Abstract

Despite an excellent track record, microbial drug discovery suffers from high rates of rediscovery. Better workflows for the rapid investigation of complex extracts are needed to increase throughput and to allow early prioritization of samples. In addition, systematic characterization of poorly explored strains is seldomly performed. Here, we report a metabolomic study of 72 isolates belonging to the rare actinomycete genus Planomonospora, using a workflow of commonly used open access tools to investigate its secondary metabolites. The results reveal a correlation of chemical diversity and strain phylogeny, with classes of metabolites exclusive to certain phylogroups. We were able to identify previously reported Planomonospora metabolites, including the ureylene-containing oligopeptide antipain, the thiopeptide siomycin including new congeners, and the ribosomally synthesized peptides sphaericin and lantibiotic 97518. In addition, we found that Planomonospora strains can produce the siderophore desferrioxamine or a salinichelin-like peptide. Analysis of the genomes of three newly sequenced strains led to the detection of 59 gene cluster families, of which three were connected to products found by LC-MS/MS profiling. This study demonstrates the value of metabolomic studies to investigate poorly explored taxa and provides a first picture of the biosynthetic capabilities of the genus Planomonospora.

Natural products are excellent sources for bioactive scaffolds. Over the last four decades, 66% of approved small-molecule drugs were actual natural products or at least inspired from such.1 This is an impressive track record, considering the general withdrawal of industrial activity from the field.2 One reason for this disinterest has been the frequent rediscovery of known molecules in activity-based screenings, especially in microbe-derived extracts.3 However, the focus on bioactivity as selection criterion provides a biased perspective on a small portion of the chemical diversity microbes are capable to produce. Despite decades of research, the majority of secondary metabolites remain “metabolomic dark matter”,4 with high probability of structural novelty5 and novel bioactive scaffolds.6 Streamlined approaches for strain prioritization and workflow optimization are needed to render drug discovery from microbial sources a cost-effective endeavor.5

Recent advances in genome mining have enabled researchers to investigate the biosynthetic potential of bacteria in silico, with minimal wet lab work.7 Tools such as antiSMASH8 mine genomes for biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), while BGC repositories such as MIBiG9 aid in the evaluation of BGC novelty. In addition, advances in (tandem) mass spectrometry and the introduction of molecular networking,10 the tandem mass (MS2)-based grouping of molecules by structural relatedness, has made untargeted metabolomics broadly available,11 while public databases such as GNPS12 and the Natural Product Atlas13 facilitate metabolite annotation. These methods allow researchers to rationalize resources and quickly prioritize strains or metabolites for further investigations. Earlier studies on bacterial genera, such as the actinobacteria Salinispora(14−16) and Nocardia,17 the myxobacterium Myxococcus,18 and the γ-proteobacterium Pseudoalteromonas(19) have demonstrated distinct chemical profiles and shown correlations between taxonomic and metabolomic diversity.

Our group is particularly interested in exploring the metabolic capabilities of rare genera of actinomycetes present within the Naicons collection, which comprises approximately 45 000 actinomycete strains of diverse origin, isolated between 1960 and 2005.20 One such genus is Planomonospora. Originally described by researchers from Lepetit (the predecessor company of Naicons) in 1967,21 six species, two subspecies, and four unclassified strains can be found in public collections or databases. Few molecules have been described as produced by this genus: the thiopeptides thiostrepton22 and siomycin, also known as sporangiomycin;23,24 lantibiotic 97518, also known as planosporicin,25,26 a member of a family of class I lantipeptides produced by many actinobacterial genera;27 the lassopeptide sphaericin;28 and the ureylene-containing oligopeptide antipain,29 which is also produced by Streptomyces.30 Here, the capability of Planomonospora strains to produce secondary metabolites is accessed, using a pipeline of freely available tools for metabolome and genome mining for the prioritization of promising strains and/or metabolites for further investigation (see Figure 1). Similar workflows have been reported by other groups.11,31−36 The investigation was carried out on 72 strains from the Naicons collection and was complemented with genomic analyses of selected strains. This study gives unprecedented insight into the rare genus Planomonospora, correlating metabolites to their putative BGCs and making way for targeted isolation efforts.

Figure 1.

Visualization of workflow: Strains are cultivated and extracts are prepared and analyzed. (A) Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode on an LC-ESI-HR-MS/MS-instrument. Data are preprocessed with the MZmine 2 software, yielding a list of features, which are then analyzed by GNPS feature-based molecular networking, with consecutive MS2LDA curation. (B) Taxonomy of the strains is established by 16S rRNA-sequencing. Strains/features are prioritized for consecutive targeted isolation.

Results and Discussion

Determination of Phylogenetic Affiliation

From the approximately 350 Planomonospora entries listed in the Naicons collection, 72 strains confirmed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing as belonging to the genus Planomonospora were selected. The majority were isolated from soil originating from central Africa and the Mediterranean region. The 72 strains yielded 35 unique 16S rRNA sequences, 31 of which had not been previously reported (see Figures S1 and S2). The resulting phylogenetic tree (see Figure 2) was found to be in agreement with previous studies37,38 and showed three phylogroups with a relevant number of representatives: Phylogroup C includes 13 strains (9 of them from Naicons collection) and 9 distinct 16S rRNA sequences; phylogroup A2 includes 12 strains (11 of them from Naicons collection) and 8 distinct 16S rRNA sequences. The most populated phylogroup S includes 46 strains (43 of them from Naicons collection) and 13 distinct 16S rRNA sequences. In addition, the phylogenetic analysis yielded three poorly represented phylogroups: V1, which includes Planomonospora venezuelensis JCM3167 and Naicons strain ID43178, with identical 16S rRNA sequences; the somehow related V2 group, with six distinct Naicons isolates with identical sequences; and A1, with just two Naicons strains with identical sequences. All phylogroups contained sequences of previously described Planomonospora species, except V2 and A1. Given the extent of sequence distance from validly described species (see Figures S1 and S2), many of the Naicons strains likely represent new species within this genus. In the following analyses, we consider V1 as a phylogroup, even though it contains only one strain.

Figure 2.

16S rRNA-based phylogenetic tree of Planomonospora (P.) strains. Naicons strains are represented by their ID numbers in boldface. Type strains and two unclassified strains with complete 16S sequences are indicated in italics. Naicons strains with identical sequences are represented by a single ID number, with the number of additional strains in parentheses (details in Figures S1 and S2). Bootstrap values (1000 times resampled) higher than 60% are indicated in bold type. Planobispora rosea ATCC53733 was used as outgroup.

Cultivation, Extraction, and Molecular Network Analysis

To find appropriate cultivation conditions for the Planomonospora strains, the behavior of a selected number of isolates under a variety of different conditions, including three solid and six liquid media, was investigated. Four liquid media (AF, R3, MC1, and AF2, see Experimental Procedures) afforded the highest metabolic diversity (data not shown) and were used in the following analyses.

Cultivation of the 72 strains in the four media and preparation of two extracts per culture yielded 576 samples. To expedite analysis, the two extracts from each culture were combined, yielding 288 samples, two of which were removed due to cross-contamination. The remaining 286 samples were analyzed by LC-ESI-HR-MS/MS in data-dependent acquisition mode. The LC-MS/MS data were subjected to a workflow consisting of several steps (see Figure 1): Files were (i) preprocessed with the feature finding tool MZmine 2 to correct for m/z and retention time drift, to differentiate between structural isomers that had been separated by chromatography, and to reduce redundancy of data by merging duplicates;31,39 (ii) analyzed using the feature-based molecular networking workflow of GNPS;12,40 and (iii) visualized using the program Cytoscape41 (see Figure S3). This resulted in a feature-based molecular network, a visual, topological representation of the chemistry detected by mass spectrometry. In such a network, the features (each with corresponding m/z, retention time, and MS2-spectrum) detected during the preceding feature finding step are organized into subnetworks, also called molecular families or clusters, based on the similarity of their associated MS/MS spectra (see Figure S3 for more details). This is based on the observation that similar molecules generally show similar MS2 fragmentation.10 Features can also remain singletons, if they have sufficiently unique MS2 spectra not to cluster with any other feature. Sample metadata, such as producing strain, cultivation medium, and phylogroup affiliation, can be mapped onto the molecular network, which supports intuitive assessment and helps in data organization.

In the resulting molecular network, media components, background impurities from the extraction process, and features with an m/z less or equal to 300 were removed beforehand. The last step excluded approximately 650 features which are likely to include metabolites that would be hard to dereplicate due to limited MS2 information and lack of an appropriate database for the genus. Indeed, a preliminary analysis utilizing the GNPS libraries resulted in zero dereplications, with 90% of features being singletons (data not shown). Despite the opportunity to discover novel metabolites in this mass range, we chose to focus on higher molecular weight molecules.

Of the remaining 1492 features in the molecular network in Figure 3, 447 (30%) were organized in 60 different clusters, while 1045 features remained singletons. The number of features is not equivalent to the number of metabolites, because the same metabolite can be detected as different adducts (and thus features) by ESI mass spectrometry (e.g., [M + H]+, [M + 2H]2+, [M + 2H + Fe]+, [M + Na]+, ...).

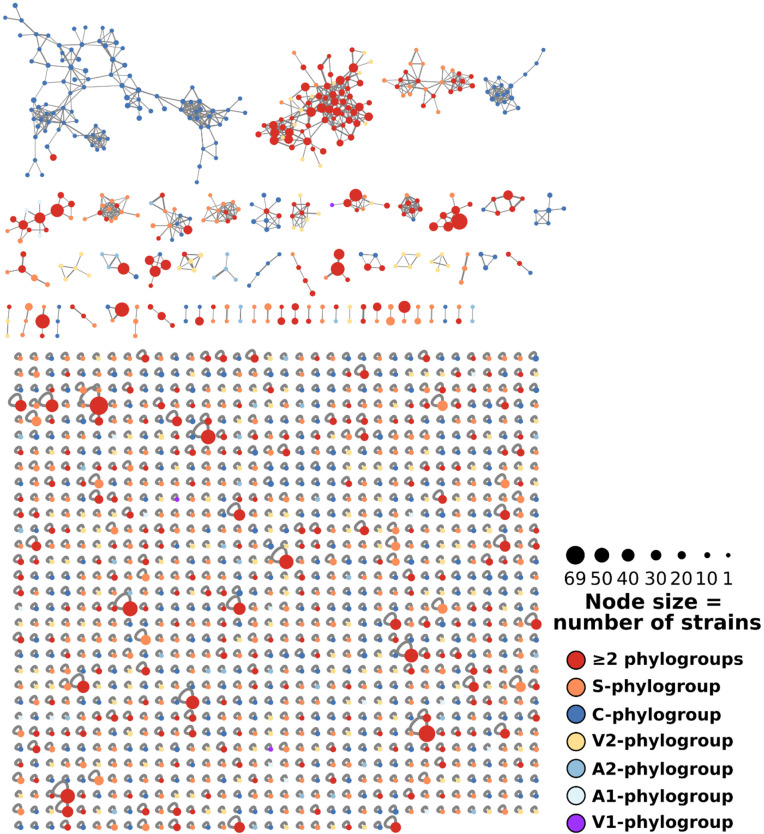

Figure 3.

Complete molecular network of 286 Planomonospora extracts, encompassing 1492 features (nodes). Features (447) were organized in 60 clusters. Node size correlates to the number of contributing strains, while the colors give the contributing phylogroup(s).

A recent study on myxobacteria demonstrated a strong correlation between taxonomic and secondary metabolite diversity; i.e., metabolite profiles showed high taxonomic specificity.42 This raised the question whether this applied to Planomonospora. Only 1% of features were detected in members of all phylogroups, as shown by the Venn diagram in Figure 4A. The vast majority (74%) of the 1492 features were phylogroup-specific, meaning that they were not detected in samples derived from strains of a different phylogroup. The number of specific features was especially high for phylogroup C; 31% of all detected features were exclusive to its 9 members. This is consistent with the phylogenetic tree of Figure 2, which indicates that phylogroup C is more divergent from the other well-represented phylogroups A and S. In contrast, the number of phylogroup-specific features was relatively low in groups A1 and A2, suggesting that the separation into two phylogroups might be an artifact due to the existence of only one 16S rRNA sequence in phylogroup A1. Overall, the results suggest that secondary metabolite production in Planomonospora ssp. is a phylogroup-defining trait.

Figure 4.

Distribution of 1492 features according to (A) phylogroups and (B) strains. In panel A, overlaps amounting to less than 1% are not labeled, while features detected in phylogroup V1 were omitted from the analysis. In panel B, each bar represents a different strain. Bars are separated into strain-specific (red), phylogroup-specific (yellow, detected in at least one additional strain from the same phylogroup), and shared features (blue, detected in at least one additional strain from a different phylogroup).

Each bar in Figure 4B represents a single strain, with the number of detected features indicated on the y-axis. This number varies greatly among strains, with some talented strains standing out in terms of both total features and strain-specific features. Phylogroup C and, to a lesser extent, V2 were enriched in such strains. This is particularly relevant for phylogroup V2, for which all six strains shared an identical 16S rRNA sequence. In total, 36% of features were strain-specific, indicating that Planomonospora secondary metabolites tend to be strain-specific.

Because all 72 strains were cultivated in the same four media, feature distributions could be evaluated (see Figure 5). Overall, 57% of features were specific for a single medium. Media MC1 and R3, with 26 and 18% of exclusive features, respectively, were the biggest contributors. Furthermore, these two media covered 85% of all detected features. In contrast, just 9% of features were found in all media. Similar observations were made in a study of 26 marine Streptomyces strains, in which 71% of detected ions were medium-specific and just 7% common to all three conditions.14 Even though complete metabolite coverage remains elusive, our results suggest that two media should cover most of the metabolites produced by different Planomonospora strains belonging to different phylogroups.

Figure 5.

Visualization of the distribution of features in extracts with regard to cultivation medium. Media are MC1, AF2, R3, and AF. Overlaps amounting to less than 1% are not labeled.

Metabolite Annotation

The metabolites present in the Planomonospora metabolome were examined by first identifying known metabolites by dereplication.43,44 In addition to providing insights into the biosynthetic potential of this poorly studied genus, establishing the known metabolites can highlight features likely to be associated with novel chemistry, thus evading the pitfalls of reinvestigating reported compounds. As described below, representatives of 11 clusters were dereplicated, some of which are visualized in Figure 6. For annotation, both spectral matching (comparison with identified spectra in curated databases, such as GNPS) and literature search were used. To increase confidence in the annotations, Chemical Analysis Working Group (CAWG) criteria45 were applied, leading to a number of class 1 (comparison against an authentic standard) and class 2 (putatively identified molecule) annotations (for a full list, see Figure S4).

Figure 6.

Visualization of selected annotated clusters, with features annotated manually or by GNPS spectral library search (e.g., amphiphilic ferrioxamine 7). (A) Desferrioxamines (DFO) are mostly occurring in strains from phylogroup C. (B) Chymostatin-like metabolites show no phylogroup-specificity. (C) Siomycin and sphaericin are exclusive to phylogroup S.

Metabolites previously reported from Planomonospora were investigated. The lantibiotic 97518/planosporicin was identified in an extract from strain ID50037, after observing a signal with m/z 1096.89, which matched the [M + 2H]2+ ion of the compound. Comparison of the MS2 fragmentation spectrum to the one reported in the literature supported this assumption (see Figures S4 and S31).25 The lassopeptide sphaericin, identified by the signal m/z 2156.1, corresponding to the [M + H]+ ion, was found in the extracts of six strains.28 The MS2 fragmentation spectrum of the compound matched the one reported in the literature (see Figures S4 and S32). Furthermore, the thiopeptide siomycin A ([M + H]+ 1648.46 m/z), along with its congeners, siomycin B ([M + H]+ 1510.42 m/z), siomycin C ([M + 2H]2+ 832.73 m/z), and siomycin D1 ([M + 2H]2+ 817.73 m/z) was detected in extracts of up to 26 strains and are described in detail below. Finally, a signal with m/z 303.18, corresponding to the [M + 2H]2+ ion of ureylene-containing oligopeptide antipain, was detected in extracts of 11 strains and annotated by comparison to an authentic standard (see Figures S4 and S20). Several more signals belonging to ureylene-containing oligopeptides were identified: the antipain-like molecule KF 77AG6 ([M + H]+ 366.18 m/z, Figures S4 and S29) as well as chymostatin A/C ([M + H]+ 608.31 m/z, Figures S4 and S24) along with its congeners chymostatin B ([M + H]+ 594.30 m/z, Figures S4 and S25), chymostatinol A ([M + H]+ 596.32 m/z, Figures S4 and S26), chymostatinol B ([M + H]+ 610.33 m/z, Figures S4 and S27), and GE-20372 A/B ([M + H]+ 612.31 m/z, Figures S4 and S28). Except for thiostrepton, all previously reported Planomonospora metabolites were identified in the data set. In addition, several members of the desferrioxamine family, an iron chelating siderophore commonly produced by Streptomyces, were detected.46 The signal corresponding to desferrioxamine B [M + H]+ ion (561.36 m/z), detected in extracts of 8 strains, was annotated by comparison to a commercial standard (see Figures S4 and S30). Furthermore, signals matching acyl-desferrioxamine C13, C15, and C16 ([M + H]+ 729.54 m/z, [M + H]+ 757.58 m/z, and [M + H]+ 771.59 m/z, Figures S4 and S21–23, respectively) were identified by literature search. Some other putative siderophores were identified by spectral matching against the GNPS spectral library (see Figure S4): desferrioxamine E ([M + H]+ 601.36 m/z), as well as partially described metabolites deposited as amphiphilic ferrioxamine 7 ([M + H]+ 768.44 m/z), Bisu-05 ([M + H]+ 345.35 m/z), and Desf-05 ([M + H]+ 575.37 m/z).

Several of the dereplicated features showed strong phylogroup-specificity: The desferrioxamines were almost exclusively detected in samples from strains of phylogroup C (see Figure 6A), while siomycins and sphaericin were only detected in extracts derived from the S phylogroup strains (Figure 6C). Other metabolites were less phylogroup-specific: Chymostatinol A was produced by 31 strains from phylogroups C, S, V2, and A2, as were antipain (11 strains, phylogroups S, V2, and A2) or GE-20372 A/B (17 strains, phylogroups C, S, V2, and A2). Other identified ureylene-containing oligopeptides showed a similar broad distribution.

In total, 28 metabolites were annotated as CAWG classes 1 or 2 (see Figure S4). A summary of the presence/absence of all dereplicated features can be seen in Figure S5. Many more features in the molecular network are neighbors to annotated ones (and thus, structurally related). While a systematic investigation of all features would exceed the scope of this study, examples of special relevance will be discussed below. To get a better picture of the biosynthetic capacities of Planomonospora and to further explore the annotated metabolites, genomic analysis was used.

Genome Analysis

Public databases report two Planomonospora genome sequences: Planomonospora sphaerica JCM937447 and Planomonospora venezuelensis CECT3303, the latter not formally published yet. Three representative strains for full genome sequencing were selected: strain ID67723, as a representative of the divergent phylogroup V2 and for its capability to produce the oligopeptide antipain; strain ID82291, as the representative of a subgroup of strains in phylogroup A2 that produced the biarylitides, as reported in detail elsewhere;48 and strain ID91781, with its 16S rRNA sequence identical to that of P. sphaerica JCM9374 and a producer of the thiopeptide siomycin. Genomes were sequenced with both Illumina HiSeq and PacBio technologies to allow hybrid assembly, providing good quality sequences with a substantially lower number of contigs than that of the reference genomes of P. sphaerica JCM9374, P. venezuelensis CECT3303, and Planobispora rosea ATCC53733.49 The three genomes were similar to that of P. sphaerica JCM9374 and P. venezuelensis CECT330 and to each other in terms of GC content (from 71.5 to 72.8%, see Figure 7B). Interestingly, the genome of strain ID82291 was about 9% smaller than the other Planomonospora genomes and thus harbored a smaller number of predicted genes. antiSMASH analysis identified between 23 and 28 biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in the three genomes (see Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Overview of sequenced genomes, with comparison to reported ones. (A) Summary of metadata of newly sequenced genomes (bold type, P = Planomonospora). (B) Segment of autoMLST-generated phylogenetic tree. (C) Pairwise comparison of average nucleotide identity between the genomes, using the tool OrthoANIu.

A multilocus sequence analysis of the five strains of Figure 7A, along with other publicly available genome sequences of members of the Streptosporangiaceae, was performed with the web-based program autoMLST.50 Based on a concatenated alignment of 89 identified housekeeping genes (see Figure S38), a tree was constructed that was consistent with the one of Figure 2, except that strain ID91781 is now clearly distinct from Planomonospora sphaerica JCM9374 (see Figure 7B). Oddly, strain ID67723 and Planomonospora venezuelensis CECT3303 show a closer relationship to Planobispora rosea ATCC53733 than to the other Planomonospora strains, in contrast to the results from the 16S rRNA-based phylogeny (see Figure 2). Therefore, we calculated the average nucleotide identity (ANI) between the six genomes under investigation (see Figure 7C).51,52 An ANI of 95–96% is generally considered as species boundary cutoff.53,54 Only strain ID91781 and Planomonospora sphaerica JCM9374 showed a high enough ANI to fall in this category. Strain ID67723, Planomonospora venezuelensis CECT3303, and Planobispora rosea ATCC53733 appear to be slightly more similar to each other than to the other Planomonospora. While exceeding the scope of this study, these results warrant further studies in the taxonomy of Planomonospora and Planobispora ssp.

To investigate the similarity among the Planomonospora BGCs, the output of antiSMASH v5.0.08 was processed with the program BiG-SCAPE/CORASON v1.0. Based on Pfam composition, this tool calculates the similarity between BGCs and cluster related ones into gene cluster families (GCFs). BGCs that show low similarity to any other BGC are displayed as singletons. Therefore, BiG-SCAPE/CORASON allows for the quick access of phylogenetic relationships between BGCs. It further enables automatic annotation of BGCs using the MIBiG repository of experimentally established BGCs.55

The 155 BGCs from the genomes in Figure 7A could be grouped into 59 GCFs, of which 25 were singletons, as illustrated in Figure 8. Interestingly, the analysis demonstrated the existence of seven GCFs that are common among the five Planomonospora strains as well as Planobispora rosea ATCC53733. An additional GCF is present in all strains, except for ID82291, the strain with a slightly reduced genome, and one more in all strains except Planomonospora venezuelensis CECT3303. One GCF is present in the five Planomonospora genomes but not in Planobispora rosea. Only two of the seven core GCFs are highly related to experimentally established BGCs, namely, those for the lantipeptide catenulipeptin and for the polyketide alkylresorcinol. Some of these GCFs are highly conserved in other genomes of members of the Streptosporangiaceae (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Distribution of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in the genomes of five Planomonospora and one Planobispora strains. Newly sequenced strains are indicated in bold. The comparison is based on similarity between genes and gene clusters, calculated by the program BiG-SCAPE. BGCs with a similarity of more than 40% to a MIBiG-deposited gene cluster were annotated. For clusters without a MIBiG-annotation, the next most similar BGC is indicated (found in public genomes by ClusterBlast). The 11 Planobispora rosea singleton BGCs were omitted, as were one BGC of strain ID67723, one of P. sphaerica, and one of ID91781, fragmented due to their position on contig edges.

In addition to the core GCFs, strain ID67723, Planomonospora venezuelensis CECT3303, and Planobispora rosea ATCC53733 share one more GCF. Strain ID67723 and Planobispora rosea ATCC53733 share further six GFCs. This overlap includes an erythrochelin-like BGC, as discussed later. Furthermore, strains ID91781 and Planomonospora sphaerica JCM9374 are remarkably similar in terms of GCFs: ID91781 lacks the sphaericin BGC and another cluster of unknown function, present in Planomonospora sphaerica JCM9374, but instead contains a type I PKS BGC.

When compared to the MIBiG-repository, only 17 (31%) of all GCFs match an experimentally determined BGC. Investigation with the program ClusterBlast showed related BGCs in non-Planomonospora genomes. Similarities were low in the majority of cases, except for some of the core GCFs (see Figure 8).

In summary, the three analyzed genomes contain a considerable number of BGCs, with a core of BGCs present in several representatives of the Streptosporangiaceae family. In terms of BGCs, strain ID67723 appears to be very similar to Planobispora rosea ATCC53733, even though their ANI is relatively low. However, a larger number of genomes is needed to better understand the distribution of GCFs in Planomonospora, as demonstrated in studies on Planctomycetes(56) or Salinispora.15,16 Many of the BGCs in Planomonospora remain unannotated and may encode for novel metabolites. Aiming for a better understanding of the biosynthetic capabilities, we connected genomic and metabolomic data creating a “paired-omics” data set, as illustrated below.

Paired -Omics

Siomycin, first reported from Planomonospora in 1968 as sporangiomycin,24 is a thiostrepton-like thiopeptide with an established biosynthetic route.57 While the siomycin BGC was detected in strain ID91781 (RiPP4 in Figure 8), during metabolite annotation, it became evident that the features matching siomycin A and congeners B, C, and D1 were not clustered in a single cluster in the molecular network, as expected for structurally related molecules. Instead, they were mostly singletons, with MS2 spectra sufficiently different not to be clustered by the networking algorithm. However, inspection of the corresponding MS2 spectra revealed that siomycin A and congeners shared low molecular weight fragments, presumably corresponding to the quinalidic acid (QA) moiety of class b thiopeptides (see Figure S6). Hence, the program MS2LDA58 was used to mine for QA-related motifs in the MS2 fragmentation spectra of features. Apart from the known siomycins, the program detected an additional nine siomycin-like thiopeptides (see Figure S7). One, which we named siomycin E, is hypothesized to correspond to siomycin B with an additional dehydroalanine (Dha)-residue at its C-terminal end, instead of two, as in siomycin A. MS2-fragmentation spectra of the [M + H]+ ions showed a particular fragment corresponding to a break between Ala2 and Dha3 as well as Thr12 and QA, with an m/z-value diagnostic for each congener (see Figure 9 and Figure S8). Literature provides a precedent for a thiopeptide with a similar intermediate molecule: Thiopeptin A3a, A4a, and Ba have zero, one, and two Dha residues, respectively, at the C-terminal end of the molecule.59 The precursor peptide for thiopeptin, TpnA, indeed shows two serine moieties at the C-terminal end.60 Consistently, the precursor peptide encoded by the BGC RiPP4 contains two additional serine residues at the C-terminus (see Figure S9). Promiscuous processing of the C-terminal end of precursor peptides has been observed in several thiopeptides and can be also assumed here.57,59,61,62 For some of the other putative thiopeptides, the differences in exact mass with regard to siomycin A point toward the presence of one or two N-acetylcysteinyl-moieties with additional modifications, such as deacetylation or hydroxylation (see Figure S7). Again, literature provides precedence for likewise modified antibiotics from Streptomyces sp.: N-Acetylcysteine derivates have been isolated for the macrolide piceamycin63 and the phenazine SB 212021.64 These results show how the use of additional tools such as MS2LDA can overcome the limitations of any one tool and help to organize data, identify analogues, and support annotation (for a full list of annotated Mass2Motifs, see Figure S10).

Figure 9.

Identification and annotation of siomycin congeners. (A) Shows the putative tandem mass fragmentation pathway of siomycins, leading to the (B) diagnostic fragments. Siomycin A (blue) has two dehydroalanine (Dha)-moieties at its C-terminus end, while siomycin B (black) has none. Siomycin E (green) is hypothesized to be an intermediate congener with one Dha-group at its C-terminal end.

As mentioned above, several features were found to match desferrioxamines, iron-chelating siderophores involved in iron-uptake in bacteria,65,66 mostly in samples derived from strains of phylogroup C, raising the question of other Planomonospora strains producing distinctive iron-chelating molecules. In a study on 118 Salinispora genomes, Bruns et al. reported a mutually exclusive presence of either the des or slc BGC, responsible for the production of desferrioxamine or the structurally unrelated salinichelins, respectively.67 In order to rapidly identify iron-binding metabolites, we added FeCl3 to the Planomonospora extracts and reanalyzed them by LC-MS/MS, looking for mass shifts from the disappearance of the iron-free form and stabilization of the iron-bound molecule, with associated Fe-characteristic isotopic pattern. Apart from the already identified desferrioxamines, 18 features of four clusters were also affected by the addition of iron (see Figure 10A, Figures S12 and S14–S19). Calculation of molecular formulas and inspection of MS2-fragmentation spectra indicated relatedness between these four clusters but not to desferrioxamine E (see Figures S12 and S13). These four clusters were exclusive to seven strains belonging to phylogroups V2 and S. At the same time, no desferrioxamines could be detected in extracts from these strains. Analysis with BiG-SCAPE/CORASON suggested a candidate BGC (NRPS17 in Figure 8) in one of the producer strains, ID67723. This cluster showed high similarity to the experimentally validated BGC for erythrochelin, a siderophore produced by Saccharopolyspora erythraea, as well as to a BGC with unknown function from Planobispora rosea ATCC53733, as indicated in Figure 10B. Consistently, extracts from both strain ID67723 and Planobispora rosea contained a feature with m/z 631.3408 [M + H]+ with the calculated molecular formula C26H46N8O10 (see Figure 10A). Characterization of this metabolite confirmed a salinichelin-like structure, with a lysine instead of an arginine in position two (manuscript in preparation). For strain ID67723, 11 additional iron-shifted features were identified. The similarity of their MS2 fragmentation spectra to the features with m/z 631.3408 [M + H]+ suggests that they were also synthesized by BGC NRPS17. While many were hypothesized to be congeners differing in one or more methylene groups, feature ID314 (m/z 1067.5659) appears to be a glycosylated version of feature ID289 (m/z 905.5136).

Figure 10.

Investigation of some iron-binding metabolites: (A) Features in several clusters, such as m/z 631.3 or 843.4, showed iron complexion upon treatment with FeCl3. LCMS-analysis of Fe-treated samples shows disappearance of the unbound form (black trace) and appearance of the Fe-bound form (red trace; for original traces, see Figure S11). (B) Comparison of the erythrochelin BGC with GCF NRPS17, shared by Planomonospora strain ID67723 and Planobispora rosea ATCC53733.

Also for strain ID67723, a BGC similar to the experimentally validated BGC for deimino-antipain68 was detected (see NRPS24 in Figure 8 and Figure 11A). The compound antipain and several related ureylene-containing peptides, such as chymostatin A, were detected in the extracts from strain ID67723. The genomes of the other sequenced Planomonospora strains lacked this BGC, and indeed, antipain and related compounds could not be detected in their extracts. In the molecular network, the ureylene-containing compounds clustered together, as expected for structurally similar molecules (see Figure 6B). In addition to the annotated compounds, further 32 related but unknown features were found for strain ID67723 (see Figure 11B). We hypothesize that all these features originate from NRPS24, because for the deimino-antipain BGC, promiscuity in amino acid incorporation has been reported before.68 Related studies have shown that some single BGCs are capable to produce a variety of different molecules.69,70 While a detailed characterization of these molecules exceeds the scope of this study, the abundance of products resulting from a single BGC is worth noting.

Figure 11.

(A) Comparison between the biosynthetic gene cluster of deimino-antipain and NRPS24 from strain ID67723, performed with BiG-SCAPE/CORASON (cutoff value: 1). (B) Cluster containing antipain-related ureylene-containing compounds. Features detected for strain ID67723, likely to result from NRPS24, are indicated in red.

Conclusions

The work presented here provided unprecedented insight into the poorly explored genus Planomonospora. Among the 72 investigated strains, several were found to have yet unreported 16S rRNA sequences, phylogenetically distinct from previously known species. Using feature-based molecular networking, the majority of previously reported Planomonospora metabolites were found, demonstrating phylogroup-specificity for many of them. It was shown that Planomonospora can produce desferrioxamines as iron-chelating molecules, or, alternatively, members of an unknown siderophore family. With the help of different tools to organize MS2 data, we described a new congener of the siomycin family, siomycin E, and detected several other siomycin-like molecules that await further characterization. Furthermore, the recently described biarylitides, cyclic tripeptides with an unusual carbon–carbon biaryl bond, were prioritized from the features detected in the present study and are described in detail elsewhere.48 Still, the majority of features detected in the Planomonospora extracts remain unknown. Also, only 3 of the detected BGC could be linked to known products, which indicates great potential for the discovery of new specialized molecules. We conclude that investigations in this interesting genus have only just begun.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

LR-ESIMS data were acquired using a Dionex UltiMate 3000 HPLC system (Thermo Scientific) coupled to an LCQ Fleet (Thermo Scientific) mass spectrometer. Separation was achieved on an Atlantis T3 C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 mm × 50 mm) at a flow rate of 0.8 mL × min–1 and maintained at 40 °C. The injection volume was set at 10 μL. Elution was conducted with a 0.05% (v/v) TFA in H2O-MeCN gradient as follows: 0–1 min (10% MeCN), 1–7 min (10–95% MeCN), 7–12 min (95% MeCN). The ionization was carried out using an electrospray ionization source in the positive mode (range m/z 110–2000). HR-ESIMS spectra were recorded using a Dionex UltiMate 3000 HPLC system (Thermo Scientific) coupled to a micrOTOF III (Bruker) mass spectrometer. Separation was achieved on an Atlantis T3 C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 mm × 50 mm) at a flow rate of 0.3 mL × min–1 and maintained at 25 °C. The injection volume was set at 5 μL. Elution was conducted with a 0.1% (v/v) acetic acid in H2O-0.1% (v/v) acetic acid in MeCN gradient as follows: 0–1 min (10% MeCN), 1–20 min (10–100% MeCN), 20–26 min (100% MeCN). The ionization was carried out using an electrospray ionization source in the positive mode (range m/z 100–3000). All solvents and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Culturing, Extraction, and Sample Preparation

Planomonospora strains were cultivated from frozen stocks (−80 °C) on S1 plates71 at 28 °C for 2–3 weeks. The grown mycelium was then homogenized with a sterile pestle and used to inoculate 15 mL of AF (AF/MS)71 medium in a 50 mL baffled flask. After cultivation on a rotary shaker (200 rpm) at 30 °C for 72 h, 1.5 mL of the exponentially growing culture was used to inoculate each 15 mL of MC1 (35 g/L soluble starch, 10 g/L glucose, 2 g/L hydrolyzed casein, 3.5 g/L meat extract, 20 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L soybean meal, 2 g/L CaCO3, adjusted to pH 7.2), AF2 (8g/L yeast extract, 30 g/L soybean meal, 11 g/L glucose, 25 g/L malt extract, 1 g/L l-valine, 0.5 g/L Biospumex (Cognis, France), adjusted to pH 7.4), R3 (RARE3),72 and AF media in a 50 mL baffled flask.

After 7 days of cultivation, as before, 10 mL of each culture was centrifuged at 16 000 rcf for 10 min, and the resulting pellet was separated from the supernatant. For each culture, two different extracts were prepared: one by solvent extraction of the mycelium and one by solid-phase adsorption of the cleared broth. The mycelium was resuspended in 4 mL of EtOH and incubated under agitation at room temperature for 1 h. After centrifugation (16 000 rcf for 10 min), the pellet was discarded, and the mycelium extract was processed as described below. The cleared broth was stirred with 1 mL of HP20 resin suspension (Diaion) for 1 h at room temperature. The exhausted broth was discarded, and the loaded HP20 resin was stirred with 4 mL of purified water (Milli-Q, Merck); then, it was recovered by centrifugation and eluted with 5 mL of a 80:20 (v/v) mixture of MeOH and H2O under agitation at room temperature for 10 min. Both extracts were transferred to 96-well plates (conic bottom). For mycelium extract, 100 μL of extract were deposited, while for supernatant extract, 125 μL were deposited. Extracts were dried under vacuum at 40 °C. Using the same protocols, solvent blanks were generated.

Before LC-MS analysis, extracts were rehydrated: For mycelium extracts, 100 μL of a 90:10 (v/v) mixture of EtOH and H2O was used, while for supernatant extracts, 125 μL of a 80:20 (v/v) mixture of MeOH and H2O was utilized. The samples were centrifuged for 3 min at 16 000 rcf to remove suspended particles. Then, 50 μL of mycelium extract and 50 μL of supernatant extract, coming from a single culture, were combined, centrifuged for 3 min at 16 000 rcf, and transferred to HPLC vials for analysis. To test for iron-binding metabolites, 10 μL of 10 mg × mL–1 FeCl3 in water (Milli-Q, Merck) was added to selected rehydrated extracts.

Data-Dependent LC-ESI-MS/MS Analysis

For the 286 Planomonospora extracts investigated in molecular networking, data acquisition was performed on a micrOTOF-Q III (Bruker) instrument equipped with an electrospray interface (ESI), coupled to a Dionex UltiMate 3000 (Thermo Scientific) LC system, as described in the General Experimental Procedures. LC-ESI-HRMS/MS fragmentation was achieved in auto mode, with rising collision energy (35–50 keV over a gradient from 500 to 2000 m/z) with a frequency of 4 Hz for all ions over a threshold of 100. Calibration solution containing Na-acetate as internal reference mass (C2H3NaO2, m/z 83.0109) was injected at the beginning of each run.

For the analysis of commercial standards and selected Planomonospora extracts with added FeCl3, LC-MS analyses were performed on an LCQ Fleet (Thermo scientific) mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray interface (ESI), coupled to a Dionex UltiMate 3000 (Thermo Scientific) LC system, as described in the General Experimental Procedures and reported elsewhere.73

LC-ESI-HR-MS/MS Data Calibration and Conversion

LC-ESI-HR-MS/MS files were calibrated with Bruker DataAnalysis using an internal calibrant (Na-acetate) in HPC mode. The calibration was verified by inspection of medium component soyasaponin A, present in all samples (calc. [M + H]+m/z 943.526 at RT 12.7–12.9 min). Average mass deviation was routinely below 20 ppm. LCMS files were exported (see Figure S35) to the .mgf and .mzXML format with Bruker DataAnalysis (version 4.2 SR2 Build 365 64bit) and further processed using an ad hoc-written Perl5 script (see Figure S35 and S36). This was necessary for further processing with MZmine 2, because the export to the .mzXML format erroneously resulted in the insertion of the noncalibrated value in the precursor-entry (<precursorMz></precursorMz>) of each MS2-scan, leading to high mass deviations (>100 ppm) and disrupting the logical connection between MS1 and MS2 scans in the .mzXML files. The .mgf files were not affected by this, and thus, the script uses the correctly calibrated entries from the .mgf file to replace the noncalibrated entries in the .mzXML file.

Pre-Processing of HR-LC-MS/MS Data with MZmine 2

For preprocessing with MZmine 2 v51, .mzXML files were imported and subjected to the following workflow: (A) MassDetection = retention time, auto; MS1 noise level, 1E3; MS2 noise level, 2E1. (B) ADAP chromatogram builder74 = retention time, auto; MS-level, 1; min group size in no. of scans, 8; group intensity threshold, 5E2; min highest intensity, 1E3; m/z tolerance, 20 ppm. (C) Chromatogram deconvolution = baseline-cutoff algorithm; min peak height, 1E3; peak duration, 0.1–1.3 min; baseline level, 2.5E2; m/z range MS2 pairing, 0.02; RT range MS2 pairing, 0.4 min. (D) Isotopic peaks grouper = m/z tolerance, 20 ppm; RT tolerance, 0.2 min; monotonic shape, no; maximum charge, 2; representative isotope, most intense. (E) RANSAC peak alignment = m/z tolerance, 20 ppm; RT tolerance, 0.7 min; RT tolerance after correction, 0.35 min; RANSAC iterations, 100 000; minimum number of points, 50%; threshold value, 0.5; linear model, no; require same charge state, no. (F) Duplicate peak filter = filter mode, new average; m/z tolerance, 0.02 m/z; RT tolerance, 0.4 min. Features with no accompanying MS2 data were excluded from the analysis. Features present in both samples and media blanks were excluded, because they related to media components. Features with m/z-values of <300 or a retention time <1.5 min or >20 min were excluded. The resulting feature list contained 1492 entries and was exported to the GNPS-compatible format, using the dedicated “Export for GNPS” built-in options.

Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) Feature-Based Molecular MS/MS Network

Using the Feature-Based Molecular Networking (FBMN) workflow (version release_14)40 on GNPS,12 a molecular network was created by processing the output of MZmine 2. Parameters were adapted from the GNPS documentation: MS2 spectra were filtered so that all MS/MS fragment ions within ±17 Da of the precursor m/z were removed, and only the top 6 fragment ions in the ±50 Da window through the spectrum were utilized, with a minimum fragment ions intensity of 50. Both the MS/MS fragment ion tolerance and the precursor ion mass tolerance were set to 0.03 Da. Edges of the created molecular network were filtered to have a cosine score above 0.7 and more than 5 matched peaks between the connected nodes. Furthermore, these were only kept in the network if each of the nodes appeared in each other’s respective top 10 most similar nodes. The maximum size of clusters the network was set to 250, and the lowest scoring edges from each family were removed until member count was below this threshold. The MS2 spectra in the molecular network were searched against GNPS spectral libraries.12,75 Reported matches between network and library spectra were required to have a score above 0.6 and at least 5 matched peaks. The DEREPLICATOR-program was used to annotate MS/MS spectra.76 The molecular networks were visualized using Cytoscape 3.7.1.41 The molecular networking job is accessible by the link https://gnps.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/status.jsp?task=92036537c21b44c29e509291e53f6382. HR-ESI-LC-MS/MS data were deposited in MassIVE (MSV000085376) and linked with the genomic data at the iOMEGA Pairing Omics Data Platform (http://pairedomicsdata.bioinformatics.nl/projects).

MS2LDA Analysis

The molecular networking job described above was analyzed by MS2LDA (version release_14), accessing the tool directly on the GNPS website. Parameters were set as follows: bin width, 0.01; Nr of LDA iterations, 1000; min MS2 intensity, 100; LDA free motifs, 500. All MotifDBs except “Streptomyces and Salinispora Motif Inclusion” were excluded. Further parameters were left at default (overlap score threshold, 0.3; probability value threshold, 0.1; TopX in node, 5). Results were uploaded to the MS2LDA website, with the width of MS2 bins set to 0.005 Da, as recommended (http://ms2lda.org/).

16S rRNA Gene Amplification and Analysis

For 16S rRNA gene amplification, single colonies were picked from S1 medium plates and lysed at 95 °C in 100 μL of PCR-grade water for 5 min. Centrifuged lysate (5 μL) was added to the reaction mix, containing 25 μL of DreamTaq Green PCR Master Mix 2X (Thermo Scientific), 3 μL of 10x Denhardt’s reagents,77 each 500 nM of eubacterial primers R1492 and F27, and 12 μL water, resulting in a final volume of 50 μL. The amplification was performed as reported elsewhere.78 PCR products were sequenced using Sanger sequencing by an external service provider (Cogentech, Milan, IT), with the primers mentioned above. 16S rRNA gene sequences were inspected and assembled manually using the software AliView,79 yielding 35 nonredundant sequences with a consensus length of 1377 bp. The sequences were analyzed with programs contained in the PHYLIP package80 as reported elsewhere,78 with slight modifications (bootstrapped with 1000 replicates). The resulting consensus tree was visualized using the iTOL web server (https://itol.embl.de/).81 Sequences were deposited in GenBank, with accession numbers included in the Supporting Information (Figures S1–S2) of this study.

Isolation of gDNA

To isolate genomic DNA (gDNA), mycelium from 5 mL of Planomonospora cultures, cultivated in AF medium for 72 h as described above, was extracted with standard protocols for Streptomyces by phenol-chloroform, as described elsewhere.49 gDNA was sequenced with both Illumina and PacBio technologies by an external service provider (Macrogen, Seoul, KOR) and assembled using the program SPAdes (3.11). Genome sequences were deposited in GenBank under the BioProject ID PRJNA633779, with accession numbers JABTEX000000000 (ID82291), JABTEY000000000 (ID91781), and JABTEZ000000000 (ID67723).

Bioinformatics Analyses

For sequence similarity network analysis, BiG-SCAPE/CORASON 1.0 was used in “hybrids” mode, with all settings left to default, except the cutoff value, which was set to 0.5. The .gbk-files of BGCs detected by the web-based application antiSMASH 5.0 (https://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org/) were analyzed and compared to MIBiG-deposited BGCs. For phylogenetic multilocus sequence analysis, the web-based application autoMLST (http://automlst.ziemertlab.com/analyze#) was used in “denovo mode” with default settings. To calculate average nucleotide identity, the web-based application OrthoANIu (https://www.ezbiocloud.net/tools/ani) was used with default settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Christian Milani and Marco Ventura for genome reassembly and data curation, Paolo Monciardini for suggestions regarding the phylogenetic analysis, and the whole Naicons team for helpful comments and discussion. M.M.Z. thanks Prof. Tanneke den Blaauwen for guidance and advice. This work has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No.721484 (Train2Target). M.C. received funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG) grant no. CR464/7-1.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00807.

List of strains; schematic visualisation of feature finding and molecular networking; summary of features; table indicating presence/absence of identified features; quinalidic acid moiety of siomycin; list of identified siomycins, congeners, and related features; MS2-fragmentation spectra; comparison of thiopeptide precursor peptides; annotated MS2LDA-motifs; iron-complexion of metabolite; overview of putative siderophores; examples for similarities in tandem mass fragmentation between iron-complexing metabolites from different molecular families; iron-complexions; evidence for the annotation of the metabolite antipain; evidence for the annotations; transcript of Bruker method-file for the bulk export of .mzXML and .mgf-files; script for replacing uncalibrated precursor values in .mzXML-files with the calibrated ones from the .mgf-file; and genes considered for the multilocus sequence analysis (PDF)

Author Contributions

M.M.Z., M.S., and SD designed work, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. M.M.Z. performed all experimental work, including high resolution mass spectrometry analysis, and identified metabolites. M.I. and S.M. analyzed data and identified metabolites. M.C. performed high resolution mass spectrometry analysis and analyzed data.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): M.I., S.I.M., M.S., and S.D. are employees and/or shareholders of Naicons. M.M.Z. is a former employee of Naicons. M.C. declares that no competing interest exists.

Supplementary Material

References

- Newman D. J.; Cragg G. M. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83 (3), 770–803. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortholand J.-Y.; Ganesan A. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004, 8 (3), 271–280. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selva E. J. Antibiot. 2014, 67 (9), 613–617. 10.1038/ja.2014.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva R. R.; Dorrestein P. C.; Quinn R. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112 (41), 12549–12550. 10.1073/pnas.1516878112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfender J.-L.; Litaudon M.; Touboul D.; Queiroz E. F. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019, 36 (6), 855–868. 10.1039/C9NP00004F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yera E. R.; Cleves A. E.; Jain A. N. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54 (19), 6771–6785. 10.1021/jm200666a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimermancic P.; Medema M. H.; Claesen J.; Kurita K.; Wieland Brown L. C.; Mavrommatis K.; Pati A.; Godfrey P. A.; Koehrsen M.; Clardy J.; Birren B. W.; Takano E.; Sali A.; Linington R. G.; Fischbach M. A. Cell 2014, 158 (2), 412–421. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blin K.; Wolf T.; Chevrette M. G.; Lu X.; Schwalen C. J.; Kautsar S. A.; Suarez Duran H. G.; de los Santos E. L. C.; Kim H. U.; Nave M.; Dickschat J. S.; Mitchell D. A.; Shelest E.; Breitling R.; Takano E.; Lee S. Y.; Weber T.; Medema M. H. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45 (W1), W36–W41. 10.1093/nar/gkx319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kautsar S. A; Blin K.; Shaw S.; Navarro-Munoz J. C; Terlouw B. R; van der Hooft J. J J; van Santen J. A; Tracanna V.; Suarez Duran H. G; Pascal Andreu V.; Selem-Mojica N.; Alanjary M.; Robinson S. L; Lund G.; Epstein S. C; Sisto A. C; Charkoudian L. K; Collemare J.; Linington R. G; Weber T.; Medema M. H Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 48 (D1), D454–D458. 10.1093/nar/gkz882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. Y.; Sanchez L. M.; Rath C. M.; Liu X.; Boudreau P. D.; Bruns N.; Glukhov E.; Wodtke A.; de Felicio R.; Fenner A.; Wong W. R.; Linington R. G.; Zhang L.; Debonsi H. M.; Gerwick W. H.; Dorrestein P. C. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76 (9), 1686–1699. 10.1021/np400413s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox Ramos A. E.; Evanno L.; Poupon E.; Champy P.; Beniddir M. A. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019, 36 (7), 960–980. 10.1039/C9NP00006B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Carver J. J; Phelan V. V; Sanchez L. M; Garg N.; Peng Y.; Nguyen D. D.; Watrous J.; Kapono C. A; Luzzatto-Knaan T.; Porto C.; Bouslimani A.; Melnik A. V; Meehan M. J; Liu W.-T.; Crusemann M.; Boudreau P. D; Esquenazi E.; Sandoval-Calderon M.; Kersten R. D; Pace L. A; Quinn R. A; Duncan K. R; Hsu C.-C.; Floros D. J; Gavilan R. G; Kleigrewe K.; Northen T.; Dutton R. J; Parrot D.; Carlson E. E; Aigle B.; Michelsen C. F; Jelsbak L.; Sohlenkamp C.; Pevzner P.; Edlund A.; McLean J.; Piel J.; Murphy B. T; Gerwick L.; Liaw C.-C.; Yang Y.-L.; Humpf H.-U.; Maansson M.; Keyzers R. A; Sims A. C; Johnson A. R; Sidebottom A. M; Sedio B. E; Klitgaard A.; Larson C. B; Boya P C. A; Torres-Mendoza D.; Gonzalez D. J; Silva D. B; Marques L. M; Demarque D. P; Pociute E.; O'Neill E. C; Briand E.; Helfrich E. J N; Granatosky E. A; Glukhov E.; Ryffel F.; Houson H.; Mohimani H.; Kharbush J. J; Zeng Y.; Vorholt J. A; Kurita K. L; Charusanti P.; McPhail K. L; Nielsen K. F.; Vuong L.; Elfeki M.; Traxler M. F; Engene N.; Koyama N.; Vining O. B; Baric R.; Silva R. R; Mascuch S. J; Tomasi S.; Jenkins S.; Macherla V.; Hoffman T.; Agarwal V.; Williams P. G; Dai J.; Neupane R.; Gurr J.; Rodriguez A. M C; Lamsa A.; Zhang C.; Dorrestein K.; Duggan B. M; Almaliti J.; Allard P.-M.; Phapale P.; Nothias L.-F.; Alexandrov T.; Litaudon M.; Wolfender J.-L.; Kyle J. E; Metz T. O; Peryea T.; Nguyen D.-T.; VanLeer D.; Shinn P.; Jadhav A.; Muller R.; Waters K. M; Shi W.; Liu X.; Zhang L.; Knight R.; Jensen P. R; Palsson B. Ø; Pogliano K.; Linington R. G; Gutierrez M.; Lopes N. P; Gerwick W. H; Moore B. S; Dorrestein P. C; Bandeira N. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34 (8), 828–837. 10.1038/nbt.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Santen J. A.; Jacob G.; Singh A. L.; Aniebok V.; Balunas M. J.; Bunsko D.; Neto F. C.; Castano-Espriu L.; Chang C.; Clark T. N.; Cleary Little J. L.; Delgadillo D. A.; Dorrestein P. C.; Duncan K. R.; Egan J. M.; Galey M. M.; Haeckl F.P. J.; Hua A.; Hughes A. H.; Iskakova D.; Khadilkar A.; Lee J.-H.; Lee S.; LeGrow N.; Liu D. Y.; Macho J. M.; McCaughey C. S.; Medema M. H.; Neupane R. P.; O’Donnell T. J.; Paula J. S.; Sanchez L. M.; Shaikh A. F.; Soldatou S.; Terlouw B. R.; Tran T. A.; Valentine M.; van der Hooft J. J. J.; Vo D. A.; Wang M.; Wilson D.; Zink K. E.; Linington R. G. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5 (11), 1824–1833. 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crusemann M.; O’Neill E. C.; Larson C. B.; Melnik A. V.; Floros D. J.; da Silva R. R.; Jensen P. R.; Dorrestein P. C.; Moore B. S. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80 (3), 588–597. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan K. R.; Crüsemann M.; Lechner A.; Sarkar A.; Li J.; Ziemert N.; Wang M.; Bandeira N.; Moore B. S.; Dorrestein P. C.; Jensen P. Chem. Biol. 2015, 22 (4), 460–471. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemert N.; Lechner A.; Wietz M.; Millán-Aguiñaga N.; Chavarria K. L.; Jensen P. R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111 (12), E1130–E1139. 10.1073/pnas.1324161111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Männle D.; McKinnie S. M. K.; Mantri S. S.; Steinke K.; Lu Z.; Moore B. S.; Ziemert N.; Kaysser L. Msystems 2020, 5 (3), e00125–20. 10.1128/mSystems.00125-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug D.; Zurek G.; Revermann O.; Vos M.; Velicer G. J.; Müller R. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74 (10), 3058–3068. 10.1128/AEM.02863-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maansson M.; Vynne N. G.; Klitgaard A.; Nybo J. L.; Melchiorsen J.; Nguyen D. D.; Sanchez L. M.; Ziemert N.; Dorrestein P. C.; Andersen M. R.; Gram L. Msystems 2016, 1 (3), e00028–15. 10.1128/mSystems.00028-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monciardini P.; Iorio M.; Maffioli S.; Sosio M.; Donadio S. Microb. Biotechnol. 2014, 7 (3), 209–220. 10.1111/1751-7915.12123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiemann J. E. Microbiol. 1967, 15, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mertz F. P. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1994, 44 (2), 274–281. 10.1099/00207713-44-2-274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebata M.; Miyazaki K.; Otsuka H. J. Antibiot. 1969, 22 (8), 364–368. 10.7164/antibiotics.22.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiemann J.; Coronelli C.; Pagani H.; Beretta G.; Tamoni G.; Arioli V. J. Antibiot. 1968, 21, 525–531. 10.7164/antibiotics.21.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffioli S. I.; Potenza D.; Vasile F.; De Matteo M.; Sosio M.; Marsiglia B.; Rizzo V.; Scolastico C.; Donadio S. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72 (4), 605–607. 10.1021/np800794y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglione F.; Cavaletti L.; Losi D.; Lazzarini A.; Carrano L.; Feroggio M.; Ciciliato I.; Corti E.; Candiani G.; Marinelli F.; Selva E. Biochemistry 2007, 46 (20), 5884–5895. 10.1021/bi700131x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffioli S. I.; Monciardini P.; Catacchio B.; Mazzetti C.; Münch D.; Brunati C.; Sahl H.-G.; Donadio S. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10 (4), 1034–1042. 10.1021/cb500878h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodani S.; Inoue Y.; Suzuki M.; Dohra H.; Suzuki T.; Hemmi H.; Ohnishi-Kameyama M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 8, 1177–1183. 10.1002/ejoc.201601334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wingender W.; Hugo H. von; Frommer W.; Schäfer D. J. Antibiot. 1975, 28 (8), 611–612. 10.7164/antibiotics.28.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda H.; Aoyagi T.; Hamada M.; Takeuchi T.; Umezawa H. J. Antibiot. 1972, 25 (4), 263–265. 10.7164/antibiotics.25.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivon F.; Grelier G.; Roussi F.; Litaudon M.; Touboul D. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89 (15), 7836–7840. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothias L.-F.; Nothias-Esposito M.; da Silva R.; Wang M.; Protsyuk I.; Zhang Z.; Sarvepalli A.; Leyssen P.; Touboul D.; Costa J.; Paolini J.; Alexandrov T.; Litaudon M.; Dorrestein P. C. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81 (4), 758–767. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K. B.; Park E. J.; da Silva R. R.; Kim H. W.; Dorrestein P. C.; Sung S. H. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81 (8), 1819–1828. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b00292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K. B.; Woo S.; Ernst M.; van der Hooft J. J.J.; Nothias L.-F.; da Silva R. R.; Dorrestein P. C.; Sung S. H.; Lee M. Phytochemistry 2020, 173, 112292. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2020.112292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivon F.; Remy S.; Grelier G.; Apel C.; Eydoux C.; Guillemot J.-C.; Neyts J.; Delang L.; Touboul D.; Roussi F.; Litaudon M. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82 (2), 330–340. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b00800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivon F.; Retailleau P.; Desrat S.; Touboul D.; Roussi F.; Apel C.; Litaudon M. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83 (10), 3069–3079. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suriyachadkun C.; Ngaemthao W.; Chunhametha S. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66 (8), 3224–3229. 10.1099/ijsem.0.001178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaabane Chaouch F.; Bouras N.; Mokrane S.; Bouznada K.; Zitouni A.; Potter G.; Sproer C.; Klenk H.-P.; Sabaou N. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2017, 110 (2), 245–252. 10.1007/s10482-016-0795-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluskal T.; Castillo S.; Villar-Briones A.; Orešič M. BMC Bioinf. 2010, 11 (1), 395. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothias L.-F.; Petras D.; Schmid R.; Duhrkop K.; Rainer J.; Sarvepalli A.; Protsyuk I.; Ernst M.; Tsugawa H.; Fleischauer M.; Aicheler F.; Aksenov A. A.; Alka O.; Allard P.-M.; Barsch A.; Cachet X.; Caraballo-Rodriguez A. M.; Da Silva R. R.; Dang T.; Garg N.; Gauglitz J. M.; Gurevich A.; Isaac G.; Jarmusch A. K.; Kamenik Z.; Kang K. B.; Kessler N.; Koester I.; Korf A.; Le Gouellec A.; Ludwig M.; Martin C. H.; McCall L.-I.; McSayles J.; Meyer S. W.; Mohimani H.; Morsy M.; Moyne O.; Neumann S.; Neuweger H.; Nguyen N. H.; Nothias-Esposito M.; Paolini J.; Phelan V. V.; Pluskal T.; Quinn R. A.; Rogers S.; Shrestha B.; Tripathi A.; van der Hooft J. J. J.; Vargas F.; Weldon K. C.; Witting M.; Yang H.; Zhang Z.; Zubeil F.; Kohlbacher O.; Bocker S.; Alexandrov T.; Bandeira N.; Wang M.; Dorrestein P. C. Nat. Methods 2020, 17 (9), 905–908. 10.1038/s41592-020-0933-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P.; Markiel A.; Ozier O.; Baliga N. S.; Wang J. T.; Ramage D.; Amin N.; Schwikowski B.; Ideker T. Genome Res. 2003, 13 (11), 2498–2504. 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann T.; Krug D.; Bozkurt N.; Duddela S.; Jansen R.; Garcia R.; Gerth K.; Steinmetz H.; Müller R. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 803. 10.1038/s41467-018-03184-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert J.; Nuzillard J.-M.; Renault J.-H. Phytochem. Rev. 2017, 16 (1), 55–95. 10.1007/s11101-015-9448-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler J. A.; Alvarado A. B.; Schaufelberger D. E.; Andrews P.; McCloud T. G. J. Nat. Prod. 1990, 53 (4), 867–874. 10.1021/np50070a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner L. W.; Amberg A.; Barrett D.; Beale M. H.; Beger R.; Daykin C. A.; Fan T. W.-M.; Fiehn O.; Goodacre R.; Griffin J. L.; Hankemeier T.; Hardy N.; Harnly J.; Higashi R.; Kopka J.; Lane A. N.; Lindon J. C.; Marriott P.; Nicholls A. W.; Reily M. D.; Thaden J. J.; Viant M. R. Metabolomics 2007, 3 (3), 211–221. 10.1007/s11306-007-0082-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbert M.; Béchet M.; Blondeau R. Curr. Microbiol. 1995, 31 (2), 129–133. 10.1007/BF00294289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dohra H.; Suzuki T.; Inoue Y.; Kodani S. Genome Announc. 2016, 4 (4), e00779–16. 10.1128/genomeA.00779-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdouc M. M.; Alanjary M. M.; Maffioli S. I.; Crüsemann M.; Medema M. M.; Donadio S.; Sosio M. Cell Chem. Biol. 2021, 28, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tocchetti A.; Bordoni R.; Gallo G.; Petiti L.; Corti G.; Alt S.; Cruz J. C.; Salzano A. M.; Scaloni A.; Puglia A. M.; De Bellis G.; Peano C.; Donadio S.; Sosio M. PLoS One 2015, 10 (7), e0133705. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanjary M.; Steinke K.; Ziemert N. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47 (W1), W276–W282. 10.1093/nar/gkz282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I.; Ouk Kim Y.; Park S.-C.; Chun J. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66 (2), 1100–1103. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S.-H.; Ha S.-m.; Lim J.; Kwon S.; Chun J. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2017, 110 (10), 1281–1286. 10.1007/s10482-017-0844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goris J.; Konstantinidis K. T.; Klappenbach J. A.; Coenye T.; Vandamme P.; Tiedje J. M. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57 (1), 81–91. 10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M.; Rosselló-Móra R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106 (45), 19126–19131. 10.1073/pnas.0906412106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Muñoz J. C.; Selem-Mojica N.; Mullowney M. W.; Kautsar S. A.; Tryon J. H.; Parkinson E. I.; De Los Santos E. L. C.; Yeong M.; Cruz-Morales P.; Abubucker S.; Roeters A.; Lokhorst W.; Fernandez-Guerra A.; Cappelini L. T. D.; Goering A. W.; Thomson R. J.; Metcalf W. W.; Kelleher N. L.; Barona-Gomez F.; Medema M. H. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16 (1), 60–68. 10.1038/s41589-019-0400-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand S.; Jogler M.; Boedeker C.; Pinto D.; Vollmers J.; Rivas-Marín E.; Kohn T.; Peeters S. H.; Heuer A.; Rast P.; Oberbeckmann S.; Bunk B.; Jeske O.; Meyerdierks A.; Storesund J. E.; Kallscheuer N.; Lücker S.; Lage O. M.; Pohl T.; Merkel B. J.; Hornburger P.; Müller R.-W.; Brümmer F.; Labrenz M.; Spormann A. M.; Op den Camp H. J. M.; Overmann J.; Amann R.; Jetten M. S. M.; Mascher T.; Medema M. H.; Devos D. P.; Kaster A.-K.; Ovreas L.; Rohde M.; Galperin M. Y.; Jogler C. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5 (1), 126–140. 10.1038/s41564-019-0588-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao R.; Duan L.; Lei C.; Pan H.; Ding Y.; Zhang Q.; Chen D.; Shen B.; Yu Y.; Liu W. Chem. Biol. 2009, 16 (2), 141–147. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wandy J.; Zhu Y.; van der Hooft J. J J; Daly R.; Barrett M. P; Rogers S. Bioinformatics 2018, 34 (2), 317–318. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b van der Hooft J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113 (48), 13738–13743. 10.1073/pnas.1608041113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L.; Wang S.; Liao R.; Liu W. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19 (4), 443–448. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa H.; Bashiri G.; Kelly W. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (34), 10749–10756. 10.1021/jacs.8b04238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just-Baringo X.; Albericio F.; Alvarez M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53 (26), 6602–6616. 10.1002/anie.201307288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Liu W. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013, 30 (2), 218–226. 10.1039/C2NP20107K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz D.; Nachtigall J.; Riedlinger J.; Schneider K.; Poralla K.; Imhoff J. F.; Beil W.; Nicholson G.; Fiedler H.-P.; Süssmuth R. D. J. Antibiot. 2009, 62 (9), 513–518. 10.1038/ja.2009.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin M. L.; Fulston M.; Payne D.; Cramp R.; Hood I. J. Antibiot. 1995, 48 (10), 1081–1085. 10.7164/antibiotics.48.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keberle H. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1964, 119 (2), 758–768. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb54077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann G. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002, 30 (4), 691–696. 10.1042/bst0300691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns H.; Crüsemann M.; Letzel A.-C.; Alanjary M.; McInerney J. O.; Jensen P. R.; Schulz S.; Moore B. S.; Ziemert N. ISME J. 2018, 12 (2), 320–329. 10.1038/ismej.2017.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxson T.; Tietz J. I.; Hudson G. A.; Guo X. R.; Tai H.-C.; Mitchell D. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (46), 15157–15166. 10.1021/jacs.6b06848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinet L.; Naome A.; Deflandre B.; Maciejewska M.; Tellatin D.; Tenconi E.; Smargiasso N.; de Pauw E.; van Wezel G. P.; Rigali S. mBio 2019, 10 (4), e01230–19. 10.1128/mBio.01230-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegemann J. D.; Zimmermann M.; Xie X.; Marahiel M. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (1), 210–222. 10.1021/ja308173b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donadio S.; Monciardini P.; Sosio M. Methods Enzymol. 2009, 458, 3–28. 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)04801-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosio M.; Stinchi S.; Beltrametti F.; Lazzarini A.; Donadio S. Chem. Biol. 2003, 10 (6), 541–549. 10.1016/S1074-5521(03)00120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio M.; Tocchetti A.; Santos Cruz J. C.; Del Gatto G.; Brunati C.; Maffioli S. I.; Sosio M.; Donadio S. Antibiotics 2018, 7 (2), 47. 10.3390/antibiotics7020047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers O. D.; Sumner S. J.; Li S.; Barnes S.; Du X. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89 (17), 8696–8703. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horai H.; Arita M.; Kanaya S.; Nihei Y.; Ikeda T.; Suwa K.; Ojima Y.; Tanaka K.; Tanaka S.; Aoshima K.; Oda Y.; Kakazu Y.; Kusano M.; Tohge T.; Matsuda F.; Sawada Y.; Hirai M. Y.; Nakanishi H.; Ikeda K.; Akimoto N.; Maoka T.; Takahashi H.; Ara T.; Sakurai N.; Suzuki H.; Shibata D.; Neumann S.; Iida T.; Tanaka K.; Funatsu K.; Matsuura F.; Soga T.; Taguchi R.; Saito K.; Nishioka T. J. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 45 (7), 703–714. 10.1002/jms.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohimani H.; Gurevich A.; Shlemov A.; Mikheenko A.; Korobeynikov A.; Cao L.; Shcherbin E.; Nothias L.-F.; Dorrestein P. C.; Pevzner P. A. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9 (1), 4035. 10.1038/s41467-018-06082-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volossiouk T.; Robb E. J.; Nazar R. N. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61 (11), 3972–3976. 10.1128/AEM.61.11.3972-3976.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monciardini P.; Sosio M.; Cavaletti L.; Chiocchini C.; Donadio S. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2002, 42 (3), 419–429. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson A. Bioinformatics 2014, 30 (22), 3276–3278. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J.PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package), Version 3.5c; Felsenstein J., 1993.

- Letunic I.; Bork P. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47 (W1), W256–W259. 10.1093/nar/gkz239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.