Abstract

Surra, a haemoprotozoan parasitic disease even in subclinical form poses a challenge in terms of diagnosis and management to animal health practitioners and policy makers as well; eventually imparting financial loss to the livestock holders. A systematic study was designed to assess the seroprevalence of surra in cattle and associated climatic risk factors, by collecting 480 serum samples across the eight districts of Mizoram during 2017–2019. The apparent and true seroprevalence detected by card agglutination test was 37.08% (CI at 95%: 32.88–41.49) and 36.59% (CI at 95%: 32.4–40.99) whereas by recombinant Variable Surface Glycoprotein based indirect ELISA was 41.88% (CI at 95%: 37.5–46.3) and 40.35% (CI at 95%: 36.02–44.76) respectively. Climate parameters which influence vector population were extracted from their respective database and were correlated with seroprevalence data. Linear discriminant analysis revealed that air temperature, relative humidity and diurnal temperature range, leaf area index and soil moisture as significant risk factors discriminating seropositive and seronegative data sets classified by indirect ELISA. This study is the first report on seroprevalence of surra in cattle of Mizoram and the situation demands deployment of intervention strategies in order to assess the endemicity of the disease and thereby preventing the economic losses.

Keywords: Trypanosoma evansi, CATT, ELISA, Climate parameters, Mizoram

Introduction

Trypanosomosis commonly known as surra is a chronic wasting disease of cattle caused by the flagellated hemoprotozoan parasite,Trypanosoma evansi. It is the most prevalent and pathogenic trypanosome throughout the tropical and subtropical areas of the world owing to its ability of mechanical transmission by hematophagous tabanid flies as well as its ability to infect a wide range of domestic and wild animals (Aregawiet al. 2019; Luckins 1988). The economic losses caused by surra in the tropics is mainly due to chronic form of the disease in cattle resulting in severe weakness, abortion, infertility, reduced milk yield, weight loss and reduced drought capabilities that later lead to neuropathy and immune suppression coupled with anemia and eventually death of the animal (Desquesnes et al. 2013; Rodrigues et al. 2009). The economic loss due to surra in central India during year 2011 revealed significant losses in large ruminants and loss per animal was estimated as INR 3328, INR 6193 and INR 9872 in case of non-descript cattle, crossbred cattle, and buffalo respectively (Singh et al. 2014).The value addition to cattle due to surra treatment was estimated to be US $84 per animal/year (Dobson et al. 2009). Though the treatment against the disease is well established, the recovered and sub clinically infected animals serving as carrier of infection without exhibiting any clinical manifestations remain a hurdle in effective management of the disease (Sengupta et al. 2014). Hence, detection and treatment of carrier animals will be a crucial step towards effective control of the disease.

The CATT/T.evansi remains as the gold standard test for detection of surra as per Office International des Epizooties (OIE) but the sensitivity of the test is compromised (Songa and Hamers 1988). Recombinant protein based indirect ELISA has been widely used for detection of the carrier animals (Rudramurthy et al. 2018; Sengupta et al. 2014, 2016). These tests can be used for conducting epidemiological studies and also to monitor the effective implementation of control strategies against trypanosomosis. In addition, climate factors play a crucial role in breeding and propagation of vectors in the environment. Identification of risk factors will facilitate in channeling the available resources to disease prone areas thereby assisting in disease control. However,such systematic studies on prevalence of haemoprotozoan diseasesof cattle from North-eastern region of India, especially from Mizoram are scanty (Ghosh et al. 2018)and there is no previous report of surra from this state. So the current study was designed to determine the seroprevalence of surra in cattle for the first time by using a systematic random sampling across the eight districts of Mizoram using recombinant Variable Surface Glycoprotein (r-VSG) based indirect ELISA (iELISA) in comparison with OIE reference diagnostic test along with analysis of climatic risk factors which are influencing vector population.

Materials and methods

Study area and sampling index

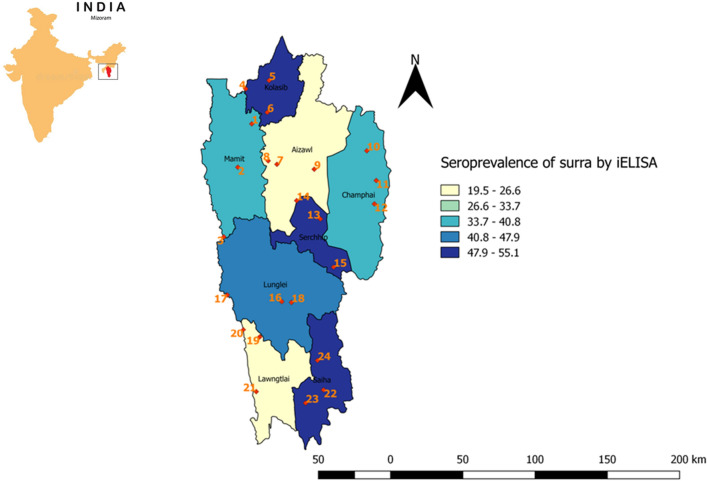

Cattle serum samples were randomly collected from eight districts of Mizoram during January 2017–December 2019 (Fig. 1). To study the seroprevalence, sample frame was derived with an expected disease prevalence of 50% with confidence level of 95% and a desired absolute precision of 5% (Sharma et al. 2019). The sample size was further verified using formula n = Z2 – P (1 − P)/d2 [(where, n is the sample size, Z is the Z statistic for a level of confidence (95%), P is the expected prevalence or proportion (on the scale of zero to one); d defines precision)] (Naing et al. 2006). Animals were selected based on probability proportion to cattle population. Cattle population, according to the 19th Livestock census of India was used for sampling (www.dahd.nic.in). The villages from each district were numbered as in the census list. Three villages from each district were chosen randomly by picking a 3 number combination between one and nth number of villages in that particular district. A total of 480 serum samples from 24 villages across the eight districts were considered for the study representing the agro-climatic zones of the entire state (Table 1). Approximately 5 ml blood from the jugular vein of cattle was collected in a serum vacutainer and extracted serum was stored in refrigerator until use.

Fig. 1.

Map showing the point (village) of sample collection and district wise seroprevalence (%) of surra detected by iELISA across the eight districts of Mizoram

Table 1.

Details of district wise cattle population, villages from where samples collected along with their latitude and longitude co-ordinates and agro-climatic zones of the villages

| District (cattle population) |

Villages (20 samples from each village) | Geo position | Agro climatic Zone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude | Longitude | |||

|

Mamit (2711) |

1) Saitlaw | 23.970945–92.575479 | HMTHZ | |

| 2) West Phaileng | 23.700994–92.488825 | HMTZ | ||

| 3) Marpara North | 23.268192–92.401897 | HMTZ | ||

|

Kolasib (6278) |

4) Bairabi | 24.188182–92.538262 | HMTZ | |

| 5) KLB-Tuithaveng | 24.240889–92.683153 | HMTZ | ||

| 6) Kawnpui | 24.042568–92.671907 | HMTHZ | ||

|

Aizawl (6911) |

7) AZL.ITI Veng | 23.719403–92.732067 | HSTHZ | |

| 8) AZL. Tanhril | 23.741214–92.677616 | HMTHZ | ||

| 9) Saitual | 23.688703–92.963841 | HTSAZ | ||

|

Champhai (8237) |

10) Selam | 23.803495–93.29106 | HTSAZ | |

| 11) Vapar | 23.618541–93.349596 | HTSAZ | ||

| 12) New Champhai | 23.473036–93.337932 | HTSAZ | ||

|

Serchhip (2374) |

13) Lungpho | 23.379801–93.001842 | HMTHZ | |

| 14) Buhkangkawn | 23.493585–92.854686 | HMTHZ | ||

| 15) Lungkawlh | 23.080541–93.084519 | HTSAZ | ||

|

Lunglei (4576) |

16) Tiperghat-III | 22.865747–92.762262 | HSTHZ | |

| 17) Lamthai-III | 22.906542–92.423713 | HMTHZ | ||

| 18) Lunglei Zobawk | 22.860684–92.822281 | HSTHZ | ||

|

Lawngtlai (3999) |

19) Bajeisora | 22.644158–92.625267 | HMTHZ | |

| 20) Ugulsury | 22.690129–92.52339 | HMTHZ | ||

| 21) Charluitlang | 22.303793–92.603184 | HMTHZ | ||

|

Saiha (3182) |

22) Tuipang Dairy Veng | 22.31453–93.022389 | HMTHZ | |

| 23) Phura | 22.233016–92.910261 | HMTHZ | ||

| 24) Saiha college Veng | 22.497732–92.984401 | HTSAZ | ||

HMTHZ = Humid mild tropical hill zone, HMTZ = Humid mild tropical zone, HTSAZ = Humid temperate sub-alpine zone, HSTHZ = Humid sub-tropical hill zone

CATT/T. evansi

The CATT/T.evansi is a rapid direct agglutination test, which uses formaldehyde-fixed, Coomassie blue stained, freeze-dried T.evansi VAT RoTat 1.2 (Songa and Hamers 1988). The commercial card agglutination test CATT/T.evansi was used to determine the levels of serum antibodies reactive against T.evansi antigen according to manufacturer’s instructions. The kits were procured from Institute of Tropical Medicine, Belgium. The serum samples were diluted 1:4 with CATT buffer. Diluted serum (25 µl) was mixed with 45 µl of reagent on a reaction zone of the agglutination card. The card was rocked for 5 min on a flat-bed rotator at 70 rpm. A reaction is scored positive when macroscopic agglutination was visible. All the serum samples were tested in duplicate.

Antigen preparation and iELISA

Yeast (X-33 P PICZα, TEVSG) (Sengupta et al. 2016) glycerol stock culture stored at − 80 °C was revived using Yeast Extract-Peptone-Dextrose (YPD) media with zeocin (100 μg/ml) until adequate turbidity was observed. To induce the gene expression, the inoculum was subcultured intobuffered glycerolcomplex medium (BMGY, Invitrogen)and incubated for 16-18 h at 28 °C at 150 rpm(OD600 = 4). After centrifugation pellet was inoculated to buffered methanol complex medium(BMMY, Invitrogen) and induction of gene was done by addition of 100% methanol to final concentration of 0.5% at every 24 h until 3 days at 28 °C in an incubator. On 4th day after induction, cells were pelleted out at 6000 rpm/10 min and the supernatant was separated, mixed with protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific) and stored at -80 °C until purification. The recombinant protein with histidine-tag was purified by Ni–NTA affinity chromatography (Qiagen, USA). The protein concentration was quantified using spectrophotometry.

The ELISA was performed using standard protocol with an in-house developed and validated test (Sengupta et al. 2016)with necessary modifications to detect the presence of antibodies against T.evansi in serum samples. In brief, microtiter plates (Maxisorp®, Nunc) were coated with 1.5 μg/well ofpurified recombinant Variable Surface Glycoprotein (r-VSG)in Carbonate-Bicarbonate Buffer (CBB) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Overnight incubated antigen-coated plates were washed thrice with washing buffer (0.25% (v/v) Tween20 in PBS pH 7.2).The wells were blocked with 150 µl of blocking buffer [3% w/v lactalbumin enzymatic hydrolysate, 2% w/v gelatin in PBS (pH 7.2)] and plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The test and control sera were diluted in blocking buffer (1:100) and added to the respective wells (100 μl/well) and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. After proper washing, anti-bovine secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Bethyl Laboratories INC) diluted 1:14 K in blocking buffer was added to each well (100 μl/well) and further incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing, 100 μl of freshly prepared chromogen-substrate solution (ortho phenylene di-amine) containing 0.05% H2O2 was added to each well and incubated for 15–20 min at room temperature for the development of color. Finally, the enzyme–substrate reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl/well stop solution (1 N H2SO4). The color development was read at 492 nm using an ELISA microplate reader (Biorad micro plate reader, bench mark). All the field serum samples and control samples were subjected to ELISA in duplicate using r-VSG. The OD values of field samples were compared with known positive and negative samples to calculate percentage positivity (PP).The PP values for the diagnostic interpretation were calculated using the formula given below. Samples with greater than 50% PP were considered as positive.

PP = [(Test sample OD-Negative control OD)/Positive control OD- Negative control OD)] × 100

Linear discriminant analysis

A total of 10 climate parameters corresponding to the location of sample collection during the study period were considered for the study.Diurnal temperature range (DTR) was obtained from Climatic Research Unit High-Resolution Datasets (CRU TS 4.03). Rainfall (RF) was extracted from the dataset GLDAS Noah Land Surface Model L4 (GLDAS_NOAH025_M 2.1) from the website GES DISC (https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov). Relative Humidity (RH) was extracted from NCEP-DOE Reanalysis 2. Other parameters like leaf area index (LAI), normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), land surface temperature (LST) data are from MODIS (https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/). Air temperature (AT), potential evapotranspiration rate (PET), soil moisture (SM) and wind speed (WS) were also extracted from GES DISC. The negative and positive results of iELISA test were classified as 0 and 1 respectively. Mean value of each climate parameter corresponding to the location of sample collection was analyzed using linear discriminant analysis (Ward 1994) to determine the parameter discriminating the negative and positive sample sets classified on the basis of iELISA test. Significant difference of the mean values was assessed by p value coefficients at 95% confidence interval using SPSS 16.0 software.

Results

Card agglutination test revealed 178 out of 480 samples as positive for agglutination confirming 37.08% of samples having specific antibodies against T.evansi. True prevalence (TP) was calculated from the apparent prevalence at 95% confidence level by considering sample size, test sensitivity and specificity, using Epitools (https://epitools.ausvet.com.au/). True prevalence of surra by CATT assay for Mizoram state was estimated as 36.59%. District wise, Serchhip showed highest (49.55%) and Aizawl showed least (22.53%) seroprevalence of surra whereas in other 6 districts the seroprevalence ranged from 24.77 to 47.3% (Table 2). Subsequently, all480 samples were assayed by iELISA in duplicate which revealed 41.88% samples as positive for containing antibodies against T.evansi and the true prevalence was calculated as 40.35%. Among the districts, Serchhipshowed highest (55.06%) whereas Aizawl showed least seroprevalence (19.47%).The range of seroprevalence in other six districts varied from 25.09% to 53.18% (Table 2).On the contrary, in Aizawl and Lawngtlai,number of samples positive by CATT/T.evansiwere more ascompared to ELISA. However, there was no statistically significant difference in ascertaining positive by both the tests as p-values were > 0.05. True prevalence was estimated at 95% CI for year, breed, season, district and zone wise samples analyzed by CATT/T.evansi and iELISA (Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimation of true prevalence values using Epitools for the samples collected by breed, year, season, district and agro-climatic zone (HMTHZ = Humid mild tropical hill zone, HMTZ = Humid mild tropical zone, HTSAZ = Humid temperate sub-alpine zone, HSTHZ = Humid sub-tropical hill zone) wise from Mizoram state and percentage of positive samples by CATT and ELISA (Range of true prevalence at 95% CI)

| No. of samples screened | % Positive by CATT | % Positive by Indirect ELISA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breed | Indigenous | 313 | 35.46 (29.81–40.31) | 40.89 (33.54–44.27) |

| Crossbreed | 167 | 40.11 (34.07–48.84) | 43.71 (34.68–49.48) | |

| Year | 2017 | 160 | 36.25 (28.93–43.64) | 41.25 (31.95–46.9) |

| 2018 | 200 | 36 (29.31–42.47) | 43 (34.52–48.03) | |

| 2019 | 120 | 40 (32.71–50.05) | 40.83 (30.46–47.64) | |

| Season | Monsoon | 280 | 40 (35.5–46.95) | 47.85 (40.75–52.36) |

| Post monsoon | 200 | 33 (25.47–38.25) | 33.75 (24.59–37.26) | |

| District | Mamit | 60 | 24.77 (15.59–36.99) | 34.46 (23.70–47.09) |

| Kolasib | 60 | 45.04 (33.13–57.55) | 51.67 (38.97–63.49) | |

| Aizawl | 60 | 22.53 (13.8–34.56) | 19.47 (11.42–31.19) | |

| Champhai | 60 | 31.53 (21.19–44.09) | 40.08 (28.64–52.71) | |

| Serchhip | 60 | 49.55 (37.31–61.84) | 55.06 (42.55–66.96) | |

| Lunglei | 60 | 38.28 (27.04–50.93) | 43.82 (32.02–56.37) | |

| Lawngtlai | 60 | 33.78 (23.11–46.40) | 25.09 (15.85–37.33) | |

| Saiha | 60 | 47.3 (35.21–59.71) | 53.18 (40.75–65.23) | |

| Zone | HMTHZ | 220 | 46.07 (39.61–52.67) | 44.93 (38.5–51.53) |

| HMTZ | 80 | 40.54 (30.46–51.49) | 42.15 (31.93–53.09) | |

| HTSAZ | 120 | 27.03 (19.89–35.60) | 30.03 (22.55–38.75) | |

| HSTHZ | 60 | 15.77 (8.66–27) | 15.5 (8.46–26.69) | |

| Mizoram | 38268 (Total cattle population) | 480 | 36.59 (32.4–40.99) | 40.35 (36.02–44.76) |

Linear discriminant analysis

Linear discriminant analysis revealed the influence of different climate parameters on disease incidence (Table 3). Parameters with p-values < 0.05 were considered to have significant influence on disease incidence. Out of10 parameters, DTR, LAI, AT, RH and SM were found to have significant influence on disease incidence. However, NDVI, WS, LST, PET and RF did not vary significantly between the data sets. Among the significant parameters except DTR, all the other four parameters showed a positive correlation with positive data set. The mean DTR values showed a negative correlation with number of positive cases.

Table 3.

Linear discriminant analysis of climatic parameters influencing vector population with indirect ELISA results (Set A: Corresponding parameter value for the pool of samples tested negative for presence of antibodies against T.evansi; Set B: Corresponding parameter value for the pool of samples tested positive for presence of antibodies against T. evansi, Values in bold represent statistical significance of that parameter between the two data sets; Lower Wilks’ λ values are inversely proportional to value of significance)

| S. no | Parameter | Set A Mean ± SD | Set B Mean ± SD | Wilks’ λ | F-value | p-value | Discriminant function coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Diurnal Temperature range (°C) | 8.93 ± 2.03 | 8.67 ± 2.03 | 0.977 | 11.085 | 0.001 | − 2.574 |

| 2 | Leaf area index | 0.40 ± 0.11 | 0.42 ± 0.09 | 0.992 | 3.903 | 0.049 | − 0.137 |

| 3 | Normalized difference vegetation index | 0.63 ± 0.12 | 0.63 ± 0.13 | 1.000 | 0.014 | 0.907 | 1.042 |

| 4 | Wind speed(Km/h) | 2.11 ± 0.23 | 2.19 ± 0.43 | 1.000 | 0.036 | 0.849 | − 0.624 |

| 5 | Land surface temperature(°C) | 26.18 ± 2.72 | 26.02 ± 2.36 | 0.974 | 0.382 | 0.536 | – |

| 6 | Air Temperature (°C) | 22.03 ± 3.90 | 23.02 ± 3.60 | 0.984 | 7.923 | 0.005 | − 8.335 |

| 7 | Potential evapotranspiration (mm/season) | 174.35 ± 48.09 | 170.65 ± 44.21 | 0.998 | 0.737 | 0.391 | 2.007 |

| 8 | Relative Humidity (%) | 72.71 ± 20.21 | 76.85 ± 19.49 | 0.990 | 5.031 | 0.025 | 0.518 |

| 9 | Soil moisture (%) | 29.57 ± 7.85 | 31.74 ± 7.11 | 0.980 | 9.686 | 0.002 | – |

| 10 | Rainfall(Inches) | 6.55 ± 0.36 | 7.11 ± 0.86 | 0.965 | 0.065 | 0.797 | – |

Discussion

Two serological tests, both CATT and iELISA employed in the present study gave similar results with respect to seropositivity as reported earlier (Sengupta et al. 2016). As CATT/T.evansi mainly detects parasite specific IgM antibodies, it can be used to detect recent infection whereas ELISA can be used to identify latent infections as it detects specific IgG antibodies. So it is advisable to employ both the tests in the epidemiological studies (Gao et al. 2018). The results obtained by two assays used in this study converge which might be due to the repeated exposure of the same animal to infection resulting in presence of both IgM and IgG antibodies. Further, the result ofCATT is measured subjectively thereby increasing the chance of human error which gives an edge for the ELISA, which is read optically. Apart from this, ELISA can be used for serosurveillance programs since it has the advantage of mass screening making it a high throughput assay which is also applicable indiseases like fasciolosis and cysticercosis (Mezo et al. 2004; Sato et al. 2003).

Vector population studies of most species suggested that there is potentially a higher risk of mechanical transmission of blood parasites by tabanids during rainy season (Barros 2001). Increased RF has positive effect on vector population which may be a resultant of increased reproduction, release from density-dependent regulation and population expansion, though it may vary with each vector. However, in this study we found that RF did not significantly vary between positive and negative data sets. Humidity has a significant effect with respect to the fly development and behavior (Nagel 1995) albeit the effect cannot be observed beyond threshold. Mean humidity values ranging from 30-50% are favorable for the flight activity of Stomoxys spp. (Lendzele et al. 2019). However in some Dipterans the peak activity attains at RH between 30 and 90% (Hogsette et al. 1989; Rowley et al. 1968).Hence a lot also depends on the behavioral niche of individual vector species. Increased air humidity also indirectly favors the vector population by reducing the mortality rates (Ogden and Lindsay 2016). Current analysis revealed that samples with corresponding high RH values were more often tested positive than with a lower RH value. The rise in temperature increases the spreading rates of parasites and pathogens by conferring prolonged periods of transmission (Marcogliese 2008). It was observed that when AT is about 19–20 °C, the peaks of abundance of Tabanid population was high (Krcmar 2005). Such ranges of air temperature are also prevalent in this state and these conditions should be favoring vector populations which transmit the disease. A high DTR value indicates the increase in the difference between maximum and minimum temperature which also mean that vector has to survive a broader temperature range. Many studies have reported the influence of temperature on occurrence of the fly but very limited studies have defined the degree of significance of this parameter (Krüger and Krolow 2015). In this analysis we found DTR was negatively correlated with the number of positive serology results and the correlation was significant statistically. Rise in temperature-related parameter like LST lead to a low suitability index in Glossina species (Dicko et al. 2015) and similar inverse relation between LST and seropositive results were observed, yet not statistically significant. Since temperature is an important factor determining vector abundance and each of this individual temperature parameter have a different influence on vector population. Earlier reports showed the correlation between NDVI and vector population as linear although it varies with each species (Rogers and Randolph 1991; Rogers et al. 1996). LAI also considered as a principal factor since it influence vector population by providing shade and host availability (Robinson et al. 1997). However both the vegetation cover parameters NDVI and LAI were not significant between the two data sets analyzed here. The PET though not directly related to vector abundance the ratio of evapotranspiration over rainfall is crucial in maintenance of RH of that particular area (Koenraadt et al. 2004). The SM is also an important factor contributing to prolonged suitability and continuous growth periods (Wogayehu et al. 2017) hence reduced SM can affect populations by faster egg desiccation in the soil and there by inhibiting the vector abundance (Menta and Remelli 2020). Though the disease is now in a sub-clinical status as per our observation, the gradual change in climate parameters in tandem with other risk factors (Sharma et al. 2015; Van den Bossche et al. 2010) may shift the paradigm in favor of the parasite which may lead transformation of subclinical form of disease to clinical form.

Conclusion

Linear discriminant analysis performed in the current study along with seroprevalence data and climate parameters revealed that DTR, LAI, AT, RH and SM as potential climatic risk factors. It appears to be a first reportregarding trypanosomosis in the state of Mizoram which was conducted across all eight districts revealed the existence of disease in subclinical form. This study also highlighted the need of a sensitive, robust and high throughput technique for conducting large scale serosurveillance programs. This report can also help the policy makers to make a strategy to screen out and treat the carrier animals for successful control of the disease in the state. The study also brings about the need of a comprehensive study to capture the actual dynamics of vector-parasite-host interaction which are maintaining the endemicity of the disease in the study area.

Acknowledgement

This research was financially supported by Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India, under the Project BT/PR16895/NER/95/342/2015 (AAB/2015/55). Authors also thank Dr.Hmangaihsanga Tochhong, JRF at Department of parasitology, CVSc & AH, Aizawl, Mizoram and Mr.Dheeraj R, SRF at ICAR-NIVEDI, Bangalore for their support in the present study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

In compliance with the ethical standards, consent from the animal owners was taken before the sample collection and was done by registered veterinary doctor with proper care and guidelines.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aregawi WG, Agga GE, Abdi RD, Büscher P. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the global distribution, host range, and prevalence of Trypanosoma evansi. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3311-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros ATM. Seasonality and relative abundance of Tabanidae (Diptera) captured on horses in the Pantanal, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96(7):917–923. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762001000700006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desquesnes M, Holzmuller P, Lai DH, Dargantes A, Lun ZR, Jittaplapong S. Trypanosoma evansi and surra: a review and perspectives on origin, history, distribution, taxonomy, morphology, hosts, and pathogenic effects. Biomed Res Int. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/194176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicko AH, Percoma L, Sow A, Adam Y, Mahama C, Sidibé I, Dayo GK, Thévenon S, Fonta W, Sanfo S, Djiteye A. A spatio-temporal model of African animal trypanosomosis risk. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(7):e0003921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson RJ, Dargantes AP, Mercado RT, Reid SA. Models for Trypanosoma evansi (surra), its control and economic impact on small-hold livestock owners in the Philippines. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:1115–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao JM, Truc P, Desquesnes M, Vincendeau P, Courtois P, Zhang X, Li SJ, Jittapalapong S, Lun ZR. A preliminary serological study of Trypanosoma evansi and Trypanosoma lewisi in a Chinese human population. Agric Nat Resour. 2018;52(6):612–616. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Patra G, Kumar Borthakur S, Behera P, Tolenkhomba TC, Deka A, Biswas P. Prevalence of haemoprotozoa in cattle of Mizoram, India. Biol Rhythm Res. 2018;51(1):76–87. doi: 10.1080/09291016.2018.1518208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hogsette JA, Ruff JP, Jones CJ. Dispersal behavior of stable flies (Diptera: Muscidae) Misc Publ Entomol Soc Am. 1989;74:23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Koenraadt CJM, Githeko AK, Takken W. The effects of rainfall and evapotranspiration on the temporal dynamics of Anopheles gambiaess and Anopheles arabiensis in a Kenyan village. Acta Trop. 2004;90:141–153. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krcmar S. Seasonal abundance of horse flies (Diptera: Tabanidae) from two locations in eastern Croatia. J Vector Ecol. 2005;30(30):316–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger RF, Krolow TK. Seasonal patterns of horse fly richness and abundance in the Pampa biome of southern Brazil. J Vector Ecol. 2015;40(2):364–372. doi: 10.1111/jvec.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendzele SS, François MJ, Roland ZKC, Armel KA, Duvallet G. Factors influencing seasonal and daily dynamics of the genus stomoxys geoffroy, 1762 (Diptera:Muscidae), in the Adamawa Plateau. Cameroon: Int J Zool; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Luckins AG. Trypanosoma evansi in Asia. Parasitol Today. 1988;4(5):137–142. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(88)90188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcogliese DJ. The impact of climate change on the parasites and infectious diseases of aquatic animals. Rev Sci Tech. 2008;27(2):467–484. doi: 10.20506/rst.27.2.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menta C, Remelli S. Soil health and arthropods: from complex system to worthwhile investigation. Insects. 2020;11:54. doi: 10.3390/insects11010054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezo M, González-Warleta M, Carro C, Ubeira FM. An ultrasensitive capture ELISA for detection of Fasciola hepatica coproantigens in sheep and cattle using a new monoclonal antibody (MM3) J Parasitol. 2004;90(4):845–852. doi: 10.1645/GE-192R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel P (1995) Environmental monitoring handbook for tsetse control operations. The Scientific Environmental Monitoring Group (SEMG) (ed.). Weikersheim: Markgraf ISBN 3 8236 1249 2:323

- Naing L, Winn T, Rusli BN. Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Arch Orofac Sci. 2006;1:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden NH, Lindsay LR. Effects of climate and climate change on vectors and vector-borne diseases: ticks are different. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32(8):646–656. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson T, Rogers D, Williams B. Univariate analysis of tsetse habitat in the common fly belt of Southern Africa using climate and remotely sensed vegetation data. Med Vet Entomol. 1997;11:223–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1997.tb00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A, Fighera RA, Souza TM, Schild AL, Barros CSL. Neuropathology of naturally occurring Trypanosoma evansi infection of horses. Vet Pathol. 2009;46(2):251–258. doi: 10.1354/vp.46-2-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers DJ, Randolph SE. Mortality rates and population density of tsetse flies correlated with satellite imagery. Nature. 1991;351(6329):739–741. doi: 10.1038/351739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers DJ, Hay SI, Packer MJ. Predicting the distribution of tsetse flies in West Africa using temporal Fourier processed meteorological satellite data. Ann Trop Med Parasit. 1996;90(3):225–241. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1996.11813049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley WA, Graham CL. The effect of temperature and relative humidity on the flight performance of female Aedes aegypti. J Insect Physiol. 1968;14(9):1251–1257. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(68)90018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudramurthy GR, Sengupta PP, Ligi M, Rahman H. Antigen detection ELISA: a sensitive and reliable tool for the detection of active infection of surra. Acta Trop. 2018;187:23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato MO, Yamasaki H, Sako Y, Nakao M, Nakaya K, Plancarte A, Hashiguchi Y. Evaluation of tongue inspection and serology for diagnosis of Taenia solium cysticercosis in swine: usefulness of ELISA using purified glycoproteins and recombinant antigen. Vet Parasitol. 2003;111(4):309–322. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta PP, Rudramurthy GR, Ligi M, Roy M, Balamurugan V, Krishnamoorthy P, Rahman H. Sero-diagnosis of surra exploiting recombinant VSG antigen based ELISA for surveillance. Vet Parasitol. 2014;205(3–4):490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta PP, Ligi M, Rudramurthy GR, Balamurugan V, Rahman H. Development of ELISA exploring recombinant variable surface glycoprotein for diagnosis of surra in animals. Curr Sci. 2016;111(12):2022–2027. doi: 10.18520/cs/v111/i12/2022-2027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Singla LD, Tuli A, Kaur P, Bal MS. Detection and assessment of risk factors associated with natural concurrent infection of Trypanosoma evansi and Anaplasma marginale in dairy animals by duplex PCR in eastern Punjab. Trop Anim Health Pro. 2015;47(1):251–257. doi: 10.1007/s11250-014-0710-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Singla LD, Kaur P, Bal MS, Sumbria D, Setia R. Spatial seroepidemiology, risk assessment and haemato-biochemical implications of bovine trypanosomiasis in low lying areas of Punjab, India. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;64:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2019.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D, Kumar S, Singh B, Bardhan D. Economic losses due to important diseases of bovines in central India. Vet World. 2014;7(8):579–585. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2014.579-585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Songa EB, Hamers R. A card agglutination test (CATT) for veterinary use based on an early VAT RoTat 1/2 of Trypanosoma evansi. Ann Soc Belge Med Trop. 1988;68(3):233–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bossche P, de La Rocque S, Hendrickx G, Bouyer J. A changing environment and the epidemiology of tsetse-transmitted livestock trypanosomiasis. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26(5):236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward MP. The use of discriminant analysis in predicting the distribution of bluetongue virus in Queensland, Australia. Vet Res Commun. 1994;18(1):63–72. doi: 10.1007/BF01839261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wogayehu Y, Woldemeskel A, Olika D, Assefa M, Kabtyimer T, Getachew S, Dinede G. Epidemiological study of cattle trypanosomiasis in Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Regional State, Ethiopia: prevalence and its vector density. Eur J Biol Sci. 2017;9:35–42. [Google Scholar]