Abstract

Introduction

We aimed to explore the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in vivo as a tool to elucidate the placental phenotype in women with chronic hypertension.

Methods

In case-control study, women with chronic hypertension and those with uncomplicated pregnancies were imaged using either a 3T Achieva or 1.5T Ingenia scanner. T2-weighted images, diffusion weighted and T1/T2* relaxometry data was acquired. Placental T2*, T1 and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps were calculated.

Results

129 women (43 with chronic hypertension and 86 uncomplicated pregnancies) were imaged at a median of 27.7 weeks’ gestation (interquartile range (IQR) 23.9–32.1) and 28.9 (IQR 26.1–32.9) respectively. Visual analysis of T2-weighted imaging demonstrated placentae to be either appropriate for gestation or to have advanced lobulation in women with chronic hypertension, resulting in a greater range of placental mean T2* values for a given gestation, compared to gestation-matched controls. Both skew and kurtosis (derived from histograms of T2* values across the whole placenta) increased with advancing gestational age at imaging in healthy pregnancies; women with chronic hypertension had values overlapping those in the control group range. Upon visual assessment, the mean ADC declined in the third trimester, with a corresponding decline in placental mean T2* values and showed an overlap of values between women with chronic hypertension and the control group.

Discussion

A combined placental MR examination including T2 weighted imaging, T2*, T1 mapping and diffusion imaging demonstrates varying placental phenotypes in a cohort of women with chronic hypertension, showing overlap with the control group.

Keywords: Chronic hypertension, Placenta, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Highlights

-

•

MRI enables evaluation of the placental contribution of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

-

•

Placental MRI examination was undertaken in women with chronic hypertension.

-

•

T2-weighted imaging showed varied placental visual appearance compared to controls.

-

•

Overlap in mean T2*, T1, ADC and T2* histogram derived measures was noted.

-

•

MRI may elucidate placental dysfunction and development of adverse outcomes.

1. Introduction

Chronic hypertension complicates an estimated 3–5% of all pregnancies [1] with a rising incidence associated with a global increase in obesity and maternal age. Adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with chronic hypertension include superimposed preeclampsia, preterm delivery, low birthweight, perinatal death and an increased incidence of neonatal admission and caesarean delivery [2], occurring independent of the development of superimposed preeclampsia [3].

Altered placental structure and function may contribute to the pathophysiology of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Histological examination of placentae have demonstrated lesions related to maternal vascular malperfusion to be more prevalent in women with chronic hypertension and preeclampsia compared to those without hypertensive disorders of pregnancy [4,5]. In pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia, altered early placental perfusion is hypothesised to lead to placental oxidative stress with cellular damage of fragile villous trees and inflammation. Subsequent ischaemia-reperfusion injury alters the balance of placentally expressed antiangiogenic and angiogenic compounds which can be detected in the maternal circulation [6]. The clinical manifestation of disease is considered to relate to the interaction between the release of placentally-derived factors and subsequent maternal responses, exacerbated by pre-existing comorbidities characterised by maternal vascular endothelial dysfunction (such as chronic hypertension or renal disease) [7].

The use of magnetic resonance imaging as a tool to provide in vivo assessment of the placenta structure and function is of growing interest. Imaging sequences can be acquired within a clinically acceptable time of 15 min to acquire comprehensive assessment including T2* mapping and diffusion MRI [8]. Resultant measures of interest include the T2* relaxation time (an indicative measure of tissue oxygenation), T1 relaxation (related to oxygen tension) and measures of diffusion (assessing the microstructural properties through the random thermal microscopic translational motion of molecules). Reduced placental T2* [9], mean diffusivity values [10] and reduced mean T1 relaxation times [10] are reported in pregnancies complicated by fetal growth restriction and thus provide a promising indicator of placental dysfunction.

To our knowledge, no studies have assessed the use of magnetic resonance imaging to aid understanding of the heterogeneity of pregnancy outcomes in women with chronic hypertension. The aim of this study was to explore the use of magnetic resonance imaging as a tool to elucidate the placental phenotype in women with chronic hypertension.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

This case-control study was undertaken at St Thomas’ Hospital, London, a tertiary level maternity unit. Women with chronic hypertension attending a consultant led specialist antenatal hypertension clinic were approached in person. Women in the control group were recruited at their routine 20-week anomaly scan or self-referred to take part in the study. All women in the study (both the hypertensive and control group) gave written informed consent for this specific project (Placenta Imaging Project, IRAS 201609). This study was part of a larger body of work (Placenta Imaging Project, IRAS 201609) that aimed to optimise and develop novel magnetic resonance imaging protocols for placental assessment. Standard core protocols of imaging in our unit were adhered to that included patient positioning, monitoring during imaging, imaging time and anatomical T2-weighted imaging of the fetal brain in three orthogonal planes to the woman, suitable for volume reconstruction and clinical reporting [22].

Women were considered for inclusion in the study if they had a singleton pregnancy, were over 16 years of age, not claustrophobic and had no contraindication for magnetic resonance imaging. Chronic hypertension and preeclampsia were prospectively defined using the international consensus definition [11]. Clinical management of hypertensive women were according to national guidelines, with responsibility under the attending obstetrician. Follow up was until delivery, with the last woman enrolled delivering in August 2019. Prospective specified data collection included baseline demographic characteristics, maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Women in the chronic hypertension and the control group were prospectively recruited, all of whom were enrolled in a larger body of work (Placenta Imaging Project, IRAS 201609, REC16/LO/1573), that aimed to optimise and develop novel magnetic resonance imaging protocols for placental assessment. Women in the control group fulfilled the following prespecified criteria based on pregnancy outcome: no diagnosis of hypertensive disorder at enrolment and until delivery, no significant past medical history, no pregnancy complications (including gestational diabetes), delivery at term with birthweight between the 3rd and 97th centile (calculated using INTERGROWTH-21st, version 1.3.5) [12] thus excluding potential confounders of placental change [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. The definition was prospectively defined as including women with term delivery only, as preterm delivery is typically considered pathological, whether occurring spontaneously or for iatrogenic reasons. In order to enable meaningful comparisons to be made, women in the control group were identified as meeting these criteria after delivery and subsequently gestation-matched (within a two week gestation range) to women with chronic hypertension, masked to values derived from magnetic resonance imaging, on a 2:1 basis.

No formal sample size was calculated for power of outcome variables as this was an exploratory study describing a novel technique in technology development application. This study was approved by Fulham Research Ethics Committee, REC 16/LO/1573.

2.2. Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging was performed on either a clinical Philips 3T Achieva (60 cm bore) or a Philips 1.5T Ingenia (with a wider 70 cm bore). Parameters were kept constant between women with chronic hypertension and the control group. Women underwent magnetic resonance imaging on up to two occasions, a minimum of two weeks apart and at any time point between their clinically routine anomaly ultrasound scan (at around 18–22 weeks’ gestation) and delivery. Imaging was performed supine with padding to support the lower limbs and shoulders, after an initial period of 3 min in left lateral to shift the uterus and minimise potential effects of venocaval compression. Total imaging time did not exceed 1 h, and women were offered a break of up to 30 min halfway through the scan. Maternal assessments during imaging included continuous maternal heart rate and oxygen saturation monitoring with additional blood pressure measurements every 10 min. An obstetrician or midwife was present throughout the scan. No pharmacological sedation was used.

Image based shimming was achieved using an in-house tool, based on a separately acquired B0 map, in order to reduce the effect of inhomogeneities in the magnetic field. To provide anatomical images of the fetus and placenta and their position within the uterus, a T2-weighted single shot turbo spin echo sequence with an echo time (TE) of 180 ms of the whole uterus (thereby including placenta) was acquired in coronal and sagittal planes to the mother with repetition time (TR) = 16s, SENSitivity Encoding (SENSE) = 2.5 and partial Fourier 0.625. In-plane resolution was 1.5 mm × 1.5 mm, slice thickness 2.5 mm with an overlap of 0.5 mm. The field of view was 300 × 360 x [100−200] mm (coronal) and 300 × 300 × 340 mm (sagittal) in the foot-head (FH) x right-left (RL) x anterior-posterior (AP) directions respectively.

T2* weighted imaging was acquired using a multi-echo gradient echo, echo planar imaging sequence with free breathing and took less than 1 min. For 3T scanning, 5 echo times were used: 13.81 ms/70.40 ms/127.00 ms/183.60 ms/240.2 ms, TR = 3s, SENSE = 3, halfscan = 0.6 at 3mm3 resolution with the whole placenta covered within 60 slices. For 1.5T scanning, 5 echo times were used: 11.376 ms/57.313 ms/103.249 ms/149.186 ms/195.122 ms, TR = 14s, no SENSE, no halfscan at 2.5mm3 resolution with the whole placenta covered within 90 slices. Echo times result from the chosen Echo Planar Imaging (EPI) train characteristics. The intra-echo spacing was chosen to minimise acoustic noise and the inter-echo spacing as the minimal possible spacing given chosen resolution and field of view. Data was acquired in the maternal coronal plane.

Given the methods development required during the course of this study, a diffusion prepared spin echo with subsequent gradient echoes was performed in a subset of 31 women, imaged at only 3 T, for combined diffusion-relaxometry [17]. In another subset of women, a modified inversion-recovery sequence with a global adiabatic inversion pulse and slice shuffling [17,18] was also employed with 10 inversion times to produce T1 maps.

An in-house Python script was used to produce T2*, T1 and apparent diffusion coefficient maps by fitting monoexponentially decay curves. The diffusion data were motion corrected using Advanced Normalization Tools, ANTS, a nonrigid template registration [19]. The placenta images were manually segmented by two experienced observers (AH and JH). Further processing steps calculated mean apparent diffusion coefficient values, placental T2*, and kurtosis and skew of T2* histograms, and calculation of mean T1. The acquisition and processing pipeline has been described previously and shown to have good reproducibility with a high Dice coefficient (0.86) between observers who segmented the placenta [20,21].

As part of this study, anatomical T2-weighted imaging of the fetal brain was performed in three orthogonal planes to the woman suitable for volume reconstruction and clinical reporting [22]. Fetal brain images were reported and available to the clinical team. Visual analysis of the placenta was performed and included assessment of signal intensity across the placenta and documentation of the appearance of placental lobules and septa. The signal intensity within lobules was visually assessed for granularity with high granularity defined as the presence of both high and low signal intensity within individual lobules.

Maternal venepuncture was performed as close to magnetic resonance imaging as feasible, usually on the same day. Six millilitres of blood were drawn into a bottle containing ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid, transported to the laboratory within 1 h and underwent centrifugation at 1400×g (rcf) for 10 min at 4 °C. PlGF was quantified using the Triage PlGF Test (Alere, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions while masked to both cohort and clinical outcome. The clinical team did not receive the result.

2.3. Ultrasound

Ultrasound scans were performed on the same day as magnetic resonance imaging wherever possible, or within two weeks. Women with pre-eclampsia had a clinically indicated ultrasound scan performed in line with national guidelines for management of pre-eclampsia [23]. In the control group, ultrasound scans were performed on a Philips EPIQ V7 by sonographers following a clinical protocol. Fetal measurements included biparietal diameter, head circumference, femur length and abdominal circumference which were used to derive an estimated fetal weight using the Hadlock formula [24], umbilical artery Doppler pulsatility index (PI), amniotic fluid index and maternal uterine artery pulsatility index. The presence of fetal growth restriction was established by ultrasonographic assessment using accepted international definitions [25].

2.4. Placental histology

Following delivery and where available, placentas from women in both groups (chronic hypertension and healthy pregnancies) underwent histological examination according to local protocols at the Cellular Pathology Department, St Thomas’ Hospital. Placentas were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and trimmed of both umbilical cord and membranes for placenta weight. The following areas were sampled and then embedded in paraffin: two transverse sections of the umbilical cord, one roll of membranes (including rupture site), two to three full thickness blocks of the placental parenchyma away from the placental edge (including fetal and maternal surfaces). Additional areas were sampled depending on macroscopic findings. Paraffin embedded tissue sections were then cut into four-micron sections, deparaffinized and stained with haemotoxylin and eosin prior to histological examination. A clinical report for all placentas submitted was issued, in accordance with local hospital reporting guidelines. Histological slides were then re-examined by a second experienced histopathologist (masked to first report and to clinical details aside from gestational age at delivery) specifically for features of maternal vascular malperfusion, fetal vascular malperfusion and acute chorioamnionitis; classified using guidelines from the International Placental Pathology Consensus Meeting, Amsterdam 2014 [26]. Any discrepancies between the two reporting histopathologists were re-examined (again masked to the pregnancy outcome) and a consensus opinion was reached.

2.5. Statistical methods

In uncomplicated pregnancies, gestation-adjusted reference ranges for placental mean T2* were established using the Stata command xriml, and the 10%–90% reference range established. Birthweight centiles were calculated using INTERGROWTH-21st version 1.3.5 [12]. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Results were visually assessed between groups after plotting imaging derived measures against gestational age at imaging. A two sample t-test was used to compare placental mean T2* values (z scores) between women with chronic hypertension and controls. The imaging derived values of skewness and kurtosis were transformed (a constant added and the value subsequently logged) ensuring that the skewness of the data remained the same in order to compare groups by geometric mean ratio with adjustment for gestation.

3. Results

129 women underwent placental imaging: 43 women with chronic hypertension were gestation matched to 86 controls (Table 1, Supplemental Table S1, Supplemental Fig. S1). Of these, 30 women with chronic hypertension and 70 controls were imaged on the 3T Achieva, while 13 women with chronic hypertension and 16 controls were imaged on the 1.5T Ingenia. Maternal PlGF concentrations around time of imaging were lower in women with chronic hypertension (186 pg/mL, IQR 109–321) than the control group (341 pg/mL, IQR 230–656) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics at booking and enrolment.

| Chronic hypertensive pregnancies | Control pregnancies | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of women | 43 | 86 |

| At booking | ||

| Maternal age, y, median (IQR) | 37 (34–41) | 34 (32–37) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 26 (24–30) | 23 (21–25) |

| Nulliparous | 15 (35) | 45 (52) |

| White ethnicity | 25 (58) | 75 (87) |

| Black ethnicity | 8 (19) | 4 (5) |

| Other ethnicity | 10 (23) | 7 (8) |

| Current smoking | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Quit smoking before pregnancy | 1 (2) | 4 (5) |

| Never smoked | 37 (86) | 73 (8) |

| Previous pre-eclampsia | 7 (16) | 1 (1) |

| Chronic renal disease | 6 (14) | 0 |

| Gestational diabetes | 2 (5) | 0 |

| At enrolment on day of MRI | ||

| Gestational age, wk, median (IQR) | 27.7 (23.9–32.1) | 28.9 (26.1–32.9) |

| Aspirin | 38 (88) | 7 (8) |

| Ultrasound estimated fetal weight, centile, median (IQR) | 48 (27–70) | 54 (42–68) |

| Placental Growth Factor, pg/mL, median (IQR) | 187 (109–321) | 341 (230–656) |

| Placental growth factor <100 pg/mL | 6 (14) | 6 (7) |

| Placental growth factor <12 pg/mL | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg, median (IQR) | 125 (115–133) | 108 (102–114) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg, median (IQR) | 79 (71–83) | 63 (57–74) |

| During MRI | ||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg, median of individual medians (IQR) | 112 (108–115) | 99 (95–105) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg, median of individual medians (IQR) | 69 (63–74) | 59 (55–64) |

Values given as a number (percentage) unless stated otherwise.

Four out of 43 women (9%) with chronic hypertension developed superimposed preeclampsia (Table 2, Supplemental Table S2). Nine (21%) of women with chronic hypertension delivered prematurely compared with no preterm deliveries in the control group (Table 2, Supplemental Table S2). 38 (88%) of women with chronic hypertension had a planned delivery (pre-labour caesarean section or induction of labour) compared to 32 (37%) in the control group (Table 2, Supplemental Table S2).

Table 2.

Maternal and neonatal outcomes.

| Chronic hypertensive pregnancies | Control pregnancies | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of women | 43 | 86 |

| Time from MRI to delivery, days, median (IQR) | 70 (37–96) | 84 (53–99) |

| Pre-eclampsia | 4 (9) | 0 |

| Onset of delivery | ||

| Spontaneous | 5 (12) | 55 (64) |

| Induction | 19 (44) | 20 (23) |

| Pre labour caesarean | 19 (44) | 12 (14) |

| Mode of delivery | ||

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 9 (21) | 47 (55) |

| Assisted vaginal delivery | 4 (9) | 18 (21) |

| Elective pre-labour caesarean section | 10 (23) | 10 (12) |

| Urgent caesarean section | 20 (47) | 11 (13) |

| Primary reason for induction or prelabour caesarean* | ||

| Maternal indication | 30 (74) | 15 (17) |

| Fetal indication | 8 (19) | 16 (19) |

| Delivery | ||

| Livebirth | 43 (100) | 86 (100) |

| Gestational age at delivery, weeks, median, IQR | 38.3 (37.5–38.9) | 40 (39–41) |

| Preterm birth <37/40 | 9 (21) | 0 |

| Birthweight, g, median (IQR) | 2965 (2520–3362) | 3482 (3229–3721) |

| Birthweight centile, centile, median (IQR) | 37 (16–70) | 68 (32–83) |

| Number admitted to neonatal unit for ≥ 48 h | 4 (9) | 1 (1) |

| Prematurity | 2 (5) | 0 |

| Fetal growth restriction/small for gestational age | 0 | 0 |

| Respiratory disease | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Suspected sepsis | 0 | 0 |

| Hypoglycaemia | 2 (5) | 0 |

| Placental histology findings | ||

| Number of placentae assessed | 24 | 44 |

| Placental weight, g, median (IQR) | 384 (310–467) | 474 (409–556) |

| Fetal-placental birthweight ratio, median (IQR) | 7.2 (6.0–7.9) | 7.3 (6.7–7.9) |

| Maternal vascular malperfusion features | 5 (21) | 1 (2) |

| Fetal vascular malperfusion features | 1 (4) | 0 |

| Chorioamnionitis features | 6 (25) | 25 (57) |

Values given as a number (percentage) unless stated otherwise. *Full details given in Supplementary Table 1.

68 placentas were examined after delivery (24 from women with chronic hypertension, 44 from controls) (Table 2). Five out of six placentae with maternal vascular malperfusion features on histological examination were from women with chronic hypertension (Table 2). Out of the six cases that had maternal vascular malperfusion features on histology, three had low mean T2* values and one had high skewness and kurtosis values when compared to the control group. Median interval from imaging to delivery in cases of maternal vascular malperfusion was 40 days (interquartile range 26–79).

3.1. Magnetic resonance imaging analysis

Visual analysis of placental images demonstrated that in women with chronic hypertension, appearances were more varied compared to gestation-matched controls (Fig. 1). Placental images from women with chronic hypertension appeared either appropriate for gestation or advanced for gestation showing with increased lobulation, with wider septa and more marked heterogeneity than expected for age. This was also apparent when visually assessing the T2* maps. Reflecting this visual analysis, women with chronic hypertension showed a greater range of placental mean T2* values for a given gestation compared to the control group (Fig. 2, Supplemental Fig. S2). Women with chronic hypertension had lower placental mean T2* values compared to controls (gestation adjusted z score mean = −0.830, standard deviation 1.3), that was substantially different (two sample t-test, t = 3.11, p = 0.0031).

Fig. 1.

Example T2 weighted imaging and T2* maps in coronal and sagittal planes across gestation. On the left, the control panel depicts the following from left to right: T2-weighted imaging in the coronal plane, T2-weighted imaging in the sagittal plane, T2* map in the coronal plane and T2* map in sagittal plane. On the right, the panel depicts images from women with chronic hypertension and a placental mean T2* value below the 10th centile. Within the panel from left to right, images are in the following order: T2-weighted imaging in the coronal plane, T2 weighted imaging in the sagittal plane, T2* map in the coronal plane and T2* map in sagittal plane. Within the T2* maps, darker areas represent low T2* values while brighter orange-yellow areas high T2* values.

Fig. 2.

Scatterplot of placental mean T2* at 3 T against gestational age at imaging, subdivided by birthweight centile at subsequent delivery to show Appropriate for Gestational Age (AGA) infants, and those Small for Gestational Age, divided into 3rd-10th centile, and those <3rd centile (A) in uncomplicated control group and (B) in women with chronic hypertension.

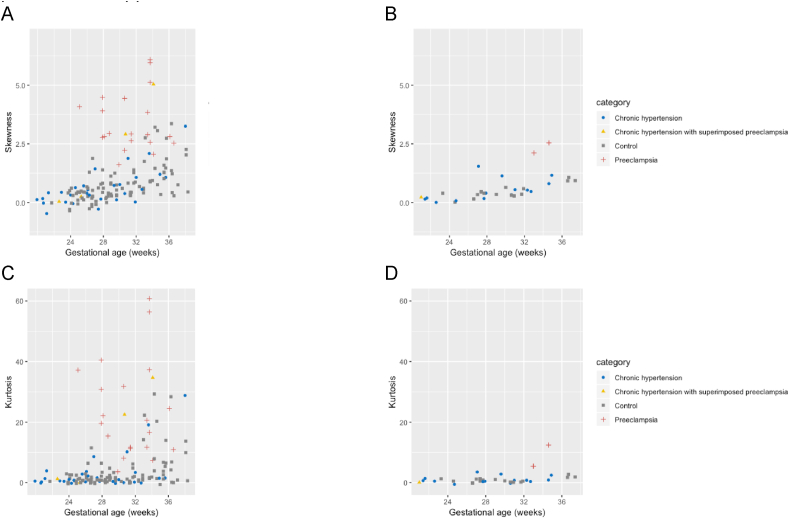

Exemplar histograms of T2* values at 27 weeks’ gestation in four different women (Fig. 3) visually illustrate further analysis of T2* histograms assessing both kurtosis and skewness. This further analysis demonstrated differences in the placenta from those chronic hypertension pregnancies with apparently normal mean T2* placental values. For example, when compared to a T2* placental histogram from a control pregnancy (Fig. 3A) a lower kurtosis value in the placental signal intensity frequency distribution in a pregnancy with chronic hypertension is demonstrated, despite a mean T2* appropriate for gestational age (Fig. 3B). A lower mean T2* value corresponds to a left shift in the histogram (for example, in a woman with chronic hypertension (Fig. 3C). A left shift and higher skewness value (asymmetrical frequency distribution) is seen in a woman with preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension (Fig. 3D). Both skewness and kurtosis increased with advancing gestational age at imaging (Fig. 4); visual inspection showed that some women with chronic hypertension who developed superimposed pre-eclampsia had higher skewness and kurtosis values, compared to the remaining group with chronic hypertension, the majority of whom had values within the range of the control group. The women who developed superimposed preeclampsia on a background of chronic hypertension with skewness and kurtosis values within the range of the control group, delivered at term and of normal birthweight centile. For the presentation of results of skewness and kurtosis values, we have included an additional dataset of women with preeclampsia imaged at 3T in whom we have previously reported enrolment and pregnancy outcome characteristics [27]. The new histogram derived measures of skewness and kurtosis in this group of women with preeclampsia have not previously been reported. Enrolment and pregnancy outcomes of preeclampsia pregnancies imaged at 1.5T are provided in Supplemental Table S1 and Supplemental Table S2. When comparing between groups, there was no significant difference in skewness and kurtosis values between the chronic hypertension and control group (geometric mean ratio for skewness values = 0.82, 95% CI 0.67–1.01, geometric mean ratio for kurtosis values = 0.83, 95% CI 0.58–1.19). In contrast, women with preeclampsia had higher skewness and kurtosis values compared to controls (geometric mean ratio for skewness values = 3.15, 95% CI 2.39–4.15, geometric mean ratio for kurtosis values = 7.55, 95% CI 4.53–12.58). Actual placental mean T2*, skewness and kurtosis values are provided in Supplemental Table S3.

Fig. 3.

Illustrative histogram plot of T2* values at the same gestation (27 weeks' gestation) for one woman from each of the following groups (A) the control group (B) with chronic hypertension (CHTN) and normal placental mean T2* (C) with chronic hypertension and a placental mean T2* less than the 10th centile for gestation (D) CHTN participant who developed superimposed preeclampsia (PE).

Fig. 4.

Scatterplot of histogram derived measures of (A) skewness at 3T imaging, (B) skewness at 1.5T imaging, (C) kurtosis at 3T imaging and (D) kurtosis at 1.5T imaging against gestational age at scan with i) chronic hypertension ii) chronic hypertension at enrolment who subsequently developed superimposed preeclampsia after imaging iii) controls iv) preeclampsia at enrolment. For the presentation of results, we have included an additional dataset of women with preeclampsia imaged at 3T in whom we have previously reported enrolment and pregnancy outcome characteristics [27] and women with preeclampsia imaged at 1.5T in whom enrolment and pregnancy outcome characteristics are provided in Supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

In our subsample, placental apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) appeared to decline with advancing gestational age (Supplemental Fig. S3A). There was a positive correlation between ADC values and placental mean T2* values (Supplemental Fig. S3B). Placental mean T1 also declined with advancing gestational age (Supplemental Fig. S3C) and positively correlated with mean ADC values (Supplemental Fig. S3D). Trends in mean ADC values were consistent with data acquired during the methods development required during the course of this study (Supplemental Fig. S4).

4. Discussion

This case-control study has used magnetic resonance imaging at both 1.5 and 3 T to acquire T2, T2*, T1 and diffusion weighted imaging of the placenta in a group of women with chronic hypertension and shown a varied visual appearance on images in women with chronic hypertension when compared to controls. T2* values showed expected decrease with gestation in the control group (consistent with previously reported values in the literature (Sorenson et al., 2019) but a more variable spread of values in chronic hypertension. T2* histogram derived measures of kurtosis and skewness showed an increase in values with advancing gestation and the majority of women with chronic hypertension had values within the range of the control group. We found no direct correlation between placental histology findings and imaging derived measures. However, these results may be a feature of the time interval between imaging and delivery.

A strength of this study is that we have quantitively measured the described visual variation in placental appearance using mean T2* and further probed the characteristics of T2* values across the whole placenta using histogram derived measures of kurtosis and skewness and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient. These histogram derived measures are independent of magnetic field strength and therefore enable comparisons between groups regardless of the strength of MR scanner used to acquire data. Imaging in women with chronic hypertension has not (to our knowledge) been previously published. The extent of the diverse phenotype seen was therefore uncertain prior to conducting the study.

To further investigate both normal and abnormal placental phenotypes we have used in-house optimised sequences combining diffusion-relaxometry which provides regionally matched diffusion and T2* values in a reasonably fast scan time compared to conventional sequences. In the integrated approach, the imaging sequence contains a spin-echo with subsequent gradient echoes. Given T2* values vary with gestation and pregnancy complications, a sequence which can disentangle the molecular motion secondary to T2* values and intrinsic diffusion properties of the placenta is of great benefit when elucidating the underlying mechanisms of placental dysfunction. Secondly, motion correction was achieved post image acquisition. Given diffusion measures the thermal microscopic translational motion of water molecules, any measures which can minimise the effect of macroscopic motion are beneficial. Motion correction was successfully performed on all women in whom the combined diffusion-relaxometry sequence was deployed.

The heterogeneity amongst the chronic hypertensive group with regards to enrolment characteristics and pregnancy outcome reflect the clinical context in which these women are managed. This study was inclusive in order to lay the foundation for assessment as a potential tool in a clinical setting. The use of scanners at two magnetic field strengths (1.5 T and 3 T) further increases clinical applicability given their use in different hospital centres and the wider bore of our 1.5 T scanner enabled women of a greater abdominal girth and body mass index to be imaged. The addition of combined diffusion relaxometry examination protocols in women enrolled later in the study reflects the imaging methods development required during the course of this study. This study additionally demonstrated that imaging was feasible and acceptable in a large cohort of women across a range of gestations amongst a group which included those with chronic hypertension. Given the wider clinical phenotype of disease in contrast to women with preeclampsia (whereby there is a close interval between imaging and delivery by clinical nature and a clear placental phenotype previously demonstrated by our group (Ho et al., 2020), a clear placental phenotype remains challenging in women with chronic hypertension.

To our knowledge, there are no studies investigating the use of placental magnetic resonance imaging in women with chronic hypertension. Our group have previously described a placental phenotype in women with preterm preeclampsia, where T2-weighted imaging demonstrated advanced lobulation, varied lobule sizes, high granularity and substantial areas of low signal intensity with reduced entire placental mean T2* values for gestational age [27]. Other studies have focussed on the prediction of fetal growth restriction [28] and low mean T2* values have been demonstrated to occur in pregnancies with fetal growth restriction [29]. The use of T2* histogram derived measures of kurtosis and skewness has not been widely described. There is a paucity of literature regarding the use of placental diffusivity measures in hypertensive disorders as studies have mainly focused on pregnancies complicated by fetal growth restriction. Reduced placental ADC values in growth restriction have implicated a phenotype with restricted diffusion [30,31]. Our results showing a decline in ADC values in the third trimester in uncomplicated pregnancies are consistent with two known studies investigating the relationship between ADC values and gestational age [9,32]. However, there is a paucity in the literature for these measures at 3 T. The use of a novel combined diffusion-relaxometry sequence has enabled the addition of T2* to ADC values, examined simultaneously for a more accurate evaluation of placental properties. Furthermore, these novel sequences have been deployed in pregnancies complicated by hypertension; a group not extensively studied before using this technique.

The placental phenotype in women with chronic hypertension has an overlap with women of uncomplicated pregnancies, as demonstrated by mean T2*, kurtosis, skew and ADC values. However, when more parameters were employed subtle differences found between groups e.g. with histogram measures in the presence of same T2* value. This potentially reflects the heterogeneity in pregnancy outcomes amongst women with chronic hypertension. The greater range of placental mean T2* values for a given gestation within this group accompanied by skewness, kurtosis and ADC values within the normal range suggests a more complex interaction between the placenta and maternal response determining the development of adverse pregnancy outcomes such as superimposed preeclampsia. This contrasts with a clearer placental phenotype in women with preterm preeclampsia, previously described by our group [27]. The skewness, kurtosis and mean T2* values within the normal range in women with chronic hypertension who develop superimposed preeclampsia may be due to the long interval between imaging and preeclampsia diagnosis as these women developed preeclampsia at term. We evaluated new measures (skewness and kurtosis) in women with preeclampsia, that had not previously been reported to enable the chronic hypertensive group results to be interpreted in context. In addition, the number of women with chronic hypertension who subsequently developed superimposed preeclampsia were small in our study (four women). Given the limitations of using a case-control study in predicting pregnancy outcomes, we have been cautious in our interpretation; however, anticipate that future prospective studies will further address this.

A reduction in mean T2* and ADC values with advancing gestation in the third trimester perhaps reflects parenchymal changes after initial placental angiogenesis in the first and second trimester, followed by villous maturation, calcium deposition and fibrosis in the third trimester. Decreased T2* and ADC values amongst women with preeclampsia may reflect the histological features seen with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. These include maternal vascular malperfusion lesions such as increased syncytial knots, villous agglutination, increase intervillous fibrin deposition and villous infarcts.

Given the exploratory nature of the study, describing a novel technique in technology development application, visual assessment of results was carried out. This is (to our knowledge) the first study of magnetic resonance imaging in women with pregnancies complicated by chronic hypertension and therefore anticipate that this study will usefully define further research directions. A larger data set imaging woman with uncomplicated pregnancies would enable robust derivation of normal ranges over gestation for comparison against groups of interest. Future work may focus on deriving gestation adjusted normal ranges for each imaging measure. This would assist in calculating multiple of median (MoM) values in order for group comparisons. Although this is one of the largest magnetic resonance imaging studies in the literature, we have been cautious in direct group comparisons to avoid being potentially misleading. Typically, a minimum of over 200 measurements (Saffer et al., 2013) equally spaced across 20–40 weeks’ gestational age are required to robustly derive normal ranges. In addition, women enrolled as control pregnancies would require confirmation of a normal pregnancy outcome and a non-linear trend of imaging derived values with gestational age would further complicate this.

Placental imaging offers a window into the placental contribution and mechanisms potentially accounting for the heterogeneity in pregnancy outcomes of women with chronic hypertension. Future work may focus on evaluating the interaction between the placental dysfunction and the varied maternal response that may elucidate development of the varying adverse pregnancy outcomes. In this study, the interval between imaging and delivery was variable and therefore further large studies would be beneficial in investigating the clinical applicability of magnetic resonance imaging as a potential tool to monitor high risk women and aid clinical management decisions around optimal timing of delivery. Further technological developments may enable certain steps in processing to be automated through machine learning algorithms and increase opportunities for implementation in clinical practice.

Contributors

AH, JH, JVH, MR and LCC were involved in study conception, design, data acquisition and analysis. PS and PTS were involved in data analysis. LJ, LM, MA, AM, SG and LS contributed to data acquisition. All co-authors made substantial contribution to data interpretation, manuscript drafting, revision and have all approved the final version.

Sources of funding

This work is funded by the NIH Human Placenta Project grant 1U01HD087202-01, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research Professorship (Chappell; RP-2014-05-019), Tommy's (Registered charity no. 1060508) and Holbeck Charitable Trust with support from the Wellcome EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering at Kings College London (WT 203148/Z/16/Z) and by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. PTS is partly funded by King's Health Partners Institute of Women and Children's Health, Tommy's (Registered charity no. 1060508) and by ARC South London (NIHR). JH is funded by the Wellcome Trust through a Sir Henry Wellcome Fellowship (201,374).

Declaration of competing interest

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK National Health Service, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the women who participated in the study, their midwives and obstetricians involved in study recruitment. We thank Alexia Egloff for clinical reporting and the research radiographers.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2020.12.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Seely E.W., Ecker J. Circulation. 2014;129:1254–1261. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bramham K., Parnell B., Nelson-Piercy C., Seed P.T., Poston L., Chappell L.C. BMJ. 2014;348 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2301. g2301–g2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sibai B.M., Lindheimer M., Hauth J., Caritis S., VanDorsten P., Klebanoff M., MacPherson C., Landon M., Miodovnik M., Paul R. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:667–671. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovo M., Bar J., Schreiber L., Shargorodsky M. The relationship between hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and placental maternal and fetal vascular circulation. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2017;11 doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2017.09.001. 724-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bustamante Helfrich B., Chilukuri N., He H., Cerda S.R., Hong X., Wang G., Pearson C., Burd I., Wang X. Placenta. 2017;52:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine R.J., Lim K.-H., Schisterman E.F., Sachs B.P., Sibai B.M., Karumanchi S.A. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004:12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Redman C.W.G., Sargent I.L. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2010;63:534–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slator P.J., Hutter J., Palombo M., Jackson L.H., Ho A., Panagiotaki E., Chappell L.C., Rutherford M.A., Hajnal J.V., Alexander D.C. Magn. Reson. Med. 2019:27733. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27733. mrm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siauve N., Hayot P.H., Deloison B., Chalouhi G.E., Alison M., Balvay D., Bussières L., Clément O., Salomon L.J. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. Off. J. Eur. Assoc. Perinat. Med. Fed. Asia Ocean. Perinat. Soc. Int. Soc. Perinat. Obstet. 2019;32:293–300. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1378334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingram E., Morris D., Naish J., Myers J., Johnstone E. Radiology. 2017;285:953–960. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017162385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown M.A., Magee L.A., Kenny L.C., Karumanchi S.A., McCarthy F.P., Saito S., Hall D.R., Warren C.E., Adoyi G., Ishaku S. International society for the study of hypertension in pregnancy (ISSHP) Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018;13:291–310. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villar J., Ismail L.C., Victora C.G., Ohuma E.O., Bertino E., Altman D.G., Lambert A., Papageorghiou A.T., Carvalho M., Jaffer Y.A., Gravett M.G., Purwar M., Frederick I.O., Noble A.J., Pang R., Barros F.C., Chumlea C., Bhutta Z.A., Kennedy S.H. Lancet. 2014;384:857–868. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60932-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desoye G., Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:S120–S126. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Llurba E., Sanchez O., Ferrer Q., Nicolaides K.H., Ruiz A., Dominguez C., Sanchez-de-Toledo J., Garcia-Garcia B., Soro G., Arevalo S., Goya M., Suy A., Perez-Hoyos S., Alijotas-Reig J., Carreras E., Cabero L. Eur. Heart J. 2014;35:701–707. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salafia C.M., Minior V.K., Pezzullo J.C., Popek E.J., Rosenkrantz T.S., Vintzileos A.M. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995;173:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salafia C.M., Vogel C.A., Vintzileos A.M., Bantham K.F., Pezzullo J., Silberman L. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1991;165:934–938. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90443-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutter J., Slator P.J., Christiaens D., Teixeira R.P.A.G., Roberts T., Jackson L., Price A.N., Malik S., Hajnal J.V. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:15138. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33463-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ordidge R.J., Gibbs P., Chapman B., Stehling M.K., Mansfield P. Magn. Reson. Med. 1990;16:238–245. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910160205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.B.B. Avants, N. Tustison, H. Johnson, (n.d.) 41.

- 20.Hutter J., Slator P.J., Jackson L., Gomes A.D.S., Ho A., Story L., O'Muircheartaigh J., Teixeira R.P.A.G., Chappell L.C., Alexander D.C., Rutherford M.A., Hajnal J.V. Magn. Reson. Med. 2019;81:1191–1204. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutter J., Jackson L., Ho A., Pietsch M., Story L., Chappell L.C., Hajnal J.V., Rutherford M. Wellcome Open Res. 2019;4:166. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Shuzhou, Xue Hui, Glover A., Rutherford M., Rueckert D., Hajnal J.V. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 2007;26:967–980. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2007.895456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hadlock F.P., Harrist R.B., Sharman R.S., Deter R.L., Park S.K. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1985;151:333–337. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordijn S.J., Beune I.M., Thilaganathan B., Papageorghiou A., Baschat A.A., Baker P.N., Silver R.M., Wynia K., Ganzevoort W. Ultrasound obstet. Gynecol. 2016;48:333–339. doi: 10.1002/uog.15884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redline R.W. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;213:S21–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho A.E.P., Hutter J., Jackson L.H., Seed P.T., McCabe L., Al-Adnani M., Marnerides A., George S., Story L., Hajnal J.V., Rutherford M.A., Chappell L.C. T2* placental magnetic resonance imaging in preterm PPreeclampsia: an observational cohort study. Hypertension. 2020;75 doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.14701. 1523-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poulsen S.S., Sinding M., Hansen D.N., Peters D.A., Frøkjær J.B., Sørensen A. Placenta. 2019;78:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinding M., Peters D.A., Frøkjær J.B., Christiansen O.B., Petersen A., Uldbjerg N., Sørensen A. Ultrasound obstet. Gynecol. 2016;47:748–754. doi: 10.1002/uog.14917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Javor D., Nasel C., Schweim T., Dekan S., Chalubinski K., Prayer D. Placenta. 2013;34:676–680. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonel H.M., Stolz B., Diedrichsen L., Frei K., Saar B., Tutschek B., Raio L., Surbek D., Srivastav S., Nelle M., Slotboom J., Wiest R. Radiology. 2010;257:810–819. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10092283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Capuani S., Guerreri M., Antonelli A., Bernardo S., Porpora M.G., Giancotti A., Catalano C., Manganaro L. Placenta. 2017;58:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.