Abstract

Fucosterol, a sterol isolated from brown algae, has been demonstrated to have anti-cancer properties. However, the effects and underlying molecular mechanism of fucosterol on non-small cell lung cancer remain to be elucidated. In this study, the corresponding targets of fucosterol were obtained from PharmMapper, and NSCLC related targets were gathered from the GeneCards database, and the candidate targets of fucosterol-treated NSCLC were predicted. The mechanism of fucosterol against NSCLC was identified in DAVID6.8 by enrichment analysis of GO and KEGG, and protein–protein interaction data were collected from STRING database. The hub gene GRB2 was further screened out and verified by molecular docking. Moreover, the relationship of GRB2 expression and immune infiltrates were analyzed by the TIMER database. The results of network pharmacology suggest that fucosterol acts against candidate targets, such as MAPK1, EGFR, GRB2, IGF2, MAPK8, and SRC, which regulate biological processes including negative regulation of the apoptotic process, peptidyl-tyrosine phosphorylation, positive regulation of cell proliferation. The Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway initiated by GRB2 showed to be significant in treating NSCLC. In conclusion, our study indicates that fucosterol may suppress NSCLC progression by targeting GRB2 activated the Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway, which laying a theoretical foundation for further research and providing scientific support for the development of new drugs.

Subject terms: Cancer, Computational biology and bioinformatics

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide1. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for about 85% of lung cancer2, and mainly includes lung squamous cell carcinoma(LUSC), lung adenocarcinoma(LUAD)3. The principal treatment methods of NSCLC are chemotherapy, surgery, radiotherapy and targeted therapy4, but the five-year survival rate as low as 18%, and may lead to serious side effects and drug resistance5,6. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop effective drugs for the treatment of NSCLC.

An estimated 25% of Earth's total species lies in marine species. Many compounds in the ocean have special biological activities and chemical structures recognized as potential medicines for many diseases7,8. Most of marine plants extracts have been confirmed to have a variety of bioactivities, including anti-cancer9,10, anti-inflammatory11,12, anti-viral13,14, etc. Marine medicines derived from marine plant extracts have received more and more attention. Fucosterol belongs to algal phytosterol in ethanol extract of brown algae (a kind of macroalgae in the ocean), which has been proved to have multiple biological activities, including antioxidant15–17, anti-inflammatory18–20, anticancer21, antimicrobial22, anti-depression23, etc. Previous researches have reported fucosterol on anti-cervical cancer21, anti-leukemia24, anti-colorectal cancer25, etc., but there are few studies on the mechanism of fucosterol in treating NSCLC about its potential therapeutic targets and related pathways in detail.

In the past few years, network pharmacology, as a new discipline based on system biology and multi-direction pharmacology, can effectively implement the predictive analysis of drug action mechanisms26, identify new drug targets27, and better explain the mechanism of interactions between bioactive molecules and cellular pathways. Molecular docking technology is an advantageous tool for modernization research, which can achieve virtual screening of drugs28. Reverse molecular docking refers to the docking of a small molecule drug in a group of potential binding cavities of clinically relevant large molecule targets. Through detailed analysis of its binding characteristics, the potential small molecule targets are identified and ranked according to the binding tightness29,30.

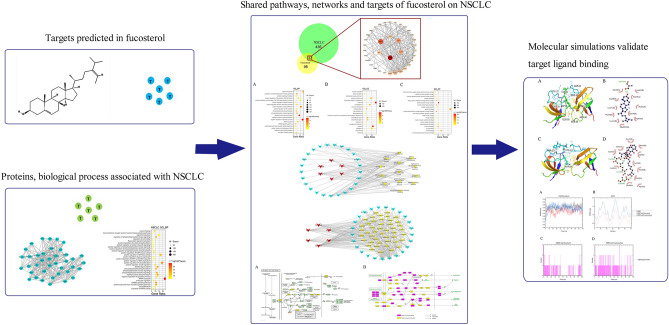

In this study, we employed network pharmacology and molecular docking to explore the effects and mechanisms of fucosterol on NSCLC. A detailed description of the procedure is shown in Fig. 1. We aimed to provide a new idea for the treatment of NSCLC and promote the development of new drugs.

Figure 1.

A stepwise workflow showed the mechanism of fucosterol against NSCLC through network pharmacology.

Materials and methods

Data preparation

Acquisition of fucosterol chemical structure

The PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) was used to retrieve the 3D chemical structure of fucosterol, saved it as “sdf” format, and converted to the mol2 format by Pymol2.4 for minimizing the MM2 energy.

Prediction and screening of fucosterol targets

Fucosterol's mol2 format was uploaded to the PharmMappper database (http://www.lilab-ecust.cn/pharmmapper/) to determine the fucosterol-related predictive targets31–33. Set parameters: Generate Conformers: Yes; Maximum Generated Conformations: 300; Select Target Set: Human Protein Target Only; Number of Reserved Matched Targets: 300. The results of predictive targets with z-score > 0 as screening criteria were retained for further analysis.

Protein and gene information correction

Fucosterol-related predictive targets were input into UniProtKB database (http://www.uniprot.org/) to collect the official symbols with the species limited to “Homo sapiens” by eliminating duplicate and nonstandard targets.

Identification of fucosterol and NSCLC common targets

NSCLC-related targets were gathered from GeneCards database (https://www.genecards.org/) using the phrase “non-small cell lung cancer” as a keyword, and the top 500 targets were retained according to the relevance score. The predictive targets of fucosterol were compared with the NSCLC-related targets in BioVenn (http://www.biovenn.nl/index.php) to identify the candidate targets of fucosterol for NSCLC treatment.

Collection of protein–protein interaction data

The data on protein–protein interaction (PPI) were obtained from STRING database 11.0 (https://string-db.org/) with uploading the candidate targets while the species limited to “Homo sapiens” and the confidence score > 0.700 (low confidence: score < 0.400; medium confidence: 0.400 < score < 0.700; high confidence: 0.700 < score < 0.900; highest confidence: score > 0.900).

Gene ontology and KEGG analysis

DAVID 6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) was applied to carry out GO enrichment analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the candidate targets. First, the species option was selected as “Homo sapiens”. Second, four analysis items were selected: KEGG pathway, cellular components, molecular functions, and biological processes. Third, enriched GO terms and KEGG pathways were screened for P-value ≤ 0.05 using the Bonferroni correction. Finally, based on the third step, KEGG pathway and the top 20 items of GO with ranking by their P-value were chosen for further analysis.

Network construction

Network construction method

The Cytoscape3.7.2 software (https://cytoscape.org/) was utilized for network topology analysis and network visualization. Construct the following networks: (1) Cluster 1 for NSCLC network; (2) Fucosterol-NSCLC PPI network; (3) Important biological processes and the candidate targets crosstalk network; (4) Target-pathway interaction network.

Cluster for NSCLC network

The disease module is a set of network components that collectively disrupts cellular function and lead to a specific disease phenotype. Owing to the disease module, the functional module and the topology module have the same meaning in the network, the function module is equal to the topology module, and the disease can be considered as interference and destruction of functional module34,35. The plug-in MCODE of Cytoscape3.7.2 software was used to analyze the protein interaction network of NSCLC to identify the dense regions, and the first cluster of results was retained.

Screening of important biological processes

The biological processes of the candidate targets retained based on the mentioned steps were compared with the results obtained by the cluster 1 network enrichment analysis of NSCLC. Then, the interaction network was established to show the associations between the important biological processes and the candidate targets.

Construction of target-pathway network

Of the enriched KEGG pathways with a P-value of < 0.05, the disease and generalized pathways were removed, and visualized the relationship with candidate targets by the target-pathway interaction network.

NSCLC-related pathways map construction

For exploring the comprehensive mechanism of fucosterol treatment of NSCLC, an integrated pathway map related to NSCLC was established, including the NSCLC disease pathway map and the key signal transduction pathways map.

Prediction of binding between fucosterol and GRB2

In this work, the initial structure of the ligand-free structure of the GRB2 (PDB code: 6SDF), was obtained from X-ray diffraction in Protein Data Bank, and the 3D structure of fucosterol (compound CID: 5281328) and Lymecycline (compound CID: 54707177) were obtained from Pubchem. Lymecycline was used as a positive control. Then, we used AutoDock 4 which based on the standard docking procedure for a rigid protein and a flexible ligand. At first, we used pymol2.4 to remove the water molecules and the original ligands from the GRB2, and then used AutoDock4 to add hydrogen and used the vina to dock the GRB2 with fucosterol and Lymecycline, and then selected the compound with the best binding effect. Finally, we used pymol2.4 and ligplot2.3 to observe and analyze the interaction and binding mode between ligand and receptor.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Lymecycline and fucosterol with GRB2 were rationally docked in our previous work. This complex was analyzed by all atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for 50 ns. All the simulations were carried out with Gromacs 2020.2 software package and gromos54a7_atb.ff force field. The force field parameters of fucosterol and Lymecycline was generated by ATB (https://atb.uq.edu.au/register.py). To ensure the total charge neutrality of the simulated system, the corresponding amount of sodium ions were added to the system to replace water molecules to produce solvent boxes of the appropriate size. Initial the energy of 50,000 steps of the whole system was minimized by (EM) at 300 K. Subsequently, the systems were equilibrated by position restraint simulations of NVT and NPT ensembles. Equilibrated systems were used to simulate a 50 ns no restraint production run. In the end MD analyses were performed, this includes root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) and Hydrogen bond analysis. The data of RMSD, RMSF and Hydrogen bond analysis is generated by Origin2019b (https://www.originlab.com/).

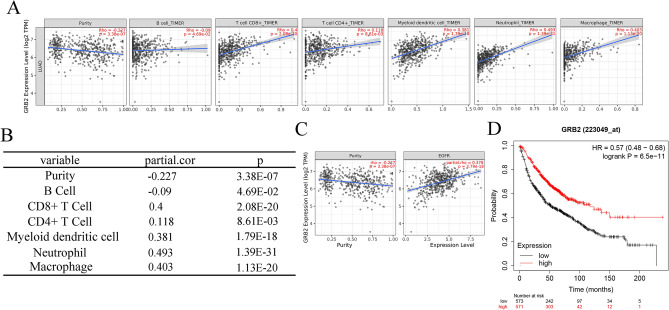

GRB2 expression and immune infiltrates

In order to explore the correlation between GRB2 expression and immune infiltrates in LUAD, the TIMER2.0 database (http://timer.cistrome.org), a friendly comprehensive tool set for systematical analysis of immune infiltrates across diverse cancer types36–38, was carried out. There were many immune cells in the TIMER database. We chose CD4 + T cells, CD8 + T cells, B cells, neutrophils, macrophages, myeloid dendritic cells to conduct a new analysis. Besides, we performed the association between gene GRB2 and EGFR after adjusting tumor purity in the correction section in TIMER2.0 database.

Prognostic values of GRB2

The correlation between GRB2 expression and survival in lung adenocarcinoma was analyzed by Kaplan–Meier plotter (http://kmplot.com/analysis/), a tool for assessing the functions of 54,675 genes and 10,188 tumor tissue samples, including breast cancer, ovarian cancer, lung cancer, and gastric cancer.

Results

Predicted target screening of fucosterol

A total 210 predictive targets were identified from the PharmMapper database, and ultimately, 135 official symbols of fucosterol related targets for limiting to “Homo sapiens” were obtained in the UniProtKB database after filtering by z-score > 0 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prediction targets of fucosterol.

| Pharma model | Gene symbol | z-score |

|---|---|---|

| 3f0r | HDAC8 | 2.82743 |

| 1qyx | HSD17B1 | 2.70536 |

| 1o6u | SEC14L2 | 2.68742 |

| 1n83 | RORA | 2.39228 |

| 1a28 | PGR | 2.2175 |

| 1ya3 | NR3C2 | 2.13319 |

| 1s9j | MAP2K1 | 2.12046 |

| 1q22 | SULT2B1 | 1.98504 |

| 1pic | PIK3R1 | 1.88125 |

| 1lv2 | HNF4G | 1.83771 |

| 1rhr | CASP3 | 1.80882 |

| 1osh | NR1H4 | 1.79715 |

| 830c | MMP13 | 1.78365 |

| 1rbp | RBP4 | 1.71609 |

| 1lho | SHBG | 1.70322 |

| 1mrq | AKR1C1 | 1.70301 |

| 1sz7 | TRAPPC3 | 1.6669 |

| 3czr | HSD11B1 | 1.65102 |

| 2piw | AR | 1.6069 |

| 1fd0 | RARG | 1.59522 |

| 1d4p | F2 | 1.55496 |

| 1gse | GSTA1 | 1.54788 |

| 1uhl | NR1H3 | 1.52908 |

| 1hrk | FECH | 1.52472 |

| 2iiv | DPP4 | 1.50916 |

| 1s0z | VDR | 1.49636 |

| 1dkf | RARA | 1.49513 |

| 2i6b | ADK | 1.38413 |

| 1o1v | FABP6 | 1.35079 |

| 1ydt | PRKACA | 1.31178 |

| 2shp | PTPN11 | 1.28799 |

| 2fjm | PTPN1 | 1.27676 |

| 2j14 | PPARD | 1.27187 |

| 1 × 0n | GRB2 | 1.2585 |

| 3bbt | ERBB4 | 1.25573 |

| 1l8j | PROCR | 1.23987 |

| 2vx0 | EPHB4 | 1.23974 |

| 1he3 | BLVRB | 1.19363 |

| 1pq2 | CYP2C8 | 1.19205 |

| 1j99 | SULT2A1 | 1.08311 |

| 1cbs | CRABP2 | 1.06101 |

| 1sm2 | ITK | 1.04514 |

| 1upw | NR1H2 | 1.03078 |

| 1qpd | LCK | 1.00159 |

| 1uym | HSP90AB1 | 0.997933 |

| 1hov | MMP2 | 0.978531 |

| 1h9u | RXRB | 0.976261 |

| 1u59 | ZAP70 | 0.97084 |

| 1fe3 | FABP7 | 0.963876 |

| 19gs | GSTP1 | 0.95545 |

| 2hzi | ABL1 | 0.954306 |

| 1yvj | JAK3 | 0.922657 |

| 1m48 | IL2 | 0.917557 |

| 1t84 | WAS | 0.909365 |

| 1dxo | NQO1 | 0.886825 |

| 1j78 | GC | 0.867991 |

| 2p4i | TEK | 0.803103 |

| 1iz2 | SERPINA1 | 0.79593 |

| 1oiz | TTPA | 0.795317 |

| 1ln3 | PCTP | 0.794336 |

| 1t4e | MDM2 | 0.78729 |

| 1xap | RARB | 0.775562 |

| 1qkt | ESR1 | 0.767258 |

| 1r9o | CYP2C9 | 0.742597 |

| 1qip | GLO1 | 0.733894 |

| 1hmt | FABP3 | 0.731703 |

| 1bl6 | MAPK14 | 0.730803 |

| 2rfn | MET | 0.721237 |

| 1i7g | PPARA | 0.707586 |

| 1pmn | MAPK10 | 0.678619 |

| 1e7a | ALB | 0.644744 |

| 2oi0 | ADAM17 | 0.634049 |

| 1cg6 | MTAP | 0.623444 |

| 1ma0 | ADH5 | 0.608206 |

| 1g3m | SULT1E1 | 0.594411 |

| 1xjd | PRKCQ | 0.557908 |

| 2uwd | HSP90AA1 | 0.555214 |

| 1oj9 | MAOB | 0.540688 |

| 1njs | GART | 0.529254 |

| 1xvp | NR1I3 | 0.502645 |

| 2pjl | ESRRA | 0.488399 |

| 1nhz | NR3C1 | 0.486782 |

| 1j96 | AKR1C2 | 0.454473 |

| 2ipw | AKR1B1 | 0.434142 |

| 1p49 | STS | 0.426598 |

| 1xbb | SYK | 0.421996 |

| 1okl | CA2 | 0.418201 |

| 2qu2 | BACE1 | 0.398063 |

| 1ih0 | TNNC1 | 0.394868 |

| 1sa4 | FNTA | 0.387846 |

| 1l6l | APOA2 | 0.385162 |

| 2fgi | FGFR1 | 0.36325 |

| 2pe0 | PDPK1 | 0.355588 |

| 2h8h | SRC | 0.34725 |

| 2itp | EGFR | 0.342717 |

| 1xor | PDE4D | 0.333997 |

| 1jqe | HNMT | 0.312737 |

| 1shj | CASP7 | 0.309471 |

| 2iku | REN | 0.285831 |

| 2pg2 | KIF11 | 0.27567 |

| 3bgp | PIM1 | 0.259029 |

| 2ywp | CHEK1 | 0.245709 |

| 1t46 | KIT | 0.241973 |

| 1s95 | PPP5C | 0.227167 |

| 1itu | DPEP1 | 0.226319 |

| 2b53 | CDK2 | 0.222033 |

| 2jbp | MAPKAPK2 | 0.216487 |

| 3cjg | KDR | 0.212231 |

| 1n7i | PNMT | 0.205326 |

| 1egc | ACADM | 0.198463 |

| 1so2 | PDE3B | 0.191704 |

| 1l9n | TGM3 | 0.19101 |

| 2bxr | MAOA | 0.187567 |

| 1hw8 | HMGCR | 0.158181 |

| 1tt6 | TTR | 0.155605 |

| 2o9i | NR1I2 | 0.148658 |

| 1 × 89 | LCN2 | 0.147746 |

| 1j4i | FKBP1A | 0.145396 |

| 1xlz | PDE4B | 0.141599 |

| 1s8c | HMOX1 | 0.137498 |

| 1tjj | GM2A | 0.121157 |

| 1mx1 | CES1 | 0.0987688 |

| 2g01 | MAPK8 | 0.0924675 |

| 1reu | BMP2 | 0.0907675 |

| 1fzv | PGF | 0.0881642 |

| 1s1p | AKR1C3 | 0.0878495 |

| 1r7y | ABO | 0.0714749 |

| 1pme | MAPK1 | 0.0689871 |

| 1g4k | MMP3 | 0.0676583 |

| 1h6g | CTNNA1 | 0.0673048 |

| 1vj5 | EPHX2 | 0.0595376 |

| 2nn7 | CA1 | 0.049744 |

| 2pin | THRB | 0.0116825 |

| 1gzr | IGF1 | 0.00629983 |

Cluster analysis for NSCLC-related targets

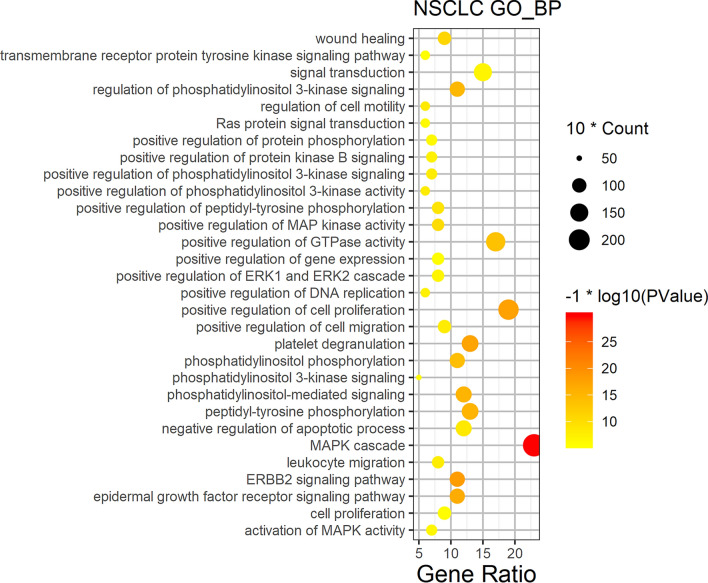

Although we selected high-relevance score of NSCLC targets from GeneCards, the NSCLC bio-network was still huge. To further analyze biological processes of the function module in NSCLC network, we obtained protein–protein interaction network (PPI) data for NSCLC, and clustered to find out the topology module of NSCLC’s PPI network. The cluster 1 was retained since it is the most significant for PPI network of NSCLC (Fig. 2), and the genes of cluster 1 was shown in Table1. Functional enrichment analyses of GO biological process on the genes of cluster 1 were performed by DAVID6.8, showing cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell cycle, angiogenesis, NSCLC gene expression, invasion and migration, signal transduction, and NSCLC related signaling pathways (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Cluster 1 for NSCLC network in Cytoscape3.7.2 (https://cytoscape.org/).

Figure 3.

Biological process bubble diagram of cluster 1. (The color scales indicate different thresholds of adjusted p-value, and the sizes of the dots represent the gene count of each term.)

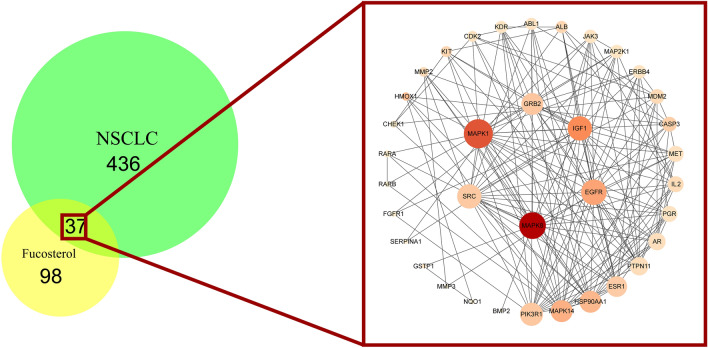

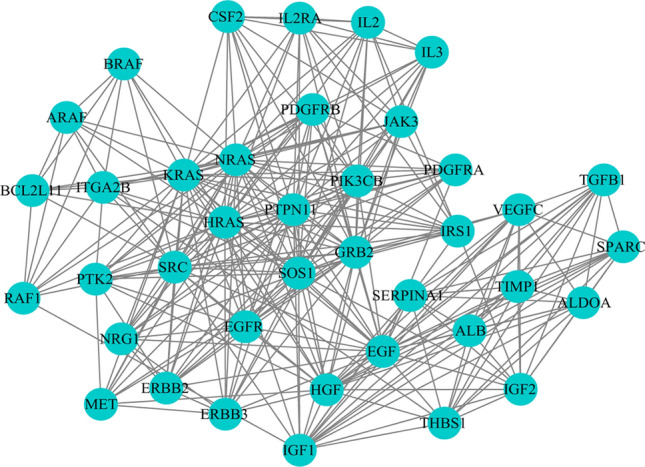

Analysis of fucosterol-NSCLC PPI network

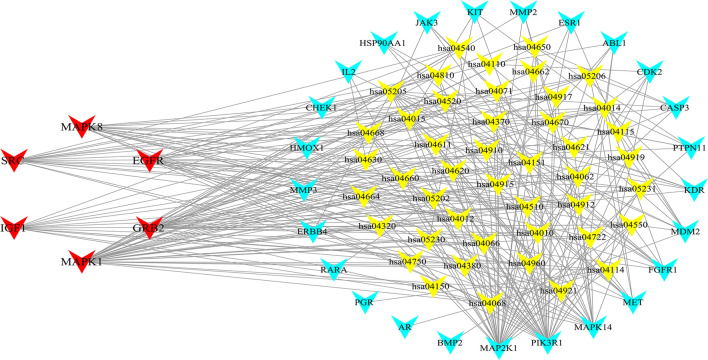

In order to construct the interaction network between proteins and dig out the core regulatory genes, the fucosterol-NSCLC PPI network of the candidate targets was performed (Fig. 4). Fucosterol shared 37 targets with NSCLC, and the network consisted of 36 nodes (one of the target proteins does not interact with others) and 177 edges. The color of each node is related to its degree; the darker nodes have the larger value of Degree. The size of the node is linked to its Edge; the bigger nodes have the larger value of Edge Betweenness. Based on the network topology analysis, the betweenness centrality is 0.0261, the average node degree is 9.83, the average closeness centrality is 0.535, which suggests the presence of a central hub between candidate targets. Six hub genes were extracted according to betweenness centrality, node degree and closeness centrality. The hub genes were speculated to play a significant role in fucosterol treated NSCLC, including EGFR, MAPK8, MAPK1, GRB2, SRC, IGF1 (Table 2).

Figure 4.

The PPI network constructed for the candidate targets of fucosterol treated NSCLC using Cytoscape3.7.2 (https://cytoscape.org/).

Table 2.

Hub genes in NSCLC treated fucosterol.

| Name | Betweenness centrality | Closeness centrality | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRB2 | 0.03441407 | 0.614035 | 16 |

| EGFR | 0.06936033 | 0.648148 | 19 |

| MAPK1 | 0.12911792 | 0.729167 | 22 |

| SRC | 0.03183796 | 0.660377 | 18 |

| IGF1 | 0.09323304 | 0.660377 | 18 |

| MAPK8 | 0.18473443 | 0.7 | 20 |

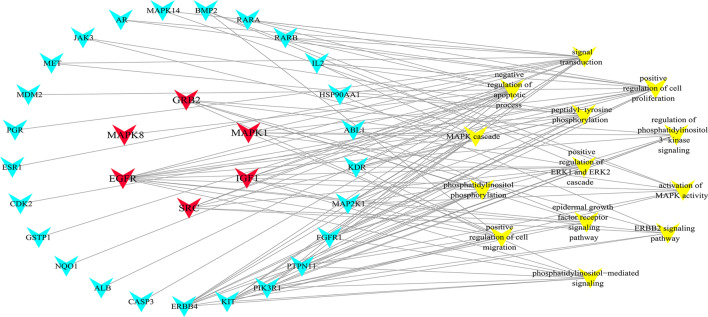

Gene ontology enrichment analysis for candidate targets

GO enrichment yields a deeper understanding on the gene function and biological significance of the candidate targets of fucosterol treated NSCLC on a systematic level. To obtain the biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components of the candidate targets, we performed a GO enrichment analysis, and displayed the top 20 significantly terms (p-value ≤ 0.05) of each module in Fig. 5. It is suggested that the candidate targets could act through protein tyrosine kinase activity, protein phosphatase binding, negative regulation of apoptotic process, peptidyl-tyrosine phosphorylation, positive regulation of cell proliferation in the nucleus, cytosol, extracellular space, nucleoplasm, extracellular region. Among them, 14 vital biological processes directly affect cluster 1 of NSCLC disease module were presented independently by connecting with the candidate targets (Fig. 6). This network diagram revealed candidate targets were mainly involved in cell proliferation and apoptosis, angiogenesis, cell migration and signal transduction, and illustrated that hub genes were strongly associated with various biological processes.

Figure 5.

GO analysis of candidate targets. GO enrichment analysis identified genes involved in (A) biological processes, (B) cellular components, and (C) molecular functions.

Figure 6.

The network made in Cytoscape3.7.2 (https://cytoscape.org/) depicted the relationship of candidate targets and important biological processes of fucosterol treated NSCLC. (Node in red is the hub gene, node in blue is the candidate targets, and yellow is the specific biological processes.)

Evaluation of target-pathway network

To explain better the mechanisms of fucosterol treatment of NSCLC at the pathway level, 73 pathways were obtained by mapping 37 candidate targets (Table 3). After getting rid of generalized and other disease terms, a total of 45 pathways and 37 candidate targets constituted the target-pathway interaction network (Fig. 7). Some targets are mapped to multiple pathways and multiple targets also regulated various pathways suggesting that candidate targets may mediate interaction and crosstalk of different pathways. The pathways may be the major factor for fucosterol's resistance to NSCLC, that is, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, VEGF signaling pathway, ErbB signaling pathway. The PI3K-Akt signaling pathway is widely recognized as a prominent cancer signaling pathway, and is closely related to affect the proliferation, survival and apoptosis of NSCLC cells39–41. Also, VEGF signaling pathway involves in tumor cell-dependent continuous vascular supply and thus has a profound effect on tumor cell growth and metastasis42. In addition, owing to interaction of ErbB receptors with many signal transduction molecules, which can activate multiple intracellular pathways, the ErbB signaling pathway plays a significant role in the development of cancer43. As mentioned, the three pathways are closely relevant to NSCLC treatment. Besides, it has been proved that fucosterol exerts antiproliferative effects to achieve the therapeutic purpose of lung cancer through targeting Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway44. And, according to the KEGG map of the three pathways (hsa04151: PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, hsa04012: ErbB signaling pathway, hsa04370: VEGF signaling pathway), all of them can activate the downstream pathway–Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway. Therefore, the three signal transduction pathways were selected as key signaling pathways for fucosterol in the treatment of NSCLC for integration and further analysis.

Table 3.

KEGG analysis of candidate targets of fucosterol for NSCLC.

| Term | Pathways | Count | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| hsa05200 | Pathways in cancer | 21 | 1.21E−16 |

| hsa05205 | Proteoglycans in cancer | 17 | 3.47E−16 |

| hsa04151 | PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 15 | 4.36E−10 |

| hsa04014 | Ras signaling pathway | 13 | 5.06E−10 |

| hsa05215 | Prostate cancer | 11 | 9.84E−12 |

| hsa04015 | Rap1 signaling pathway | 11 | 5.35E−08 |

| hsa04068 | FoxO signaling pathway | 10 | 1.42E−08 |

| hsa04510 | Focal adhesion | 10 | 5.84E−07 |

| hsa04914 | Progesterone-mediated oocyte maturation | 9 | 8.41E−09 |

| hsa04012 | ErbB signaling pathway | 9 | 8.41E−09 |

| hsa04915 | Estrogen signaling pathway | 9 | 2.36E−08 |

| hsa04550 | Signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells | 9 | 3.57E−07 |

| hsa05203 | Viral carcinogenesis | 9 | 6.39E−06 |

| hsa05218 | Melanoma | 8 | 4.93E−08 |

| hsa04917 | Prolactin signaling pathway | 8 | 4.93E−08 |

| hsa04912 | GnRH signaling pathway | 8 | 2.79E−07 |

| hsa04722 | Neurotrophin signaling pathway | 8 | 1.85E−06 |

| hsa05161 | Hepatitis B | 8 | 6.56E−06 |

| hsa04010 | MAPK signaling pathway | 8 | 2.33E−04 |

| hsa05206 | MicroRNAs in cancer | 8 | 4.92E−04 |

| hsa05230 | Central carbon metabolism in cancer | 7 | 6.71E−07 |

| hsa05214 | Glioma | 7 | 7.37E−07 |

| hsa05120 | Epithelial cell signaling in Helicobacter pylori infection | 7 | 8.84E−07 |

| hsa05220 | Chronic myeloid leukemia | 7 | 1.36E−06 |

| hsa04668 | TNF signaling pathway | 7 | 1.38E−05 |

| hsa05219 | Bladder cancer | 6 | 1.66E−06 |

| hsa05223 | Non-small cell lung cancer | 6 | 8.03E−06 |

| hsa05221 | Acute myeloid leukemia | 6 | 8.03E−06 |

| hsa04370 | VEGF signaling pathway | 6 | 1.23E−05 |

| hsa05211 | Renal cell carcinoma | 6 | 1.81E−05 |

| hsa04664 | Fc epsilon RI signaling pathway | 6 | 2.10E−05 |

| hsa04066 | HIF-1 signaling pathway | 6 | 1.11E−04 |

| hsa04660 | T cell receptor signaling pathway | 6 | 1.35E−04 |

| hsa05231 | Choline metabolism in cancer | 6 | 1.41E−04 |

| hsa04114 | Oocyte meiosis | 6 | 2.21E−04 |

| hsa04919 | Thyroid hormone signaling pathway | 6 | 2.60E−04 |

| hsa04650 | Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity | 6 | 3.43E−04 |

| hsa05169 | Epstein-Barr virus infection | 6 | 3.43E−04 |

| hsa04380 | Osteoclast differentiation | 6 | 4.76E−04 |

| hsa05160 | Hepatitis C | 6 | 5.10E−04 |

| hsa04062 | Chemokine signaling pathway | 6 | 2.30E−03 |

| hsa04810 | Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 6 | 3.89E−03 |

| hsa05213 | Endometrial cancer | 5 | 1.28E−04 |

| hsa05210 | Colorectal cancer | 5 | 2.54E−04 |

| hsa05131 | Shigellosis | 5 | 2.87E−04 |

| hsa05212 | Pancreatic cancer | 5 | 3.05E−04 |

| hsa04115 | p53 signaling pathway | 5 | 3.43E−04 |

| hsa04520 | Adherens junction | 5 | 4.29E−04 |

| hsa04540 | Gap junction | 5 | 9.67E−04 |

| hsa04750 | Inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels | 5 | 1.45E−03 |

| hsa05142 | Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) | 5 | 1.80E−03 |

| hsa04620 | Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 5 | 1.93E−03 |

| hsa04071 | Sphingolipid signaling pathway | 5 | 3.04E−03 |

| hsa04910 | Insulin signaling pathway | 5 | 5.01E−03 |

| hsa04630 | Jak-STAT signaling pathway | 5 | 5.97E−03 |

| hsa05202 | Transcriptional misregulation in cancer | 5 | 9.76E−03 |

| hsa05164 | Influenza A | 5 | 1.12E−02 |

| hsa05152 | Tuberculosis | 5 | 1.19E−02 |

| hsa04320 | Dorso-ventral axis formation | 4 | 3.25E−04 |

| hsa04621 | NOD-like receptor signaling pathway | 4 | 2.78E−03 |

| hsa04662 | B cell receptor signaling pathway | 4 | 5.03E−03 |

| hsa05133 | Pertussis | 4 | 6.34E−03 |

| hsa05145 | Toxoplasmosis | 4 | 1.80E−02 |

| hsa04670 | Leukocyte transendothelial migration | 4 | 2.02E−02 |

| hsa04110 | Cell cycle | 4 | 2.46E−02 |

| hsa04611 | Platelet activation | 4 | 2.78E−02 |

| hsa05162 | Measles | 4 | 2.95E−02 |

| hsa04921 | Oxytocin signaling pathway | 4 | 4.00E−02 |

| hsa04960 | Aldosterone-regulated sodium reabsorption | 3 | 1.66E−02 |

| hsa04930 | Type II diabetes mellitus | 3 | 2.45E−02 |

| hsa04150 | mTOR signaling pathway | 3 | 3.48E−02 |

| hsa04730 | Long-term depression | 3 | 3.70E−02 |

Figure 7.

The Target-pathway network, constructed in Cytoscape3.7.2 (https://cytoscape.org/), was built by the candidate targets and a pathway if the pathway was lighted at the target. (Yellow nodes represent signaling pathway from enrichment analysis. Blue nodes represent the candidate targets in fucosterol. Red nodes represent the hub genes screened by PPI network.)

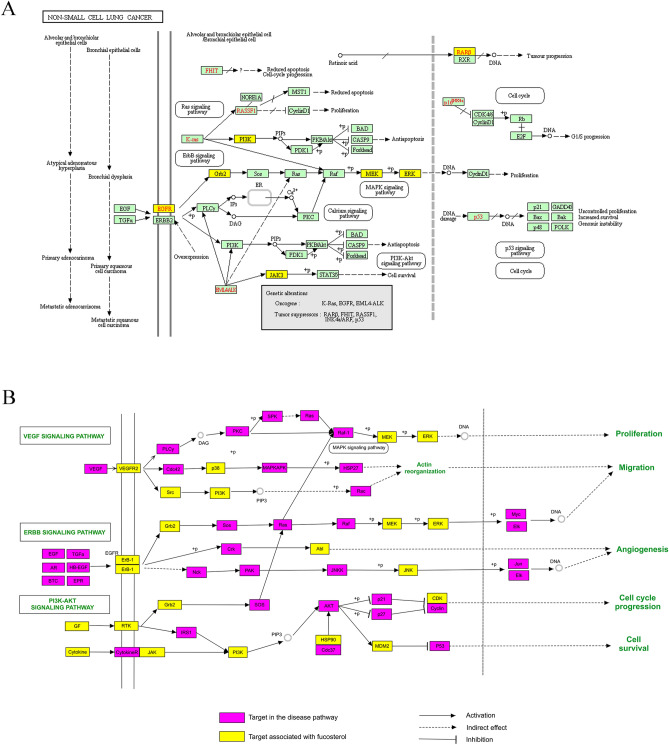

Analysis of the NSCLC-related pathways map

To intuitively explicate the complex mechanism of fucosterol treated NSCLC, an integrated pathway map (Fig. 8) was constructed by integrating the NSCLC disease pathway map and the key signal transduction pathways map that obtained from evaluating of target-pathway network. The key signal transduction pathways map comprises of three signaling pathways: hsa04151: PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, hsa04012: ErbB signaling pathway, hsa04370: VEGF signaling pathway. As shown in Fig. 8, the signaling transduction pathways and NSCLC disease pathway reflect multiple modules such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration and angiogenesis. From the perspective of NSCLC disease pathway map (Fig. 8A), fucosterol treatment of NSCLC might enable crosstalk of the inflammatory module and the tumor module, involving the joint action of multiple pathways. According to the candidate targets shown in the Fig. 8A, fucosterol may be able to achieve the purpose of treating NSCLC through activating the Ras signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, ErbB signaling pathway and MAPK signaling pathway to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis. From the perspective of the key signal transduction pathways(Fig. 8B), both VEGF signaling pathway and ErbB signaling pathway can activate downstream signals to control angiogenesis, affect cell proliferation and migration, and play a crucial role in the development and metastasis of tumors45–47. Meanwhile, the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway participates in the regulation of cell cycle progression48–50. According to this map, the three signaling pathways can jointly activate the Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway reported to play an anti-proliferation role in curing cancer44,51,52. More importantly, from the observation in this map, GRB2 can activate the downstream pathways–Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway through ErbB signaling pathway and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, which may make GRB2 one of the potential therapeutic targets for fucosterol in the treatment of NSCLC. Moreover, GRB2 was presumed to be one of the six hub genes of fucosterol therapy for NSCLC base on fucosterol-NSCLC PPI network topology analysis. Collectively, GRB2 is speculated to play an important role in fucosterol treated NSCLC. We will further discuss GRB2 targeted by fucosterol for treating NSCLC.

Figure 8.

The integrated pathways map of fucosterol in the treatment of NSCLC include (A) the non-small cell lung cancer pathway, marked in yellow as the functional targets of fucosterol, and (B) the key signal transduction pathways.

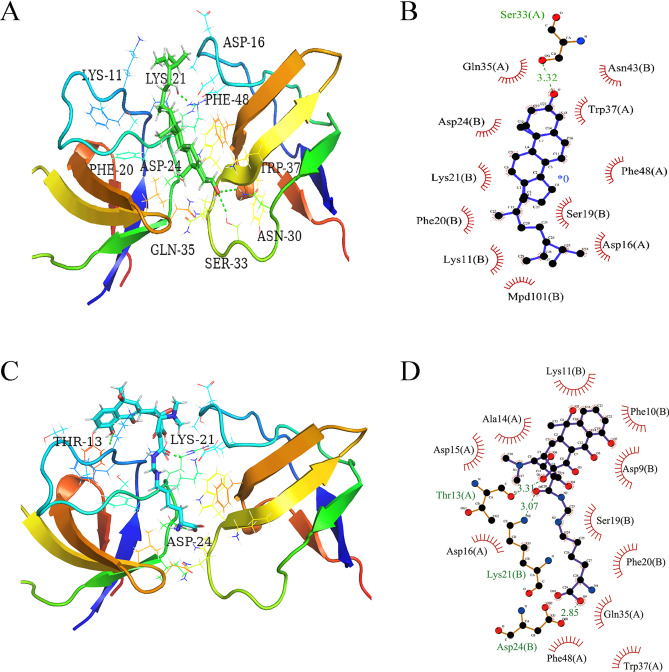

Molecular docking validation of GRB2

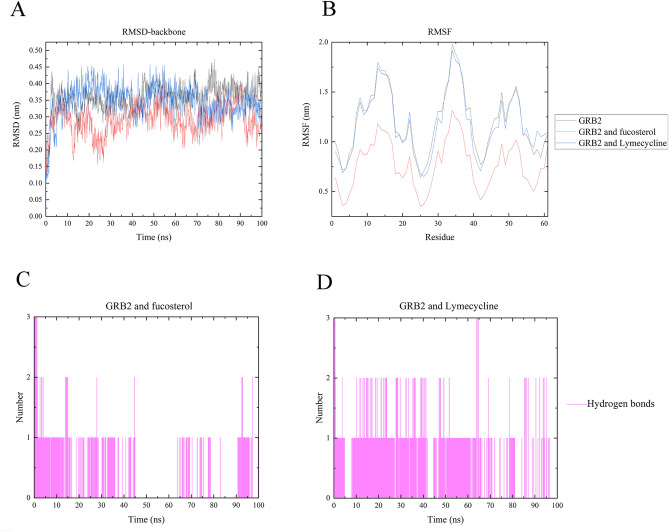

Molecular docking simulation was utilized to verify the binding ability of the fucosterol to the hub genes GRB2, and Lymecycline was selected as the positive control. The docking mode and hydrogen bonding residues of fucosterol and Lymecycline with GRB2 after docking are shown in Fig. 9. Then, the binding sites of ligands, GRB2 and the surrounding residues by software pymol2.4 and ligplot2.3 are shown in Fig. 9A. In the docking model of fucosterol and GRB2, the action site are ASP-16, LYS-11, LYS-21, Ser-33, ASN-30, which forms hydrogen bonds with Ser-33, while the interaction between ligands and surrounding residues is analyzed in Fig. 9B. (binding energy is − 9.9 kcal/mol) It was indicated that the effector-binding energy of fucosterol is mainly provided by hydrophobic interactions rather than hydrogen interactions and it also showed that GRB2 was able to provide a decent hydrophobic environment for the substrate binding. And for positive control Lymecycline, it forms hydrogen bonds with THR-13, LYS-21, ASP-24. The others are hydrophobic interaction (Fig. 9C,D) and the binding energy is − 9.7 kcal/mol. Therefore, the docking effect of fucosterol and GRB2 is not much different from that of Lymecycline, and the binding energy of fucosterol is lower than that of Lymecycline. Figure 10 shows the molecular dynamics of Lymecycline and fucosterol with GRB2 protein ligand complex and GRB2 protein (RMSD, RMSF and hydrogen bond analysis). For RMSD (Fig. 10A), in the 100 ns simulation, all the three systems reached the equilibrium state quickly. In the end, the RMSD value of the complex formed by GRB2 and fucosterol was the lowest (0.25 nm), while the RMSD value of the positive control compound Lymecycline was 0.325 nm, and the RMSD value of the separate GRB2 protein system was 0.4 nm. This suggests that in terms of stability, the fucosterol compound formed a more stable combination in the active pocket of GRB2. For RMSF (Fig. 10B), the GRB2 and fucosterol system showed lowest RMSF, in the range between 0.5 and 1.25 nm, while the other two system between 0.75 and 2.0 nm, which in the docking results fucosterol formed hydrogen bond with SER-33. In RMSF, GRB2 and fucosterol system showed the fluctuations of SER-33 decreased significantly, which means that the hydrogen bonding interaction reduces the flexibility of the system, and Lymecycline formed hydrogen bond with THR-13, LYS-21, ASP-24, the hydrogen bond also reduced the flexibility of this system, but it was not obvious to GRB2 and fucosterol. In terms of hydrogen bond analysis (Fig. 10C,D), the number of hydrogen bonds between fucosterol and GRB2 system was 0 between 45 and 63 ns, while hydrogen bonds were absent in the positive control Lymecycline for a long time. In comparison of the number and existence of hydrogen bonds, the number and duration of hydrogen bonds in Lymecycline and GRB2 system is obviously better than that in fucosterol and GRB2 system. But not only by the hydrogen bonding interaction to determine the combination of ligand and receptor, also other interactions are needed to take into consideration.

Figure 9.

Fucosterol and Lymecycline showing molecular interactions with GRB2 and 2D representation of H-bonds and hydrophobic interactions of fucosterol and Lymecycline with GRB2. (A,B) Fucosterol and GRB2. (C,D) Lymecycline and GRB2. The green stick is shown as fucosterol, the blue stick is shown as lymecycline, the hydrogen bond is shown as the green dotted line. Ligand is colored and represented in purple color, hydrogen bonda is displayed in green dotted lines, red stellations represent hydrophobic interactions, and bonds of proteins are shown in brown color. Figure (A&C) were created from Pymol2.4 (https://pymol.org), (B&D) were made in Ligplot2.3 (http://www.csb.yale.edu/userguides/graphics/ligplot/manual/index.html).

Figure 10.

MD simulation interaction diagrams for 100 ns trajectory showing RMSD, RMSF and Hydrogen bond analysis. (A) Root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the 100 ns trajectories. (B) Root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) of the 100 ns trajectories. (C) Hydrogen bond analysis of fucosterol with GRB2. (D) Hydrogen bond analysis of Lymecycline with GRB2. The red polyline is shown as GRB2 and fucosterol, the black polyline is shown as GRB2, and the blue polyline is shown as GRB2 and lymecycline. (A–D) were obtained from Origin2019b (https://www.originlab.com/).

Expression level and immune infiltrates analyses of GRB2 in NSCLC

To further explore the direct relationship between GRB2 and NSCLC, we conducted the analysis of the relationship between GRB2 expression and immune infiltrates on TIMER(2.0) database. As shown in Fig. 11A,B, the expression of GRB2 was significantly negatively associated with tumor purity while significantly positively correlated with immune cells in infiltrating levels, B cells(r = -0.09, P = 4.69e−02), CD8 + T cells(r = 0.4, P = 2.08e−20), CD4 + T cells (r = 0.118, P = 8.61e−03), macrophages(r = 0.403, P = 1.13e−20), neutrophils(r = 0.493, P = 1.39e−31) and myeloid dendritic cells(r = 0.381, P = 1.79e−18), suggesting that the GRB2 expression was mainly related to the immune infiltration of CD8 + T cells, CD4 + T cells, macrophages, neutrophils and myeloid dendritic cells. Additionally, Fig. 11C revealed that GRB2 expression is significantly positively associated with EGFR expression after adjusting tumor purity. What’s more, KM-Plotter analysis performed the result in Fig. 11D that the lower expression level of GRB2 had a better overall survival rate and gene GRB2 was an independent prognosis indictor for OS of patients with LUAD. Hence, we speculated that GRB2 exerted a more significant effect on the prognosis of LUAD, for it was highly associated with various immune cells in LUAD.

Figure 11.

The expression of GRB2 and immune infiltrates in LUAD. (A,B) Correlation of GRB2 expression with immune infiltration level in LUAD. GBR2 expression had significant positive correlations with infiltrating levels of CD8 + T cells, CD4 + T cells, macrophages, neutrophils and myeloid dendritic cells. (C) Relationship between GRB2 and EGFR in LUAD. GRB2 expression showed a strong correlation with EGFR expression after adjusting tumor purity in LUAD. (D) Prognostic values of GRB2 (n = 2437) in LUAD (OS in Kaplan–Meier plotter). Line in red with high expression while in black with low expression. Low expression of GRB2 was connected with better over survival.

Discussion

NSCLC is characterized by high malignancy, low 5-year survival rate and poor prognosis. However, for patients with advanced lung cancer, having specific predictive biomarkers and receiving targeted therapy or immunotherapy significantly improve quality of life and progression-free survival (PFS) compared to chemotherapy53–58. Hence, finding effective targeted drugs to anti-lung cancer has become an urgent problem to be solved. Network pharmacology can analyze and explain the complexity between biological systems, diseases, and drugs from a network perspective, becoming a frontier method of drug discovery59,60. Molecular docking is a structure-based drug design method, which can predict the affinity and binding pattern through the interaction between ligands and receptors, accelerate the design and screening of drugs, and provide a basis for future experimental detection61,62. Molecular dynamics simulate ligand target complexes in a given system to explore their stability and flexibility63,64. Therefore, based on network pharmacology and molecular docking simulation ligand target binding, the mechanism research of fucosterol therapy for NSCLC may serve as the foundation for the development of NSCLC targeted drugs in the future.

Based on the reverse of molecular docking technology for predicting fucosterol targets, and compare with NSCLC related targets, we obtained 37 candidate targets. Fucosterol-NSCLC PPI network analysis uncovered that fucosterol probably exerted pharmacological effects on NSCLC via 37 candidate targets, including 6 hub genes: GRB2, EGFR, MAPK1, SRC, IGF2, MAPK8. According to GO biological process analysis, 37 candidate targets were found to mainly responsible for cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, signal transduction and angiogenesis. In addition, KEGG analysis of candidate targets disclosed that fucosterol probably has therapeutic effect on NSCLC through multiple pathways like PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, VEGF signaling pathway, ErbB signaling pathway. Furthermore, it is reported that fucosterol has antiproliferative effects on human lung cancer cells by inducing apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and targeting of Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway, such as A549 and SK-LU-1 cancer cells, in addition, fucosterol could also inhibit the growth of xenografted tumours in mice44. Through the NSCLC-related pathway map, we discover that GRB2 can be acted as the trigger or initiation signal of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway by PI3K-Akt signaling pathway and ErbB signaling pathway, which may be crucial for fucosterol in the treatment of NSCLC.

Based on molecular docking, the combination of fucosterol and GRB2 can be discussed. At the same time, Lymecycline was selected as the positive control to provide the basis for future experiments. We chose to complete many key structures with higher resolution crystal structures, and then the docking site was selected in the SH3 region of GRB2, so as to influence the cell signal transduction events and achieve the therapeutic effect of cancer. RMSD, RMSF and hydrogen bond analysis were calculated using molecular dynamics simulations to infer the basic properties of ligand-target complexes-stability and flexibility. The stability of RMSD and RMSF was essential to infer good binding affinity, while hydrogen bond analysis was to compare the binding of phytosterol and Lymecycline to GRB2. The results show that the combination of GRB2 and fucosterol is stable.

Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2), a universally expressed adaptor protein, which plays a pivotal downstream mediator role in a variety of oncogenes signaling pathways and has a significant effect on signal transduction in normal and cancer cells65,66. Grb2 is a downstream protein of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) that is known to be closely related to NSCLC, and may serve as an adaptor protein to bind to phosphorylated tyrosine in the EGFR, thereby linking receptor activation to intracellular signaling cascade67–69. Simultaneously, recent research has demonstrated that the balance of Grb2 monomer–dimer is a determinant of its normal and carcinogenic functions70. Grb2 regulating angiogenesis and cell movement is highly overexpressed in tumors and may be useful as a target for anticancer agents. In the present study, we found Grb2 can be targeted by fucosterol and activate the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway to achieve the purpose for treating NSCLC44,71–73.

Conclusion

In summary, our study indicated the molecular and pharmacological mechanism of fucosterol against NSCLC from a systematic perspective. We unveil that GRB2 can serve as an anticancer target in fucosterol to initiate the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway for treating NSCLC. This strategy provides a new idea of anti-NSCLC and lays a foundation for the development of new medicines. Nonetheless, network pharmacology has certain limitations, and more experiments are needed to verify the validity of our findings. Moreover, we hope that our study will be useful for fostering innovative research of marine drugs against cancers.

Abbreviations

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- LUAD

Lung adenocarcinoma

- GRB2

Growth factor receptor-binding protein 2

- KEGG

Kyoto encyclopedia of gene and genome

- GO

Gene ontology

- PPI

Protein-protein interaction

- TIMER

Tumor immune estimation resource

Author contributions

L.X.L. conceived the idea; X.L. L.i., Y.S.Z., Z.P.L., B.X.L., Q.W. contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. L.X.L., Y.C.M. and B.X.L. wrote the manuscript; H.L., L.C., and L.X.L. reviewed the paper and provided comments, and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by the PhD Start-up Fund of Guangdong Medical University (B2019016); Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Guangdong Province (20201180); Science and Technology Special Project of Zhanjiang (2019A01009); Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2016B030309002); Basic and Applied Basic Research Program of Guangdong Province (2019A1515110201); GDNRC[2020]038; Educational Commission of Guangdong Province (4SG20138G); Fund of Southern Marine Science and Engineering GuangdongLaboratory (Zhanjiang)( ZJW-2019-007).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lin YJ, et al. Network analysis and mechanisms of action of Chinese herb-related natural compounds in lung cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 2019;58:152893. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2019.152893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2018;553:446–454. doi: 10.1038/nature25183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD, Schild SE, Adjei AA. Non-SMALL CELL LUNG CANCER: EPIDEMIOLOGY, RISK FACTORS, TREATMENT, AND SURVIVORship. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2008;83:584–594. doi: 10.4065/83.5.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keith RL, Miller YE. Lung cancer chemoprevention: current status and future prospects. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013;10:334–343. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho MM, Ng AV, Lam S, Hung JY. Side population in human lung cancer cell lines and tumors is enriched with stem-like cancer cells. Can. Res. 2007;67:4827–4833. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mora C, Tittensor DP, Adl S, Simpson AG, Worm B. How many species are there on Earth and in the ocean? PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaspars M, et al. The marine biodiscovery pipeline and ocean medicines of tomorrow. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom. 2016;96:151–158. doi: 10.1017/s0025315415002106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehra R, Bhushan S, Bast F, Singh S. Marine macroalga Caulerpa: role of its metabolites in modulating cancer signaling. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019;46:3545–3555. doi: 10.1007/s11033-019-04743-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khalifa SAM, et al. Marine natural products: a source of novel anticancer drugs. Mar. Drugs. 2019 doi: 10.3390/md17090491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernando IPS, Nah JW, Jeon YJ. Potential anti-inflammatory natural products from marine algae. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016;48:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2016.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasarri M, et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of the marine plant Posidonia oceanica (L.) Delile. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020;247:112252. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luthuli S, et al. Therapeutic effects of fucoidan: a review on recent studies. Mar. Drugs. 2019 doi: 10.3390/md17090487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qureshi D, et al. Carrageenan: a wonder polymer from marine algae for potential drug delivery applications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019;25:1172–1186. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666190425190754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee S, Lee YS, Jung SH, Kang SS, Shin KH. Anti-oxidant activities of fucosterol from the marine algae pelvetia siliquosa. Arch. Pharmacal. Res. 2003;26:719–722. doi: 10.1007/bf02976680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi JS, et al. Protective effect of fucosterol isolated from the edible brown algae, Ecklonia stolonifera and Eisenia bicyclis, on tert-butyl hydroperoxide- and tacrine-induced HepG2 cell injury. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015;67:1170–1178. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernando IPS, et al. Beijing urban particulate matter-induced injury and inflammation in human lung epithelial cells and the protective effects of fucosterol from Sargassum binderi (Sonder ex J. Agardh) Environ. Res. 2019;172:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Z, Mohamed MAA, Park SY, Yi TH. Fucosterol protects cobalt chloride induced inflammation by the inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor through PI3K/Akt pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015;29:642–647. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, et al. Fucosterol attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. J. Surg. Res. 2015;195:515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrade PB, et al. Valuable compounds in macroalgae extracts. Food Chem. 2013;138:1819–1828. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.11.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang H, et al. Fucosterol exhibits selective antitumor anticancer activity against HeLa human cervical cell line by inducing mitochondrial mediated apoptosis, cell cycle migration inhibition and downregulation of m-TOR/PI3K/Akt signalling pathway. Oncol. Lett. 2018;15:3458–3463. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.7769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 22.Santos SAO, et al. Lipophilic fraction of cultivated bifurcaria bifurcata R. Ross: detailed composition and in vitro prospection of current challenging bioactive properties. Mar. Drugs. 2017 doi: 10.3390/md15110340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhen XH, et al. Fucosterol, a sterol extracted from Sargassum fusiforme, shows antidepressant and anticonvulsant effects. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015;768:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji YB, Ji CF, Yue L. Study on human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells apoptosis induced by fucosterol. Biomed. Mater. Eng. 2014;24:845–851. doi: 10.3233/BME-130876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramos AA, Almeida T, Lima B, Rocha E. Cytotoxic activity of the seaweed compound fucosterol, alone and in combination with 5-fluorouracil, in colon cells using 2D and 3D culturing. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 2019;82:537–549. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2019.1634378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iorio F, et al. Discovery of drug mode of action and drug repositioning from transcriptional responses. PNAS. 2010;107:14621–14626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000138107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang M, Su S, Bhatnagar RK, Hassett DJ, Lu LJ. Prediction and analysis of the protein interactome in Pseudomonas aeruginosa to enable network-based drug target selection. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinzi L, Rastelli G. Molecular docking: shifting paradigms in drug discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019 doi: 10.3390/ijms20184331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duan C, Li Y, Dong X, Xu W, Ma Y. Network pharmacology and reverse molecular docking-based prediction of the molecular targets and pathways for avicularin against cancer. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2019;22:4–12. doi: 10.2174/1386207322666190206163409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen F, et al. Application of reverse docking for target prediction of marine compounds with anti-tumor activity. J. Mol. Graph Model. 2017;77:372–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Pan C, Gong J, Liu X, Li H. Enhancing the enrichment of pharmacophore-based target prediction for the polypharmacological profiles of drugs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2016;56:1175–1183. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu X, et al. PharmMapper server: a web server for potential drug target identification using pharmacophore mapping approach. Nucl. Acids Res. 2010;38:W609–614. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, et al. PharmMapper 2017 update: a web server for potential drug target identification with a comprehensive target pharmacophore database. Nucl. Acids Res. 2017;45:W356–W360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bader GD, Hogue CWV. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinform. 2003 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang K, et al. Investigating the regulation mechanism of baicalin on triple negative breast cancer's biological network by a systematic biological strategy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019;118:109253. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li T, et al. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucl. Acids Res. 2020;48:W509–W514. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li B, et al. Comprehensive analyses of tumor immunity: implications for cancer immunotherapy. Genome Biol. 2016;17:174. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1028-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li T, et al. TIMER: a web server for comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e108–e110. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou B, et al. Effect of miR-21 on apoptosis in lung cancer cell through inhibiting the PI3K/ Akt/NF-kappaB signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018;46:999–1008. doi: 10.1159/000488831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fumarola C, Bonelli MA, Petronini PG, Alfieri RR. Targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in non small cell lung cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014;90:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang J, et al. MKRN2 inhibits migration and invasion of non-small-cell lung cancer by negatively regulating the PI3K/Akt pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;37:189. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0855-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li X, Wang X, Ye H, Peng A, Chen L. Barbigerone, an isoflavone, inhibits tumor angiogenesis and human non-small-cell lung cancer xenografts growth through VEGFR2 signaling pathways. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2012;70:425–437. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1923-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hynes NE, MacDonald G. ErbB receptors and signaling pathways in cancer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mao Z, et al. Fucosterol exerts antiproliferative effects on human lung cancer cells by inducing apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and targeting of Raf/MEK/ERK signalling pathway. Phytomedicine. 2019;61:152809. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Y, Mathy NW, Lu H. The role of VEGF in the diagnosis and treatment of malignant pleural effusion in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer (Review) Mol. Med. Rep. 2018;17:8019–8030. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang D, Donner DB, Warren RS. Homeostatic modulation of cell surface KDR and Flt1 expression and expression of the vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) receptor mRNAs by VEGF. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:15905–15911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yosef Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–137. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martini M, De Santis MC, Braccini L, Gulluni F, Hirsch E. PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and cancer: an updated review. Ann. Med. 2014;46:372–383. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.912836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang BJ, et al. The Effects of autophagy and PI3K/AKT/m-TOR signaling pathway on the cell-cycle arrest of rats primary sertoli cells induced by zearalenone. Toxins (Basel) 2018 doi: 10.3390/toxins10100398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee HJ, et al. Pectolinarigenin induced cell cycle arrest, autophagy, and apoptosis in gastric cancer cell via PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Nutrients. 2018 doi: 10.3390/nu10081043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCubrey JA, et al. Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cell growth, malignant transformation and drug resistance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1773:1263–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park JI. Growth arrest signaling of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cancer. Front. Biol. (Beijing) 2014;9:95–103. doi: 10.1007/s11515-014-1299-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang JC-H, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin-based chemotherapy for EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (LUX-Lung 3 and LUX-Lung 6): analysis of overall survival data from two randomised, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:141–151. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reck M, et al. Impact of nivolumab versus docetaxel on health-related quality of life and symptoms in patients with advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer: results from the checkmate 017 study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018;13:194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rosell R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:239–246. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70393-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Solomon BJ, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:2167–2177. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hida T, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in patients with ALK -positive non-small-cell lung cancer (J-ALEX): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2017;390:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30565-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brahmer JR, et al. Health-related quality-of-life results for pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy in advanced, PD-L1-positive NSCLC (KEYNOTE-024): a multicentre, international, randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1600–1609. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30690-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li XJ, Jiang ZZ, Zhang LY. Triptolide: progress on research in pharmacodynamics and toxicology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014;155:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou W, Wang Y, Lu A, Zhang G. Systems pharmacology in small molecular drug discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:246. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saikia S, Bordoloi M. Molecular docking: challenges, advances and its use in drug discovery perspective. Curr. Drug Targets. 2019;20:501–521. doi: 10.2174/1389450119666181022153016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dias R, Timmers LFSM, Caceres RA. Evaluation of molecular docking using polynomial empirical scoring functions. Curr. Drug Targets. 2008;9:1062–1070. doi: 10.2174/138945008786949450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vlachakis D, Bencurova E, Papangelopoulos N, Kossida S. Current state-of-the-art molecular dynamics methods and applications. Adv. Protein. Chem. Struct. Biol. 2014;94:269–313. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800168-4.00007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Do PC, Lee EH, Le L. Steered molecular dynamics simulation in rational drug design. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2018;58:1473–1482. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tari AM, Lopez-Berestein G. GRB2 a pivotal protein in signal transduction. Semin. Oncol. 2001;28:142–147. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Giubellino A, Bottaro DP. Grb2 signaling in cell motility and cancer. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2008;12:1021–1033. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.8.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.da Cunha Santos G, Shepherd FA, Tsao MS. EGFR mutations and lung cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011;6:49–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kozer N, et al. Recruitment of the adaptor protein Grb2 to EGFR tetramers. Biochemistry. 2014;53:2594–2604. doi: 10.1021/bi500182x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Del Piccolo N, Hristova K. Quantifying the interaction between EGFR dimers and Grb2 in live cells. Biophys. J. 2017;113:1353–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ahmed Z, et al. Grb2 monomer-dimer equilibrium determines normal versus oncogenic function. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7354. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dharmawardana PG, Peruzzi B, Giubellino A, Bottaro DP. Molecular targeting of growth factor receptor-bound 2 (Grb2) as an anti-cancer strategy. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17:13–20. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000185180.72604.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sanches K, et al. Grb2 dimer interacts with Coumarin through SH2 domains: a combined experimental and molecular modeling study. Heliyon. 2019;5:e02869. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Roberts PJ, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3291–3310. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.