Abstract

The anticancer agents of the anthracycline family are commonly associated with the potential to cause severe toxicity to the heart. To solve the question of why particular a patient is predisposed to anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity (AIC), researchers have conducted numerous pharmacogenomic studies and identified more than 60 loci associated with AIC. To date, none of these identified loci have been developed into US FDA-approved biomarkers for use in routine clinical practice. With advances in the application of human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, sequencing technologies and genomic editing techniques, variants associated with AIC can now be validated in a human model. Here, we provide a comprehensive overview of known genetic variants associated with AIC from the perspective of how human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes can be used to help better explain the genomic predilection to AIC.

Keywords: : cardiomyocyte, cardiotoxicity, genomic editing, human-induced pluripotent stem cells, pharmacogenomics

Adverse drug events (ADEs) are one of the leading causes of death worldwide. According to the US FDA adverse drug events reporting system, more than 2 million serious (including death) ADEs were reported in 2019 in the USA alone (fis.fda.gov). Reports of cardiotoxic ADEs have increased by almost 16-fold in the period between 2005 and 2019 (fis.fda.gov). The anticancer agent doxorubicin (DOX) is the drug most commonly associated with severe cardiovascular ADEs. DOX was originally isolated from a mutated strain of Streptomyces peucetius bacterium and is a member of the anthracycline family that includes other chemotherapy agents such as daunorubicin, epirubicin and idarubicin. DOX has been a cornerstone of chemotherapeutic treatment regimens for multiple types of cancers for more than 50 years and has played a major role in the increase in the 5-year survival rate in childhood cancers to more than 80% [1]. Despite this, the therapeutic utility of DOX is limited because of its cardiotoxicity, defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) reduction of greater than 10% to less than 53%. Even recent clinical trials have suggested that this cardiotoxicity occurs in 14.5% of breast cancer patients receiving the most common cumulative dose of 240 mg/m2 [2]. The cardiotoxicity of DOX is also well understood to be dose dependent, with 65 and 85% of cancer patients experiencing a decline in LVEF when treated with DOX dose of 550 and 700 mg/m2, respectively [3], and therefore the maximum lifetime cumulative dose is limited to 400–550 mg/m2, potentially restricting the chemotherapeutic efficacy [4,5]. With more sophisticated methods of measuring the impact of DOX on the heart such as MRI, it is thought that 65% of pediatric cancer survivors develop a measurable impairment in cardiac function even when treated with low doses of DOX [6]. Hence, it is clearly of great importance to unravel the genetic causes of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity (AIC) to be able to identify AIC high-risk patients before initiating the treatment and to help develop cardioprotective agents based upon genetically identified druggable targets. In this work, we provide a comprehensive overview of known genetic variants associated with AIC. We also review how human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) could help better explain the genetic predispositions to AIC and facilitate the discovery of novel cardioprotectants.

Review of genomic loci associated with AIC

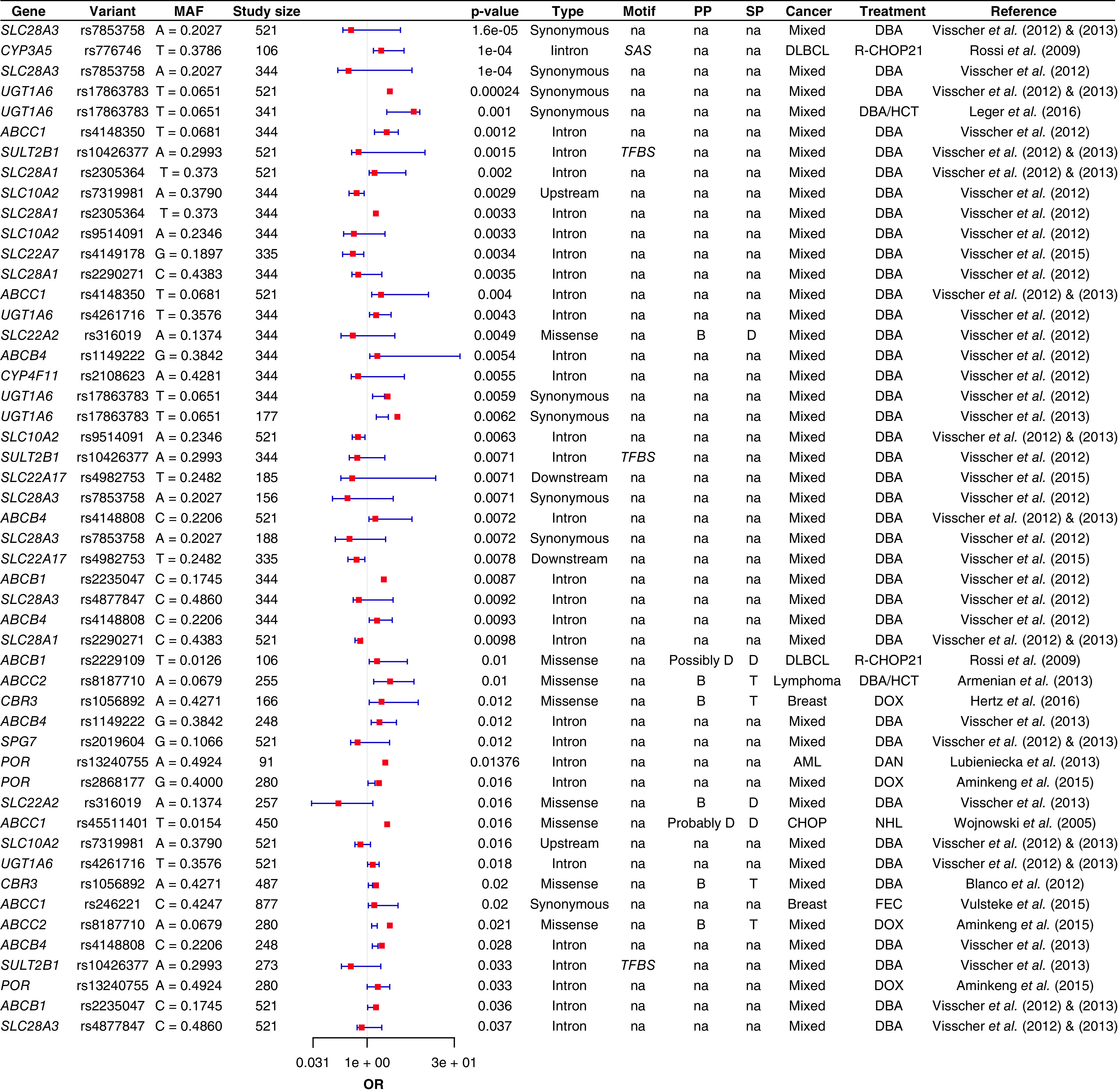

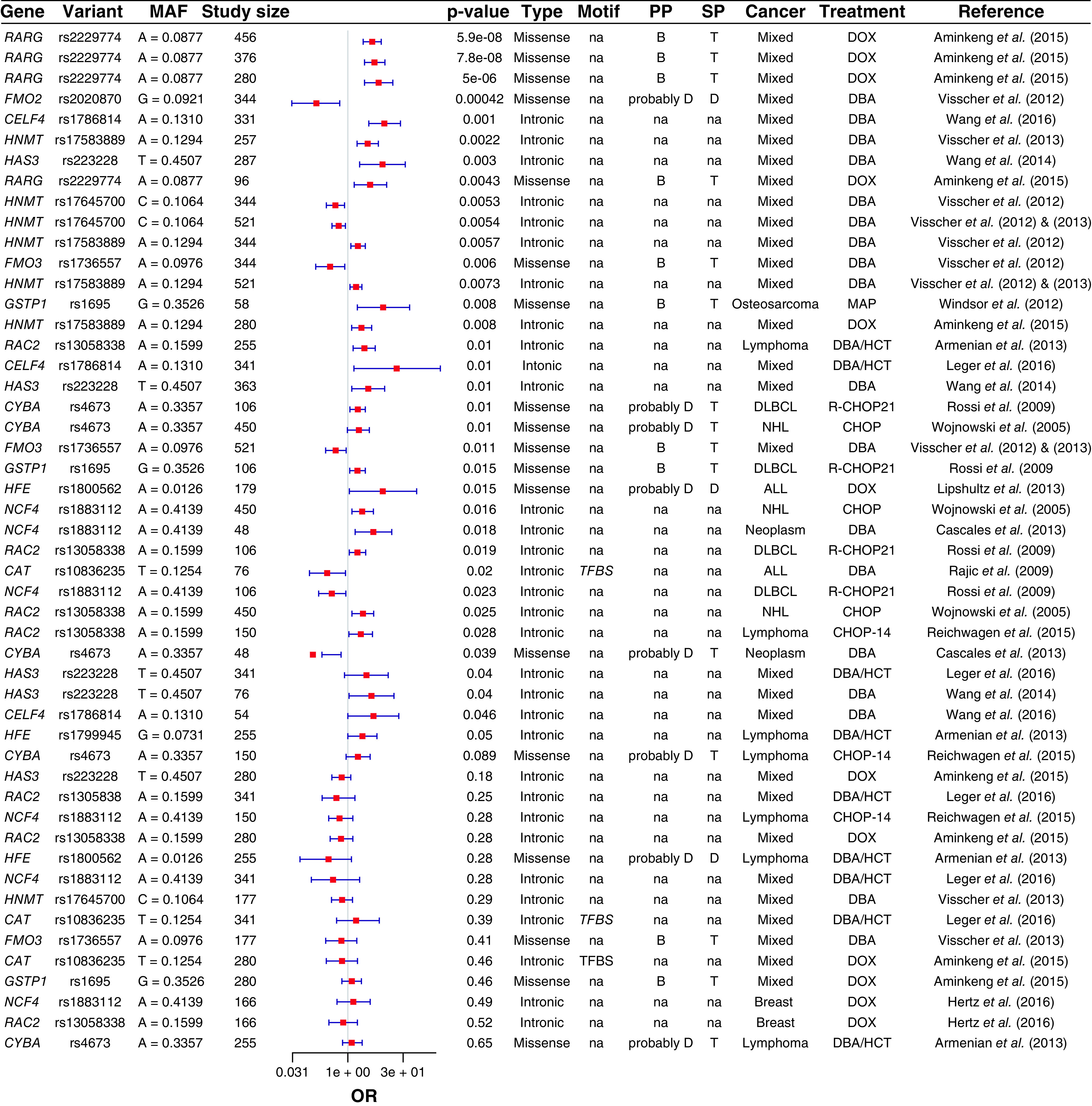

Numerous pharmacogenomic studies have been completed to identify genetic variants associated with AIC, and collectively they have identified about 60 AIC-associated loci. Importantly, with only a very few exceptions, AIC-associated loci identified in one study failed to be replicated in other fully independent cohorts, a fact that raises several important concerns regarding the methodologies used and the complexity of the pharmacogenomics of AIC. The majority of these studies adopted a candidate gene approach, while only a handful of studies adopted a genome-wide association-based approach. These candidate gene approaches are biased toward studying drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters and therefore, the majority of the identified AIC-associated loci are located in these genes, hypothesized to alter their expression and/or activity, and therefore influencing DOX pharmacokinetics (Figure 1) or pharmacodynamics (Figure 2).

Figure 1. . Genetic susceptibility of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity pharmacokinetic pathway.

Forest plot showing the top significant AIC-associated loci located in anthracyclines pharmacokinetic pathway.

AIC: Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity; AML: Acute myeloid leukemia; B: Benign; CHOP: Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone; D: Damaging; DAN: Daunorubicin; DBA: Doxorubicin-based anthracyclines; DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; DOX: Doxorubicin; FES: 5-Fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide; HCT: Hematopoietic cell transplantation; MAF: Minor allele frequency; OR: Odds ratio; PP: Polyphen prediction; SP: Sift prediction; T: Tolerable; TFBS: Transcription factor-binding site; SAS: Splice acceptor site.

Figure 2. . Genetic susceptibility of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity pharmacodynamic pathway.

Forest plot showing the top significant AIC-associated loci located in anthracyclines pharmacodynamic pathway.

AIC: Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity; ALL: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML: Acute myeloid leukemia; B: Benign; CHOP: Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone; D: Damaging; DAN: Daunorubicin; DBA: Doxorubicin-based anthracyclines; DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; DOX: Doxorubicin; FES: 5-Fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide; HCT: Hematopoietic cell transplantation; MAF: Minor allele frequency; MAP: Methotrexate, doxorubicin and cisplatin; NHL: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma; OR: Odds ratio; PP: Polyphen prediction; SP: Sift prediction; T: Tolerable; TFBS: Transcription factor-binding site; SAS: Splice acceptor site.

Genetic variants affecting the pharmacokinetics pathway of DOX

DOX is commonly administered as an intravenous infusion, with the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) peaking immediately after administration reported variously as 1.59 [7], 9.9 [8] or 13.12 μM [9] with a standard single dose of 60 mg/m2. Within 15–30 min after administration, 50% of the dose is excreted unchanged in bile and the remainder is taken up by cells and metabolized intracellularly.

DOX cellular uptake occurs via several solute carrier (SLC) transporters. Transporter-related genes represent approximately 10% (∼2000) of the human genome, which aligns with their crucial biological role in cell homeostasis. SLC transporters family includes more than 450 members distributed across more than 65 subfamilies (http://slc.bioparadigms.org/) and constitutes the second largest family of transmembrane proteins in the human genome [10]. The normal physiological role of SLC transporters is the uptake of ions (Na+, Ca2+ and Fe2+), nucleosides, small molecules (bile acids, glucose and galactose) and amino acids, across cellular membranes. Importantly, many drugs have been increasingly identified as substrates for SLC transporters, thus SLC transports have a substantial role in both drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Several SLC transporters have been linked to DOX uptake and clinical outcomes.

SLC transporter variants have been identified as associated with AIC. A coding synonymous SNP rs7853758 (L461L) in SLC28A3 that encodes the solute carrier transporter family 28 member 3, an Na+ coupled nucleoside transporter, represents the most robustly associated loci with lower risk (i.e., protective) of developing AIC in three independent cohorts (Figure 1) [11,12]. Although well-replicated, this variant is most likely is not the causal SNP due to it being synonymous, and hence further investigation at this locus is required to pinpoint the causal cardioprotective variant in SLC28A3.

Another SLC gene associated with AIC is SLC22A16. The variant rs714368 (A >G, H49R) in this gene was shown to increase DOX influx, with breast cancer patients harboring the GG genotype demonstrating higher DOX and doxorubicinol (DOX-ol) intracellular concentrations when compared with the reference allele carriers [13]. Another SNP rs12210538 (M409T) in the same influx transporter is associated with a higher incidence of DOX dose delay (i.e., patient chemotherapy was paused) that indicates severe doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity (DIC) in the carriers of this variant [14]. On the contrary, synonymous variant rs6907567 and nonsynonymous variant rs723685 (V252A) in SLC22A16 are associated with a significantly lower incidence of DOX dose delay indicating a lower incidence of DOX-induced toxicity (DIC) [14].

SNPs in other SLC transporters, such as rs9514091 in the sodium bile salt cotransporter SLC10A2, have been associated with severe cardiotoxicity [11] in DOX-treated cancer patients. Moreover, intronic SNPs rs4149178 in SLC22A7 and rs4982753 located downstream of SLC22A17 are correlated with severe AIC in pediatric cancer patients [15]. These findings suggest that DOX is transported into the cells via multiple SLC transporters especially the 28 and 22 families and thus functional validation of the role of these transporters in hiPSC-CMs is essential for identifying DIC-related biomarkers and cardioprotectants.

Once inside the cell, DOX is reduced to the secondary alcohol DOX-ol in a reaction that is catalyzed by CBR1, CBR3, AKR1A and AKR1C3 [16,17]. The accumulation of these alcohol toxic metabolites in cardiomyocytes depresses cardiac contractile function and increases cardiac muscle stiffness through the inhibition of the Ca2+ loading of the sarcoplasmic reticulum [18]. Several studies have identified genetic polymorphisms located in DOX metabolizing enzymes that alter the intracellular concentration of DOX metabolites. The genetic variant, rs9024 located in the 3′-untranslated region of CBR1 (1096G >A), is associated with altered CBR1 protein expression and metabolic activity measured by altered levels of DOX-ol in human livers [19]. Lymphoma patients harboring this variant had experienced severe thrombocytopenia and diarrhea after treatment with a DOX-based combinatorial treatment regimen [20]. Similarly, a nonsynonymous SNP rs1056892 (V244M) located in a region critical for the interaction of CBR3 with the NADP(H) cofactor is associated with the higher metabolic activity of CBR3 [21]. SNP rs1056892 in CBR3 is another variant that has been consistently associated with a higher incidence of cardiotoxicity after DOX treatment (Figure 1) [22,23].

Following the initial reduction of DOX, DOX-ol and the remaining DOX undergo reductase and hydrolase glycosidation reactions that are catalyzed by mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenases present in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria including NDUFS2, NDUFS3 and NDUFS7, as well as cytosolic enzymes such as NQO1, XDH, POR , NOS1, NOS2 and NOS3. These reactions result in the generation of DOX deoxyaglycone or doxorubicinone from DOX and DOX-ol hydroxyaglycone or doxorubicinolone (DOX-olone) from DOX-ol, while also forming semiquionones as intermediate metabolites. This step also generates superoxide and hydrogen peroxide-free radicals that result in oxidative stress-induced cardiotoxicity. Zhang et al. showed that SNP rs2868177 alters POR-mediated warfarin metabolism suggesting an alteration in POR metabolic activity [24]. This polymorphism, along with rs13240755 in POR are correlated with anthracycline accumulative dose and with a significant drop in the LVEF in acute myeloid leukemia patient (Figure 1) [25]. In addition, patients harboring SNP rs1799983 in NOS3 are protected from AIC [26].

UGT1A6 that encodes UDP-gluronosyltransferase family 1 member A6 is responsible for the detoxification of several xenobiotics including anthracyclines. UGT1A6 adds a glucuronic acid moiety to drug metabolites rendering them hydrophilic and thus eliminated easily from the body. Several mutations in UGT1A6 have been found to alter its metabolic activity as well as UGT1A6-dependent drug clearance [27]. Interestingly, two genetic variants, rs17863783 and rs4261716 in UGT1A6 are associated with a higher incidence of DIC (Figure 1) [11,12]. Of note, UGT1A6 does not appear to be expressed in human cardiomyocytes and thus the functional influence of these variants is likely via modified metabolism in the liver.

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are responsible for the efflux (i.e., removal from the cell) of many substrates, and genetic variants in the ABC family have been shown to alter the pharmacokinetics of several drugs [28,29]. Interestingly, it has been shown that DOX can be transported by several ABC transporters including, ABCB1, ABCC1, ABCC2, ABCC5 and ABCG2. Genetic polymorphism rs1128503 decreases the ABCB1-mediated transport of DOX [30]. Multiple other ABCB1 variants have been found associated with DOX clinical outcomes including rs2229109 and rs2032582 that are associated with DIC [31,32], and rs1045642 that has a cardioprotective effect against DIC [23]. Expression of ABCC1 confers resistant to DOX and ABCC1 inhibitors mifepristone and rosiglitazone resensitize lung carcinoma cell lines to DOX [33]. Wojnowski et al. demonstrated that ABCC1 nonsynonymous SNPs rs8187694 (V1188Q) and rs8187710 (C1515W) are associated with acute DIC (Figure 1) [34]. Folmer et al. showed that ABCC2 alters chemosensitization of DOX and that ABCC2 downregulation results in a 16-fold reduction in DOX half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) in HepG2 cells [35]. Likewise, breast cancer lines overexpressing ABCG2 are resistant to DOX [36]. SNP rs1533682 in ABCC5 is significantly associated with higher DOX clearance in Asian breast cancer patients [37]. Conversely, variant rs7627754 located in the 3′-UTR of ABCC5 is associated with a 12% reduction in ejection (EF) and shortening fractions in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients treated with anthracyclines [26]. Another ABCC5 variant, rs939338, is associated with lower 5-year progression-free survival in osteosarcoma patients [38].

Genetic variants affecting DOX pharmacodynamic pathways

Four major mechanisms of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity have been identified: the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), TOP2B inhibition, and mitochondrial and calcium dysregulation.

One of the major sources of ROS involves a reaction catalyzed by the multi-subunit enzyme NADPH oxidase, involving the 1-electron reduction of oxygen through the usage of NADPH (and NADH) as the electron donor. NADPH oxidase consists of six subunits RAC1/RAC2, CYBA, NOX2, NCF1, NCF2 and NCF4 [39,40]. NADPH oxidase activity has a established role in DIC and NOX2 knockout mice, which show a significant reduction NADPH oxidase activity, have been shown to be protected against DIC when compared with wild-type mice [34]. Consistent with these experimental findings, Wojnowski et al. reported that genetic polymorphisms in NADPH oxidase subunits are associated with AIC. In that, rs4673 in CYBA is associated with chronic DIC, whereas variants rs1883112 and rs13058338 in NCF4 and RAC2, respectively, are associated with acute DIC (Figure 2) [34].

A second source of ROS is from the interaction of DOX with iron to form DOX-iron complexes that subsequently increase the magnitude of DIC [41]. Patients treated with a cumulative DOX dose of more than 200 mg/m2 have been shown to experience a higher concentration of myocardial iron [42]. The gene HFE encodes the human homeostatic iron regulator protein that regulates iron transport and metabolism. Impaired HFE function leads to hemochromatosis that is associated with excess iron deposition in major tissues including the heart. Miranda et al. demonstrated that the alteration in DOX-induced iron metabolism was intensified in HFE knockout mice due to the accumulation of a higher amount of iron in murine hearts. Furthermore, they showed that HFE-deficient mice were more sensitive to DOX-induced elevations in serum creatine kinase and aspartate aminotransferase, showed increased mortality rate and a higher degree of mitochondrial damage when compared with wild-type mice [43]. Moreover, variants in HFE including rs1799945 and rs1800562 were associated with a higher incidence of symptomatic heart failure [44] and DOX-associated myocardial injury [45], respectively, after DOX treatment (Figure 2).

Several proteins act as a defensive mechanisms to protect cardiomyocytes from ROS and initiate DNA repair after ROS-induced DNA damage including, CAT, GSTP1, HAS3 and ERCC2 that is involved in nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway.

CAT is an enzyme that catalyzes the decomposition of a major source of ROS, converting hydrogen peroxide into water and hydrogen. The variant rs1001179 in the promoter region of CAT is associated with a reduction in the catalytic activity of CAT in a genotype dose-dependent manner [46]. Rajic et al. reported that this SNP is associated with severe cardiac damage after anthracycline exposure in 76 long-term survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood [47].

The GST family consists of several detoxification enzymes that catalyze the conjugation of glutathione to anthracyclines active electrophilic metabolites rendering them inactive and thus protect the cell against ROS [48]. There are two glutathione-S-transferase isoforms, the membrane-bound and the cytosolic, the latter of which includes highly polymorphic genes that are divided into six classes, GSTA1-5 (alpha), GSTK1 (kappa), GSTM1-5 (mu), GSTO1-2 (omega), GSTP1 (pi), GSTT1-4 (theta), GSTZ1 (zeta). Notably, SNP rs1695 (I105V) in GSTP1 is associated with tumor response to anthracycline-based chemotherapy and dose delay/reduction due to neutropenia in invasive breast carcinoma patients (Figure 2) [49]. GSTM1 null genotype (homozygous deletion of the gene) was found to be associated with abolished enzymatic activity [50]. Recently, Singh et al. demonstrated that GSTM1 null genotype is associated with an increased risk of cardiomyopathy in childhood cancer survivors treated with anthracyclines. Functional validation in hiPSC-CMs derived from anthracycline-treated patients who had cardiomyopathy showed a reduced GSTM1 expression when compared with hiPSC-CMs derived from anthracycline-treated patients who did not experience cardiomyopathy [51].

Hyaluronan (HA) is a component of the cardiac extracellular matrix that surrounds the myocardial cells including, cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts and endothelium. HA plays multiple roles in both cardiac development and in cardiac remodeling as a result of cardiac injuries such as valvular regurgitation, hypertension, dilated cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction and myocarditis [52]. Petz et al. showed that increased HA synthesis enhanced postinfarct healing by supporting the macrophage survival and by promoting the myofibroblast response [53]. HAS3 encodes for hyaluronan synthase 3 enzyme that is responsible for HA synthesis. Patients harboring the AA genotype of SNP rs2232228 in HAS3 that is associated with lower HAS3 expression experienced a ninefold increased risk of cardiomyopathy after anthracycline treatment when compared with patients with GA genotype (Figure 2) [54].

The NER pathway is responsible for the repairing of several forms of DNA damage including cross-links, adducts and oxidative damages. As an essential step of NER pathway, the general transcription factor IIH protein complex unwinds DNA-double strands to facilitate DNA repair. ERCC2 gene encodes for the a helicase subunit that plays an important role in stabilizing the transcription factor IIH core complex. Interestingly, nonsynonymous variants rs13181 (K751Q) and rs1799793 (D312N) in ERCC2 are associated with lower DNA repair capacity [55] and with increased risk of different types of cancer [56]. Furthermore, rs13181 is associated with both chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity and a lower chance of achieving a response to induction chemotherapy [57].

TOP2A and TOP2B are enzymes that cause double-stranded cuts required for unwinding DNA during the process of DNA replication and transcription and thus important for cancer cell proliferation. The mechanism by which anthracyclines exert their cytotoxic action is through TOP2A inhibition resulting in unrepaired DNA cuts leading to programmed cancer cell death. Similarly, DOX binds to and inhibits the cardiac-specific TOP2B in cardiomyocytes, which in turn induces DNA double-strand break-triggered cardiac cell apoptosis. Zhang et al. showed that cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of TOP2B protects mice from the development of DOX-induced progressive heart failure [58]. Moreover, the expression of TOP2B is regulated by RARG, in that RARG activation results in the repression of TOP2B in rat cardiomyoblasts [59]. Importantly, a coding a nonsynonymous variant in RARG, rs2229774 (S427L) is associated with AIC (Figure 2). Functional validation of this association revealed that the S427L variant is associated with a significant reduction in RARG-induced TOP2B repression [59].

Finally, DOX stimulates Ca2+ release and inhibits Ca2+ reuptake in RYR2 and blocking ATP2A2, respectively, that results in calcium dysregulation-driven cardiotoxicity [18,60]. The damaging effect of anthracyclines on sarcomeres was demonstrated by analyzing left ventricular endomyocardial biopsies from patients with DIC that showed myofibrillar loss in the sarcomere and endocardial fibrosis [61]. MHY7 encodes the thick filament sarcomeric protein, myosin heavy chain-β that plays an important role in energy transduction and force development in the human heart. Paalberend et al. showed that variants in MYH7 are associated with hypocontractile sarcomeres, lower maximal force-generating capacity and more severe cardiomyocytes remodeling [62]. Interestingly, genetic screening in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and DIC revealed the presence of two MYH7 nonsynonymous SNPs, rs564101364 (D545N) and rs886039204 (D955N), emphasizing the role of MYH7 genetic polymorphisms in DIC susceptibility.

The thin filament sarcomeric TNNT2 controls the cardiac muscle cells contraction through controlling cell response toward altered Ca2+ concentration. During development, TNNT2 is transcribed into two different isoforms, the fetal longer isoform that includes an additional exon (exon 5) and the adult shorter isoform. These two isoforms are generated by muscle-specific splicing enhancers (MSE)-dependent alternative splicing of exon 5 and confer different levels of sensitivity toward intracellular calcium concentration and consequently different contractility profiles during the maturation of cardiac cells. Thus, the coexpression of the two isoforms leads to a split response toward [Ca2+], which in turn results in lower myocardial contractility and inefficient ventricular pumping capacity, and eventually a failed heart [63]. CELF4 is a MSEs-containing RNA binding protein that regulates alternative splicing of several proteins. In the human heart, CELF4 binds to a conserved CUG motif in TNNT2 MSE that is located within introns flanking exon 5 and developmentally regulates the inclusion of ten amino acids constituting exon 5. Interestingly, the GG genotype of the CELF4 intronic variant, rs1786814 is associated with the coexistence of more than one TNNT2 splicing variants, and with more the tenfold higher risk to develop cardiotoxicity in patients exposed to 300 mg/m2 or less of anthracycline (Figure 2) [64].

Using hiPSC-CMs to validating the genomic basis of patient-specific susceptibility to DIC

The vast majority of candidate gene- or genome-wide-based DIC pharmacogenomic studies use genotyping chips that specifically capture several preselected Tag SNPs. Tag SNPs are SNPs in perfect linkage disequilibrium with many other neighboring SNPs and act as surrogates for their detection. Unsurprisingly, identified variants that are statistical associated with DIC are always coinherited (linked) with several other SNPs that have indistinguishable statistical associations with DIC. Accordingly, DIC genotype–phenotype association studies require downstream fine-mapping to identify the actual causal SNP that can then be mechanistically validation [65]. Recently, we developed a Nanopore sequencing-based pipeline that enhances the fine-mapping of GWAS-identified DIC-associated loci and prioritizes potential causal SNP(s) with a minimal cost of approximately $10/100 kb of associated DIC loci/sample [66]. Coupling this pipeline with a patient-specific cell model that can recapitulate intraindividual variability across the population in susceptibility to cardiotoxic events can help unravel the genetic causes of DIC and eventually provide personalized diagnostic and treatment strategies for DIC.

hiPSC-CM as a platform to phenotype patient-specific drug responses

hiPSCs have been differentiated into a wide variety of lineages and have been extensively used in disease modeling. Patient-specific hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) have been successfully employed to provide fundamental and mechanistic understanding of a wide variety of cardiovascular diseases, including long QT syndrome [67,68], LEOPARD syndrome [69], Timothy syndrome [70], arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy [71], dilated cardiomyopathy [72], Barth syndrome [73], coronary artery diseases [74] and diabetic cardiomyopathy [75]. Huge efforts have been devoted to enhancing the robustness, purity and scalability of hiPSC cardiac differentiation resulting in modern chemically defined and animal product-free methodologies that facilitate the usage of these cells at scale and under GMP conditions [76].

Cardiomyocyte maturation underlines all morphological, transcriptional, metabolic, electric and functional properties of adult heart cells. Thus, maturation of hiPSC-CMs is indispensable to accurately recapitulate cardiac pharmacological drug responses in adults. Several methods have been adopted to promote hiPSC-CM maturation, including patterning of cardiomyocytes to adopt a rod-shaped morphology, application of cyclic mechanical stress during systole and passive stretch during diastole, increasing the number of days in culture media, electrical pacing, hormonal maturation using triiodothyronine, IGF1 and the glucocorticoid dexamethasone, and increasing the oxygen tension [77]. These maturation methods have shown that it is feasible to generate mature hiPSC-CMs that resemble adult heart cells in all aspects including, structural maturity, sarcomere organization, Ca2+ handling, transcription profile associated with adult heart cells, electrophysiological maturation and contractility [77]. Despite this progress, it is still not clear what level of maturation is required for hiPSC-CMs to accurately recapitulate patient-specific cardiotoxicity responses to DOX.

The ability to generate millions of cardiomyocytes cost-effectively is crucial for the efficient utilization of hiPSC-CMs as a DOX-response assay platform. Large-scale cardiac differentiation protocols have been significantly improved overtime starting with the production of approximately 15 million cardiomyocytes from a 6-well plate, passing through using larger formats such as 15 cm plates or T flasks that generate 50–150 million cardiomyocytes per batch. Recently, 4 × 150 ml parallel bioreactor-based differentiations were shown to produce more than 240 million cardiomyocytes in 22 days [78].

hiPSC-CMs can be plated into 384-well format that is compatible with industry-standard techniques for measuring cardiomyocyte drug response, such as luminescent measurement of viability, caspase activity as a marker for apoptosis and ROS production. For cell dye-based assays such as mitochondrial membrane potential and superoxide production, high-throughput flow cytometry can be performed in at least a 96-well format. Automated high-content imaging is most suitable for high-throughput analysis of the changes in cell size or proportions, lipogenesis and sarcomere alignment. High-throughput kinetic image cytometry combined with calcium-sensitive dyes such as Calbryte 520 and Fura-2 or genetically encoded calcium indicators such as R-GECO and GCaMP6f is suitable for assessing the effects of drugs on calcium-handling voltage. Multiwell microelectrode array (MEA) technology is suitable for the analysis of extracellular field potentials as well as extracellular action potentials when MEA is coupled to a cardiomyocyte syncytium [79]. Finally, the high-throughput measurement of drug effects on metabolic parameters such as mitochondrial function and substrate use is possible in up to 96-well format using the seahorse extracellular flux analyzer [80].

hiPSC-CMs model to study chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity

Several research groups have successfully used hiPSC-CMs to study drug-induced cardiotoxicity. Burridge et al. demonstrated that patient-specific hiPSC-CMs recapitulate breast cancer patient susceptibility to DIC. In that, hiPSC-CMs generated from breast cancer patients who have been treated with DOX and experienced severe DIC were more sensitive to DOX as compared with hiPSC-CMs derived from breast cancer patients who have been treated with DOX but did not experience any DIC. Using a wide array of DIC in vitro characterization they showed that this higher sensitivity to DOX was due to significant impaired mitochondrial and metabolic function and impaired calcium handling [81]. Furthermore, Adamcova et al. provided evidences for the existence of dose-dependent changes in the metabolism, cell membrane permeability and cell death in hiPSC-CMs exposed acutely and chronically to DOX [82]. Sharma et al. used hiPSC-CMs to assess the cardiotoxicity of 21 US FDA-approved tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in addition to DOX. They assessed drug-induced cardiotoxicity by measuring alterations in cardiomyocyte viability, contractility, electrophysiology, calcium handling and signaling from which they generated a cardiac safety index that ranges between 0 and 1 for each drug. Out of the investigated drugs, they showed that DOX, nilotinib and vandetanib are the most cardiotoxic molecules with a cardiac safety index of ≤0.01 [83]. In another study, Shafaattalab et al. showed that the ibrutinib-induced atrial fibrillation is associated with cell-type-specific cardiotoxic effects. Treating atrial hiPSC-CMs with ibrutinib results in a significant and dose-dependent decrease in action potential duration at 80% of repolarization (APD80). On contrary, ibrutinib does not have a significant effect on APD80 ventricular hiPSC-CMs [84]. Lee et al. investigated the cardiotoxicity molecular mechanism of another multikinase inhibitor, vandetanib using intracellular electrophysiological recordings on hiPSC-CMs. The authors showed that hiPSC-CMs were more sensitive to inhibition of the inward Na+ current (INa) by vandetanib than in a heterogeneously expressed HEK293 cell model, consistent with the changes in the action potential parameters of hiPSC-CMs [85]. Wang et al. showed that treating hiPSC-CMs with a different TKI, sorafenib results in the downregulation of oxidative phosphorylation that eventually leads to a defect in mitochondrial energetics [86]. Trastuzumab is another anticancer agent that is associated with cardiac toxicity. Kitani et al. used hiPSC-CMs to study the underlying cellular mechanism of trastuzumab-induced cardiac dysfunction [87]. The authors showed that trastuzumab treatment significantly reduced the contraction velocity and deformation distance in the breast cancer patients-derived hiPSC-CM that had a severe trastuzumab-induced LVEF decline as compared with those who did not experience any LVEF decline after having the same trastuzumab dose. On the contrary, Kurokawa et al. demonstrated that the cardiotoxic effects of ERBB2 inhibition by trastuzumab can be recapitulated in patients-derived hiPSC-CMs only after DOX-induced cellular stress [88]. HSU et al. showed that lapatinib which is a crucial alternative to trastuzumab that is commonly used in combination with DOX, synergistically increased DOX toxicity in hiPSC-CMs in a dose- and time-dependent manner. The authors then showed that this damaging effect is due to an increased inducible NOS (iNOS) expression and pronounced production of NO [89]. Interestingly, Toshikatsu et al. developed a 2D morphological assessment system to predict drug-induced cardiotoxicity in cancer patients using hiPSC-CMs. The authors tested their system to predict induced cardiotoxicity that results after treatment of 28 different drugs and the assay showed 81% sensitivity and 100% specificity [90].

Using hiPSC-CMs to validate the variant-specific response to DIC

The fact the patient-derived hiPSC-CMs carry the exact DNA signature of the patient from whom they were generated has made it an invaluable tool in personalized medicine and pharmacogenomics. The identification of causal genetic variants that increase or decrease the susceptibility of a specific patient and/or population to DIC is essential, as testing for the causal variant guarantees the detection of the best possible association in clinical practice. Additionally, the identification of causal polymorphisms in druggable targets can be followed by drug screening to develop safe and effective cardioprotective drugs.

The momentous advances in the field of genomic editing coupled to hiPSC technology have further facilitated the study of the functional repercussion and the causality of a particular variant on DIC phenotype. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated (Cas) adaptive immune systems can be used to specifically knockout certain genes, introducing a pathogenic variant allele and reverting a variant allele to the wild-type allele. CRISPR/Cas9-based knockout in hiPSC-CMs can be the initial functional validation of a DIC-associated candidate gene. Cas9 nuclease protein can be guided to a specific target locus by a 20-bp long protospacer oligos (aka single-guide RNA, sgRNA), which identifies a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) that is located 3-bp downstream where the Cas9 introduces a cut. Afterward, cells adopt mainly a nonhomologous end joining-derived DNA repair pathway in an attempt to repair the introduced DNA cut. Nonhomologous end joining is an error-prone approach that usually introduces indels that result in a frameshift mutation and eventually leads to an efficient knockout of a particular gene. Targeting candidate gene constitutively expressed exons close to the transcription start site (ATG) results in a truncated nonfunctional isoform of that gene. Interestingly, using two gRNAs that are 30–40 bp apart, we were able to introduce out of frame deletions of more than 80 bp [Unpublished Data]. Disruption on the DNA level in positively knocked out clones is then confirmed using Sanger sequencing followed by RT-qPCR to confirm the deleterious effect of introduced indels on the expression of the relevant gene.

Similarly, CRISPR/Cas9-based genomic editing can be used to validate potential causal DIC-associated variants in hiPSC-CMs. CRISPR/Cas9-based SNP editing can be done by electroporating hiPSCs with a plasmid expressing the nuclease Cas9 and an antibiotic-resistant gene, gRNA that guides the Cas9 to target locus, homology-directed repair (HDR) template that is utilized by hiPSCs to repair the introduced DNA cut. Antibiotic selection of the positively nucleofected cells starts 48-h postelectroporation. Single hiPSC clones are then picked and sequenced to confirm positively edited hiPSC clones. The HDR template is a single- or double-stranded oligonucleotide donor DNA (ds/ssODN) that carries the desired modification to introduce flanked by segments of DNA (50–80 bp) that are homologous to the blunt ends of the cleaved DNA. Importantly, the PAM sequence in the HDR template should be modified by introducing a blocking mutation otherwise, CRISPR/Cas9 will keep cutting the HDR template and fails the editing process. SNP-editing efficiency relies on whether or not hiPSCs adopt HDR pathway to repair the cleaved DNA. Significant efforts have been made and indeed succeeded in increasing the efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9-directed genomic editing. Targeting the DNA at cut-to-mutation distance of less than 5–10 bp significantly improves SNP-editing efficiency by multiple folds. Using gBlock-based in vitro expression of a modified sgRNA with an AU flip and extended stem increases the sgRNA stability and improved SNP-editing efficiency [91,92]. Similarly, Richardson et al. showed that asymmetric homology arms (36 bases distal to the PAM and 91 bases proximal to the PAM) result in a 60% increase in genomic editing [93].

Base editing represents another novel technology that can be used to edit a specific variant in hiPSCs. Base editors were first developed in 2016 and are composed of Cas9 nickase or catalytically inactive ‘dead’ Cas9 (dCas9) fused to either cytidine deaminase or adenine deaminase generating the two main types of base editors, cytosine base editors (CBE) and adenine base editors (ABE). CBEs convert C•G base pair to a T•A base pair, whereas ABEs convert A•T base pair into a G•C base pair and hence collectively, CBEs and ABEs can mediate all four possible transition mutations (C to T, A to G, T to C and G to A). These transitions constitute about 61% of known pathogenic variants and thus 20,580 SNPs out of 33,739 known pathogenic variants can be edited using this approach [94]. Unlike the HDR template-based genomic editing, base editors do not induce any DNA double-strand cleavage and alternatively, they utilize the deamination capacity of CBEs and ABEs. CBEs deaminate cytidine into uridine, which is subsequently converted to thymidine through base excision repair, creating a C to T change (or a G to A on the reverse strand), while ABEs deaminate adenosine to inosine, which is treated like guanosine by the cell and thus base pairs with a cytidine. Each base editor has its own catalytic activity window that is the sequence within which a particular base edit can exert its action and is generally located at positions approximately 4–8, counting the PAM as positions 21–23 [94]. Tremendous advances in this relatively new technology have resulted in the development of many base editors that have a wide range of catalytic activity windows such as SA(KKH)-BE3 (positions 3–12), Target-AID (position 2–4) and VQR-ABE (position 4–6) [95]. Importantly, researchers have developed different Cas9 nuclease enzymes that recognize a wide variety of PAM sequences, increasing the number of targetable bases. Currently, available base editors can recognize a broad range of PAM sequences including but not limited to: NGG, NG, NNGRRT, NNNRRT, TTV, NGA, NGCG and NGAN. Recently, Walton et al. developed a near-PAM-less SpCas9 variant that when fused to a base-editor variant can target almost all PAMs [96]. Taken together, combining the HDR-based and base-editor-based genomic editing approaches has made it feasible to edit nearly all target pathogenic variants.

Conclusion

DOX has been widely used to treat multiple types of cancer for more than 50 years and has contributed to a significant increase in the survival rate in cancer patients. However, DIC limits the chemotherapeutic utility of this potent drug and represents a persistent challenge in the field of cardio-oncology. Many genotype–phenotype association studies have identified numerous loci associated with DIC, however, the true link between these loci and DIC has not been yet established. As a result, there are currently no FDA-approved DIC-related genomic biomarkers being used in routine clinical practice, and only a single on-market drug, dexrazoxane is approved to potentially decrease the incidence of DIC. Patient-specific hiPSC-CMs represents a high-throughput compatible cell model that harbor patient-specific genetic makeup. The immense advances in cardiac differentiation, maturation and scalability protocol have increased the feasibility of generating billions of hiPSC-CMs that recapitulate native cardiomyocyte electrophysiological, biochemical, contractile and beating activity. The continuous development of genomic editing technologies has made it possible to edit candidate SNPs in hiPSC-CMs. Taking together, pairing candidate variants editing technology with high-throughput DIC phenotypic characterization in hiPSC-CMs could help explicate the genomic predisposition to DIC.

Future perspective

The substantial evolution in all aspects of the field of personalized medicine and pharmacogenomics including high-depth sequencing technologies, analysis pipelines and data storage capacity has culminated in cost-effective, fast and efficient sequencing of the human genomes. This increase in accessibility of whole-genome sequencing allows the future completion of pharmacogenomic studies that can comprehensively identify genomic loci that play a role in DIC. Yet this identification of interesting loci must be complemented by downstream functional validations in hiPSC-CMs as they recapitulate variant and patient-specific pharmacological and toxicological responses. This complementary validation can be conducted via two steps approach: first, by knocking down and overexpressing a particular DIC-associated locus, and second by introducing candidate causal SNP in an isogenic hiPSC-CMs or correcting a risk allele in a patient cell line. Both of these steps are now feasible with recent improvements in CRISPR-based technology. The characterization of DIC phenotypes in these genetically engineered patient-derived heart cells will accelerate the inclusion of FDA-approved DIC predictive biomarkers in routine clinical practice. Similarly, understanding of the genomic basis of DIC will provide genetically informed individualized anthracycline dosing to provide the patient with the maximum efficacy and minimal side effects.

Executive summary.

Anthracyclines are potent anticancer agents, however, they are associated with dose-dependent cardiac toxicity that limits their utility.

Pharmacogenomic studies have identified about 60 loci across the human genome that are associated with anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity.

The vast majority of these studies lack any downstream functional validation and leave us without any US FDA-approved DIC-related genomic biomarkers being used in routine clinical practice and only a single on-market drug, dexrazoxane is approved to potentially decrease the incidence of DIC.

Patient-derived human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) harboring patient-specific genetic makeup are an invaluable tool in the field of personalized medicine and have been successfully employed to study basal mechanisms and to provide a fundamental and mechanistic understanding of a wide variety of cardiovascular diseases and drug-induced cardiotoxicity.

The immense advances in somatic cell reprogramming, hiPSC culture, cardiac differentiation, maturation and protocol scalability have increased the feasibility of generating billions of hiPSC-CMs that recapitulate native cardiomyocyte electrophysiological, biochemical, contractile and beating activity.

Identification of loci associated with drug-induced cardiotoxicity must be complemented by downstream functional validations in hiPSC-CMs as they recapitulate variant and patient-specific pharmacological and toxicological responses.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work is funded by Fondation Leducq (http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/501100001674) and the National Cancer Institute (http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/100000054, R01-CA220002). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Lipshultz SE, Alvarez JA, Scully RE. Anthracycline associated cardiotoxicity in survivors of childhood cancer. Heart 94(4), 525–533 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avila MS, Ayub-Ferreira SM, De Barros Wanderley MR et al. Carvedilol for prevention of chemotherapy-related cardiotoxicity: the CECCY trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 71(20), 2281–2290 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Muñoz D et al. 2016 ESC position paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: the task force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 37(36), 2768–2801 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wouters KA, Kremer LCM, Miller TL, Herman EH, Lipshultz SE. Protecting against anthracycline-induced myocardial damage: a review of the most promising strategies. Br. J. Haematol. 131(5), 561–578 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer 97(11), 2869–2879 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Pal HJ, van Dalen EC, Hauptmann M et al. Cardiac function in 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: a long-term follow-up study. Arch. Intern. Med. 170(14), 1247–1255 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barpe DR, Rosa DD, Froehlich PE. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of doxorubicin plasma levels in normal and overweight patients with breast cancer and simulation of dose adjustment by different indexes of body mass. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 41(3–4), 458–463 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gianni L, Vigano L, Locatelli A et al. Human pharmacokinetic characterization and in vitro study of the interaction between doxorubicin and paclitaxel in patients with breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 15(5), 1906–1915 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mross K, Maessen P, van der Vijgh WJ, Gall H, Boven E, Pinedo HM. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of epidoxorubicin and doxorubicin in humans. J. Clin. Oncol. 6(3), 517–526 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoglund PJ, Nordstrom KJ, Schioth HB, Fredriksson R. The solute carrier families have a remarkably long evolutionary history with the majority of the human families present before divergence of Bilaterian species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28(4), 1531–1541 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visscher H, Ross CJD, Rassekh SR et al. Pharmacogenomic prediction of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in children. J. Clin. Oncol. 30(13), 1422–1428 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visscher H, Ross CJD, Rassekh SR et al. Validation of variants in SLC28A3 and UGT1A6 as genetic markers predictive of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in children. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 60(8), 1375–1381 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lal S, Wong ZW, Jada SR et al. Novel SLC22A16 polymorphisms and influence on doxorubicin pharmacokinetics in Asian breast cancer patients. Pharmacogenomics 8(6), 567–575 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bray J, Sludden J, Griffin MJ et al. Influence of pharmacogenetics on response and toxicity in breast cancer patients treated with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. Br. J. Cancer 102(6), 1003–1009 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aminkeng F, Ross CJD, Rassekh SR et al. Recommendations for genetic testing to reduce the incidence of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 82(3), 683–695 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Licata S, Saponiero A, Mordente A, Minotti G. Doxorubicin metabolism and toxicity in human myocardium: role of cytoplasmic deglycosidation and carbonyl reduction. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 13(5), 414–420 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joerger M, Huitema ADR, Meenhorst PL, Schellens JHM, Beijnen JH. Pharmacokinetics of low-dose doxorubicin and metabolites in patients with AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 55(5), 488–496 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mushlin PS, Cusack BJ, Boucek RJ Jr, Andrejuk T, Li X, Olson RD. Time-related increases in cardiac concentrations of doxorubicinol could interact with doxorubicin to depress myocardial contractile function. Br. J. Pharmacol. 110(3), 975–982 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez-Covarrubias V, Zhang J, Kalabus JL, Relling MV, Blanco JG. Pharmacogenetics of human carbonyl reductase 1 (CBR1) in livers from black and white donors. Drug Metab. Dispos. 37(2), 400–407 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jordheim LP, Ribrag V, Ghesquieres H et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in ABCB1 and CBR1 can predict toxicity to R-CHOP type regimens in patients with diffuse non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Haematologica 100(5), e204–e206 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lakhman SS, Ghosh D, Blanco JG. Functional significance of a natural allelic variant of human carbonyl reductase 3 (CBR3). Drug Metab. Dispos. 33(2), 254–257 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanco JG, Sun CL, Landier W et al. Anthracycline-related cardiomyopathy after childhood cancer: role of polymorphisms in carbonyl reductase genes--a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 30(13), 1415–1421 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hertz DL, Caram MV, Kidwell KM et al. Evidence for association of SNPs in ABCB1 and CBR3, but not RAC2, NCF4, SLC28A3 or TOP2B, with chronic cardiotoxicity in a cohort of breast cancer patients treated with anthracyclines. Pharmacogenomics 17(3), 231–240 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Li L, Ding X, Kaminsky LS. Identification of cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase gene variants that are significantly associated with the interindividual variations in warfarin maintenance dose. Drug Metab. Dispos. 39(8), 1433–1439 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lubieniecka JM, Graham J, Heffner D et al. A discovery study of daunorubicin induced cardiotoxicity in a sample of acute myeloid leukemia patients prioritizes P450 oxidoreductase polymorphisms as a potential risk factor. Front. Genet. 4( 231), 231–241 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krajinovic M, Elbared J, Drouin S et al. Polymorphisms of ABCC5 and NOS3 genes influence doxorubicin cardiotoxicity in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pharmacogenomics J. 16(6), 530–535 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwuchukwu OF, Ajetunmobi J, Ung D, Nagar S. Characterizing the effects of common UDP glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A6 and UGT1A1 polymorphisms on cis- and trans-resveratrol glucuronidation. Drug Metab. Dispos. 37(8), 1726–1732 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nies AT, Magdy T, Schwab M, Zanger UM. Role of ABC transporters in fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy response. Adv. Cancer Res. 125, 217–243 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magdy T, Arlanov R, Winter S et al. ABCC11/MRP8 polymorphisms affect 5-fluorouracil-induced severe toxicity and hepatic expression. Pharmacogenomics 14(12), 1433–1448 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang B, Yan LJ, Wu Q. ABCB1 (C1236T) Polymorphism affects P-glycoprotein-mediated transport of methotrexate, doxorubicin, actinomycin D, and etoposide. DNA Cell Biol. 38(5), 485–490 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikeda M, Tsuji D, Yamamoto K et al. Relationship between ABCB1 gene polymorphisms and severe neutropenia in patients with breast cancer treated with doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 30(2), 149–153 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gregers J, Gréen H, Christensen IJ et al. Polymorphisms in the ABCB1 gene and effect on outcome and toxicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pharmacogenomics J. 15(4), 372–379 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sampson A, Peterson BG, Tan KW, Iram SH. Doxorubicin as a fluorescent reporter identifies novel MRP1 (ABCC1) inhibitors missed by calcein-based high content screening of anticancer agents. Biomed. Pharmacother. 118, 109289 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wojnowski L, Kulle B, Schirmer M et al. NAD(P)H oxidase and multidrug resistance protein genetic polymorphisms are associated with doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Circulation 112(24), 3754–3762 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Folmer Y, Schneider M, Blum HE, Hafkemeyer P. Reversal of drug resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by adenoviral delivery of anti-ABCC2 antisense constructs. Cancer Gene Ther. 14(11), 875–884 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung KA, Choi BH, Kwak MK. The c-MET/PI3K signaling is associated with cancer resistance to doxorubicin and photodynamic therapy by elevating BCRP/ABCG2 expression. Mol. Pharmacol. 87(3), 465–476 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lal S, Sutiman N, Ooi LL et al. Pharmacogenetics of ABCB5, ABCC5 and RLIP76 and doxorubicin pharmacokinetics in Asian breast cancer patients. Pharmacogenomics J. 17(4), 337–343 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hagleitner MM, Coenen MJH, Gelderblom H et al. A first step toward personalized medicine in osteosarcoma: pharmacogenetics as predictive marker of outcome after chemotherapy-based treatment. Clin. Cancer Res. 21(15), 3436–3441 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li JM, Gall NP, Grieve DJ, Chen M, Shah AM. Activation of NADPH oxidase during progression of cardiac hypertrophy to failure. Hypertension 40(4), 477–484 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopes LR, Dagher MC, Gutierrez A et al. Phosphorylated p40PHOX as a negative regulator of NADPH oxidase. Biochemistry 43(12), 3723–3730 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gammella E, Maccarinelli F, Buratti P, Recalcati S, Cairo G. The role of iron in anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Front. Pharmacol. 5, 25 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cascales A, Sánchez-Vega B, Navarro N et al. Clinical and genetic determinants of anthracycline-induced cardiac iron accumulation. Int. J. Cardiol. 154(3), 282–286 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miranda CJ, Makui H, Soares RJ et al. Hfe deficiency increases susceptibility to cardiotoxicity and exacerbates changes in iron metabolism induced by doxorubicin. Blood 102(7), 2574–2580 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Armenian SH, Ding Y, Mills G et al. Genetic susceptibility to anthracycline-related congestive heart failure in survivors of haematopoietic cell transplantation. Br. J. Haematol. 163(2), 205–213 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lipshultz SE, Lipsitz SR, Kutok JL et al. Impact of hemochromatosis gene mutations on cardiac status in doxorubicin-treated survivors of childhood high-risk leukemia. Cancer 119(19), 3555–3562 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahn J, Nowell S, Mccann SE et al. Associations between catalase phenotype and genotype: modification by epidemiologic factors. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15(6), 1217–1222 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rajić V, Aplenc R, Debeljak M et al. Influence of the polymorphism in candidate genes on late cardiac damage in patients treated due to acute leukemia in childhood. Leuk. Lymphoma 50(10), 1693–1698 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Townsend DM, Tew KD. The role of glutathione-S-transferase in anti-cancer drug resistance. Oncogene 22(47), 7369–7375 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tulsyan S, Chaturvedi P, Agarwal G et al. Pharmacogenetic influence of GST polymorphisms on anthracycline-based chemotherapy responses and toxicity in breast cancer patients: a multi-analytical approach. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 17(6), 371–379 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu X, Li G, Zhou X et al. Improving editing efficiency for the sequences with NGH PAM using xCas9-derived base editors. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 17, 626–635 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh P, Wang X, Hageman L et al. Association of GSTM1 null variant with anthracycline-related cardiomyopathy after childhood cancer-a Children's Oncology Group ALTE03N1 report. Cancer 126(17), 4051–4058 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suleiman M, Abdulrahman N, Yalcin H, Mraiche F. The role of CD44, hyaluronan and NHE1 in cardiac remodeling. Life Sci. 209, 197–201 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petz A, Grandoch M, Gorski DJ et al. Cardiac hyaluronan synthesis is critically involved in the cardiac macrophage response and promotes healing after ischemia reperfusion injury. Circ. Res. 124(10), 1433–1447 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang X, Liu W, Sun CL et al. Hyaluronan synthase 3 variant and anthracycline-related cardiomyopathy: a report from the children's oncology group. J. Clin. Oncol. 32(7), 647–653 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spitz MR, Wu X, Wang Y et al. Modulation of nucleotide excision repair capacity by XPD polymorphisms in lung cancer patients. Cancer Res. 61(4), 1354–1357 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benhamou S, Sarasin A. ERCC2/XPD gene polymorphisms and cancer risk. Mutagenesis 17(6), 463–469 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.El-Tokhy MA, Hussein NA, Bedewy AM, Barakat MR. XPD gene polymorphisms and the effects of induction chemotherapy in cytogenetically normal de novo acute myeloid leukemia patients. Hematology (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) 19(7), 397–403 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang S, Liu X, Bawa-Khalfe T et al. Identification of the molecular basis of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat. Med. 18(11), 1639–1642 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aminkeng F, Bhavsar AP, Visscher H et al. A coding variant in RARG confers susceptibility to anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in childhood cancer. Nat. Genet. 47(9), 1079–1084 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hanna AD, Lam A, Tham S, Dulhunty AF, Beard NA. Adverse effects of doxorubicin and its metabolic product on cardiac RyR2 and SERCA2A. Mol. Pharmacol. 86(4), 438–449 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mortensen SA, Olsen HS, Baandrup U. Chronic anthracycline cardiotoxicity: haemodynamic and histopathological manifestations suggesting a restrictive endomyocardial disease. Br. Heart J. 55(3), 274–282 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Witjas-Paalberends ER, Piroddi N, Stam K et al. Mutations in MYH7 reduce the force generating capacity of sarcomeres in human familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Res. 99(3), 432–441 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gomes AV, Venkatraman G, Davis JP et al. Cardiac troponin T isoforms affect the Ca(2+) sensitivity of force development in the presence of slow skeletal troponin I: insights into the role of troponin T isoforms in the fetal heart. J. Biol. Chem. 279(48), 49579–49587 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang X, Sun CL, Quinones-Lombrana A et al. CELF4 variant and anthracycline-related cardiomyopathy: a Children's Oncology Group Genome-Wide Association Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 34(8), 863–870 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Magdy T, Burridge PW. The future role of pharmacogenomics in anticancer agent-induced cardiovascular toxicity. Pharmacogenomics 19(2), 79–82 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Magdy T, Kuo HH, Burridge PW. Precise and cost-effective nanopore sequencing for post-GWAS fine-mapping and causal variant identification. iScience 23(4), 100971 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Itzhaki I, Maizels L, Huber I et al. Modelling the long QT syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 471(7337), 225–229 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Malan D, Zhang M, Stallmeyer B et al. Human iPS cell model of type 3 long QT syndrome recapitulates drug-based phenotype correction. Basic Res. Cardiol. 111 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carvajal-Vergara X, Sevilla A, D'souza SL et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell derived models of LEOPARD syndrome. Nature 465(7299), 808–812 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yazawa M, Hsueh B, Jia X et al. Using iPS cells to investigate cardiac phenotypes in patients with Timothy syndrome. Nature 471(7337), 230–234 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim C, Wong J, Wen J et al. Studying arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia with patient-specific iPSCs. Nature 494(7435), 105–110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sun N, Yazawa M, Liu J et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells as a model for familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci. Transl. Med. 4(130), 130ra147 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang G, Mccain ML, Yang L et al. Modeling the mitochondrial cardiomyopathy of Barth syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cell and heart-on-chip technologies. Nat. Med. 20(6), 616–623 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Magdy T, Burridge PW. Unraveling difficult answers: from genotype to phenotype in coronary artery disease. Cell Stem Cell 24(2), 203–205 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Drawnel FM, Boccardo S, Prummer M et al. Disease modeling and phenotypic drug screening for diabetic cardiomyopathy using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Rep. 9(3), 810–821 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Burridge PW, Matsa E, Shukla P et al. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat. Methods 11(8), 855–860 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guo Y, Pu WT. Cardiomyocyte maturation: new phase in development. Circ. Res. 126(8), 1086–1106 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Halloin C, Coffee M, Manstein F, Zweigerdt R. Production of cardiomyocytes from human pluripotent stem cells by bioreactor technologies. Methods Mol. Biol. 1994, 55–70 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hayes HB, Nicolini AM, Arrowood CA et al. Novel method for action potential measurements from intact cardiac monolayers with multiwell microelectrode array technology. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 11893 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Magdy T, Schuldt AJT, Wu JC, Bernstein D, Burridge PW. Human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived cells to assess drug cardiotoxicity: opportunities and problems. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 6(58), 83–103 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Burridge PW, Li YF, Matsa E et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes recapitulate the predilection of breast cancer patients to doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat. Med. 22(5), 547–556 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Adamcova M, Skarkova V, Seifertova J, Rudolf E. Cardiac troponins are among targets of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in hiPCS-CMs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20(11), 2638–2651 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sharma A, Burridge PW, Mckeithan WL et al. High-throughput screening of tyrosine kinase inhibitor cardiotoxicity with human induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 9(377), 2584–2597 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shafaattalab S, Lin E, Christidi E et al. Ibrutinib displays atrial-specific toxicity in human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Reports 12(5), 996–1006 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee HA, Hyun SA, Byun B, Chae JH, Kim KS. Electrophysiological mechanisms of vandetanib-induced cardiotoxicity: comparison of action potentials in rabbit Purkinje fibers and pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS ONE 13(4), e0195577 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang H, Sheehan RP, Palmer AC et al. Adaptation of human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes to tyrosine kinase inhibitors reduces acute cardiotoxicity via metabolic reprogramming. Cell Syst. 8(5), 412–426.e417 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kitani T, Ong SG, Lam CK et al. Human-induced pluripotent stem cell model of trastuzumab-induced cardiac dysfunction in patients with breast cancer. Circulation 139(21), 2451–2465 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kurokawa YK, Shang MR, Yin RT, George SC. Modeling trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity in vitro using human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Toxicol. Lett. 285, 74–80 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hsu WT, Huang CY, Yen CYT, Cheng AL, Hsieh PCH. The HER2 inhibitor lapatinib potentiates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through iNOS signaling. Theranostics 8(12), 3176–3188 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Matsui T, Miyamoto K, Yamanaka K et al. Cell-based two-dimensional morphological assessment system to predict cancer drug-induced cardiotoxicity using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 383, 114761 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Arbab M, Srinivasan S, Hashimoto T, Geijsen N, Sherwood RI. Cloning-free CRISPR. Stem Cell Reports 5(5), 908–917 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen B, Gilbert LA, Cimini BA et al. Dynamic imaging of genomic loci in living human cells by an optimized CRISPR/Cas system. Cell 155(7), 1479–1491 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Richardson CD, Ray GJ, Dewitt MA, Curie GL, Corn JE. Enhancing homology-directed genome editing by catalytically active and inactive CRISPR-Cas9 using asymmetric donor DNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 34(3), 339–344 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rees HA, Liu DR. Base editing: precision chemistry on the genome and transcriptome of living cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19(12), 770–788 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dandage R, Despres PC, Yachie N, Landry CR. beditor: a computational workflow for designing libraries of guide RNAs for CRISPR-mediated base editing. Genetics 212(2), 377–385 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Walton RT, Christie KA, Whittaker MN, Kleinstiver BP. Unconstrained genome targeting with near-PAMless engineered CRISPR-Cas9 variants. Science 368(6488), 290–296 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]