Abstract

This study compares the prevalence of disability and sociodemographic differences among children using 5 different disability definitions.

Accurate identification of children with disabilities is clearly a priority in multiple contexts, including measurement of health care inequities, programmatic planning, and addressing resource allocation. Yet the definitions of disability used in research, clinical, and policy-making settings vary substantially by how disability is conceptualized.1 There is a paucity of information regarding how prevalence estimates compare by disability definition and how these definitions may be inadvertently biased in their inclusion or exclusion of specific groups of children. In this study, we aimed to compare the prevalence of disability and sociodemographic differences among children using 5 different disability definitions.

Methods

We pooled National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) 2016 to 2018 samples and operationalized 5 commonly used definitions of disability that varied in complexity from single questions in the survey to those using multiple different health and functioning indicators (Figure).2,3,4,5,6 Because the publicly available NSCH contains no identifying information about participants, this study was exempt of consent by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board. Because this was a secondary data analysis, patient consent was not needed. Prevalence estimates and corresponding 95% CIs were reported. Analyses were performed using Stata, version 15 (StataCorp) with consideration of the complex survey design, weights, and income imputation for missing income data (15.3%-18.6%). Covariates with more than 3% missing data included the child’s race/ethnicity (6.2%) and metropolitan status (32% owing to suppression for confidentiality).

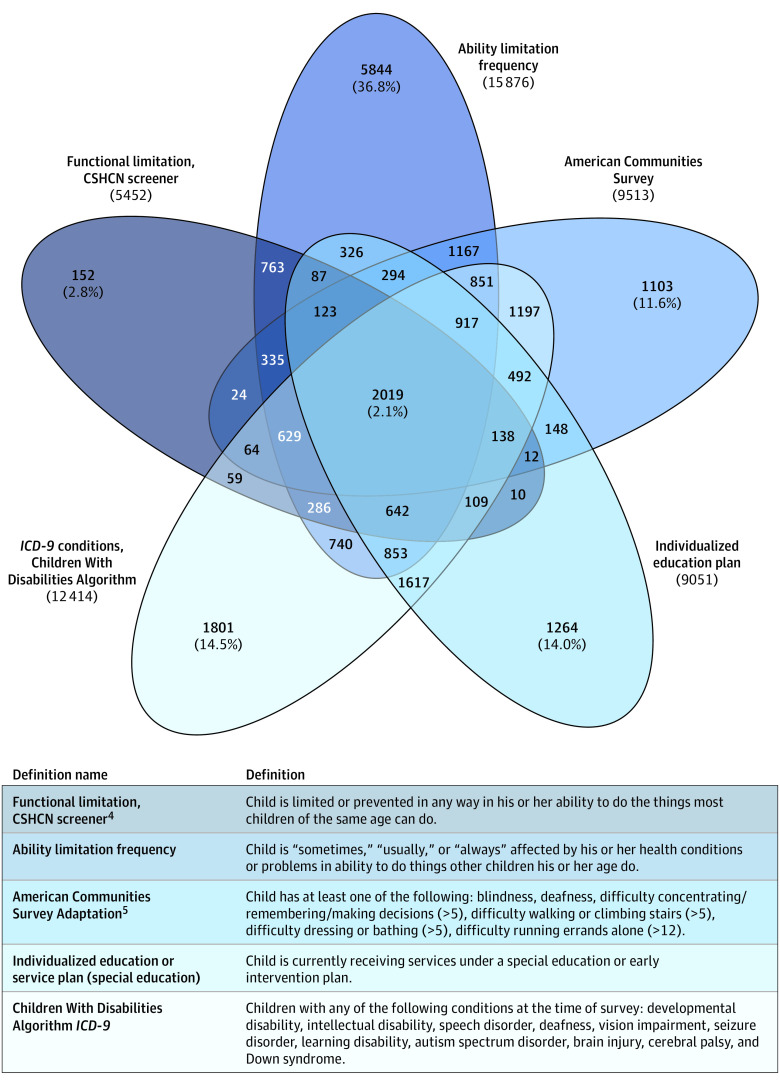

Figure. Overlap of Five Definitions of Disability From the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH).

Numbers shown are from the pooled 2016 to 2018 NSCH sample. Percentages in the figure are the percentage of unique children in the sample identified by a specific definition who were not identified by any other definition. The 5 definitions are shown in the Figure. Figure areas are not proportional to scale. Diagram created with InteractiVenn. CSHCN indicates Children with Special Health Care Needs; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision.

Results

The prevalence of disability among children ages 0 to 17 years in the NSCH in the 2016 to 2018 period ranged from 4.9% (95% CI, 4.6%-5.3%) to 14.0% (95% CI, 13.6%-14.5%) (Table), representing between 3.5 and 10.6 million children nationally. A definition based on the functional limitation item on the Children With Special Health Care Needs (CSHCN) Screener captured the smallest group of children with disabilities (4.9%) but also identified the highest proportion of children in fair/poor health (14.8%; 95% CI, 12.2%-17.4% vs 1.6%; 95% CI, 1.4%-1.8% of all children).4 Conversely, defining disability based on the frequency that a child’s abilities were limited in relation to peers (sometimes/usually/always) yielded the largest group of children with disabilities (14.0%). The American Communities Survey definition captured fewer children ages 0 to 5 years than the other definitions. Household income was inversely proportional to disability for all 5 definitions. In general, disability was overrepresented among older children, children raised by single mothers, and children of Black race/ethnicity, although there was variability in the percentage distributions. Children with disabilities were also more likely to have a multitude (≥3) of adverse childhood experiences and to have public or public/private insurance coverage.

Table. Demographics Differences Among Children Ages 0 to 17 Years Using 5 Distinct Definitions of Disability, 2016-2018 National Survey of Children's Healtha.

| Characteristics | Population, % (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ability limitation frequency | ICD-9 conditions (disabilities algorithm) | American Communities Survey | Individualized education plan | Functional limitation (CSHCN screener) | All children | |

| Overall (prevalence) | 14.0 (13.6-14.5) | 12.4 (11.9-12.9) | 9.2 (8.8-9.7) | 8.3 (7.9-8.7) | 4.9 (4.6-5.3) | NA |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 57.7 (55.1-60.3) | 62.3 (59.2-65.4) | 58.3 (54.9-61.7) | 66.9 (63.1-70.7) | 63.7 (58.4-69.0) | 51.1 (50.2-52.0) |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 0-5 | 19.0 (17.4-20.7) | 22.2 (20.2-24.2) | 6.2 (4.9-7.6) | 17.6 (15.8-19.5) | 21.7 (18.8-24.6) | 32.2 (31.5-33.0) |

| 6-11 | 38.4 (36.1-40.6) | 40.7 (38.0-43.4) | 44.5 (41.2-47.7) | 43.1 (39.6-46.6) | 37.9 (33.7-42.0) | 33.8 (33.1-34.6) |

| 12-17 | 42.6 (40.5-44.7) | 37.1 (34.7-39.4) | 49.3 (46.1-52.5) | 39.3 (36.7-41.9) | 40.4 (36.2-44.6) | 33.9 (33.2-34.6) |

| Race/ethnicityb | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 54.6 (52.7-56.4) | 51.6 (49.5-53.7) | 49.2 (46.9-51.4) | 53.3 (50.9-55.7) | 48.7 (45.9-51.5) | 53.8 (53.1-54.4) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 17.6 (15.7-19.5) | 16.5 (14.7-18.3) | 17.9 (15.6-20.2) | 18.3 (15.9-20.7) | 19.5 (15.8-23.2) | 13.8 (13.3-14.4) |

| Hispanic | 23.4 (21.0-25.8) | 28.6 (25.4-31.8) | 29.4 (25.7-33.1) | 24.6 (21.1-28.0) | 27.7 (22.7-32.7) | 26.2 (25.2-27.2) |

| Asian | 2.9 (2.3-3.6) | 2.3 (1.8-2.8) | 2.2 (1.7-2.8) | 2.5 (1.9-3.0) | 2.7 (2.0-3.5) | 4.9 (4.6-5.2) |

| ≥3 Adverse childhood experiencesc | 23.2 (21.5-25.0) | 19.8 (18.0-21.6) | 26.5 (24.2-28.8) | 19.5 (17.3-21.7) | 22.8 (19.8-25.8) | 10.0 (9.5-10.4) |

| General health fair or poor | 8.0 (6.8-9.2) | 6.4 (5.3-7.6) | 9.2 (7.5-10.9) | 5.6 (4.5-6.7) | 14.8 (12.2-17.4) | 1.6 (1.4-1.8) |

| Public insurance | 40.5 (37.8-43.2) | 42.7 (39.4-45.9) | 47.6 (43.8-51.5) | 40.9 (37.1-44.6) | 45.6 (40.4-50.8) | 31.2 (30.3-32.1) |

| Single mother | 23.7 (21.9-25.6) | 21.6 (19.8-23.4) | 24.5 (22.3-26.7) | 21.7 (19.6-23.8) | 24.2 (21.2-27.3) | 16.2 (15.6-16.7) |

| Combined family income, % FPL | ||||||

| <100 | 26.6 (24.3-28.9) | 27.4 (24.8-30.0) | 30.1 (27.1-33.2) | 25.7 (22.7-28.7) | 28.4 (24.1-32.6) | 20.6 (19.9-21.4) |

| 100-199 | 23.1 (21.3-24.9) | 25.4 (23.0-27.8) | 26.6 (23.8-29.4) | 24.3 (21.6-27.0) | 26.7 (22.7-30.7) | 22.0 (21.3-22.7) |

| 200-399 | 25.2 (23.8-26.7) | 24.2 (22.6-25.9) | 23.4 (21.6-25.3) | 24.9 (23.0-26.8) | 22.4 (20.4-24.5) | 26.9 (26.3-27.5) |

| ≥400 | 25.1 (23.8-26.4) | 23.0 (21.6-24.3) | 19.8 (18.5-21.2) | 25.0 (23.4-26.7) | 22.5 (20.3-24.7) | 30.5 (30.0-31.0) |

| Non-metropolitan place of residence | 12.6 (11.7-13.5) | 13.2 (12.1-14.2) | 14.1 (12.9-15.3) | 12.0 (10.7-13.3) | 11.4 (10.1-12.7) | 11.7 (11.3-12.0) |

Abbreviations: CSHCN, Children with Special Health Care Needs; FPL, federal poverty level; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; NSCH, National Survey of Children’s Health.

Interpretation example. Approximately 58.3% of children who met the American Communities Survey definition of disability were boys. Of all children with a disability as defined in the American Communities Survey, about 30.1% were at less than 100% of the federal poverty level.

Data were gathered from the caregiver with knowledge regarding the child's health.

A total of 9 adverse childhood experience were included in the NSCH.

About 23.5% of all children in the sample met 1 or more definitions of disability, equating to about 15.7 million children in the United States. Nearly 42.0% of children meeting any definition met only 1 definition and 8.7% of children meeting any definition met all 5 definitions of disability (2.1% of children in the overall sample, representing about 1.2 million children). About 36.8% of children meeting the sometimes/usually/always limited in abilities definition did not meet any other definition of disability, compared with just 2.8% of children meeting the functional limitation definition from the CSHCN screener. In total, 13.7% of children in the sample met 2 or more disability definitions. The 2 definitions with the least overlap were the special education and the American Communities Survey definitions.

Discussion

Prevalence estimates of disability among children ages 0 to 17 years vary widely based on the definition of disability. The small degree of overlap among all 5 definitions and the varied rates of capture of unique children based on definition suggest the need for caution when interpreting studies using a single definition. Yet, clear patterns emerged from all operationalized definitions of disability. There was a stepwise decrease in the prevalence of disability as income increased. Higher numbers of adverse childhood experiences were associated with higher prevalence of disability, as was Black race/ethnicity. Rurality was associated with higher disability prevalence in most operationalized definitions. This study reinforces the importance of careful consideration of the context of use when defining disability.3 For example, if the goal is to identify the largest group of children with disabilities, the activity limitation Likert scale is most appropriate. However, the specific health conditions definition may be most useful when attempting to concretely categorize children in clinical or research settings. This nationally representative cross-sectional study is limited by reports of child health by parents only. The disability definitions could capture different children when applied by other observers such as clinicians or teachers. More work is needed to understand how to optimize definitions of disability in research, clinical and policy-making settings given the marked differences in disability prevalence and significant sociodemographic differences within the population of children with disabilities based on the definition of disability used.

References

- 1.Berry JG, Hall M, Cohen E, O’Neill M, Feudtner C. Ways to identify children with medical complexity and the importance of why. J Pediatr. 2015;167(2):229-237. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.04.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Census Bureau . National Survey of Children's Health (NSCH). Accessed February 15, 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/nsch.html

- 3.Jerry L, Mashaw VPR. balancing security and opportunity: the challenge of disability income policy; final report of the Disability Policy Panel. National Academy of Social Insurance; 1996.

- 4.Bethell CD, Read D, Stein RE, Blumberg SJ, Wells N, Newacheck PW. Identifying children with special health care needs: development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(1):38-48. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United States Census Bureau . How disability data are collected from The American Community Survey. Published 2017. Updated October 17, 2017. Accessed March 5, 2020. https://www.census.gov/topics/health/disability/guidance/data-collection-acs.html

- 6.Simeonsson RJ, Leonardi M, Lollar D, Bjorck-Akesson E, Hollenweger J, Martinuzzi A. Applying the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) to measure childhood disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25(11-12):602-610. doi: 10.1080/0963828031000137117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]