene M, Kaïdi S, Khechiba MM, Yala D, Boulahbal F. Genetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains isolated in Algeria: Results of spoligotyping. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2015;4:290–5. 10.1016/j.ijmyco.2015.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ifticene M, Gacem FZ, Yala D, Boulahbal F. Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotype Beijing: About 15 strains and their part in MDR-TB outbreaks in Algeria. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2012;1:196–200. 10.1016/j.ijmyco.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forget N, Challoner K. Scrofula: emergency department presentation and characteristics. Int J Emerg Med. 2009;2:205–9. 10.1007/s12245-009-0117-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Beco O, Boulahbal F, Grosset J. [Incidence of the bovine bacillus in human tuberculosis at Algiers in 1969] [in French]. Arch Inst Pasteur Alger. 1970;48:93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gharnaout M, Bencharif N, Abdelaziz R, Douagui H. Tuberculosis from Mycobacterium bovis: about two cases [in French]. Rev Mal Respir. 2009;26:141 https://www.em-consulte.com/rmr/article/197004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michel AL, Müller B, van Helden PD. Mycobacterium bovis at the animal-human interface: a problem, or not? Vet Microbiol. 2010;140:371–81. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saad J, Baron S, Lagier JC, Drancourt M, Gautret P. Mycobacterium bovis pulmonary tuberculosis after ritual sheep sacrifice in Tunisia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1605–7. 10.3201/eid2607.191597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional information about Mycobacterium bovis pulmonary tuberculosis in Algeria.