Significance

The nature of Earth’s earliest crust is enigmatic due to the lack of a rock record for most of Earth’s first ∼600 My, the Hadean Eon. Studies have thus turned to scarce sites where Hadean detrital zircons have been discovered. The geochemistry of Hadean detrital zircon from a newly discovered site in South Africa suggests that the parental melts formed from variably hydrous melting of crust derived from the ambient mantle and show little evidence for an origin in arc-like settings. These results suggest that crust derived from ambient mantle played an important role during crust formation in the Hadean.

Keywords: Hadean, zircon, early Earth, crustal evolution

Abstract

The nature of Earth’s earliest crust and the processes by which it formed remain major issues in Precambrian geology. Due to the absence of a rock record older than ∼4.02 Ga, the only direct record of the Hadean is from rare detrital zircon and that largely from a single area: the Jack Hills and Mount Narryer region of Western Australia. Here, we report on the geochemistry of Hadean detrital zircons as old as 4.15 Ga from the newly discovered Green Sandstone Bed in the Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa. We demonstrate that the U-Nb-Sc-Yb systematics of the majority of these Hadean zircons show a mantle affinity as seen in zircon from modern plume-type mantle environments and do not resemble zircon from modern continental or oceanic arcs. The zircon trace element compositions furthermore suggest magma compositions ranging from higher temperature, primitive to lower temperature, and more evolved tonalite-trondhjemite-granodiorite (TTG)-like magmas that experienced some reworking of hydrated crust. We propose that the Hadean parental magmas of the Green Sandstone Bed zircons formed from remelting of mafic, mantle-derived crust that experienced some hydrous input during melting but not from the processes seen in modern arc magmatism.

Understanding the nature of Earth’s earliest crust and constraining the timing of early continent formation are crucial to modeling the evolution of the geodynamic system and the compositions of Earth’s early atmosphere and hydrosphere. Consensus over the nature of the earliest crust remains elusive. General models range from those suggesting an onset of continent formation (1, 2) and possible formation of arcs in a plate tectonic regime similar to that of today (3) shortly following Earths formation to studies suggesting that the earliest crust was overall more mafic than modern curst in composition and continents either rare or absent (4–7). Detrital zircons provide the only direct record of Earth’s first 500 million years of history. The most significant source of Hadean zircons are Archean sedimentary rocks in the Jack Hills and Mount Narryer region in Western Australia. Isolated Hadean zircons have also been found in a dozen other locations worldwide (8, 9). Of these locations, the Green Sandstone Bed (GSB) in the Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa, stands out with a total of 33 Hadean zircons discovered to date (10) (Datasets S1 and S2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The GSB is dated by the S6 spherule layer that lies 2 m below the GSB and has a depositional age of ∼3.31 Ga (11). The detrital zircons in the GSB show a major age peak at 3.38 Ga and include a significant number of zircons older than the oldest known igneous rocks and strata in the 3.55 to 3.22 Ga Barberton greenstone belt (10). In total, 0.5% of the analyzed zircons from the GSB are Hadean in age (10). Throughout its geological history, the GSB has experienced only lower greenschist-grade metamorphism (12, 13) and remains essentially unsheared. As a result, it contains well-preserved primary mineral grains.

While the crustal rocks in which Hadean zircon formed have been lost, the trace and rare earth element (REE) geochemistry of these zircons can be used to characterize their parental magma compositions. Zircon crystallizes as a ubiquitous accessory mineral in silica-rich, differentiated magmas formed in a number of crustal environments. Since zircon compositions are influenced by variations in melt composition, coexisting mineral assemblage, and trace element partitioning as a function of magmatic processes, temperature, and pressure (14–17), zircon geochemistry provides valuable constraints on magmatic compositions and processes at the time of zircon saturation. Consequently, trace element compositions of igneous and detrital zircon are a powerful tool that can be used to track melt evolution of individual magma bodies (18, 19) and changes within a tectono-magmatic system (20) or across an entire continent (21). Grimes et al. (16) pioneered the use of zircon trace element geochemistry to differentiate modern tectono-magmatic environments based on differences in source compositions (e.g., depleted versus undepleted mantle) and magmatic process (flux melting in arc settings) by using a family of discrimination diagrams. They used a compilation of ∼5,300 zircons from various crustal environments across the globe and found that, despite internal heterogeneity due to petrological processes, bivariate diagrams using U, Nb, Sc, Yb, Gd, and Ce can be used to distinguish between different tectono-magmatic settings, even if the crust experienced subsequent reworking within the same crustal setting.

In this study, we use the geochemistry of GSB Hadean zircons to characterize the compositions and possible sources of their parental magmas, highlight similarities and differences to zircon from Phanerozoic tectono-magmatic settings, and compare the results to the geochemistry of Hadean zircons from the Jack Hills to make broader inferences about the nature of Hadean crust and ultimately determine whether they originated from an arc or a relatively undepleted mantle environment.

Geochemistry of Hadean Zircons

Zircon texture and geochemistry have long been used to differentiate igneous from metamorphic zircon (22). Hadean zircons from the GSB show oscillatory and sector zoning typical of igneous zircon (10) (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). A total of five zircons show igneous cores with recrystallization rims indicative of metamorphic overgrowth. These rims were not analyzed for this study. None of the Hadean zircons found to date display a spongy texture indicative of fluid-dominated recrystallization. In Phanerozoic zircon, a Th/U ratio <0.1 serves as an indicator for metamorphic zircon (22). In the GSB zircons, Th/U ratios vary from 0.18 to 1.15, supporting a primary igneous origin. Similarly, GSB Hadean zircons show chondrite-normalized REE patterns with light REE (LREE) depletion, heavy REE (HREE) enrichment, a positive Ce anomaly, and a negative Eu anomaly (Fig. 1), consistent with an igneous source (23).

Fig. 1.

Chondrite-normalized REE abundance of Hadean zircons from the GSB. (A) REE patterns of Hadean Group II show depletion in MREE relative to Group I. (B) Average model melt composition derived using Ti-calibrated Kds (17) compared to known Paleoarchean felsic igneous rocks in the Barberton greenstone belt (74–76). Group I Hadean zircons show similar model melt compositions to rhyolite of the 3.55 Ga Theespruit and rhyodacite of the 3.25 Ga Bien Venue Formations; Group II shows a similarly low HREE abundance to the 3.45 Ga Hooggenoeg dacite and the 3.23 Ga Kaap Valley Tonalite. LREEs were not evaluated because their low abundances and the potential influence of minute inclusions makes the LREEs inherently unreliable (16). (C) Representative CL images of zircons from Group I and Group II.

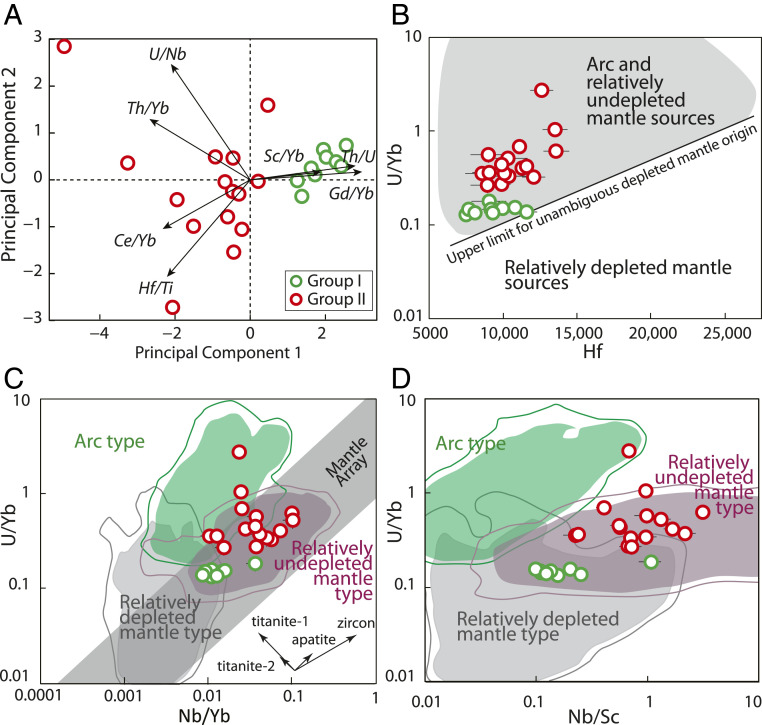

To evaluate the compositions and compositional variability among GSB zircons, it is important to focus on element ratios for comparisons between the zircons, rather than absolute abundances, to minimize the effect of the melt temperature on mineral partition coefficients (Kds) (16). Previous studies have shown that cation ratios including U, Th, Nb, Sc, Ce, and Yb provide the most compositional distinction among zircons from different tectono-magmatic settings (16). To understand compositional differences between the zircons, we performed a simple principal component analysis (PCA) using trace element ratios and plotted bivariate diagrams (Fig. 2). The results of the PCA show a clear correlation between Sc/Yb, Th/U, and Gd/Yb values. In turn, these values show a moderate negative correlation to the other ratios, U/Nb, Th/Yb, Ce/Yb, and Hf/Ti. In general, U/Yb directly correlates with Th/Yb, and the majority of zircons fall on broad trends of increasing U/Yb with increasing Nb/Yb and Nb/Sc and decreasing Sc/Yb and Gd/Yb. While there are several general trends between many trace element proxies, there is no coherent trend between age and geochemical proxies (e.g., U/Yb), as would be expected if the zircons formed by simple fractionation from a single magma composition (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

(A) PCA in zircon trace element ratios. Principal component 1 accounts for 51.1% and principal component 2 for 16.1% of the variability. (B and C) Zircon trace element plots modified after Grimes et al. (16). (B) U/Yb ratio versus Hf for zircons from the GSB. (C) U/Yb versus Nb/Yb plot with inset showing the effect of open-system (Rayleigh) fractionation of select minerals on the displayed system (16). (D) U/Yb versus Nb/Sc plot. Colored fields represent a global compilation of zircons from different Phanerozoic tectono-magmatic settings. The outer contour line is shown at the 95% level, which represents the amount of the distribution inside the contour. Green circles represent Group I zircons; red circles represent Group II.

Besides these general characteristics, there is an apparent clustering in the data. The U/Yb data show a separation of the zircon compositions into two groups (here termed as Group I and Group II) that, based on a PCA and bivariate plots, also translates to general differences in other trace element ratios (Figs. 2 and 3 and Dataset S3). It is important to note that due to the low number of zircons, it is difficult to evaluate if these groups represent distinct source magmas or what is actually a continuum of compositions. However, discussing these as separate compositional types of zircons makes it easier to compare and contrast the different possible processes or sources that could produce the observed variations. Zircons of Group I (5 zircons with 11 analyses) shows less spread in its compositional averages with lower U/Yb (0.15 ± 0.015), higher Th/U (0.91 ± 0.16), higher Gd/Yb (0.09 ± 0.01), lower Nb/Yb (0.01 ± 0.01), lower Nb/Sc (0.29 ± 0.06), higher Ti (8.6 ± 3.3 ppm), and elevated Sc/Yb (0.08 ± 0.04). In contrast, Group II (10 zircons with 16 analyses) shows a wider spread with elevated U/Yb (0.61 ± 0.61), lower Th/U (0.54 ± 0.21), lower Gd/Yb (0.05 ± 0.02), lower Ti (5.1 ± 3.8 ppm), higher Nb/Yb (0.04 ± 0.04), higher Nb/Sc (1.0 ± 0.02), and lower Sc/Yb (0.05 ± 0.02). There is some variability in the geochemical composition between different spots on the same grain. This is typical for igneous zircon and reflects the expected changes in the melt composition driven by melt fractionation and changing zircon partition coefficients during zircon growth (14, 15). However, all analyses on the same grain fall into the same group. This shows that, while there were the expected compositional variations during individual zircon growth, the general compositional differences between the two groups remain.

Fig. 3.

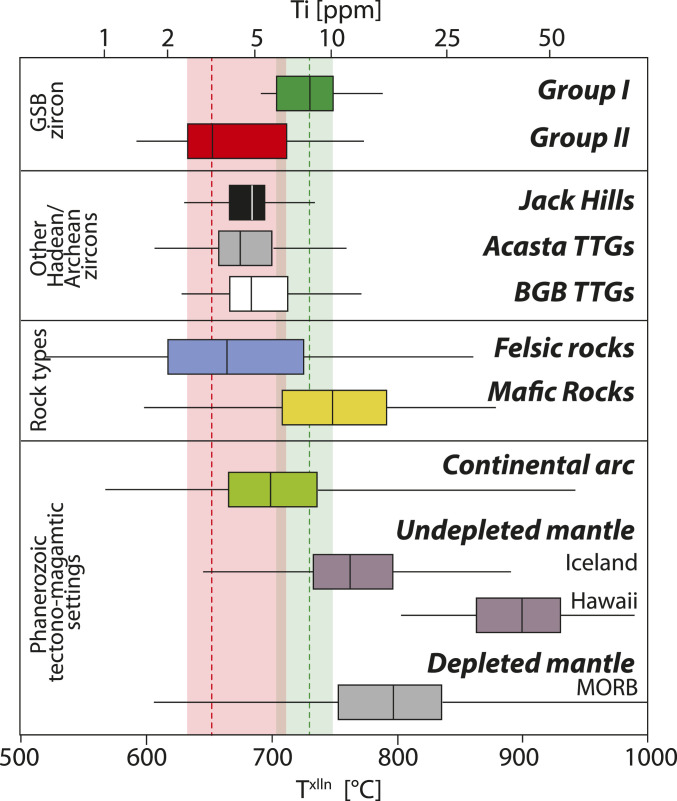

Ti (ppm) and Txlln box-and-whisker plots (the ends of the boxes are the upper and lower quartiles, vertical lines mark the median, and horizontal lines extend to the highest and lowest observations) of Hadean zircons of the GSB in comparison to those of zircons derived from the Jack Hills (37), TTGs of the Acasta Gneiss Complex (36), TTGs of the Barberton greenstone belt, mafic and felsic rocks (35), and different tectono-magmatic environments in the Phanerozoic (16). All temperatures were calculated with αSiO2 and αTiO2 of 1.

The Ti abundance in zircon can be used to calculate the temperature of the melt at which the zircon crystallized (Txlln) (24). However, this calculation requires knowledge of the αSiO2 and αTiO2 of the parental magma. The absence of a petrologic context and of identifiable mineral inclusions on the polished surfaces of the Hadean GSB zircons means that it is currently not possible to directly constrain αTiO2 and αSiO2. While the presence of quartz can generally be assumed (i.e., αSiO2 is usually close to unity), αTiO2 is variable but generally >0.6 for igneous systems (25, 26). For Txlln calculations, we used an αTiO2 and αSiO2 of 1, which assumes the coexistence of zircon with quartz and rutile in the melt. These temperatures represent a minimum estimate unless co-crystallization with rutile can be established, leading to the possibility that temperatures are underestimated by up to 50 °C (24). For consistency, we calculated Txlln for zircons from different environments and locations using the same assumptions (Fig. 3). Although the calculation of absolute temperatures is not possible, a comparison under similar assumptions remains meaningful, particularly in the case of the rare Hadean zircons. The two groups show some overlap. Group I zircons have an average Ti value of 8.6 ± 3.3 parts per million (ppm), reflecting a Txlln of 723 ± 44 °C (Fig. 3). In contrast, Group II, while showing a wider spread in temperatures, has a comparatively lower average Ti value of 5.1 ± 3.8 ppm, reflecting a Txlln of 668 ± 57 °C.

Compositional Variability and Possible Petrogenetic Implications

The trace element compositions of the two zircon groups show certain differences that reflect the different natures of the parental magmas (Fig. 2). This is exemplified in the U–Nb systematics. The relationship between U/Yb and Nb/Yb in zircon from modern magmatic systems is influenced by variations in mantle source composition (as today between modern mid-oceanic ridge and plume magmas), aqueous fluid input (as today in arc magmatism), and crustal assimilation (16). In general, with increasing fractionation of a melt, the U/Yb and Nb/Yb ratios will increase as a reflection of increasing fractionation of zircon, apatite, and garnet out of the magma (Fig. 2). Consequently, U/Yb and Nb/Yb values in zircon increase with increasing melt crystallization, and more evolved parental melts in general tend to have zircons with higher values. Group I and many of Group II zircons define a positive trend between U/Yb and Nb/Yb—that is, parallel to the vector characterizing the fractional crystallization of zircon and apatite. That trend parallels today’s zircon mantle array, which was based on a qualitative survey of zircon derived from mid-oceanic ridges and oceanic islands (16). Hence, this positive correlation may be related to differences in the original source compositions of the parental melts and/or relative melt evolution (Fig. 2C).

Zircons of Group I show lower U/Yb and Nb/Yb ratios and less spread in values compared to those of Group II (Fig. 2C). Thus, the elevated values indicate relatively more evolved melts for Group II compared to Group I as well as more spread, which we interpret to reflect some degree of heterogeneity of the crustal sources of melts with otherwise generally similar characteristics. A few zircons of Group II fall off this trend toward higher U/Yb and relatively lower Nb/Yb values relative to mantle-derived zircon. In general, a U/Nb >40 indicates a clear hydrous melting signature caused by flux melting in modern arc settings (16). However, a U/Nb value of >40 is only reached in one of the zircons (with two analyses), and the other zircons show values predominantly in agreement with a nonarc, mantle origin.

Sc in zircon also tracks mineral fractionation behavior and can detect flux melting (16). Sc in zircon can track the Sc depletion of the melt during open-system fractionation of ferromagnesian minerals involving amphibole and/or clinopyroxene, driving the Sc/Yb value down (16, 27, 28). In general, with increasing fractionation of a melt during cooling, Sc and Sc/Yb in zircon decrease while U/Yb and Hf increase (16, 28). Overall, Group II zircons show lower Sc/Yb values (average of 0.05 ± 0.02) at lower Txlln and higher U/Yb values compared to Group I zircons (average 0.08 ± 0.04), suggesting that Group II zircons experienced a higher degree of fractionation. Furthermore, a lower degree of fractionation is necessary to reach zircon saturation under hydrous melting conditions in continental arc magmas, and, hence, no extensive basalt fractionation occurs prior to zircon fractionation (16). As a consequence, Sc/Yb values are clearly elevated (generally >0.1) in environments that experienced flux melting compared to mantle environments dominated by basaltic melts where extensive fractionation needs to occur prior to zircon crystallization (16). The low Sc/Yb together with the low U/Nb values of Hadean zircons suggest that flux melting was not a major process in the GSB source.

The differences seen between Group I and Group II zircons are furthermore corroborated by their REE geochemistry. Group II zircons show a depletion in the middle REE (MREE) (i.e., lower Gd/Yb) compared to Group I (Figs. 1A and 4B). The observed general trend of decreasing Gd/Yb together with increasing U/Yb is typical for fractionation trends caused by crystallization of minerals that sequester MREE over HREE (e.g., amphibole, titanite, ilmenite, monazite, and apatite) conjointly with the decreasing temperature’s effect on the Kds (16, 29). To eliminate the effect of temperature on the REE, we used Ti-calibrated Kds (17) to estimate the compositions of the melts that would have been in equilibrium with the zircons. (Fig. 1B). Preliminary testing has shown that these Kds are sufficiently robust to differentiate different crustal settings (30). Model melt for zircons of Group I show about half an order of magnitude enrichment in the REE compared to those of Group II as well as higher Y abundances. Higher temperature and lower pressure melts tend to contain minerals (olivine, pyroxenes, feldspar, mostly plagioclase, and oxides ± quartz, unless clinopyroxene is unusually abundant) in which REEs and Y are incompatible. As a consequence, fractionated melt pockets from such melts will crystallize zircon with high MREE and Y abundances (16, 29). A similar trend is seen in model melt calculations of zircon derived from highly fractionated pockets in low-H2O and low-pressure modern oceanic settings, such as plagiogranites in mid-oceanic ridge environments. These tend to have higher HREE contents and shallower MREE-HREE slopes than those in continental settings and tonalite-trondhjemite-granodiorite (TTGs) (30). Model melt calculations of Group II zircons show depletion in the chondrite-normalized HREE (below 10), possibly indicating crystallization in the presence of garnet ± amphibole. Although the average model melt composition does not show the characteristic steep pattern, the HREE depletion resembles that of Archean TTGs around the globe and in the Barberton greenstone belt area itself (31), whose HREE depletion is commonly interpreted to reflect dehydration melting with garnet in the residue (or, equivalently, hydrous fractional crystallization with garnet in the cumulate) at pressures higher than 10 to 15 kilobars (32, 33). Hence, Group II zircons may have formed at deep crustal levels, but alternative shallower melting scenarios that allowed for the presence of garnet are also possible (34). In contrast, model melt calculations for Group I zircons essentially lack depletion in the HREE, suggesting an origin at shallower depths and lower pressures (i.e., lower than 10 to 15 kilobars).

Fig. 4.

Geochemical comparison between Jack Hills (3, 37, 38) (gray dots) and GSB Hadean zircons. (A) U/Yb versus Hf, (B) U/Yb versus Gd/Yb, (C) U/Yb versus Nb/Yb, and (D) Th/U versus Ti (ppm). Fields for Phanerozoic zircons are from Grimes et al. (16).

Finally, the presence of a perhaps more juvenile and a more evolved source component is supported by the Ti and hence the Txlln. In general, Txlln of zircon decreases from mafic to felsic rocks (35), but exact temperatures vary between tectonic environments as a function of magma composition and crystallization pressure. The higher Txlln for Group I zircons (723 ± 44 °C) shows greater overlap with zircon formed in highly fractionated pods in mafic rocks (758 ± 56 °C) than with felsic source rocks (Fig. 3) (35). In contrast, the low Txlln in Group II zircons (668 ± 57 °C) are similar to what is typically observed within zircon from Phanerozoic felsic rocks (average: 670 ± 82 °C) (35) and Archean TTGs (average: 678 ± 40 °C) (36), although there are some examples of zircon from mafic melts reaching Ti abundances as low as seen in Group II (35).

In summary, the geochemical signatures of the two groups of GSB Hadean zircons record crustal heterogeneity likely related to an origin from two different sets of parental magma compositions: Group I zircons show evidence for crystallization of a relatively more primitive magma at low pressure and elevated temperatures, while the majority of Group II zircon compositions are consistent with crystallization from a cooler, more evolved source magma of TTG-like composition that possibly assimilated a small amount of hydrated crust.

Comparison to Hadean Zircons of the Jack Hills

The geochemistry of Hadean Jack Hills zircons (37, 38) and the GSB zircons are similar, especially for the Group II zircons. (Fig. 4). Jack Hills zircons are statistically indistinguishable from Group II zircons in terms of U/Yb, Nb/Yb, U/Nb, Gd/Yb, Eu/Eu*, U, Y, Hf, and Ti based on the Welch’s t test. Furthermore, Sc values are similarly low in both sections. Sc values for the Jack Hills have only been reported by Maas et al. (39). They report Sc abundances of which half are below detection limit (<17 ppm) or, for the remaining grains, averaging 35 ppm. This is consistent with the Hadean zircons from the GSB, which are all <54 ppm (averaging 17.4 ppm).

Similar to the GSB zircons of Group II, the geochemistry of the Jack Hills zircons has been interpreted to reflect a source of the parental melt relatively undepleted in incompatible elements that possibly experienced some wet melting based on high U/Yb values, relative MREE depletion, and low Ti values (29). Similar to the GSB, many of the Jack Hills zircons plot on the mantle array in the U/Yb versus Nb/Yb diagram and may have been derived by remelting of a mafic, mantle-derived crust. However, while the GSB has only two analyses on one zircon that plot above the mantle array and show a clear arc-like flux melting signature with U/Nb >40, for the Jack Hills, about 50% of zircons are slightly elevated above the mantle array, and three Jack Hills zircons display a clear arc-like hydrous melting signature. The presence of some Nb-depleted zircons (Fig. 4C) together with mildly elevated δ18O of 6.3 to 7.5‰ (2, 38, 40–43) suggests that the mantle-derived mafic crust experienced some subsequent reworking that included crust that had interacted with water at low temperatures (44). Lastly, recent studies have suggested that Jack Hills Hadean zircons may have been derived from TTG-like crust based on model melt calculations (30) and similarities in their low Ti abundances and elevated U/Yb values to Paleoarchean TTGs of the Acasta Gneiss Complex (36). These similarities suggest that zircons from Group II in the GSB and those of the Jack Hills were derived from more evolved magmas that had rather similar compositions at zircon saturation.

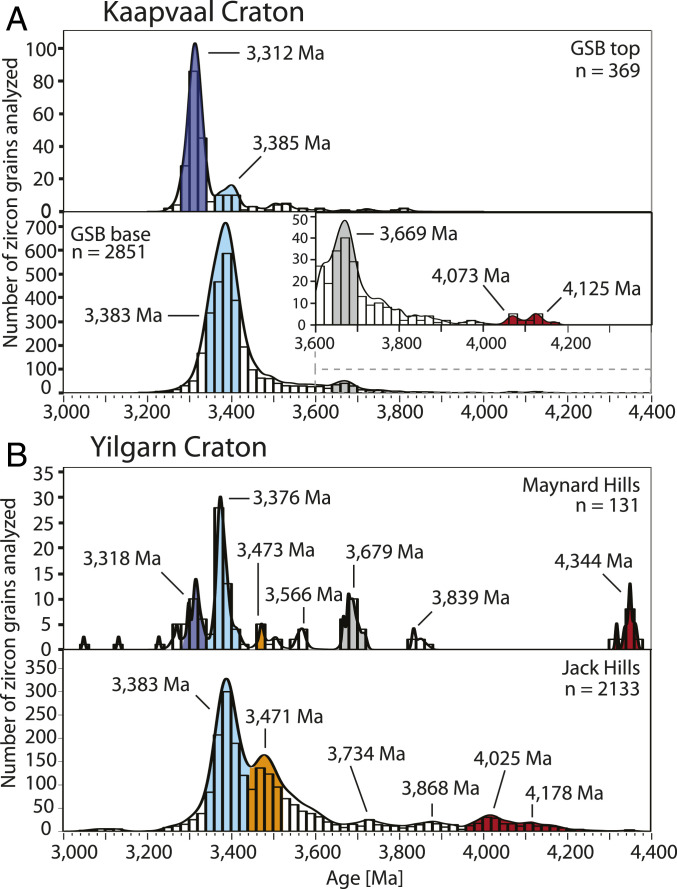

Intriguingly, Byerly et al. (10) noted similarities between the zircon ages of the GSB and the Jack Hills. Both sequences reveal a major detrital age peak at 3.38 Ga, a broad range of zircon ages between 3.38 Ga to 3.90 Ga, and a minor cluster of late Hadean zircons (Fig. 5). Accessory peaks, however, appear to be unique to each of the locations. The GSB contains peaks at 3.65 Ga and 3.31 Ga that are absent in the Jack Hills but lacks the 3.47 Ga age peak found in the Jack Hills. Another area with reported Hadean zircons in the Yilgarn Craton that is thought to have had the same crustal source as the Jack Hills is the Maynard Hills greenstone belt (45–47), ∼300 km southeast of the Jack Hills. Its zircon distribution displays the entire range of zircon age clusters and could represent a link between the two sequences. The zircon age distribution seen in these three sequences is not common in other Archean sequences (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Hence, it does not appear to represent a global zirconforming and -preserving event such as major peaks in global zircon compilations seen during Phanerozoic supercontinent formation (48).

Fig. 5.

Probability density plots of detrital zircons from (A) the base and the top of the GSB in the Kaapvaal Craton and (B) the Maynard Hills greenstone belt (47), and a representative set of detrital zircon dates from the Jack Hills area (77) in the Yilgarn Craton. Prominent age clusters (colored) were calculated using weighted mean ages and overlap within 2 σ-level.

Lastly, the GSB provenance suggests that they may have been sourced from crust outside the Barberton greenstone belt. The zircon age clusters seen in the GSB are not found as either auto- or xenocrysts in felsic igneous rocks (49) nor as detrital zircon in sedimentary units within the greenstone belt (11). Additionally, the dominant Cr-spinel population from the GSB does not overlap in its geochemistry with those of associated komatiitic flow sequences analyzed to date (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) (50). These results suggest that at least the zircon and spinel components of the GSB may not have been derived from the immediate vicinity of the greenstone belt but possibly from relatively distant source rocks, perhaps a source that was also linked to the Yilgarn Craton.

The results show that not only was the nature of source rocks for the Hadean zircons of Group II similar to those of the Jack Hills but also the similarities in zircon age peaks offer the prospect of a common source. It is possible that an ancient crustal terrane existed in the Hadean and contributed sediments to the Jack Hills, Maynard Hills, and GSB areas with different detritus being added during their transport. Nonetheless, the similarities in geochemistry and detrital zircon age peaks may be coincidental, and the lower abundance of Hadean zircons in the GSB and the absence of Group I-type Hadean zircons in the Jack Hills mark clear differences between the two sequences. Additional geochemical and isotopic characterization of the zircons is clearly necessary for an unequivocal correlation.

Comparison to Zircons from Phanerozoic Crustal Settings

Grimes et al. (16) proposed a series of trace element discrimination diagrams to distinguish zircons derived from different modern tectono-magmatic settings. These can be used to examine the possible sources of Hadean zircons from the GSB. While the exact nature of crustal processes during the Hadean is still controversial, it is possible that several different magmatic sources and crustal settings somewhat akin to modern crustal settings may have existed in the Hadean. Besides “primordial” crust (i.e., mafic crust derived from a relatively undepleted mantle), some form of more evolved felsic, perhaps continental crust, may have been present (51, 52). For example, the isotopic and geochemical characteristics of zircons from the Jack Hills have been interpreted to represent continental crust by some researchers (25, 38, 39, 43). If felsic and/or mafic crust was being removed and not remixed with the mantle during the Hadean, a complementary depleted mantle may have also existed. Thus, a comparison of the Hadean zircon geochemistry to that of Phanerozoic zircon from different tectono-magmatic settings can highlight possible similarities and differences in the nature of melt sources.

Although trace element abundances likely varied through time because of the secular cooling of the mantle (53), the use of some trace element ratios as proposed by Grimes et al. (16) reduces the temperature effect. A global database of 52,300 whole-rock samples with both major and trace element data, weighted by how much zircon each rock saturates, shows that continental crust ∼4 Ga ago likely had U/Yb, Nb/Yb, and Nb/Sc ratios that vary by less than a factor of two from those in the Phanerozoic (SI Appendix, Fig. S6) (54). If this global database is sufficiently representative of preserved continental crust through time, then secular cooling of the mantle has not greatly influenced the relevant trace element ratios of zircon at the scale of the Grimes discrimination plots (16), and the locations of tectono-magmatic fields in log-ratio space are still applicable. One advantage of the direct use of zircon trace elements for comparison to tectono-magmatic settings is that it minimizes reported issues with model melt calculations for Paleoarchean rocks (36). The direct approach is especially pertinent for detrital zircons which may have originated from a range of different rock types, each individual zircon potentially requiring different Kds.

Overall, the comparison between the Hadean GSB zircons and those from modern tectono-magmatic setting shows that all of Group I zircons and a large number of Group II zircons fall into the field that represents a relatively undepleted mantle source signature that is exemplified today by zircons from ocean islands like Iceland and Hawaii, rather than into fields for depleted mid-oceanic ridge or arc environments (Fig. 2). In contrast, only two analyses on one Hadean GSB grain clearly fall into the field of magmatic arc associations as delineated by Grimes et al. (16).

As seen in Fig. 2, Group I zircons plot in the lower end of the field for relatively undepleted mantle zircon signatures using the U/Yb, Nb/Yb, and Nb/Sc criteria. While Group I zircons display uniquely low U/Yb ratios that have not been previously reported in Hadean zircons (Figs. 2C and 4), the GSB Hadean zircons have U/Yb = 0.15 and Nb/Yb = 0.014 values that are significantly different to those of zircon derived directly from Phanerozoic depleted mantle represented by today’s mid-oceanic ridge environments (U/Yb <0.1 and Nb/Yb <0.005) (Fig. 2) (16). Therefore, these Hadean zircons were derived from magmas that were not as depleted as most zircon from modern mid-oceanic ridges but instead were more enriched and similar to modern zircon found on Iceland and Hawaii. Yet, it is notable that Group I zircons overlap only with the lower end of the Ti spectrum of zircon from plume sources (Fig. 3). Because most GSB zircons do not show an obvious Nb depletion and U/Yb enrichment that would indicate that slab-derived fluids promoted zircon formation at lower temperatures, it is possible that the zircons formed late in the crystallization sequence of relatively dry magmas and, thus, under slightly lower temperatures compared to modern environments. One possible explanation for the relatively low temperatures is that secular trends in average magma zirconium content and magma polymerization state caused delayed Zr saturation in magmas during early Earth history (53). In general, decreasing bulk [Zr] by 30 ppm will lower the onset of crystallization by 11 °C, all other conditions being equal (26). This caused an onset of zircon crystallization on average at lower temperatures during early Earth history (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7). Based on zircon saturation modeling of 52,300 continental whole-rock analyses (53, 54), the average calculated zircon crystallization temperature (normalized to 6 kilobar and 3 weight % H2O) was 34 °C lower in the Paleoarchean (804 ± 1 °C), and likely even lower in the Hadean, compared to today (838 ± 1 °C) (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7). While we cannot constrain the exact Zr abundance of the parental crustal rocks from which the GSB zircons were derived, lower apparent Txlln (i.e., Ti values) may at least in part be explained by a delay in zircon saturation in low-Zr magmas early in Earth history.

Group II zircons share most characteristics with Phanerozoic undepleted mantle; however, some show similarities to arc-derived continental crust. Today, continental crust is shaped by a complex series of tectonic processes, including arc magmatism, terrane accretion, crustal reworking, and late-stage formation of potassic granitic plutons (55). As a consequence, the hallmarks of zircon derived from Phanerozoic continental arcs include relative depletion in Nb, low Ti content, and enrichment in Sc (16). Low zircon Ti abundances (and hence, low Txlln) in arcs today are related to hydrous melting conditions (25). Txlln values of many Group II zircons, even when adjusted for a delay in zircon saturation, are lower than what is typically seen in zircon from modern, relatively undepleted mantle sources and may similarly be related to hydrous conditions. However, Phanerozoic arc-like Nb depletion occurred in only one of the zircons. Zircon formed in modern ambient mantle environments (mid-oceanic ridge or ocean island settings) typically has U/Nb values <20, whereas arc-related and continental-crust–derived zircon usually has U/Nb >40 (16). Similar to a dry mantle environment, the vast majority of GSB zircons show a U/Nb value of <40 (average of all GSB zircons is 17.2), and only two analyses on the same grain show values above 40. Furthermore, the Hadean zircons from the GSB lack the characteristic high Sc and Sc/Yb values of continental arcs. Combining the two proxies, the U/Yb versus Nb/Sc diagram (Fig. 2D) shows the strong similarity of the GSB zircons to those from modern undepleted mantle environments and only a single analysis falls into the continental arc field (Fig. 2D). Overall, while some assimilation of hydrated crust appears to have occurred, the lack of strong Nb depletion and Sc enrichment makes an original source of ambient mantle composition compelling and an origin from flux melting, such as that seen in a continental arc setting, unlikely.

An origin from remelting of ambient mantle-derived sources also appears possible for some of the Jack Hills zircons. While Carley et al. (29) pointed out notable differences in the composition of the Hadean Jack Hills zircons to those from plume-derived magmas on Iceland and favored a continental arc origin, they did not evaluate the parameters Grimes et al. (16) later found to be particularly crucial in differentiating continental arc from relatively undepleted mantle settings: relative Nb depletion and Sc enrichment. Most published Jack Hills Nb data (3, 38) do not display as extreme an Nb depletion as most modern arc zircon, and a majority fall into the transitional area where the continental arc and relatively undepleted mantle fields overlap (U/Nb 20 to 40); hence, either origin may be possible (Fig. 4). In addition, while Maas et al. (39) associate the reportedly low Sc in Jack Hills zircon with growth in an Sc-poor continental environment, Grimes et al. (16) later showed that Sc and Sc/Yb values are elevated in continental arc rocks compared to those derived from mid-oceanic ridge or ocean island settings. Finally, the delay in zircon saturation during the Hadean due to the higher heat flux from the mantle may account for some, though certainly not the majority, of the low Ti zircons from the Jack Hills (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7), and assimilation of hydrated crust appears to have occurred here too. Hence, some Jack Hills zircons, similar to at least one Group II GSB zircon, appear to clearly display an arc affinity based on the relative Nb depletion and are possibly supported by the presence of primary muscovite inclusions in some zircons indicating peraluminous protoliths (56, 57). Yet, an overall match of the zircon geochemical signature with continental arc must be tentative, and a contribution of some zircons derived from crustal rocks with mantle affinity, similar to the majority of GSB zircons, should be considered.

In light of these results, some general statements can be made when comparing the geochemistry of the Hadean GSB zircons to those formed in Phanerozoic source environments: 1) Ti concentrations in Hadean zircons may be ∼35 °C lower due to the higher heat flow from the mantle and its effect on zircon saturation (54, 58). While this change translates to a similarity of Group I zircons to those formed in modern relatively undepleted mantle settings, the Group II zircon’s adjusted Txlln is still lower than in modern mantle-related settings and likely requires some reworking of hydrated crust to form zircons at such low temperatures. 2) The compositional features of the GSB zircons may be explained by varied melting processes acting on perhaps more mafic, ocean-type crust that was itself derived by the melting of sources with a mantle affinity for the majority of GSB zircons. Although relatively undepleted mantle sources are associated with deep plume (e.g., Iceland or Hawaii) and rift environments in modern tectonics, those tectonic environments are not implied for the Hadean, as the mantle structure was likely different. The GSB zircon compositions form an array within and parallel to the modern mantle Nb/Yb versus U/Yb array, and only a few of the GSB analyses indicate some form of arc-like wet melting. However, it is important to emphasize that the weak to moderate Nb-depletion does not provide conclusive evidence for some, perhaps less efficient, subduction processes already operating in the Hadean, as these data could perhaps be explained by the burial of hydrated crust through volcanic resurfacing or sagduction (5, 6). The results only suggest that some process that at least mimics fluid-assisted melting occurred at that time. 3) Lastly, it is critical to emphasize that even adjusting for the changing nature of the crust through time, none of the geochemical proxies used here require an origin of the Hadean GSB zircons from fully formed Phanerozoic-style arc magmas. While at least some of the GSB zircons were apparently derived from felsic, TTG-series rocks, the absence of major Nb depletion and Sc enrichment suggests that these zircons do not necessitate an origin from fully formed Phanerozoic-style continental arcs.

Implications

The present study using trace elements and REE of Hadean zircons from the GSB suggests that the majority of zircons formed by the melting of mafic crust derived from the ambient mantle and neither the mantle melting nor melting of the mafic crust involved modern arc magmatic processes. More specifically, the U-Nb-Sc-Yb systematics of the GSB zircons suggest a relatively undepleted mantle origin as seen in modern plume-related settings. The Hadean zircons’ geochemical compositions suggest derivation from at least two types of melt: more mafic, moderate temperature melts and somewhat more evolved and lower temperature melts. Because only a single GSB zircon clearly suggests an arc-like flux melting signature, it is unlikely that the GSB zircons reflect an origin from or associated with a modern-style continental arc. Instead, because the GSB zircons show a wide range in ages, exhibit diverse geochemical features, and lack the coherence expected for a fractionation sequence, they are perhaps best interpreted as having protoliths derived from an ambient mantle, and this mantle-derived crust, subsequently, experienced reworking in the presence of some amount of water or was a hydrated crust. Overall, although these zircons can only reveal information about their specific sources, our results may suggest that more mafic, relatively undepleted mantle-derived melts played an important role during crust formation in the Hadean.

In addition, the GSB Hadean zircons also suggest a more important role for a previously poorly represented, unrecognized compositional component in the Hadean crust that can produce higher Ti (8 to 16 ppm) and low U/Yb zircons. Based on trace element studies, the Jack Hills zircons and the few other Hadean zircons that have been studied in detail are dominated by lower temperature undepleted crustal sources (8, 59–62). This apparent homogeneity in the inferred source(s) of non-GSB zircons may be related to a bias in the zircon record because silica-rich, differentiated magmas are the most zircon fertile and will crystallize substantially more zircon than more mafic magmas. To date, only a single Hadean zircon from the Cathaysia Block from southern China (8) has been reliably shown to have Ti abundances of 53 ± 3 ppm in its core, suggesting a Txlln of 910 °C. Xing et al. (8) interpret the zircon to have been derived from granitoids that formed under hot and dry melting conditions. This single high-temperature zircon together with Group I moderate-temperature GSB zircons suggest that there was a greater diversity of Hadean crustal sources than previously recognized and that such zircons, if found more widely, offer the potential to better characterize crustal compositions and magmatic processes in the Hadean.

Materials and Methods

Samples were obtained from the GSB-type locality (S25°54′33.11″ and E31° 2′42.35″) and a second location (S25°53′56.50″ and E31° 2′2.13″). Zircon grains were extracted from 6- to 30-kg sandstone samples using standard size, hydrodynamic, and density mineral separation techniques at Stanford University. The samples were crushed in a jaw crusher into rock chips and then ground in a disk grinder to medium-grained sand size. Light and heavy mineral fractions were separated utilizing a Gemini table, and, subsequently, the magnetic minerals were removed from the heavy fraction utilizing a Frantz isodynamic magnetic separator. The residual minerals were split using methylene iodide to remove any remaining minerals less dense than 3.32 g/cm3. Zircons were mounted onto 1″ epoxy mounts together with Sri Lanka (563.5 ± 2.3 Ma), FC-1 (1099.0 ± 0.6 Ma), R33 (419.3 ± 0.4 Ma), and OG1 (3465.4 ± 0.6 Ma) standards and then polished.

Initial age dating was done by Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry with a 15-μm spot diameter at the Arizona LaserChron Center using established techniques (63, 64) (Dataset S1). Grains with 204Pb >600 counts, low 206Pb/204Pb and poor precision, and, unless Hadean in age, concordance below 95% were excluded. For Hadean zircon, a cutoff of 80% was used.

Subsequently, we analyzed the Hadean grains with the sensitive high-resolution ion microprobe reverse geometry (SHRIMP-RG) at Stanford University to confirm the 207Pb/206Pb ages (Dataset S2) and to measure the trace element geochemistry [the same instrument was used by Grimes et al. (16)] (Dataset S3). Each grain was analyzed in up to three spots depending on available space. Zircon U-Pb dating was conducted following the methods of Premo et al. (65). AS3, MAD, and OG1 were run as standards. Data reduction was accomplished using SQUID and Isoplot (66). Ages are calculated using 204Pb-corrected 207Pb/206Pb ratios and 204Pb-corrected 206Pb/238U and 207Pb/235U Concordia model ages. Major, trace, and REE geochemistry data were calibrated to primary standard MAD-599 (67) and secondary standard 91500 (68), following the procedure described by Grimes et al. (16).

The geochemical signal can be biased by chemical alteration, especially in radiation-damaged zones. The beam was focused on sites with no obvious impurities and within the same crystallographic domain where the grain was dated. Rims, either resulting from magmatic overgrowth or solid-state recrystallization, were not analyzed. We excluded analyses where the analytical pits revealed inclusions or cracks during later microscopic imaging. Furthermore, geochemical screening was applied to filter analyses that show elemental enrichments of nonconstituent cations and thus signify contamination. Ca and P serve as screens for apatite inclusions, and we excluded zircons with high Ca (>50 ppm) and high P abundances (>1,000 ppm). Similarly, cracks commonly contain iron and titanium oxides (69), and thus we excluded analyses with elevated Fe (>100 ppm). Grains with high Al abundance (>100 ppm) were excluded as well, as they signify zones where zircon has been amorphized. Finally, we applied the LREE index to identify altered zircon grains (37). In total, 27 geochemical analyses on 15 Hadean zircons pass all filters and likely represent primary geochemistry. A total of 12 analyses on 8 zircons did not pass these filters. Subsequently, we conducted a PCA using the factoextra R package written by Alboukadel Kassambara and Fabian Mundt. For a more complete discussion of PCAs, see Wackernagel (70).

Variations in relevant geochemical ratios in magmas likely to saturate zircon were conducted using the dataset and bootstrap resampling approach of Keller and Schoene (54) and weighted by the calculated mass of zircon saturated according to the methods of Keller et al. (53), normalized to 6 kilobars and 3 weight %. H2O. In this approach, the composition of the interstitial melt of a crystallizing igneous whole-rock sample is calculated throughout the entire crystallization process using alphaMELTS (71, 72) and zircon saturation state assessed using the zircon saturation calibration of Boehnke et al. (73).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sappi and the Mpumalanga Tourism and Parks Agency for access to lands. Funding for travel expenses and analytical costs were kindly provided by the School of Earth, Energy, and Environmental Sciences. N.D. was supported through the Liebermann Fellowship. We also thank Emily Stoll, Anton Drabon, William Thompson-Butler, and Jake Harrington for help during sampling. The staff of the Arizona LaserChron Center at the University of Arizona and Matthew Coble at the SHRIMP-RG laboratory at Stanford University were very helpful during detrital zircon analyses. Ruth Dawn and David Damby at the US Geological Survey in Menlo Park helped take Cathodoluminescence images. This paper benefited from discussions with Marty Grove. We gratefully acknowledge editor Albrecht Hofmann and three reviewers who provided many helpful suggestions and thoughtful insights.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

4Retired author.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2004370118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

References

- 1.Armstrong R. L., Harmon R. S., Radiogenic isotopes: The case for crustal recycling on a near-steady-state no-continental-growth Earth [and Discussion]. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 301, 443–472 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison T. M., Schmitt A. K., McCulloch M. T., Lovera O. M., Early (≥ 4.5 Ga) formation of terrestrial crust: Lu-Hf, δ18O, and Ti thermometry results for hadean zircons. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 268, 476–486 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner S., Wilde S., Wörner G., Schaefer B., Lai Y. J., An andesitic source for Jack Hills zircon supports onset of plate tectonics in the Hadean. Nat. Commun. 11, 1241 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamber B. S., The Enigma of the Terrestrial Protocrust: Evidence for its Former Existence and the Importance of its Complete Disappearance (Dev. Precambrian Geol, 2007), chap. 2.4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer A. B., et al., Hafnium isotopes in zircons document the gradual onset of mobile-lid tectonics. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 14, 1–6 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kemp A. I. S., et al., Hadean crustal evolution revisited: New constraints from Pb-Hf isotope systematics of the Jack Hills zircons. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 296, 45–56 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhuime B., Hawkesworth C. J., Cawood P. A., Storey C. D., A change in the geodynamics of continental growth 3 billion years ago. Science 335, 1334–1336 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xing G. F., et al., Diversity in early crustal evolution: 4100 Ma zircons in the Cathaysia block of southern China. Sci. Rep. 4, 5143 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhuri T., Wan Y., Mazumder R., Ma M., Liu D., Evidence of enriched, hadean mantle reservoir from 4.2-4.0 Ga zircon xenocrysts from paleoarchean TTGs of the Singhbhum Craton, Eastern India. Sci. Rep. 8, 7069 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byerly B. L., et al., Hadean zircon from a 3.3 Ga sandstone, Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa. Geology 46, 967–970 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drabon N., Lowe D. R., Byerly G. R., Harrington J. A., Detrital zircon geochronology of sandstones of the 3.6-3.2 Ga Barberton greenstone belt: No evidence for older continental crust. Geology 45, 803–806 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie X., Byerly G. R., Ferrell R. E. Jr, IIb trioctahedral chlorite from the Barberton greenstone belt: Crystal structure and rock composition constraints with implications to geothermometry. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 126, 275–291 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tice M. M., Bostick B. C., Lowe D. R., Thermal history of the 3.5–3.2 Ga Onverwacht and fig tree groups, Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa, inferred by Raman microspectroscopy of carbonaceous material. Geology 32, 37 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belousova E. A., Griffin W. L., O’Reilly S. Y., Fisher N. I., Igneous zircon: Trace element composition as an indicator of source rock type. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 143, 602–622 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimes C. B., et al., Trace element chemistry of zircons from oceanic crust: A method for distinguishing detrital zircon provenance. Geology 35, 643–646 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimes C. B., Wooden J. L., Cheadle M. J., John B. E., “Fingerprinting” tectono-magmatic provenance using trace elements in igneous zircon. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 170, 46 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Claiborne L. L., et al., “Zircon as magma monitor: Robust, temperature-dependent partition coefficients from glass and Zircon surface and Rim measurements from natural systems” in Microstructural Geochronology: Planetary Records Down to Atom Scale, D. E. Moser, F. Corfu, J. R. Darling, S. M. Reddy, K. Tait, Eds. (John Wiley & Sons, 2018), pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barth A. P., Wooden J. L., Coupled elemental and isotopic analyses of polygenetic zircons from granitic rocks by ion microprobe, with implications for melt evolution and the sources of granitic magmas. Chem. Geol. 277, 149–159 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samperton K. M., et al., Magma emplacement, differentiation and cooling in the middle crust: Integrated zircon geochronological-geochemical constraints from the Bergell Intrusion, Central Alps. Chem. Geol. 417, 322–340 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barth A. P., Wooden J. L., Jacobson C. E., Economos R. C., Detrital zircon as a proxy for tracking the magmatic arc system: The California arc example. Geology 41, 223–226 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKenzie N. R., Smye A. J., Hegde V. S., Stockli D. F., Continental growth histories revealed by detrital zircon trace elements: A case study from India. Geology 46, 275–278 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoskin P. W. O., Black L. P., Metamorphic zircon formation by solid-state recrystallization of protolith igneous zircon. J. Metamorph. Geol. 18, 423–439 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoskin P. W. O., Schaltegger U., The composition of zircon and igneous and metamorphic petrogenesis. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 53, 27–62(2003). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferry J. M., Watson E. B., New thermodynamic models and revised calibrations for the Ti-in-zircon and Zr-in-rutile thermometers. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 154, 429–437 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson E. B., Harrison T. M., Zircon thermometer reveals minimum melting conditions on earliest earth. Science 308, 841–844 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison T. M., Watson E. B., Aikman A. B., Temperature spectra of zircon crystallization in plutonic rocks. Geology 35, 635–638 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barker S. J., et al., Post-supereruption magmatic reconstruction of Taupo volcano (New Zealand), as reflected in zircon ages and trace elements. J. Petrol. 55, 1511–1533 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper G. F., Wilson C. J. N., Charlier B. L. A., Wooden J. L., Ireland T. R., Temporal evolution and compositional signatures of two supervolcanic systems recorded in zircons from Mangakino volcanic centre, New Zealand. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 167, 1018 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carley T. L., et al., Iceland is not a magmatic analog for the Hadean: Evidence from the zircon record. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 405, 85–97 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carley T., Bell E. A., Miller C. F., Claiborne L. L., Harrison M., Striking similarities and subtle differences across the Hadean-Archean boundary: Model melt insight into the early Earth using New Zircon/Melt Kds. Am. Geophys. Union Fall Meet. 2018, V34C-03 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moyen J. F., The composite Archaean grey gneisses: Petrological significance, and evidence for a non-unique tectonic setting for Archaean crustal growth. Lithos 123, 21–36 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nair R., Chacko T., Role of oceanic plateaus in the initiation of subduction and origin of continental crust. Geology 36, 583–586 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moyen J. F., Martin H., Forty years of TTG research. Lithos 148, 312–336 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun I., Raith M., Ravindra Kumar G. R., Dehydration-melting phenomena in leptynitic gneisses and the generation of leucogranites: A case study from the Kerala Khondalite belt, Southern India. J. Petrol. 37, 1285–1305 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu B., et al., Ti-in-zircon thermometry: Applications and limitations. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 156, 197–215 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reimink J. R., Davies J. H. F. L., Bauer A. M., Chacko T., A comparison between zircons from the Acasta gneiss complex and the Jack Hills region. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 531, 115975 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bell E. A., Boehnke P., Harrison T. M., Recovering the primary geochemistry of Jack Hills zircons through quantitative estimates of chemical alteration. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 191, 187–202 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peck W. H., Valley J. W., Wilde S. A., Graham C. M., Oxygen isotope ratios and rare earth elements in 3.3 to 4.4 Ga zircons: Ion microprobe evidence for high δ18O continental crust and oceans in the early Archean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 4215–4229 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maas R., Kinny P. D., Williams I. S., Froude D. O., Compston W., The Earth’s oldest known crust: A geochronological and geochemical study of 3900-4200 Ma old detrital zircons from Mt. Narryer and Jack Hills, Western Australia. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 1281–1300 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cavosie A. J., Valley J. W., Wilde S. A., Correlated microanalysis of zircon: Trace element, δ18O, and U-Th-Pb isotopic constraints on the igneous origin of complex >3900 Ma detrital grains. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 5601–5616 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cavosie A. J., Valley J. W., Wilde S. A., Magmatic δ18O in 4400-3900 Ma detrital zircons: A record of the alteration and recycling of crust in the early Archean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 235, 663–681 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trail D., et al., Constraints on Hadean zircon protoliths from oxygen isotopes, Ti-thermometry, and rare Earth elements. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 8, 6 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilde S. A., Valley J. W., Peck W. H., Graham C. M., Evidence from detrital zircons for the existence of continental crust and oceans on the Earth 4.4 Gyr ago. Nature 409, 175–178 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valley J. W., Peck W. H., King E. M., Wilde S. A., A cool early Earth. Geology 30, 351–354 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wyche S., Nelson D. R., Riganti A., 4350-3130 Ma detrital zircons in the Southern cross granite-greenstone Terrane, Western Australia: Implications for the early evolution of the Yilgarn Craton. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 51, 31–45 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wyche S., Lu Y., Wingate M. T. D., “Evidence of hadean to paleoarchean crust in the Youanmi and South West Terranes, and Eastern goldfields superterrane of the Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia” in Earth’s Oldest Rocks, V. Kranendonk, J. Martin, V. Bennett, E. Hoffmann, Eds. (Elsevier, 2018), pp. 279–289. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wyche S., Evidence of Pre-3100 Ma crust in the Youanmi and South West Terranes, and Eastern goldfields superterrane, of the Yilgarn Craton. Dev. Precambrian Geol. 15, 113–123(2007). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cawood P. A., Hawkesworth C. J., Dhuime B., The continental record and the generation of continental crust. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 125, 14–32 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lowe D. R., Byerly G. R., Geologic evolution of the Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa. Spec. Pap. Geol. Soc. Am. 329, 10.1130/SPE329 (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Byerly B. L., Lowe D. R., Byerly G. R., “Exotic heavy mineral assemblage from a large archean impact.” in 48th Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. held 20-24 March 2017, Woodlands, Texas. LPI Contrib. No. 1964, id.1582 48 (Woodlands, TX, 2017), vol. 48. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Armstrong R. L., Radiogenic Isotopes: The Case for Crustal Recycling on a Near-Steady-State No-Continental-Growth Earth. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. A, Math. Phys. Sci. 10.1098/rsta.1981.0122 (1981). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harrison T. M., Bell E. A., Boehnke P., Hadean zircon petrochronology. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 83, 329–363 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keller C. B., Boehnke P., Schoene B., Temporal variation in relative zircon abundance throughout Earth history. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 3, 10.7185/geochemlet.1721 179–189 (2017). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keller C. B., Schoene B., Statistical geochemistry reveals disruption in secular lithospheric evolution about 2.5 Gyr ago. Nature 485, 490–493 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor S. R., McLennan S. M., The Continental Crust: Its Composition and Evolution. An Examination of the Geochemical Record Preserved in Sedimentary Rocks (Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1985). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bell E. A., Boehnke P., Hopkins-Wielicki M. D., Harrison T. M., Distinguishing primary and secondary inclusion assemblages in Jack Hills zircons. Lithos 234–235, 15–26 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rasmussen B., Fletcher I. R., Muhling J. R., Gregory C. J., Wilde S. A., Metamorphic replacement of mineral inclusions in detrital zircon from Jack Hills, Australia: Implications for the hadean earth. Geology 39, 1143–1146 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herzberg C., et al., Temperatures in ambient mantle and plumes: Constraints from basalts, picrites, and komatiites. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 8, Q02006 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iizuka T., et al., 4.2 Ga zircon xenocryst in an Acasta gneiss from northwestern Canada: Evidence for early continental crust. Geology 34, 245–248 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nelson D. R., Robinson B. W., Myers J. S., Complex geological histories extending for ≥ 4.0 Ga deciphered from xenocryst zircon microstructures. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 181, 89–102 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Diwu C., et al., New evidence for ∼4.45Ga terrestrial crust from zircon xenocrysts in Ordovician ignimbrite in the North Qinling Orogenic Belt, China. Gondwana Res. 23, 1484–1490 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paquette J. L., et al., The geological roots of South America: 4.1Ga and 3.7Ga zircon crystals discovered in N.E. Brazil and N.W. Argentina. Precambrian Res. 271, 49–55 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gehrels G. E., Valencia V. A., Ruiz J., Enhanced precision, accuracy, efficiency, and spatial resolution of U-Pb ages by laser ablation-multicollector-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, Q03017.(2008). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gehrels G., Pecha M., Detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology and Hf isotope geochemistry of Paleozoic and Triassic passive margin strata of western North America. Geosphere 10, 49–65 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Premo W. R., Castiñeiras P., Wooden J. L., SHRIMP-RG U-Pb isotopic systematics of zircon from the Angel Lake orthogneiss, East humboldt range, Nevada: Is this really Archean crust? REPLY. Geosphere 6, 966–972 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ludwig K. R., User’s manual for Isoplot/Ex version 3.00, a geochronological toolkit for Microsoft Excel. Berkeley Geochronology Center Special Publications 14, 1–71 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coble M. A., et al., Trace element characterisation of MAD-559 zircon reference material for ion microprobe analysis. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 42, 481–497 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wiedenbeck M., et al., Further characterisation of the 91500 zircon crystal. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 28, 9–39 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harrison T. M., Schmitt A. K., High sensitivity mapping of Ti distributions in Hadean zircons. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 261, 9–19 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wackernagel H., Multivariate Geostatistics: An Introduction with Applications (Springer, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ghiorso M. S., Hirschmann M. M., Reiners P. W., Kress V. C., The pMELTS: A revision of MELTS for improved calculation of phase relations and major element partitioning related to partial melting of the mantle to 3 GPa. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 3, 1–35 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith P. M., Asimow P. D., Adiabat-1ph: A new public front-end to the MELTS, pMELTS, and pHMELTS models. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 6, Q02004 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boehnke P., Watson E. B., Trail D., Harrison T. M., Schmitt A. K., Zircon saturation re-revisited. Chem. Geol. 351, 324–334 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kleinhanns I. C., Kramers J. D., Kamber B. S., Importance of water for Archaean granitoid petrology: A comparative study of TTG and potassic granitoids from Barberton mountain land, South Africa. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 145, 377–389 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kohler E. A., Anhaeusser C. R., Geology and geodynamic setting of Archaean silicic metavolcaniclastic rocks of the Bien venue formation, fig tree group, northeast Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa. Precambrian Res. 116, 199–235 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Drabon N., Galić A., Mason P. R. D., Lowe D. R., Provenance and tectonic implications of the 3.28–3.23 Ga Fig Tree Group, central Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa. Precambrian Res. 325, 1–19 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang Q., Wilde S. A., New constraints on the hadean to proterozoic history of the Jack Hills belt, Western Australia. Gondwana Res. 55, 74–91 (2018). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.