Abstract

Objectives

Heart transplantation is the gold standard of treatments for end-stage heart failure, but its use is limited by extreme shortage of donor organs. The time “window” between procurement and transplantation sets the stage for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (I/R), which constrains the maximal storage time and lowers utilization of donor organs. Given mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived paracrine protection, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy of MSC-conditioned medium (MSC-CM) and extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) when added to ex-vivo preservation solution on ameliorating I/R-induced myocardial damage in donor hearts.

Methods

Mouse donor hearts were stored at 0–4°C of <1hr-cold ischemia (<1hr-I), 6hr-I + vehicle, 6hr-I + MSC-CM, 6hr-I + MSC-EVs, and 6hr-I + MSC-CM from MSCs treated with exosome release inhibitor. The hearts were then heterotopically implanted into recipient mice. At 24-hour post-surgery, myocardial function was evaluated. Heart tissue was collected for analysis of histology, apoptotic cell death, microRNA (miR)-199a-3p expression, and myocardial cytokine production.

Results

6hr-cold ischemia significantly impaired myocardial function, increased cell death, and reduced miR-199a-3p in implanted hearts vs. <1hr-I. MSC-CM or MSC-EVs in preservation solution reversed detrimental effects of prolong cold ischemia on donor hearts. Exosome-depleted MSC-CM partially abolished MSC secretome-mediated cardioprotection in implanted hearts. MiR-199a-3p was highly enriched in MSC-EVs. MSC-CM and MSC-EVs increased cold ischemia-downregulated miR-199a-3p in donor hearts, whereas exosome-depletion neutralized this effect.

Conclusions

MSC-CM and MSC-EVs confer improved myocardial preservation in donor hearts during prolonged cold static storage and MSC-EVs can be used for intercellular transport of miRNAs in heart transplantation.

Keywords: murine heterotopic heart transplantation, stem cell secretome, extracellular vesicles, microRNA, myocardial ischemia reperfusion, graft function

Introduction

Heart transplantation is the effective treatment for end-stage heart failure, but its use is limited by extreme shortage of donor organs. Due to the insufficient number of suitable donor hearts, more than a third of patients are either permanently removed from waiting lists or die before receiving transplants 1. Therefore, it is critical to increasing the number of suitable donor hearts for transplantation. Currently, cold static storage remains the gold standard for organ preservation. However, it is associated with cold ischemia, the prolongation of which is an independent risk factor for primary graft failure and recipient death after transplantation 2, 3, thus limiting the maximal storage time to 4–6 hours 4. Generally, the ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury progressively deteriorates graft and patient outcomes beyond this time. Modification of organ preservation solution to prolong the time for ex-vivo preservation of donor hearts is appealing. Particularly, this affects potential recipients in distant geographical areas.

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-based therapy represents one of promising approaches for treatment of ischemic tissues/organs. Accumulating studies from clinical trials have revealed its safety and practicality, as well as the potential effectiveness in treating ischemic heart disease 5–8. Compelling evidence from others and our group has demonstrated that MSC paracrine action is the primary mechanism to mediate tissue protection from ischemia 9–16. We have shown that pretreatment with human MSCs acutely improve myocardial functional recovery following I/R injury 10. We have also demonstrated that using MSCs significantly protects myocardium from the ischemic injury in both in-vivo and ex-vivo study 9. Of note, emerging evidence has suggested MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exo) could emulate MSC secretome-mediated cardiac protection 17 . Surprisingly, no study has reported using MSC secretome, particularly exosomes, to reduce ischemic injury in donor hearts during preservation. Accordingly, we are the first to evaluate the MSC conditioned medium (CM) and their exosomes as an adjunct to standard preservation solution on ameliorating cold ischemia-induced damage in donor organs during ex-vivo storage by using an in-vivo murine cervical heterotopic heart transplantation model.

Methods and Materials

Animals

Adult (12–16 weeks) male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories and acclimated for > 5 days before experiments. The animal protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Indiana University. All animals received humane care in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Pub. No. 85–23, revised 1996).

Preparation of human MSC-CM and MSC-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs)

Human MSCs were harvested from healthy male human bone marrow and purchased from the Lonza Inc. (PT-2501). The cells were cultured with MSC basal medium + MSC growth bulletkit (Lonza) based on the manufacturer’s instructions and our previous experience 13. The medium was changed every 3 days. CM was generated as shown in Figure S1A. After 72hr-cultivation, the medium was collected and centrifuged at 3000g for 15 minutes. The supernatant was then sequentially concentrated to 100-fold by centrifugation through the Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter (membranes cutoff >3 kDa, EMD Millipore) as we previously described 18. The concentrated CM from the filtrate tube of the top unit was diluted in University of Wisconsin (UW) solution to the final concentration as indicated in Figure S1A. The MSC-CM from the centrifuge tube of the bottom unit that did not contain soluble factors >3 kDa and EVs was used as conditioned media control (cMC).

EVs were isolated from the concentrated MSC-CM using ExoQuick-TC exosome isolation kit (System Biosciences) (Fig. S1A). EV pellets were re-suspended with PBS and stored at −80°C. The morphology of exosomes was determined by transmission electron microscope (TEM). Size distribution of EVs was measured by Nanosight analysis.

The MSC-CM was further collected from MSCs treated with 10 μM GW4869 (an exosome release inhibitor) for 72hr 19 to investigate the therapeutic effect of exosome-depleted MSC-CM (Fig. S1B).

Murine Cervical Heterotopic Heart Transplantation

After C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized and heparinized, donor hearts were flushed with 1ml of cold UW containing vehicle, MSC-CM, or MSC-EVs via the ascending aorta. After excision, these hearts were stored in the same solution at 0–4°C. After storage, donor hearts were heterotopically implanted into male syngeneic C57BL/6 recipients 20. Briefly, recipient mouse was anesthetized with isoflurane and placed in a supine position on a warm (37°C) pad under an operating microscope. A skin incision was made from the jugular notch to the right lower mandible. The right lobe of the submandibular gland was removed to provide the space for placing donor heart. The right external jugular vein and the common carotid artery were mobilized and divided. The cuff was passed through these vessels, respectively. The vessels of donor heart were connected to the recipient as follows: donor pulmonary artery to recipient right external jugular vein and donor aorta to recipient common carotid artery. The surgical procedure for these anastomoses between the graft and the recipient was shown in video 1. After removing the clamp on the right external jugular vein and the carotid artery, the implanted heart was filled with blood instantly and started beating within two minutes. After the implanted heart beating normally, the skin was closed. At 24 hours post-implantation, myocardial function (left ventricular developed pressure [LVDP], heart rate, and +/− dP/dT) was detected in transplanted hearts using a Millar Mikro-Tip pressure catheter (SPR-671, Millar Inc.) that was inserted into the LV of the implanted heart in recipient animals under isoflurane anesthesia. Data were recorded using a PowerLab 8 data acquisition digitizer (ADInstruments Inc.). The pulse pressure difference was measured by inserting Millar pressure catheter into abdominal aorta of recipient mice. Native and donor heart rates were also recorded by electrocardiogram (ECG).

A total of 54 donor hearts were randomly divided into groups of: 1) <1hr-cold storage as baseline control (<1hr-I); 2) 6hr-I + basal medium without cell cultivation (6hr-I + vehicle); 3) 6hr-I + MSC-CM (6hr-I + CM); 4) 6hr-I + MSC-EVs; and 5) 6hr-I + MSC-CMGM4869. Within 24 hours, seven recipients (13%) were dead or experienced with a non-beating implanted heart due to twisted anastomosis vessels and/or thrombosis. These animals were excluded from further analysis. At 24 hours post-implantation, the remaining recipient mice were euthanized for harvesting donor hearts.

Histological Analysis

After grafts were collected, a portion (cross-section) of heart tissue was fixed in 10% buffered formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and then sectioned for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The graft damage was determined in H&E-stained sections in a blinded-fashion by scientists of the Pathology & Laboratory Medicine.

Apoptotic Cell Death ELISA

Cytoplasmic fraction in equal amount was prepared from mouse donor hearts 24-hour post implantation and was used to detect cell death using a commercially available Cell Death Detection ELISA kit (Roche Applied Science). Cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragments were determined in duplicates of the samples and ELISA was conducted based on the manufacturer’s instruction.

Transmission electron microscope

The morphology of exosomes was determined by TEM. Isolated EVs were fixed with 4% formaldehyde. Three hundred mesh grids were placed under the sample and allowed to absorb overnight at 4°C. The grids were then dried and stained with Nanovan. The grids were viewed with images taken by a CCD camera.

Western Blotting

EVs, MSCs and MSC-CM were lysed by RIPA buffer containing Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (ThermoFisher Scientific). The protein extracts were electrophoresed and the gel was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The primary antibodies against CD63 (System Biosciences), Flotillin1 and GM130 (Cell Signaling Technology), and goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody were employed. The images were detected by GE CCD camera-based imager.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from donor mouse hearts, MSCs, and MSC-EVs using miRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). 20 ng of total RNA from each preparation was used for the first-strand cDNA reverse transcription using TaqMan microRNA reverse transcription kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) with primers of U6 snRNA (NR_004394, TaqMan microRNA control assay), microRNA (miR)-199a-3p (002304), and miR-199a-5p (000498). We selected to study miR-199a family because miR-199a-3p was identified as one of the most altered miRNAs in 6hr-I + adipose tissue-derived MSC-CM mouse hearts (Fig. S2). Transcript levels were then determined by Real-time PCR (Light Cycler 96, Roche) using U6 snRNA TaqMan miR control assay and TaqMan miR-199a-3p assay (ThermoFisher Scientific). The expression of miR-199a-3p and miR-199a-5p was normalized to U6 snRNA levels using the standard 2−ΔCT methods.

Cytokine ELISA

Donor hearts from 24-hour post-transplantation were homogenized in cold RIPA buffer. Supernatant was utilized for analyzing protein levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α by ELISA (DY401 [IL-1β], DY406 [IL-6], and DY410 [TNF-α]; R&D Systems Inc.) based on the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples and standards were measured in duplicate.

Proteome Profiler Mouse Cytokine Array

A membrane-based antibody array (ARY006, R&D Systems Inc.) was utilized to detect 40 cytokines and chemokines according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal protein amount (100 μg/sample) of four samples from each group (6hr-I, 6hr-I+MSC-CM, and 6hr-I+MSC-EVs) was pooled for the array. The signal densities were analyzed using the ImageJ.

Statistical Analysis

The reported results are shown as box-and-whiskers plots with each dot for individual measurement. The primary outcomes are cardiac function, including LVDP, +/− dP/dt, rate pressure product (RPP), and heart rate. Data were checked for variables using Shapiro-Wilk normality test and then analyzed using either one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis or t-test. Three data sets not passed for normality test were evaluated using either Kruskal-Wallis test or Mann Whitney test. Difference was considered statistically significant when p <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism software.

Results

Six-hour cold ischemia delayed recovery of donor hearts and impaired myocardial function

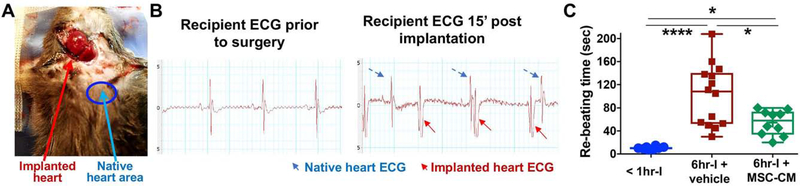

Fig. 1A and 1B show a mouse containing two beating hearts with two distinct QRS complex morphologies. Notably, the implanted hearts in 6hr-I groups took longer time to resume their spontaneous sinus rhythm (re-beating time) compared to those hearts in <1hr-I group (Fig. 1C), implying that the longer storage time, the more delayed recovery donor hearts encountered. However, adding MSC-CM to UW solution significantly improved donor heart recovery, as demonstrated by decreased re-beating time in these hearts.

Figure 1.

The cervical heterotopic heart transplantation. A. Donor hearts from C57BL/6 male mice were implanted into C57BL/6 male recipient mice. The cervical skin was closed after the implanted heart was observed to resume normal sinus rhythm. B. The ECG indicated two distinct QRS complex morphologies: the graft vs. native heart post transplantation. C. Re-beating time (the time for implanted donor hearts to resume their spontaneous sinus rhythm after transplantation) among groups of < 1hr-cold ischemia (I), 6hr-I + vehicle and 6hr-I + MSC-CM (mesenchymal stem cell conditioned media). There was longer time for returning spontaneous sinus rhythm in the implanted hearts of the 6hr-I group compared to those hearts in <1hr-I group. Adding MSC-CM to UW (University of Wisconsin) solution markedly shortened the time to resume sinus rhythm in these donor heart at the reperfusion. *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001. The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal line represents the median; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum values. Dots represent individual measurements.

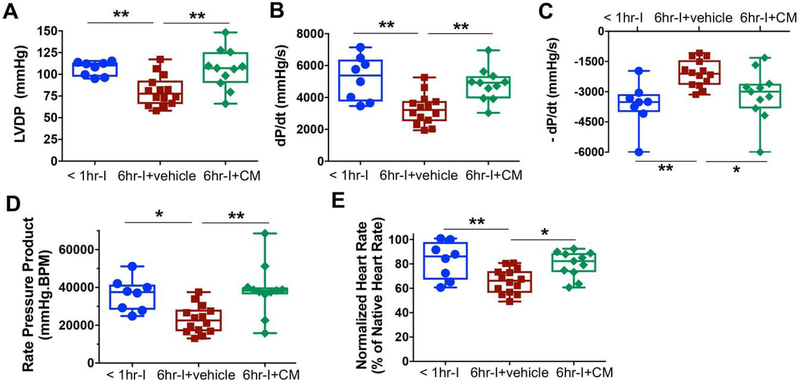

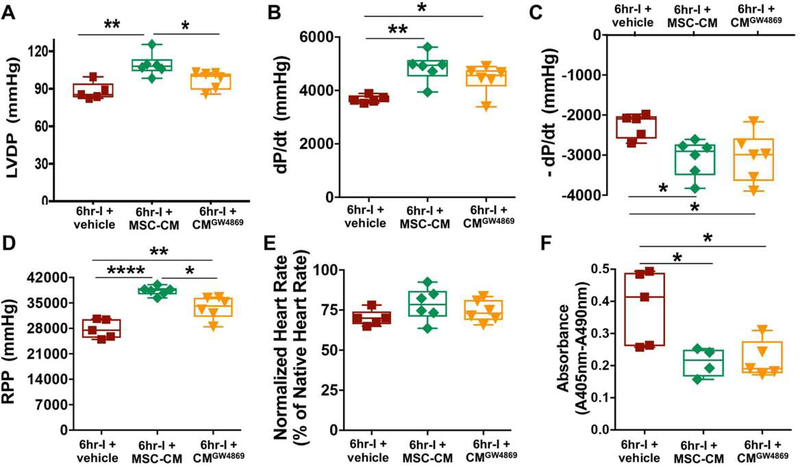

Ventricular dysfunction within the first 24 hours of heart transplantation is the primary diagnostic criterion for primary graft failure. Therefore, we investigated LV function of implanted hearts at 24 hours post operation. Significantly impaired myocardial function (Fig. 2A-E) was observed at 24 hours after surgery in transplanted hearts with 6hr-I compared to those being stored <1 hour, as shown by decreased LVDP and dP/dt, impaired - dP/dt, reduced RPP and heart rate. The functional parameters in MSC-CM-treated donor hearts were comparable to those hearts underwent minimal ischemia (<1hr-cold storage), suggesting that MSC-CM could reverse the detrimental effects of prolonged cold ischemia on myocardial function. Of note, there were no heart rate variance (Fig. S3) and pulse pressure differences (Fig. S4) in the native hearts among groups, providing additional experimental controls not only to indicate high reproducibility of our heterotopic heart transplantation model, but also to exclude MSC-CM-improved myocardial functional preservation attributable to potential procedural variability. Furthermore, our results revealed that the CMC did not covey functional protection in donor hearts following 6hr-I (Fig. S5A-D).

Figure 2.

MSC conditioned medium (MSC-CM) preserves Left ventricular function in implanted hearts at 24-hour post transplantation. A. Left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP = LV systolic pressure – LV end diastolic pressure). B. The maximum value of the first derivative (dP/dt). C. The maximum negative value of the first derivative (- dP/dt). D. Rate Pressure Product (RPP = LVDP X Heart rate BPM). E. Normalized heart rate of the implanted hearts to native heart rate. Six-hour cold storage (cold ischemia – I) impaired donor heart function, as demonstrated by decreases in LVDP, dP/dt, RPP, and normalized heart rate and damaged -dP/dt when compared to the < 1hr-I group. However, adding MSC-CM to UW solution for donor heart preservation restored these functional parameters. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal line represents the median; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum values in all box-and-whiskers graphs. Dots represent cardiac functional measurements of heart grafts.

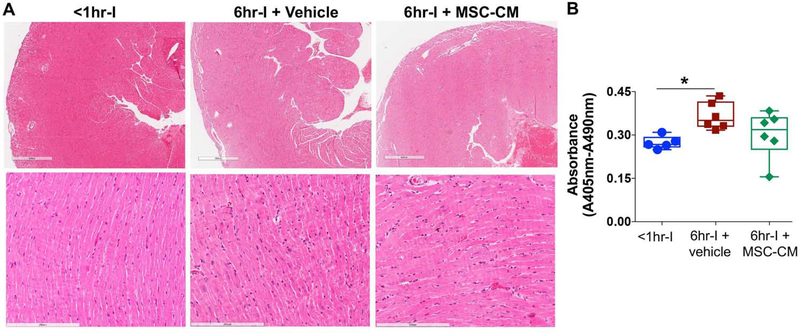

Six-hour cold ischemia induced tissue damage

Based on H&E-stained heart sections (Fig. 3A), six-hour cold ischemia did not cause much histological alterations and only resulted in slight inflammation and thrombus in heart grafts at 24h after transplantation. However, more apoptotic-related dead cells were observed in the 6hr-I hearts than in the <1hr-I group (Fig. 3B). Using MSC-CM protected the myocardium against prolonged cold ischemia, as shown by comparable dead cells between these hearts and the <1hr-I group (Fig. 3B). (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

The influence of six-hour cold ischemia (I) on myocardial microstructure and apoptosis-related cell death in donor hearts at 24 hours after implantation. A. Representative micrographs (H&E straining) showing slight inflammation and thrombus in donor hearts. Six-hour cold ischemia did not cause much histological alterations. Magnification 40X (upper panel) and 200X (lower panel). B. Myocardial apoptotic cell death at 24 hours post-transplantation. Cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragments were measured in the implanted hearts of <1hrI, 6hr-I+vehicle and 6hr-I+MSC-CM. Results expressed as absorbance. Compared to the <1hr-I group, significantly increased apoptotic-related dead cells were observed in the 6hr-I hearts, but not in 6hr-I+MSC-CM group. *p<0.01. The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal line represents the median; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum values in all box-and-whiskers graphs. Dots represent individual measurements.

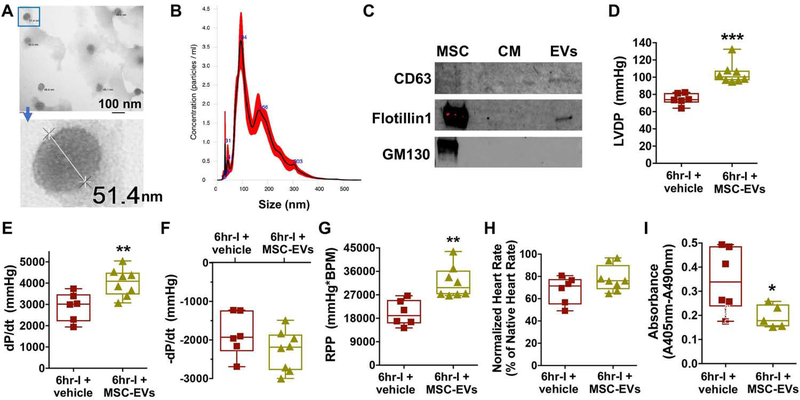

MSC extracellular vesicles conferred MSC-CM-mediated myocardial functional preservation following 6hr cold ischemia

MSC-derived EVs (exosomes and micro-vesicles) are critical components involved in paracrine protection of MSC secretome. We confirmed the presence of exosomes in the preparation of MSC-EVs by TEM (Fig. 4A). Nanosight analysis was used to determine size distribution of MSC-EVs. The most abundant nanoparticles were observed at 94 nm as seen in the peak of histogram (Fig. 4B). We also noticed > 150 nm nanoparticles in our preparation, suggesting that MSC-derived micro-vesicles were in these samples as well. We further verified the MSC-EVs by Western blot analysis. The MSC-EVs expressed exosomal markers of CD63 and Flotillin1 (Fig. 4C), whereas these EVs were free of cell debris contamination as shown by undetected signal of GM130 (a Golgi marker). Intriguingly, replacing MSC-CM with MSC-EVs to supplement UW solution for ex-vivo heart storage revealed that MSC-EVs preserved myocardial function against cold ischemia and reperfusion (Fig. 4D–4G). Likewise, using MSC-EVs reduced apoptotic-related cell death in the 6hr-I hearts compared to their untreated counterparts (Fig. 4I). To further validate the protective effect of MSC-Exo on donor heart function, we utilized MSC-CM from MSCs treated with an exosome release inhibitor (GW4849). As shown in Figure 5, depletion of exosomes in MSC-CM partially neutralized MSC-CM-mediated protection in donor hearts.

Figure 4.

Modified preservation solution by using MSC-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) provides improved protection in donor hearts during ex-vivo cold storage. A. The morphology and size of exosomes were observed under transmission electron microscope. B. Size distribution of MSC-EVs by Nanosight analysis. EVs were isolated from MSCs cultivation with serum free medium for 72 hours and 5 μg of EVs was used for Nanosight analysis. C. Western blot analysis in MSC-EVs for the presence of exosomal markers CD63 and Flotillin1. GM130 as a negative control. D. LVDP. E. dP/dt. F. - dP/dt. G. RPP. H. Normalized heart rate of the implanted hearts. I. Apoptotic-related cell death in donor hearts. Donor hearts preserved in UW solution containing MSC-EVs for 6 hours demonstrated better graft function and lower level of apoptotic-related cell death at 24 hours post-implantation than those in 6hr-I + vehicle group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal line represents the median; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum values in all box-and-whiskers graphs. Dots represent individual measurements.

Figure 5.

Exosome-depleted MSC-CM confers compromised protection in donor hearts at 24 hours post-transplantation. A. LVDP. B. dP/dt. C. - dP/dt. D. RPP. E. Normalized heart rate of the implanted hearts. F. Apoptotic-related cell death in donor hearts. CM collected after MSCs were treated with 10 μM GW4869 (an inhibitor of exosome release) for 72 hours (CMGW4869) was added to UW solution for ex vivo storage of donor hearts. CMGW4869 did not provide comparable protection in donor hearts following 6hr-cold ischemia (6hr-I) as normal MSC-CM (without using GW4869) did. Significantly decreased graft function (LVDP and RPP) was noticed in the CMGW4869 group compared to MSC-CM group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001. The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal line represents the median; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum values in all box-and-whiskers graphs. Dots represent individual measurements.

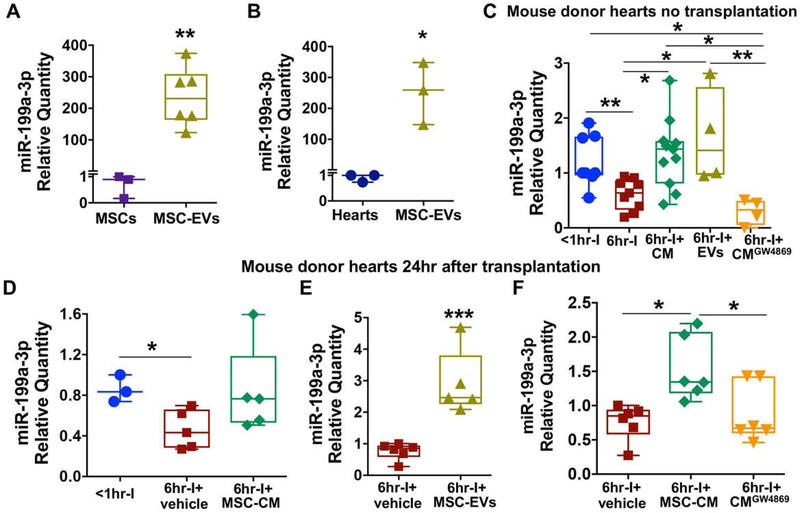

Cold ischemia reduced myocardial expression of miR-199a-3p that was enriched in MSC-EVs

Based on another individual study of the deep miRNA sequencing analysis, miR-199a-3p was identified as one of the most altered miRNAs in 6hr-I + human adipose tissue-derived MSC-CM mouse hearts (Fig. S2). Additionally, given that one of the important functions of exosomes is to transport miRNAs, we therefore selected miR-199a-3p to study the role of MSC-Exo in transferring miR to donor hearts following ex-vivo cold storage. First, we observed a markedly higher level of miR-199a-3p in MSC-EVs than in MSCs themselves (Fig. 6A) and baseline heart tissue (Fig. 6B), providing a possibility of transferring this miR from highly enriched MSC-EVs to the heart. Next, we investigated the temporal alteration of miR-199a-3p expression in mouse donor hearts following cold storage but without transplantation. We found that 6hr-cold ischemia led to significantly reduced myocardial miR-199a-3p expression (Fig. 6C), whereas using MSC-CM or MSC-EVs restored its level. In addition, depletion of exosomes in MSC-CM abolished MSC-CM- or EVs-increased miR-199a-3p levels in donor hearts (Fig. 6C). Such cold ischemia-downregulated miR-199a-3p persisted in heart grafts at 24-hour post-transplantation, but MSC-CM restored myocardial expression of miR-199a-3p (Fig. 6D). Furthermore, using MSC-EVs significantly increased myocardial miR-199a-3p levels (Fig. 6E) and inhibition of exosomes released into MSC-CM abolished MSC-CM-improved myocardial expression of this miRNA in the heart graft 24 hours post-implantation (Fig. 6F). However, we did not observe the similar results for miR-199a-5p expression in donor hearts (Fig. S6).

Figure 6.

The possibility of transferring miR-199a-3p from MSC-EVs to myocardium. A. Highly enriched miR-199a-3p in MSC-EVs compared with its cellular level in MSCs. B. Much higher levels of miR-199a-3p in MSC-EVs than in baseline mouse heart tissue. C. Using MSC-CM or MSC-EVs in UW solution for ex-vivo preservation restored miR-199a-3p level that was reduced by six-hour cold ischemia in donor hearts without transplantation, whereas much lower levels of miR-199a-3p were observed in the group of 6hr-I+CMGW4869. D. Adding MSC-CM to UW solution for ex-vivo storage preserved myocardial miR-199a-3p expression in implanted donor hearts at 24 hours post-transplantation. E. Using MSC-EVs in UW solution increased cold ischemia-downregulated miR-199a-3p in transplanted mouse hearts. F. Depletion of exosomes in MSC-CM abolished MSC-CM-preserved miR-199a-3p expression in donor hearts post implantation. After normalized to U6 snRNA, the relative miR-199a-3p transcript levels are represented as folds of a control sample in different graphs, respectively. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal line represents the median; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum values in all box-and-whiskers graphs. Dots represent individual measurements.

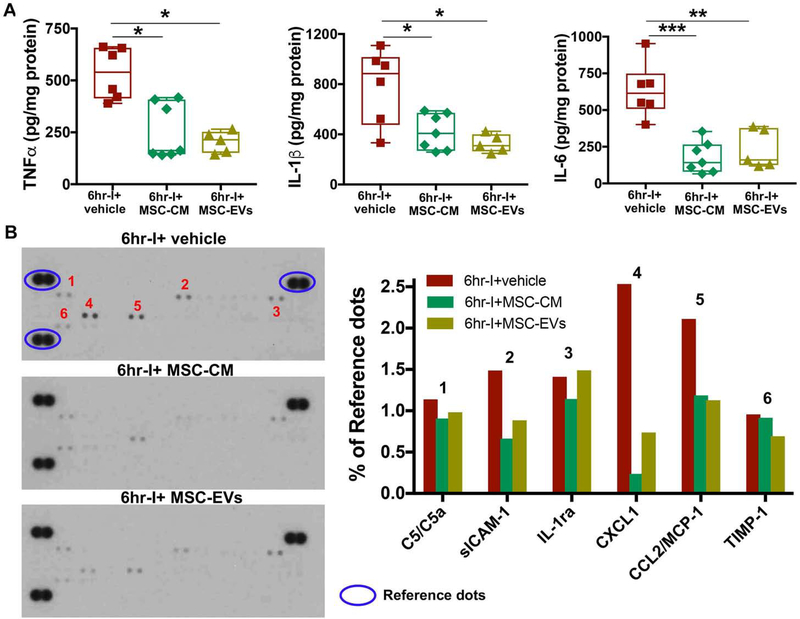

Myocardial cytokine production following ex-vivo cold storage

Locally produced cytokines contribute to cardiac dysfunction. Following 24-hour transplantation, significantly reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production (TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6) was observed in implanted hearts of 6hr-I+MSC-CM and 6hr-I+MSC-EVs compared with 6hr-I+vehicle (Fig. 7A). Moreover, by using an antibody array, MSC-CM or MSC-EVs were shown to reduce multiple cytokines/chemokines in these donor hearts, including C5/C5a, sICAM-1, CXCL1 and CCR2/MCP-1 etc. (Fig. 7B), suggesting that MSC-CM- or MSC-EV-regulated myocardial production of cytokines/chemokines may be an underlying mechanism for their mediated-protection in grafts after transplantation.

Figure 7.

Myocardial cytokine production in donor hearts 24 hours post-transplantation. A. TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels were determined in donor hearts of 6hr-I + vehicle, 6hr-I + MSC-CM and 6hr-I + MSC-EVs groups by ELISA. Adding MSC-CM or MSC-EVs to UW solution for donor heart preservation significantly decreased myocardial TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6 production at 24 hours post-transplantation compared to vehicle group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal line represents the median; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum values in all box-and-whiskers graphs. Dots represent individual measurements. B. Multiple cytokines and chemokines were detected by a membrane-based antibody array using pooled protein samples (equal amount of proteins pooled from four samples per group in 6hr-I, 6hr-I+MSC-CM, and 6hr-I+MSC-EVs). All donor hearts were collected at 24 hours post-transplantation. The bar graph shows relative level of the cytokine signal density normalized to reference dots in each group.

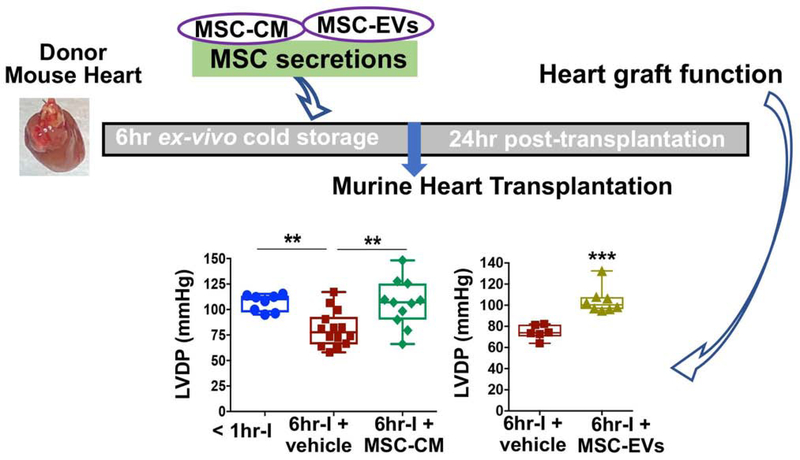

Discussion

Our results represent the first evidence that the MSC secretions, particular MSC-EVs, as an adjunct to preservation solution provides a protective effect on donor hearts against prolonged cold ischemia during ex-vivo static storage in a murine heterotopic heart transplantation model (Fig. 8). A recent paper has shown that preservation solution supplemented with MSC-CM protects the heart function in 15-month-old rats using hypothermic oxygenated perfusion for donor heart storage 21. In contrast, our study focusing on heart graft improvement during cold static storage possesses more practical benefit in the clinical setting given that cold static storage is the standard approach for organ preservation. In addition, by using miR-199a-3p as a representative miRNA, in the first time, we demonstrate that MSC-EVs serve as a vehicle to mediate the transfer of miR-199a-3p from MSCs to donor hearts during their ex-vivo cold storage. Such findings support the notion of EV-based gene therapy for miR delivery. It is worth mentioning that MSC secretions or MSC-EVs can be readily prepared in compliance with good manufacturing practice, stored as off-the-shelf material, and used for therapy promptly without the need for either cell isolation or thawing of stored cells, each of which poses significant practical barriers to widespread adoption of cell therapies in this context. More importantly, using MSC secretions or MSC-EVs as potential therapeutic modality could circumvent the risks associated with cell therapies. Therefore, our findings provide a foundation to develop cell-free, secretome-based therapies for optimization of current storage methods, thus improving donor organ function (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. MSC secretions-optimized storage solution preserves donor hearts against cold storage and improves graft function post-surgery.

Isolated donor hearts from C57BL/6 mice were infused with and subsequently stored in cold University of Wisconsin (UW) solution containing different additions. MSC-CM: mesenchymal stem cell conditioned media; EVs: MSC-derived extracellular vesicles; CMGM4869: CM from MSCs treated with exosome (Exo) release inhibitor (GM4869). The two distinct QRS complex morphologies were also noticed in the recipient mice at 1-month, 5-month, and 12-month post-transplantation by the ECG follow-up.

The heart is more susceptible to ischemic injury compared with other solid organs because of its innately high metabolic demands. I/R injury is a critical factor to influence graft function and clinical outcome after organ transplantation. Accumulated evidence from our previous studies has shown that MSC-derived paracrine action promotes cell survival and overall myocardial function while reducing inflammation and tissue damage following myocardial ischemia 9, 12–14, 22, 23. Infusion of MSC-CM at the onset of reperfusion also provides cardioprotection against myocardial I/R injury in an ex-vivo model 24. In this study, our findings that using MSC-CM improved post-implanted heart recovery, with shorter re-beating time and preserved LV contractile and diastolic function following prolonged cold ischemia, as well as reduced cell death and decreased inflammatory cytokine production extend our previous studies, in which MSC-CM protected myocardium from warm I/R injury 9; and our initial description of secretome therapeutic utility, in which MSC-secretome protected brain from ischemic injury 11.

Of note, extracellular vesicles, particularly exosomes, have emerged as essential components of the MSC secretome to mediate protective effects 25–27. Our study confirms that MSC-EVs confer protection in donor hearts following ex-vivo cold storage. MSC-EVs have been shown to transport functional proteins, mRNAs and miRNAs to target cells, acting as mediators of MSC paracrine action 17. Among these, a key form of functional RNAs in exosomes is miRNA that delivers gene regulatory information and thus can change the physiology of recipient cells. In the present study, we observed that cold ischemia led to prominent disruption of miR-199a-3p expression. However, using MSC-CM markedly restored the reduced miR-199a-3p levels in donor hearts with 6hr-cold ischemia. Our results revealed that there are highly enriched miR-199a-3p in MSC-EVs and significantly increased miR-199a-3p levels in MSC-EV-treated donor hearts, and exosome-depleted MSC-CM leads to abolished MSC-CM-restored miR-199a-3p in transplanted hearts. Taking altogether, we reasoned that miR-199a-3p could be transported from MSC exosomes into donor hearts. Notably, a single-dose intracardiac injection of miR-199a-3p has been shown to improve cardiac function following myocardial infarction 28. In addition, miR-199a-3p plays a pivotal role in regulating cardiomyocyte survival in response to simulated I/R 29. Furthermore, miR-199a-3p is identified as one of several miRNAs critical to induce cardiac regeneration 30. Therefore, during ischemic cold storage, MSC-CM- or MSC-EV-induced cardiac protection in donor hearts could partially be attributable to the MSC-EV-transferred miRs, like miR-199a-3p. However, the detailed mechanism regarding this requires further investigation in the future.

MSC secretion also contains the multiple tropic factors released from MSCs. The MSC secreted factors, including VEGF, HGF, and SDF-1, have been well defined for their effects on angiogenesis and anti-apoptosis from our previous studies 12–14, 23, 31. Such MSC-derived factors could provide protective activity to donor hearts against cold ischemia. In fact, our current study confirmed that exosome-depleted MSC-CM was still able to protect donor hearts against cold ischemia and subsequent reperfusion to some degree, suggesting the involvement of MSC-released soluble factors in donor heart protection.

We have previously shown that injection of MSCs into the heart improved cardiac function and reduced local inflammation following myocardial ischemia 9, 10. Here, we observed that adding MSC-CM or MSC-EVs to UW solution significantly decreased pro-inflammatory cytokine production (TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6) and a panel of cytokines/chemokines in heart grafts after transplantation, implying that MSC secretome-affected myocardial cytokines contribute to regulating graft function. This mechanism could play a more important role in an allotransplantation model.

In this study, we lack evidence supporting the necessity of MSC-derived exosomal miRNAs, including miR-199a-3p, for MSC-CM-based improvement in donor heart preservation. The isotransplantation utilized here also limits us on evaluating the effect of MSC secretome and MSC-EVs on modulating inflammation and immune responses between transplanted heart and recipient. Clarifying these mechanisms and the implications of MSC-Exo miRNAs in donor heart preservation will require further study in the future. Albeit these limitations, our study provides the important translational evidence that the presence of MSC-CM or MSC-EVs in ex-vivo storage solution protects donor hearts against prolonged cold ischemia and improves organ function after transplantation in a mouse model. Additionally, this initial study indicates that MSC-EV-mediated intercellular transport of miRNAs may be used as EV-based gene therapy for miRNA delivery in the heart transplant field.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Schematic shows overview of steps for concentrated MSC-CM, MSC-EVs (A), and concentrated MSC-CMGW4869 (B). Human MSCs were purchased from the Lonza Inc. and characterized by the company. These cells were tested for purity by flow cytometry and for their ability to differentiate into osteogenic, chondrogentc, and adipogenic lineages. The cells were positive for CD29, CD73, CD90, CD105, and CD166, but negative for CD14, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR and CD19. We did not observe any abnormal morphology or growth rate for the MSCs during the culture. GW4869, an exosome release inhibitor (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Ml) was dissolved in DMSO to make 10 mM stock solution. Sixty μl of 10 mM GW4869 stock solution was added to 60 ml of serum-free human MSC basal medium for the MSC culture.

Figure S2. High-throughout miRNA-sequencing analysis identifies miR-199a-3p exhibiting the greatest adipose tissue-derived (ad)MSC- CM-induced change in mouse hearts following 6hr-cold ischemia (I) compared to untreated counterparts. The mouse heart samples from groups of baseline control (no ischemia), 6hr-cold ischemia in UW solution and 6hr-cold ischemia in UW solution + adMSC CM (n=4 hearts per group) have been used for deep small RNA sequencing analysis in another separate project. Shown are the five most 6hr-cold ischemia-downregulated miRNAs that were either up-regulated or preserved by adMSC CM treatment (p<0.05).

Figure S3. Heart rate of native recipient hearts and implanted hearts among groups of < 1hr-I, 6hr-I + vehicle and 6hr-I + MSC-CM (A), between 6hr-I + vehicle and 6hr-I + MSC-EVs (B). or among groups of 6hr-I + vehicle, 6hr-I + MSC-CM, and 6hr-I + MSC CMGW4869 (C). Significantly lower heart rate is noticed in transplanted hearts compared to native hearts following 6hr-cold storage ex-vivo. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal Iine represents the median; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum Values in all box-and-whiskers graphs. Dots represent individual measurements.

Figure S4. Native heart performance of recipient mice after transplantation. There is no native pulse pressure difference (systolic pressure – diastolic pressure) of abdominal aorta in recipient mice among groups. A. Comparison of pulse pressure difference among groups of <1hr-I, 6hr-I+vehicle and 6hr-I+MSC-CM. B. The pulse pressure difference between 6hr-I+vehicle, and 6hr-I+MSC-EVs. C. Native pulse pressure difference among 6hr-I+vehicle, 6hr-I+MSC-CM, and 6hr-I+MSC CMGW4869. The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal line represents the median; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum values in all box-and-whiskers graphs. Dots represent individual measurements.

Figure S5. Left ventricular function of donor hearts at 24-hour post implantation. A. LVDP; B. dP/dt; C. - dP/dt; and D. RPP Conditioned media control (cMC, collected from the centrifuge tube of Une bottom unit} did not provide protection in donor hearts following 6hr-cold ischemia compared to vehicle (serum-free media), *p<0.05, ****<0.0001. The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal line represents the media; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum values in all box-and-whiskers graphs. Dots represent individual measurements.

Figure S6. The levels of miR-199a-5p in donor hearts following cold storage but without transplantation. Six hour-cold ischemia did not change myocardial miR-199a-5p expression. Adding MSC-EVs, but not MSC-CM, to UW solution for 6hr-donor heart preservation increased myocardial miR-199a-5p levels. * p<0.05 vs. all other groups. The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal line represents the median; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum values in all box-and- whiskers graphs. Dots represent individual measurements.

Video 1: Surgical procedure for murine heterotopic heart transplantation using cuff technique. The anastomoses between the donor heart and the recipient animal were performed using the cuffs to connect donor pulmonary artery to recipient right external jugular vein and donor aorta to recipient common carotid artery, respectively.

Central Picture.

Central picture legend: MSC secretions improve donor heart preservation, thus improving graft function post-surgery.

Central Message: When added to ex-vivo preservation solution, MSC-CM and MSC-EVs ameliorate cold ischemia-induced myocardial damage in donor hearts and improve donor heart function post transplantation.

Perspective Statement.

Our findings provide a foundation to develop cell-free, stem cell secretion-based therapies for optimizing current storage methods of donor organs, thus prolonging the time for ex-vivo preservation of donor hearts, increasing the usage of available donor organs, and improving graft function and patient outcomes post-transplantation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. George Sandusky and Victoria Sefcsik from Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at IU School of Medicine (IUSM) for their technical assistance in acquiring and analyzing histological images. We thank Mrs. Caroline Miller from the Electron Microscopy Center at IUSM for her technical assistance in acquiring transmission electron microscopy image. We thank Drs. Kanhaiya Singh and Abhishek Sen from Division of Plastic Surgery at IUSM for their technical assistance in Nanosight analysis. We also thank Dr. Lava Timsina for his consulting assistance in statistical analysis.

Funding: This study is partially supported by an award from the Methodist Health Foundation (to IW and MW), by an NIH grant (R56 HL139967 to MW), by the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute via a Project Development Team pilot grant (Grant # UL1TR001108), and by a Veterans Affairs Merit Review grant (I01 BX003888 to KLM). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Glossary of Abbreviations

- CM

conditioned medium

- cMC

conditioned media control

- dP/dt

the derivative of left ventricular pressure over time

- Exo

exosomes

- EVs

extracellular vesicles

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- I/R

ischemia/reperfusion

- LVDP

left ventricular developed pressure

- miR

micro-RNA

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cell

- RPP

rate pressure product

- TEM

transmission electron microscope

- UW

University of Wisconsin

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Messer S, Large S. Resuscitating heart transplantation: the donation after circulatory determined death donor. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young JB, Hauptman PJ, Naftel DC, et al. Determinants of early graft failure following cardiac transplantation, a 10-year, multi-institutional, multivariable analysis. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson MR, Meyer KH, Haft J, Kinder D, Webber SA, Dyke DB. Heart transplantation in the United States, 1999–2008. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1035–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christie JD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-seventh official adult lung and heart-lung transplant report−−2010. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:1104–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chullikana A, Majumdar AS, Gottipamula S, et al. Randomized, double-blind, phase I/II study of intravenous allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells in acute myocardial infarction. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:250–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suncion VY, Ghersin E, Fishman JE, et al. Does transendocardial injection of mesenchymal stem cells improve myocardial function locally or globally?: An analysis from the Percutaneous Stem Cell Injection Delivery Effects on Neomyogenesis (POSEIDON) randomized trial. Circ Res. 2014;114:1292–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigo SF, van Ramshorst J, Hoogslag GE, et al. Intramyocardial injection of autologous bone marrow-derived ex vivo expanded mesenchymal stem cells in acute myocardial infarction patients is feasible and safe up to 5 years of follow-up. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2013;6:816–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heldman AW, DiFede DL, Fishman JE, et al. Transendocardial mesenchymal stem cells and mononuclear bone marrow cells for ischemic cardiomyopathy: the TAC-HFT randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311:62–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang M, Tan J, Wang Y, Meldrum KK, Dinarello CA, Meldrum DR. IL-18 binding protein-expressing mesenchymal stem cells improve myocardial protection after ischemia or infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17499–17504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang M, Tsai BM, Crisostomo PR, Meldrum DR. Pretreatment with adult progenitor cells improves recovery and decreases native myocardial proinflammatory signaling after ischemia. Shock. 2006;25:454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei X, Du Z, Zhao L, et al. IFATS collection: The conditioned media of adipose stromal cells protect against hypoxia-ischemia-induced brain damage in neonatal rats. Stem Cells. 2009;27:478–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai L, Johnstone BH, Cook TG, et al. Suppression of hepatocyte growth factor production impairs the ability of adipose-derived stem cells to promote ischemic tissue revascularization. Stem Cells. 2007;25:3234–3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang M, Crisostomo PR, Herring C, Meldrum KK, Meldrum DR. Human progenitor cells from bone marrow or adipose tissue produce VEGF, HGF, and IGF-I in response to TNF by a p38 MAPK-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R880–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rehman J, Traktuev D, Li J, et al. Secretion of angiogenic and antiapoptotic factors by human adipose stromal cells. Circulation. 2004;109:1292–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gnecchi M, He H, Liang OD, et al. Paracrine action accounts for marked protection of ischemic heart by Akt-modified mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Med. 2005;11:367–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M, Tan J, Coffey A, Fehrenbacher J, Weil BR, Meldrum DR. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3-stimulated hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha mediates estrogen receptor-alpha-induced mesenchymal stem cell vascular endothelial growth factor production. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:163–171, 171 e161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shao L, Zhang Y, Lan B, et al. MiRNA-Sequence Indicates That Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Exosomes Have Similar Mechanism to Enhance Cardiac Repair. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:4150705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Gu H, Turrentine M, Wang M. Estradiol treatment promotes cardiac stem cell (CSC)-derived growth factors, thus improving CSC-mediated cardioprotection after acute ischemia/reperfusion. Surgery. 2014;156:243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Yoshioka Y, Takeshita F, Matsuki Y, Ochiya T. Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:17442–17452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oberhuber R, Cardini B, Kofler M, et al. Murine cervical heart transplantation model using a modified cuff technique. J Vis Exp. 2014:e50753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korkmaz-Icoz S, Li S, Huttner R, et al. Hypothermic perfusion of donor heart with a preservation solution supplemented by mesenchymal stem cells. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38:315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markel TA, Wang Y, Herrmann JL, et al. VEGF is critical for stem cell-mediated cardioprotection and a crucial paracrine factor for defining the age threshold in adult and neonatal stem cell function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H2308–2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang C, Gu H, Zhang W, Manukyan MC, Shou W, Wang M. SDF-1/CXCR4 mediates acute protection of cardiac function through myocardial STAT3 signaling following global ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1496–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angoulvant D, Ivanes F, Ferrera R, Matthews PG, Nataf S, Ovize M. Mesenchymal stem cell conditioned media attenuates in vitro and ex vivo myocardial reperfusion injury. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lai RC, Arslan F, Lee MM, et al. Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. 2010;4:214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baglio SR, Pegtel DM, Baldini N. Mesenchymal stem cell secreted vesicles provide novel opportunities in (stem) cell-free therapy. Front Physiol. 2012;3:359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eirin A, Riester SM, Zhu XY, et al. MicroRNA and mRNA cargo of extracellular vesicles from porcine adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Gene. 2014;551:55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lesizza P, Prosdocimo G, Martinelli V, Sinagra G, Zacchigna S, Giacca M. Single-Dose Intracardiac Injection of Pro-Regenerative MicroRNAs Improves Cardiac Function After Myocardial Infarction. Circ Res. 2017;120:1298–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park KM, Teoh JP, Wang Y, et al. Carvedilol-responsive microRNAs, miR-199a-3p and −214 protect cardiomyocytes from simulated ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;311:H371–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eulalio A, Mano M, Dal Ferro M, et al. Functional screening identifies miRNAs inducing cardiac regeneration. Nature. 2012;492:376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang C, Gu H, Yu Q, Manukyan MC, Poynter JA, Wang M. Sca-1+ cardiac stem cells mediate acute cardioprotection via paracrine factor SDF-1 following myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Schematic shows overview of steps for concentrated MSC-CM, MSC-EVs (A), and concentrated MSC-CMGW4869 (B). Human MSCs were purchased from the Lonza Inc. and characterized by the company. These cells were tested for purity by flow cytometry and for their ability to differentiate into osteogenic, chondrogentc, and adipogenic lineages. The cells were positive for CD29, CD73, CD90, CD105, and CD166, but negative for CD14, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR and CD19. We did not observe any abnormal morphology or growth rate for the MSCs during the culture. GW4869, an exosome release inhibitor (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Ml) was dissolved in DMSO to make 10 mM stock solution. Sixty μl of 10 mM GW4869 stock solution was added to 60 ml of serum-free human MSC basal medium for the MSC culture.

Figure S2. High-throughout miRNA-sequencing analysis identifies miR-199a-3p exhibiting the greatest adipose tissue-derived (ad)MSC- CM-induced change in mouse hearts following 6hr-cold ischemia (I) compared to untreated counterparts. The mouse heart samples from groups of baseline control (no ischemia), 6hr-cold ischemia in UW solution and 6hr-cold ischemia in UW solution + adMSC CM (n=4 hearts per group) have been used for deep small RNA sequencing analysis in another separate project. Shown are the five most 6hr-cold ischemia-downregulated miRNAs that were either up-regulated or preserved by adMSC CM treatment (p<0.05).

Figure S3. Heart rate of native recipient hearts and implanted hearts among groups of < 1hr-I, 6hr-I + vehicle and 6hr-I + MSC-CM (A), between 6hr-I + vehicle and 6hr-I + MSC-EVs (B). or among groups of 6hr-I + vehicle, 6hr-I + MSC-CM, and 6hr-I + MSC CMGW4869 (C). Significantly lower heart rate is noticed in transplanted hearts compared to native hearts following 6hr-cold storage ex-vivo. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal Iine represents the median; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum Values in all box-and-whiskers graphs. Dots represent individual measurements.

Figure S4. Native heart performance of recipient mice after transplantation. There is no native pulse pressure difference (systolic pressure – diastolic pressure) of abdominal aorta in recipient mice among groups. A. Comparison of pulse pressure difference among groups of <1hr-I, 6hr-I+vehicle and 6hr-I+MSC-CM. B. The pulse pressure difference between 6hr-I+vehicle, and 6hr-I+MSC-EVs. C. Native pulse pressure difference among 6hr-I+vehicle, 6hr-I+MSC-CM, and 6hr-I+MSC CMGW4869. The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal line represents the median; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum values in all box-and-whiskers graphs. Dots represent individual measurements.

Figure S5. Left ventricular function of donor hearts at 24-hour post implantation. A. LVDP; B. dP/dt; C. - dP/dt; and D. RPP Conditioned media control (cMC, collected from the centrifuge tube of Une bottom unit} did not provide protection in donor hearts following 6hr-cold ischemia compared to vehicle (serum-free media), *p<0.05, ****<0.0001. The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal line represents the media; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum values in all box-and-whiskers graphs. Dots represent individual measurements.

Figure S6. The levels of miR-199a-5p in donor hearts following cold storage but without transplantation. Six hour-cold ischemia did not change myocardial miR-199a-5p expression. Adding MSC-EVs, but not MSC-CM, to UW solution for 6hr-donor heart preservation increased myocardial miR-199a-5p levels. * p<0.05 vs. all other groups. The upper and lower borders of the box indicate the upper and lower quartiles; the middle horizontal line represents the median; and the upper and lower whiskers show the maximum and minimum values in all box-and- whiskers graphs. Dots represent individual measurements.

Video 1: Surgical procedure for murine heterotopic heart transplantation using cuff technique. The anastomoses between the donor heart and the recipient animal were performed using the cuffs to connect donor pulmonary artery to recipient right external jugular vein and donor aorta to recipient common carotid artery, respectively.