Key Points

Question

What is the effect of a clinical pharmacist intervention on medication safety in patients who were recently discharged from the hospital and prescribed high-risk medications?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial including 361 participants, more than a quarter of patients experienced adverse drug-related incidents and nearly 1 in 5 experienced clinically important medication errors in the 45-day period following hospital discharge. A reduction in these events that was related to the intervention was not observed.

Meaning

This study did not demonstrate an improvement in medication safety with a pharmacist-directed intervention during the high-risk posthospitalization period.

Abstract

Importance

The National Action Plan for Adverse Drug Event (ADE) Prevention identified 3 high-priority, high-risk drug classes as targets for reducing the risk of drug-related injuries: anticoagulants, diabetes agents, and opioids.

Objective

To determine whether a multifaceted clinical pharmacist intervention improves medication safety for patients who are discharged from the hospital and prescribed medications within 1 or more of these high-risk drug classes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This randomized clinical trial was conducted at a large multidisciplinary group practice in Massachusetts and included patients 50 years or older who were discharged from the hospital and prescribed at least 1 high-risk medication. Participants were enrolled into the trial from June 2016 through September 2018.

Interventions

The pharmacist-directed intervention included an in-home assessment by a clinical pharmacist, evidence-based educational resources, communication with the primary care team, and telephone follow-up. Participants in the control group were provided educational materials via mail.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The study assessed 2 outcomes over a 45-day posthospital discharge period: (1) adverse drug-related incidents and (2) a subset defined as clinically important medication errors, which included preventable or ameliorable ADEs and potential ADEs (ie, medication-related errors that may not yet have caused injury to a patient, but have the potential to cause future harm if not addressed). Clinically important medication errors were the primary study outcome.

Results

There were 361 participants (mean [SD] age, 68.7 [9.3] years; 177 women [49.0%]; 319 White [88.4%] and 8 Black individuals [2.2%]). Of these, 180 (49.9%) were randomly assigned to the intervention group and 181 (50.1%) to the control group. Among all participants, 100 (27.7%) experienced 1 or more adverse drug-related incidents, and 65 (18%) experienced 1 or more clinically important medication errors. There were 81 adverse drug-related incidents identified in the intervention group and 72 in the control group. There were 44 clinically important medication errors in the intervention group and 45 in the control group. The intervention did not significantly alter the per-patient rate of adverse drug-related incidents (unadjusted incidence rate ratio, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.83-1.56) or clinically important medication errors (unadjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.65-1.49).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial, there was not an observed lower rate of adverse drug-related incidents or clinically important medication errors during the posthospitalization period that was associated with a clinical pharmacist intervention. However, there were study recruitment challenges and lower than expected numbers of events among the study population.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02781662

This randomized clinical trial examines the effect of a multifaceted clinical pharmacist intervention on medication safety for patients who are discharged from the hospital and prescribed medications within 1 or more high-risk drug classes.

Introduction

Up to one-fifth of patients experience an adverse event within weeks of leaving the hospital, and many of these events may be preventable.1,2 The risk for adverse drug events (ADEs), defined as injury due to a medication, is especially high for older patients as they transition from the inpatient to the outpatient setting.3,4

The National Action Plan for Adverse Drug Event Prevention identified 3 high-priority drug classes as key targets for reducing the risk of drug-related injuries: anticoagulants, diabetes agents (insulin and oral agents), and opioids.5 These medication classes account for the most measurable drug-related harms to patients, and many of the ADEs that are associated with these medications are considered preventable.6,7,8,9 Insulins, opioid-containing analgesics, and warfarin are among the most common medications implicated in emergency department visits and hospitalizations for ADEs,6,7 especially among older adults.8

In this study, patients recently discharged from the hospital who had been prescribed medications within 1 or more of 3 high-priority, high-risk drug classes were randomly assigned to a treatment group that received a multifaceted pharmacist-directed medication safety intervention or a control group that received medication safety educational materials via mail.

Methods

Setting

Reliant Medical Group is a multispecialty group practice located in Central Massachusetts that employs 300 physicians and 200 mid-level clinicians and provides care to more than 300 000 patients. Most patients cared for by the group are hospitalized in a 321-bed general medical and surgical hospital. Only patients of the medical group who were discharged from this hospital were eligible to participate in the study. We determined that although medication reconciliation procedures routinely happened at the time of hospital discharge, no additional medication safety interventions were systematically used, and there were no hospital-initiated efforts that extended into the outpatient setting. Patients taking warfarin were treated by an outpatient anticoagulation service of the medical group. However, connecting or reconnecting a recently discharged warfarin-treated patient with the anticoagulation service was the responsibility of the primary care clinician.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria included individuals discharged from the hospital who were patients of primary care physicians of the multispecialty medical group, prescribed at least 1 high-risk medication (anticoagulants, diabetes agents [insulin and oral agents], and/or opioids), and met at least 1 of the following additional criteria: (1) prescribed 2 or more high-risk medications, (2) low health literacy levels, (3) poor (self-reported) medication adherence, (4) had a proxy or reported having a caregiver, or (5) prescribed more than 7 different medications. Individuals were not eligible if they were (1) discharged to hospice; (2) hospitalized for a psychiatric condition; (3) discharged to a skilled nursing facility, rehabilitation hospital, or nursing home; (4) non–English speaking; or (5) incapable of providing informed consent and a proxy was not available. Initially, only patients 65 years or older were considered eligible (Supplement 1).10

We had planned to recruit 500 participants. After 8 months of lower than expected recruitment, the eligibility criteria that were relevant to patient age were relaxed from 65 years or older to 50 years or older, and the recruitment period was extended an additional year to increase the number of potentially eligible individuals to recruit. Despite those changes, we still did not achieve our recruitment goal.

Intervention

Components of the intervention included (1) in-home assessment by a clinical pharmacist (within 4 days of discharge from the hospital), (2) use of printed educational resources that were targeted to patients who were taking high-risk medications and their caregivers, (3) communication with the primary care team via the electronic health record (EHR) regarding concerning issues that were relevant to medication safety, and (4) a follow-up telephone call by the pharmacist to the patient and/or caregiver 14 days after the home visit.

The in-home visit by the study pharmacist consisted of 3 components: (1) medication review, (2) observation of medication organization and administration, and (3) in-depth patient and caregiver (if applicable) discussions about challenges to safe medication use. During the home visit, the clinical pharmacist distributed medication safety educational materials that were relevant to high-risk medications and featured medication instructions, including dose timing, dietary precautions, situational guidance (what to do when a patient misses a dose), and recommendations for when to contact the primary care clinician.

Key findings of the visit by the clinical pharmacist were communicated via the EHR immediately following the visit to alert the primary care team to safety issues that were particularly relevant to the high-risk medication categories, as well as safety issues relevant to other medications. For any urgent medication-related problems, including serious medication interactions, adverse effects, or dosage outside of the usual range, the clinical pharmacist called the primary care clinician’s office directly. Fourteen days after the home visit, the clinical pharmacist made a follow-up telephone call to discuss any problems and review and reinforce instructions that were provided during the in-home visit. Any urgent medication-related problems were again communicated with the primary care team. Control group participants were mailed print materials with information on the high-risk medications that were relevant to them.

Recruitment for the Trial

Recruitment occurred from June 2016 through September 2018. Identification of potential participants occurred through an automated system that evaluated the medication list within the hospital discharge summary. Recruitment calls for potentially eligible individuals were initiated as soon as possible following hospital discharge to enable scheduling for a pharmacist in-home visit by the fourth day postdischarge. Participants were offered a $25 gift card.

If an individual provided verbal consent, he or she was randomized so that the home visit could be scheduled immediately, but the individual was not considered enrolled until written informed consent was obtained. Written consent was sought during the study visit for the intervention group and via mail for the control group. This study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School institutional review board.

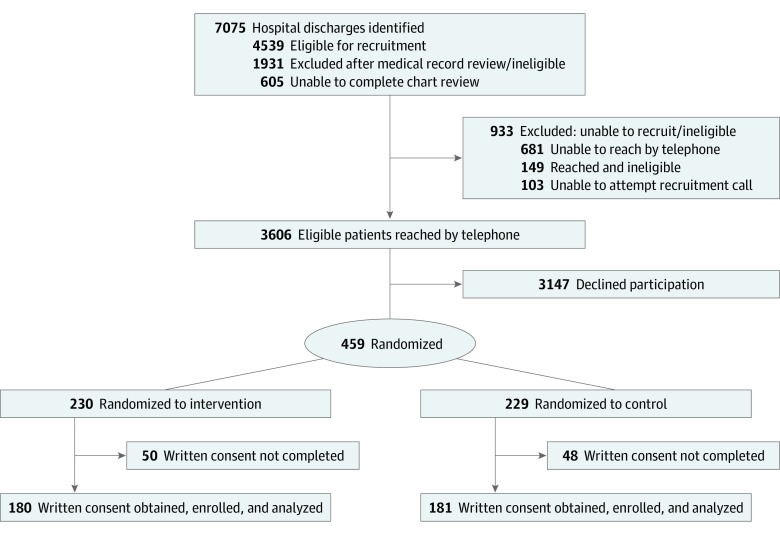

As detailed in the Figure, 7075 patients were identified as potentially eligible. Health record reviews were not conducted on 605 potentially eligible patients because of various reasons, including documentation of a “do not call for research” in the patient record, staff availability, and delays in receiving information from the hospital to assess eligibility. Study staff conducted health record reviews on 6470 patients and identified 4539 patients as eligible for recruitment calls. Of the 3755 patients reached by telephone, 3606 were found to be eligible. Of these, 459 (12.7%) gave verbal consent and were randomized (230 intervention [50.1%], 229 control [49.9%]); we used randomly permuted blocks of sizes 10 and 16, which were generated in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Randomization was stratified jointly by presence/absence of a caregiver and by the number of high-risk drug classes prescribed (1 vs 2 or more).

Figure. Adapted Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Flow Diagram.

There were 361 individuals (180 intervention [49.9%], 181 control [50.1%]) who completed written consent and were enrolled in the study. A more detailed description of recruitment and enrollment relating to our study has been previously published.11

Outcome Event Definitions

We assessed 2 outcomes: (1) adverse drug-related incidents and (2) a subset defined as clinically important medication errors,12 which included preventable or ameliorable ADEs and potential ADEs (medication-related errors that may not yet have caused injury to a patient, but have the potential to cause future harm if not addressed). Clinically important medication errors were the primary study outcome. The ADEs combined with potential ADEs comprised adverse drug-related incidents. Clinically important medication errors included preventable or ameliorable ADEs and potential ADEs. A preventable ADE was defined as a drug-related injury relating to a medication error (eg, errors in ordering, dispensing, administration, and use or monitoring). Some ADEs were not entirely preventable; however, their duration or severity could be reduced and such events were defined as ameliorable ADEs. The eFigure in Supplement 2 depicts the relationships between these different categories of outcome events. This categorization scheme is adapted from the 2007 report published by the National Academy of Sciences.13 Measured outcomes were not limited just to the high-risk medications (anticoagulants, diabetes agents, and opioids), but also included all medications.

Event Finding

Two clinical pharmacists (A.O.K. and J.L.D.) reviewed the EHRs of each patient for the 45-day period following hospital discharge; they did not participate as clinical pharmacists in the intervention. We made every effort to mask the pharmacist-investigators to the status of the patient with regard to randomization to the intervention or control arm. They reviewed outpatient encounters, telephone communications, discharge summaries, emergency department visits, and laboratory results. Each review followed a standardized procedure for searching for signals that suggested a possible drug-related incident. In addition, the pharmacist-investigators reviewed information derived from a semistructured telephone interview that was conducted with the patient and/or caregiver between 5 and 6 weeks following hospital discharge. Following the approach of Forster and colleagues,2 the interview assessed the patient’s condition since hospital discharge by using a full review of organ systems, with special attention given to symptoms that may have been relevant to medication(s) that the patient had been receiving. The patient was asked about symptom severity, timing in relation to hospitalization and treatments, and resolution.

The clinical pharmacist prepared an event summary for each possible drug-related incident, which was reviewed independently by 2 masked physician investigators (A.K, S.S, S.L.C., and J.H.G.). The physicians used a structured implicit review process according to the following criteria: whether an event was present, the type of event, the severity of the event, and whether the event was preventable. This approach has been used in numerous prior studies across various clinical settings.14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24 Physician reviewers were not aware of whether a drug-related incident being reviewed had occurred in an intervention group patient or a control patient. Adverse drug events were categorized as less serious, serious, life threatening, or fatal. Preventability was categorized as preventable, probably preventable, probably not preventable, or definitely not preventable, and results were collapsed into preventable (preventable and probably preventable) and nonpreventable (probably not preventable and definitely not preventable). When physician reviewers disagreed on the classification of an event regarding its presence, severity, or preventability, they met and reached consensus; consensus was reached in all instances in which there was initial disagreement.

Data Analysis

Possible differences between the randomized intervention and control groups across patient characteristics (eg, demographic factors, comorbidity, prescribed medications, and aspects of the index hospitalization) were investigated using t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for dichotomous and categorical variables. Race and ethnicity information was characterized solely based on information available in the EHR. The primary outcomes of interest were adverse drug-related incidents and clinically important medication errors. To evaluate the effect of the multifaceted intervention, we estimated the mean incidence rates of these outcomes within each group (intervention and control). Time denominators for the incidence rates considered the number of days that participants were available for EHR review and the telephone interview during a maximum of 45 days postdischarge, excluding days after a participant was rehospitalized, died, or disenrolled as a patient cared for by the medical group. Incidence rates were calculated as events per 100 person-days. Analysis of the primary outcomes was a direct comparison of the incidence rates for the intervention and control groups (incidence rate ratios) using multivariable analyses using Poisson binomial regression, considering the number of days each participant was followed, and adjusting for age, sex, and having visiting nurse services.

We also determined the prevalence of an emergency department visit or rehospitalization among intervention and control patients. In addition, we assessed the medication categories associated with the main study outcomes (adverse drug-related incidents and clinically important medication errors), and ADEs were characterized by type.

We had initially planned to recruit 500 participants. We estimated an expected incidence rate of the outcome of clinically important medication errors in the control group based on the findings of Kripalani and colleagues,12 which were 0.95 events per patient over a 30-day period after hospital discharge. Assuming this baseline rate, extending the observation period to 45 days, and with 0.80 power, we would be able to detect a reduction of 19% (incidence rate ratio, 0.81) with 500 participants.

Results

Study participants had a mean (SD) age of 68.7 (9.3) years, the age range was 50 to 94 years, and there were 177 women (49%). We achieved a satisfactory balance of patient characteristics across arms (Table 1); the only characteristic that was significantly different between the intervention and control arms was having visiting nurse services.

Table 1. Characteristics of Enrolled Participants.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total enrolled (N = 361) | Intervention (n = 180) | Control (n = 181) | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 68.7 (9.3) | 69.44 (9.4) | 68.03 (9.3) | .15 |

| Age category, y | .31 | |||

| 50-54 | 22 (6.1) | 9 (5.0) | 13 (7.2) | |

| 55-59 | 42 (11.6) | 24 (13.3) | 18 (9.9) | |

| 60-64 | 56 (15.5) | 22 (12.2) | 34 (18.8) | |

| 65-69 | 73 (20.2) | 34 (18.9) | 39 (21.5) | |

| 70-74 | 63 (17.5) | 33 (18.3) | 30 (16.6) | |

| 75-79 | 56 (15.5) | 28 (15.6) | 28 (15.5) | |

| ≥80 | 49 (13.6) | 30 (16.7) | 19 (10.5) | |

| Sex | .10 | |||

| Women | 177 (49.0) | 96 (53.3) | 81 (44.8) | |

| Men | 184 (51.0) | 84 (46.7) | 100 (55.3) | |

| Race | .33 | |||

| White | 319 (88.4) | 162 (90.0) | 157 (86.7) | |

| Black | 8 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) | 6 (3.3) | |

| Othera | 4 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Unknown | 30 (8.3) | 13 (7.2) | 17 (9.4) | |

| Ethnicity | .23 | |||

| Hispanic | 13 (3.6) | 8 (4.4) | 5 (2.8) | |

| Not Hispanic | 278 (77.0) | 143 (79.4) | 135 (74.6) | |

| Unknown | 70 (19.4) | 29 (16.1) | 41 (22.7) | |

| Prescribed >1 high-risk medication | 195 (54.0) | 97 (53.9) | 98 (54.1) | .96 |

| Prescribed a high-risk medication at discharge | ||||

| Anticoagulant | 184 (51.0) | 98 (54.4) | 86 (47.5) | .19 |

| Diabetes agents | 135 (37.4) | 71 (39.4) | 64 (35.4) | .42 |

| Opioid | 223 (61.8) | 105 (58.3) | 118 (65.2) | .18 |

| Prescribed a new high-risk medication at discharge | 305 (84.5) | 154 (85.6) | 151 (83.4) | .58 |

| Anticoagulant | 166 (46.0) | 88 (48.9) | 78 (43.1) | .27 |

| Diabetes agents | 112 (31.0) | 62 (34.4) | 50 (27.6) | .16 |

| Opioid | 209 (57.9) | 98 (54.4) | 111 (61.3) | .19 |

| Taking ≥7 medications of any kind | 334 (92.5) | 165 (91.7) | 169 (93.4) | .54 |

| Has caregiver | 235 (65.1) | 117 (65.0) | 118 (65.2) | .97 |

| Low health literacy level | 110 (30.5) | 61 (33.9) | 49 (27.1) | .16 |

| Has visiting nurse services | .004 | |||

| Yes | 187 (51.8) | 99 (55.0) | 88 (48.6) | |

| No | 117 (32.4) | 64 (35.6) | 53 (29.3) | |

| Unknown | 57 (15.8) | 17 (9.4) | 40 (22.1) | |

| Reason for admission | .63 | |||

| Medical | 198 (54.9) | 104 (57.8) | 94 (51.9) | |

| Surgical | 88 (24.4) | 43 (23.9) | 45 (24.9) | |

| Orthopedic | 69 (19.1) | 30 (16.7) | 39 (21.6) | |

| Medical procedure | 6 (1.7) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.7) | |

| Admitted through emergency department | 213 (59.0) | 104 (57.8) | 109 (60.2) | .64 |

| Length of stay, mean (SD), d | 2.73 (2.6) | 2.59 (2.2) | 2.87 (2.9) | .31 |

Racial category of other comprised Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native.

The clinical pharmacist reviewers identified 191 possible drug-related incidents, of which 153 (80%) were adjudicated by the physician reviewers as adverse drug-related incidents. Among all participants, 100 (27.7%) experienced 1 or more adverse drug-related incidents, and 65 (18%) experienced 1 or more clinically important medication errors. Table 2 summarizes the trial findings. There were 81 adverse drug-related incidents in the intervention group and 72 in the control group. Intervention patients contributed 7392 days of follow-up, and control patients contributed 7447 days. The incidence rate of adverse drug-related incidents in the intervention group was 1.10 per 100 person-days and 0.97 per 100 person-days in the control group. The intervention did not significantly alter the per-patient rate of adverse drug-related incidents (unadjusted incidence rate ratio, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.83-1.56). The adjusted incidence rate ratio was 0.97 (95% CI, 0.70-1.34).

Table 2. Number of Adverse Drug-Related Incidents, ADEs, and Clinically Important Medication Errors During the First 45 Days After Hospital Discharge by Treatment Assignment.

| Characteristic | Events, No.a | IRR (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Intervention | Control | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | ||||

| No. | IR | No. | IR | No. | IR | |||

| All adverse drug-related incidents | 153 | 1.03 | 81 | 1.10 | 72 | 0.97 | 1.13 (0.83-1.56) | 0.97 (0.70-1.34) |

| ADEs | 130 | 0.88 | 68 | 0.92 | 62 | 0.83 | 1.11 (0.78-1.56) | 0.96 (0.68-1.37) |

| Clinically important medication errorsc | 89 | 0.60 | 44 | 0.60 | 45 | 0.60 | 0.99 (0.65-1.49) | 0.81 (0.53-1.23) |

| Preventable/ameliorable ADEs | 66 | 0.44 | 31 | 0.42 | 35 | 0.47 | 0.89 (0.55-1.45) | 0.74 (0.45-1.22) |

| Potential ADEs | 23 | 0.15 | 13 | 0.18 | 10 | 0.13 | 1.31 (0.57-2.99) | 1.02 (0.44-2.36) |

| Serious/life-threatening preventable/ameliorable ADEs | 17 | 0.11 | 7 | 0.09 | 10 | 0.13 | 0.71 (0.27-1.85) | 0.53 (0.20-1.39) |

Abbreviations: ADE, adverse drug event; IR, incidence rate per 100 patient-days of observation; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Based on 180 patients in the intervention group contributing 7392 days of observation and 181 patients in the control group contributing 7447 days of observation. Patients could experience more than 1 event.

Models included age, sex, and having visiting nurse services.

Clinically important medication errors are a composite of preventable/ameliorable ADEs and potential ADEs.

Among all participants, 65 (18.0%) had 1 or more clinically important medication errors, comprising preventable or ameliorable ADEs and potential ADEs. There were 44 clinically important medication errors in the intervention group and 45 in the control group. The incidence rate of clinically important medication errors in the intervention group was 0.60 per 100 person-days and 0.60 per 100 person-days in the control group. The intervention did not significantly alter the per-patient rate of clinically important medication errors (unadjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.65-1.49). The adjusted incidence rate ratio was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.53-1.23).

Of the intervention patients, 33 (18.3%) had an emergency department visit sometime during the 45-day follow-up period compared with 34 (18.8%) in the control group. Twenty-nine patients (16.1%) in the intervention group did not complete the full 45 days of follow-up postdischarge because of rehospitalization (n = 28) or death (n = 1), compared with 26 (14.4%) who were rehospitalized in the control group.

For the subgroup of adverse drug-related incidents that were categorized as ADEs, gastrointestinal events were most common overall in the intervention and control groups (Table 3). Other frequently identified types of ADEs were cardiovascular, kidney/electrolyte/fluid balance (eg, kidney insufficiency, hyperkalemia, hypokalemia, and dehydration), hemorrhagic (bleeding events), and metabolic or endocrine (eg, hypoglycemia).

Table 3. Frequency of Types of Adverse Drug Events.

| Type of eventa | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 130) | Intervention (n = 68) | Control (n = 62) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 41 (31.54) | 19 (27.94) | 22 (35.48) |

| Cardiovascular | 28 (21.54) | 14 (20.59) | 14 (22.58) |

| Kidney/electrolytes/fluid balance | 20 (15.38) | 9 (13.24) | 11 (17.74) |

| Hemorrhagic | 14 (10.77) | 7 (10.29) | 7 (11.29) |

| Metabolic or endocrine | 11 (8.46) | 7 (10.29) | 4 (6.45) |

| Dermatologic | 10 (7.69) | 6 (8.82) | 4 (6.45) |

| Neuropsychiatricb | 10 (7.69) | 9 (13.24) | 1 (1.61) |

| Syncope or dizziness | 8 (6.15) | 2 (2.94) | 6 (9.68) |

| Infection | 3 (2.31) | 1 (1.47) | 2 (3.23) |

| Fall without injury | 2 (1.54) | 2 (2.94) | 0 |

| Fall with injury | 1 (0.77) | 0 | 1 (1.61) |

| Hematologic | 1 (0.77) | 0 | 1 (1.61) |

| Respiratory | 1 (0.77) | 1 (1.47) | 0 |

| Other | 5 (3.85) | 1 (1.47) | 4 (6.45) |

| Inadequate pain control | 2 (1.54) | 0 | 2 (3.23) |

| Myalgia | 1 (0.77) | 1 (1.47) | 0 |

| Night sweats | 1 (0.77) | 0 | 1 (1.61) |

| Nonspecific drug intolerance | 1 (0.77) | 0 | 1 (1.61) |

Adverse drug events could manifest as more than 1 type.

Neuropsychiatric events include oversedation, confusion, hallucinations, and delirium. Adverse drug events could manifest as more than 1 type.

Table 4 lists the medication categories that were most frequently associated with all adverse drug- related incidents and those associated with clinically important medication errors in the intervention and control groups of patients. Opioids constituted the most commonly implicated medication category in the intervention and control groups. Other common medication categories were cardiovascular medications, anticoagulants, and diuretics.

Table 4. Frequency of All Adverse Drug-Related Incidentsa and CIMEsb According to Drug Categoryc.

| Drug category | No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Intervention | Control | ||||

| All incidents (N = 153) | CIMEs (N = 89) | All incidents (n = 81) | CIMEs (n = 44) | All incidents (n = 72) | CIMEs (n = 45) | |

| Opioid | 42 (27.45) | 27 (30.34) | 22 (27.16) | 13 (29.55) | 20 (27.78) | 14 (31.11) |

| Cardiovascular | 31 (20.26) | 19 (21.35) | 18 (22.22) | 13 (29.55) | 13 (18.06) | 6 (13.33) |

| Anticoagulant | 22 (14.38) | 13 (14.61) | 11 (13.58) | 6 (13.64) | 11 (15.28) | 7 (15.56) |

| Diuretic | 21 (13.73) | 14 (15.73) | 9 (11.11) | 5 (11.36) | 12 (16.67) | 9 (20.00) |

| Steroid | 14 (9.15) | 8 (8.99) | 6 (7.41) | 1 (2.27) | 8 (11.11) | 7 (15.56) |

| Antiepileptic | 9 (5.88) | 8 (8.99) | 7 (8.64) | 6 (13.64) | 2 (2.78) | 2 (4.44) |

| Anti-infective | 9 (5.88) | 2 (2.25) | 5 (6.17) | 1 (2.27) | 4 (5.56) | 1 (2.22) |

| Antiplatelet | 9 (5.88) | 3 (3.37) | 4 (4.94) | 1 (2.27) | 5 (6.94) | 2 (4.44) |

| Diabetes/hypoglycemic | 9 (5.88) | 8 (8.99) | 5 (6.17) | 4 (9.09) | 4 (5.56) | 4 (8.89) |

| Nutrient or supplement | 9 (5.88) | 5 (5.62) | 6 (7.41) | 2 (4.55) | 3 (4.17) | 3 (6.67) |

| Gastrointestinal | 7 (4.58) | 5 (5.62) | 6 (7.41) | 4 (9.09) | 1 (1.39) | 1 (2.22) |

| Sedative or hypnotic | 5 (3.27) | 4 (4.49) | 5 (6.17) | 4 (9.09) | 0 | 0 |

| Antidepressant | 3 (1.96) | 3 (3.37) | 3 (3.70) | 3 (6.82) | 0 | 0 |

| DMARDs | 3 (1.96) | 1 (1.12) | 0 | 0 | 3 (4.17) | 1 (2.22) |

| NSAIDs | 3 (1.96) | 3 (3.37) | 2 (2.47) | 2 (4.55) | 1 (1.39) | 1 (2.22) |

| Respiratory | 3 (1.96) | 3 (3.37) | 2 (2.47) | 2 (4.55) | 1 (1.39) | 1 (2.22) |

| Antineoplastic | 2 (1.31) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.78) | 0 |

| Aspirin | 2 (1.31) | 1 (1.12) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.78) | 1 (2.22) |

| Dermatologic | 2 (1.31) | 1 (1.12) | 1 (1.23) | 0 | 1 (1.39) | 1 (2.22) |

| Antihyperlipidemic | 1 (0.65) | 1 (1.12) | 1 (1.23) | 1 (2.27) | 0 | 0 |

| Immunomodulator | 1 (0.65) | 0 | 1 (1.23) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Muscle relaxant | 1 (0.65) | 0 | 1 (1.23) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ophthalmic | 1 (0.65) | 1 (1.12) | 1 (1.23) | 1 (2.27) | 0 | 0 |

| Topical | 1 (0.65) | 1 (1.12) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.39) | 1 (2.22) |

| Vaccine | 1 (0.65) | 1 (1.12) | 1 (1.23) | 1 (2.27) | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviations: CIMEs, clinically important medication errors; DMARDs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

All drug-related adverse incidents were defined as all adverse drug events combined with potential adverse drug events.

The CIMEs were defined as preventable or ameliorable adverse drug events combined with potential adverse drug events.

Drugs in more than 1 category were associated with some events. Frequencies in each column sum to greater than the total number of events.

Discussion

Clinical pharmacist-directed transitional care interventions are widely considered among the most promising approaches for improving medication safety following hospital discharge. Patients who are prescribed high-risk medications, including anticoagulants, diabetes agents, and opioids, at the time of hospital discharge should be an ideal population to target for such interventions. In this randomized clinical trial of a multifaceted, pharmacist-directed intervention, we did not observe a significantly lower rate of adverse drug-related incidents or clinically important medication errors among such patients during the immediate posthospitalization period. However, we did experience challenges in achieving recruitment goals, despite extending the period of recruitment by 1 year,11 and found substantially lower than expected rates of events compared with a prior study,12 which limited our power to detect differences between intervention and control patients.

To our knowledge, few high-quality studies have rigorously examined the effect of pharmacist-based interventions on medication safety in the ambulatory setting. Lee and colleagues25 conducted a systematic review of pharmacist interventions that was focused on older adults. Of the 20 studies ultimately included in the systematic review, only 6 were randomized clinical trials, and only 1 focused on ADEs and medication safety. In that study, while inappropriate prescribing was reduced, there was no statistically significant difference in the percentage of patients who experienced an ADE in the intervention compared with the control group.26

A more recent review highlighted the fact that very few studies have examined the effects of pharmacist-directed medication safety interventions on medication safety following hospital discharge.27,28,29 While some studies have suggested medication safety benefits from inpatient pharmacist-based interventions at the time of hospital discharge,30,31 others have not. In a randomized trial of adults hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes or acute decompensated heart failure, a multicomponent intervention comprising pharmacist-assisted medication reconciliation at the time of discharge failed to demonstrate a significant reduction in clinically important medication errors.12 These investigators emphasized that their findings “highlighted the difficulty of improving medication safety during the transition from hospital to home.”12 The failure of that intervention has been attributed to several factors, including inadequate communication and collaboration with the primary care team of the patient during this vulnerable transition period,32 an issue that we addressed in our study. To our knowledge, only 1 study of a pharmacist-led transitional care intervention that focused on medication safety has demonstrated a significantly reduced risk for a broadly defined outcome of “medication-related problems.”33 However, that study was limited by a pre-post study design and nonadjudicated outcomes.

Strengths and Limitations

While our study had several strengths, including a randomized trial design, multicomponent intervention, and rigorous process to adjudicate outcomes, there were several limitations. The intervention was initiated following hospital discharge rather than in the hospital setting, which precluded our ability to intervene on patients at the earliest possible point during the transition process from hospital to home. Visits by clinical pharmacists to the homes of patients did not immediately follow hospital discharge, which delayed efforts to address medication safety issues at the earliest possible point during the transition period. Study participants could also receive visiting nursing services, which were provided to more than half of the patients in the study. However, more intervention patients received these services than control patients, which would have biased our study findings toward an effect. There was the possibility that by identifying and alerting the primary care clinician to potential medication safety problems, the intervention may have led to greater documentation and assessment of these problems and resultant events being detected in the intervention than in the control group. It is also possible that the intervention itself had a training effect on patients in fostering detection and the reporting of medication safety issues to health care clinicians by patients in the intervention group. In addition, participants in the control group were provided the high-risk medication educational materials via mail, which could be considered enhanced usual care, and which may have attenuated the effect of the intervention. Finally, our study was limited to the immediate 45-day post–hospital discharge period, while ongoing efforts by community pharmacists working with patients up to a year postdischarge may be beneficial in reducing medication harm.34,35

Conclusions

These study findings should not dampen enthusiasm for developing, testing, and refining interventions to enhance medication safety during the high-risk, post–hospital discharge transition period. Such efforts are costly, challenging, and complex, and health care systems and payers require a clear understanding of the effectiveness of these interventions to make the investments and address the challenges inherent in implementing them. Rigorous evaluations are essential so that these important and necessary efforts can be improved on and promoted with confidence for widespread adoption.

Trial protocol

Categories of outcome events

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345-349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):549-555. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100-102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1212324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . National action plan for adverse drug event prevention. Accessed January 12, 2015. http://www.health.gov/hai/pdfs/ADE-Action-Plan-508c.pdf

- 6.Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):2002-2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Budnitz DS, Pollock DA, Weidenbach KN, Mendelsohn AB, Schroeder TJ, Annest JL. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA. 2006;296(15):1858-1866. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Budnitz DS, Shehab N, Kegler SR, Richards CL. Medication use leading to emergency department visits for adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(11):755-765. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Field TS, Mazor KM, Briesacher B, Debellis KR, Gurwitz JH. Adverse drug events resulting from patient errors in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):271-276. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01047.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarkar U, Schillinger D, López A, Sudore R. Validation of self-reported health literacy questions among diverse English and Spanish-speaking populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(3):265-271. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1552-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anzuoni K, Field TS, Mazor KM, et al. Recruitment challenges for low-risk health system intervention trials in older adults: a case study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(11):2558-2564. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kripalani S, Roumie CL, Dalal AK, et al. ; PILL-CVD (Pharmacist Intervention for Low Literacy in Cardiovascular Disease) Study Group . Effect of a pharmacist intervention on clinically important medication errors after hospital discharge: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(1):1-10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201207030-00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aspden P. (U.S.) Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medication Errors. Preventing Medication Errors. National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bates DW, Leape LL, Cullen DJ, et al. Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. JAMA. 1998;280(15):1311-1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Avorn J, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events in nursing homes. Am J Med. 2000;109(2):87-94. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00451-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA. 2003;289(9):1107-1116. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Judge J, et al. The incidence of adverse drug events in two large academic long-term care facilities. Am J Med. 2005;118(3):251-258. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Radford MJ, et al. The safety of warfarin therapy in the nursing home setting. Am J Med. 2007;120(6):539-544. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2114-2120. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Clapp MD, et al. Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 1999;282(3):267-270. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.3.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh KE, Mazor KM, Stille CJ, et al. Medication errors in the homes of children with chronic conditions. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(6):581-586. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.204479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, et al. ; ADE Prevention Study Group . Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. JAMA. 1995;274(1):29-34. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530010043033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ, et al. ; Adverse Drug Events Prevention Study Group . The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1997;277(4):307-311. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540280045032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leape LL, Bates DW, Cullen DJ, et al. ; ADE Prevention Study Group . Systems analysis of adverse drug events. JAMA. 1995;274(1):35-43. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530010049034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JK, Slack MK, Martin J, Ehrman C, Chisholm-Burns M. Geriatric patient care by U.S. pharmacists in healthcare teams: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(7):1119-1127. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, Samsa GP, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a clinical pharmacist intervention to improve inappropriate prescribing in elderly outpatients with polypharmacy. Am J Med. 1996;100(4):428-437. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)89519-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daliri S, Boujarfi S, El Mokaddam A, et al. Medication-related interventions delivered both in hospital and following discharge: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;bmjqs-2020-010927. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-010927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farris KB, Carter BL, Xu Y, et al. Effect of a care transition intervention by pharmacists: an RCT. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:406. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phatak A, Prusi R, Ward B, et al. Impact of pharmacist involvement in the transitional care of high-risk patients through medication reconciliation, medication education, and postdischarge call-backs (IPITCH Study). J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):39-44. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1057-1069. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):565-571. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Criddle DT. Effect of a pharmacist intervention. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(2):137. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-2-201301150-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daliri S, Hugtenburg JG, Ter Riet G, et al. The effect of a pharmacy-led transitional care program on medication-related problems post-discharge: a before-After prospective study. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pellegrin K, Lozano A, Miyamura J, et al. Community-acquired and hospital-acquired medication harm among older inpatients and impact of a state-wide medication management intervention. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(2):103-110. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pellegrin KL, Krenk L, Oakes SJ, et al. Reductions in medication-related hospitalizations in older adults with medication management by hospital and community pharmacists: a quasi-experimental study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(1):212-219. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

Categories of outcome events

Data sharing statement