Abstract

Objective

The transition from paediatric to adult medicine involves risks of poor patient outcomes and of significant losses of patients to follow up. The research aimed to analyse the implementation in an initial cohort of patients of a new programme of transition to adult care based on a case management approach.

Design

A longitudinal study of the case management approach to transition, initiated in a university hospital in France in September 2016.

Methods

Patients with the endocrine or metabolic disease diagnosed during childhood and transferred to adult care were included. The transition programme includes three steps based on case management: liaising with paediatric services, personalising care pathways, and liaising with structures outside the hospital (general practitioners, agencies in the educational and social sector).

Results

The cohort included 500 patients, with malignant brain tumour (n = 56 (11%)), obesity (n = 55 (11%)), type 1 diabetes (n = 54 (11%)), or other disease (n = 335 (67%)). Their median age at transfer was 19, and the sex ratio was 0.5. At median 21 months of follow-up, 439 (88%) had a regular follow-up in or outside the hospital, 47 (9%) had irregular follow-up (absence at the last appointment or no appointment scheduled within the time recommended), 4 had stopped care on doctor’s advice, 4 had died, 3 had moved, and 3 had refused care. The programme involved 9615 case management actions; 7% of patients required more than 50 actions. Patients requiring most support were usually those affected by a rare genetic form of obesity.

Conclusions

Case managers successfully addressed the complex needs of patients. Over time, the cohort will provide unprecedented long-term outcome results for patients with various conditions who experienced this form of transition.

Keywords: transition to adult care, endocrinology, case management, cohort, care pathway, rare diseases

Introduction

Metabolic and endocrine diseases in children and adolescents include more than 500 different diseases with an overall incidence of between 1:2000 and 1:4000 (1). The most common condition is type 1 diabetes, which has an incidence of about 15 cases per 100,000 children under the age of 15 (2), while the rarest have reporting incidences of less than one in every 1,000,000 children. These diseases differ according to the type of involvement (isolated or multisystemic), the organs affected, the age of disclosure and the need for paramedical or social care and support.

In recent decades, the survival rate of these paediatric patients has improved, and their care pathway now involves a transition to adult care around their age of majority. In the literature, this period is associated with poor outcomes that have various consequences for the health of young people: poor clinical results, disruptions of care, visits emergency departments, hospitalisations and intensive care admissions, especially in endocrine diseases (3, 4). In addition, patients and families report low satisfaction with care and increased psychological distress during the transition (5).

For patients, in particular young people with various endocrine and metabolic diseases (6), the transfer to adult care represents a major challenge. In paediatric care, young people generally have a long-standing relationship and are comfortable with a team familiar with their illness and with their personal and social history; however, consultations do not always adapt to meet the needs of adolescents and to encourage their empowerment (7). Patients in adult care, who are considered autonomous, may consult a different caregiver at each visit, while consultations focus mainly on clinical outcomes and do not always address the psychosocial or developmental concerns of young people. Poorly prepared for the management of these paediatric patients, adult specialists may neglect the pathological part of the child and its consequences, both physical and psycho-social (8).

To deal with this situation, recommendations have been developed internationally to support the successful transition from paediatric to adult care (9, 10, 11). However, most of the content of these recommendations focuses on paediatric preparation. They advocate ongoing information about transition throughout the care pathway, inclusion of the family, consideration of developmental aspects, patient education and specific resources, coordination with primary care, and flexible adaptation of the moment of transfer to the individual case. Several programs have been developed and published, showing that a prepared and coordinated transition can have a positive impact on patients’ health, their experiences of care and the use of care. In a systematic review published in 2017, only 6 of the 39 (12) identified transition programs were delivered in adult services (13), and 5 were dedicated exclusively to young people with type 1 diabetes. The same review showed that programs developed for a specific pathology may be appropriate for young people with various diseases. The published programs are generally accessible only to some individuals on the active patient list: 20% of programs exclude young people with an intellectual disability (13). Finally, the timing of data collection after patient transfer enables assessment of the short- and medium-term outcomes of the interventions, but rarely of longer-term ones (13).

It is in this context that a new programme of transition based on case management has been developed in a French adult hospital for young people with various endocrine and metabolic diseases. The development project was based on a survey, conducted by the team involved, of the difficulties faced during transition by young adults with congenital adrenal hyperplasia, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and growth hormone deficiency (14). The need for development of such a programme was reinforced by a second survey showing an association between successful transition to specialist adult care and better health-related quality of life and regular medical follow-up in adulthood (15). The very large number of patients shown to be lost to follow up in this study motivated the development of the TRANSEND project to reconsider the organisation of transition to adult care. Although these surveys focused on specific pathologies, the conclusions and implications that could be drawn concerned a larger group of patients; the TRANSEND project was therefore developed to meet the needs of all chronically ill patients during the transition rather than the specific requirements of a particular disease.

In the light of these observations, the objective was twofold: firstly to implement a transition programme in an adult care department that meets the needs of patients and fulfils the recommendations, and secondly to collect data on a large number of patients in transition to study their long-term outcomes.

The TRANSEND programme takes place in an adult hospital (hospital de la Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France) in the endocrinology, nutrition and diabetology departments. The steering committee (made up of doctors from the three departments involved) defined the TRANSEND programme as a dedicated care pathway for patients in transition, where a case manager has a central role in adapting and coordinating for each patient, from their discharge from paediatric services to their strong attachment in adult services.

The specific objective of the present study was to describe the initial cohort of patients and analyse their experience of a transition managed under the new programme based on a case management approach.

Materials and methods

Patients

All the patients cared for by hospital-based paediatricians in transition to adult care, aged less than 25 at transfer and referred to services of nutrition, diabetology or endocrinology (metabolism, reproduction, thyroid and endocrine tumours) were included in the transition programme and constitute the study cohort. The study is reported according to the STROBE Statement (16) (Supplementary material 1, see section on supplementary materials given at the end of this article).

Description of the transition program

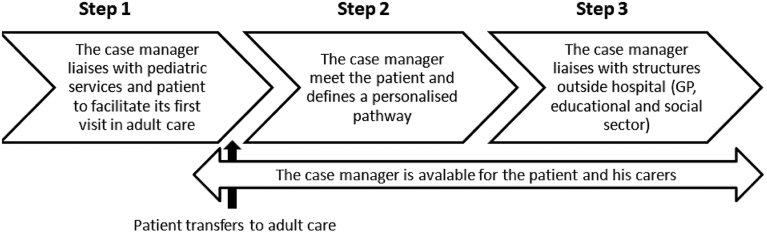

A medical steering committee for the TRANSEND programme development was created comprising the doctors from the nutrition, diabetology, and endocrinology services. Meetings and informal interviews were carried out with all the professionals of these services involved in the transition (nurses, social workers, psychologists, dieticians, medical secretaries). The information and opinions collected have been combined with the findings of surveys carried out in the department, to define a care pathway for patients in transition. This development phase was done in parallel with the recruitment of the case manager. The developed programme involved three steps based on case management (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the TRANSEND care pathways.

Step 1 is dedicated to liaising with paediatric services and patients to facilitate the patient’s first visit to adult care (transfer of the file, call-up of the patient, file presentation by transition staff).

Step 2 defines the care pathway in adult service. Upon arrival in the adult service, patients coming from paediatrics systematically meet the case manager and their new doctors. The meeting takes place in a dedicated TRANSEND room, youth-friendly and adapted to all types of mobility and bodily need. The case manager assesses the needs of each patient using interview and questionnaires (on social needs, patients’ expectations and patients’ autonomy) to offer them a personalised pathway in the hospital involving the different available resources and professionals (medical, paramedical, social). Throughout the follow-up, care pathways are supervised by the case manager, who is identified as the key contact by the patients, and who is reachable by text, phone or mail.

Step 3 focuses on liaising with structures outside the hospital (general practitioner, agencies in the educational and social sectors), to improve the long-term follow-up of patients, and to enhance wide-scale coordination of the life project (ensuring that the patient has appropriate training and employment, a suitable place to live, social activities). (See all the details of the care approach in TidiER checklist (17) – Supplementary material 2.)

The programme was launched in September 2016, with a full-time case manager and a dedicated place in the adult hospital concerned. The programme is dynamic and has evolved each year since its launch, the evolutions are discussed and decided with the steering committee. Additional elements based on the observation of patients’ needs have been added over time: additional time dedicated to coordination, creation of explanatory leaflets about patients’ diseases intended for professionals outside the hospital, dedicated therapeutic education sessions, questionnaires that allow to complete the tools available for the patients’ needs’ assessment (questionnaire to define patient expectations developed specifically for the program, questionnaire to assess patients’ autonomy using the Good2Go (18)).

Data collection and statistical analysis

The data used were collected as part of the case manager’s routine activity of monitoring and filing activity reports. The sources of data are the patient’s medical file and the case report form used by the case manager in routine collection of all the individual data of the patients related to their arrival and follow-up in the TRANSEND programme prospectively. These data are summarised and not identifiable, and their collation does not require Institutional Review Board approval according to European or French regulations (Regulation (Eu) 2016/679 Of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)).

A descriptive analysis was conducted on the data collected between the launch of the programme in September 2016 and the first interim analysis realised in March 2020. Results were reported as median (Q1, Q3) for continuous variables and as frequency counts and percentages (%) for categorical variables.

Results

Since its launch, 500 patients have experienced the TRANSEND programme (patients with at least one visit). The distribution of the first visits in the programme per year has been consistent in time: 144 took place in the first year of the launch, 134 in the second year, 140 in third year, and 82 during the first half of the fourth year. The mean follow up time in the programme is 21 months (min: 0; max: 42). The majority of patients make their transition from a hospital at a regional level (471/500, 94%), 14 from a hospital outside the regional level, 11 from a private practitioner, and 4 from the social or voluntary sector. Patients included in the programme had more than 15 different medical conditions; the main diagnoses and patients’ health characteristics are presented in Table 1. Patients had diverse socio-demographic profiles (Table 2) resulting in complex and diverse needs for support. Over the period, the case manager performed 9615 coordination actions, from 1 to 461 per patient. These involved meetings, telephone conversations and emails, with the patient, the family, and intra- and extra-hospital partners. Actions relating to the TRANSEND programme (call before first visit, plan and deliver the first meeting between patient and case manager) and to the link with paediatrics (request for medical records), represent 2734 (28%) of coordination actions. Management of hospital appointments (consultations with a doctor or other professional, hospitalisations, delay or postponement of appointments, reminders in case of appointments not scheduled or not attended, requests for transportation vouchers, admission procedures, information on hospital and services, etc.) represent 3389 (35%) of coordination actions. Follow-up of patients (medical issues, social issues, links with community/private practice, other hospitals, medical-social establishments, paramedical, organisation of neuropsychological assessments) represent 3492 (36%) of coordination actions.

Table 1.

Cohort medical characteristics.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Diseases | |

| Malignant brain tumour (except craniopharyngioma) | 56 (11) |

| Obesity | 55 (11) |

| Type 1 diabetes | 54 (11) |

| Congenital hypopituitarism | 43 (9) |

| Disorders of pubertal development | 41 (8) |

| Thyroid diseases | 38 (8) |

| Prader–Willi syndrome | 35 (7) |

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia | 27 (5) |

| Turner syndrome | 22 (4) |

| Growth delay | 18 (4) |

| Non congenital hypopituitarism | 17 (3) |

| Craniopharyngioma | 16 (3) |

| Familial dyslipidemia | 8 (2) |

| Other conditions (rare diseases, pituitary benign tumour, patients at risk following disease or treatment) | 70 (14) |

| Pre-transfer referral | |

| Hospital paediatrician | 474 (95) |

| Hospital adult specialist | 11 (2) |

| Private practice paediatrician | 7 (1) |

| General practionner | 4 (1) |

| Social or associative sectors professional | 4 (1) |

Table 2.

Cohort socio-demographic characteristics.

| Med (Q1–Q3) | |

|---|---|

| Age the first appointment | 19 (17–20) |

| Sex | n (%) |

| Male | 250 (50) |

| Female | 250 (50) |

| Place of residence | |

| Parents’ home | 423 (85) |

| Self home | 52 (10) |

| Medico-welfare establishment | 22 (4) |

| Other | 3 (<1) |

| Scholarship or professional status (MD = 13) | |

| Post graduate studies | 199 (40) |

| High school or vocational school | 117 (23) |

| Medico-pedagogic institute | 91 (18) |

| No activity | 39 (8) |

| Ordinary work | 33 (7) |

| Adapted to disability work | 4 (<1) |

MD, missing data.

For the 33 (7%) patients whose transition required more than 50 actions, a median of 82 actions were performed. Of these patients, 20 (61%) have obesity (the majority having a rare genetic form of obesity).

The case manager planned care with a dietician for 148 (30%) patients, with a psychologist for 95 (20%) patients, and with a social worker for 44 (9%) patients. Patient education, in groups, was delivered to 34 (8%) patients. A third of patients (n = 156) had a second individual facilitation meeting with the case manager, at the request of the doctor, especially during hospitalisation. Of the 500 patients in the cohort, 416 (83%) have regular follow-up in the hospital (next consultation already scheduled and/or within the recommended time limit for the next consultation), 23 (5%) are being followed in another hospital or in a private practice, 47 (9%) have irregular follow-up (absence at the last appointment or no appointment scheduled within the time recommended by the doctor), 4 have stopped care in a hospital setting on the doctor’s advice, 4 have died (3 fatal outcomes of a brain tumour, 1 accident related to an epilepsy seizure), 3 have moved, and 3 have refused care. Among those with regular or irregular follow-up, 149 (30%) were called once or several times to unattended and/or unplanned appointments. Among these patients, 86 (58%) scheduled a new appointment. The reasons given for the irregularity of the follow-up were resistance to medical follow-up (asymptomatic or sceptical patients), concerns linked to life projects (studies, work, their sociology-medical support agency) or to other medical care (oncology, psychiatry, neurology, etc.) and social and family difficulties (no parental support, lack of autonomy). No diagnosis is clearly overrepresented in these patients.

Discussion

In 3 years of activity, the TRANSEND programme has demonstrated the possibility of sharing of resources between different services and the acceptance by all professionals in an adult care department of a new organisation and a new worker (the case manager) to improve transition care by providing coordination of care and adapting support to the needs of the patients. The programme acceptance is supported by the fact that all patients arriving in this department have been referred to the case manager since the launch of the program, regardless of the doctor in charge. This acceptance is probably enhance by the fact that the TRANSEND programme has developed in response to a locally identified need: that of young patients lost to follow-up during transition (14, 15). The acceptability has also been probably strengthened by the involvement of the professionals of the department since the beginning in the steering committee, which developed and made the TRANSEND programme evolve. The TRANSEND programme was developed based on the needs of young patients identified in the international literature, which found a lack of awareness of psychosocial and developmental aspects and coordination in adult care (19) but also based on the local needs of young people, relying on local surveys. The programme is based on a patient-centred care approach. The case manager and overall organisation enable provision of care that is respectful of, and responsive to, individual patient preferences, needs and values (20). It follows international recommendations on transition by providing information about transition, including to patients’ families, considering the developmental aspects, allowing access to patient education and specific resources, and coordinating with primary care; these are particularly valuable and rare in routine adult medical care.

To our knowledge, the TRANSEND cohort is the largest and the most diversified in terms of patient profile in the field of transition. This cohort, whose data are collected routinely, reflects the real life of the programme outside any interventional framework. The cohort study will be enriched over the years with other data (care use, self-management, and satisfaction) and new patients. It will result in longer-term study of young people with multiple diseases in post-transition, and identification of factors linked to long term outcomes and unmet needs to inform the evolution of TRANSEND. This continuous improvement of the programme is already in progress, based on questionnaire completion by patients who report their needs to the case manager. Lastly it also enables the identification of the young patients’ need for more exchange between them.

The TRANSEND programme includes patients with various diseases, with or without intellectual disability or in socially complex situations, which will ensure a high external validity for its results. The choice to build a cohort allows for equity in access to quality care. In clinical trials one of the constraints is to select a homogeneous population to gain in precision (often at the expense of patients with complex profiles); this cohort study makes it possible to systematically include the patients followed in the department and subsequently to study all patient profiles, their different needs in terms of accompaniment during transition, and their long term outcomes. Although the transition programme offered to patients in this cohort is intended to be universal, a limit is observed. A subgroup of patients in the cohort requires a large number of time consuming actions from the case manager, which was not planned at the outset: a variation of the programme to better adapt to the different patient profiles could be considered.

According to a systematic review published in 2016, there is a lack of data from prospective studies on adult care attendance by patients in transition, and few studies have reported attendance in adult care at more than one year after transfer (21). In a retrospective study of congenital adrenal hyperplasia patients, 50% were lost to follow-up after transfer to adult care, with no difference between those who transitioned through a young person clinic and those who did not (22). The same rate was reported in our department before the implementation of the TRANSEND programme in patients with this same disease (15). In another study evaluating the effect of an endocrinology transition clinic for patients with diverse diseases, adherence to adult care was 83% (23). In diabetes care, a recent literature review reported that in the absence of a formal transition process for patients with type 1 diabetes, the proportion of patients lost to follow up is reported as between 11% and 62% (24). Although data collection methods, post-transfer evaluation times, and definitions of ‘patient lost to follow up’ are heterogeneous and make comparison difficult, the continued attendance rate reported in the TRANSEND cohort is much higher than those reported in the literature on young adults with endocrine and metabolic diseases.

A key issue in transition programs is their financial sustainability (25). With 500 active patients the case manager works full-time. The timing of patient exit from the program, initially planned when the patient is 25 years old, seems to have to adapt to the patient’s needs. Prioritisation of actions and tasks delivered by the case manager becomes needed with the growth in numbers of patients in the cohort. For example, the necessary coordination with professionals outside TRANSEND remains a challenge: the involvement of private practice medicine, the handover in hospital services and links with paramedics remain fragile after several years of existence of the program. The upcoming evaluation of the costs associated with the programme and also of savings (including savings of costs of avoidable care) will help to better inform the relevance and cost–benefit analysis of the program.

The principle of equivalence would not have been respected if the impact of TRANSEND was evaluated in a randomised trial against usual forms of care. Previous usual care practice did not adapt to the situation of transition or to young adults’ specific needs. Given the reported data on morbidity and mortality associated with interruptions of care during transition (26), it did not seem ethical to expose the patients of a control group to additional risks of serious or irreversible damage from not receiving an intervention based on recommendations.

However, a comparative non-randomised evaluation of TRANSEND is currently underway. It compares the post-transition outcomes in patients who transferred to adult care before TRANSEND to those who transferred after its implementation and benefited from it. The evaluation is based on the set of successful transition consensual indicators (27) as well as a medico-economic assessment.

To conclude, the TRANSEND cohort shows that case-management upon arrival in adult care enhances satisfactory results with regard to follow-up after transfer from paediatrics: 88 % have regular follow-up and only 4 patients in 500 are confirmed as lost to follow-up (0.6%). Achieving these results involved significant deployment of resources: nearly 10,000 actions of case-management have been performed for the entire cohort.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

The transition programme (dedicated room and case-manager funding) was supported by the ‘Hôpitaux de Paris – Hôpitaux de France’ Foundation (‘Transition program’ Grant, 2015). The realisation and analysis of the cohort did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the nurses, social workers, dieticians, psychologists, and medical secretaries from the departments involved in the TransEND cohort for participating in the elaboration of the program. The authors also like to thank Mrs E Benmansour, Mr S Morel, previous directors of Pitié Salpêtrière Hospital for their support for our proposal to set up such a program. Finally, the authors would like to thank Pr A Basdevant, Mr F Le Magny and Referis consultants for their advice in building up this program. The Transend group includes all those doctors who refer their patients to the programme and/or follow them in adult care: Prs and Drs. Afenjar, Aigrain, Amoura, Amouyal, Amsellem Jager, An, Andreelli, Azar, Bachelot, Belien Pallet, Beltrand, Bibal, Bidet, Bismuth, Blanc, Bodemer, Bougneres, Bourron, Bouvattier, Brauner, Brioude, Bruckert, Brugieres, Brune, Brunel, Burggraeve, Cabrol, Cacoub, Carel, Carlier, Carreau, Cassuto, Cessans, Chakhtoura, Cheikhelard, Chevignard, Ciangura, Consoli, Couderc, Coupaye, Courtillot, Da Costa, Dabbas, Dalla Vale, Dassa, De Beaufort, De Kerdanet, Delanoe, Delcroix, Diene, Dierick-Gallet, Donadieu, Dormoy, Doummar, Doz, Dubern, Dufour, Duranteau, Esteva, Fayech, Fiot, Flandrin, Flechtner, Fresneau, Gajdos, Gallo, Gaspar, Gelwane, Ghander, Giabicani, Gonzalez, Grill, Guilmin-Crepon, Grouthier, Hartemann, Haye, Heide, Houang, Ibrahim, Idbaih, Istanbullu, Jacqueminet, Jacquin, Jeandidier, Jeannin, Karsenty, Kenigsberg, Kipnis, Le Bastard, Le Poullenec, Leenhardt, Lefevre, Loison, Lorenzini, Lucidarme, Ly, Manh, Martinerie, Masson, Meneret, Mignot, Milcent, Mircher, Mochel, Moretti, Mosbah, Mourre, Moutafoff-Borie, Muller, Nasser, Navarro, Pasqualini, Paulsen, Pauwels, Personnier, Phan, Piquard Mercier, Porquet-Bordes, Puget, Ribeiro Parenti, Ricour, Rigaux, Robert, Robin, Rougeoreille Cretier, Samara Boustani, Sarnacki, Sauvion, Semeraro, Simon, Storey, Thalassinos, Tounian, Trang, Tubiana-Rufi, Villanueva, Whalen, Zaarour, Zenaty.

References

- 1.Saudubray J-M, Sedel F.Les maladies héréditaires du métabolisme à l’âge adulte. Annales d’Endocrinologie 2009. 70 14–24. ( 10.1016/j.ando.2008.12.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyürüs E, Green A, Soltész G.EURODIAB Study Group. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989–2003 and predicted new cases 2005–20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet 2009. 373 2027–20. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(0960568-7)) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lotstein DS, Seid M, Klingensmith G, Case D, Lawrence JM, Pihoker C, Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Gilliam LK, Corathers Set al. Transition from pediatric to adult care for youth diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in adolescence. Pediatrics 2013. 131 e1062–e1070. ( 10.1542/peds.2012-1450) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cadario F, Prodam F, Bellone S, Trada M, Binotti M, Trada M, Allochis G, Baldelli R, Esposito S, Bona Get al. Transition process of patients with type 1 diabetes (T1DM) from paediatric to the adult health care service: a hospital-based approach. Clinical Endocrinology 2009. 71 346–3. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03467.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hepburn CM, Cohen E, Bhawra J, Weiser N, Hayeems RZ, Guttmann A.Health system strategies supporting transition to adult care. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2015. 100 559–5. ( 10.1136/archdischild-2014-307320) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polak M, Touraine P.eds). Transition of Care: From Childhood to Adulthood in Endocrinology, Gynecology, and Diabetes [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 16]. (Endocrine Development; vol. 33). S. Karger AG, 2018. (available at: https://www.karger.com/Book/Home/277185) [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Staa AL, Jedeloo S, van Meeteren J, Latour JM.Crossing the transition chasm: experiences and recommendations for improving transitional care of young adults, parents and providers. Child: Care, Health and Development 2011. 37 821–8. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01261.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monaghan M, Hilliard M, Sweenie R, Riekert K.Transition readiness in adolescents and emerging adults with diabetes: the role of patient-provider communication. Current Diabetes Reports 2013. 13 900–90. ( 10.1007/s11892-013-0420-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians & American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics 2002. 110 1304–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canadian Paediatric Society & Adolescent Health Committee. Transition to adult care for youth with special health care needs. Paediatrics and Child Health 2007. 12 785–7. ( 10.1093/pch/12.9.785) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh SP, Anderson B, Liabo K, Ganeshamoorthy T.Guideline Committee. Supporting young people in their transition to adults’ services: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2016. 353 i2225. ( 10.1136/bmj.i2225) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabriel P, McManus M, Rogers K, White P.Outcome evidence for structured pediatric to adult health care transition interventions: a systematic review. Jurnalul Pediatrului 2017. 188 263, .e15–269.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Roux E, Mellerio H, Guilmin-Crépon S, Gottot S, Jacquin P, Boulkedid R, Alberti C.Methodology used in comparative studies assessing programmes of transition from paediatrics to adult care programmes: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2017. 7 e012338. ( 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012338) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godbout A, Tejedor I, Malivoir S, Polak M, Touraine P.Transition from pediatric to adult healthcare: assessment of specific needs of patients with chronic endocrine conditions. Hormone Research in Paediatrics 2012. 78 247–2. ( 10.1159/000343818) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bachelot A, Vialon M, Baptiste A, Tejedor I, Elie C, Polak M, Touraine P.Impact of transition on quality of life in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia diagnosed during childhood. Endocrine Connections 2017. 6 422–42. ( 10.1530/EC-17-0094) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP.STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007. 370 1453–145. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(0761602-X)) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, Altman DG, Barbour V, Macdonald H, Johnston Met al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014. 348 g1687. ( 10.1136/bmj.g1687) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mellerio H, Jacquin P, Trelles N, Le Roux E, Belanger R, Alberti C, Tubiana-Rufi N, Stheneur C, Guilmin-Crépon S, Devilliers H.Validation of the ‘Good2Go’: the first French-language transition readiness questionnaire. European Journal of Pediatrics 2020. 179 61–71. ( 10.1007/s00431-019-03450-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters A, Laffel L.The American Diabetes Association Transitions Working Group. Diabetes care for emerging adults: recommendations for transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care systems: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association, with representation by the American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the American Osteopathic Association, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Children with Diabetes, the Endocrine Society, the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International, the National Diabetes Education Program, and the Pediatric Endocrine Society (formerly Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society). Diabetes Care 2011. 34 2477–24. ( 10.2337/dc11-1723) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2001. (cited 2020 May 20). (available at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/10027) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rachas A, Lefeuvre D, Meyer L, Faye A, Mahlaoui N, de La Rochebrochard E, Warszawski J, Durieux P.Evaluating continuity during transfer to adult care: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2016. 138 e20160256. ( 10.1542/peds.2016-0256) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gleeson H, Davis J, Jones J, O’Shea E, Clayton PE.The challenge of delivering endocrine care and successful transition to adult services in adolescents with congenital adrenal hyperplasia: experience in a single centre over 18 years. Clinical Endocrinology 2013. 78 23–2. ( 10.1111/cen.12053) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twito O, Shatzman-Steuerman R, Dror N, Nabriski D, Eliakim A.The ‘combined team’ transition clinic model in endocrinology results in high adherence rates and patient satisfaction. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 2019. 32 505–5. ( 10.1515/jpem-2019-0056) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White M, O’Connell MA, Cameron FJ.Transition to adult endocrine services: what is achievable? The diabetes perspective. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2015. 29 497–504. ( 10.1016/j.beem.2015.03.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hobart CB, Phan H.Pediatric-to-adult healthcare transitions: current challenges and recommended practices. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 2019. 76 1544–15. ( 10.1093/ajhp/zxz165) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheehan AM, While AE, Coyne I.The experiences and impact of transition from child to adult healthcare services for young people with Type 1 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetic Medicine 2015. 32 440–4. ( 10.1111/dme.12639) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suris JC, Akre C.Key elements for, and indicators of, a successful transition: an international Delphi study. Journal of Adolescent Health 2015. 56 612–61. ( 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.02.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a