This qualitative study investigates the prevalence and nature of mental health themes in popular rap music alongside changes in mental health distress and suicide risk among young people in the US and young Black/African American boys and men in particular from 1998 to 2018.

Key Points

Question

Have references to mental health in popular rap songs increased from 1998 to 2018?

Findings

A content analysis of lyrics to 125 popular rap songs sampled from 1998 to 2018 revealed significant increases in the proportion of songs with references to suicidal ideation, depression, and metaphors representing a mental health condition.

Meaning

Research is needed to explore the potential positive and negative influences these increasingly prevalent mental health references in popular rap songs may have in shaping mental health discourse and behavioral intentions of US youth.

Abstract

Importance

Rap artists are among the most recognizable celebrities in the US, serving as role models to an increasingly diverse audience of listeners. Through their lyrics, these artists have the potential to shape mental health discourse and reduce stigma.

Objective

To investigate the prevalence and nature of mental health themes in popular rap music amid a period of documented increases in mental health distress and suicide risk among young people in the US and young Black/African American male individuals in particular.

Design and Setting

Lyric sheets from the 25 most popular rap songs in the US in 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, and 2018, totaling 125 songs, were analyzed by 2 trained coders from March 1 to April 15, 2019, for references to anxiety, depression, suicide, metaphors suggesting mental health struggles, and stressors associated with mental health risk.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Mental health references were identified and categorized based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) and Mayo Clinic definitions. Stressors included issues with authorities, environmental conditions, work, and love life. Descriptive language and trend analyses were used to examine changes over time in the proportion of songs with mental health references. Stressors were analyzed for their co-occurrence with mental health references.

Results

Most of the 125 analyzed songs featured lead artists from North America (123 [98%]). Most lead artists were Black/African American male individuals (97 [78%]), and artists’ mean (SD) age was 28.2 (4.5) years. Across the sample, 35 songs (28%) referenced anxiety; 28 (22%) referenced depression; 8 (6%) referenced suicide; and 26 (21%) used a mental health metaphor. Significant increases were found from 1998 to 2018 in the proportion of songs referencing suicide (0% to 12%), depression (16% to 32%), and mental health metaphors (8% to 44%). Stressors related to environmental conditions (adjusted odds ratio, 8.1; 95% CI, 2.1-32.0) and love life (adjusted odds ratio, 4.8; 95% CI, 1.3-18.1) were most likely to co-occur with lyrics referencing mental health.

Conclusions and Relevance

References to mental health struggles have increased significantly in popular rap music from 1998 to 2018. Future research is needed to examine the potential positive and negative effects these increasingly prevalent messages may have in shaping mental health discourse and behavioral intentions for US youth.

Introduction

Psychological stress and suicide risk have significantly increased from 2008 to 2017 among people in the US aged 18 to 25 years.1 Twelve-month prevalence of major depressive episodes has significantly increased for people aged 12 to 20 years from 2005 to 2014.2 Anxiety and depression remain underdiagnosed and undertreated among young people. Anxiety affects 30% of adolescents, yet 80% of those affected never seek treatment.3 Only 50% of adolescents with depression are diagnosed before reaching adulthood.4,5 Mental health risk especially is increasing among young Black/African American male individuals (YBAAM),6 who are often disproportionately exposed to environmental, economic, and family stressors linked with depression and anxiety.7,8,9,10,11 Young Black/African American male individuals, and US adolescents generally, are among the least likely to use mental health services.12,13,14,15

Corresponding with the lack of mental health treatment among US youths, the suicide rate for people aged 15 to 24 years in the US in 2017 reached its highest point since 1960.16 Among people aged 10 to 24 years, suicide rates climbed 56% from 2007 to 2017.17 Suicide rates among Black/African American youths aged 13 to 19 years increased by 60% since 2001, and in 2017, medical treatment for suicide attempts was provided to 68 528 YBAAM aged 13 to 19 years.18

Young Black/African American male individuals constitute a significant portion of the audience for rap music, which has been suggested by some scholars as a promising intervention for at-risk youth.19,20 Rap music is one of the “most significant influences on the social development” of YBAAM.21(p27) However, by 2018, rap music had attracted the youngest US audience demographic and was considered a favorite genre among most US youths aged 16 to 24 years, crossing all socioeconomic strata and ethnicities.22 This is significant, because US youth spend almost 40 hours per week listening to music, and listening time in the US in general has risen by 36.6% from 2015 to 2017.23 Rap artists have also been found to serve as role models for their younger audiences, influencing the development of these young people’s identities.24,25

The aim of this study is to investigate the prevalence of mental health themes in popular rap music to test whether mental health references have increased amid a period of increasing mental health distress and suicide risk among US youths, including and extending beyond YBAAM. Prior research on US pop music has found significant increases over time in the presence of anger, disgust, fear, and sadness cues in US pop music lyrics of all genres.26 We do not know the extent to which mental health has been represented in popular music or rap in particular. However, rap artists have begun disclosing mental health struggles in the press, as evidenced by the 2017 headline “JAY-Z Gives Therapy a Major Co-Sign: ‘I Grew So Much From the Experience.’”27 Research shows that celebrity mental health disclosures can diminish stigma and encourage help-seeking behavior among fans,28,29,30 although positive references, such as therapy benefits, might have a different effect on listeners compared with more negative references of struggle. Herein, we examine lyrics of popular rap music for any reference to anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, and metaphors representing mental health. We also examine lyrics for co-occurring references to known mental health stressors,31,32 given that music artists will often connect with their audiences by referencing shared experiences.33

Methods

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill institutional review board follows the Common Rule definition of human subjects (HHS Regulation 45 CFR 40.102[f]). Per the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Human Research Protection Program Standard Operating Procedure 101, Section 3, effective September 9, 2019, this content analysis of publicly available popular music lyrics does not meet the definition of human subjects research. Therefore, this qualitative study did not qualify for institutional review board approval or informed consent.

Sample

We analyzed the lyrics of 125 popular rap songs sampled across 2 decades beginning in 1998, the year rap music first outsold the former top-selling genre in the US, country music.34 The Chart & Data Development department of Billboard provided proprietary data gratis, which identified the 25 highest ranked rap songs for the years 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, and 2018 on the Billboard hot rap songs year-end chart. High rankings reflect song popularity in the US for a given year. Popularity is estimated based on Nielsen Broadcast Data System radio airplay data from across more than 120 market areas in the US and Nielsen SoundScan sales data from across more than 90% of the US market.35 The 5-year increments of available data are in line with previous analyses of popular music that documented evolving styles and tastes.36

All 25 songs from each 5-year increment were analyzed, totaling 125 songs. Of the 125 songs sampled and analyzed, a total of 105 songs (84%) featured a Black/African American male artist either as the lead artist (97 [78%]) or as a guest (8 [6%]). Nearly all songs analyzed (123 [98%]) featured lead artists from North America. The mean (SD) age of the leading artist across the sample was 28.2 (4.5) years. Prominent artists captured in the sample included 50 Cent, Drake, Eminem, Kanye West, Jay-Z, and Lil’ Wayne, among others.

Codes

The following categories of mental health references were coded: anxiety and anxious thinking, depression and depressive thinking, and suicide and suicidal ideation. First, lyrics conveying negative emotional sentiment were identified based on 2019 typology by Fokkinga37 describing negative emotions, including personal provocation, agitation, repulsion, threats, desires, failings, misfortune, being overwhelmed, helplessness, lack of motivation, and general uncertainty. Relevant lyrics were further analyzed for specific reference to anxiety and anxious thinking, depression and depressive thinking, and suicide and suicidal ideation based on definitions developed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition)38 and Mayo Clinic descriptions of anxiety and depression.39,40,41 The negative emotion typology by Fokkinga37 also informed the identification of anxious and depressive thinking based on references to high-arousal and low-arousal negative affect, respectively.

We added a fourth category, mental health metaphor, to account for lyrics that lacked sufficient information or context to qualify as a specific reference to anxiety, depression, or suicidal ideation. Consistent with prior research of music lyrics, we documented metaphors to provide insight into the latent meaning and semiotic systems (ie, slang) used in popular music lyrics.35 We also coded all songs for references to stressors known to relate to mental health risk8,9,10: issues with authorities, environmental conditions, faith, family life, financial strain, love life, social ally (friend) issues, social rivals (foe or competitor), and work life. From pilot testing, societal issues were added as a coded stressor to account for references to macrolevel strain, such as the economy, war, or national events. Table 1 provides descriptions and examples of each category of mental health reference and stressor.

Table 1. Coding Category, Lyric Description, and Examples.

| Coding category | Lyric description | Example lyric |

|---|---|---|

| Mental health reference | ||

| Anxiety or anxious thinking | Worry, nervousness, or unease, often due to an imminent event or uncertain outcome | “What’s takin’ so long? I’m getting’ anxious…” |

| Depression or depressive thinking | Depression causing sadness and/or loss of interest in activities once enjoyed | “Went through deep depression when my mama passed…” |

| Metaphor | Reference to struggling with or generally lacking mental stability (asymptomatic) | “Pushed me to the edge so it ain’t my motherf*ckin’ fault…” |

| Suicide or suicidal ideation | Reference to taking own life | “Suicide if you ever try to let go…” |

| Stressor known to relate to mental health | ||

| Authority | Oppressive institution or authority figures (eg, police, landlord, justice/prison system) | “When the man wit’ the badge come…” |

| Environmental conditions | Living conditions with direct everyday effects | “Don’t get caught without one, coming from where I’m from…” |

| Faith | God or other religious or spiritual figure, or specific faith or religion | “’Cause when the Jesus pieces can’t bring me peace…” |

| Family life | Reference to family member or relation by blood (eg, children, parent, uncle, cousin) | “Like I needed my father, but he needed a needle…” |

| Financial strain | Finances or money | “Rob and I steal, not ‘cause I want to ‘cause I have to…” |

| Love life | Significant other, love interest, or sexual partner | “Can’t take back the love that I gave you…” |

| Social ally (friend) | Close friend, not romantic or blood-related | “Where your real friends at?...” |

| Social rival (foe) | Perceived social rival, foe, or enemy | “Lost my respect, you not a threat…” |

| Societal issues | Society-level issues including the economy, war, and poverty | “My heart to Japan, quake losers and survivors…” |

| Work life | Job, career, industry, work superiors, subordinates, competition, or coworkers | “This f*ckin’ industry is cutthroat…” |

Procedures

From March 1 to April 15, 2019, 2 trained coders (A.K. and M.K.R.C.) independently analyzed lyric sheets for the presence (coded 1) or absence (coded 0) of each mental health reference or stressor (Table 1) across each song. Using lyrics from rap songs outside the sample, coders were trained to identify phrases matching mental health category descriptions and use surrounding lyrics to determine whether the song should be coded as 1 for the presence of the respective coding category. A random 46% of the full sample (57 of 125 songs) was then coded independently by each coder to test interrater reliability in applying the coding categories.42 Interrater reliability was above acceptable levels for all codes, based on Gwet AC1 coefficients computed in AgreeStat, version 2015.6.43 All Gwet AC1 scores were greater than 0.90 except for coding the presence or absence of environmental conditions, which achieved a Gwet AC1 score of 0.76.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 25.0 (IBM Corporation). Frequencies were used to describe the prevalence of codes across rap songs within each sampled year. The Cochran-Armitage test for linear trends in proportions was used to examine whether proportions of songs with mental health references in each year increment approximated a relatively linear pattern of increase across time, using year as an ordinal variable. Cross-tabulations were used to describe the co-occurrence of mental health references and stressors associated with mental health risk. Unadjusted and Firth-adjusted logistic regressions were performed to examine which stressors were most likely to co-occur with the presence of mental health references. Regressions were performed only across songs with lyrics indicating negative emotion, excluding songs that mentioned stressors (eg, family, love) without also referencing negative emotion (ie, songs celebrating love). Statistical significance was assessed at a level of 2-sided P < .05.

Results

Most of the 125 analyzed songs featured lead artists from North America (123 [98%]). Most lead artists were Black/African American male individuals (97 [78%]); artists’ mean (SD) age was 28.2 (4.5) years. Across all sampled years, 94 of the 125 total songs (75%) referenced negative emotion, and 57 of the songs with negative emotion (61%) referenced mental health. Specifically, 35 of the total sample (28%) referenced anxiety, 28 (22%) referenced depression, 8 (6%) referenced suicide, and 26 (21%) used at least 1 mental health metaphor. As shown in Table 2, the proportion of sampled songs per year with a mental health reference increased significantly in a linear trend from 1998 to 2018 for all categories except anxiety or anxious thinking (eg, depression and depressive thinking, 4 of 25 [16%] in 1998 to 8 of 25 [32%] in 2018; P = .03). Mental health metaphors had the largest increase, from 2 of 25 (8%) in 1998 to 11 of 25 (44%) in 2018 (P < .001). Although the number of songs referencing suicide or suicidal ideation across the total sample was small (8 [6%]), the significant increase from 1998 to 2018 is also noteworthy (P = .02). No references to suicide or suicidal ideation existed in 1998 and 2003. In contrast, 6 of the 8 total songs found with this reference came from 2013 and 2018, representing 12% of the 25 songs sampled in each of those 2 years.

Table 2. Percentage of Songs Referencing Mental Health in Top 25 Rap Songs Within and Across Years.

| Mental health reference | No. (%) of songsa | P valueb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 125) | Within study year | ||||||

| 1998 (n = 25) | 2003 (n = 25) | 2008 (n = 25) | 2013 (n = 25) | 2018 (n = 25) | |||

| Anxiety or anxious thinking | 35 (28) | 6 (24) | 9 (36) | 5 (20) | 7 (28) | 8 (32) | .78 |

| Depression or depressive thinking | 28 (22) | 4 (16) | 3 (12) | 4 (16) | 9 (36) | 8 (32) | .03 |

| Mental health metaphor | 26 (21) | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | 5 (20) | 6 (24) | 11 (44) | <.001 |

| Suicide or suicidal ideation | 8 (6) | 0 | 0 | 2 (8) | 3 (12) | 3 (12) | .02 |

Coding categories are not mutually exclusive. A song can have references to more than 1 mental health category, thus rows and columns will not sum to 100.

Cochran-Armitage test for linear trends in proportions used to test for increases over time within mental health category.

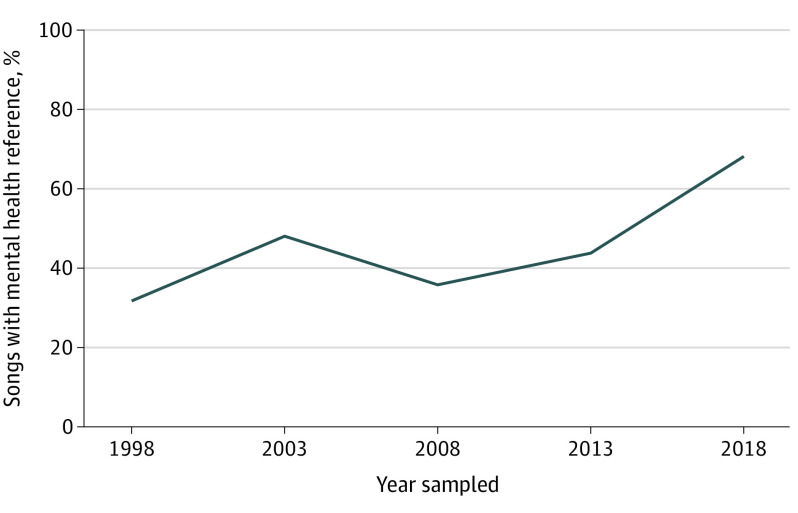

The Figure shows the combined percentage of songs within each year that referenced any of the coded mental health categories. In 1998, 32% of the 25 most popular songs referenced mental health, whereas 68% of the 25 most popular songs in 2018 had these references. The pattern shown was found to be a statistically significant linear trend based on the Cochran-Armitage test. However, as evident in the Figure, the consistent pattern of increase began in 2008.

Figure. Percentage of Songs With Any Mental Health Reference Observed Among the Top 25 Rap Songs per Sampled Year.

Mental health references include anxiety, depression, or suicide or use of a mental health metaphor per year sampled. Songs are chosen from the top 25 rap songs according to Billboard hot rap songs year-end charts for 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, and 2018. Increase across years was statistically significant according to the Cochran-Armitage test for linear trend in proportions across the sampled years (t = 4.7; P < .05).

Table 3 shows the co-occurrence of mental health references and coded stressors. Love life (38 co-occurrences), environmental conditions (42 co-occurrences), and social rivalry (59 co-occurrences) were the most common stressors across the sample. Financial strain was mentioned the least in songs referencing mental health (1 co-occurrence).

Table 3. Percentage of Songs With Co-occurring References to Mental Health and Stressors Across the Samplea.

| Type of stressor | Songs with co-occurring mental health reference, No. (%) (n = 125) | Total No. of co-occurrences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depression | Suicide | Metaphor | ||

| Social rival (foe) | 21 (17) | 10 (8) | 3 (2) | 15 (12) | 32 |

| Environmental conditions | 20 (16) | 13 (10) | 5 (4) | 16 (13) | 32 |

| Love life | 17 (14) | 16 (13) | 4 (3) | 12 (10) | 27 |

| Work life | 12 (10) | 7 (6) | 2 (2) | 6 (5) | 15 |

| Family life | 8 (6) | 8 (6) | 3 (2) | 7 (6) | 11 |

| Authority | 7 (6) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | 8 |

| Social ally (friend) | 4 (3) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1(1) | 5 |

| Faith | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 5 |

| Societal issues | 4 (3) | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (2) | 5 |

| Financial strain | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Coding categories are not mutually exclusive. A song can have references to more than 1 mental health category and/or type of stressor, thus rows and columns will not sum to 100.

Regression analyses showed a significant association between the presence of any mental health reference and the presence of references to environmental conditions (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 8.1; 95% CI, 2.1-32.0) and love life (AOR, 4.8; 95% CI, 1.3-18.1) (Table 4). Social rivalry (AOR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.1-1.3) was not significantly associated with the presence of any mental health reference. As shown in eTable 1 in the Supplement, no single stressor was associated with the presence of anxiety or anxious thinking references. As shown in eTable 2 in the Supplement, family life (AOR, 5.6; 95% CI, 1.2-26.9), faith (AOR, 15.1; 95% CI, 1.5-150.7), and social rivals (AOR, 0.2; 95% CI, 0.1-0.7) were significantly associated with the presence of depression or depressive thinking references.

Table 4. Logistic Regressions Testing Associations Between Presence of Stressors and Any Mental Health Reference in Songs Expressing Negative Emotiona.

| Stressors present | Total No. of songs | Mental health reference, No. (%) (n = 94) | Unadjustedb | Firth adjustedc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Social rival (foe) | 59 | 32 (54) | 27 (46) | 0.3 (0.1-1.2) | .09 | 0.4 (0.1-1.3) | .11 |

| Environmental conditions | 42 | 32 (76) | 10 (24) | 11.5 (2.5-51.7) | .001 | 8.1 (2.1-32.0) | .003 |

| Love life | 38 | 27 (71) | 11 (29) | 6.2 (1.4-26.8) | .01 | 4.8 (1.3-18.1) | .02 |

| Work life | 18 | 15 (83) | 3 (17) | 2.3 (0.5-11.9) | .30 | 1.9 (0.4-8.5) | .40 |

| Family life | 11 | 11 (100) | 0 | 1.4 × 109 (NC) | .99 | 23.7 (0.9-602.8) | .06 |

| Authority | 10 | 8 (80) | 2 (20) | 1.1 (0.1-8.7) | .94 | 1.1 (0.2-7.4) | .91 |

| Social ally (friend) | 7 | 5 (71) | 2 (29) | 5.0 (0.4-56.5) | .20 | 3.9 (0.4-35.6) | .23 |

| Faith | 5 | 5 (100) | 0 | 1.9 × 109 (NC) | .99 | 21.0 (0.7-683.0) | .09 |

| Societal issues | 5 | 5 (100) | 0 | 2.2 × 108 (NC) | .99 | 2.2 (0.1-75.8) | .66 |

| Financial strain | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 | 1.4 × 109 (NC) | 1.00 | 27 (0.1-1.5) | .56 |

Abbreviations: NC, not calculated; OR, odds ratio.

Analysis based on the 94 songs within the total sample that contained cues of negative emotion. Supplemental analyses were also conducted adjusting for year of song as a covariate. No changes to the reported pattern of associations were found when controlling for year. Lack of variability in family life, faith, societal issues, and financial strain (no presence of these stressors in songs without mental health references) generated exponential unadjusted ORs with 95% CIs that could not be calculated (separation phenomenon). These issues were addressed with the Firth bias adjustment.

Raw model statistics: χ2 = 41.90; P < .001; −2-log likelihood = 84.12; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.49.

Firth model statistics: χ2 = 14.84; P = .14; −2-log likelihood = 86.64; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.39.

Discussion

Our analysis of 125 of the most popular rap songs in the United States sampled from 1998 to 2018 revealed a statistically significant increase in the proportion of popular rap songs referencing suicide, depression, and metaphors suggesting mental health struggles. The proportion of rap songs that referenced mental health more than doubled in the 2 decades we examined. All of the references to suicide or suicidal ideation in our sample were found among the popular songs taken from 2013 and 2018.

This increase is important, given that rap artists serve as role models to their audience, which extends beyond YBAAM to include US young people across strata, constituting a large group with increased risk of mental health issues and underuse of mental health services.13,15,18 We cannot establish how much the increase is a response by rap artists to the increased mental health struggles experienced by audiences, although the notable increases we found in 2013 and 2018 correspond with increasing rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.1,2 We also cannot determine with our data whether these lyrical references to mental health are due to rap artists’ desires to self-disclose or to instigate discussions about mental health. The mean age of the leading artists in the sample was 28.2 years. Because rap is an autobiographical art form, the artists and younger adults may have observed and reflected national trends of distress experienced by themselves or people close to them.

One notable event that might explain the increase we observed was the 2008 release of rap album 808s & Heartbreaks by renowned rap artist Kanye West. 808s & Heartbreaks has been credited in the press for initiating a “wave of inward-looking sensitivity” among rappers.44 Rolling Stone magazine named the album one of the 40 most “groundbreaking albums of all time,” noting that its openly emotional nature “served as a new template” for budding rappers.45 The songs we analyzed from 2018 with references to mental health were from artists (ie, Drake, Post Malone, and Juice Wrld) who have acknowledged 808s & Heartbreaks as being influential to their musical style.46

The increase we found also provides insights into how mental health is framed in rap, which can inform future research on how US youth may develop their understanding of mental health risk. Our findings with respect to the mental health metaphor category are particularly informative for understanding the language used to signal mental health. We noted phrases evoking imagery of physical conflict, for example “pushed to the edge” or “fighting my demons,” that were used to suggest mental health struggles. These metaphors were found in addition to phrases such as “I’m going crazy.” The use of different types of metaphors warrants future research, as the connotations of these phrases might affect listeners differently.

The prevalence of metaphors suggests rap artists rely on this type of indirect reference to describe mental health. This reliance on metaphors might be used to discuss this difficult subject less overtly and in a way that might be viewed as more socially accepted by peers and audiences. The increased prevalence of these metaphors might also explain why references to anxiety remained consistent rather than increasing across the decades. Some metaphors suggesting high-arousal negative experiences (eg, “fighting my demons”) might have been used to suggest anxiety without explicitly noting anxiety.

Examining our findings from an ecological framework,47 rap music can be considered an exosystem, that is, a social system in which the listener does not directly function yet is an active participant. As an exosystem, mental health risk and connections made between mental health and certain stressors within this music are likely to influence mental health discourse at all levels surrounding the listener, from the overall culture to the individual’s peer group to the individual’s own psychology.48 These influences might include the provision of emotional language that can be used to articulate complex emotions and improve mental health discourse among peers.49,50 Therefore, it is important to investigate the mental health discourse in these lyrics as a first step in researching how rap music might be used to improve mental health outcomes among at-risk youth.

Placed into a larger macrosystem context, the co-occurrence we noted between mental health references and environmental conditions existed in years surrounding a December 2007 economic recession that disproportionately affected Black/African American communities and those of lower socioeconomic status. Stress caused by the recession is argued to have exacerbated already elevated rates of anxiety, depression, and domestic violence51 found in the most affected communities. Mention of financial strain was not prevalent within our sample, although materialism has traditionally been recognized as a common message within popular rap music.52 However, references to everyday living conditions and other environmental factors were the most consistent stressors mentioned in lyrics that also referenced mental health struggles, suggesting rap artists were connecting macro-level stress with mental health risk.

Limitations

The present study is limited to the top 25 songs from Billboard’s hot rap songs year-end charts from 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, and 2018 and does not fully represent the population of rap music between 1998 and 2018. We cannot address whether mental health references have existed in less popular songs or whether mental health references only exist in the most popular songs of the past decade. We also cannot address causation or motivations for the increased presence of mental health references within the sampled songs.

Like other content analyses of popular media, we also face the challenge of interpreting artists’ intended meanings behind their lyrics.35 Our conservative coding of mental health references might have resulted in an underrepresentation of the prevalence of mental health references in this music. We are also unable to ascertain how US youth interact with this music or are positively or negatively affected by its messages. We did not code for positive or negative valence of mental health references, because inferring valence from lyrics alone would not have provided coders with intentional artistic cues (ie, vocal intonation) needed to accurately interpret sentiment. Future research is therefore needed to provide a qualitative examination of the meanings and connotations of these references to better inform our understanding of how this music can improve the mental health of its listeners or how it might lead to greater risk. For example, positively framed references to mental health awareness, treatment, or support may lead to reduced stigma and increased willingness to seek treatment.53 However, negatively framed references to mental health struggles might lead to negative outcomes, including copycat behavior in which listeners model harmful behavior, such as suicide attempts, if those behaviors are described in lyrics (ie, the Werther effect).54

Conclusions

The findings of this qualitative study suggest that mental health discourse has been increasing during the past 2 decades within the most popular rap music in the US. This increase has occurred in the midst of a corresponding increase in national mental health risk,1,2,16,17 especially with respect to depressive and suicidal thoughts among YBAAM and US young people more generally, who constitute a major portion of the rap music audience. Although this study is limited in its ability to examine the effect of the variety of mental health references observed, this study supports the need for research examining the effects of rap music in efforts to reduce stigma and minimize mental health risk. As noted in a popular press article highlighting the need for more mental health discourse: “Pleas from rappers young and old are louder now than ever… When rappers open up, fans listen.”55

eTable 1. Unadjusted and Firth-Adjusted Logistic Regressions of Associations Between Presence of Stressors and Presence of Anxiety References in Songs Expressing Negative Emotion (n = 94)

eTable 2. Unadjusted and Firth-Adjusted Logistic Regressions of Associations Between Presence of Stressors and Presence of Depression References in Songs Expressing Negative Emotion (n = 94)

References

- 1.Twenge JM, Cooper AB, Joiner TE, Duffy ME, Binau SG. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128(3):185-199. doi: 10.1037/abn0000410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6):e20161878. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Child Mind Institute . Understanding anxiety in children and teens. Published 2018. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://childmind.org/our-impact/childrens-mental-health-report/2018report

- 4.Birmaher B, Brent D, Bernet W, et al. ; AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues . Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(11):1503-1526. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318145ae1c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams RE, Laraque D, Chemtob CM, Jensen PS, Boscarino JA. Does a one-day educational training session influence primary care pediatricians’ mental health practice procedures in response to a community disaster? results from the Reaching Children Initiative (RCI). Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2013;15(1):3-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francis DB. Young black men’s information seeking following celebrity depression disclosure: implications for mental health communication. J Health Commun. 2018;23(7):687-694. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2018.1506837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown TN, Williams DR, Jackson JS, et al. “Being black and feeling blue”: the mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Race Soc. 2000;2(2):117-131. doi: 10.1016/S1090-9524(00)00010-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Utsey SO. Racism and the psychological well-being of African American men. J Af Am Stud. 1997;3(1):69-87. doi: 10.1007/s12111-997-1011-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Social support, traumatic events, and depressive symptoms among African Americans. J Marriage Fam. 2005;67(3):754-766. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00167.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simons RL, Murry V, McLoyd V, Lin K-H, Cutrona C, Conger RD. Discrimination, crime, ethnic identity, and parenting as correlates of depressive symptoms among African American children: a multilevel analysis. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;14(2):371-393. doi: 10.1017/S0954579402002109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watkins DC, Green BL, Rivers BM, Rowell KL. Depression and black men: implications for future research. J Mens Health Gend. 2006;3(3):227-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jmhg.2006.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asnaani A, Richey JA, Dimaite R, Hinton DE, Hofmann SG. A cross-ethnic comparison of lifetime prevalence rates of anxiety disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(8):551-555. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ea169f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blumberg SJ, Clarke TC, Blackwell DL. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Men's Use of Mental Health Treatments. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinkewicz M, Lee R. Prevalence, comorbidity, and course of depression among Black fathers in the United States. Res Soc Work Pract. 2011;21(3):289-297. doi: 10.1177/1049731510386497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin L, Stamm K, Christidis P. Datapoint: young adults are less likely than older adults to use mental health services. Monitor Psychol. 2016;47(8):29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miron O, Yu K-H, Wilf-Miron R, Kohane IS. Suicide rates among adolescents and young adults in the United States, 2000-2017. JAMA. 2019;321(23):2362-2364. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtin SC, Heron M. Death rates due to suicide and homicide among persons aged 10–24: United States, 2000-2017. NCHS Data Brief. 2019;(352):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price JH, Khubchandani J. The changing characteristics of African-American adolescent suicides, 2001-2017. J Community Health. 2019;44(4):756-763. doi: 10.1007/s10900-019-00678-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyson EH. Hip hop therapy: an exploratory study of a rap music intervention with at-risk and delinquent youth. J Poet Ther. 2002;15(3):131-144. doi: 10.1023/A:1019795911358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Travis R. Rap music and the empowerment of today’s youth: evidence in everyday music listening, music therapy, and commercial rap music. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 2013;30:139-167. doi: 10.1007/s10560-012-0285-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elligan D. Rap therapy: a culturally sensitive approach to psychotherapy with young African American men. J Afr Am Stud. 2000;5(3):27-36. doi: 10.1007/s12111-000-1002-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Statistica. Favorite music genres among consumers in the United States as of July 2018, by age group [graph]. Published June 27, 2019. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/253915/favorite-music-genres-in-the-us/

- 23.Nielsen. Time with tunes: how technology is driving music consumption. Published November 2, 2017. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2017/time-with-tunes-how-technology-is-driving-music-consumption/

- 24.Stever GS. Fan behavior and lifespan development theory: explaining para-social and social attachment to celebrities. J Adult Dev. 2011;18(1):1-7. doi: 10.1007/s10804-010-9100-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saarikallio S. Music as a resource for agency and empowerment in identity construction. In: McFerran K, Derrington P, Saarikallio S, eds. Handbook of Music, Adolescents, and Wellbeing. Oxford University Press; 2019:89. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198808992.003.0008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Napier K, Shamir L. Quantitative sentiment analysis of lyrics in popular music. J Pop Music Stud. 2018;30(4):161-176. doi: 10.1525/jpms.2018.300411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chesman D-C. JAY-Z gives therapy a major co-sign: “I grew so much from the experience.” DJ Booth. Published November 29, 2017. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://djbooth.net/features/2017-11-29-jay-z-gives-therapy-a-major-co-sign

- 28.Hoffner CA. Responses to celebrity mental health disclosures. In: Lippert LR, Hall RD, Miller-Ott AD, Davis DC, eds. Communicating Mental Health: History, Contexts, and Perspectives. Lexington Books, Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group Inc; 2019:125. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrari A. Using celebrities in abnormal psychology as teaching tools to decrease stigma and increase help seeking. Teach Psychol. 2016;43(4):329-333. doi: 10.1177/0098628316662765 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calhoun AJ, Gold JA. “I feel like I know them”: the positive effect of celebrity self-disclosure of mental illness. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44(2):237-241. doi: 10.1007/s40596-020-01200-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGee ZT, Davis BL, Brisbane T, et al. Urban stress and mental health among African-American youth: assessing the link between exposure to violence, problem behavior, and coping strategies. J Cult Divers. 2001;8(3):94-104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rasmussen A, Aber MS, Bhana A. Adolescent coping and neighborhood violence: perceptions, exposure, and urban youths’ efforts to deal with danger. Am J Community Psychol. 2004;33(1-2):61-75. doi: 10.1023/B:AJCP.0000014319.32655.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knobloch S, Mundorf N. Communication and emotion in the context of music and music television. In: Bryant J, Roskos-Ewoldsen DR, Cantor J, eds. Communication and Emotion. Routledge; 2003:499-518. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farley CJ. Music: hip-hop nation. Time. February 8, 1999. Accessed October 27, 2020. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,19134,00.html

- 35.Primack BA, Dalton MA, Carroll MV, Agarwal AA, Fine MJ. Content analysis of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs in popular music. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(2):169-175. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curtis JM. Rock Eras: Interpretations of Music and Society, 1954-1984. Popular Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fokkinga S. Negative Emotion Typology. Dissertation. Delft University of Technology; 2019. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://emotiontypology.com

- 38.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayo Clinic. Anxiety disorders: symptoms & causes. Published May 4, 2018. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anxiety/symptoms-causes/syc-20350961

- 40.Mayo Clinic. Depression (major depressive disorder): symptoms & causes. Published February 3, 2018. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/symptoms-causes/syc-20356007

- 41.Mayo Clinic. Suicide and suicidal thoughts: symptoms & causes. Published October 18, 2018. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/suicide/symptoms-causes/syc-20378048

- 42.Riffe D, Lacy S, Fico F, Watson B. Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research. Routledge; 2019. doi: 10.4324/9780429464287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gwet KL. Handbook of Inter-rater Reliability: The Definitive Guide to Measuring the Extent of Agreement Among Raters. Advanced Analytics LLC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kot G. Album review: Drake, “Take Care.” Chicago Tribune. November 13, 2011. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://www.chicagotribune.com/chi-drake-album-review-take-care-reviewed-20111113-column.html

- 45.40 Most groundbreaking albums of all time. Rolling Stone. Published December 7, 2014. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://www.rollingstone.com/interactive/most-groundbreaking-albums-of-all-time

- 46.Whitt G. The enduring influence of Kanye West’s “808s & Heartbreak.” Genius. Published November 23, 2018. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://genius.com/a/the-enduring-influence-of-kanye-west-s-808s-heartbreak

- 47.Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development. Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychol. 2001;3(3):265-299. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0303_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheong-Clinch C. My iPod, YouTube, and our playlists: connections made in and beyond therapy. In: McFerran K, Derrington P, Saarikallio S, eds. Handbook of Music, Adolescents, and Wellbeing. Oxford University Press; 2019. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198808992.003.0021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheong-Clinch C, McFerran KS. Musical diaries: examining the daily preferred music listening of Australian young people with mental illness. J Appl Youth Stud. 2016;1(2):77. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schneider D, Harknett K, McLanahan S. Intimate partner violence in the Great Recession. Demography. 2016;53(2):471-505. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0462-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suddreth CB. Hip-Hop Dress and Identity: A Qualitative Study of Music, Materialism, and Meaning. University of North Carolina at Greensboro; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoffner CA, Cohen EL. Mental health-related outcomes of Robin Williams’ death: the role of parasocial relations and media exposure in stigma, help-seeking, and outreach. Health Commun. 2018;33(12):1573-1582. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1384348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Phillips DP. The influence of suggestion on suicide: substantive and theoretical implications of the Werther effect. Am Sociol Rev. 1974;39(3):340-354. doi: 10.2307/2094294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pearce S. Therapy is gangsta: hip-hop’s views on mental health are evolving. Pitchfork. Published September 5, 2017. Accessed October 27, 2020. https://pitchfork.com/thepitch/therapy-is-gangsta-hip-hops-views-on-mental-health-are-evolving

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Unadjusted and Firth-Adjusted Logistic Regressions of Associations Between Presence of Stressors and Presence of Anxiety References in Songs Expressing Negative Emotion (n = 94)

eTable 2. Unadjusted and Firth-Adjusted Logistic Regressions of Associations Between Presence of Stressors and Presence of Depression References in Songs Expressing Negative Emotion (n = 94)