To the editor:

Common variable immune deficiency (CVID) is a primary antibody deficiency characterized by a marked decrease of immunoglobulin (Ig) G in combination with low IgA and/or IgM, an impaired response to immunization and recurrent infections [1]. Up to 68% of CVID patients have additional noninfectious complications (NIC), including autoimmune complications, malignancies, and granulomatous disease. These NIC are associated with increased morbidity and mortality [2–4]. Granulomatous disease, especially granulomatous and lymphocytic interstitial lung disease (GLILD), leads to a significant reduction in median survival in CVID patients [5]. Granuloma formation is thought to be initiated by CD4+ T lymphocytes that become activated after interaction with antigen presenting cells [6]. Activated CD4+ T lymphocytes secrete cytokines that subsequently stimulate macrophage activation and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α production, ultimately leading to the characteristic immune cell agglomerates (i.e., granulomas) in various organs.

Several studies have tried to identify potential biomarkers for NIC in CVID. It has been shown that increased numbers of PD-1 high CCR7 low CD4+ T follicular-helper-lymphocytes are associated with autoimmune complications or granulomatous disease [7]. Furthermore, an association between elevated serum IgM and interstitial lung disease in CVID, which was related to B cell follicles within the lung parenchyma, is reported [8]. In pediatric CVID patients, it was observed that reduction in total B and NK lymphocytes with an increase in CD8+ T lymphocytes was associated with presence of bronchiectasis [9]. Hartono et al. [10] described a prediction model for the presence of GLILD in CVID. They showed that a medical history of splenomegaly, immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) and/or autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), IgA levels < 13 mg/dl, and CD21-low B lymphocytes > 5% of total CD21 B cells are to be predictive measures for GLILD in CVID [10]. We were interested to see whether these clinical and immunological features were also predictive for GLILD in our CVID cohort. Therefore, we collected data on the presence of splenomegaly, ITP, AIHA, the IgA levels, and the frequency of CD21-low B lymphocytes from our cohort of CVID patients, which resulted in a subgroup of 38 CVID patients of which all these characteristics were available. In our cohort, only the presence of splenomegaly was found to be significantly increased in patients with GLILD when compared to CVID patients without GLILD. Moreover, also in patients with granulomatous complications affecting other organ systems, including spleen and lymph nodes, only splenomegaly positively correlated with the presence of granulomatous disease (Supplementary Table 1). However, it has to be taken into account that sample sizes used for analysis were small.

These findings prompted us to search for a low-invasive biomarker to diagnose and monitor the progression of granulomatous disease in CVID. The soluble form of the interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R or sCD25), which is secreted by activated T lymphocytes, is frequently used to monitor immune cell activation. Elevated sIL-2R levels have been reported in various pathological conditions, including autoimmune diseases, infection, and malignancies [11–14]. Previous studies showed that sIL-2R levels in CVID patients in general are higher than in healthy controls (HCs) [15–17]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that sIL-2R levels are higher in CVID patients with NIC when compared to patients with infections-only (IO), or CVID patients with gastrointestinal symptoms [18, 19]. Furthermore, a decline of sIL-2R was found to coincide with clinical improvement after abatacept treatment in patients with CTLA-4 haploinsufficiency and lipopolysaccharide responsive beige-like anchor protein (LRBA)-deficiency [7, 20, 21].

The relation between sIL-2R level and granulomatous disease in CVID patients has not been extensively studied. Only one case study described a decline of serum sIL-2R in a CVID patient with granulomatous lung diseases after effective immunosuppressive therapy with azathioprine and rituximab [22]. In sarcoidosis, an inflammatory multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology, serum sIL-2R, was reported as a sensitive biomarker [23, 24]. Therefore, we aimed to determine whether serum sIL-2R level can be used as a low-invasive biomarker for detection of granulomatous disease and for monitoring granuloma progression or remission in CVID patients.

To this aim we performed a retrospective single-center analysis, evaluating serum sIL-2R levels in 48 CVID patients, including 12 patients with granulomatous disease, 13 healthy controls (HC), and 79 sarcoidosis patients previously reported by our group (Supplemental Table 2 and the method section in the supplemental data) [23]. Similar to the previous studies, the CVID group displayed significantly higher sIL-2R levels (median sIL-2R 4,539 pg/ml; range: 1,037–48,875 pg/ml) compared to the HC group (median sIL-2R 1,419 pg/ml; range: 1,096–3,328 pg/ml) (Supplemental Fig. 1a, Supplemental Table 2) [15, 17, 18]. The variability of sIL-2R levels observed within the CVID group was not related to the type of immunoglobulin replacement therapy, since no significant difference was observed in sIL-2R levels across the various treatment modalities (Supplemental Fig. 1b). Interestingly, the group of CVID patients with NIC (CVID+NIC, n = 22) had significantly higher sIL-2R levels (median: 6,612 pg/ml; range: 1,620–48,875 pg/ml) than the CVID group with IO (CVID IO; n = 26; median sIL-2R: 2,918 pg/ml; range: 1,037–17,300 pg/ml) or HC (Supplemental Fig. 1c, Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). This is in line with a previous study that showed significantly higher sIL-2R levels in CVID patients with NIC, compared to CVID patients with infections only or HC [18].

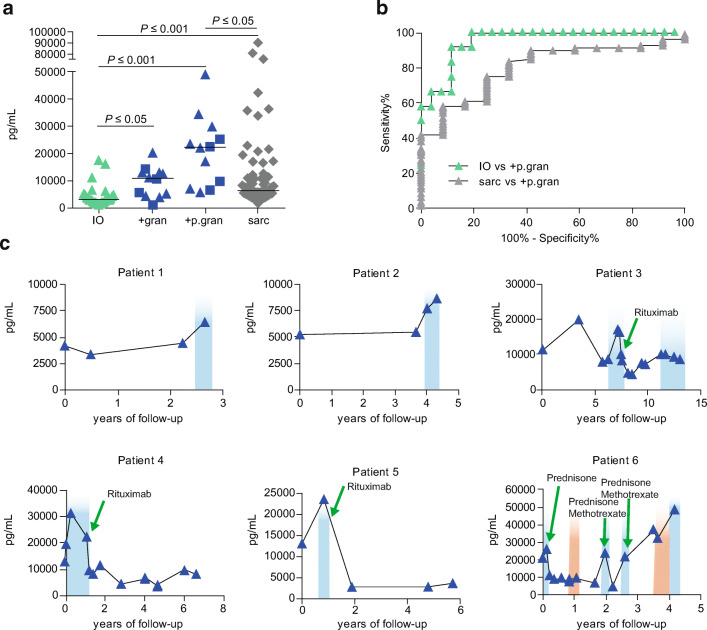

To determine whether CVID patients with granulomatous disease have increased levels of sIL-2R, we compared sIL-2R levels prior to and at the time when there was reported progression of granulomatous disease (CVID+p.granuloma) with CVID patients with IO. Data on progression of granulomatous disease were derived from clinical reports, computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or pathology reports from patient files. Interestingly, the CVID+granuloma group (median sIL-2R: 10,853 pg/ml; range: 4,458–13,049 pg/ml) displayed significantly higher serum sIL-2R levels than CVID IO (Fig. 1a). Moreover, sIL-2R levels increased upon progression of granulomatous disease (CVID+p.granuloma, median sIL-2R: 22,274 pg/ml; range: 5,476–48,875 pg/ml) (Fig. 1a). Also, median levels of sIL-2R in both CVID+granuloma and CVID+p.granuloma were higher than the median levels we previously measured in sarcoidosis patients (n = 79; median sIL-2R: 6,000 pg/ml; range: 1,600–90,300 pg/ml), only reaching statistical significance for CVID+p.granuloma (Fig. 1a, Supplemental Table 2) [23].

Fig. 1.

Discriminative capacity of serum sIL-2R. a sIL-2R levels per subgroups of CVID (CVID IO (IO, n = 26); CVID+granuloma (+gran, n = 12); CVID+progression of granulomatous disease (+p.gran, n = 12) and sarcoidosis (sarc, n = 79). b ROC-curves showing discriminating capacity of sIL-2R. Black lines indicate median, square symbols are CVID patients with multiple NIC. c Longitudinal sIL-2R analysis of 6 CVID+granuloma patients. sIL-2R levels are showed per years after start sampling (first time point) of sIL-2R. Blue gradient indicates progression of granulomatous disease derived from patient files. Green arrows shown in patient 3 until 6 indicate start of antigranuloma treatment. The red gradient indicate episodes of collagen colitis in patient 6

To further determine whether serum sIL-2R could be used to differentiate between CVID patients with progression of granulomatous complications and other CVID patients, a Receiver Operator Curve (ROC) analysis was performed (Fig. 1b, Supplemental Fig. 1d). This revealed that serum sIL-2R can be used to differentiate between CVID+p.granuloma and CVID IO (area under the curve (AUC) = 0.95) (Fig. 1b, Supplemental Table 4). Using a cutoff value for sIL-2R of > 6,376 pg/ml, yielded a high sensitivity of 91.7% and a high specificity of 88.5% with a Youden’s Index (YI) of 0.80 to differentiate between CVID+p.granuloma and CVID IO. These findings suggest that high sIL-2R level (> 6,376 pg/ml) might represent a clinically valuable biomarker to differentiate CVID patients with granulomatous complications from other CVID patients.

The clinical context of the patient of which serum sIL-2R level is measured and interpreted is important, since sIL-2R is increased in many inflammatory diseases or complications [14]. Therefore, the sensitivity is predicted to be high, while specificity is low. To evaluate whether an increase of sIL-2R levels was associated with other inflammatory complications, clinical profiles of the included patients were studied, focusing on additional inflammatory complications, including presence of bronchiectasis, ground glass lesions, lymphoproliferation, splenomegaly, and intestinal complications, at time of serum sampling. No association was observed between other inflammatory complications and sIL-2R levels (Supplemental Table 3).

Although overlap existed in sIL-2R levels between sarcoidosis and CVID+p.gran, in general, sIL-2R levels in sarcoidosis were lower (median 6,000 pg/ml) than in CVID+p.gran (median 22,274 pg/ml) (Supplementary Table 2). We observed that serum sIL-2R could differentiate between CVID+p.granuloma and sarcoidosis with a sensitivity of 91.1%, specificity of 41.7% and YI from 0.33 using a cutoff value of < 23,223 pg/ml. This indicated that sIL-2R levels lower than 23,223 pg/ml are associated with lower probability of having granulomatous disease progression in CVID, but rather may be indicative for sarcoidosis, a granulomatous disease CVID patients can be misdiagnosed with. Therefore, additional diagnostics such as serum immunoglobulin levels should be performed to rule out the diagnosis of sarcoidosis [25].

Since we observed increasing sIL-2R levels upon progression of granulomatous disease (Fig. 1a), we further analyzed longitudinal serum sIL-2R measurements of six CVID patients with granulomatous disease of which longitudinal data were available. Interestingly, sIL-2R levels increased in all patients when progression of granulomatous disease was clinically observed (Fig. 1c). Moreover, a decrease in sIL-2R levels was observed after effective treatment with rituximab, prednisone, or prednisone in combination with methotrexate (Fig. 1c). This further strengthens the previous notion that serum sIL-2R can be used to monitor the effect of treatment for granulomatous disease in CVID [22]. In patient 6, the sIL-2R levels also increased during a second episode of collagen colitis, which supports the previous findings of increased sIL-2R levels in patient with gastrointestinal symptoms [19].

Of note, the baseline levels of sIL-2R levels were different for each CVID patient. This suggests that it is important to regularly monitor sIL-2R levels in order to timely detect an increase in serum sIL-2R relative to the patient baseline sIL-2R level. Although sIL-2R is related to many immune-regulated processes, an increase could reflect development or progression of granulomatous disease.

In summary, our data indicate that in patients with CVID sIL-2R levels rise with progression of granulomatous disease. On the other hand, sIL2R levels decline upon remission of granulomatous disease after treatment. These observations suggest that sIL-2R levels can be used as monitoring tool for evaluation of progression and treatment efficacy of granulomatous disease in CVID.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 291 kb)

Acknowledgments

The research for this manuscript was performed within the framework of the Erasmus Postgraduate School Molecular Medicine. The authors would like to express their gratitude especially to P.M. Kolijn, for his help with the statistical analysis and R scripts and M.W. van der Ent for her valuable help retrieving patient information.

Author’s Contribution

VD, HIJ, and WD designed study. NN and DR performed experiments. AS analyzed the data. BB, VD, PH, and AS collected clinical data. AS, VD, HIJ, and WD wrote manuscript. All authors critically red the manuscript and provided feedback.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hanna IJspeert and Willem A. Dik contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Seidel MG, Kindle G, Gathmann B, Quinti I, Buckland M, van Montfrans J, Scheible R, Rusch S, Gasteiger LM, Grimbacher B, Mahlaoui N, Ehl S, Abinun M, Albert M, Cohen SB, Bustamante J, Cant A, Casanova JL, Chapel H, de Saint Basile G, de Vries E, Dokal I, Donadieu J, Durandy A, Edgar D, Espanol T, Etzioni A, Fischer A, Gaspar B, Gatti R, Gennery A, Grigoriadou S, Holland S, Janka G, Kanariou M, Klein C, Lachmann H, Lilic D, Manson A, Martinez N, Meyts I, Moes N, Moshous D, Neven B, Ochs H, Picard C, Renner E, Rieux-Laucat F, Seger R, Soresina A, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Thon V, Thrasher A, van de Veerdonk F, Villa A, Weemaes C, Warnatz K, Wolska B, Zhang SY. The European Society for Immunodeficiencies (ESID) registry working definitions for the clinical diagnosis of inborn errors of immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:1763–1770. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnick ES, Moshier EL, Godbold JH, Cunningham-Rundles C. Morbidity and mortality in common variable immune deficiency over 4 decades. Blood. 2012;119(7):1650–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapel H, Cunningham-Rundles C. Update in understanding common variable immunodeficiency disorders (CVIDs) and the management of patients with these conditions. Br J Haematol. 2009;145(6):709–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho HE, Cunningham-Rundles C. Non-infectious complications of common variable immunodeficiency: updated clinical spectrum, sequelae, and insights to pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 2020;11:149. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bates CA, Ellison MC, Lynch DA, Cool CD, Brown KK, Routes JM. Granulomatous-lymphocytic lung disease shortens survival in common variable immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(2):415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Co DO, Hogan LH, Il-Kim S, Sandor M. T cell contributions to the different phases of granuloma formation. Immunol Lett. 2004;92(1–2):135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coraglia A, et al. Common variable immunodeficiency and circulating TFH. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:4951587. doi: 10.1155/2016/4951587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maglione PJ, Gyimesi G, Cols M, Radigan L, Ko HM, Weinberger T, Lee BH, Grasset EK, Rahman AH, Cerutti A, Cunningham-Rundles C. BAFF-driven B cell hyperplasia underlies lung disease in common variable immunodeficiency. JCI Insight. 2019;4(5):e122728. 10.1172/jci.insight.122728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Ogulur I, Kiykim A, Baser D, Karakoc-Aydiner E, Ozen A, Baris S. Lymphocyte subset abnormalities in pediatric-onset common variable immunodeficiency. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2020;181(3):228–237. doi: 10.1159/000504598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartono S, Motosue MS, Khan S, Rodriguez V, Iyer VN, Divekar R, Joshi AY. Predictors of granulomatous lymphocytic interstitial lung disease in common variable immunodeficiency. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118(5):614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caruso C, Candore G, Cigna D, Colucci AT, Modica MA. Biological significance of soluble IL-2 receptor. Mediat Inflamm. 1993;2(1):3–21. doi: 10.1155/S0962935193000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witkowska AM. On the role of sIL-2R measurements in rheumatoid arthritis and cancers. Mediat Inflamm. 2005;2005(3):121–130. doi: 10.1155/MI.2005.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Co DO, Hogan LH, Kim SI, Sandor M. Mycobacterial granulomas: keys to a long-lasting host-pathogen relationship. Clin Immunol. 2004;113(2):130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dik WA, Heron M. Clinical significance of soluble interleukin-2 receptor measurement in immune-mediated diseases. Neth J Med. 2020;78(5):220–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hel Z, Huijbregts RPH, Xu J, Nechvatalova J, Vlkova M, Litzman J. Altered serum cytokine signature in common variable immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2014;34(8):971–8. doi: 10.1007/s10875-014-0099-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Litzman J, Nechvatalova J, Xu J, Ticha O, Vlkova M, Hel Z. Chronic immune activation in common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is associated with elevated serum levels of soluble CD14 and CD25 but not endotoxaemia. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;170(3):321–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.North ME, Spickett GP, Webster AD, Farrant J. Raised serum levels of CD8, CD25 and beta 2-microglobulin in common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;86(2):252–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jorgensen SF, et al. Altered gut microbiota profile in common variable immunodeficiency associates with levels of lipopolysaccharide and markers of systemic immune activation. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9(6):1455–1465. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jorgensen SF, et al. A cross-sectional study of the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms and pathology in patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(10):1467–1475. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo B, Zhang K, Lu W, Zheng L, Zhang Q, Kanellopoulou C, Zhang Y, Liu Z, Fritz JM, Marsh R, Husami A, Kissell D, Nortman S, Chaturvedi V, Haines H, Young LR, Mo J, Filipovich AH, Bleesing JJ, Mustillo P, Stephens M, Rueda CM, Chougnet CA, Hoebe K, McElwee J, Hughes JD, Karakoc-Aydiner E, Matthews HF, Price S, Su HC, Rao VK, Lenardo MJ, Jordan MB. Autoimmune disease. Patients with LRBA deficiency show CTLA4 loss and immune dysregulation responsive to abatacept therapy. Science. 2015;349(6246):436–440. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alroqi FJ, Charbonnier LM, Baris S, Kiykim A, Chou J, Platt CD, Algassim A, Keles S, al Saud BK, Alkuraya FS, Jordan M, Geha RS, Chatila TA. Exaggerated follicular helper T-cell responses in patients with LRBA deficiency caused by failure of CTLA4-mediated regulation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(3):1050–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vitale J, Convers KD, Goretzke S, Guzman M, Noyes B, Parkar N, Knutsen AP. Serum IL-12 and soluble IL-2 receptor levels as possible biomarkers of granulomatous and lymphocytic interstitial lung disease in common variable immunodeficiency: a case report. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(2):273–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eurelings LEM, Miedema JR, Dalm VASH, van Daele PLA, van Hagen PM, van Laar JAM, Dik WA. Sensitivity and specificity of serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor for diagnosing sarcoidosis in a population of patients suspected of sarcoidosis. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vorselaars AD, et al. ACE and sIL-2R correlate with lung function improvement in sarcoidosis during methotrexate therapy. Respir Med. 2015;109(2):279–285. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verbsky JW, Routes JM. Sarcoidosis and common variable immunodeficiency: similarities and differences. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(3):330–335. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1376862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 291 kb)