Abstract

The COVID-19 outbreak has been associated with significant occupational stressors and challenges for healthcare workers (HCWs) including the risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Many reports from all over the world have already found that HCWs have significant levels of self-reported anxiety, depression and even symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Therefore, supporting mental health of HCWs is a crucial part of the public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim of the present review is to ascertain the interventions put in place worldwide in reducing stress in HCWs during the COVID-19 outbreak. We evidenced how only few countries have published specific psychological support intervention protocols for HCWs. All programs were developed in university associated hospitals and highlighted the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration. All of them had as their purpose to manage the psychosocial challenges to HCW's during the pandemic in order to prevent mental health problems.Whether one program offers distinct benefit compared to the others cannot be known given the heterogeneity of the protocols and the lack of a rigorous protocol and clinical outcomes. Further research is crucial to find out the best ways to support the resilience and mental well-being of HCWs.

Keywords: SARS-COV-2, COVID-19, Health Care Workers, Mental health, Psychological interventions, Psychological protocols

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to grow, and as of February 15th, more than 100 million cases and more than 2 million deaths have emerged globally (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). From the beginning, the virus and its related disease represented a hard challenge for Health Care Workers (HCWs) with a huge number of patients who poured into hospitals at the same time which determined increased workload and physical exhaustion in contrast with the scarce informations about the virus itself (transmission, symptoms, protection, immunity, hospitalization criteria, recovery etc.) that brought to make ethically difficult decisions on the rationing of care (Buselli et al., 2019, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c; Orsini et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020). In addition, SARS-COV-2 shows a high transmission from person to person through several different routes, which determined, especially in the first wave of contagion characterized from inadequacy of personal equipments, a high rate of infection among HCWs themselves and the risk of infection of friends and relatives that determined an increase feeling of isolation and stigmatization (Huang et al., 2020; De Sio et al., 2020; Buselli et al., 2019, 2020a; Ramaci et al., 2020). Some authors supposed that HCWs resilience was further compromised by conflicting thoughts about balancing their roles as healthcare providers and family duties. These mixed feelings could determine a sense of guilt about potentially exposing their families to infection by working during the COVID-19 emergency (Buselli et al., 2020a, 2020b; Firew et al., 2020; Godderis et al., 2020; Jin et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Pfefferbaum & North, 2020; Shanafelt et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2020). Further, HCWs demonstrated to be also exposed to the emotional residue or strain of exposure to working with those suffering from the consequences of such a traumatic and unprecedented event. HCWs are required to face patients dying alone and having to communicate this to their families, which can be traumatizing and produces a high risk of extreme stress and burnout (Patel et al., 2018; Waterman et al., 2018, Buselli et al 2020a, 2020b, 2020c).

Reports from all over the world have already ascertained that HCWs have significant levels of self-reported anxiety, depression, insomnia and even symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (Buselli et al., 2020a, 2020b; Digby et al., 2020; Firew et al., 2020; Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020; Maiorano et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Trumello et al., 2020; Vagni et al., 2020) and a recent canadian meta-analysis further evidenced that the prevalence of insomnia seems to be more than two times higher among HCWs than in the general population (Cenat et al., 2021).

In the current healthcare context, signs of occupational stress are an important public health concern (Walton et al., 2020). The prevention of high stress levels in the work environment is imperative in efforts to improve the quality of the work-life balance, even in the face of a long pandemic scenario and its consequences through years. (Marine et al., 2006; Ruotsalainen et al., 2008; Troyer et al., 2020). After the pandemic ends, HCWs may develop even more severe mental health problems (Cenat et al., 2021).

The scientific community has pointed out that there is a need to develop tailored mental health interventions for HCWs (Holmes et al., 2020). For several years the WHO urged on this issue and from the very beginning of the pandemic has emphasized the extremely high burden on HCWs in the contest of occupational medicine and called for action to address the needs and measures needed to save lives and prevent a serious impact on physical and mental health of HCWs (WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19), WHO Health Worker Occupational Health 2021). Protecting clinicians’ mental health in the aftermath of COVID-19 is, indeed, crucial and requires an evidence-based approach to developing and disseminating comprehensive clinicians’ mental health support (Schwartz et al ., 2020).

Many health organizations have already committed resources to the well-being of HCWs, but only a few published their protocols of intervention. The majority opted for helpline services, usually applicable and effective for urgent social and psychological problems. Positive examples of these come from China as they first experienced the COVID-19 outbreak and fully recognized the importance of psychological assistance in emergency situations (Zaka et al., 2020). Specifically, within hospitals, psychological services were offered to medical staff and patients in the form of psychological education and face-to-face psychological interventions (Wang et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020).

In the era of evidence-based practice, we need practice-based evidence especially in the regard of a completely new burden psychosocial issue (Barber et al., 2016; Cenat et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020). A recent review evidenced how the majority of studies regarding psychological needs for HCWs recommended psychosocial interventions with strong emphasis on the need for additional psychosocial support with effective strategies and precise care were the target of interventions were predominantly stress and fear (Muller et al., 2020). Now that Europe is in the middle of the second wave of infections and hospitals are on the brink of collapsing, local institutions need a rapid and practical approach which can be easily replicableamong different HCWs groups and contests or there is a risk of not closing the gap between best evidence and best practice in light of the current unprecedented situation (Buselli et al., 2020a). In this regard the aim of the present review is to ascertain the interventions put in place worldwide in reducing stress in HCWs during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Health care well-being efforts fall into three interrelated categories: individual, organizational and societal intervention areas. Psychological support for HCWs should focus on organisational as well as individual characteristics, with a broader goal of maintaining an organisational culture of resilience. Prior pandemics have demonstrated that the context of the organisation has powerful effects on psychological outcomes for the workforce (Blake et al., 2020). Resources have traditionally been put towards supporting staff once they have developed mental health disorders. Consistently, the actual emergency requires a shift of focus from the individual to the organisation (Walton et al., 2020).

In light of its principal objective, this review focused on hospital organizational protocols specifically designed for HCWs. We selected four main focus points: type of intervention, organization of the intervention, departments involved and outcomes of the intervention.

The goal was to try to answer to the following questions:

-

-

Have psychological support protocols for HCWs been developed globally?

-

-

-How many such protocols exist?

-

-

-What are these protocols and are there appreciable outcomes to be shared by the scientific community?

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

We conducted an electronic search in the following databases: Medline/PubMed, Psychinfo, Cochrane library and Enbase. Reference sections of the identified papers were eventually checked for additional studies. Unpublished studies were excluded from the analysis but they may have been cited in discussion.

Our digital search strategy involved the following keywords “COVID-19”, “Health Care Workers (HCWs)”, “hospital staff”, “medical staff” and “mental health” in different combinations with the at least one of the two following words: “protocol” and/or “intervention” and covered the period between March 2020 (being the month during which the WHO declared COVID-19 a public health emergency of international concern) and October 2020.

2.2. Study selection

We included only English language papers that had met the following main inclusion criteria: the study reported a protocol of intervention to address mental health of HCWs during COVID-19 outbreak. Selected studies were addressed comprising the three main objectives outlined above. Due to the nature of the studies and the high degree of heterogeneity between protocols we were unable to undertake a formal analysis Therefore, we opted for a narrative approach with a description and comparison between studies. Some of the review authors (MC, AV, and SB) independently inspected all English language citations from the search to identify relevant titles and abstracts. We obtained the full reports of the papers for more detailed inspection, before deciding whether the paper met the review criteria. We resolved any disagreement by consensus.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of studies

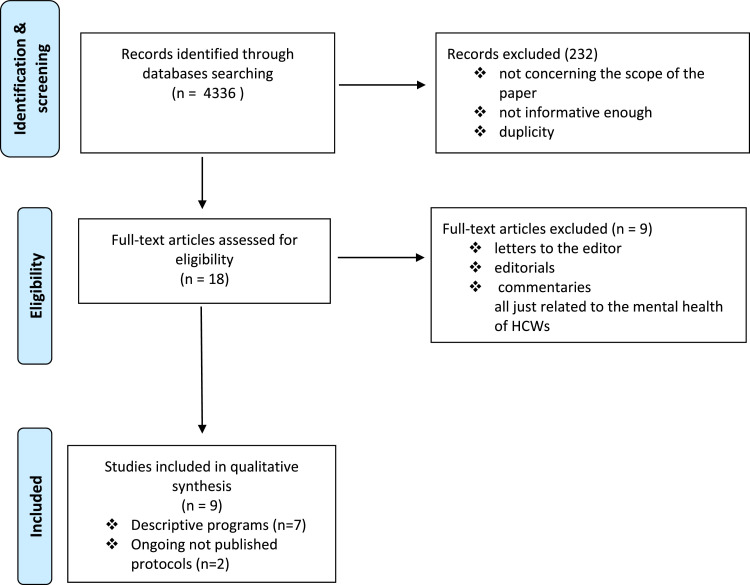

The search retrieved 4336 results. We then excluded titles with the following features: a) subject matter that was not relevant to the scope of this paper b) not informative enough c) duplication.

Eighteen studies were selected as potentially relevant after screening of titles and abstracts. On reviewing the above citations, some were discarded because they consisted of letters to the editor and editorials or commentary related to the mental health of HCWs and COVID-19 and often were just recommendations made on surveys. As a result, seven studies were included in the review and other 2 papers were discussed separately as consisting in ongoing clinical trials. (Albott et al., 2020; Buselli et al., 2020a; Chen et al., 2020; DePierro et al., 2020; Mellins et al., 2020; Sulaiman et al., 2020; Lefèvre et al., 2021). See figure 1 . PRISMA flow chart of the study selection process.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow-chart of study selection process

3.2. Characteristics of the included programs

We identified seven published programmes and 2 ongoing trials. Among the published papers, emerged in particular three programmes from North America, one from Italy, one from France, one from China one from Malaysia. All programmes were developed from University hospitals and presented an identification name, except for the Chinese programme. The majority of programmes were developed by academic, tertiary care hospitals. Although program activities varied, most of the programs incorporated concepts of psychosocial support as team training, peers and institutional support, just one opted for a more clinical intervention and other two proposed more concrete measures for the satisfaction of immediate daily needs (provision of food, rest breaks, decompression time, and adequate time off). No published papers except from one presented outcomes of the interventions put in place. The French program was the only one that presented a qualitative feedback of the offered service obtained by an online survey.

3.3. Program objectives

These organisational provisions of psychological support all have the common purpose of managing psychosocial challenges among HCWs and prevention of psychiatric diseases related to COVID-19 through different methods, and with several professionals involved.

The Second Xiangya Hospital, workplace of the chairman of the Psychological Rescue Branch of the Chinese Medical Rescue Association, and the Institute of Mental Health, the Medical Psychology Research Center of the Second Xiangya Hospital, and the Chinese Medical and Psychological Disease Clinical Medicine Research Center encountered obstacles in providing HCWs psychological support. Therefore, they performed a short survey of immediate needs and, accordingly, the measures of psychological intervention were adjusted to more practical items and facilities directly requested by the staff (Chen et al., 2020).

The department of Psychological Medicine of University of Malaya, and the Counselling and Psychological Management Unit of University Malaya Medical Centre decided for a remote Psychological First Aid (PFA) protocol consisting in tele-psychiatry via WhatsApp mobile application and phone calls (Sulaiman et al., 2020).

Columbia University Irving Medical Center developed three categories of service: Peer Support Groups, One-to-One Peer Support Sessions and a series of Grand Rounds and Town Halls to accommodate larger audiences and departmental need. They also developed a website for information on offerings, with a curated list of internal and external resources for HCWs. The website included guidance on managing stress and anxiety, provided links to mindfulness, meditation, and exercise apps, and localized information on trauma and grief, parenting and caregiving in the context of COVID-19, maintaining resilience, accessing mental health services, and other support resources (Mellins et al., 2020).

The Mount Sinai Hospital System in New York, which comprises eight member hospitals, founded the Center for Stress, Resilience and Personal Growth (CSRPG) in April 2020. CSRPG provided mental health screening, resilience-promoting workshops, personalized service referrals, and, in parallel, presented also a research arm focused in the psychobiology of human resilience. They developed a mental health and wellness mobile app to allow HCWs to self-screen for mental health symptoms, track progress over time, and connect to CSRPG wellness resources (DePierro et al., 2020).

The University of Minnesota Medical Center developed a psychological resilience intervention that is derived from the Battle Buddy system developed in the US Army and that presents elements of the Anticipate-Plan-Deter (APD) model for mitigating psychological consequences for HCW who are responding to disasters (Albott et al., 2020).

The Occupational Health Department of Pisa University Hospital developed a protocol with two arms. One arm to monitor workers who already suffered from psychiatric and psychological problems prior to the pandemic, and the second arm to provide rapid and targeted help to HCWs directly involved in the emergency (Buselli et al., 2020a).

The administrative management teams in collaboration with medical and auxiliary workers of Cochin University hospital in Paris organized a place called the Bulle (bubble) which represented a safe place for the whole hospital staff for support and well-being within the hospital, combining a place to talk and a place for physical movements (Lefèvre et al., 2021).

Specific characteristic of the included studies were summarized in Tables 1 and 2 .

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies

| Country | China | Malaysia | U.S.A (New York) | U.S.A (New York) | U.S.A (Minnesota) | Italy | France |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention name | - | Remote Psychological First Aid Protocol | CopeColumbia | Center for Stress, Resilience and Personal Growth (CSRPG) | Battle Buddie | PsiCovid19 | The Port Royal Bubble |

| Type of hospital | Second Xiangya Hospital | University of Malaya (UM) University and Malaysia Medical Centre (UMMC) | Academic, tertiary care Medical Center | The MSHS: eight member hospitals | Academic, tertiary care Medical Center | Academic, tertiary care Medical Center | |

| Departments involved | Psychological Rescue Branch (Chinese Medical Rescue Association) and the Medical Psychology Research Center | The department of Psychological Medicine, UM, and the Counselling and Psychological Management Unit, UMMC | Department of Psychiatry in collaboration with hospital leadership | Office of Well-being and Resilience, Psychiatry Department and other hospital areas | Department of Anesthesiology, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences | Occupational Health Department in collaboration with hospital leadership | Administrative management teams in collaboration with medical and auxiliary workers |

| Type of intervention | Online courses to guide medical staff to deal with common psychological problems; psychological assistance hotline to provide guidance and supervision to solve psychological problems; group activities to release stress | Online promotion and awareness campaigns to minimize stigma; to measure quantitatively the level of depression, anxiety, distress, and burnout in frontliners through online assessment while maintaining confidentiality; to provide access to more intensive intervention for those who require it | A program focused on providing peer psychological support, mitigating emotional fatigue, and enhancing resilience | A framework of staff support response based on a hierarchy of need | An approach where were put resources directly into the hands of the HCWs, by providing them with 2 key elements: a Battle Buddy to provide peer support, and a mental health consultant assigned to the unit . Peer supporters (the Battle Buddy) who have similar levels of responsibility, life experience, and authority |

Multidisciplinary approach that includes both occupational physicians and mental health professionals to enhance HCWs’ ability to follow prevention procedures in the context of occupational risks | A warm caring welcome that promotes attention, listening, conversations, exchanges, empathetic support and the ability to participate in comforting, relaxing, or low-impact physical activities (massage therapy, ilates or strength training etc). |

| Services | Hospital provided a place for rest; guaranteed food and daily living supplies; helped staff to video record their routines in the hospital to share with their families; arranged pre-job training; developed detailed rules on the use and management of protective equipment to reduce worry; arranged leisure activities and training on how to relax. Counsellors regularly visited the rest area to listen to difficulties or stories and provide support accordingly | Tele-psychiatry via WhatsApp mobile application and phone calls. Guidelines adapted from the “Remote Psychological First Aid (PFA) during the COVID-19 outbreak” by the International Federation of Red Crescent Societies. This guideline applies the principles of “Look, Listen, Link” using phones and an on-line platform. It includes the assessment of the current risk and status of the HCW following referral; empathic listening; providing a link to a social support system and access to further intensive care as needed. To provide psychological support and accessible resources to ease the transition to normalcy based on the principle actions of contact, comfort, calm, concern, care, connection, coping, and collaboration |

Peer Support Groups; Leaders groups; Virtually-presented talks, focusing on topics (eg.,managing stress and anxiety, trauma, loss and grief, and strategies for supporting self-care and emotional well-being) and also a website with useful links to external resources |

Meeting series of manualized peer-co-led resilience workshops, centered on one of evidence-based resilience factors. Each attendee will make an individualized resilience plan and may opt to receive individual coaching with a staff clinician. Barriers to care were reduced by developing one central telephone number for all HCW mental health referrals. A mental health and wellness mobile app was developed in approximately one month. The app allows workers to self-screen for mental health symptoms and track progress. | A multilevel approach for bringing resilience interventions and mental health resources through focused peer support (Battle Buddies), unit-specific small group discussions (Anticipate-Plan), and additional individual support, if needed. APD model: cognitive and emotional inoculation for the stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic |

Monitoring of Psychopathological parameters in HCWs already under psychiatric/psychological treatment since before the COVID-19 outbreak; attention to HCWs reported by triage psychologists; evaluation employee's fitness for work in “COVID” or “non-COVID” units. In the event of any of suitability problems, the worker is reported to the hospital occupational physician |

Offered the whole staff a place for support and well-being within the hospital, combining a place to talk and a place for physical movement. Open all week, from nine in the morning to nine at night .Hospital employees can sign up for activities online or just come to the reception area to participate. The program is organized around four specific areas, three rooms, and the garden |

Table 2.

Aims, results and future outcomes

| China | Medical staff were reluctant to participate in the group or individual psychology interventions provided to them. Moreover, individual nurses showed excitability, irritability, unwillingness to rest, and signs of psychological distress, but refused any psychological help and stated that they did not have any problems. Many staff mentioned that they did not need a psychologist, but needed more rest without interruption and enough protective supplies. Finally, they suggested training on psychological skills to deal with patients’ anxiety, panic, and other emotional problems. |

| Malaysia | Still in progress during the publication process. The intended outcome of PFA services, remotely for now, must be readily available to provide psychological support and accessible resources to ease the transition to normalcy. To encourage healthcare workers to get psychological help through online promotion and awareness campaigns and to minimize stigma; to measure quantitatively the level of depression, anxiety, distress, and burnout through online assessment; to provide access to more intensive intervention for those who require it; to review and evaluate the protocol within a stipulated time frame. |

| U.S.A (New York) | One hundred and eighty six groups were conducted. Group participants and facilitators determined the need/desire for additional meetings (ranged from 1 to 13). Thematic similarities emerged: anxiety and uncertainty and themes of grief, loss, and trauma loomed large due to the severity of illness and volume of patient deaths and compounded by personal losses of family members and friends. Some HCWs expressed anger, feelings of moral distress as healers without known treatments or ways to prevent so many deaths. |

| U.S.A (New York) | Still in progress during the publication process. Services address the full spectrum of mental health presentations that are anticipated, including those workers who are doing well and want additional support and those struggling more with active psychological symptoms. As described below, CSRPG provides mental health screening, resilience-promoting workshops, and personalized service referrals. In parallel to its employee-facing services, CSRPG also has a research arm that draws upon MSHS's expertise in the psychobiology of human resilience. An initial “class” of 41 peer co-leaders completed training sessions in May and June 2020. Training comprised an overview of the science of resilience, review of workshop materials, and participation in at least one practice meeting focused on a resilience factor. Peer leaders will then co-facilitate workshops with a clinical social worker, psychiatrist, psychologist, or chaplain. |

| U.S.A (Minnesota) | Still in progress during the publication process. The intended outcome of these Battle Buddy relationships is that those with similar backgrounds can discuss daily challenges and successes with another peer who understands and appreciates the issue. The Battle Buddy, more than a spouse or other loved one, understands the significance of issues and challenges faced in the COVID-19 clinical setting and provides useful insights and recommendations. With practice, these daily conversations become mutually beneficial to the Battle Buddies, allowing work issues to remain at work, and leaving home environments as places of rest, recuperation, and relaxation. |

| Italy | Still in progress during the publication process. 81% were already monitored by the team. 60% of the total received a remodeling of a previous therapeutic program.7% passed from a psychiatric therapy to a combination therapy. Complained of emotional distress, characterized by anxiety, as a manifestation of both the fear of contagion and of isolation, anger fatigue, irritability, cognitive dysfunction, rapid mood swings and often in association with a lack of meta-cognitive abilities and of coping strategies to face such as a stressful situation. Some reported difficulties in work relationships |

| France | The aim was to offer staff a a space that is outside the walls and outside time:the walls are those in the ICU, acute care rooms, and medical departments. The time was that before the epidemic,Authors collected feedback through a qualitative survey. They overall collected a positive response from HCWs |

3.4. Ongoing trials

The first ongoing trial is named Recharge and is a randomized controlled trial born by the collaboration of University of New South Wales and University of Zurich. It is an abbreviated online version of Problem Management Plus, an evidence-based intervention that helps to cope with stress in times of crisis specifically developed for HCWs. The program teaches people three strategies to manage acute stress (a: managing stress, b: managing worry, c: meaningful activity). It includes psychoeducation, arousal reduction techniques, managing worries and problem-solving skills, behavioral activation, and enhancement of meaningful activities, which are all based on the principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy. The main outcome of the study is the evaluation of the efficacy of the program to reduce stress in HCWs and enhance their work performance. (Morina, 2020)

The second trial is just registered but not yet started. It should be a Canadian randomized controlled trial based on a Virtual Peer Support Platform. The intervention program will be shaped on the BASICS, a guide for supporting resilience against burnout, developed by the Ontario Medical Association Physician Health Program, as well as the Person-Environment-Occupation (PEO) model, a transactive approach to modelling occupational performance issues in the field of Occupational Therapy. The focus of the method are group therapy sessions (Samaan (Zena), 2020).

4. Discussion

The present review has tried to summarize the interventions specific designed for enhancing mental health care for HCWs in order to face COVID-19 psychological challenges. The aim of this review was to synthesise evidence-based informations through answers to three questions: (1) have protocols developed worldwide to face psychological distress among HCWs after COVID-19 outbreak? (2) how many such protocols exist? (3) what are these protocols and what results have they shown in terms of public health ? We believe that answering these questions, and thereby highlighting these protocols, is fundamental because psychological problems among HCWs could affect their attention, understanding or decision-making, and that protocols to limit such effects could prevent more serious psychological impairments and, at the same time, enhance adaptation skills and promote personal empowerment useful to face a long next phase (Zaka et al., 2020).

Unfortunately, we evidenced how only few countries have published specific psychological support intervention programs for HCWs despite the WHO's urgent call for tailored and culturally sensitive mental health interventions (Holmes et al., 2020). The majority of the information provided by the literature comes from surveys and cross-sectional observational studies. Furthermore, the published programs did not provide a simultaneous evaluation of the protocols using both a clinical and a control group to strengthen the methods adopted and this lowers the quality of the published clinical experience. The only two registered protocols retrieved form study searching seem not to be well developed since they are not updated for several months and they seem to have stopped at the recruiting stage. Regarding to this, only The Mount Sinai Hospital System seized the opportunity to create a new department, with both a clinical and a research arm, with the aim of continuing to invest in the well-being of HCWs even at the end of the emergency and they could provide interesting results in the next future (DePierro et al., 2020).

All the programmes highlighted the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration and the whole protocols, except for the CopeColumbia, were developed in a multidisciplinary scenario, but only the Italian programme addressed COVID-19 psychosocial issue from an occupational medicine perspective which could be a way to minimize the stigma associated to psychosocial distress and psychological interventions (Buselli et al., 2020a).

Only the Chinese programme evidenced a modification of intervention protocols on the basis of preliminary feedback received by HCWs. The Chinese programme was the first to address the new psychosocial burdens brought about by the pandemic and paved the way for health institutions and even governments to not limit their response only to necessary medical and economic actions, but also to implement parallel psychological assistance measures (Wang et al., 2020). A similar approach was used by the French whose intervention is based on the need to overcome isolation, boredom and the impossibility of relaxing with one's family and friends,and of exercising and spending time outside (Lefèvre et al., 2021).

Taking advantage of the difficulties encountered in China in proposing a psychological support service, the University of Minnesota Medical Center proposed a more groundbreaking approach taken from the military framework. They developed a psychological resilience intervention founded on a peer support model (Battle Buddies) developed by the United States Army. The assumption is that, similar to battlefield conditions, HCWs are confronted, on one hand, with ongoing uncertainty about capacities, resources and risks, and on the other, with suffering, death, and threats to their own safety (Albott et al., 2020). The Battle Buddy is not intended to be a mental health professional and the conversations between Battle Buddies are not confidential therapy sessions. If a Battle Buddy observes excessive anxiety or other maladaptive behaviors, only then will be offered mental health consultation. The intended outcome of these Battle Buddy relationships is that those with similar backgrounds can discuss daily challenges and successes with another peer who understands and appreciates the issue. With practice, these daily conversations become mutually beneficial to the Battle Buddies, allowing work issues to remain at work, and leaving home environments as places of relaxation (Albott et al., 2020; Shanafelt et al., 2020).

Likewise the Italian group from the University Hospital of Pisa sought a personalized way to overcome the limitations highlighted in China. Already aware of the Chinese observations, the Italian group elected not to promote immediate interventions designed for everyone but to wait for individual requests from workers and to help them from an occupational (and non-pathological) perspective in addition to the monitoring of physical symptoms, laboratory and microbiological tests (Buselli et al., 2020a).

Finally, the strategy adopted by Malaysia was based on a rapid adaptation of the remote Psychological First Aid (remote PFA) of the International Federation of Red Crescent Societies. A guideline that apply the principles of “Look, Listen, Link” using phones and an on-line platform (Sulaiman et al., 2020). Digital approaches focused specifically on supporting the psychological wellbeing of HCWs were studied also by English groups (Blake et al., 2020).

Whether one program offers distinct benefit compared to the others cannot be known given the heterogeneity of the programs and the lack of standardized protocols with a robust methodology and the lack of clinical outcomes. They were all developed during a rapidly evolving situation and so they prioritized clinical needs over research methods. Even a recent Cochrane review, investigating the effects of interventions supporting the resilience and mental health of frontline HCWs during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic from 2002 onwards, did not find any evidence about how well different strategies work. (Pollock et al., 2020). Given the evidence of the risk of short and long-term psychological consequences and the impact on job performance and quality of care, psychological protocols for HCWs should be urgently implemented (Chen et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020; Zaka et al., 2020).

This review should be considered in light of some limitations. First, although many mental health initiative have been urged worldwide, very few have been documented and this prevented us to take a formal systematic analysis. In addition, available publications for this review presented quality bias and lacked precise information such as the targeted populations (eg., first line or second line HCWs), type of program administrators (ie, volunteers, mental health professionals, nurses, doctors) informations about mental health expertise (eg., training process or not) or programs timelines. Finally, the absence of clinical outcomes descriptions does not allow to draw robust evidence and highlights the importance of waiting for the results of the two ongoing clinical trials nevertheless they seem to have stopped at the recruiting stage.

5. Conclusion

Although the limits mentioned above, this is the first review addressing this issue from a practical and descriptive prospective. It's evident the urgency to create a better connection between research and intervention programs with the goal to start from the very beginning of a new clinical program with a rigorous methodology following standards for best practice in order to be able to estimate also the effectiveness of a psychological intervention program. In the near future it will be mandatory to establish psychological treatment guidelines. Answering questions on this issue, through the analysis of rubust and replicable scientific evidence, is fundamental to advance our understanding of the most helpful services and mechanisms in order to target best practice approaches to address mental health needs of HCWs going forward. It is noteworthy that all the programs described in this review have been developed by university hospitals, so it would be interesting to evaluate whether the same programs could be developed by local communities.

Finally, all the programmes put in place so far faced resistance on the part of HCWs in admitting psychological difficulties and considering the protracted nature of the outbreak and the importance of occupational surveillance in the contest of mental health of HCWs, we believe online promotion and awareness campaigns to minimize psychological stigma should be also implemented both in the planning and execution phases of a psychological intervention program.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Anand Saha for assistance with the English language review of this article.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Albott C.S., Wozniak J.R., McGlinch B.P., Wall M.H., Gold B.S., Vinogradov S. Battle Buddies: Rapid Deployment of a Psychological Resilience Intervention for Health Care Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:43–54. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber S., Corsi M., Furukawa T.A., Cipriani A. Quality and impact of secondary information in promoting evidence-based clinical practice: a cross-sectional study about EBMH. Evid Based Ment Health. 2016;19:82–85. doi: 10.1136/eb-2016-102414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake H., Bermingham F., Johnson G., Tabner A. Mitigating the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Workers: A Digital Learning Package. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17092997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buselli R., Baldanzi S., Corsi M., Chiumiento M., Del Lupo E., Carmassi C., Dell'Osso L., Cristaudo A. Psychological Care of Health Workers during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy: Preliminary Report of an Occupational Health Department (AOUP) Responsible for Monitoring Hospital Staff Condition. Sustainability. 2020;12:5039. doi: 10.3390/su12125039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buselli R., Corsi M., Baldanzi S., Chiumiento M., Del Lupo E., Dell'Oste V., Bertelloni C.A., Massimetti G., Dell'Osso L., Cristaudo A., Carmassi C. Professional Quality of Life and Mental Health Outcomes among Health Care Workers Exposed to Sars-Cov-2 (Covid-19) Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buselli R., Carmassi C., Corsi M., Baldanzi S., Battistini G., Chiumiento M., Massimetti G., Dell'Osso L., Cristaudo A. Post-traumatic stress symptoms in an Italian cohort of subjects complaining occupational stress. CNS Spectr. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S1092852920001595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buselli R., Veltri A., Baldanzi S., Marino R., Bonotti A., Chiumiento M., Girardi M., Pellegrini L., Guglielmi G., Dell'Osso L., Cristaudo A. Plasma Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and serum cortisol levels in a sample of workers exposed to occupational stress and suffering from Adjustment Disorders. Brain Behav. 2019;9:e01298. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat J.M., Blais-Rochette C., Kokou-Kpolou C.K., Noorishad P.-G., Mukunzi J.N., McIntee S.-E., Dalexis R.D., Goulet M.-A., Labelle P.R. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat J.M., Mukunzi J.N., Noorishad P.-G., Rousseau C., Derivois D., Bukaka J. A systematic review of mental health programs among populations affected by the Ebola virus disease. J Psychosom Res. 2020;131 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.109966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Liang M., Li Y., Guo J., Fei D., Wang L., He L., Sheng C., Cai Y., Li X., Wang J., Zhang Z. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e15–e16. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sio S., Buomprisco G., La Torre G., Lapteva E., Perri R., Greco E., Mucci N., Cedrone F. The impact of COVID-19 on doctors’ well-being: results of a web survey during the lockdown in Italy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:7869–7879. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202007_22292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePierro J., Katz C.L., Marin D., Feder A., Bevilacqua L., Sharma V., Hurtado A., Ripp J., Lim S., Charney D. Mount Sinai's Center for Stress, Resilience and Personal Growth as a model for responding to the impact of COVID-19 on health care workers. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digby R., Winton-Brown T., Finlayson F., Dobson H., Bucknall T. Hospital staff well-being during the first wave of COVID-19: Staff perspectives. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020 doi: 10.1111/inm.12804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firew T., Sano E.D., Lee J.W., Flores S., Lang K., Salman K., Greene M.C., Chang B.P. Protecting the front line: a cross-sectional survey analysis of the occupational factors contributing to healthcare workers’ infection and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godderis L., Boone A., Bakusic J. COVID-19: a new work-related disease threatening healthcare workers. Occup Med (Lond) 2020;70:315–316. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E.A., O'Connor R.C., Perry V.H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L., Ballard C., Christensen H., Cohen Silver R., Everall I., Ford T., John A., Kabir T., King K., Madan I., Michie S., Przybylski A.K., Shafran R., Sweeney A., Worthman C.M., Yardley L., Cowan K., Cope C., Hotopf M., Bullmore E. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Zhuang D., Xiong B., Deng D.X., Li H., Lai W. Occupational exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in burns treatment during the COVID-19 epidemic: Specific diagnosis and treatment protocol. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y.-H., Huang Q., Wang Y.-Y., Zeng X.-T., Luo L.-S., Pan Z.-Y., Yuan Y.-F., Chen Z.-M., Cheng Z.-S., Huang X., Wang N., Li B.-H., Zi H., Zhao M.-J., Ma L.-L., Deng T., Wang Y., Wang X.-H. Perceived infection transmission routes, infection control practices, psychosocial changes, and management of COVID-19 infected healthcare workers in a tertiary acute care hospital in Wuhan: a cross-sectional survey. Mil Med Res. 2020;7:24. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00254-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy Y., Nagarajan R., Saya G.K., Menon V. Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research. 2020;293 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., Cai Z., Hu J., Wei N., Wu J., Du H., Chen T., Li R., Tan H., Kang L., Yao L., Huang M., Wang H., Wang G., Liu Z., Hu S. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefèvre H., Stheneur C., Cardin C., Fourcade L., Fourmaux C., Tordjman E., Touati M., Voisard F., Minassian S., Chaste P., Moro M.R., Lachal J. The Bulle: Support and Prevention of Psychological Decompensation of Health Care Workers During the Trauma of the COVID-19 Epidemic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiorano T., Vagni M., Giostra V., Pajardi D. COVID-19: Risk Factors and Protective Role of Resilience and Coping Strategies for Emergency Stress and Secondary Trauma in Medical Staff and Emergency Workers—An Online-Based Inquiry. Sustainability. 2020;12:9004. doi: 10.3390/su12219004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marine A., Ruotsalainen J., Serra C., Verbeek J. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002892.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins C.A., Mayer L.E.S., Glasofer D.R., Devlin M.J., Albano A.M., Nash S.S., Engle E., Cullen C., Ng W.Y.K., Allmann A.E., Fitelson E.M., Vieira A., Remien R.H., Malone P., Wainberg M.L., Baptista-Neto L. Supporting the well-being of health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The CopeColumbia response. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;67:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morina, N., 2020. RECHARGE: A Brief Psychological Intervention to Build Resilience in Healthcare Workers During COVID-19 (Clinical trial registration No. NCT04531774). clinicaltrials.gov.

- Muller A.E., Hafstad E.V., Himmels J.P.W., Smedslund G., Flottorp S., Stensland S.Ø., Stroobants S., Van de Velde S., Vist G.E. The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: A rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Research. 2020;293 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L.H., Drew D.A., Graham M.S., Joshi A.D., Guo C.-G., Ma W., Mehta R.S., Warner E.T., Sikavi D.R., Lo C.-H., Kwon S., Song M., Mucci L.A., Stampfer M.J., Willett W.C., Eliassen A.H., Hart J.E., Chavarro J.E., Rich-Edwards J.W., Davies R., Capdevila J., Lee K.A., Lochlainn M.N., Varsavsky T., Sudre C.H., Cardoso M.J., Wolf J., Spector T.D., Ourselin S., Steves C.J., Chan A.T. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e475–e483. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini A., Corsi M., Santangelo A., Riva A., Peroni D., Foiadelli T., Savasta S., Striano P. Challenges and management of neurological and psychiatric manifestations in SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) patients. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:2353–2366. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04544-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., Giannakoulis V.G., Papoutsi E., Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R.S., Bachu R., Adikey A., Malik M., Shah M. Factors Related to Physician Burnout and Its Consequences: A Review. Behav Sci (Basel) 2018;8 doi: 10.3390/bs8110098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:510–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock A., Campbell P., Cheyne J., Cowie J., Davis B., McCallum J., McGill K., Elders A., Hagen S., McClurg D., Torrens C., Maxwell M. Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: a mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaci T., Barattucci M., Ledda C., Rapisarda V. Social Stigma during COVID-19 and its Impact on HCWs Outcomes. Sustainability. 2020;12:3834. doi: 10.3390/su12093834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruotsalainen J., Serra C., Marine A., Verbeek J. Systematic review of interventions for reducing occupational stress in health care workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2008;34:169–178. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaan (Zena), Z., 2020. The Role of Virtual Peer Support Platforms for Reducing Stress and Burnout Among Frontline Healthcare Workers During COVID-19: A Randomized Controlled Trial (Clinical trial registration No. NCT04474080). clinicaltrials.gov.

- Schwartz R., Sinskey J.L., Anand U., Margolis R.D. Addressing Postpandemic Clinician Mental Health : A Narrative Review and Conceptual Framework. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt T., Ripp J., Trockel M. Understanding and Addressing Sources of Anxiety Among Health Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323:2133–2134. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K., Ostinelli E., Macdonald O., Cipriani A. COVID-19 and Telepsychiatry: Development of Evidence-Based Guidance for Clinicians. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7:e21108. doi: 10.2196/21108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman A.H., Ahmad Sabki Z., Jaafa M.J., Francis B., Razali K.A., Juares Rizal A., Mokhtar N.H., Juhari J.A., Zainal S., Ng C.G. Development of a Remote Psychological First Aid Protocol for Healthcare Workers Following the COVID-19 Pandemic in a University Teaching Hospital. Malaysia. Healthcare (Basel) 2020;8 doi: 10.3390/healthcare8030228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B.Y.Q., Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., Jing M., Goh Y., Yeo L.L.L., Zhang K., Chin H.-K., Ahmad A., Khan F.A., Shanmugam G.N., Chan B.P.L., Sunny S., Chandra B., Ong J.J.Y., Paliwal P.R., Wong L.Y.H., Sagayanathan R., Chen J.T., Ng A.Y.Y., Teoh H.L., Ho C.S., Ho R.C., Sharma V.K. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:317–320. doi: 10.7326/M20-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troyer E.A., Kohn J.N., Hong S. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trumello C., Bramanti S.M., Ballarotto G., Candelori C., Cerniglia L., Cimino S., Crudele M., Lombardi L., Pignataro S., Viceconti M.L., Babore A. Psychological Adjustment of Healthcare Workers in Italy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Differences in Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Burnout, Secondary Trauma, and Compassion Satisfaction between Frontline and Non-Frontline Professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17:8358. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagni M., Maiorano T., Giostra V., Pajardi D. Hardiness, Stress and Secondary Trauma in Italian Healthcare and Emergency Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2020;12:5592. doi: 10.3390/su12145592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walton M., Murray E., Christian M.D. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Heart Journal: Acute Cardiovascular Care. 2020;9:241–247. doi: 10.1177/2048872620922795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Zhao X., Feng Q., Liu L., Yao Y., Shi J. Psychological assistance during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. J Health Psychol. 2020;25:733–737. doi: 10.1177/1359105320919177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman S., Hunter E.C.M., Cole C.L., Evans L.J., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J., Beck A. Training peers to treat Ebola centre workers with anxiety and depression in Sierra Leone. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64:156–165. doi: 10.1177/0020764017752021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Health Worker Occupational Health [WWW Document], 2021 n.d. URL https://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/hcworkers/en/ (accessed 11.17.20).

- WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard | WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://covid19.who.int/(accessed 15.02.21).

- Zaka A., Shamloo S.E., Fiorente P., Tafuri A. COVID-19 pandemic as a watershed moment: A call for systematic psychological health care for frontline medical staff. J Health Psychol. 2020;25:883–887. doi: 10.1177/1359105320925148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]