Highlights

There is no dearth of literature on pulmonary involvement in COVID-19 infection. However, extra-pulmonary manifestations are rare and can be easily missed during this pandemic. Our case series hopes to highlight the fact that neurological manifestations of COVID-19 infection are likely to be overlooked. Hence, a low threshold of clinical suspicion and testing for COVID-19 infection is needed in cases presenting with primary neurological symptoms. This will facilitate quicker detection, isolation of cases to prevent further transmission, and provision of early treatment.

Keywords: Cerebrovascular accident, COVID-19, Encephalitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, Neurological, SARS-CoV-2

Abstract

Identification of neurological manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2) in patients with no or mild pulmonary infection proves to be a challenge. The incidence of neurological associations of COVID-19 may be small as compared with respiratory disease; however, in the present scenario with an increasing number of cases each day, the overall incidence of patients with neurological manifestations and their health-related socioeconomic impact might be large. Hence it is important to report such cases so that healthcare providers and concerned authorities are aware of and may prepare for the growing burden. The literature on primary neurological manifestations of COVID-19 is limited, and hence our case series is relevant in the current scenario. The most commonly reported neurological complications are cerebrovascular accidents, encephalopathy, encephalitis, meningitis, and Guillain-Barr é syndrome (GBS). We present a series of seven cases with various neurological presentations and possible complications from this novel virus infection.

How to cite this article

Goel K, Kumar A, Diwan S, Kohli S, Sachdeva HC, Usha G, et al. Neurological Manifestations of COVID-19: A Series of Seven Cases. Indian J Crit Care Med 2021;25(2):219–223.

Introduction

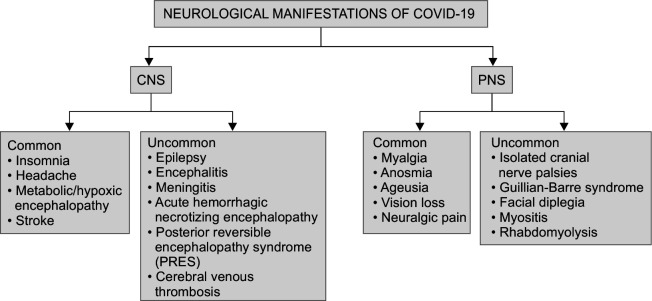

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak due to SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2) first originated from Wuhan city, China in December 2019 and has rapidly spread as a global health pandemic.1,2 This infection has been demonstrated to produce a mild flu-like illness encompassing fever, cough, breathlessness, and other mild symptoms, such as headache, lethargy, and generalized weakness in a majority of patients.3 Originally considered a primarily respiratory disease,4 new facts have emerged regarding extra-pulmonary complications of the COVID-19 illness. Neurological manifestations are common in the advanced stages of the disease.5 Although the exact mechanism by which SARS-CoV-2 penetrates the central and peripheral nervous system (CNS and PNS) is not yet known, the two most likely theories are (1) hematogenous spread of SARS-CoV-2 from systemic circulation to the cerebral circulation and (2) dissemination through the cribriform plate and olfactory bulb.6 Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE 2) receptors that are present on endothelial cells of the cerebral vasculature act as the cell entry points of the virus.7 It may also induce certain microvascular/macrovascular changes leading to nervous system involvement.8 We have compiled a case series of confirmed COVID-19 patients who presented with or developed primary neurological manifestations, to better understand the neurological aspect of this disease. The neurological manifestations of COVID-19 are described in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Neurological manifestations of COVID-19 infection

Case Description

A total of seven RT-PCR (real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction) confirmed COVID-19 patients presented to our institute primarily with neurological manifestations (Tables 1 and 2). Two of these cases presented with altered sensorium and a recent history of fever, whereas another two presented with paraparesis. One case presented with hemiplegia and two cases presented with loss of consciousness. Out of the two unconscious patients, one had a history of generalized weakness and the other had dyspnoea one day prior to admission. Apart from dyspnea in this patient, no respiratory symptoms were noted in any of the other cases. None of these patients had a history of travel to a foreign country or contact with a confirmed case of COVID-19. Out of all the seven patients, only two had chest X-ray changes, i.e., homogenous opacities and partial one-sided lung collapse in one and fluffy infiltrates in the other. Five of the patients tested positive in the initial tests while two (case numbers 6 and 7) were initially negative and tested positive after admission in non-COVID ICU. Neurology consultation was sought for patient management at every stage.

Table 1.

Clinical findings of cases

| No. | Age/sex | Clinical presentation | Classical COVID-19 symptoms | Comorbidities | Final diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 55 years/M | Left hemiparesis × 1 day | None | Hypertension T2DM | COVID-19 with CVA | Antibiotics Phenytoin, mannitol Antithrombosis Steroids |

Expired |

| 2 | 56 years/M | Unconsciousness × 1 day Generalized weakness × 1 week | None | T2DM | COVID-19 with CVA | Antibiotics Phenytoin, mannitol Antithrombosis Steroids |

Expired |

| 3 | 59 years/F | Unconsciousness × 1 day | Dyspnea × 1 day | T2DM Hypertension | COVID-19 with influenza-like illness with CVA | Antibiotics Phenytoin, mannitol Antithrombosis Steroids |

Expired |

| 4 | 37 years/F | Altered sensorium × 1 day Fever × 6 days Seizure × 1 episode |

Fever × 6 days | None | COVID-19 associated CNS infection | Antibiotics Thromboprophylaxis Steroids Levetiracetam |

Expired |

| 5 | 19 years/F | Altered sensorium × 10 days Vomiting × 5 days |

Fever × 10 days | None | COVID-19 associated CNS infection | Antibiotics Levetiracetam Thromboprophylaxis Steroids |

Critically ill |

| 6 | 55 years/F | Paraparesis × 6 days Low backache × 6 days |

None | Hypertension | COVID-19 with GBS, complicated by PRES | IVIG Antibiotics Thromboprophylaxis Steroids |

Expired |

| 7 | 17 years/M | Progressive ascending quadriparesis × 2 days | Fever at presentation | None | COVID-19 with GBS with septic shock | Antibiotics IVIG Thromboprophylaxis Steroids |

Expired |

CVA, cerebrovascular accident; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulins

Table 2.

Laboratory and radiological findings of cases

| Case no. | Age/sex | Neuroradiology | CSF study/neurophysiology | Chest X-ray | RT-PCR | Relevant blood investigations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 55 years/M | NCCT: Right MCA territory subacute infarct with no hemorrhagic transformation | Not performed | Bilateral homogeneous opacities with partial right lung collapse | Positive Day 2 | Leukocytosis Neutrophilia Lymphopenia Hyponatremia |

| 2 | 56 years/M | MRI: Left MCA (massive) and Right ACA infarct | Not performed | Unremarkable | Positive Day 2 | Lymphopenia Neutrophilia Raised CRP Deranged liver function D-dimer: 3250 ng/mL |

| 3 | 59 years/F | NCCT: Multiple subacute cortical infarcts | Not performed | Bilateral infiltrates | Positive Day 2 | Anemia Thrombocytopenia D-dimer: 4018 ng/mL Serum ferritin: 226 ng/mL |

| 4 | 37 years/F | NCCT: Normal | CSF: Normal protein and cell count | Unremarkable | Positive Day 6 Negative Day 11 | Leukocytosis Neutrophilia Lymphopenia D-dimer: 2994 ng/mL |

| 5 | 19 years/F | NCCT: Diffuse cerebral edema | CSF: Raised proteins and cell count | Unremarkable | Positive Day 10 | Leukocytosis Lymphopenia Neutrophilia Hyponatremia D-dimer: 2348 ng/mL |

| 6 | 55 years/F | MRI: features of PRES | CSF: Raised proteins, normal cell count NCV: Axonal and demyelinating sensorimotor polyneuropathy | Unremarkable | Positive Day 10 Negative Day 19 and 21 | Anemia Lymphopenia Thrombocytopenia Hyponatremia D-dimer: 1804 ng/mL Serum procalcitonin: 2.02 |

| 7 | 17 years/M | MRI brain: Normal MRI spine: Normal | CSF: Raised proteins, normal cell count NCV: demyelinating sensorimotor polyneuropathy | Unremarkable | Negative Day 1 Negative Day 3 Positive Day 8 | Mild leukocytosis Lymphopenia Neutrophilia Hyponatremia D-dimer: 890 ng/mL |

NCCT, non-contrast computed tomography; MCA, middle cerebral artery; ACA, anterior cerebral artery; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CRP, C-reactive protein; NCV, nerve conduction velocity; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid

Discussion

This case series was observed in a single center, catering to COVID as well as non-COVID patients, from June to August 2020. At the onset of the pandemic, the main focus was on patients presenting with respiratory symptoms. So a higher threshold of suspicion of COVID-19 disease was maintained for patients presenting with clear-cut neurological manifestations, without any pulmonary involvement. However, with an increasing number of cases, the focus was shifted towards the possibility of neurological association of COVID-19, and an attempt was made to gather more data in this direction.

It may be remarkable to note that all patients in this case series were less than 60 years of age (mean age 40.1 years), with two of these patients less than 20 years. The patients had a relatively even sex distribution in this case series with three male and four female patients. Four out of seven patients had comorbidities usually associated with a worse outcome, i.e., hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Table 3 shows the consolidated data from various studies that have contributed to a better understanding of our cases.

Table 3.

Review of literature on neurological manifestations in COVID infection

| Reference | Country | Clinical features | COVID RT-PCR | Neuroimaging, CSF findings | Blood investigations | Treatment and outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxley et al. 9 5 cases (CVA) | USA | Hemiplegia, altered consciousness, sensory deficits, dysarthria | All positive | Single territory infarcts on imaging No CSF studies |

One patient had thrombocytopenia, two had deranged clotting parameters, three had raised fibrinogen, D-dimer, and ferritin | Four had clot retrieval, one thrombolysis, and hemicraniectomy, one stent insertion Three discharged, two in hospital |

| Beyrouti et al. 10 6 cases (CVA) | UK | Hemiparesis, dysphasia, dysarthria, altered consciousness Presented with a median of 13 days after respiratory symptoms |

All positive | Unifocal infarcts in 4 patients, Bilateral infarcts in 2 patients | One had leukocytosis and three had lymphopenia, all had raised D-dimers and lactate dehydrogenase, 5 had raised ferritin and CRP | One had dual antiplatelets and LMWH (low-molecular-weight heparin), one had extra-ventricular drain placement and LMWH, one had apixaban One died and the rest outcome unknown |

| Mao et al. 11 16 cases (CNS infection) | China | Unconsciousness Seizures |

All positive | Not reported | Lymphocytopenia Thrombocytopenia Raised blood urea nitrogen (BUN) |

13 out of 16 had severe dyspnea |

| Toscano et al.12 5 cases (GBS) | Italy | 3 had quadriparesis, 1 had paraparesis 1 had facial diplegia and limb paresthesia Presented after a median of 7 days of respiratory symptoms |

4 positive by nasopharyngeal swabs, 1 positive serologically, all negative in CSF RT-PCR | MRI: enhancement of caudal nerve roots in two patients and facial nerve in one NCV: axonal pattern in three patients and demyelinating in two |

Not reported | All treated with IVIG, one also had plasma exchange Three required mechanical ventilation |

USA and UK have also reported multiple cases of COVID patients presenting with CVA, mostly older patients with the majority being ischemic strokes. Oxley et al.9 reported five such cases which notably consisted of patients younger than 50 years. In our series, all three cases were under 60 years with known risk factors for CVA and diagnosed as ischemic stroke. The first patient in our case series expired within a day of admission and was later found to be COVID positive. This gave us a reason to search for literature on the neurological presentation of COVID infection. Going forward, we have found more cases and evidence of hypercoagulability in COVID patients presenting with stroke. The first patient did not survive long enough to allow D-dimer testing, but the second and third patients showed high values. Beyrouti et al.10 reported six patients with large cerebral infarcts with elevated D-dimer levels indicating a hypercoagulable state. The third case in our series is different from the first two, as he had associated shortness of breath on presentation, which led to a quicker diagnosis of COVID-19. This patient had NCCT head changes suggestive of embolism or vasculitis associated infarcts which may be considered a complication rather than a manifestation of COVID-19.

The next two cases in our series had altered sensorium at presentation and encephalitis/meningitis was suspected based on a history of fever with neurological signs. When tested, they were found to be COVID-19 positive. Moriguchi et al.13 reported the first confirmed case of COVID-19 associated viral encephalitis from Japan. A 24-year-old man presented with fever followed by seizures and unconsciousness. He had neck stiffness and underwent a CT scan brain which was normal. There was patchy pneumonia on the CT chest. PCR assay from nasopharyngeal swab was negative but the CSF sample was positive for COVID-19. This presentation may justify the inclusion of the fourth and fifth cases, which had similar initial CNS findings but without any pulmonary involvement. Although it is difficult to diagnose COVID-19 associated CNS infection in such cases, it becomes prudent to keep a high index of suspicion, especially in the middle of a pandemic and absence of any other definitive cause.

There have been several cases reported from China and Italy of GBS associated with COVID-19. The first such case was reported from China of a 61-year-old lady with a history of return from Wuhan but no respiratory symptoms.14 She was however infective as two of her relatives caring for her during her hospital stay were found positive for SARS-CoV-2. She later developed fever and cough during her hospital stay. In contrast, the 55-year-old lady, the sixth case in our series, had no history of travel or contact with a confirmed case, or the classical presentation of a febrile illness. She presented to us with paraparesis only and her hospital stay was complicated by PRES. Whether this neurological involvement was causal or coincidental is difficult to say as the patient presented late to the hospital, having gone to a secondary health center previously and there was a further delay in COVID testing due to the complete absence of usual respiratory symptoms. The last case of a 17-year-old boy presented with a relatively faster progression of the disease and developed high-grade fever during his illness, possibly due to sepsis with no response to high-grade antibiotics.

Conclusion

As initially perceived, the SARS-COV-2 virus is not only responsible for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases but also neurological morbidity. This may be secondary to micro/macrovascular changes in the CNS or the PNS or due to a direct invasion of the cerebral endothelium/parenchyma by the virus hematogenously. To make a clear distinction, further studies need to be undertaken with the help of multidisciplinary teams of critical care, neurology, internal medicine, pathology, microbiology, and radiology departments. A low threshold of COVID-19 testing needs to be kept in cases with neurological presentations, particularly in areas with higher COVID-19 infection rates to improve quicker detection, provide early treatment, and isolate such cases to prevent further transmission in highly susceptible critical patients.

Justification of Study

Our case series hopes to highlight the fact that extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19 infection are likely to be missed. Hence, a low threshold of testing must be kept in such cases to improve quicker detection, isolation of cases to prevent further transmission, and provision of early treatment.

Orcid

Kavya Goel https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5427-5347

Ajay Kumar https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5643-7955

Sahil Diwan https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6489-802X

Santvana Kohli https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1410-6933

Harish C Sachdeva https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4476-0506

Usha Ganapathy https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5472-5769

Saurav M Mustafi https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0893-2155

Pravin Kumar https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4827-6650

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

References

- 1.Zu ZY, Jiang MD, Xu PP, Chen W, Ni QQ, Lu GM, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a perspective from China. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E15–E25. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200490. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green A. Li Wenliang. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):682. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30456-6. DOI: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, Clere-Jehl R, Schenk M, Kummerlen C, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2268–2270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2008597. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baig AM, Khaleeq A, Ali U, Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: tissue distribution, host–virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11(7):995–998. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00122. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li MY, Li L, Zhang Y, Wang XS. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor gene ACE2 in a wide variety of human tissues. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00662-x. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasal DA, De Lorenzo A, Tibiriçá E. COVID-19 and microvascular disease: pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2 Infection with focus on the renin-angiotensin system. Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29(11):1596–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2020.08.010. DOI: (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, Kellner CP, Shoirah H, Singh IP, et al. Largevessel stroke as a presenting feature of COVID-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):e60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beyrouti R, Adams ME, Benjamin L, Cohen H, Farmer SF, Goh YY, et al. Characteristics of ischaemic stroke associated with COVID-19. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(8):889–891. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323586. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):683–690. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toscano G, Palmerini F, Ravaglia S, Ruiz L, Invernizzi P, Cuzzoni MG, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2574–2576. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009191. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, Harada D, Sugawara H, Takamino J, et al. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao H, Shen D, Zhou H, Liu J, Chen S. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: causality or coincidence? Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(5):383–384. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30109-5. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]