Abstract

Lactylates are an important group of molecules in the food and cosmetic industries. A series of natural halogenated 1-lactylates, chlorosphaerolactylates (1–4), were recently reported from Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249. Here, we identify the cly biosynthetic gene cluster, containing all the necessary functionalities for the biosynthesis of the natural lactylates, based on in silico analyses. Using a combination of stable isotope incorporation experiments and bioinformatic analysis, we propose that dodecanoic acid and pyruvate are the key building blocks in the biosynthesis of 1–4. We additionally report minor analogues of these molecules with varying alkyl chains. This work paves the way to accessing industrially relevant lactylates through pathway engineering.

Humans have been functionalizing different organisms for the desirable effects of their secondary metabolites for thousands of years.1 Of special interest nowadays are natural products (NPs) with pharmacological activities or biotechnological applications, for example, antipathogenic and2,3 anticancer4 activities or biofuels.5 Repurposed natural products are derived from all kingdoms of life and in the last decades cyanobacteria have gained recognition as a plentiful source of NPs.6 In these organisms, the genes for secondary metabolite production are typically organized in biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). Two of the major BGC classes are associated with polyketide synthase (PKS) and nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) enzymes. BGCs that combine elements of these two pathways are also common.7 Beyond the basic assembly logic of PKS/NRPS pathways based on a set of few essential protein domains,8 structural variety is greatly enhanced by additional specialized domains and tailoring enzymes such as methyltransferases,9 glycosyltransferases,10 or halogenases.11 NRPSs can further directly incorporate nonproteinogenic substrates including different amino acids, hydroxy acids, and keto acids,7 overall providing a huge amount of combinatorial possibilities for natural product formation. Such nonproteinogenic substrates are, for example, used by depsipeptide synthetases, specialized NRPSs with the ability to form ester bonds.12

With recent advances in next-generation sequencing technologies, genomic data has become widely accessible. This has led to the accumulation of many so-called “orphan” BGCs, i.e., those without any known secondary metabolites assigned. Still, many known compounds do not have a cognate BGC.13 Knowledge of the underlying biosynthetic machinery of NPs can uncover unprecedented enzymes which often find application as new biocatalysts in synthetic reactions.14 It also enables the transfer of entire BGCs into a suitable host for heterologous expression15 and pathway engineering, leading to increased yields or to the generation of unnatural analogues of economically relevant NPs.16

A class of industrially important compounds are lactylates. They are mainly used as emulsifiers in the food and cosmetic industries.17 Apart from the most common sodium or calcium stearoyl-2-lactylates, several analogues are used in different products.18 Currently, commercial lactylates are produced by esterification of lactic acid and fatty acids and neutralization at elevated temperature.18 Limitations include product impurity18 and dependence on substrate supply chains that feed into other industries.19 Direct microbial production of lactylates could therefore improve the current process.

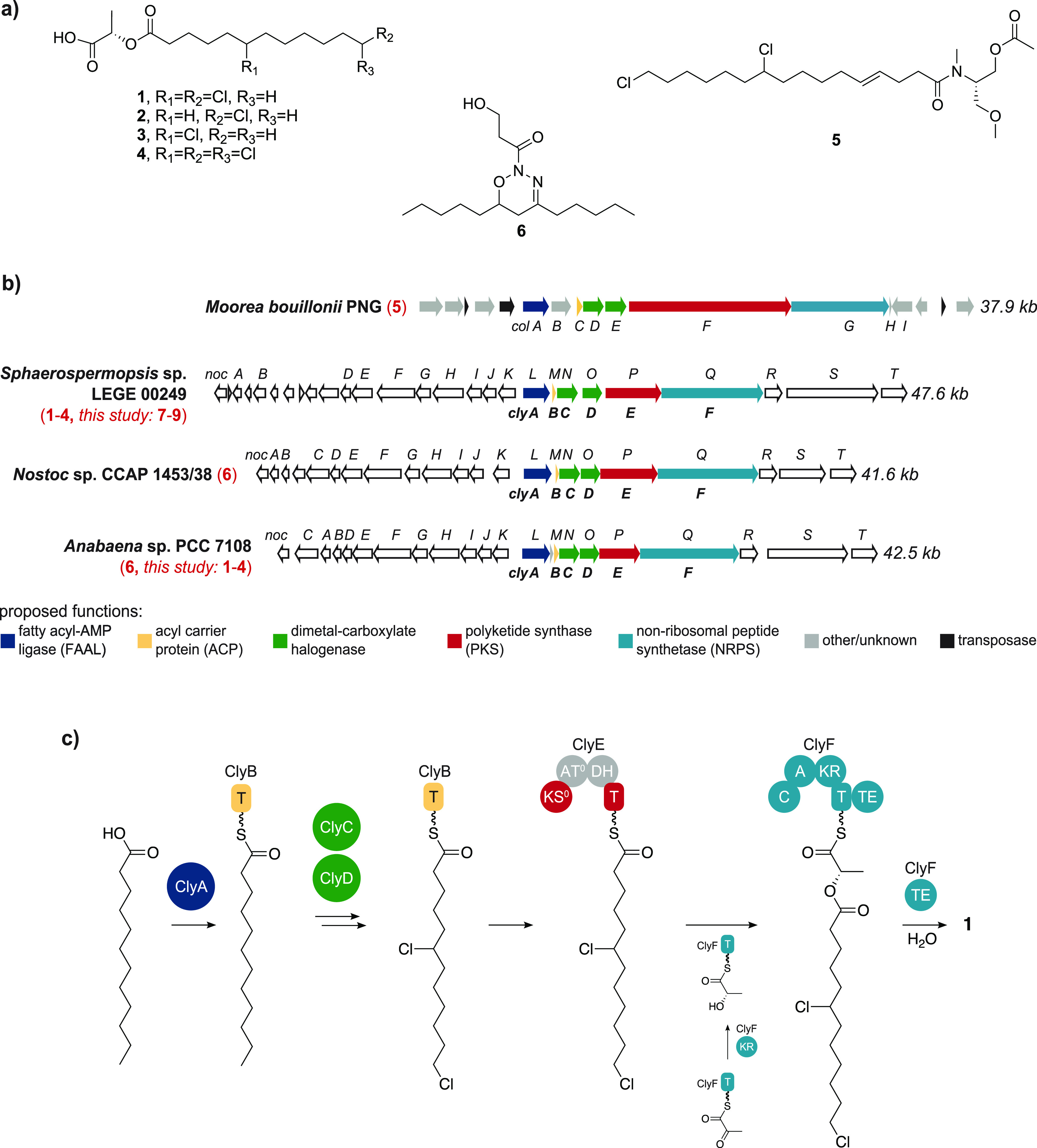

Recently, lactylates of halogenated fatty acids have been isolated from the freshwater cyanobacterium Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249.20 These compounds, termed chlorosphaerolactylates A–D (1–4,Figure 1a), are esters of (poly)chlorinated dodecanoic acid and l-lactic acid. They were discovered in an antibiofilm activity screening and displayed weak antibacterial, antifungal, and antibiofilm properties.20 Their structures bear some resemblance to columbamides (e.g., 5), which, instead of esters, are polychlorinated acyl amides with cannabinomimetic properties.21 Here, we identify a subset of genes, previously assigned to the structurally unrelated nocuolin A (6) BGC (noc),22 and propose their involvement in the biosynthesis of 1–4. We rename this subset of noc genes as the cly BGC and propose the steps involved in chlorosphaerolactylate biosynthesis, notably the recruitment of dodecanoic acid and pyruvate to build the lactylate carbon skeleton, based on a combination of isotopic incorporation experiments and in silico analysis of the cly genes. In addition, we detected analogues of 1–4 with varying acyl chain length. Overall, these biosynthetic insights open up the possibility for pathway engineering and direct microbial production of different widely used lactylates.

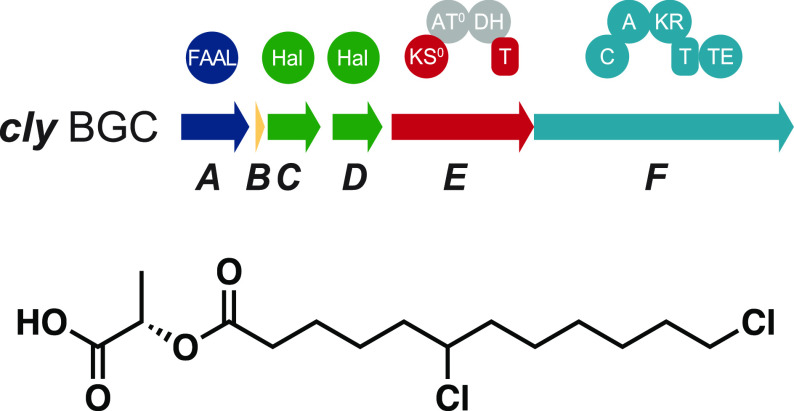

Figure 1.

Structure and biosynthesis of chlorosphaerolactylates. (a) Structures of chlorosphaerolactylates (1–4), of the biosynthetically related columbamide A (5), and of nocuolin A (6), a metabolite that has been putatively associated with the noc cluster. (b) Schematic representations of the proposed BGCs for columbamides (col), chlorosphaerolactylates (cly), and nocuolin A (noc). Relevant compounds reported from each strain are shown next to the taxon. (c) Proposed biosynthesis of the chlorosphaerolactylates (exemplified for compound 1). The ClyE (PKS) step is cryptic in this pathway. Depicted domains are T = thiolation, KS = ketosynthase, AT = acyltransferase, DH = dehydratase, C = condensation domain, A = adenylation domain, KR = ketoreductase, and TE = thioesterase.

Results and Discussion

Identification of a Putative Chlorosphaerolactylate BGC (cly)

We sought to identify the biosynthetic gene cluster responsible for the production of the chlorinated lactylates 1–4. Recognizing the similarity of their halogenated fatty acyl moieties to those of the columbamides (e.g., 5, Figure 1a), we envisioned that similar enzymes might be involved in the biosynthesis of these natural products. After sequencing the genome of Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 (NCBI: PRJNA655889), we searched the resulting nucleotide data for genes encoding halogenases of the CylC-type.23 This recently described dimetal-carboxylate halogenase class has been implicated in the chlorination of fatty acyl-derived moieties of different cyanobacterial natural products, including the columbamides.21,23−25 We found two adjacent homologues of cylC (clyC and clyD) in a ∼225 kb contig. No additional cylC homologues (or genes homologous to nonheme iron halogenases, which may also act on unactivated carbon centers)26,27 were found in the genome data. Annotation of the genomic context of the clyC and clyD halogenases (Table 1) revealed that these were part of a roughly 50 kb region containing multiple biosynthetic genes. This locus has high sequence similarity to the previously reported noc clusters (Figure 1b).22 These loci were associated with the biosynthesis of nocuolin A (6, Figure 1a) by Voráčová and co-workers,22 based on comparative genomics (strains that contained the locus were found to produce 6). Despite the fact that CylC homologues are known to carry out cryptic halogenations and generate nonhalogenated products,23,28 we considered that these two dimetal-carboxylate halogenases found in the LEGE 00249 genome were strong candidate enzymes for carrying out the halogenations in 1–4.

Table 1. Annotation of the cly Gene Cluster Products.

| protein | length [aa] | predicted function | closest homologue and closest Noc homologue | identity/similarity [%] | accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –1 | 397 | transferase | DUF3419 family protein [Moorea sp. SIO2B7] | 84/82 | NES86017.1 |

| ClyA | 626 | FAAL | fatty acyl-AMP ligase [Anabaena sp. PCC 7108] | 82/92 | WP_016949104.1 |

| NocL [Nodularia sp. HBU26] | 79/87 | AQX77690.1 | |||

| ClyB | 92 | ACP | acyl carrier protein [Moorea sp. SIO2B7] | 71/85 | NES81554.1 |

| NocM [Nodularia sp. HBU26] | 76/92 | AQX77692.1 | |||

| ClyC | 471 | halogenase | hypothetical protein [Anabaena sp. PCC 7108] | 87/93 | WP_016949101.1 |

| NocN [Nostoc sp. CCAP 1453/38] | 82/90 | AKL71647.1 | |||

| ClyD | 452 | halogenase | hypothetical protein [Trichormus variabilis] | 84/91 | WP_127052821.1 |

| NocO [Nodularia sp. HBU26] | 84/91 | AQX77693.1 | |||

| ClyE | 1286 | PKS (KS0 [1–496], AT0 [543–769], DH [839–1128], T [1170–1254] | acyltransferase domain-containing protein [Moorea sp. SIO2B7] | 68/81 | NES81557.1 |

| NocP [Nodularia sp. HBU26] | 77/86 | AQX77694.1 | |||

| ClyF | 2325 | NRPS (C [58–517], A [538–1347], KR [1399–1849], T [1934–2009], TE [2042–2313] | NocQ [Nodularia sp. HBU26] | 79/88 | AQX77695.1 |

| +1 | 426 | lipase | NocR [Nostoc sp. CCAP 1453/38] | 82/91 | AKL71651.1 |

Analysis of the cly Gene Cluster

We thoroughly inspected the genes neighboring the halogenases (Figure 1b and Table 1) to consolidate the connection between 1–4 and this locus, which we renamed as the cly BGC. The upstream region of the two halogenases comprises a fatty acyl-AMP ligase (FAAL, clyA) and an acyl carrier protein (ACP, clyB), an arrangement that is also observed in the columbamides (col), microginin (mic), or cylindrocyclophanes (cyl) BGCs.21,23,29 Downstream of the halogenases, a polyketide synthase (clyE) is found before a depsipeptide synthetase NRPS (clyF). Further downstream, a putative lipase and a lectin-like protein are encoded, just upstream of a kinase.

The ClyE PKS is unusual in containing a DH domain while lacking a KR domain. However, the cyanobacterial strain Anabaena sp. PCC7108 which also contains the cly locus and produces 1–4, lacks the DH domain, suggesting evolutionary degradation of the PKS and that this domain is not essential for the proposed biosynthetic pathway (Figure S1). Furthermore, the KS domain of ClyE lacks an active site histidine (detected by antiSMASH30 and confirmed through sequence alignments, Figure S1), and is expected to be a KS0 domain.31−33 In agreement with these observations, ClyE features an AT0 domain, i.e., missing an active site serine residue (Figure S1).33,34 To clarify if ClyE might still have a function in passing on the acyl chain from ClyB to ClyF, we analyzed the specific intermolecular linkers (docking domains) connecting these three enzymes. Alignments of the docking domains of ClyB, ClyE, and ClyF with 382 sequences included in a database of docking domains (DDAP)35 showed highest numbers of identity with docking domains encoded in the jamaicamide BGC, namely, from JamC-JamE and JamN-JamO (Figure S2). In jamaicamide biosynthesis, these docking domains connect a FAAL-associated ACP (JamC) with a PKS (JamE) and a PKS (JamN) with an NRPS (JamO). The resemblance of this architecture to the proposed cly biosynthetic pathway supports a role of the ClyE PKS in transferring the acyl chain from the ACP ClyB to the NRPS ClyF. ClyF has a typical depsipeptide synthetase36,37,12 domain architecture (condensation, adenlyation, ketoreductase, thiolation, C-A-KR-T) and also contains a thioesterase (TE) domain.

We rationalized that the clyA-F (nocL-Q) genes would suffice for the thio-templated biosynthesis and chain-release of 1–4. We propose (Figure 1c) that the biosynthesis of these natural lactylates begins with the activation of dodecanoic acid and transfer to ClyB, catalyzed by the FAAL ClyA. Next, the two halogenases, ClyC and D, would chlorinate the unactivated terminal and/or midchain carbon centers in the fatty acyl-ACP (ClyB) thioester (a similar substrate is halogenated in a midchain position by CylC in cylindrocyclophane biosynthesis).23 The ClyE KS0 domain would then transfer the halogenated acyl moiety to the ClyE ACP (T) domain. KS0 domains have been shown to transfer acyl intermediates between ACPs or between an ACP and a peptidyl carrier protein (PCP).31,32,38 Activation of pyruvate and stereospecific reduction of its α-keto group by the depsipeptide synthetase ClyF A and KR domains, respectively, would prompt the condensation of the lactyl and acyl moieties by the C domain of ClyF, yielding a halogenated dodecanoyl-lactyl-PCP (T) thioester. Finally, thioester hydrolysis mediated by the TE domain in ClyF would yield the final lactylate product (Figure 1c). To obtain further support toward this hypothesis, we turned our attention to the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7108. This strain had been previously reported to contain the noc gene cluster and produce 6.22 It has a clyA-F locus (Figure 1b) with high identity (74%, nucleotide level) to that of Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 and the same structure and PKS/NRPS domain organization, missing only the region corresponding to the DH domain in ClyE (Figure S1). LC-HRESIMS analysis of an organic extract of Anabaena sp. PCC 7108 revealed the presence of 1–4, but these compounds could not be detected in extracts of other cyanobacterial strains whose genomes do not have a cly locus (Figure S3). Overall, these observations support a role for the cly cluster in the biosynthesis of 1–4.

Identification of Dodecanoic Acid as a Building Block for Chlorosphaerolactylate Biosynthesis

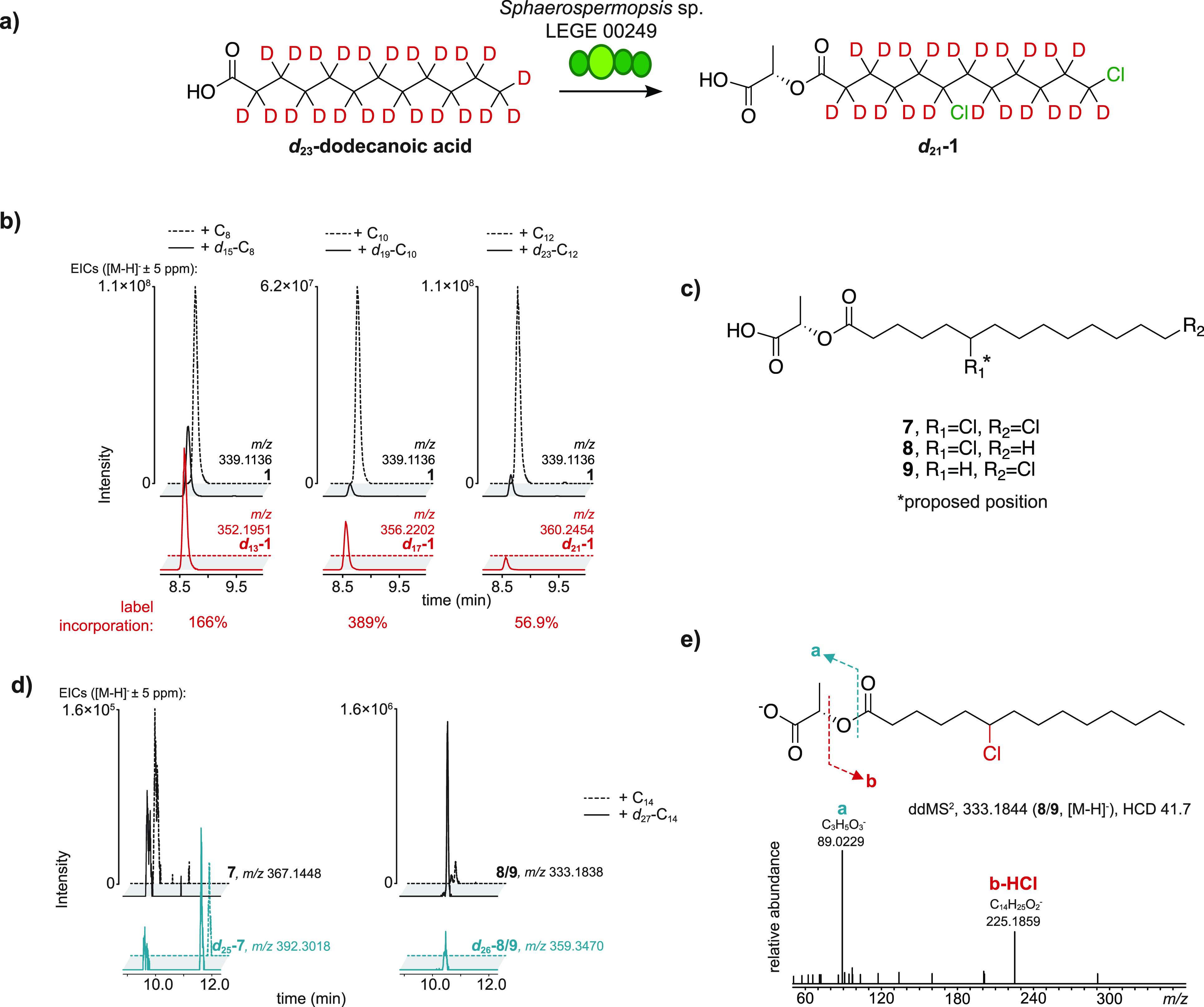

To experimentally test our biosynthetic hypothesis, we carried out isotopic incorporation experiments with putative precursors. We focused first on the fatty acid building block incorporated into 1–4. If the KS0 domain is, as hypothesized, nonelongating, then the entire acyl chain should derive from dodecanoic acid (C12, Figure 1c). We supplemented cultures of Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 with a range of fully deuterated, saturated fatty acids (d15-octanoic = d15-C8, d19-decanoic = d19-C10, d23-C12, and d27-tetradecanoic = d27-C14 acids) and used LC-HRESIMS to detect incorporation of the deuterium labels into 1–4. According to our hypothesis, the shorter fatty acids, C8 and C10, would be elongated to C12 by the FAS complex prior to incorporation into 1–4. As expected, for deuterated C8–C12 fatty acids, we observed incorporation of all the deuterons in the supplemented substrates into the final products, with the exception of those that were removed as a consequence of chlorination (Figure 2a,b, Figure S4). The incorporation efficiency was lower for d23-C12 when compared to d15-C8 and d19-C10, despite the additional elongation step(s) required for the latter. This could be related to the ability of C8 and C10 fatty acids to directly diffuse into the cells,39 while assimilation of exogenous C12 fatty acids should be mostly dependent on acyl-ACP synthetase.40 Surprisingly, we also detected m/z values consistent with tetradecanoic-acid-derived monochlorinated and dichlorinated (but not for trichlorinated) chlorosphaerolactylates (7–9, Figure 2c). In these cases, supplementation with d27-C14 resulted in the expected d25 or d26 incorporation (Figure 2d). LC-HRESIMS/MS analysis of the monochlorinated analogue(s) 8/9 confirmed their relatedness to 1–4 (Figure 2e). However, we could not determine the positioning of the Cl atoms in these compounds. After we consider the structures of columbamides A–E,21,24 the midchain halogenated position relative to the fatty acyl-thioester substrates seems to be conserved, which could be the case for the chlorosphaerolactylates as well. Still, this requires experimental validation, and the structures of 7–9 presented herein are mere proposals. The discovery of these additional analogues prompted us to revisit the LC-HRESIMS data for the organic extracts of Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 in search of other chlorosphaerolactylates with varying acyl chains. As a result, we found traces of metabolites with m/z values consistent with decanoic acid-derived chlorosphaerolactylates (Figure S5). Taken together, these data were in accordance with our proposal of ClyA activating and loading dodecanoic acid to generate 1–4 and suggest that this enzyme also activates decanoic and tetradecanoic acids to generate additional chlorosphaerolactylate diversity. Varying degrees of relaxed substrate specificity have been observed for other FAALs.e.g.41

Figure 2.

Supplementation of Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 with deuterated fatty acids reveals the origin of the acyl group in 1–4 and additional lactylate diversity. (a) Schematic representation of the incorporation of a fully deuterated dodecanoic acid-derived moiety into compound 1. (b) LC-HRESIMS analysis of organic extracts of Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 following supplementation with different fatty acids; extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) of fully deuterium-labeled (red lines) and nonlabeled (black lines) isotopologues of 1 are shown. (c) Proposed structures for tetradecanoic acid-derived chlorosphaerolactylates 7–9, based on (d) LC-HRESIMS detection of dichlorinated (7) and monochlorinated (8/9) chlorosphaerolactylate isotopologues and (e) LC-HRESIMS/MS analysis of 8/9 (the source of the major observed fragments is exemplified for compound 8). ddMS2 = data dependent MS/MS fragmentation, HCD = higher-energy collisional dissociation.

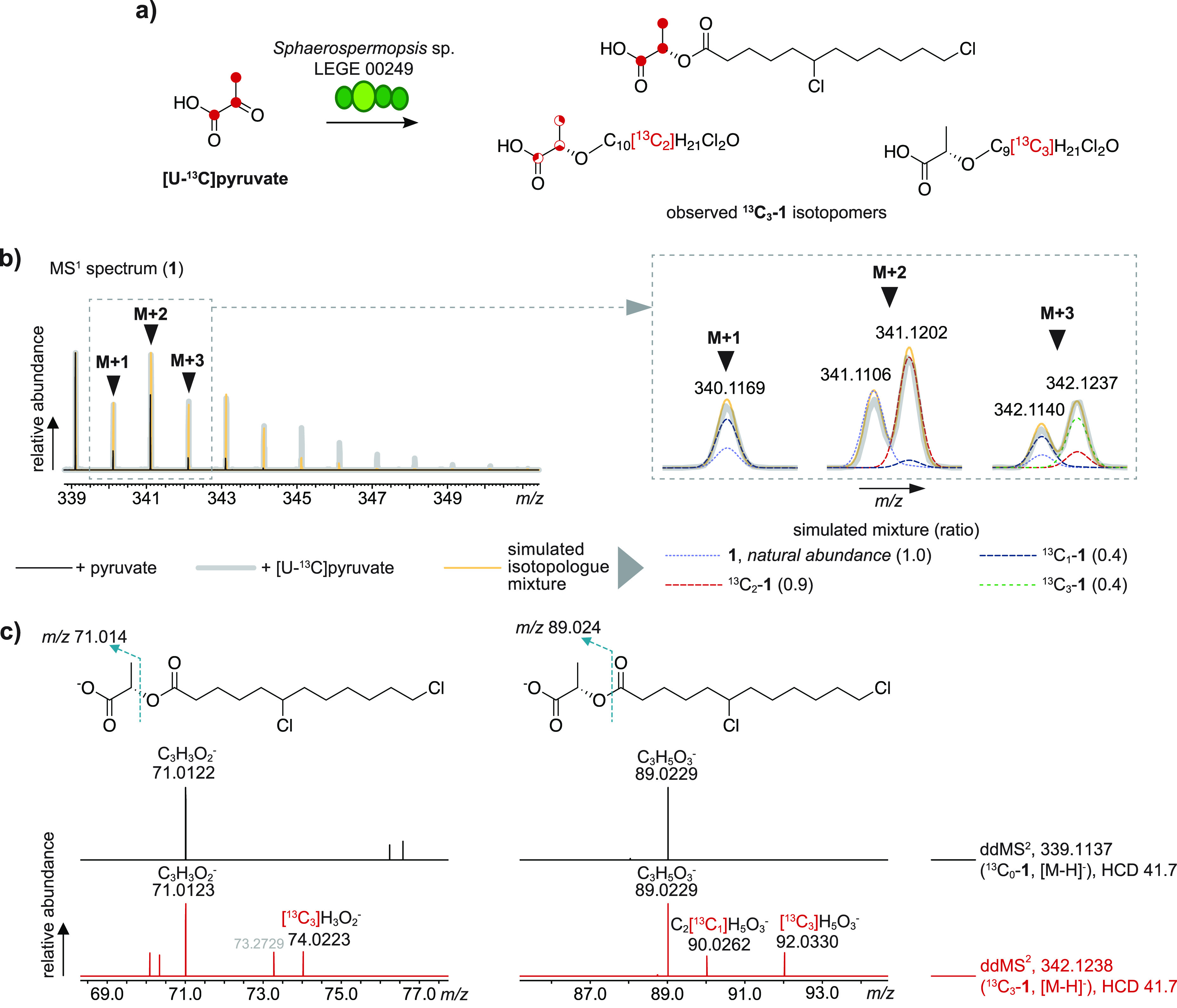

Identification of Pyruvate as a Precursor of the Lactate Moiety in 1–4

We sought to clarify whether pyruvate would be incorporated directly into the lactate portion of 1–4, as per our biosynthetic proposal. We supplemented Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 cultures with [U–13C]pyruvate and analyzed the incorporation of 13C into 1–4 after 7 days using LC-HRESIMS and LC-HRESIMS/MS analyses in the resulting organic extracts. Due to the central metabolic role of pyruvate, in particular its decarboxylative conversion to acetyl-CoA, we expected scrambling of the label to occur and 13C incorporation to be observed potentially in all carbon positions of 1–4, even if pyruvate is not a substrate for ClyF. This was, in fact, observed in [U–13C]pyruvate-supplemented cultures (Figure 3a,b), with a notable enrichment in 13C2-(1–4) and, to a lesser extent, 13C1-(1-4) isotopologues (∼95 and ∼58% of the monoisotopic base peak). Enrichment was clearly observable up to the M + 12 peak, indicating multiple incorporation of 13C atoms. A simulated mixture of isotopologues of 1 that matched the M, M + 1, and M + 2 fine structure indicated that the heavier M + 3 peak only had a minor contribution from 13C1-1 and 13C2-1 isotope patterns and, therefore, was generated mostly from 13C3-1 (Figure 3b). To clarify if an intact [U–13C]pyruvate-derived unit would be incorporated directly into the 13C3-1 isotopomer pool, we resorted to LC-HRESIMS/MS analysis. The MS/MS spectra obtained for both 13C0-1 and 13C3-1 ions ([M – H]−) (Figure 3c) showed a major fragment at m/z 89.023 (calcd for C3H5O3, 89.024), corresponding to the loss of the chlorinated dodecanoyl moiety and confirming that pyruvate-derived carbons were incorporated into the fatty acyl portion of the chlorosphaerolactylates under the supplementation conditions used. In addition, the MS/MS spectrum for the 13C3-1 isotopologue showed a 13C3-lactate-derived fragment at m/z 92.033 (calcd m/z 92.034). A corresponding 13C2 fragment could not be detected, but a 13C1-derived fragment at m/z 90.026 (calcd m/z 90.028) was also present. Likewise, loss of a dichlorododecanoic acid equivalent resulted in a less prominent fragment at m/z 71.012 (calcd m/z 71.014) for 13C0-1 and 13C3-1 isotopologues; in this case, only the corresponding 13C3-derived fragment was observed in the MS/MS spectrum of 13C3-1 (Figure 3c). To examine if we could prevent time-dependent scrambling of the [U–13C]pyruvate label, we performed an additional experiment with only 50 h of supplementation which presented the same overall picture of contribution from 13C3-1 to the M + 3 peak fine structure in full MS analysis and either one or three 13C atoms comprising the lactyl portion in the MS/MS analysis of 13C3-1 isotopomers (Figure S6). Overall, the observed 13C3 incorporation directly from the supplemented [U–13C]pyruvate indicates that the lactate moiety in 1–4 originates from pyruvate. The observed 13C1-incorporation can be explained by fixation of 13CO2 (from decarboxylation of [U–13C]pyruvate) via the Calvin cycle into 13C1-3-phosphoglycerate, eventually leading to 13C1-pyruvate42 (Figure S7).

Figure 3.

Supplementation of Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 with [U–13C]pyruvate. (a) Schematic representation of observed [U-13C]-1 isotopomers following supplementation (full red circles represent incorporation of 13C in that position, partially filled red circles represent positions where 13C incorporation might have occurred). (b) LC-HRESIMS-derived isotope cluster for 1 ([M – H]−), following supplementation of Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 with nonlabeled pyruvate and [U–13C]pyruvate, and for a simulation of a mixture of 13C-enriched isotopologues up to 13C3. Inset shows expanded regions for the M + 1, M + 2, and M + 3 isotopic peaks (black arrowheads). (c) LC-HRESIMS/MS analysis of 13C0-1 and 13C1-1, depicting the two spectral regions where fragments corresponding to the lactate portion of the molecule were observed. ddMS2 = data dependent MS/MS fragmentation, HCD = higher-energy collisional dissociation.

In silico Analysis of the Depsipeptide Synthetase ClyF

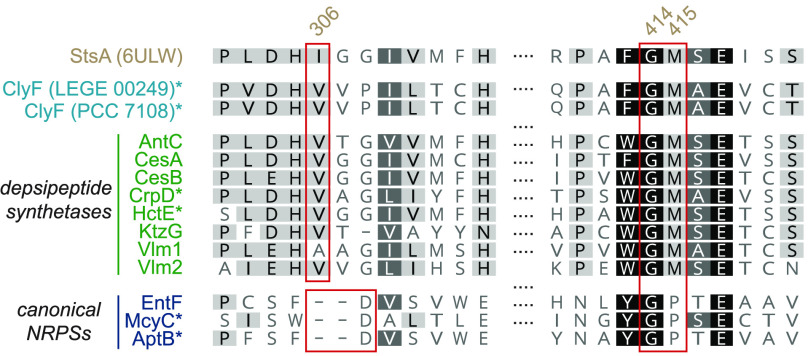

An NRPS-like depsipeptide synthetase, (StsA, PDB ID:6ULW), which utilizes α-ketoisocaproic acid as a substrate, has recently been structurally characterized.12 In that study, Alonzo et al.12 pinpointed two key sequential residues (Gly414 and Met415 in StsA) as conferring selectivity to α-keto acids vs amino acids, by promoting an antiparallel carbonyl–carbonyl interaction between the amide bond connecting the two residues and the α-keto group. Depsipeptide synthetases were also found to contain a hydrophobic residue replacing the Asp featured in canonical NRPSs that is involved in interaction with the amino group.43 Alonzo and co-workers also show that depsipeptide synthetases contain a unique split motif, so-called pseudo Asub domain, composed of ∼30 residues from the N-terminal region and ∼70 residues located between the KR and T domains. This motif appears to be exclusive to keto acid-utilizing NRPSs.12 In light of the results of our pyruvate supplementation experiments, we aimed to understand, by bioinformatic analysis, whether ClyF contained these sequence features associated with depsipeptide synthetases. A BlastP search of the full-length ClyF sequence showed that the cyanobacterial depsipeptide synthetases HctE, HctF, and CrpD were the closest characterized homologues (47.9, 45.8, and 40.4% identity, respectively). HctE and HctF, both involved in hectochlorin biosynthesis,44 contain C-A-KR-T modules; CrpD (part of the cryptophycins BGC)36 contains a C-A-KR-T-TE module. The three enzymes are responsible for incorporating α-keto acids into depsipeptides. Alignment of ClyF with other depsipeptide or canonical NRPS enzymes showed that ClyF contained the Gly-Met motif (Gly1115 and Met1116) and the hydrophobic residue (Val1007) in lieu of the amino group-interacting Asp residue (Figure 4). A homology model of ClyF based on the structure of StsA (PDB ID: 6ULW, Figure S8) showed a similar arrangement of these key residues (Figure S9). A pseudo Asub domain could be modeled from the N-terminus and the region before the thiolation domain, despite a lower quality of the model in these regions (Figure S9). Further substantiating the involvement of ClyF in pyruvate incorporation and modification, the stereoselectivity of the KR domain predicted by antiSMASH analysis (Figure S10) matches the experimentally determined configuration for the lactate stereocenter in 1 (2S), although a single stereospecificity-conferring motif45 is found in depsipeptide synthetase KR domains.12 Overall, the results of the in silico analysis of ClyF were entirely consistent with our biosynthetic proposal, regarding its role in pyruvate loading, reduction, and condensation of the resulting lactyl moiety.

Figure 4.

In silico analysis of ClyF. Sequence alignment of ClyF with StsA (the single depsipeptide synthetase with a currently available crystallographic structure), additional depsipeptide synthetases, and canonical NRPSs. Shown are the regions of previously identified key residues in StsA (Ile306, Gly414, and Met415) that are implicated in the specificity of depsipeptide synthetases toward α-keto acids. Asterisks denote cyanobacterial enzymes.

To conclude, we disclose here a putative biosynthetic pathway for natural 1-lactylates from a photoautotrophic bacterium. Based on in silico analyses, we show that the cly locus contains all the functions necessary for the biosynthesis of the chlorosphaerolactylates 1–4 from dodecanoic acid and pyruvate precursors. We also detected additional congeners of these cyanobacterial metabolites in Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 cells. The cly locus is embedded in the putative nocuolin A (6) (noc) BGC, but 1–4 and 6 are structurally unrelated; the genes surrounding the cly BGC do not seem necessary for the biosynthesis of 1–4. However, Gutiérrez-del-Río et al.20 have reported minor components related to 1–4, with m/z values consistent with 2-lactylates, and therefore, some of the genes neighboring the cly cluster could be associated with these larger metabolites. A report disclosed while this manuscript was under review reported natural products (nocuolactylates) in Nodularia sp. LEGE 06071 that can be regarded as hybrids of lactylates and nocuolin A.46 The discovery of the nocuolactylates suggests that the cly genes and the remainder of the noc locus are involved in the biosynthesis of these hybrids and would explain the findings by Voráčová et al.22 that prompted proposing an association of the noc locus with metabolite 6. However, further genetic and or/biochemical evidence is necessary to confidently assign the function of the noc and cly genes. The chlorosphaerolactylates are assembled under photoautotrophic conditions in a small number of steps, likely by a relatively small BGC with simple and easily accessible intermediates. For all these reasons we consider that their biosynthetic pathway is an attractive target for engineering the microbial production of industrially relevant lactylates.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

LC-HRESIMS and LC-HRESIMS/MS data were acquired with an UltiMate 3000 UHPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific) system composed of an LPG-3400SD pump and WPS-3000SL autosampler and coupled to a Q Exactive Focus hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer controlled by Q Exactive Focus Tune 2.9 and Xcalibur 4.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The capillary voltage of HRESI in negative mode was set to −3.3 kV, the capillary temperature to 320 °C, and the sheath gasflow rate to 5 units. For analysis in switching mode these parameters were −3.3 kV, 300 °C, and 35 units, respectively. LC-MS-grade solvents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific and Carlo Erba. Solvents used for extraction (Thermo Fisher Scientific, VWR) were ACS grade.

Cyanobacterial Strains

Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 was obtained from the LEGE Culture Collection. Anabaena sp. PCC 7108, Anabaena cylindrica PCC 7122, and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 were obtained from the Pasteur Culture Collection. All strains were cultured in Z8 medium47 at 25 °C under a 16:8 h light/dark cycle with a light intensity of 30 μmol photons m–2 s–1. Biomass from stationary-phase batch cultures was harvested by centrifugation (5411 × g, 12 min, 4 °C, Gyrozen 2236R), lyophilized (LyoQuest, Telstar), and stored at −20 °C until extraction.

Genome Sequencing, Mining and BGC annotation

Total genomic DNA was isolated from a fresh pellet of 50 mL of culture of Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 using the commercial PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The genome of Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 was sequenced elsewhere (MicrobesNG) using Illumina technology and 2 × 250 bp paired-end reads. Because the Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 culture was not axenic, the resulting genomic data was treated as a metagenome. Quality-filtered raw reads were assembled into contigs by the sequencing services provider. These were reanalyzed in our lab using the binning tool MaxBin 2.048 and checked manually in order to obtain only cyanobacterial contigs. This yielded a draft genome of Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 (NCBI: PRJNA655889) with an estimated size of 5.3 Mb assembled into 177 contigs. The genome data was mined for homologues of CylC (NCBI: ARU81117.1) and the nonheme iron halogenases SyrB2 (PDB ID: 2FCT_A) and WelO5 (NCBI: AHI58816.1) with the tblastn tool in Geneious 2019.2.1 (Biomatters). The candidate BGC and its translated proteins were annotated based on antiSMASH version 5.1.2,30 NCBI BLAST, and InterProScan. Sequences for Cly proteins can be found in the NCBI under accession numbers MBC5793764-MBC5793765 and MBC5793737-MBC5793740.

Isotopic Incorporation Experiments

Sodium pyruvate (99%, Acros Organics) and sodium [U–13C]pyruvate (99%, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) were diluted in ultrapure water and filtered through 0.2 μm sterile filters. For the 50 h pyruvate isotopic incorporation experiment, sodium pyruvate or sodium [U–13C]pyruvate was dissolved in sterile filtered (0.2 μm) ultrapure H2O. Octanoic acid (98%, Alfa Aesar), decanoic acid (99%, Alfa Aesar), dodecanoic acid (99%, Acros Organics), and tetradecanoic acid (98%, Alfa Aesar) were diluted in DMSO (Fisher BioReagents) at a stock concentration of 500 mM. The corresponding perdeuterated fatty acids (d15-C8, d19-C10, d23-C12, d27-C14, 98%, CDN isotopes) were also diluted in DMSO. Fresh Z8 medium (100 mL for pyruvate (7 days) and decanoic acid incorporation experiments, 50 mL for the remaining precursor conditions) was inoculated with Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 cells to a starting OD750 of 0.04. Cultures were supplemented with the different substrates in two equal pulses (right after and 3 days post inoculation) for a cumulative concentration of 450 μM pyruvate or 100 μM fatty acid. For 50 h pyruvate isotopic incorporation experiments, 100 μM and 200 μM sodium pyruvate or sodium [U–13C]pyruvate were added, respectively, right after inoculation of the cultures. After one-week/50 h incubation on an orbital shaker (Mini-Shaker, VWR) at 190 rpm under otherwise standard culture conditions, the biomass was harvested by centrifugation (5411 × g, 12 min, 4 °C, Gyrozen 2236R) and stored at −20 °C until extraction.

Biomass Extraction

Lyophilized biomass from batch cultures or fresh biomass from isotopic incorporation experiments was fully immersed in CH2Cl2/MeOH (2:1), sonicated for 10 min at 30–35 °C, and filtered through grade 1 filter paper (Whatman), where it was further extracted with CH2Cl2/MeOH (2:1) until no further color could be extracted from the cells. Solvents were evaporated in a rotary evaporator; the resulting extracts were weighed and resuspended in MeOH at 2.0 mg mL–1, filtered (0.2 μm), and used for LC-HRESIMS analyses.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

All LC-HRESIMS separations were performed on an UltraCore 2.5 SuperC18 column (75 × 2.1 mm, ACE) at a flow rate of 0.4 mL min–1. The injection volume was 5 μL, except for LC-HRESIMS/MS of 50 h pyruvate isotopic incorporation experiments for which it was 10 μL. For lactylate detection in the different extracts, the HPLC gradient started with 80% H2O with 0.1% formic acid (eluent A) and 20% MeCN with 0.1% formic acid (eluent B), continued in a linear gradient over 10 min to 100% eluent B, and held for 10 min before returning to the initial conditions. Spectra were recorded in negative mode from the spectrometer running in switching mode (for [U–13C]pyruvate, d19-decanoic acid isotopic incorporation experiments and organic extract of Sphaerospermopsis sp. LEGE 00249 batch culture) or running in negative mode (all other). The scan range was set to m/z 100–900. The resolution in full scan mode was 70 000. For LC-HRESIMS/MS analysis, the scan range was reduced to m/z 50–450, and the resolution was 35 000 with an isolation window of m/z 0.4, offset of m/z 0.2, and a stepped collision energy of 30/40/55 eV.

Mass Spectra Simulations

Spectra for mixtures of natural abundance-and [13C1], [13C2], and [13C3]-enriched chlorosphaerolactylate 1 isotopologues in different proportions were simulated with Xcalibur FreeStyle software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Contributions to the m/z peak fine structure by each individual isotopologue were simulated with Xcalibur Qual Browser (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Bioinformatic Analysis of ClyB, ClyE, and ClyF

Docking domains for sequence alignments were downloaded from the DDAP database,35 containing 382 entries at the time of accession (November 2020). Sequences of C-terminal heads were aligned with ClyB and the 100 C-terminal residues of ClyE; sequences of N-terminal tails were aligned with the 50 N-terminal residues of ClyE and ClyF using MAFFT with a BLOSUM62 matrix in Geneious 2019.2.1 (Biomatters). For all other analyses, including pairwise alignments of the ClyB, ClyE, and ClyF docking domains with the respective best hit from the DDAP database, sequences were aligned with MUSCLE algorithm and Blosum62 matrix in Geneious. For comparison of the active site residues, ClyE was aligned with Bamb_5919 (NCBI accession number ABI91464, KS2-AT2), DEBS III (CAA44449, KS1-AT1), CurL (AEE88278, KS1-AT1), and Slna9 (AEZ53953, KS2-AT2). ClyF was aligned with AntC (AGG37764), CesA (ABK00751), CesB (ABD14712), CrpD (ABM21572), HctE (AAY42397), KtzG (ABV56587), Vlm1 (ABA59547), Vlm2 (ABA59548), EntF (EMX32470), McyC (AAL82384), and AptB (GU174493). Homology models were built with SWISS-MODEL49 from ClyF residues 670–1941 with chain B and chain D of partial StsA (PDB ID: 6ULW) as templates. Models were visualized in Chimera 1.14.50

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding by the European Research Council, through a Starting Grant (Grant Agreement 759840) to P.N.L., and by the European Commission under the H2020 program, NoMorFilm Project (Grant Agreement 634588). The work was additionally supported by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) through projects PTDC/BIA-BQM/29710/2017 to P.N.L., UIDB/04423/2020, and UIDP/04423/2021 and scholarship SFRH/BD/146003/2019 to K.A. Genome sequencing was provided by MicrobesNG (http://www.microbesng.uk) which is supported by the BBSRC (grant number BB/L024209/1).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00950.

Sequence alignments and other bioinformatic analyses, LC-MS, and MS/MS data for additional compounds/cyanobacterial strains and a scheme depicting pyruvate label scrambling (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Newman D. J.; Cragg G. M.; Snader K. M. The Influence of Natural Products upon Drug Discovery. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2000, 17 (3), 215–234. 10.1039/a902202c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick M. H.; McGuire J. M.; Pittenger G. E.; Pittenger R. C.; Stark W. M. Vancomycin, a New Antibiotic. I. Chemical and Biologic Properties. Antibiotics annual 1955, 3, 606–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klayman D. L. Qinghaosu (Artemisinin): An Antimalarial Drug from China. Science 1985, 228 (4703), 1049–1055. 10.1126/science.3887571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luesch H.; Moore R. E.; Paul V. J.; Mooberry S. L.; Corbett T. H. Isolation of Dolastatin 10 from the Marine Cyanobacterium Symploca Species VP642 and Total Stereochemistry and Biological Evaluation of Its Analogue Symplostatin 1. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64 (7), 907–910. 10.1021/np010049y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang X.; Kilian O.; Monroe E.; Ito M.; Tran-Gymfi M. B.; Liu F.; Davis R. W.; Mirsiaghi M.; Sundstrom E.; Pray T.; Skerker J. M.; George A.; Gladden J. M. Monoterpene Production by the Carotenogenic Yeast Rhodosporidium Toruloides. Microb. Cell Fact. 2019, 18 (54), 1. 10.1186/s12934-019-1099-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burja A. M.; Banaigs B.; Abou-Mansour E.; Grant Burgess J.; Wright P. C. Marine Cyanobacteria - A Prolific Source of Natural Products. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 9347–9377. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)00931-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C. T.; O’Brien R. V.; Khosla C. Nonproteinogenic Amino Acid Building Blocks for Nonribosomal Peptide and Hybrid Polyketide Scaffolds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52 (28), 7098–7124. 10.1002/anie.201208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach M. A.; Walsh C. T. Assembly-Line Enzymology for Polyketide and Nonribosomal Peptide Antibiotics: Logic, Machinery, and Mechanisms. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 3468. 10.1021/cr0503097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skiba M. A.; Sikkema A. P.; Moss N. A.; Tran C. L.; Sturgis R. M.; Gerwick L.; Gerwick W. H.; Sherman D. H.; Smith J. L. A Mononuclear Iron-Dependent Methyltransferase Catalyzes Initial Steps in Assembly of the Apratoxin A Polyketide Starter Unit. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12 (12), 3039–3048. 10.1021/acschembio.7b00746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H. P.; Yokoyama K. Characterization of Acyl Carrier Protein-Dependent Glycosyltransferase in Mitomycin C Biosynthesis. Biochemistry 2019, 58 (25), 2804. 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S.; Pang A. H.; Thamban Chandrika N.; Garneau-Tsodikova S.; Tsodikov O. V. Unusual Substrate and Halide Versatility of Phenolic Halogenase PltM. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1255), 1. 10.1038/s41467-019-09215-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo D. A.; Chiche-Lapierre C.; Tarry M. J.; Wang J.; Schmeing T. M. Structural Basis of Keto Acid Utilization in Nonribosomal Depsipeptide Synthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16 (5), 493–496. 10.1038/s41589-020-0481-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P. R. Natural Products and the Gene Cluster Revolution. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24 (12), 968–977. 10.1016/j.tim.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltschi B.; Cernava T.; Dennig A.; Galindo Casas M.; Geier M.; Gruber S.; Haberbauer M.; Heidinger P.; Herrero Acero E.; Kratzer R.; Luley-Goedl C.; Müller C. A.; Pitzer J.; Ribitsch D.; Sauer M.; Schmölzer K.; Schnitzhofer W.; Sensen C. W.; Soh J.; Steiner K.; Winkler C. K.; Winkler M.; Wriessnegger T. Enzymes Revolutionize the Bioproduction of Value-Added Compounds: From Enzyme Discovery to Special Applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 40, 107520. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Li S.; Thodey K.; Trenchard I.; Cravens A.; Smolke C. D. Complete Biosynthesis of Noscapine and Halogenated Alkaloids in Yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115 (17), E3922–E3931. 10.1073/pnas.1721469115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltz R. H. Combinatorial Biosynthesis of Cyclic Lipopeptide Antibiotics: A Model for Synthetic Biology to Accelerate the Evolution of Secondary Metabolite Biosynthetic Pathways. ACS Synth. Biol. 2014, 3, 748–758. 10.1021/sb3000673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. C.; Marangoni A. G. Advances in the Application of Food Emulsifier α-Gel Phases: Saturated Monoglycerides, Polyglycerol Fatty Acid Esters, and Their Derivatives. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 483, 394–403. 10.1016/j.jcis.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutte T.; Skogerson L. Stearoyl-2-Lactylates and Oleoyl Lactylates. Emulsifiers in Food Technology: Second ed. 2014, 9780470670, 251–270. 10.1002/9781118921265.ch11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alves de Oliveira R.; Komesu A.; Vaz Rossell C. E.; Maciel Filho R. Challenges and Opportunities in Lactic Acid Bioprocess Design—From Economic to Production Aspects. Biochem. Eng. J. 2018, 133, 219–239. 10.1016/j.bej.2018.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-del-Río I.; Brugerolle de Fraissinette N.; Castelo-Branco R.; Oliveira F.; Morais J.; Redondo-Blanco S.; Villar C. J.; Iglesias M. J.; Soengas R.; Cepas V.; Cubillos Y. L.; Sampietro G.; Rodolfi L.; Lombó F.; González S. M. S.; López Ortiz F.; Vasconcelos V.; Reis M. A. Chlorosphaerolactylates A–D: Natural Lactylates of Chlorinated Fatty Acids Isolated from the Cyanobacterium Sphaerospermopsis Sp. LEGE 00249. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 1885. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleigrewe K.; Almaliti J.; Tian I. Y.; Kinnel R. B.; Korobeynikov A.; Monroe E. A.; Duggan B. M.; Di Marzo V.; Sherman D. H.; Dorrestein P. C.; Gerwick L.; Gerwick W. H. Combining Mass Spectrometric Metabolic Profiling with Genomic Analysis: A Powerful Approach for Discovering Natural Products from Cyanobacteria. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78 (7), 1671–1682. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voráčová K.; Hájek J.; Mareš J.; Urajová P.; Kuzma M.; Cheel J.; Villunger A.; Kapuscik A.; Bally M.; Novák P.; Kabeláč M.; Krumschnabel G.; Lukeš M.; Voloshko L.; Kopecký J.; Hrouzek P. The Cyanobacterial Metabolite Nocuolin a Is a Natural Oxadiazine That Triggers Apoptosis in Human Cancer Cells. PLoS One 2017, 12 (3), e0172850. 10.1371/journal.pone.0172850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H.; Schultz E. E.; Balskus E. P. A New Strategy for Aromatic Ring Alkylation in Cylindrocyclophane Biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13 (8), 916–921. 10.1038/nchembio.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez J. A. V.; Petitbois J. G.; Vairappan C. S.; Umezawa T.; Matsuda F.; Okino T. Columbamides D and E: Chlorinated Fatty Acid Amides from the Marine Cyanobacterium Moorea Bouillonii Collected in Malaysia. Org. Lett. 2017, 19 (16), 4231–4234. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leão P. N.; Nakamura H.; Costa M.; Pereira A. R.; Martins R.; Vasconcelos V.; Gerwick W. H.; Balskus E. P. Biosynthesis-Assisted Structural Elucidation of the Bartolosides, Chlorinated Aromatic Glycolipids from Cyanobacteria. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (38), 11063–11067. 10.1002/anie.201503186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasiak L. C.; Vaillancourt F. H.; Walsh C. T.; Drennan C. L. Crystal Structure of the Non-Haem Iron Halogenase SyrB2 in Syringomycin Biosynthesis. Nature 2006, 440 (7082), 368–371. 10.1038/nature04544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillwig M. L.; Fuhrman H. A.; Ittiamornkul K.; Sevco T. J.; Kwak D. H.; Liu X. Identification and Characterization of a Welwitindolinone Alkaloid Biosynthetic Gene Cluster in the Stigonematalean Cyanobacterium Hapalosiphon Welwitschii. ChemBioChem 2014, 15 (5), 665–669. 10.1002/cbic.201300794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis J. P. A.; Figueiredo S. A. C.; Sousa M. L.; Leão P. N. BrtB Is an O-Alkylating Enzyme That Generates Fatty Acid-Bartoloside Esters. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 1458. 10.1038/s41467-020-15302-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H.; Hamer H. A.; Sirasani G.; Balskus E. P. Cylindrocyclophane Biosynthesis Involves Functionalization of an Unactivated Carbon Center. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (45), 18518–18521. 10.1021/ja308318p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blin K.; Shaw S.; Steinke K.; Villebro R.; Ziemert N.; Lee S. Y.; Medema M. H.; Weber T. AntiSMASH 5.0: Updates to the Secondary Metabolite Genome Mining Pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47 (W1), W81–W87. 10.1093/nar/gkz310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Tang G. L.; Pan G.; Chang C. Y.; Shen B. Characterization of the Ketosynthase and Acyl Carrier Protein Domains at the LnmI Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetase-Polyketide Synthase Interface for Leinamycin Biosynthesis. Org. Lett. 2016, 18 (17), 4288–4291. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masschelein J.; Sydor P. K.; Hobson C.; Howe R.; Jones C.; Roberts D. M.; Ling Yap Z.; Parkhill J.; Mahenthiralingam E.; Challis G. L. A Dual Transacylation Mechanism for Polyketide Synthase Chain Release in Enacyloxin Antibiotic Biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11 (10), 906–912. 10.1038/s41557-019-0309-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keatinge-Clay A. T. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 5334. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C.; Wang H.; Kang Q.; Liu J.; Bai L. Cloning and Characterization of the Polyether Salinomycin Biosynthesis Gene Cluster of Streptomyces Albus XM211. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78 (4), 994–1003. 10.1128/AEM.06701-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T.; Tripathi A.; Yu F.; Sherman D. H.; Rao A. DDAP: Docking Domain Affinity and Biosynthetic Pathway Prediction Tool for Type I Polyketide Synthases. Bioinformatics 2019, 36 (3), 942–944. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magarvey N. A.; Beck Z. Q.; Golakoti T.; Ding Y.; Huber U.; Hemscheidt T. K.; Abelson D.; Moore R. E.; Sherman D. H. Biosynthetic Characterization and Chemoenzymatic Assembly of the Cryptophycins. Potent Anticancer Agents from Nostoc Cyanobionts. ACS Chem. Biol. 2006, 1 (12), 766–779. 10.1021/cb6004307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehling-Schulz M.; Vukov N.; Schulz A.; Shaheen R.; Andersson M.; Märtlbauer E.; Scherer S. Identification and Partial Characterization of the Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetase Gene Responsible for Cereulide Production in Emetic Bacillus Cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71 (1), 105–113. 10.1128/AEM.71.1.105-113.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich E. J. N.; Piel J. Biosynthesis of Polyketides by Trans-AT Polyketide Synthases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33 (2), 231–316. 10.1039/C5NP00125K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloy S. R.; Ginsburgh C. L.; Simons R. W.; Nunn W. D. Transport of Long and Medium Chain Fatty Acids by Escherichia Coli K12. J. Biol. Chem. 1981, 256 (8), 3735–3742. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)69516-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarzyk D.; Fulda M. Fatty Acid Activation in Cyanobacteria Mediated by Acyl-Acyl Carrier Protein Synthetase Enables Fatty Acid Recycling. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152 (3), 1598–1610. 10.1104/pp.109.148007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmerling F.; Lebe K. E.; Wunderlich J.; Hahn F. An Unusual Fatty Acyl:Adenylate Ligase (FAAL)–Acyl Carrier Protein (ACP) Didomain in Ambruticin Biosynthesis. ChemBioChem 2018, 19 (10), 1006–1011. 10.1002/cbic.201800084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz D.; Orf I.; Kopka J.; Hagemann M. Recent Applications of Metabolomics Toward Cyanobacteria. Metabolites 2013, 3 (1), 72–100. 10.3390/metabo3010072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori D. G.; Hrvatin S.; Neumann C. S.; Strieker M.; Marahiel M. A.; Walsh C. T. Cloning and Characterization of the Biosynthetic Gene Cluster for Kutznerides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104 (42), 16498–16503. 10.1073/pnas.0708242104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy A. V.; Sorrels C. M.; Gerwick W. H. Cloning and Biochemical Characterization of the Hectochlorin Biosynthetic Gene Cluster from the Marine Cyanobacterium Lyngbya Majuscula. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70 (12), 1977–1986. 10.1021/np0704250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keatinge-Clay A. T.; Stroud R. M. The Structure of a Ketoreductase Determines the Organization of the β-Carbon Processing Enzymes of Modular Polyketide Synthases. Structure 2006, 14 (4), 737–748. 10.1016/j.str.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo S. A. C.; Preto M.; Moreira G.; Martins T. P.; Abt K.; Melo A.; Vasconcelos V. M.; Leao P. Discovery of Cyanobacterial Natural Products Containing Fatty Acid Residues 2020, 1. 10.26434/chemrxiv.13100564.v2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippka R. Isolation and Purification of Cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1988, 167 (C), 3–27. 10.1016/0076-6879(88)67004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. W.; Simmons B. A.; Singer S. W. MaxBin 2.0: An Automated Binning Algorithm to Recover Genomes from Multiple Metagenomic Datasets. Bioinformatics 2016, 32 (4), 605–607. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A.; Bertoni M.; Bienert S.; Studer G.; Tauriello G.; Gumienny R.; Heer F. T.; De Beer T. A. P.; Rempfer C.; Bordoli L.; Lepore R.; Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: Homology Modelling of Protein Structures and Complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46 (W1), W296–W303. 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E. F.; Goddard T. D.; Huang C. C.; Couch G. S.; Greenblatt D. M.; Meng E. C.; Ferrin T. E. UCSF Chimera - A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25 (13), 1605–1612. 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.