Abstract

The role of particulate matter (PM) in health problems including cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and pneumonia is becoming increasingly clear. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, major components of PM, bind to aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhRs) and promote the expression of CYP1A1 through the AhR pathway in keratinocytes. Activation of AhRs in skin cells is associated with cell differentiation in keratinocytes and inflammation, resulting in dermatological lesions. Oleanolic acid, a natural component of L. lucidum, also has anti-inflammation, anticancer, and antioxidant characteristics. Previously, we found that PM10 induced the AhR signaling pathway and autophagy process in keratinocytes. Here, we investigated the effects of oleanolic acid on PM10-induced skin aging. We observed that oleanolic acid inhibits PM10-induced CYP1A1 and decreases the increase of tumor necrosis factor–alpha and interleukin 6 induced by PM10. A supernatant derived from keratinocytes cotreated with oleanolic acid and PM10 inhibited the release of matrix metalloproteinase 1 in dermal fibroblasts. Also, the AhR-mediated autophagy disruption was recovered by oleanolic acid. Thus, oleanolic acid may be a potential treatment for addressing PM10-induced skin aging.

Keywords: PM, AhR, Oleanolic acid, TNF-α MMP-1, Autophagy

INTRODUCTION

Recently, the health effects of particulate matter (PM) from the atmosphere are growing as a critical issue in Asia. PM are divided by diameter size—for example, PM10 (diameter<10 μm), PM2.5 (diameter<2.5 μm), and PM0.1 (diameter<0.1 μm). PM10 includes all types of PM. Generally, PM consists of particle carbon cores, ions, metal, and organic compounds (Folinsbee, 1993; Li et al., 2017). A previous study suggested that PM2.5 induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, mitochondrial swelling, autophagy, apoptosis, and inflammation in a HaCaT cell line (Piao et al., 2018). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), major components of PM, cause serious diseases such as lung cancer, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular (CVD) diseases, and pulmonary emphysema (Brook et al., 2004; Hamra et al., 2015; Fiorito et al., 2018).

Aryl hydrocarbon receptors (AhRs) bind to molecular complexes including Hsp90, XAP2, and p23 in cytosol. The AhR group is a basic helix–loop–helix PER/ARNT/SIM family of transcription factors and is regarded as regulators of cell morphology and homeostasis (Shimizu et al., 2000; Omiecinski et al., 2011). PAHs act as a ligand of AhRs in cells. After PAHs are bound to AhRs, this complex enters the nucleus and heterodimerizes with ARNT/HIF1β. The AhR–ARNT complex binds to xenobiotic responsive elements located upstream of target genes (e.g., cytochromes P450 such as CYP1A1) (Hankinson, 1995). The AhR–ARNT complex is dissociated and the AhRs are moved to the cytosol, where a proteasomal degradation process occurs (Davarinos and Pollenz, 1999). A previous study reported the roles of AhRs in cell differentiation and in mediating the harmful effects of environmental contaminants such as benzo(a)pyrene (Van Den Bogaard et al., 2015). Especially, AhRs play roles in pathophysiology effects such as inflammation, dermatological lesions, cancer promotion, and liver fibrosis (Larigot et al., 2018). Previously, we identified that PM10 including PAHs activates the AhR signaling pathway in keratinocytes (Jang et al., 2019).

Exposure to PM results in systemic immune responses due to increasing proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and IL-8 in lung epithelial cells (Hetland et al., 2005). In keratinocytes, PM10 activates AhRs and secretes tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-α) and pro-inflammatory cytokine such as IL-6 (Tsuji et al., 2011). TNF-α is responsible for immunity and induces necrotic or apoptotic cell death (Idriss and Naismith, 2000). Previous studies have shown that inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 induce matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), collagenases, causing skin wrinkles by degrading fibrillar collagen (Bae et al., 2008).

Autophagy is a catabolic process characterized by self-digestion through the degradation of cellular constituents to form nutrients and maintain cellular homeostasis (Azad et al., 2009). During the autophagy process, the autophagosome, which involves microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3-II (LC3-II) and p62, engulfs macromolecules and organelles and fuses with lysosome for degradation. However, recent studies have reported that an increase in autophagy causes autophagic cell death in macrophages (Su et al., 2017). Other research suggested that the disruption of autophagy—that is, the suppression of autophagic degradation—causes neuronal diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease (Liu et al., 2015). Dermatologically, the disruption of autophagy such as the accumulation of autophagosomes in dermal fibroblasts increases the MMP-1 content and leads to skin aging (Tashiro et al., 2014). In a previous study, we confirmed that PM10 treatment increases LC3-II and p62 in HaCaT and alpha-naphthoflavone (α-NF), which is an AhR antagonist that decreases LC3-II and p62 through the inactivation of AhRs (Jang et al., 2019).

Ligustrum lucidum is a plant distributed across hot and humid climates such as South Korea, India, and China (Chen et al., 2017). In China, L. lucidum is used as a treatment for liver and kidney conditions (Qiu et al., 2018). Many pharmacological studies have suggested L. lucidum shows effective antitumor, anti-inflammation, immunoregulatory, and antiosteoporosis activities (An et al., 2007; Dong et al., 2012; Ravipati et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012). Oleanolic acid, which is a naturally occurring triterpenoid with the chemical name 3 β-hydroxy-olea-12-en-28-oic acid, is found in Olea europaea and L. lucidum (Perez-Camino and Cert, 1999; Feng et al., 2011). Oleanolic acid possesses a variety of pharmacological activities such as hepatoprotective, wound-healing, anti-inflammation, anticancer, and antioxidant effects (Pollier and Goossens, 2012). However, the effects of oleanolic acid and L. lucidum on PM10-induced skin aging are still unknown. Thus, in this study, we investigated the effects of oleanolic acid and two types of L. lucidum extract on PM10-induced skin aging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental material

Fine Dust (PM10-like) (ERM®-EZ100) was purchased from the European Reference Materials (ERM) (St. Louis, MO, USA). Fine Dust particles are composed of the size range of 10 μm (x ≤10 μm). α-naphthoflavone (α-NF) which is known as an inhibitor of AhR and used for positive control, and oleanolic acid were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Preparation of plant extract and fraction

The Ligustrum lucidum was purchased from Jeju Biodiversity Institute (Jeju, Korea). Ligustrum lucidum (200 g) was submerged in 70% ethanol for 72 h at room temperature to retrieve extracts. The extract was then filtered with 3 μm paper and concentrated using an evaporator (Rotovapor R-100, Buchi, Flawil, Switzerland). The resulting extract (13.134 g), Ligustrum lucidum ethanol extract (LL), was resuspended in water and partitioned sequentially with n-hexane, ethyl acetate, and water, followed by in vacuum evaporation to yield the ethyl acetate fraction (2.08 g).

Chromatographic analysis

HPLC-DAD analyses were carried out using an Agilent 1260 Inifinity (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). HPLC columns were silica-based C18 Agilent Zorbax Elclipse Plus (250 mm×4.6 mm, 5 μm) (Agilent), column temperature of 30°C, injection volume of 20 μL, and wavelength of 203 nm was used.

The mobile phase was acetonitrile, water with 0.1% phosphoric acid under an isocratic system.

Cell culture

Human immortalized keratinocyte cell line (HaCaT) was obtained from Amore Pacific Company (Yongin, Korea). Human dermal fibroblasts cell line (HDF) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (VA, USA). Cells were cultured in DMEM (Welgene, Gyeongsan, Korea) medium supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine serum (FBS), and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Cell viability

Cells were incubated at a density of 1×104 cells/well in 96-well plates. After 24 h at 37°C, the media was replaced with PM diluted to the appropriate concentrations for 24 h. Next, the cells were washed with DPBS and EZ-cytox reagent (Daeil Lab Service, Seoul, Korea) was added, and cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The absorbance was measured using a microplate reader (Tecan, Mannedorf, Switzerland) at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Sample treatment

HaCaT was pre-treated with different concentrations of LL (20 μg/mL), LL-EA (2.5, 5, 10 μg/mL) or oleanolic acid (2.5, 5, 10 μg/mL) for 6 h, and after that PM10 (50 μg/mL) was treated.

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

For RT-PCR, 1ul each of cDNA and respective primers were added to HiPi PCR premix (ELPIS BIO, Daejeon, Korea). The synthesized cDNA was amplified with the following primers : β–actin sense 5’-GGCATCGTGATGGACTCCG-3’; antisense 5’-GCTGGAA-GGTGGACAGCGA-3’; CYP1A1 sense 5’-TCTTTCTCTTCCTGGCTATC-3’; antisense 5’-CTGTCTCTTCCCTTCACTCT-3’; TNF-α sense 5’-GGCAGTCAGATCATCTTCTCGAA-3’; antisense 5’-GAAGGCCTAAGGTCCACTTGTGT-3’. The finished PCR products were visualized by electrophoresis separation on 2% agarose gels with staining RedSafe™ Nucleic Acid staining Solution (Intron Bio, Seongnam, Korea).

Fibroblast supernatant media preparation

HaCaT cells were exposed to PM10 with or without oleanolic acid for 30 min and changed fresh media for 24 h. HaCaT cultured supernatant transferred to HDF cells for 30 min and changed fresh media for 48 h. The HDF cultured supernatant were used for analyzing secreted MMP-1 level.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The supernatant media and cells were collected after treatment. The test for the MMP-1 or the IL-6 were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The protein content of cell was quantified using a BCA protein Assay Reagent Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Western blot assay

Cells were seeded in six-well plates in DMEM. One day later, after washing in DPBS, the cells were treated with diluted sample in DMEM with FBS 2% for pre-determined amounts of time. Following treatment, the cells were washed in DPBS and lysed in RIPA buffer (Noble Bio, Hwaseong, Korea) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC, Sigma Aldrich) and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, Sigma Aldrich) for 30 min at 4°C. The lysate was subjected to centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 20 min and the resulting supernatant was stored on ice for immediate use or –20°C for longer term storage. The protein content of the supernatant was quantified using a BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit (Thermo Scientific) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Equal amounts of protein were separated by NuPAGE™ 12% Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Antibodies against β-actin (1:20,000, Sigma Aldrich), p62 (1:1,000, Abcam) were used at 4°C for 24 h. Blots were then incubated with Horse-radish peroxidase conjugated anti-mouse (1:20,000, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) or anti-rabbit (1:5,000, Bethyl, Montgomery, TX, USA) secondary antibodies as appropriate at 4°C for 2 h. Blots were visualized by adding a chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific) and imaged with a FlourChemE imager (HNS Bio, Seoul, Korea).

Statistical analysis

All the in vitro data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by independent t-test. A value of *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Optimization of the chromatographic conditions

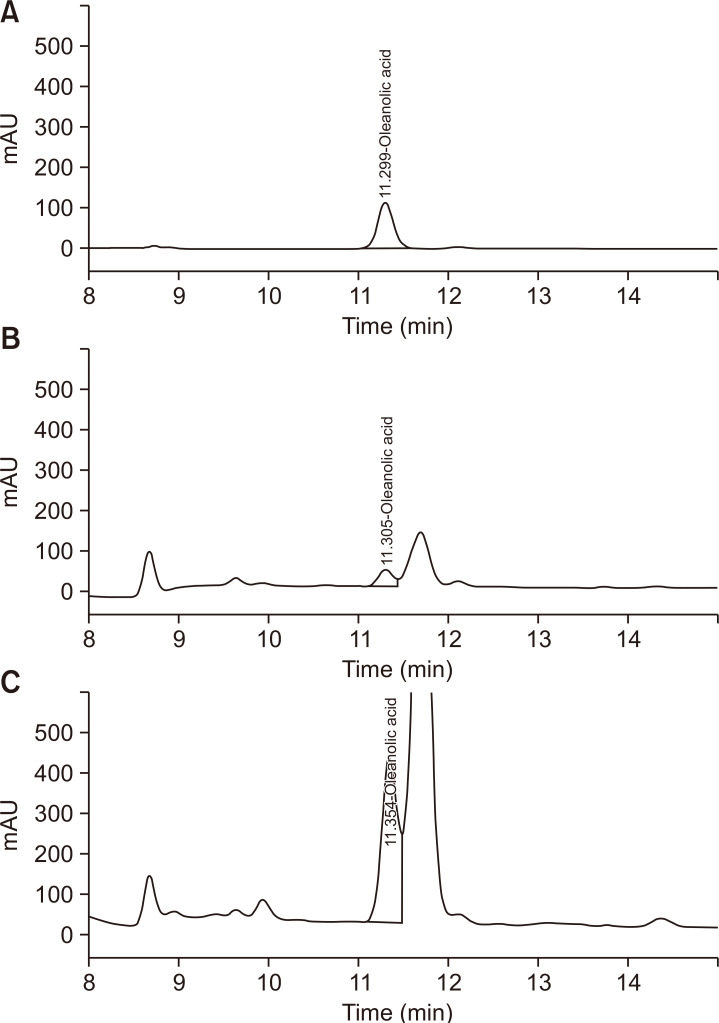

The ratio acetonitrile and water containing phosphoric acid as the mobile phase, column temperature of 30°C, and wavelength of 203 nm. Under the proposed analytical conditions, baseline resolution was obtained for all the analyses. Chromatograms of the standards and sample solutions are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

High-performance liquid chromatogram-PDA analysis. (A) Ligustrum lucidum ethanol extract (LL), (B) oleanolic acid and (C) L. lucidum ethyl acetate extract (LL-EA).

Ligustrum lucidum ethanol extract (LL), L. lucidum ethyl acetate extract (LL-EA), and oleanolic acid inhibited PM10-induced activation of AhRs in keratinocytes

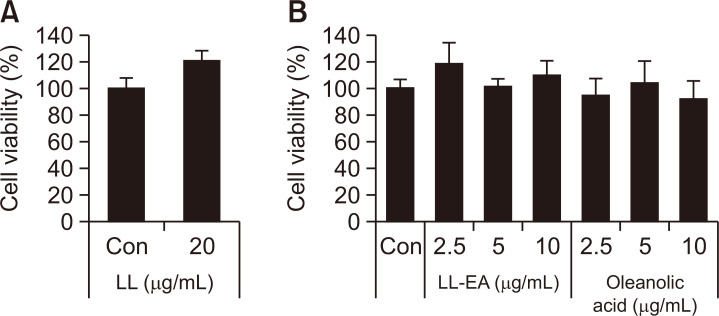

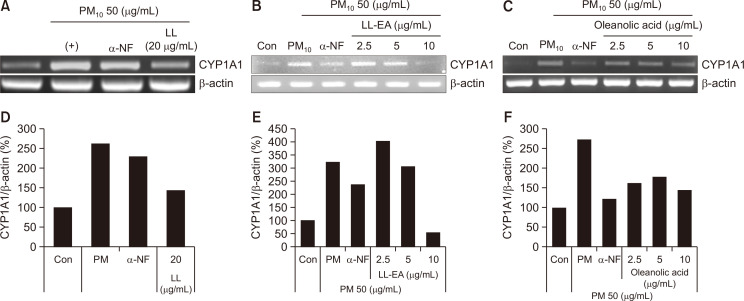

To determine the cytotoxic effects of LL, LL-EA, and oleanolic acid, HaCaT cells were treated with indicated concentrations of LL for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 2, no cytotoxic effects were observed. To determine whether LL inhibits the PM10-induced activation of AhRs in keratinocytes, we analyzed the CYP1A1 messenger RNA (mRNA) level by RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 3A, 3D, PM10 increased the CYP1A1 mRNA level, although this increase was reduced by LL (20 μg/mL). Also, α-NF, inhibitor of AhR, decreased the CYP1A1 mRNA level. Separately, to determine whether LL-EA and oleanolic acid inhibit the activation of AhRs in keratinocytes, we analyzed the CYP1A1 mRNA level by RT-PCR. PM10 increased the CYP1A1 mRNA level, which was decreased by LL-EA (2.5 μg/mL, 5 μg/mL, and 10 μg/mL) (Fig. 3B, 3E) and oleanolic acid (2.5 μg/mL, 5 μg/mL, and 10 μg/mL) (Fig. 3C, 3F). These results suggested that LL-EA inhibits the PM10-induced activation of AhRs more effectively at a lower concentration when compared with LL.

Fig. 2.

Effects of LL, LL-EA and oleanolic acid on keratinocyte viability. (A) HaCaT was treated with LL for 24 h. (B) HaCaT was treated with LL-EA and oleanolic acid for 24 h. Cell viability was assessed using the Ez-Cytox assay and measured at 450 nm. Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three determinations (n=3).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of PM10-induced CYP1A1 by LL, LL-EA and oleanolic acid in keratinocytes. (A) HaCaT was pre-treated with different concentrations of LL 20 μg/mL for 6 h, and after that PM10 (50 μg/mL) was treated for 3 h and analyzed by RT-PCR. (B) HaCaT was pre-treated with different concentrations of LL-EA (2.5, 5, 10 μg/mL) for 6 h, and after that PM10 (50 μg/mL) was treated for 3 h and analyzed by RT-PCR. (C) HaCaT was pre-treated with different concentrations of oleanolic acid (2.5, 5, 10 μg/mL) for 6 h, and and after that PM10 (50 μg/mL) was treated for 3 h and analyzed by RT-PCR. Histograms of quantitated mRNA expression were showed in (D-F).

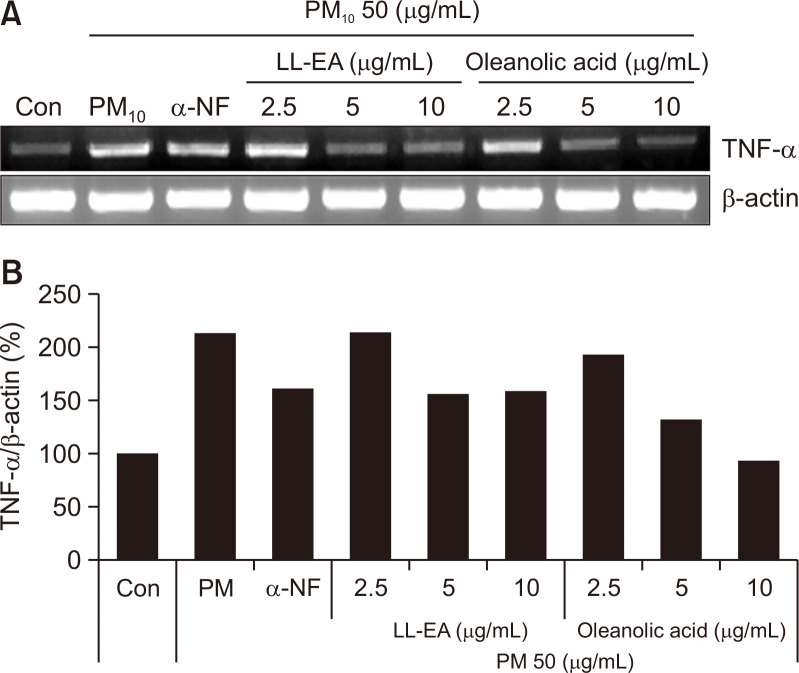

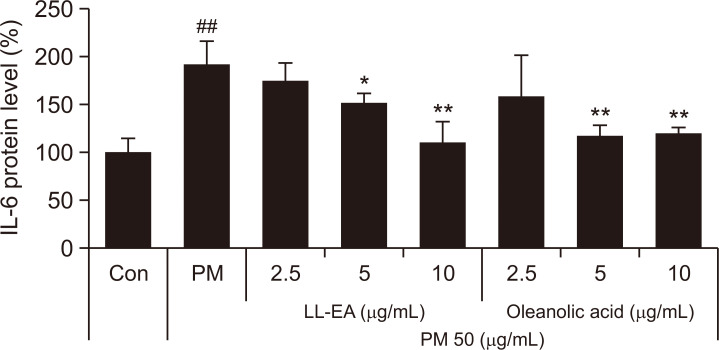

LL-EA and oleanolic acid downregulate heightened TNF-α and IL-6 levels increased by the PM10-induced activation of AhRs

To determine the effects of LL-EA and oleanolic acid on TNF-α, we analyzed the TNF-α mRNA level by RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 4, PM10 increased the TNF-α mRNA level and this increase was thereafter reduced by LL-EA (2.5 μg/mL, 5 μg/mL, and 10 μg/mL) and oleanolic acid (2.5 μg/mL, 5 μg/mL, and 10 μg/mL). To determine the effects of LL-EA and oleanolic acid on IL-6, we analyzed the IL-6 protein level by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The PM10 treatment group showed increased IL-6 content in keratinocytes, which was decreased by LL-EA and oleanolic acid. Similarly, α-NF decreased the IL-6 level (Fig. 5). These results suggested that PM10-induced TNF-α and IL-6 levels could be decreased by LL-EA or oleanolic acid.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of PM10-induced TNF-α by LL-EA and oleanolic acid in keratinocytes. (A) HaCaT was pre-treated with different concentrations of LL-EA (2.5, 5, 10 μg/mL) or oleanolic acid (2.5, 5, 10 μg/mL) for 6 h, and after that PM10 (50 μg/mL) was treated for 18 h and analyzed by RT-PCR. Histograms of quantitated mRNA expression were showed in (B).

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of PM10-induced IL-6 by LL-EA and oleanolic acid in keratinocytes. HaCaT was pre-treated with different concentrations of LL-EA (2.5, 5, 10 μg/mL) or oleanolic acid (2.5, 5, 10 μg/mL) for 6 h, and after that PM10 (50 μg/mL) was treated for 24 h. Supernatants were used to analyze Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three determinations (n=3). *p<0.05, **p<0.01 versus PM10 treatment group; ##p<0.01 versus control group.

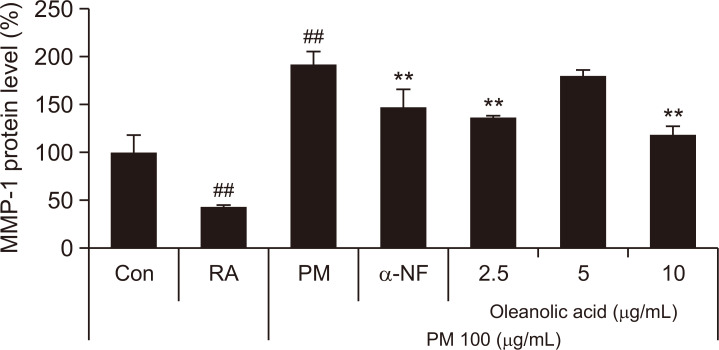

Supernatant derived from PM10-treated keratinocytes stimulated MMP-1 protein in dermal fibroblasts

We performed an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to reveal that the PM10-induced MMP-1 protein level is decreased by oleanolic acid in dermal fibroblasts. As shown in Fig. 6, PM10 treatment supernatant increased MMP-1 content in fibroblasts, which was decreased by oleanolic acid treatment supernatant. Therefore, treatment by oleanolic acid in keratinocytes can inhibit the PM10-induced MMP-1 protein level in dermal fibroblasts.

Fig. 6.

Regulation of MMP-1 in dermal fibroblast by supernatant derived from keratinocytes. HaCaT was pre-treated with different concentrations of oleanolic acid (2.5, 5, 10 μg/mL) for 24 h, and co-treated with oleanolic acid and PM10 (100 μg/mL) for 30 min. After treatment, fresh media were changed and incubated for 24 h. HDFs were treated with the supernatant derived from HaCaT for 30 min. After treatment, fresh media were changed and incubated for 48 h. Supernatants derived from HDFs were used to analyze Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Values are presented as the mean ± SD of three determinations (n=3). The MMP-1 level of control was 93 ng/mL. **p<0.01 versus PM10 treatment group; ##p<0.01 versus control group.

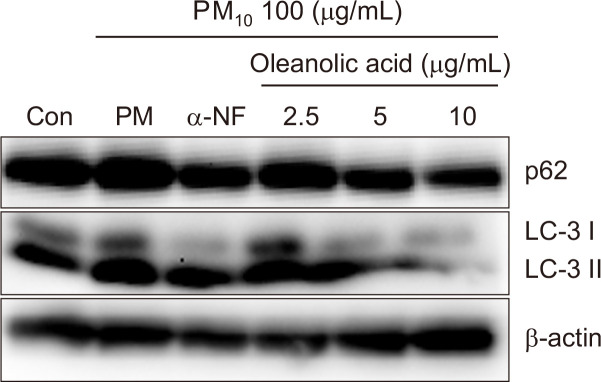

Oleanolic acid decreased the autophagy process caused by the activation of AhR in keratinocytes

Previous research showed that PM10 increases LC3-II and p62 proteins via the activation of AhRs in keratinocytes (Jang et al., 2019). To examine the effect of oleanolic acid in the PM10-induced autophagy process, we investigated the protein expression of LC3-II and p62 by western blotting. In our study, LC3-II and p62 expression were decreased by oleanolic acid or α-NF without LC3-II or p62 accumulation (Fig. 7). This result suggests that oleanolic acid could decrease the PM10-induced autophagy process without autophagy disruption.

Fig. 7.

Oleanolic acid decrease PM10-induced autophagy process in keratinocyte. HaCaT were pre-treated with different concentrations of oleanolic acid (2.5, 5, 10 μg/mL) for 6h, and after that PM10 (100 μg/mL) was treated for 24 h and analyzed by Western blot. β-actin was used as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

In a previous study, we demonstrated that AhRs are activated by PM10 in keratinocytes, which increases the expression of the CYP1A1 gene. In our experiments, we reviewed whether oleanolic acid, LL and LL-EA, and oleanolic acid can inhibit the activation of AhRs. We used ethyl acetate extraction to increase the content of oleanolic acid, which is major component of L. lucidum. As shown in Fig 3, LL-EA decreased the CYP1A1 mRNA level at a lower concentration than that of LL. Our results suggest that oleanolic acid is the major component needed to inhibit the activation of AhRs.

TNF-α initiates nuclear factor–kappa B (NF-κB) nuclear translocation by dissociating the inhibitory protein I-kBα from NF-κB (Wong et al., 1997). When NF-κB is translocated in the nucleus, such promotes the expression of inflammatory cytokine proteins like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Hayden and Ghosh, 2008; Baker et al., 2011). Separately, NF-κB and inflammatory cytokines can induce the expression of MMPs (Sato et al., 1990; Vincenti and Brinckerhoff, 2007). Because various cytokines can affect skin aging, we analyzed TNF-α and IL-6 expression levels and found that LL-EA and oleanolic acid effectively reduced PM10-induced increases in TNF-α and IL-6 content (Fig. 4, 5).

In a recent study, a keratinocyte–fibroblast integrated culture system, which is a more suitable means by which to analyze the directional effects of skin exposure rather than the cocultured method, was used to analyze the MMP-1 protein level (Fernando et al., 2019). In the present study, we confirmed that the production of MMP-1 in fibroblasts can be influenced by supernatant derived from keratinocytes according to the keratinocyte–fibroblast integrated culture system. After we cotreated with oleanolic acid and PM10 in keratinocytes, we obtained supernatant, which might have contained various inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6. The supernatant was then applied to human dermal fibroblasts and we analyzed the MMP-1 protein level in said dermal fibroblasts. As shown in Fig. 7, oleanolic acid decreased the PM10-induced MMP-1 content. This result suggests that oleanolic acid treatment applied to keratinocytes can affect the level of PM10-induced MMP-1 protein in dermal fibroblasts.

In a previous study, we discerned that LC3-II and p62 proteins, which are essential for the formation of autophagosomes, were increased by PM10 in keratinocytes (Jang et al., 2019). Because LC3-II and p62 proteins form autophagosomes, these proteins can be evaluated as markers of the autophagy process. An increase in LC3-II paired with a decrease in p62 represents the successful induction of the autophagy process. However, an increase in LC3-II together with an increase in p62 suggests the accumulation of autophagosomes, which can cause skin aging (Itakura and Mizushima, 2010; Tashiro et al., 2014). Our results indicate that PM10-induced LC3-II and p62 protein levels were decreased by oleanolic acid, signaling the reduction of the autophagy process and autophagosome accumulation (Fig. 7). Recent studies have found that PM10-induced activation of AhRs increases cellular stressors such as reactive oxygen species (Ryu et al., 2019), which is eliminated by the autophagy process (Huang et al., 2011). However, other research contends that PM-induced autophagy promotes inflammation in A549 cells (Dai et al., 2019). In further investigations, we aim to identify the correlation between inflammation and autophagy caused by the PM-induced activation of AhRs.

In conclusion, oleanolic acid could inhibit the activation of AhRs and decrease the heightened TNF-α, IL-6, and MMP-1 levels induced by PM10. Also, oleanolic acid could protects autophagosome accumulation induced by PM10. Thus, oleanolic acid can protect the skin from PM10 exposure and reduce skin inflammation and wrinkles.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant of the Gyeonggi Technology Development Program funded by Gyeonggi Province, Republic of Korea (Grant NO: D171754).

REFERENCES

- An H. J., Jeong H. J., Um J. Y., Park Y. J., Park R. K., Kim E. C., Na H. J., Shin T. Y., Kim H. M., Hong S. H. Fructus Ligustrum lucidi inhibits inflammatory mediator release through inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB in mouse peritoneal macrophages. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2007;59:1279–1285. doi: 10.1211/jpp.59.9.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad M. B., Chen Y., Gibson S. B. Regulation of autophagy by reactive oxygen species (ROS): implications for cancer progression and treatment. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11:777–790. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae J. Y., Choi J. S., Choi Y. J., Shin S. Y., Kang S. W., Han S. J., Kang Y. H. (-)Epigallocatechin gallate hampers collagen destruction and collagenase activation in ultraviolet-B-irradiated human dermal fibroblasts: involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008;46:1298–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R. G., Hayden M. S., Ghosh S. NF-kappaB, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2011;13:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook R. D., Franklin B., Cascio W., Hong Y., Howard G., Lipsett M., Luepker R., Mittleman M., Samet J., Smith S. C., Jr, Tager I. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;109:2655–2671. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128587.30041.C8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Wang L., Li L., Zhu R., Liu H., Liu C., Ma R., Jia Q., Zhao D., Niu J., Fu M., Gao S., Zhang D. Fructus ligustri lucidi in osteoporosis: a review of its pharmacology, phytochemistry, pharmacokinetics and safety. Molecules. 2017;22:1469. doi: 10.3390/molecules22091469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai P., Shen D., Shen J., Tang Q., Xi M., Li Y., Li C. The roles of Nrf2 and autophagy in modulating inflammation mediated by TLR4 - NFkappaB in A549 cell exposed to layer house particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) Chemosphere. 2019;235:1134–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davarinos N. A., Pollenz R. S. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor imported into the nucleus following ligand binding is rapidly degraded via the cytosplasmic proteasome following nuclear export. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:28708–28715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X. L., Zhao M., Wong K. K., Che C. T., Wong M. S. Improvement of calcium balance by Fructus Ligustri Lucidi extract in mature female rats was associated with the induction of serum parathyroid hormone levels. Br. J. Nutr. 2012;108:92–101. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511005186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Au-Yeung W., Xu Y. H., Wang S. S., Zhu Q., Xiang P. Oleanolic acid from Prunella Vulgaris L. induces SPC-A-1 cell line apoptosis via regulation of Bax, Bad and Bcl-2 expression. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2011;12:403–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando I. P. S., Jayawardena T. U., Kim H. S., Vaas A., De Silva H. I. C., Nanayakkara C. M., Abeytunga D. T. U., Lee W., Ahn G., Lee D. S., Yeo I. K., Jeon Y. J. A keratinocyte and integrated fibroblast culture model for studying particulate matter-induced skin lesions and thesrapeutic intervention of fucosterol. Life Sci. 2019;233:116714. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorito G., Vlaanderen J., Polidoro S., Gulliver J., Galassi C., Ranzi A., Krogh V., Grioni S., Agnoli C., Sacerdote C., Panico S., Tsai M. Y., Probst-Hensch N., Hoek G., Herceg Z., Vermeulen R., Ghantous A., Vineis P., Naccarati A. EXPOsOMICS consortium, author. Oxidative stress and inflammation mediate the effect of air pollution on cardio- and cerebrovascular disease: a prospective study in nonsmokers. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2018;59:234–246. doi: 10.1002/em.22153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folinsbee L. J. Human health effects of air pollution. Environ. Health Perspect. 1993;100:45–56. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9310045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamra G. B., Laden F., Cohen A. J., Raaschou-Nielsen O., Brauer M., Loomis D. Lung cancer and exposure to nitrogen dioxide and traffic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015;123:1107–1112. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson O. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1995;35:307–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.001515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden M. S., Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell. 2008;132:344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetland R. B., Cassee F. R., Lag M., Refsnes M., Dybing E., Schwarze P. E. Cytokine release from alveolar macrophages exposed to ambient particulate matter: heterogeneity in relation to size, city and season. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2005;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Lam G. Y., Brumell J. H. Autophagy signaling through reactive oxygen species. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011;14:2215–2231. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idriss H. T., Naismith J. H. TNF alpha and the TNF receptor superfamily: structure-function relationship(s) Microsc. Res. Tech. 2000;50:184–195. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20000801)50:3<184::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E., Mizushima N. Characterization of autophagosome formation site by a hierarchical analysis of mammalian Atg proteins. Autophagy. 2010;6:764–776. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.6.12709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H. S., Lee J. E., Myung C. H., Park J. I., Jo C. S., Hwang J. S. Particulate matter-induced Aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates autophagy in keratinocytes. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul) 2019;27:570–576. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2019.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larigot L., Juricek L., Dairou J., Coumoul X. AhR signaling pathways and regulatory functions. Biochim. Open. 2018;7:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopen.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Kang Z., Jiang S., Zhao J., Yan S., Xu F., Xu J. Effects of ambient fine particles PM2.5 on human HaCaT cells. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017;14:72. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14010072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Wang Y., Zhao S., Zhang J., Wu Y., Zeng S. Imidazole inhibits autophagy flux by blocking autophagic degradation and triggers apoptosis via increasing FoxO3a-Bim expression. Int. J. Oncol. 2015;46:721–731. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omiecinski C. J., Vanden Heuvel J. P., Perdew G. H., Peters J. M. Xenobiotic metabolism, disposition, and regulation by receptors: from biochemical phenomenon to predictors of major toxicities. Toxicol. Sci. 2011;120 Suppl 1:S49–S75. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Camino M. C., Cert A. Quantitative determination of hydroxy pentacyclic triterpene acids in vegetable oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999;47:1558–1562. doi: 10.1021/jf980881h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao M. J., Ahn M. J., Kang K. A., Ryu Y. S., Hyun Y. J., Shilnikova K., Zhen A. X., Jeong J. W., Choi Y. H., Kang H. K., Koh Y. S., Hyun J. W. Particulate matter 2.5 damages skin cells by inducing oxidative stress, subcellular organelle dysfunction, and apoptosis. Arch. Toxicol. 2018;92:2077–2091. doi: 10.1007/s00204-018-2197-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollier J., Goossens A. Oleanolic acid. Phytochemistry. 2012;77:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z. C., Zhao X. X., Wu Q. C., Fu J. W., Dai Y., Wong M. S., Yao X. S. New secoiridoids from the fruits of Ligustrum lucidum. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2018;20:431–438. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2018.1454438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravipati A. S., Zhang L., Koyyalamudi S. R., Jeong S. C., Reddy N., Bartlett J., Smith P. T., Shanmugam K., Munch G., Wu M. J., Satyanarayanan M., Vysetti B. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of selected Chinese medicinal plants and their relation with antioxidant content. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012;12:173. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu Y. S., Kang K. A., Piao M. J., Ahn M. J., Yi J. M., Bossis G., Hyun Y. M., Park C. O., Hyun J. W. Particulate matter-induced senescence of skin keratinocytes involves oxidative stress-dependent epigenetic modifications. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019;51:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0305-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Ito A., Mori Y. Interleukin 6 enhances the production of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP) but not that of matrix metalloproteinases by human fibroblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990;170:824–829. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(90)92165-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y., Nakatsuru Y., Ichinose M., Takahashi Y., Kume H., Mimura J., Fujii-Kuriyama Y., Ishikawa T. Benzo[a]pyrene carcinogenicity is lost in mice lacking the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:779–782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su R., Jin X., Zhang W., Li Z., Liu X., Ren J. Particulate matter exposure induces the autophagy of macrophages via oxidative stress-mediated PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Chemosphere. 2017;167:444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro K., Shishido M., Fujimoto K., Hirota Y., Yo K., Gomi T., Tanaka Y. Age-related disruption of autophagy in dermal fibroblasts modulates extracellular matrix components. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;443:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji G., Takahara M., Uchi H., Takeuchi S., Mitoma C., Moroi Y., Furue M. An environmental contaminant, benzo(a)pyrene, induces oxidative stress-mediated interleukin-8 production in human keratinocytes via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling pathway. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2011;62:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bogaard E. H., Podolsky M. A., Smits J. P., Cui X., John C., Gowda K., Desai D., Amin S. G., Schalkwijk J., Perdew G. H., Glick A. B. Genetic and pharmacological analysis identifies a physiological role for the AHR in epidermal differentiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2015;135:1320–1328. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincenti M. P., Brinckerhoff C. E. Signal transduction and cell-type specific regulation of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression: can MMPs be good for you? J. Cell. Physiol. 2007;213:355–364. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Shan A., Liu T., Zhang C., Zhang Z. In vitro immunomodulatory effects of an oleanolic acid-enriched extract of Ligustrum lucidum fruit (Ligustrum lucidum supercritical CO2 extract) on piglet immunocytes. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2012;14:758–763. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong H. R., Ryan M., Wispe J. R. Stress response decreases NF-kappaB nuclear translocation and increases I-kappaBalpha expression in A549 cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:2423–2428. doi: 10.1172/JCI119425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]